Library of Congress's Blog, page 153

November 7, 2014

LC in the News: October 2014 Edition

Just as the Washington Nationals were closing out a winning baseball season, the Library of Congress discovered rare footage of the Washington Senators’ 1924 World Series victory over the New York Giants.

“Finding footage that has probably not been seen since its last theatrical run 90 years ago is usually a moment for celebration for fans and archivists,” wrote New York Times reporter Richard Sandomir. “For followers of baseball in Washington, the 1924 World Series victory was the only one for the franchise until it moved to Minnesota as the Twins and won championships in 1987 and 1991.”

“When archivists from the Library’s Packard Campus for Audio Visual Conservation watched the reel, they found nearly four minutes of footage from that 1924 World Series, footage that somehow had remained in nearly perfect condition for 90 years,” wrote Washington Post reporter Dan Steinberg. “Bucky Harris hitting a home run, Walter Johnson pitching four innings of scoreless relief, Muddy Ruel scoring the winning run, fans storming Griffith Stadium’s field: It was all there, and it was all glorious.”

In other news, the Library launched an initiative to celebrate another pastime, as it were: Halloween. The American Folklife Center has been gathering photographs of people participating in the traditions and celebrations at the end of October and beginning of November in an effort to create an archival photo collection of this slice of folklife.

“This is a good chance to show off your photography skills and maybe be a part of the annals of history,” wrote Tanya Pai for the Washingtonian.

Promoting the initiative were other outlets including McClatchy News Service, School Library Journal and Boing Boing.

Speaking of photographs, Mashable ran a fascinating pictorial piece on photographs by a young Stanley Kubrick while working for Look Magazine. The Library is home to the magazine’s archives.

2014 marked the 100th anniversary of the opening of the Panama Canal. The Library has a variety of resources related to the historic waterway and pulled items from the collections for a special exhibit. C-Span’s American Artifacts series presented a feature on the canal and the Library’s collections.

C-SPAN also covered a Library symposium that was part of the ongoing commemoration of the Civil Rights Act. Former member of the Black Panther Party, Bill Jennings, joined author Lauren Araiza to discuss multiracial coalitions during the civil rights movements of the 1960s and 70s.

In addition, Christian Science Monitor chose the Library’s exhibition “The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom” as a “top pick” in the arts for October saying “Smartly written, it highlights images, letters, and audio components from the library’s collection to illustrate the fight to establish social and racial equality.”

The Library of Congress continues to be recognized for its innovation and commitment to advancing human knowledge, creativity and understanding. The Good Magazine’s Cities Project recently named the institution a “Hub for Progress” noting that the Library and other locations have “emerged as particularly kind to collaboration and innovation, ushering along vital advances for human progress in a diverse range of fields.”

The Fall/Winter 2014 issue of Geico NOW magazine called the Library a “world leader” and “Library of dreams.”

Celebrating Native American Heritage: Whispering Giants

Statue of the Cherokee leader Sequoyah, Cherokee, N.C. Photograph by Carol M. Highsmith, between 1980 and 2006. Print and Photographs Division.

November is Native American Heritage Month and a time to celebrate rich and diverse cultures, traditions and histories and to acknowledge the important contributions of Native people. When looking through the Library’s collections to find blog post ideas, I came across this picture of a carved statue of Cherokee leader Sequoyah taken by photographer Carol M. Highsmith. It actually reminded me of a similar piece of art found in my hometown of Ocean Springs, Miss. – that of another large carved sculpture of a Native American. The statue, known as Crooked Feather, sits overlooking Highway 90, just east of the Biloxi Bridge. The local landmark has been there for as long as I can remember, and I’ve always wondered the story behind it.

Prior to its colonization in 1699, the area along the Gulf Coast was inhabited by American Indian tribes including the Bylocchy, Pascoboula and Moctoby. Crooked Feather is a composite of the area’s first settlers. The 30-foot sculpture is carved from a cypress log five-feet wide by 11-feet high. The original Crooked Feather was created in 1975 by Hungarian artist Peter Wolf Toth and officially donated to the city a year later. However, due to termite damage, Toth’s work was replaced in 1999 by a replica carving done by Thomas King.

Crooked Feather was part of Toth’s sculpture series called “Trail of the Whispering Giants” paying tribute to the tribal people of the country. Some 74 sculptures, including at least one in every state, as well as parts of Canada and Hungary, are part of the collection. Turns out, the Highsmith photograph of Sequoyah is also one of Toth’s creations that can be found in Cherokee, N.C.

Peter Toth sculpting Crooked Feather in 1975 and the completed memorial photographed in March 1997. Photo courtesy of Ocean Springs Archives.

The Library is marking Native American Heritage Month with a topic page in partnership with other federal agencies like the Smithsonian Institution, the National Archives and the National Portrait Gallery. The site includes online resources related to Native American history. In addition, the Library has launched a Pinterest board dedicated to Native American Heritage Month, featuring images from the Library’s collections.

You can read more about Sequoyah in this blog post from the Library’s Inside Adams blog and another post from the Prints and Photographs blog.

The Library’s blogosphere has several other posts highlighting Native American Heritage Month and related collections and resources. Make sure to check back for new posts. In the meantime, here are some great posts relating to Native American music, legislation and teacher resources.

November 6, 2014

Pic of the Week: Dr. Funkenstein

George Clinton performs at the Library of Congress on Oct. 31. Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

In 1994, I had the pleasure of meeting funk singer-songwriter George Clinton while attending the Lollapalooza music festival in New Orleans. Clinton and his P-Funk All Stars were main-stage performers that year. A friend of mine and myself were able to get backstage after meeting one of the members of his band. Clinton and his crew were getting ready in their trailer, and I had a chance to chat with the Rock and Roll Hall of Famer for a very brief moment. Following, we enjoyed a front-and-center view of his performance, which was fantastic.

Twenty years later, things came full circle of sorts when Clinton was here at the Library last Friday. To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act, he was here promoting his book, “Brothers Be, Yo Like George, Ain’t That Funkin’ Kinda Hard on You?” and speaking about his decades-long musical career.

“Funkin’ ain’t hard at all,” said the 73-year-old funk pioneer as he took the Coolidge Auditorium stage to be interviewed by James Funk of WPFW.

The two bantered back and forth for the next 20 minutes, discussing just about everything, including Clinton’s early days with The Parliaments in the 1960s, developing his musical collective during the 70s known both as Parliament and Funkadelic, his efforts to win back rights to much of his popular music and the indelible mark his music has made on contemporary artists of today.

“We were too late getting to Motown, and we didn’t fit into that mold,” said Clinton. “We went psychedelic ‘loud Motown.’ We made our own niche and then didn’t have to compete.”

Clinton said his fan base grew slowly but steadily. When his 1975 album “Mothership Connection” came out, it “blew the whole thing wide open.” It became Parliament’s first album to be certified gold and later platinum. The Library also added the album to the National Recording Registry in 2011 for its “enormous influence on jazz, rock and dance music.”

“I’ve enjoyed all the time it took to get where I’m at,” he said of his career’s successes and setbacks.

While Clinton didn’t bring the weird on the Halloween afternoon – gone were the multi-colored dreadlocks and flashy clothes that I remembered, along with is costume-clad band – he did bring the funk, rousing the crowd with a musical medley of some of his greatest hits. And, he was just as entertaining.

November 5, 2014

Royalty, Justices Help To Celebrate Magna Carta

(The following is an article written by Mark Hartsell for The Gazette, the Library of Congress staff newsletter.)

The Library of Congress will celebrate the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta and the opening of its new exhibition about the historic charter with programs, both public and private, featuring three U.S. Supreme Court justices and a royal touch.

The Library of Congress will celebrate the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta and the opening of its new exhibition about the historic charter with programs, both public and private, featuring three U.S. Supreme Court justices and a royal touch.

Beginning this week, Princess Anne, U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Associate Justice Stephen G. Breyer and Associate Justice Antonin G. Scalia will take part in discussions that explore the enduring influence of Magna Carta, the charter at the heart of English and American law.

“The events related to the Library’s celebration of Magna Carta’s 800th anniversary are designed to welcome visitors to the Library to learn more about the Great Charter’s impact on the rule of law,” Law Librarian David Mao said. “The Law Library developed programming that not only celebrates the document but also raises awareness and invites discourse about its history, impact and relevance to today’s legal issues.”

The 10-week exhibition, “Magna Carta: Muse and Mentor,” opens tomorrow in the Jefferson Building’s South Gallery and closes Jan. 19. The show’s centerpiece is the Lincoln Magna Carta – one of only four remaining original documents to which King John affixed his seal at Runnymede in 1215.

That copy of Magna Carta – on loan from Lincoln Cathedral in Britain – will be accompanied by more than 75 items from Library collections that tell the story of the charter’s influence on centuries of political liberty.

Exhibition-related events begin this afternoon, when Roberts and the former chief justice of England and Wales, Lord Igor Judge, discuss the importance of Magna Carta in a conversation in the Jefferson Building’s Members Room. That event is closed to the public. However, a video of the discussion will be posted on the Library’s website.

The exhibition opens the next morning with an “entrusting ceremony” in the Great Hall, in which Magna Carta is formally placed on loan to the Library. Princess Anne, the daughter of Queen Elizabeth, will address the audience, as will Librarian of Congress James H. Billington; Mao; and Lord Lothian, cousin of the British ambassador to the United States who in 1939 delivered Magna Carta to the Library for safekeeping during World War II. Sir Peter Westmacott, the current British ambassador to the United States, also will take part in the ceremony.

Music will be provided by the U.S. Army Herald Trumpets, the choir of the Temple Church in London and the Howard University choir. The event, which begins at 10:15 a.m., is open to the public. Space will be limited.

On Dec. 9, philanthropist David Rubenstein will interview Breyer in the Coolidge about the impact of Magna Carta on American law as part of a day long symposium, “Conversations on the Enduring Legacy of the Great Charter.”

The symposium’s morning sessions, in the Members Room, are closed to the public. The six afternoon sessions in the Coolidge – including the appearance by Breyer – are open to the public. Details about the afternoon sessions will be posted later in November.

The series also includes gallery talks in November and a Law Day event in the spring. On Nov. 12, exhibition curator Nathan Dorn of the Law Library will discuss highlights from the exhibition. On Nov. 19, Susan Reyburn of the Publishing Office will discuss “Magna Carta in America: From World’s Fair to World War,” including the charter’s first visit to the Library of Congress in 1939.

Finally, the Law Library on April 7 will stage a Law Day program featuring Nicholas Vincent, a professor of medieval history at the University of East Anglia in Britain. Vincent will present “Magna Carta: New Discoveries.”

King John affixed his seal to Magna Carta in a grassy meadow at Runnymede in June 1215, when rebellious barons coerced him into granting certain rights and liberties. Scribes made parchment copies and sent them to bishops, sheriffs and other officials across England. Of the four surviving original copies, the Lincoln Magna Carta is considered the best-preserved and easiest to read. It also has the clearest provenance: On the back, scribes wrote “Lincolnia” – the Latin form of its intended destination.

The charter arrived at Lincoln Cathedral about June 30, 1215, and has been held by the cathedral ever since. Magna Carta today is considered a historic symbol of the rule of law: No one – even a king – is above the law.

Magna Carta established some principles – trial by jury and no taxation without representation, among them – that resonated around the world and down through the ages, including with the framers of the U.S. Constitution.

“The events of 800 years ago marked the commencement of a major undertak ing in human history,” Roberts said at the American Bar Association annual meeting in August. “We mark the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta because it laid the foundation for the ascent of liberty. We celebrate not so much what happened eight centuries ago as what has transpired since that time.”

The Library’s exhibition is made possible by The Federalist Society and 1st Financial Bank USA. Additional support comes from the Friends of the Law Library of Congress, BP America, The Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, the Earhart Foundation, White & Case LLP, The Burton Foundation for Legal Achievement, the Office of the General Counsel of the American University, and other donors as well as contributions received from Thomson Reuters, William S. Hein & Co. Inc., and Raytheon Company through the Friends of the Law Library. The Library also acknowledges the support and assistance provided by the British Council. This exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

October 31, 2014

A Spirited Story

A Harris Poll of 2,250 people surveyed in November 2013 found that 42 percent of Americans said they believe in ghosts. And, nearly one-in-five adults in the United States say they have seen or been in the presence of a ghost, according to a 2009 Pew Research Center survey.

[image error]

Double exposure “spirit” photograph of girl standing, holding flowers, surrounded by spectral figures of three people. Photograph by G.S. Smallwood, Chicago, Ill., c1905. Prints and Photographs Division.

Many people know of at least one ghost story that has been told within their family – my dad likes to say it’s his Uncle George watching over us when something strange happens around us, particularly in their house.

And some even believe they know of haunted houses close to where they lived.

I can recall a night spent at The Myrtles Plantation, an antebellum home in St. Francisville, La., that’s been the subject of several paranormal television shows and often known as one of America’s most haunted homes. Me and a friend of mine had the place all to ourselves, which certainly upped the creepy factor. While I can’t say that we saw any unexplained phenomena, each bump and creak of the house throughout the night could certainly have been any number of haunted happenings. We believed.

Our folklore is rich with tales of haunted happenings.

Eldora Scott Maples tells the tale of the family ghost, Alex – short for Alexander the Great – who came to her father when he was 12 and kept watch over him and the family through the years.

“When my father was 12 years of age he heard a strange tap, tap one night as he lay in bed that sounded as if water was dripping from the top of the house down to a feather mattress. The tap, tap came repeatedly through a duration of a year or more before he recognized that some message was trying to be revealed. The tap, tap, tap, appeared so frequently that they soon ceased to be taps but were an insistent stream, then stopped when the usual tap, tap, tap, began as before. While in that lone room in the stillness of the night with blared eyes the constant tap, tap, never varying from sound except by frequency, my father decided that the visitor was a ghost.”

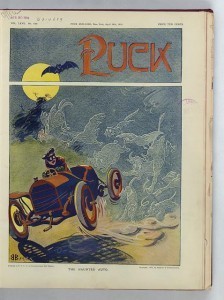

The haunted auto by artist Bryant Baker. April 20, 1910. Prints and Photographs Division.

Her story is just one of many in American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1940. The Library’s collections hold other ghostly tales sure to fright and delight, including a story about phantom horses heard in Rock Creek, W.V.

If seeing is believing, you can also search the Library’s online motion picture collections for movies on ghosts. See, for example, “Uncle Josh in a Spooky Hotel” from the collection Inventing Entertainment: The Motion Pictures and Sound Recordings of the Edison Companies and “Dud Leaves Home“ from Origins of American Animation.

October 29, 2014

Pic of the Week: A Tree for CRS

CRS Director Mary B. Mazanec, Librarian of Congress James H. Billington (from left), Architect of the Capitol Stephen Ayers and Rep. Jim Moran shovel dirt around a newly planted commemorative tree on Monday. Photo by David Rice.

The Congressional Research Service celebrates its centennial this year. To mark the occasion, a commemorative tree was planted on the grounds of the Thomas Jefferson Building. The 10-foot Japanese maple serves as a living memorial to the men and women who have served in the legislative branch agency within the Library of Congress.

A plaque at the base of the tree notes the species, date and occasion: “Sponsored by James H. Billington, the Librarian of Congress, in honor of Congressional Research Service’s Centennial.”

The service officially was born July 18, 1914, when then-Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam, following a congressional directive, issued an administrative order establishing a legislative-reference unit at the Library. In 1970, the Legislative Reorganization Act gave the agency an expanded mission and a new name – the Congressional Research Service.

October 27, 2014

Astrobiology Chair Steven Dick Discusses Research, Tenure at the Library

(The following is a repost from the Insights: Scholarly Work at the John W. Kluge Center blog. Jason Steinhauer spoke with Steven Dick, Baruch S. Blumberg NASA/Library of Congress Chair in Astrobiology, who concludes his tenure at the Kluge Center this month.)

How the Discovery of Life Will Transform Our Thinking

October 27, 2014 by Jason Steinhauer

Astrobiology Chair Steven Dick believes that the discovery of life in the universe is a question of when, not if. Such a discovery will take different forms: microbial life, possibly complex life, maybe even intelligent life. Researching the scenarios and investigating the potential outcomes and ramifications has been at the essence of Dick’s year-long residency at the Kluge Center. He sat down with Program Specialist Jason Steinhauer to talk about the nature of discovery, the societal and policy ramifications of discovery, and how he used the Library of Congress collections in his research.

Good morning, Steven, and thanks for being here. Let’s start with this: your tenure as Astrobiology Chair at the Kluge Center is drawing to a close, concluding on November 1. Any thoughts or reflections as your time winds down?

It’s been a fabulous year, beginning with testifying at a Congressional hearing on astrobiology in December, then the astrobiology and theology conversation in June, and finally the big astrobiology symposium in September, “Preparing for Discovery.” While here I’ve worked on both the proceedings of our astrobiology symposium, which will be published as a trade volume by Cambridge University Press, and I’ve finished most of the research for my upcoming book, tentatively titled “Cosmic Encounters: How the Discovery of Life Will Transform Our Thinking.” That’ll also be the subject of my final lecture. It’s been everything I thought it would be and more.

Let’s pick up on the topic of your final lecture: How will the discovery of life beyond Earth transform our thinking?

Well, you always have to set out the scenarios: if it’s microbes that’s one thing, if it’s intelligence that’s another thing. But even if we find single-cell organisms, it has the potential to transform our scientific knowledge. The quest for a universal biology has been one of the big inquiries of science, but it’s hard to have a universal biology or a definition of life when you only have one example-life on Earth. Life on Earth is all carbon-based, relies on DNA as its genetic code, and has water as a solvent. Out in the Solar System and beyond it could be quite different. If we discover a different form of biochemistry or a different kind of genetic code-or a different kind of solvent such as a hydrocarbon as opposed to water-that would be exciting. We’d then have an opportunity to come up with some general rules of biology and a universal biology might be attainable.

So the discovery of something as tiny as a microbe could have a seismic effect.

When we thought we found fossils in a Mars rock in 1996, it had huge effect. So imagine the discovery of living bacteria. When we thought we’d found fossils in 1996, President Clinton expressed interest, there was a symposium convened by Vice President Gore on the subject, and there were Congressional hearings, not to mention the debate in the scientific journals. That’s likely to be what happens when we have a real discovery. As part of my research this past year I’ve looked into the nature of discovery. Discovery is an extended process, which consists of detection, interpretation, and understanding. If and when we discover life beyond Earth, it’s going to be an extended process. By studying the history of past discoveries, we can gain insights into how future discoveries may unfold. It’s the same pattern each time: detection, followed by a long period of interpretation until, ultimately, we understand what it is. It’ll take a period of years to know what we really found.

Would the change in our thinking unfold over a similar extended period?

Absolutely. The impact will take place over a long period of time. I’ve used the analogy of culture contacts, wonderfully documented in the Kislak Collection of the Cultures and History of the Americas here at the Library of Congress, to help in this regard. It’s not a direct analogy, of course, but there are lots of interesting insights uncovered when you examine what Europeans thought the Native Americans would be like, and vice versa. There are subtle lessons: problems in communication, how different brains or minds perceive experiences based on strongly-held cultural beliefs and norms. This analogy more pertains to the potential discovery of intelligent life. I believe we’re much too sanguine about our ability to communicate with any potential intelligent life beyond Earth. But it’s an interesting problem to attempt to transcend anthropocentrism and think more broadly about what might be the landscape of life in the universe. I believe that any discovery we make will be quite surprising.

§ Watch: Steven Dick on doing research in the Library of Congress. Filmed by Feature Story News.

Suppose we discover bacteria at the bottom of a lake on Titan. How do we fit that into our understanding of evolution and natural selection? How do we integrate cosmic evolution into our scientific way of thinking?

Everything in the universe is evolving, and has been since the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago. Biological evolution is one local example of cosmic evolution. We know the universe is evolving physically; we know species evolve biologically; and we know cultures evolve. If the universe is biological and cultures evolve, then you get into the concept of post-biologicals. Maybe biological life is just a passing phase in the universe, and what we’re looking for out there is quite different from biological life? But to your question, I see no reason why evolution by natural selection would not be true elsewhere in the universe. If we found bacteria in a hydrocarbon lake on Titan, a moon of Saturn, I believe it would have evolved under natural selection, which means it will have evolved under the conditions of its natural habitat. We’re searching for a universal biology and we’re looking for principles, and I believe the number one universal biological principle throughout the universe would be natural selection.

And in this hypothetical scenario, if we find microbes on Titan we’d then want to ask what came before it and what comes after it.

Right. We examine how species evolve here on Earth, and that’s what we’d do on another planet. We’d attempt to fit into an evolutionary scheme. That would be a good problem to have!

What are the politics of extraterrestrial life, from your vantage point?

This is more than an academic problem. It has political and societal implications. In both Congressional hearings on astrobiology, Members of Congress asked what do we do if we discover something? There’s been some work on this problem, but not enough, in my opinion. There are some basic planetary protection protocols regarding the microbial situation, but they haven’t gone much beyond that. And there are no protocols for intelligent life beyond “confirm first and then tell everyone.” This is not for a single person to figure out. It would need to be an interdisciplinary group that includes elected officials, scientists, humanists, and theologians. The theological implications would play out for each religion over the course of time. By the way, it seems largely to be western culture that has the preoccupation with life beyond Earth. It’s an interesting question why that is. Eastern cultures do not seem as preoccupied, whereas western scientists and popular culture are consumed by it. Why that is is an interesting research question that I’ve not explored.

How have the Library’s collections aided you while here?

Well, I’ve already spoken about the Kislak Collection. That collection helped lay out the guidelines for the questions we might ask ourselves as we devise these contact and discovery scenarios. They are questions, as opposed to answers, but they are the start of preliminary reconnaissance on this topic. While here I looked at hundreds of books in the Library’s collections, in areas of cultural contact, cognitive science, philosophy and the question of objective knowledge. I’m not an expert in all these areas, but my book will be very broad covering science, history, theology and anthropology. My hope is that the experts will contribute more to this discussion. And of course the Kluge Center makes the access to these wonderful collections possible.

Any final thoughts you wish to add?

Only that I highly recommend the Kluge Center to everybody, and encourage any scholar to apply for the fellowships offered. I’ll add that I’ve also been pleasantly surprised to learn what a vibrant place the Library of Congress is. There are always things going on here, with free talks, concerts, and events happening daily. It’s an intellectually vibrant place and I’ve really enjoyed it.

Steven Dick delivers his final lecture as Astrobiology Chair, “How the Discovery of Life Will Transform Our Thinking,” on Thursday, October 30th at 4 p.m. at The John W. Kluge Center, room LJ-119 of the Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building. The event is free and open to the public.

October 24, 2014

Pianist, NLS Making Beautiful Music Together

Jazz pianist Justin Kauflin is quick to laugh and down to earth, taking his national success in stride, especially for a 28-year-old musician. Kauflin has a CD of his original music coming out in January, is currently promoting a documentary film about his friendship with noted jazz trumpeter Clark Terry and has toured with the likes of Quincy Jones, who also signed him to his production company.

Jazz pianist Justin Kauflin performed on Wednesday at the Coolidge Auditorium. Photo by Mark Layman.

While Kauflin’s accomplishments are noteworthy, his rise to acclaim hasn’t been without difficulty. The young musician suffered from low vision his entire childhood and became completely blind by age 11 due to a rare eye disease. Despite these circumstances, he showed musical promise as early as 2 years old, playing the piano as soon as he could reach the keys. He also studied the violin.

“I was interested but not dedicated,” Kauflin admitted of his musical education. Still holding his attention were things like basketball, video games and, in general, being a kid.

Once he completely lost his sight, music and the piano became central to his life. He shifted his focus from classical to jazz when he enrolled in the Governor’s School for the Arts in Norfolk, Va., and began performing jazz professionally at age 15 while still in school.

In 2004, Kauflin graduated as valedictorian at the Governor’s School and received a presidential scholarship at William Paterson University in New Jersey, where he received a degree in music. While at WPU, he counted Terry and the late Mulgrew Miller among his mentors – both would also help him realize a full-time career as a jazz pianist.

“They both taught me that who you are as a person comes out in your music,” Kauflin said.

While Miller passed away last year, Kauflin and Terry’s relationship is stronger than ever. The two are featured in the 2014 documentary, “Keep on Keepin’ On,” which has won multiple film festival awards.

On Wednesday, Kauflin took to the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium stage in a special concert presented by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped (NLS) at the Library of Congress. His was the third concert presented by NLS to highlight the Music Section and its services.

In high school, Kauflin became a patron of NLS. He began borrowing instructional braille music materials but soon moved on to easy and then intermediate piano works in braille by classical composers. By 2007, he had started borrowing more advanced material. Among his favorites then and now are works by Bach and Chopin.

“It’s been a wonderful process,” he said of using NLS. “It enabled me to work on what one should while studying the piano – how to interpret music and make it your own.”

Kauflin is particularly excited about NLS’s Braille and Audio Reading Download (BARD) app.

“It allows me to sync up my iPhone with braille music scores,” he explained. “I’m thrilled at that because it’s another way of getting music.

“The service NLS provides is invaluable. The difference from before I used the service to now is staggering. There is so much more I can consume.”

October 22, 2014

Opera Onstage, Drama Offstage

Today marks the anniversary of the opening of the original Metropolitan Opera House in New York City, on Oct. 22, 1883. This is the hall, no longer in existence, where Enrico Caruso performed “Vesti La Giubba” in “Pagliacci”; where Geraldine Farrar sang “Un Bel Di,” in “Madame Butterfly.” Thanks to radio broadcasts, it was the center of attention for opera-lovers coast to coast on Saturday afternoons from 1931 until the opening of the Met’s current hall in Lincoln Center in September of 1966. The broadcasts continue, and since 2006 people at various movie theaters around the country can also see select Met productions televised live in high definition, for about the price of a standee spot at the live show.

By now we’re used to the storyline (usually comic) in which what’s going on offstage is even more dramatic than what’s happening onstage (Marx Brothers, “A Night at the Opera”) – even though operas have been known to end with heroines flinging themselves off parapets (“Tosca”), the Old Believers immolating themselves (“Khovanshchina”), or the dissolute, unrepentant title character being dragged into Hell (“Don Giovanni”).

Looking up through one of the curving staircases at the Metropolitan Opera. Photo by Adriel Bettelheim

Yet sometimes, the drama-about-the-drama is not a commedia. This season, the Met has had to respond to a controversy over its offering of living American composer John Adams’ 1991 opera “The Death of Klinghoffer,” which, opponents allege, glorifies terrorism and anti-Semitism. Adams, who spoke at the Library in 2010 and had a residency here in 2013, takes his opera storylines from recent history; the Klinghoffer story harks back to an actual incident that took place on a cruise ship boarded by terrorists in 1985. Adams’ other well-known operas are “Nixon in China,” about the former president’s visit to Mao Zedong in 1972, and “Dr. Atomic,” a dramatization of what was going on in the mind of scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer during a critical period in the Manhattan Project to develop the atom bomb.

Only time will tell where “Klinghoffer” will be, in the pantheon of opera, in another 50 years, or 100, or 200. It opened to protests, but also to applause, at the Met on Monday.

Also on the Met’s schedule this year is a production of Mozart’s “The Marriage of Figaro,” an opera based on a story by Beaumarchais banned in many courts during Mozart’s lifetime because it featured a serving-man outwitting his noble overlord.

And the Met, in a few weeks, will open Dmitri Shostakovich’s infrequently seen “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk,” which in 1936 was said to be so despised by Stalin that Shostakovich’s musical career within the U.S.S.R. took a crushing blow, led by an editorial in “Pravda,” that required years to recover from. That opera is almost better known as a censorship target than on its own merits.

The Library of Congress holds one of the world’s foremost collections of opera-related manuscripts, sheet music, photographs and stage designs. In addition to the sampling of these treasures brought forward in last year’s exhibition “A Night at the Opera,” the Library offers many streaming recordings by famous early stars of opera on its National Jukebox website (here’s the Barcarolle from “Tales of Hoffman.“)

And speaking of the Marx Brothers – we’ve got Groucho’s papers, including the script for “A Night At the Opera.” That 1935 classic is also a 1993 entry in the Library’s National Film Registry.

October 16, 2014

A-B-C … Easy as One, Two, Three

Noah Webster, ca. 1867. Prints and Photographs Division.

On Oct. 16, 1758, Noah Webster, the “Father of American Scholarship and Education” was born. Lexicographers everywhere celebrate his contributions on his birthday, also known as “Dictionary Day.”

As a young, rural Connecticut teacher, he used his own money to publish his first speller in 1783. Reissued throughout the 19th century, the 1829 “Blue Back Speller” was second only to the Bible in copies sold. After his death in 1843, the rights to his dictionary were sold to George and Charles Merriam, whose company is now known as Merriam-Webster Inc. The Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division holds a copy of the 1829 edition and Webster’s first speller from 1783.

An active federalist, Webster became a pamphleteer for centralized government and was critical of the politics of self-aggrandizement. Clearly setting himself with the nation’s founders, he believed that if a man was dependent financially on someone, he could not serve the public good but would only be concerned about his dependent relationship. A politician had to be independent – owning his own land and not directly involved in the marketplace. To Webster, George Washington was the epitome of this disinterested leader. You can find several letters written between the two in the online collection of the Library’s collection of the George Washington Papers. His support of the founding fathers led him to maintain correspondence with James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, both of whose papers are also held at the Library.

Noah Webster. Born 1758-died 1843. The schoolmaster of the republic. Print, Dec. 19, 1891. Prints and Photographs Division.

Webster was also an advocate for copyright laws and traveled widely to further legislation, including the Copyright Act of 1831. The Library is the home of the U.S. Copyright Office, where you can find information on how to register a work, learn about copyright law and search copyright records.

Author Jonathan Kendell’s book, “The Forgotten Founding Father: Noah Webster’s Obsession and the Creation of an American Culture” (2011) recounts Webster’s life as a successful publisher, public servant and political confidante. Kendall spoke at the Library following the publishing of his book.

{mediaObjectId:'FD3AA16A0D2C01ECE0438C93F02801EC',playerSize:'smallStandard'}

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers