Library of Congress's Blog, page 147

April 24, 2015

Happy 215th Anniversary Library of Congress!

A Message from the Librarian

Today, on the Library of Congress’s 215th anniversary, I want especially to congratulate the Library’s extraordinary staff for their work in building this amazing, one-of-a-kind institution.

I am, and always will be, deeply grateful for all they do.

The heart and soul of this great library always has been its multitalented and dedicated staff that has served Congress and the American people in ways unequaled by any other institution.

The Library possesses the largest and most wide-ranging collection of recorded knowledge ever assembled – a statement of fact that, somehow, still fails to convey the breadth of the service this institution provides.

The Congressional Research Service produces the authoritative, nonpartisan analysis and research Congress needs to perform its constitutional duties, and we also support Congress through the work of the nation’s largest law library.

The U.S. Copyright Office protects and preserves the sole depository of the intellectual and cultural creativity of the American people. The National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped provides the only free public library reading service for blind and visually impaired Americans, wherever they live.

The Veterans History Project collects and preserves firsthand accounts of our veterans’ wartime service and makes them available to the public so that all may know their stories and sacrifices. The World Digital Library gathers great examples of cultural achievements from around the world and presents them, in seven languages, to a global audience.

As the de facto national library of the United States, the Library acquires, preserves and makes accessible – free of charge – the largest and most-diverse accumulation of curated knowledge and creativity in history.

This magnificent accomplishment has been made possible by the continuous support of the U.S. Congress, the greatest patron of a library in history, and by the exceptional work of the dedicated and long-serving Library staff.

Whether working at the heart of the Capitol Hill complex, the NLS offices on Taylor Street, the film- and recorded-sound-preservation facilities in Culpeper, the storage facilities in Landover or offices scattered around the globe, individuals collectively make the Library the great institution it is.

At our Cairo offices, director William Kopycki and his staff acquire important, hard-to-get primary materials from developing nations for the Library’s own collections and those of other U.S. and global research institutions. The Cairo office – like those in Islamabad, Jakarta, Nairobi, New Delhi and Rio – carries out its mission in the face of great challenges: war, terrorism, political unrest, censorship, poverty, huge geographic distances.

At NLS, John Hanson, head of the Music Section, helps make music possible again for thousands of visually impaired musicians. The Music Section provides the public with access to the world’s largest source of braille music material – a lifeline for visually impaired musicians who otherwise might not be able to pursue their dreams.

In the Preservation Directorate, book-binder and collections conservation expert Nathan Smith carries out a combination of art and science – repairing bindings, filling paper tears, re-creating beautiful bindings and making special preservation boxes – that helps preserve historical materials for future generations.

In the Veterans History Project, director Robert Patrick and his staff for 15 years now have collected and preserved the individual stories of America’s wartime veterans, from the last living veterans of World War I to the dwindling generations of World War II and the returning veterans of recent conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq. To date, more than 96,000 such oral histories have been archived at the Library.

Lee Ann Potter and the Educational Outreach team show teachers and librarians across the country – both in-person and online – how to incorporate the Library’s incredible trove of digitized primary-source material into K-12 curricula. In the last fiscal year, for lifelong learning both onsite and online, the Educational Outreach team and its Teaching with Primary Sources partners delivered primary-source professional development to 23,196 teachers in 374 congressional districts.

And through their “Mostly Lost” programs, Rob Stone and Rachel Parker of the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division have helped identify scores of silent films whose titles had been lost to history – and, in doing so, help preserve the nation’s motion-picture heritage.

These are but a few examples of the countless, important service activities performed here each day – cataloging, reference services, copyright registration, security, visitor services and many others. Collectively, our curators, docents and volunteers are greatly increasing the number of visitors to the Library and its exhibitions. The Library is an irreplaceable asset to the United States and the world’s pre-eminent reservoir of knowledge.

As we celebrate this 215th anniversary, the Library’s staff members can be proud of this institution’s historical record of service to Congress and the American people and their own contributions to it.

With appreciation and happy birthday wishes,

James H. Billington

Librarian of Congress

(The story was also featured in the Library of Congress staff newsletter, The Gazette.)

April 23, 2015

We’ve Got Style

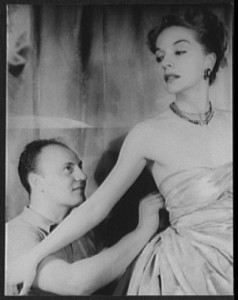

Portrait of Pierre Balmain and Ruth Ford making a dress. Photo by Carl Van Vechten, Nov. 9, 1947. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Every year, top fashion designers, style bloggers and journalists, celebrities and other movers and shakers gather in chic cities across the globe to showcase and check out the latest styles in clothing, accessories, hair and even makeup.

Fashion shows for Autumn/Winter womenswear is usually held in February, with the Spring/Summer looks being exhibited in September. Bridal Fashion Week kicked off April 15 in New York City.

I myself love fashion and giddily peruse the reviews and images that highlight the best and worst of the participating designers. The creativity and sometimes audacity of their styles has me both wanting to go shopping while wondering how one is supposed to actually wear what they are showcasing. If anything, noticing fashion trends is really a lesson into our own culture and history, how our tastes have evolved over time and how we are inspired and influenced by our own surroundings.

Anna Wintour, famed editor of Vogue Magazine, once said, “One doesn’t want fashion to look ridiculous, silly, or out of step with the times – but you do want designers that make you think, that make you look at fashion differently. That’s how fashion changes. If it doesn’t change, it’s not looking forward.”

The Library of Congress recently launched a fashion-related Pinterest board, which surveys fashion trends from yesteryear. Represented are styles for men, women and even children – from fancy dress to hats to hosiery (“the new fashion trend” of having hose blend in with the color of your dress.

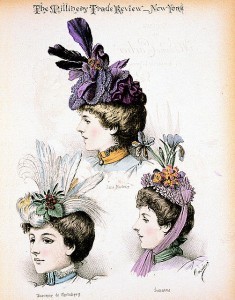

Modelès de Madame Carlier. 1897. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

What’s interesting to notice is how trends have changed and the historical evidence of cultural and societal shifts. Pointed out are variations in hairstyles, makeup, accessories, hemlines, heel heights and colors. Women wearing hats and gloves may tell us about the formality or modesty of an era. Images of women reveal revisions in desired body shape over time. Material for clothing may vary with tariffs, rationing or new technologies. Children’s clothing reflects shifts in concepts of childhood.

The Library has a large collection of fashion magazines and pattern books that can help further trace the evolution of fashion. You can observe clothing styles appropriate for different years, seasons, activities, age levels, and classes in long runs of titles such as Harpers Bazaar, which dates back to 1867; McCall’s Magazine (1897-2001), Vogue (1892-present) and Butterick Fashions (1931-1957).

The Butterick Publishing Company also produced The Delineator, a women’s magazine of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It provided its readers with sewing patterns and stories on current fashions. This January 1926 issue features patterns from Paris, advice on the home gymnasium and a story on how to find beauty.

For further reading, check out this guide to the fashion industry from the Science, Technology and Business Division. It represents a selection of the many resources in the Library of Congress that may be useful for the study of this topic.

April 22, 2015

A Day of Mourning

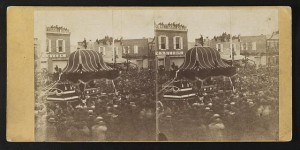

President Abraham Lincoln’s railroad funeral car. Photo by S.M. Fassett, 1865. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

This month marks the 150th anniversary of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. The 16th president was shot by John Wilkes Booth the evening of April 14 and died nine hours later on April 15.

Several days later, Lincoln’s body would begin its long train-trek home to Springfield, Ill., where he would be buried on May 4. Departing April 21, 1865, from Washington, D.C., his funeral procession would travel 1,654 miles through 180 cities and seven states. Nicknamed “The Lincoln Special,” the nine-car funeral train would essentially travel the same tracks that carried the then President-elect east in 1861. Follow the journey with this special presentation in the Library’s Lincoln Bicentennial exhibition.

Lincoln’s coffin was taken off the train at each stop and placed on a horse-drawn hearse that rode through the city to a place the public could pay their respects. Throngs of people lined the streets to watch the funeral procession. Millions more lined the train tracks as the slain president made his final journey home.

The sorrow of the nation was palpable in reports from newspapers across the country.

items in the collection relate to Lincoln’s funeral, including music, newspaper articles, mourning cards, funeral programs and more.

items in the collection relate to Lincoln’s funeral, including music, newspaper articles, mourning cards, funeral programs and more.

April 20, 2015

Young Gun

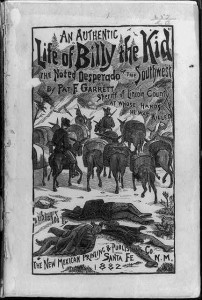

Cover of Pat F. Garrett’s “An Authentic Life of Billy the Kid.” 1882. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

In 1882, Sheriff Pat Garrett published his account of the apprehension and death of Billy the Kid, whom he shot and killed on July 14, 1881.

“‘The Kid’ had a lurking devil in him; it was a good-humored, jovial imp, or a cruel and blood-thirsty fiend, as circumstances prompted. Circumstances favored the worser angel, and ‘The Kid’ fell,” Garrett wrote in “The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid.”

Marshal Ashmun Upson, a friend of Garrett who was also a newspaper journalist, actually ghostwrote the book.

In the fifth version of the book it was noted in an introduction by J. C. Dykes: “Garrett and Upson became very close friends, and this friendship endured until Upson’s death at Uvalde, Texas, in 1894. He was buried there in a cemetery lot owned by Pat Garrett. Garrett and Upson – friends and a writing team that produced a remarkable book.”

According to Garrett in the introduction to his book, “I am incited to this labor, in a measure, by an impulse to correct the thousand false statements which have appeared in the public newspapers and in yellow-covered, cheap novels.”

Historians have criticized Garrett’s account as inauthentic and biased, suggesting that he wrote the book to improve his image. However, while the book sold few copies when it was published, it remained an important reference for future historians and would turn the Kid into a legendary figure of the West. The Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division holds one of the rare copies of Garrett’s book.

Statue of Billy the Kid in the arts district of little San Elizario, near El Paso, Texas. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith, Feb. 15, 2014. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Billy the Kid – also known as William Henry McCarty (his actual name), William H. Bonney and William (or Kid) Antrim – was born in New York City about 1859. As a young teenager, he moved with his family to New Mexico, by way of Kansas and Colorado. Following the death of his mother, McCarty was soon displaced and began his descent into a life of crime.

In 1875, the Kid was arrested for the first time for being caught with a stolen basket of laundry. He later broke out of jail – his first jailbreak of several. On the lam, the fugitive continued to steal his way through Arizona and Mexico, including thieving horses and cattle.

In 1877, Billy the Kid joined up with a rough gang and became a key figure in the 1878 Lincoln County (New Mexico) War, which was essentially a feud between established town merchants and competing business interests. During the war, he and his gang, The Regulators, killed Sheriff William J. Brady and Deputy George W. Hindman.

Francisco Trujillo, one of the Lincoln County Regulators, gives an account of his encounters with Billy the Kid in a collection of manuscripts from the Federal Writers’ Project at the Library of Congress.

In addition, this account of Ella Bolton Davidson goes further into the final battle of the Lincoln County War and murder of Sheriff Brady.

The young gunslinger’s crimes earned him a bounty on his head, and he was eventually captured, convicted of murder and sentenced to hang before he made his dramatic escape from the Lincoln County jail on April 28, 1881. In the process he killed two prison guards, Bob Ollinger and J.W. Bell.

Newspapers reported him making his escape saying, “I am fighting the whole world for my life, and I mean business.”

Old Lincoln County Courthouse and Jail, where Billy the Kid was held. Photo by James Rosenthal, 2005. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Billy the Kid was reported to be responsible for the murder of 21 men by the time he was 21 years old (the actual number was likely around 10). Newspaper articles of the time recounted his crimes, with the body count anywhere from 11 to 19 to 36. Such papers as the Las Vegas Gazette often carried news of his exploits.

He avoided capture until July 14, when he was ambushed and killed by Sheriff Pat Garrett at a ranch house. Billy the Kid is buried in Fort Sumner, N.M.

This article from the July 26, 1881, issue of the Omaha Daily Bee gives an account of the night Garrett shot Billy and includes Garrett’s report to the governor of New Mexico.

Some papers aggrandized the exploits of the young gunslinger, such as this article, reprinted from the Pennsylvania Times. The “correspondent” allegedly made an acquaintance with someone who had a “wonderful experience with the celebrated bandit.”

In response, other papers ran stories criticizing the Times article.

“He needs no bogus silver spurs stuck on his heels by a Philadelphia scribbler to send him galloping down to a bloody and dare-devilish immortality in the annals of this strange, wild territory.”

Sources: history.com, pbs.org, “Billy the Kid: A Short and Violent Life,” by Robert Utley

April 16, 2015

The Power of a Poem

(The following is an article from the March/April 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. Editor Audrey Fischer wrote the story. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

This portrait of Billie Holliday performing in a New York nightclub appeared in Down Beat magazine in 1947. William P. Gottlieb, Gottlieb Collection, Music Division.

Billie Holiday’s iconic song about racial inequality was penned by a poet whose works are preserved at the Library of Congress.

Recorded in 1939, Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” brought the topic of lynching to the commercial record-buying public.

Few may be aware that the song was based on a poem written several years earlier by Abel Meeropol (1903-1986), a Jewish high-school teacher from the Bronx, who was deeply affected by a 1930 photograph of a lynching.

Born in the Bronx, Meeropol attended DeWitt Clinton High School, where he later taught English. The school’s other notable creative alumni include James Baldwin, Countee Cullen, Richard Rodgers, Burt Lancaster, Stan Lee, Neil Simon and Ralph Lauren.

Meeropol published most of his work under the pseudonym “Lewis Allan,” in memory of the names of his two stillborn children. In 1937, his poem originally titled “Bitter Fruit” was published under his given name in the Teachers’ Union publication “The New York Teacher” and under his pen name, in the Marxist publication “The New Masses.”

Meeropol later set it to music and gave it to the owner of Café Society, an integrated cabaret club in New York’s Greenwich Village. The club owner shared it with Billie Holiday, one of the club’s regular performers, who sang it at the end of a set in 1938–to a stunned audience. She recorded it the following year under the title “Strange Fruit.” In 1999, Time magazine named “Strange Fruit” the song of the century. In 2002, it was selected for preservation in the inaugural National Recording Registry.

Abel with wife Anne Meeropol, the first person to sing “Strange Fruit” in public, circa 1935. Courtesy of Michael and Robert Meeropol.

Like many who railed against social injustice during the 1930s, Meeropol was a member of the Communist party. At a Christmas party at the home of civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois, Meeropol and his wife were introduced to the young children of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, a couple convicted of conspiracy to commit espionage. The children were orphaned when their parents were executed in 1953 at the height of the McCarthy Era. A few weeks later, the children were sent to live with the Meeropols and took their last name.

Meeropol, who taught until 1945, continued to write songs for such artists as Peggy Lee and Frank Sinatra. One of his more well-known works, “The House I Live In,” was sung by Sinatra in a 10-minute short film written by Albert Maltz. The 1945 film, which was made to oppose anti-Semitism and racial prejudice at the end of World War II, received an honorary Academy Award and a special Golden Globe award in 1946. In 2007, it was added to the list of films selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.

April 13, 2015

The Golden Fleecer

Who the devil was Soapy Smith?

Some would say the devil was Soapy Smith.

He was a swindler, a con artist, a bunco steerer. In the 1880s and ’90s he fleeced rubes from Denver to Skagway, Alaska and at many points in-between. He was dubbed “Soapy” because an early con involved selling overpriced soap by tricking gullible passers-by into believing $50 and $100 bills were wrapped around some of the bars under their paper wrappings. He also knew the pea-under-the-shell game and three-card monte.

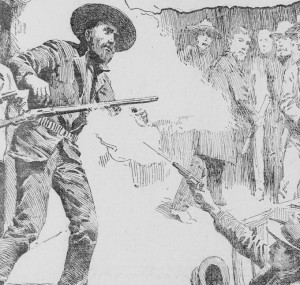

Artist’s rendering of Soapy Smith, gunned down by a Skagway vigilante

Here’s how his patter ran, according to authors William Ross Collier and Edwin Victor Westrate in “The Reign of Soapy Smith, Monarch of Misrule”:

“Wake up! The hour has come to face the problems of our country! … One question–the supreme question–before us today is vital to the welfare of the republic! Gentlemen, the all-important question which I propound to you and for which I earnestly seek the answer is this:

How are you fixed for soap?”

When Denver launched a petty-crime crackdown, Soapy and his gang decamped to–and effectively took control of–Creede, a silver-mining boomtown memorialized by its resident poet-and-newspaper-editor, Cy Warman:

Here’s a land where all are equal–

Of high or lowly birth –

A land where men make millions

Dug from the dreary earth.

Here meek and mild-eyed burros

On mineral mountains feed,

It’s day all day in the day-time

And there is no night in Creede.

Nightless as it may have been, after the sun went down, Soapy and his gang had many ways to flimflam one hapless schmo after another in his saloon, the Orleans Club (where, as Warman noted in verse, “everything was open wide/ and men drank absinthe on the side”). But Soapy had a reputation as a Robin Hood in some quarters, which was referred to, tongue-in-cheek, by the San Francisco Call:

“‘Soapy’ was not altogether bad at heart. He had been known to hand out to a less fortunate man the entire profits derived but a short time previous by knocking some Reuben on the head and ravaging his pockets.”

The journalist Richard Harding Davis went to Creede and had a chance to observe Smith in 1892, leading to this passage in Davis’ book “The West From a Car Window,” illustrated by artist and later, world-famous sculptor Frederic Remington:

“”Soapy” Smith … was a very bad man indeed, and hired at least 12 men to lead the prospector with a little money, or the tenderfoot who had just arrived, up to the numerous tables in his gambling-saloon, where they were robbed in various ways so openly that they deserved to lose all that was taken from them.”

Pickings were rich in Creede until the Silver Panic of ’93 turned many “mushroom towns” of the Colorado Rockies into spores blowing on the winter wind.

Cy Warman versified about that, too:

And now the Faro Bank is closed

And Mr. Faro’s gone away

To seek new fields, it is supposed, —

More verdant fields. The gamblers say

The man who worked the shell and ball

Has gone back to the Capitol.

Yes, he was writing about Soapy, who with his minions returned to Denver and had some large-scale misadventures: the governor had to call out the National Guard on Soapy when he was holed up in City Hall with his paid-off bureaucrats; Smith tried to start a sort of Foreign Legion of expatriate U.S. toughs in Mexico; and he planned a takeover of the town of Cripple Creek, which was foiled. Then he lit out for Skagway, where gold had been found in 1897.

And there, after a few lively months running a gambling hall and again effectively running the town by bribing the local cops, Soapy found the hail of gunfire that would kill him, at the hands of vigilantes on July 8, 1898. Smith’s exit made front-page news all over the nation.

The Library of Congress holds many collections that bring America’s Wild West heritage into sharper focus, ranging from the Chronicling America online collection of historic newspapers to photos, manuscripts and, of course, books.

April 9, 2015

Library in the News: March 2015 Edition

Headlining Library of Congress news for March was the announcement of new selections to the National Recording Registry.

Time called this year’s selections the “most American playlist ever.”

“If the Smithsonian is America’s attic, the National Recording Registry is the dusty box of records that America’s parents left up there,” wrote reporter Ryan Teague Beckwith.

Ben E. King of “Stand By Me” fame (which was one of the selections this year) told CBS News that having his song included in the registry “is one of the greatest moments of my life.”

Voice of America spoke with Christopher Cerf, co-producer and composer of some of the songs on “Sesame Street: Platinum All-Time Favorites,” which made the registry this year.

He said it was an honor and that he felt “incredibly lucky” to be a included in the registry.

Other outlets running the story included USA Today, Rolling Stone, Entertainment Weekly, Variety, NPR, BBC, LA Times, Associated Press (print and broadcast), The Washington Post, PBS NewsHour, ABC News, BET and a variety of local news outlets across the country.

Also receiving praise for her work was author Louise Erdich, who was awarded the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction.

Erdrich told Alexandra Alter of the New York Times Artsbeat blog that receiving such awards feels like “an out of body experience.”

“It seems that these awards are given to a writer entirely different from the person I am — ordinary and firmly fixed,” she said. “Given the life I lead, it is surprising these books got written. Maybe I owe it all to my first job — hoeing sugar beets. I stare at lines of words all day and chop out the ones that suck life from the rest of the sentence. Eventually all those rows add up.”

“In addition to the Library of Congress, I have my parents Rita and Ralph, in whom my grandparents’ spirits are still vital, to thank for this recognition,” Erdrich told Fine Books & Collections Magazine.

In other news, the Library opened a new exhibitions in March: “Pointing Their Pens: Herblock and Fellow Cartoonists Confront the Issues.”

Running an announcement was The New York Times.

Also garnering attention was the Library’s exhibit on theatrical design, which opened in February.

“In the performing arts, stage design often goes overlooked while the audience is captivated by the completely immersive experience of actors, scene, music, and costumes. The current Library of Congress exhibition ‘Grand Illusion: The Art of Theatrical Design’ showcases this essential craft,” wrote Allison Meier for hyperallergic.com.

Speaking of Library exhibits, President Barack Obama and his daughters stopped by the Library in March for a special viewing of Lincoln’s second inaugural address, which was on view for four days early in the month. The Washington Post covered the visit.

April 8, 2015

That All May Read

(The following is a guest post by Karen Keninger, director of the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped.)

There are times when a “best-kept secret” is exactly what you want. But not when it comes to one of the most highly valued services provided through the Library of Congress – namely the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped (NLS).

Digital talking-book players are available in basic and advanced models.

This free public library service provides books and magazines in braille and talking-book formats to half a million residents of the United States and U.S. citizens living abroad who can’t read standard print because of visual or physical disabilities. However, statistics indicate that even more Americans could benefit from the service if they only knew about it.

That’s why NLS has launched a public education campaign to spread the word about NLS and its network of more than 100 cooperating libraries throughout the U.S. and its territories. We particularly want to inform people who are students, veterans or seniors who either cannot see well enough to read print or who have physical disabilities that make it difficult for them to handle a book or access print in other ways. Our goal is to make sure that all may read, regardless of disability.

The first completed portion of the campaign is a new set of web pages presenting information about NLS and a video featuring NLS patrons describing their experiences with the Library of Congress braille and talking-book program. The video is accessed through the Library’s new, accessible video player and is narrated by Kate Kiley, a veteran NLS narrator.

The new pages form the hub of a digital marketing campaign that will include digital media such as banner ads and text ads and search engine optimization. We also plan to use Facebook and YouTube, with video accompanied by audio description and text files.

NLS has a long history of using technology to meet the needs of our readers. In 1934, when vinyl records were the cutting edge of technology, NLS developed the talking book by recording narrations of books and distributing them on vinyl records. While most records were spun at 78 rpm at the time, NLS slowed it down so more minutes of recording would fit on a single disc. NLS also gave its patrons the talking-book machine, a record player capable of playing the unusually slow 33-1/3 rpm format of talking books. As vinyl technology improved, so did talking books, packing more and more onto smaller records until the advent of the cassette in the late 1960s edged out the vinyl.

Today the cassettes have been replaced with state-of-the-art digital technology, giving patrons the option of receiving their books on flash-memory-based cartridges for use in the latest version of the NLS talking-book machine or of downloading their books directly to play on their smartphones or tablets.

NLS has a lot to offer. Whether a patron chooses to receive books free through the mail or download them from NLS’s Braille and Audio Reading Download (BARD) site, and whether they choose to play the books on the latest version of the talking-book machine or on their smartphones or tablets using the BARD Mobile app, the talking book with human-voice narration is the centerpiece of the service. Talking books provide millions of hours of listening enjoyment to NLS patrons every year. And for those who want to read instead of listen, we provide books in braille. Braille can also be received through the mail or downloaded from BARD or BARD Mobile as digital files to be played on refreshable braille devices.

Young patron reads at bedtime using her smartphone.

Braille and talking book titles cover the gamut of subjects you would find in a public library – from true crime to romance, westerns to world history. And they cover all ages, from six-minute-long tales for kids to full-blown sagas for seniors.

One of the most oft-repeated comments we hear from patrons is, “I wish I’d known about this five years ago.” So we’re working hard to spread the word. The new web pages are the beginning of a focused effort. They will direct visitors to additional resources, contact information, eligibility criteria and application forms. Help us spread the word that all may read.

April 7, 2015

National Poets

(The following is a story written by Peter Armenti, literature specialist for the Digital Reference Section, found in the March/April 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

The nation’s most acclaimed poets have helped the Library of Congress promote poetry for nearly 80 years.

The highest poetry office in the country belongs–both literally and symbolically–to the U.S. Poet Laureate. Headquartered at the Library’s Poetry and Literature Center in the attic of the Thomas Jefferson Building, the Poet Laureateship is the only national position dedicated to raising awareness and appreciation of poetry among the American public.

FROM CONSULTANT TO LAUREATE

From left, poets Allen Tate, Léonie Adams, T.S. Eliot, Theodore Spencer and Robert Penn Warren attend the annual meeting of the Fellows of the Library of Congress in American Letters, November 1948. Prints and Photographs Division.

Originally established in 1936 as an endowed Chair of Poetry in the English Language, the position, as conceived by Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam, was created to build the Library’s literary collections and encourage their public use. The Library’s Consultant in Poetry, in other words, was expected to perform duties today carried out by full-fledged librarians. This is reflected in a memo to poet Allen Tate (1943-1944) outlining his duties, which were limited not to only poetry but to “all English and American literature.” Tate was appointed by Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish, himself a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet.

During the next 50 years, less emphasis was placed on requiring the Consultant in Poetry to develop the Library’s collections and more on organizing local poetry readings, lectures, conferences and outreach programs. A defining moment came in 1985, when Sen. Spark M. Matsunaga’s two-decade campaign to create a national Poet Laureate position resulted in an act of Congress (Public Law 99-194), which changed the consultant’s title to “Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry” and charged the Librarian of Congress with making the selection.

In 1986, Robert Penn Warren became the first poet appointed under the new title, having been the Library’s third Consultant in Poetry more than 40 years earlier. Howard Nemerov (1963-1964; 1988-1990) and Stanley Kunitz (1974-1976; 2000-2001) also have the distinction of serving twice, each having been appointed Poetry Consultant and Poet Laureate.

“The Poet Laureate post is an honor, not a job,” said Pinsky.

By including “Poet Laureate” in the title, the position became the American equivalent of the well-known and longstanding position of British Poet Laureate. As a result, the visibility of the office, along with expectations for it, ballooned. Librarian of Congress James H. Billington described the Poet Laureate as “the nation’s official lightning rod for the poetic impulse of Americans.” Dr. Billington has appointed all but two of the 20 Poets Laureate. In June 2014, he appointed Charles Wright the 20th Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry.

PROMOTING POETS AND POETRY

Seven Poets Laureate Consultants in Poetry returned to the Library for a reading in the Coolidge Auditorium to celebrate publication of “The Poets Laureate Anthology.” From left: Librarian of Congress James Billington; Carolyn Brown, former director of the Office of Scholarly Programs; and poets Mark Strand, Charles Simic, Kay Ryan, Maxine Kumin, Daniel Hoffman, Rita Dove and Billy Collins, 2010. Photo by Abby Brack Lewis.

Fostering the work of promising poets has long been an interest, if not a responsibility, of the Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry. Each year the Poet Laureate selects two or more poets to receive the Witter Bynner fellowship.

The fellows are recognized at a reading in the nation’s capital and go on to organize local poetry readings in their own communities.

Administered by the Library of Congress, the fellowship is sponsored by the Witter Bynner Foundation for Poetry. Harold Witter Bynner (1881-1968) was a prolific poet and philanthropist who made provisions for a poetry foundation after his death. The Witter Bynner Foundation for Poetry was incorporated in 1972 in New Mexico to provide grant support for the writing of poetry through nonprofit organizations. Since its inception in 1998, 37 poets have received the Witter Bynner fellowship, including the recently selected 2015 winners.

POETRY PROJECTS

Per the legislation establishing the office, the Poet Laureate is appointed solely on the basis of a poet’s lifetime literary achievement and has few official responsibilities. However, many Poets Laureate have used the prestige and resources conferred through the position to launch initiatives, and sometime large-scale projects, that seek to introduce–or reintroduce–people to the value of poetry in their everyday lives.

Joseph Brodsky (1991-1992) developed the idea of providing poetry in public places–supermarkets, hotels, airports, hospitals–where people congregate and “can kill time as time kills them.”

Rita Dove (1993-1995) brought together writers to explore the African diaspora through the eyes of its artists, and also championed children’s poetry and jazz through multiple events.

Robert Hass (1995-1997) sponsored a major conference on nature writing, “Watershed,” which continues today as a national poetry, art and environmental impact competition, “River of Words,” for elementary and high school students.

Billy Collins (2001-2003) encouraged the nation’s high-school students to read a poem a day during the 180-day school year.

Kay Ryan (2008-2010) reached out to the nation’s community-college students and professors through a poetry-writing contest and a video conference featuring tips about writing poetry and aspects of her own writing process.

A number of Poets Laureate, such as Robert Pinsky, Ted Kooser and Natasha Trethewey, have also developed poetry projects with unprecedented scope.

Robert Pinsky, who served an unprecedented three terms (1997-2000), issued a national call for people to send him their favorite poems, along with their justifications. Pinsky received more than 18,000 submissions to his Favorite Poem Project. Selected submissions were subsequently gathered into three poetry anthologies.

The centerpiece of the project was the development of 50 video documentaries featuring people reading and discussing their favorite poems. The videos, which aired as segments on PBS’s “The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer,” can be viewed on the Favorite Poem Project website and are a permanent part of the Library’s Archive of Recorded Poetry and Literature. The project endures today, with six recent videos featuring the favorite poems of Chicagoans and plans for more videos in the future.

Ted Kooser (2004-2006) initiated the American Life in Poetry Project to introduce poetry to a broad range of readers through his free weekly poetry column in newspapers and online publications. Each column consists of short poems that an average reader can understand and appreciate, along with a few introductory words from Kooser. The project, which continues after a decade and more than 500 columns, has been immensely successful in reaching millions of readers each week.

Natasha Trethewey (2012-2014) participated in “Where Poetry Lives,” a series of reports with PBS “NewsHour” Senior Correspondent Jeffrey Brown, which uses poetry as a framework through which to view important issues facing American society. Stories featuring Trethewey have ranged from a profile of the Alzheimer’s Poetry Project in Brooklyn, N.Y., which seeks to help victims of dementia engage their memories through poetry and other forms of language play, to a visit with troubled teens in King County Juvenile Detention Center in Seattle, Wash., who work with the nonprofit Pongo Teen Writing Project to express themselves by turning their stories into poetry.

Future Poets Laureate will remain free to shape the position. But one thing is certain: the Poet Laureateship will continue to serve as a national symbol of the government’s commitment to honoring, promoting and preserving a place for poetry in American society.

April 3, 2015

Pics of the Week: Honoring Rosa Parks

U.S. Rep. John Conyers looks over his remarks with Elaine Steele, longtime friend of Rosa Parks. Photo by Shawn Miller.

The Library of Congress presented a special program on Tuesday to honor the Howard G. Buffett Foundation for loaning the Rosa Parks Collection to the Library. A special guest was U.S. Rep. John Conyers, who employed Rosa Parks in his Detroit congressional office for 22 years.

Conyers described Rosa Parks as a quiet, humble person with a beautiful personality. He told the story of how one day she came to him and said:

“‘I’d like to ask for a pay reduction.’ I said ‘I beg your pardon? Nobody’s ever asked for that before.’ Nobody’s ever asked for it since. I said, ‘A pay reduction? Rosa Parks what are you talking about?” She said ‘Well, you know how you let me go to so many places in the country and even overseas. I feel I should have a reduction and I ask you to do that.”

“I said ‘Mrs. Parks, you honor me by coming to my office and having worked with me for so long.’ It was no secret that more people came to see Rosa Parks in my office than came to see me. That’s an example of the kind of person she was.

“For our government and our Library to raise her to this height makes me very, very proud of all of you,” Conyers said.

Philanthropist Howard G. Buffett speaks during the ceremony honoring him for his purchase and loan of the Rosa Parks Collection to the Library. Photo by Shawn Miller.

The Rosa Parks Collection is on loan to the Library from the Buffett Foundation for 10 years. During the event, Buffett also spoke and described how he came to acquire the collection.

According to Buffett, he had been watching the evening news and heard about the materials sitting in boxes in New York for 10 years.

“I thought, ‘that’s crazy. How can that be right?'” he said. He told his wife that his foundation should look into buying the collection, make sure it got preserved and put it somewhere for people to see.

It wasn’t until a woman from Florida – Patricia O’Toole – wrote to Buffett encouraging his foundation to buy the Parks collection and place it in good hands that he decided to act.

“I’m glad Patricia O’Toole wrote me that letter,” he said. “This is just the right thing to do.”

U.S. Rep. John Conyers looks over items from the Rosa Parks Collection. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Buffett ending his remarks by saying that he travels a lot around the world: “Everybody wants to come to America. Everybody wants to come to the United States. There is a huge reason for that. There are many, but one is freedom and that is what Rosa Parks represents – freedom.”

Several items from the Rosa Parks collection are included in the Library’s ongoing major exhibition “The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom,” which is open through Jan. 2, 2016. Later this year, selected collection items will be accessible online.

Donna Urschel, Public Affairs Specialist in the Office of Communications, contributed to this report.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers