Library of Congress's Blog, page 150

January 30, 2015

Buying a Library

James Madison, fourth president of the United States. Between 1836 and 1842. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Two hundred years ago today, President James Madison approved an act of Congress appropriating $23,590 for the purchase of a large collection of books belonging to Thomas Jefferson in order to reestablish the Library of Congress.

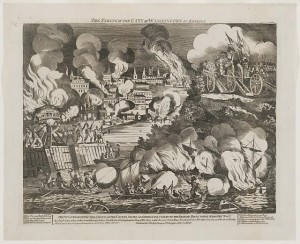

Under Madison’s leadership, the United States went to war with Great Britain in 1812. After capturing Washington, D.C. in 1814, the British burned the U.S. Capitol, destroying the Library of Congress and its 3,000-volume collection. Jefferson offered to sell his personal library to the Library Committee of Congress in order to rebuild the collection of the Congressional Library.

In a letter to his friend Samuel Smith, Jefferson wrote, “I do not know that it contains any branch of science which Congress would wish to exclude from this collection . . . there is in fact no subject to which a member of Congress may not have occasion to refer.”

Jefferson’s collection contained more than twice the number of books Congress lost in the fire and included a much wider range of subjects. The previous library covered only law, economics and history.

The purchase of Jefferson’s library wasn’t without some controversy. According to the Office of the Historian of the U.S. House of Representatives, Congress took more than three months to deliberate.

According to the “Annals of Congress,” “The objections to the purchase were generally its extent, the cost of the purchase, the nature of the selection, embracing too many works in foreign languages, some of too philosophical a character, and some otherwise objectionable. Of the first description, exception was taken to Voltaire’s works, &, co., and of the other to Callender’s ‘Prospect Before Us.'” (pg. 398)

The taking of the city of Washington in America. Published by G. Thompson, Oct. 14, 1814. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

“Those who opposed the bill, did so on account of the scarcity of money and the necessity of appropriating it to purposes more indispensable than the purchase of a library; the probablE insecurity of such a library placed here; the high price to be give for this collection; its miscellaneous and almost exclusively literary (instead of legal and historical) character, &c.

“To those arguments, enforced with zeal and vehemence, the friends of the bill replied with fact, wit, and argument, to show that the purchase, to be made on terms of long credit, could not affect the present resources of the United States; that the price was moderate, the library more valuable from the scarcity of many of its books, and altogether a most admirable substratum for a National Library.” (pg. 1105)

Approved by the Senate on Dec. 3, 1814, the bill passed in the House of U.S. Representatives on Jan. 26, 1815.

Madison’s connection to the Library of Congress actually existed long before 1815. He first proposed the idea of a congressional library in 1783. That year, a committee chaired by Madison submitted a list of approximately 1,300 books to the Confederation Congress that were “proper for the use of Congress.” Madison urged that “it was indispensable that congress should have at all times at command” authorities on public law whose expertise “would render . . . their proceedings conformable to propriety; and it was observed that the want of this information was manifest in several important acts of Congress.” His proposal was defeated because of “the inconveniency of advancing even a few hundred pounds at this crisis.”

However, it was under the authority of President John Adams that the Library of Congress was established through an act of Congress on April 24, 1800.

Madison’s contributions to the establishment of the Library are memorialized in one of the main buildings on the institution’s Capitol Hill campus: not only is the James Madison Memorial Building named after the fourth president but there is also a statue of him inside.

January 28, 2015

The Library to the Rescue

(The following is a story in the January/February 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

Library of Congress restoration specialist William Berwick took this photograph of the New York State Library’s folio edition of John James Audubon’s “Birds of America” in the aftermath of the 1911 fire. Manuscript Division.

The Library of Congress has a long tradition of assisting other institutions in preserving their collections.

Nearly a century after the Library of Congress collection was destroyed by a fire in the U.S. Capitol building in 1814, the New York State Library in Albany, N.Y., experienced a similar fate.

On March 29, 1911, just weeks before the New York State Library was scheduled to move to the newly constructed State Education Building, a fire ravaged the State Capitol, which housed the library. While parts of the building were unaffected, the State Library and its collection of 600,000 volumes were badly damaged. As the New York State National Guard worked to secure the building and safeguard its contents, a member of the staff of the Library of Congress helped to preserve the collections of the State Library.

William Berwick, a bookbinder at the Government Printing Office, had been detailed to the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress in 1899. Berwick quickly established himself as the American master in the Vatican technique of silking, as well as other restoration techniques. The technique–adhering silk gauze to both sides of a deteriorated document–was state-of-the-art at the time. Berwick directed the State Library staff in the restoration of John James Audubon’s priceless “double-elephant” folios of hand-colored plates illustrating more than 700 species of North American birds published between 1826 and 1838.

November 1966 witnessed the flooding of the Arno River in Florence, Italy, which damaged millions of art masterpieces and rare books housed in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze. Library of Congress staff were among the volunteers led by British bookbinder and conservator Peter Waters, who were dispatched to clean, dry and re-bind some of the library’s most valuable volumes. Waters, who had trained at the Royal Academy of Art, was subsequently appointed head of the newly created Restoration Division (today the Conservation Division) at the Library of Congress, and served in that position until his retirement in 1995.

In the five decades following the Florence Floods, the Library’s trained staff has continued to assist in the aftermath of natural and man-made disasters at home and abroad. For example, Library conservators were dispatched to the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg following a devastating fire in 1988. In 2003, they helped reconstruct the National Library of Iraq, which was destroyed under Saddam Hussein’s regime, and they advised on the establishment of a memorial archive following the 2007 shooting at Virginia Tech. Most recently, Library staff helped with disaster-recovery efforts following the earthquake in Japan and the fire at the Institut d’Egypte in Cairo. Library conservators have provided training to personnel in the national libraries, museums and archives of more than a dozen countries throughout the world

Library of Congress Archivist Cheryl Fox and Paper Conservation Section Head Holly Krueger contributed to this article.

January 23, 2015

Conservator’s Picks: Treating Treasures

(The following is a story in the January/February 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

Conservation Division chief Elmer Eusman discusses conservation treatment options for a variety of prized collection items.

“Collections such as this classic Maya whistling vessel, dated A.D 400-600, are safeguarded in customized storage boxes constructed of smooth, inert materials that provide padding without abrading the surface of the object. The boxes are designed with drop walls or easily removable padding to provide safe access to the collection of fragile and irreplaceable objects.” Jay I. Kislak Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division

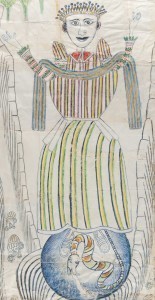

“This 1951 drawing is one of the earliest surviving works by the self-taught, “outsider” artist. His ‘Madonna’ was drawn on the back of 22 pieces of postal mail, patched together using pastes he made by chewing starchy foods such as bread, oatmeal and potatoes–items found at the hospital where he was treated for schizophrenia.

Library conservators flattened the many creases, mended the tears and filled the losses.” Charles and Ray Eames Collection, Prints and Photographs Division

Map of Cape Breton, Nova Scotia

Map of Cape Breton, Nova Scotia

“Hand drawn by Lamiralle Boucoune, this map depicting a pivotal battle at Cape Breton during the French and Indian War was discolored and illegible.

Conservators removed the brown-colored silk fabric that had been pasted onto the surface, washed the item to remove discoloration and mended the many tears and losses.

After treatment, many details and colors were once again visible.” Geography and Map Division

“Originally housed in a separate, telescoping carrying pouch, this traditional Ethiopian text written on vellum (‘Prayer to Our Lady the Virgin, Mother of Light’) is now housed in a custom-fitted box. The boards are wood, covered in leather. This rare item bears the hallmarks of a traditionally bound Ethiopian manuscript.” Thomas L. Kane Collection, African and Middle Eastern Division

This platinum photograph by Zaida Ben-Yusuf (1869-1933) is an excellent example of pictorialist photography– a style in which the photographer manipulates the image rather than simply recording it. The Library’s photograph conservators are conducting research into how platinum photographs were made, how they deteriorate and what treatments are possible to preserve them for future generations. Frances Benjamin Johnston Collection, Prints and Photographs Division

January 21, 2015

American Ballet Theatre Exhibit Closes Saturday

The Library of Congress exhibition, “American Ballet Theatre: Touring the Globe for 75 Years,” closes this Saturday, so if you’re in town, make sure to visit.

American Ballet Theatre (ABT), which celebrated its 75th anniversary in 2014, donated its archives of more than 50,000 items of visual and written documentation to the Library. The exhibition features a selection from the collection, including photographs, scores, costume sketches, posters and programs.

The ABT materials enhance and complement the Library’s many other dance, theater and music collections held in its Music Division, including the papers of composers Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland and Morton Gould, set designer Oliver Smith and choreographer Bronislava Nijinska.

The exhibition is on view from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. in the Performing Arts Reading Room, located on the first floor of the James Madison Memorial Building, 101 Independence Ave., S.E., Washington, D.C.

January 16, 2015

The Science of Preservation

(The following is a story written by Jennifer Gavin for the January/February 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

Preservation specialist Michele Youket assesses CD damage through a microscope known as an Axio Imager. Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

Scientific research in its laboratories helps the Library to preserve and display world treasures.

Books with cracked leather bindings; crumbling, yellowed maps and newspapers; faded photos; delaminating audio tapes. Most of us have seen what time can do to the media of the moment, when that moment is years, decades or even centuries past.

Preventing such damage is a significant issue for the Library of Congress, which holds millions of books, maps, photos, illustrations and manuscripts in many formats–and preserves them for future use, even if they are also digitized. While many Library divisions have a hand in the maintenance, preservation or recordation of these original materials, the Preservation Directorate is at the heart of the effort. Its expert staff brings science to the task of preserving a given item by keeping it stable, and thereby available for future users; ensuring that the Library’s handling doesn’t hurt it; and finding out what secrets an object may hold.

The Mission: Keep It Usable

The Preservation Directorate’s mission is to assure long-term uninterrupted access to the intellectual content of the Library’s collections. Materials to be preserved range from parchment and paper to glass, fabrics, ceramics, photographs and metals, as well as inks and colorants used on those items. Preservation must occur while still allowing access to the collections.

This daguerreotype plate, created to mimic

those made in the 19th century, can be studied under an electronic microscope to determine its properties. Photo by Abby Brack.

The Preservation Directorate manages several programs to ensure this long-term access. Specialists in the Preservation Reformatting Division prepare collections of brittle material to be reformatted into microfilm or digital files. Staff in the Preservation Directorate’s Conservation Division and Binding and Collections Care Division address how an item is stored: the temperature, humidity, and light conditions of its environment, its enclosures, and its handling, including care taken so labels or other utility marks don’t deteriorate the item.

In addition, staff in both divisions treat the Library’s collections to improve their physical condition. This includes the deacidification of books and paper-based manuscripts–the process of removing acid–which can add centuries to an item’s life.

A recent example of a conservation project was the treatment of an artwork by “outsider artist” Martín Ramírez. Titled “Madonna,” the work was created on pieced-together envelopes. It was discovered tucked into the Library’s papers of designers Charles and Ray Eames, tightly rolled and chewed by insects. With permission from the late Ramírez’s heirs in Mexico, the artwork was cleaned, its holes were expertly patched, and it was flattened and framed. It graced an exhibition at the Library celebrating Mexico in December 2013.

Conservator Heather Wanser treats a rare Korean map. Photo by Richard Herbert.

Out of a Crisis, New Expertise

Modern preservation science is often traced back to the triage methods devised by an ad-hoc team of experts who rushed to Italy from around the world in 1966, following the catastrophic flood of the River Arno in Florence. Ancient artworks, books, manuscripts and other world treasures, soaked in water and silt, required speedy intervention if they were to be saved.

One of the so-called “mud angels” later established the Library’s Conservation Division and the Library’s first preservation laboratory. Today, the Preservation Research and Testing Division (PRTD) in the Preservation Directorate includes a set of recently renovated laboratories in the Library’s Madison Building on Capitol Hill. One is the Optical Properties lab, where new methods of analyzing collection items take place including X-ray diffraction, Raman spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy and use of hyperspectral imaging and X-ray fluorescence and the Physical and Chemical Testing Laboratory, where housing materials are tested to make sure they meet preservation standards. There, conditions of storage areas–sampling of the air for pollutants, for example–can be assessed.

PRTD finds non-invasive ways to assess and preserve collections; devises ways to slow or halt deteriorating factors–such as the “iron gall” ink used in historic manuscripts and the acidity of wood pulp-based papers, which, left untreated, will yellow and crumble.

Scientific Sleuthing

Equipment developed by PTLP is being used by the Library to deacidify books and manuscript pages. Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

Advanced techniques, such as hyperspectral imaging, are making it possible to learn things about centuries-old documents that previously could not be known.

In 2010, PRTD Chief Fenella France–a world-renowned expert in conservation science–made an exciting discovery while using hyperspectral equipment to analyze one of the Library’s top treasures, a draft Declaration of Independence in Thomas Jefferson’s hand. Hyperspectral imaging has allowed the Library to see previously obscured details of the 1791 Pierre L’Enfant plan of Washington, D.C., and four fingerprints on the handwritten draft of the Gettysburg Address.

The Library has also used hyperspectral imaging to establish links between a rare copy of Ptolemy’s 1513 “Geographica,” an atlas with hand-colored maps, and the 1507 Waldseemüller World Map, the first known document to have the word “America” in it.

The Library is able to publicly display the Waldseemüller map and Abel Buell’s 1784 map of the newly independent United States due to hermetically sealed encasements that control humidity and minimize oxygen. The cases were designed and constructed in collaboration with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

“The most challenging part of what we do is knowing that you may be working with the ‘only’ copy, so that’s why the focus is on new non-invasive technologies that can reveal hidden, exciting information about our amazing collections,” said France. “Using current techniques, while looking to new high-tech advances that we can adapt, means we know more about our rare collections than ever before, and without even touching them!”

January 15, 2015

Instrumentally Yours

The late 19th century gave rise to some truly imaginative, public-minded Americans. We all know about the Thomas Edisons, the Henry Fords, the Garrett Morgans. But there were others who, while not household names today, lived very interesting lives and left behind fascinating legacies.

Among these we find Dayton C. Miller, born on a farm in Ohio in 1866, who worked his way through college in his home state and eventually became a professor of astronomy and physics at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. Miller’s was an inquiring mind, and he investigated many aspects of science throughout his life.

But his real devotion – you might even call it an obsession – was wind instruments, specifically flutes.

Flutes and a statuette from the Dayton C. Miller Collection on display this month. Photo by Shawn Miller

He amassed a collection of nearly 1,700 flutes and other wind instruments, plus hundreds of other objects related to the flute: statues, artwork, books, music, trade catalogs, instruction manuals. Then he donated it all to the Library of Congress, shortly before his death in 1941.

Some of the most elegant and interesting objects in this colossal collection are on display in the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building this month, in a trio of glass cases on the first floor.

The display includes several of the rarest and most unusual flutes in the collection – a golden flute, some crafted of glass or crystal and some beautifully carved wooden flutes – as well as a selection of rare recorders and piccolos, including a Sioux tribe “courting flute” with a bird motif. One flute is designed to be used as a walking stick and resembles a wooden branch; there’s a knob at the closed end to grasp for walking and the keys are decorated to look like little branch shoots.

Carol Lynn Ward-Bamford, the Library’s curator of musical instruments, said it was “quite fun” putting the display together. But, she noted, it was a bit “daunting” trying to determine what to choose from such a huge collection. “It’s like going into a toy shop and having to pick from thousands of items,” she said.The display also includes a selection of Miller’s flute-themed statuary from many nations, including a lovely piece of Meissen porcelain.

The ability to view the objects from several angles makes the flute end-caps visible, and that’s something many flute displays don’t afford, Ward-Bamford says. “With these flutes, some of the end-caps are made of beautiful materials – mother-of-pearl or ruby or garnet.”

The Dayton C. Miller Collection also will be the focus of the presentation “Two Thousand Flutes” on May 1 at 2 p.m. in the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium. Ward-Bamford will be joined by Pittsburgh Symphony principal flutist Lorna McGhee and prize-winning piano soloist Ryo Yanagitani for a performance and talk about the Miller flutes; several will also be displayed that day in the Coolidge foyer. The concert is free, but tickets are available through Ticketmaster for a small service fee; to obtain tickets, click here.

If you miss the chance to view the flutes in person, significant portions of the Dayton C. Miller Collection can be accessed online. Here, for example, is a photo of Miller himself playing a special, vertical bass flute known as the “albisiphon,” which he described as having “a very rich and beautiful tone.”

His collection also includes artwork, such as antique prints and woodcuts, showing not only flutes being played but also depicting instruments rarely found today, from an ophicleide (a keyed brass instrument rather like a tuba) and a cittern (like a 10-string bouzouki) to a theorbo (basically, a lute with a lengthy, extended neck).

Researchers can view items in the Dayton C. Miller collection at the Library, by appointment with Ms. Ward-Bamford.

January 13, 2015

Inquiring Minds: The Document Man

Christopher Woods

Armed guards? Check. Secret rendezvous points? Check. Mysterious steel briefcase? Check. Sounds like a James Bond movie. But it’s just a day in the life of Christopher Woods, director of the National Conservation Service in Britain. By day, he’s a leading conservator in the field with more than 29 years experience working in the heritage sector, including serving as head of Conservation and Collection Care at the Bodleian Library at Oxford University and director of Collection and Programme Services at the Tate Gallery in London. By night – well, more like special assignment – he is the man tasked with transporting Lincoln Cathedral’s original copy of Magna Carta when it’s on travel.

The 800-year-old charter, signed by England’s King John in 1215, details the rights and liberties granted to his barons in order to halt their rebellion and restore their allegiance to his throne. The document is widely recognized as influencing America’s own Constitution and Bill of Rights.

Woods deposited the historical document at the Library of Congress in November to be placed on view in the exhibition, “Magna Carta: Muse and Mentor.” The 10-week exhibition closes next Monday, Jan. 19, and Woods will return to pack up his precious cargo for its journey home.

Woods said traveling with Magna Carta is pretty “low key.”

“People don’t know when and where it’s traveling,” he added.

The document is secured in an insulated box system that protects it from temperature change, pressure and movement and flies first class to its destination. Woods quipped that he’s not handcuffed to the steel travel case during transport.

When leaving the U.K. with Magna Carta for his trips abroad, Woods is escorted to the plane.

“Then, in the United States, I’m met by armed guards upon arrival,” he added.

Woods admitted the first few times he traveled with Magna Carta he was nervous.

“There was a time when it was such a relief to get the plane in the air,” he said.

However well traveled he may be at this point, he’s always vigilant, especially considering the planning and work that goes into keeping Magna Carta safe and protected while away from its home at the cathedral.

The charter undergoes an annual inspection, multiple condition reports pre- and post-loan, and lots of photographs are taken, including ones of key areas needing monitoring.

Magna Carta has a special display case specifically for U.S. loans, with features that allow Woods to monitor conditions inside, even while he’s back in Britain, using his smart phone.

Woods explained that humidity control is of utmost importance.

“No man” (as in “No man shall be taken or imprisoned … except by the lawful judgement of his peers …,” clause 39.

“As long as we keep the humidity stable, the ink will remain well-attached,” he said.

Lighting can also impact condition of the document, although Woods explained that as long as there isn’t any ultraviolet light, there isn’t much concern about fading.

“Magna Carta has a light allowance – how many hours of light allowed in any one year,” he said. “In theory, three months out of the year the document is taken off display, which gives it enough allowance to be loaned.”

Woods is tasked with a great responsibility, and having this close a relationship with such an important document isn’t unobserved.

“I’ve learned a lot about Magna Carta as a document, and I’ve learned even more with the Library’s exhibit,” he said. “I’ve learned the importance of the document to its people, and I’ve come to understand my capacity to do the job right.

“It’s important for this original item to be preserved, because there is nothing quite like it. When the real thing is in front of you, it becomes less an academic object and more a talisman. It becomes an icon.”

Join Christopher Woods at 10 a.m. on Jan. 19 in the exhibition, located in the second floor South Gallery of the Thomas Jefferson Building, where he will discuss the care and conservation of Magna Carta.

January 9, 2015

From Dollars to Distinction

I’m a big fan of “Downton Abbey,” so naturally I have been anticipating this season’s series premiere for several months. Following the episode, there was a special on how the show accurately represents the customs and manners of 1900s Britain. If you’re not familiar with “Downton,” the show centers around the wealthy Crawley family, headed by the Earl of Grantham and his multi-millionaire American heiress wife Cora. As it turns out, the idea of an American woman becoming a titled aristocrat isn’t as sensationalized for television as you might think.

The Herald, Los Angeles, Calif., Sept. 21, 1895. Serial and Government Publication Division, Library of Congress.

During the late 19th century, hundreds of rich bachelorettes crossed the pond in hopes of snagging a member of the British aristocracy. At the time, a depression in agriculture threatened the fortunes and estates of the noblemen. The money brought with these “Dollar Princesses,” as they came to be known, provided the much-needed cash to keep the estates and family fortunes afloat. Their dowries were built from the prosperity of Industrialism, where iron and steel manufacturing, oil production and shipbuilding meant big money. In exchange, the American heiresses received social status and a title.

They read pamphlets that identified the European royal bachelors and sought out self-help guides that offered instruction on etiquette of the aristocracy. A quarterly publication called “The Titled American” listed the successfully married ladies, as well as the names of eligible titled bachelors.

These Gilded Age heiresses married more than a third of the titles represented in the House of Lords, and announcements of these transatlantic marriages were pervasive in the newspapers of the day.

Notable names included Jennie Jerome, who married Lord Randolph Spencer Churchill and later gave birth to son Winston Churchill; Nancy Langhorne, who married William Waldorf Astor and later became the first woman to take a seat in the British parliament (her sister Irene married Charles Dana Gibson and became a prototype for the Gibson Girl); and Mary Leiter, whose husband Lord Curzon was appointed Viceroy of India, giving Mary the highest position an American woman has ever held in the British empire. (According to the Daily Mail, she was the inspiration for the character of Lady Cora in “Downton Abby.”)

Duchess of Marlborough. Between 1910 and 1920. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Chronicling America, the Library’s collection of historical newspapers, has no shortage of headlines recounting stories of this turn-of-the-century phenomenon.

An accompanying graphic to the article “She Has Landed Her Duke,” (The Herald, Los Angeles, Calif., Sept. 21, 1895) likens Dollar Princess Consuelo Vanderbilt as “merchandise” and she and her intended, the Duke of Marlborough, as commercial commodities to be traded.

One of Vanderbilt’s bridesmaids, May Goelet, was also much sought after. According to “The Duke of Roxburghe Gets His Heiress-Bride,” (The Pacific Commercial Advertiser, Honolulu, Hawaii, Nov. 11, 1903), her suitors included the Duke of Roxburghe (whom she married), the Grand Duke Boris of Russia, Prince Francis of Teck, Prince Henri of Orleans, Prince Hugo of Hohenlohe, the Prince of Saga, the Duke of Abruzzi, the Duke of Manchester, the Earl of Shaftesbury, Lord Ingestre, Lord Dalmeny and Lord Crichton.

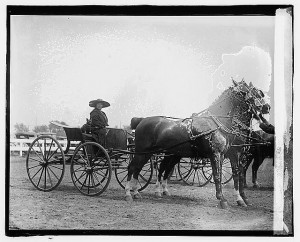

And, in a headline that you just can’t make up, “How the Heiress’s Horses Picked Her Husband,” (The Richmond-Dispatch, Richmond, Va., April 22, 1917) lumber heiress Loula Long measured the worth of her suitors by the reaction of her horses.

“I’m quite sure no man could ever pass muster with me unless he not only loves my dog and my horse, but was loved as well by them,” she said.

Loula Long Combs. 1920. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

While she was courted by such nobility as Prince Ledochowski of Poland and Grand Duke Michael Michaelovitch of Russia, her horses literally lead her to the arms of her husband, Pryor R. Combs, the son of the minister of the Independence Boulevard Christian Church where her family attended services.

“Downton Abbey” is filmed at Highclere Castle in West Berkshire, a real estate that is the country seat of the Earl of Carnarvon. The history of the estate and its real-life inhabitants include the contributions of a dollar princess. The 5th Earl of Carnarvon married Almina Wombwell, illegitimate daughter of millionaire banker Alfred de Rothschild. Her dowry helped sustain the family estate. Most notably, her husband was a key figure in the discovery of King Tut’s tomb in 1922. You can read more about Highclere Castle and the Carnarvon family in the January-February 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Also searching for “Highclere Castle” or “Earl of Carnarvon” in Chronicling America will turn up several articles about the family.

Sources: Smithsonian Magazine; “To Marry an English Lord,” by Gail MacColl and Carol McD. Wallace

January 7, 2015

Library in the News: December 2014 Edition

Every year, the Library of Congress announces the addition of 25 films to the National Film Registry, and we are always excited about the enthusiasm for the selected films and the opportunity to spread the word about our preservation efforts.

The Washington Post reached out to some of the filmmakers for their thoughts on their work being added to the registry.

Mark Jonathan (“Into the Arms of Strangers: Stories of the Kindertransport” [2001]): “The Academy Awards, as everyone knows, are a snapshot of one year. This film’s selection by the National Film Registry means that the movie has had a long life and will continue to going forward.”

In its “Reading the Times With” column, the New York Times featured actress Laura Dern, who said she was “ecstatic” about this year’s list of films.

National outlets running stories included Variety, Los Angeles Times, CBS News, Rolling Stone, The Guardian, CNN, Reuters and PBS Newshour, which featured clips of the films.

Regional outlets in Ohio, Oregon, Michigan, Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas, Florida, Canada, Italy and Germany, among others also highlighted the registry.

Speaking of film preservation, the Library’s Packard Campus for Audio Visual Conservation continues to make headlines.

Martha Teichner of CBS Sunday Morning visited the campus.

“The vaults look like they’re straight out of some sinister, surreal movie,” she said. “Monsters lurk behind these locked doors — like the original camera negative of ‘Frankenstein,’ from 1931, starring Boris Karloff — and treasures.”

During her visit, she was shown a copy of a “CBS Evening News With Walter Cronkite” broadcast from Nov. 8, 1977, which featured her very first story for the network.

“It was, like, nine days after my first day of work,” she said.

In addition to the moving image collections, a large photographic archive – more than 13.7 million – also resides at the Library.

James Estrin of the New York Times Lens Blog spoke with the Library’s Beverly Brannan about photographer Dorothea Lange, whose photographs are part of the Library’s collections.

“She was a humanist,” Brannan said. “She could look at a person’s face and know a lot about that person, and her photos capture something very accurate and meaningful of that person.”

Brannan said that after 40 years at the Library, she is still discovering new things about Lange.

ABC News featured a series of photographs of bulldogs dressed in human attire, taken by an unknown photographer.

The Library welcomes more than 1.5 million visitors each year. Brandon Wetherbee and Jonny Grave of BrightestYoungThings took a whirlwind tour of the institution and wrote a photo essay about their experience.

“We’re inside a building re-built from the shreds of what survived the Burning of Washington two centuries ago,” Grave wrote. “Along with the card catalog cabinets, this building holds the Magna Carta, a Gutenberg bible, George Gershwin’s piano, the only portrait Beethoven ever sat for, and a copy of almost every book ever printed. And I’m shooting as fast as I possibly can.

“What I find most striking about the Library of Congress is not how much they have behind their doors, but how it is all available to the public,” he added. “The Library of Congress is not just an archive, or a compendium of knowledge. All of the knowledge within the very brick and mortar of the building (or archived away in Culpepper, one of the Library’s satellite locations) is meant to be disseminated to the public, for free.”

Also paying us a visit was MLB.com who wrote about the Library’s baseball collections.

“The nation’s greatest storehouse of knowledge has developed a healthy baseball habit,” wrote Spencer Fordin. “The Library of Congress has traced the history and maturation of America for more than 200 years, and baseball has weaved its way into the national consciousness in surprising ways.”

Leading the way for the Library’s initiatives and innovations is Librarian of Congress James H. Billington.

“The 85-year-old scholar has been one of the country’s most aggressive advocates, moving the resources of the library online and expanding its educational outreach through 21st century technology,” wrote Maria Recio for McClatchy News Service. “Billington is, quite simply, a keeper of American culture, not just the keeper of books. He is charged with preserving the past while also expanding the library’s reach by keeping it tune with the moment – in music, in film, in various forms of human literary and artistic expression.”

December 26, 2014

Sensationalism! Yellow Journalism! More, More, More!

It’s the day after Christmas, ho-ho-ho-hum. The presents are already open, your elbows are getting rubbed a little raw with all these relatives around, and you’re sick of holiday cookies and candy and fruitcake. It’s all too tempting to jump on the old cellphone and see what snarky things are being said on social media, or flip on the tube and see what they’re saying on TMZ.

WWI put the year 1914 six feet under

Stop! You can do that anytime. Instead, go to the website “Chronicling America” and check out a newspaper that is 100 years old today – the Philadelphia Evening Ledger of Dec. 26, 1914. There was a lot going on, even though the day being reported on was Christmas:

World War I, from “Peace for an Hour as Soldiers Pray on Battlefields” to “Czar Breaks German Line: Gains Ground in Poland”

Pancho Villa was on the move: “Villistas Drive Defenders Back Near Vera Cruz”

Really peculiar cartoons were being published;

The sale of the New York Yankees was pending;

Washington, D.C., experienced a small earthquake on Christmas Eve, at 10:51 p.m. ;

A religious revival was slated, by the famous baseball-player-turned-preacher, Billy Sunday;

The doings of every service club in Philly were noted, from the Royal Arcanum to the Artisans Order of Mutual Protection

And, you can read episode IV of a piece of fiction: “Zudora, A Great Mystic Story by Harold MacGrath.” (Not to worry – it has a synopsis).

Old newspapers are addictive. Predating TV, radio and (of course) the internet, they were the go-to public source for entertainment. They do, in fact, serve up “history as it is being written,” but they also show you what our society was like at a brief moment in time. The ads are fascinating (“Newton Coal Answers the Burning Question!” “First Canaries Since the War Arrive on Steamer Sloterdyk from Rotterdam!”). Just looking at the differences and the similarities in what was considered news is fascinating. You can get lost in these old papers. My grandpa Phil, on my mother’s side, served in the U.S. Army infantry in WWI; he probably was in some of the battles reported in this newspaper (after the U.S. got in, of course). These are the kinds of papers he, and my grandma, and their parents would have been getting all of their news out of.

Chronicling America, which offers digitized copies of thousands of newspapers of yore, is a site backed by the Library of Congress and the National Endowment for the Humanities. In addition to the huge trove of searchable papers it offers, the site also selects several papers 100 years old today for your perusal, daily.

Old news is good news. Check it out.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers