Library of Congress's Blog, page 148

April 1, 2015

The Library in History: Love in the Stacks

(The following is a story written by Audrey Fischer for the March/April 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

A bust of Rebekah Johnson Bobbitt by sculptor David Deming was presented to the Library in 1998 to mark the 10th anniversary of the Bobbitt Prize. Photo by Shawn Miller

A romance that began at the Library of Congress in the 1930s led to the creation of a national poetry prize.

Several years before former president Lyndon Baines Johnson’s 1937 election to the U.S. House of Representatives from the state of Texas, his younger sister Rebekah was pursuing a Washington career of her own. While in graduate school, she worked in the cataloging department of the Library of Congress. Her co-worker, Oscar Price Bobbitt, had also come to Washington from Texas–on a train ticket bought by the sale of a cow. A romance blossomed between the two.

Speaking at the Library in 1998, their son, the author Philip C. Bobbitt, provided some background on his parents’ courtship, which culminated with their marriage in 1941.

“I discovered a cache of old index cards, apparently used as surreptitious notes passed by my parents to each other under the eyes of a superintendent who supposed, perhaps, that Mother was typing Dewey decimals. … On each was typed an excerpt from a poem. The long campaign by which my father moved from conspiratorial co-worker to confidant to suitor was partly played out in the indexing department of the Library.”

Following her death in 1978 at age 68, her husband and son decided to endow a memorial in her honor.

“Owing to the history I have described,” Bobbitt added, “the Library of Congress was suggested as a possible recipient of this memoriam.”

Thus, the Rebekah Johnson Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry was established at the Library in 1988, and awarded biennially since 1990. The $10,000 prize recognizes the most distinguished book of poetry written by an American and published during the preceding two years, or the lifetime achievement of an American poet. Charles Wright, the current Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry, was awarded the Bobbitt Prize for lifetime achievement in 2008. Poet Patricia Smith recently received the 2014 Bobbitt Prize for her work, “Shoulda Been Jimi Savannah.” (She will receive the award and read selections from her work at the Library on April 6.)

“The Bobbitt family’s relation to the Library is a great love story and it is too good not to want to savor, commemorate and celebrate,” said Librarian of Congress James H. Billington.

March 31, 2015

Celebrating Women’s History: America’s First Female P.I.

Allan Pinkerton. 1884. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Walking into the Chicago office of Allan Pinkerton’s detective agency one afternoon in 1856 was a woman of medium height, “slender, graceful in her movements, and perfectly self-possessed in her manner.” Claiming to be a widow, aged 23, Kate Warne was looking for a job, and not as a secretary. One could imagine Pinkerton’s surprise at such a request – women just weren’t employed for such things. Needless to say, Pinkerton decided to give Warne a chance. Perhaps it was her dark blue eyes “filled with fire” and the quiet strength and compassion she radiated that tipped the scales in her favor.

Hiring Warne would turn out to be one of the best decisions Pinkerton ever made. She became the first female detective in the United States and would become the superintendent of the female bureau of the Chicago office.

“In my service you will serve your country better than on the field. I have several female operatives. If you agree to come aboard you will go in training with the head of my female detectives, Kate Warne. She has never let me down,” Pinkerton once said.

Warne offered a skill set that Pinkerton’s male agents didn’t have – the ability to gain the confidence and friendship of other women for the purpose of gaining valuable information related the agency’s criminal cases.

According to author Daniel Stashower, Warne proved herself to be fearless and versatile. In one investigation, she posed as a fortune-teller to entice secrets from a suspect. In another, she made friends with the wife of a suspected murderer.

Warne played an integral part in several high-profile cases. Early on in her career, she was brought on board the case of the Adams Express Company – the detective agency was investigating the theft of several thousand dollars from the railroad company. Pinkerton had a hunch the money was stolen by a man named Nathan Maroney, the manager of the Adams Express office in Montgomery, Ala., and the last person to have possession of the locked pouch the money had been kept in. Pinkerton sent Warne in to befriend Maroney’s wife in hopes that she would divulge the truth of her husband’s actions. And that she did, taking Warne to the location where the money was hidden and thus solidifying the evidence and case against Maroney.

Pinkerton wrote, “The victory was complete, but her [Warne] faculties had been strained to the utmost in accomplishing it, and she felt completely exhausted. She had the proud satisfaction of knowing that to a woman belonged the honors of the day.”

Warne would prove herself yet again valuable in what was probably the defining case of her career. In 1861, Pinkerton foiled an attempt to assassinate newly elected President Abraham Lincoln while on a whistle-stop train trip to Washington, D.C., for his inauguration. While investigating robberies on the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad, Pinkerton uncovered the plot. He sent Warne to Baltimore as a spy to infiltrate the southern sympathizers. Posing as a Mrs. Barley, a visitor from Alabama, Warne’s job was to “cultivate the wives and daughters of suspected plotters.” The attempt on the president-elect’s life would be made while he was passing through the city.

Adalbert John Volck. Passage through Baltimore from V. Blada’s “War Sketches.” Baltimore: 1864. Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

“Mrs. Warne was eminently fitted for this task. Of rather a commanding person, with clear-cut, expressive features, and with an ease of manner that was quite captivating at times, she was calculated to make a favorable impression at once,” Pinkerton wrote in his book, “The Spy of the Rebellion.” “She was of Northern birth, but in order to vouch for her Southern opinions, she represented herself as from Montgomery, Alabama, a locality with which she was perfectly familiar, from her connection with the detection of the robbery of the Adams Express Company, at that place.

“Mrs. Warne displayed upon her breast, as did many of the ladies of Baltimore, the black and white cockade, which had been temporarily adopted as the emblem of secession, and many hints were dropped in her presence which found their way to my ears, and were of great benefit to me.”

Warne’s involvement went even further. Not only did she courier messages to Lincoln’s party, but she also helped smuggle the president himself onto a train that would ultimately pass through Baltimore with him undetected.

Stashower’s book “The Hour of Peril” chronicles the case, including Warne’s involvement. For his book, Stashower conducted research at the Library, using the Records of the Pinkerton’s National Dectective Agency and the papers of Abraham Lincoln and John G. Nicolay.

In this video, Stashower discusses his book and Warne’s involvement in foiling the “Baltimore Plot.”

{mediaObjectId:'FB30AC5B2ECC0666E0438C93F0280666',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

Warne continued on in Pinkerton’s employ until 1868, when she fell ill and died. She is buried in the Pinkerton family plot in Graceland Cemetery in Chicago.

The Library’s Pinterkton Detective Agency collection doesn’t contain many references to Warne. Of particular note is a pamphlet, written by Pinkerton, of the events in 1861. It was written in response to a published letter by John A. Kennedy, who claimed, along with his detective force, the responsibility of discovering the plot. In the pamphlet are references to Warne corroborating her involvement in the Baltimore plot.

Most of the Pinkerton’s Chicago office files were destroyed in a fire in 1871, so beyond Pinkerton’s published writings, little more is known of the female detective. Warne was certainly an intriguing figure, and perhaps little documentation exists because she was a good spy!

This obituary of sorts in the March 19, 1868, issue of the Democratic Enquirer (Ohio), recounts news of Warne’s exploits while at the Pinkerton agency.

“Up to the time of her death, her whole life had been devoted to the service into which she had entered in her younger years. She was undoubtedly the best female detective in America, if not the world.”

Sources: Daniel Stashower, “The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War” (St. Martin’s Press, 2013); www.pinkerton.com; Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency records, 1853-1999, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

March 27, 2015

“Make Speedy Payment”: Women, Business and George Washington

(The following is a guest blog post by Julie Miller, early American historian in the Manuscript Division.)

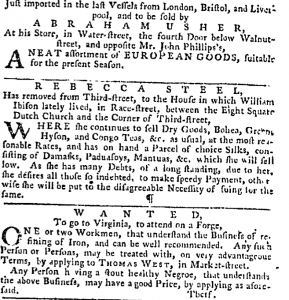

Rebecca Steel, advertisement, Pennsylvania Gazette, Oct. 9, 1766.

In 1766, Philadelphia shopkeeper Rebecca Steel advertised that she had for sale “Dry Goods, Bohea, Green, Hyson, and Congo Teas &c. as usual, at the most reasonable Rates,” and also “a Parcel of fine silks” that she would “sell low” (Pennsylvania Gazette, Oct. 9, 1766). In the same advertisement she warned her customers that if they didn’t “make speedy payment,” she would “be put to the disagreeable Necessity of suing.” A decade later, in the thick of the Revolutionary War, George Washington bought tea from Steel. He didn’t have to worry about being sued, however, since he paid his bill. We know this because the receipt, () signed by Thomas Mifflin, quartermaster general of the Continental Army, is in his papers at the Library of Congress.

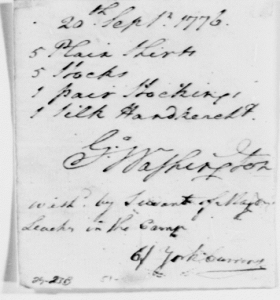

Steel’s receipt is just one among many pieces of evidence in Washington’s papers that he regularly did business with women. Many of the women he dealt with were poorer and less formidable than Rebecca Steel. In New York on Sept. 20, 1776, he paid a woman six shillings to wash his “plain shirts,” stocks (a kind of 18th-century necktie), stockings and a silk handkerchief. The he signed identifies her only as a “servant of Major Leach in the camp.” (See this story from the Teaching with the Library of Congress blog about another laundress who worked for Washington during the Revolutionary War.) Hannah Till, a servant who worked at Washington’s headquarters at Morristown, N.J., signed the for wages she received on June 23, 1780, with an X, the mark used in place of a signature by people who did not know how to write. These were temporary jobs for poor women with limited skills who were available to work for Washington as he moved around from place to place during the Revolutionary War.

Bill for Tea, Feb. 10, 1777, signed by Thomas Mifflin and James Steel for Rebecca Steel. Rebecca Steel’s husband James had been dead since 1742, so this James may have been a son or other relative. George Washington Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

Other women had more sophisticated skills or valuable goods to offer. Dorothy Shewcraft, for example, sold Washington a pair of andirons and a “scotch carpett” for his New York headquarters (), and Hannah Stewart made him “table cloths and two towels” when he was headquartered in West Point (). Both Shewcraft and Stewart signed the receipts they received from Washington with clear, neat signatures. Widow Ann Emerson, housekeeper in Washington’s Philadelphia household while he was president, came so highly recommended that she felt confident enough to bargain for her salary, declining to accept less than £50 per year, a price, Washington’s secretary reported, that was “much too high.” Emerson also won the privilege of keeping her 7-year-old daughter with her, even though Martha Washington “had rather it should not be brought into the family.” This was a standard objection on the part of employers of live-in servants. ().

Much of the work that women did for pay in early America was an extension of household work. Women kept gardens and sold produce, kept chickens and sold eggs, and kept cows and sold dairy products. Young, unmarried women often went to work as servants for their neighbors as a way to experience a little independence and build a nest egg before marriage. Nearly all women were constantly at work spinning, weaving, sewing, knitting, mending and washing. Women delivered babies and provided nursing for their families and neighbors. In a world in which there were no grocery stores, clothing stores and sometimes, especially on the frontier, no trained doctors, these women provided not only for their households but also for their communities.

Some women, however, stepped into traditionally male domains, operating printshops and publishing newspapers, managing land, farming, and owning shops, merchant and manufacturing firms, and trading ships. Typically these women were widows. According to Anglo-American law in this period, when a woman married, her husband took control of her property and the money she earned legally belonged to him. When a woman’s husband died, however, she could regain her economic autonomy and in some cases get control of family property and businesses. Some wives had been supporting their husbands’ businesses with their money or labor long before they owned them as widows.

Washington dealt with several such widows. From the 1760s through the early 1770s, when in accord with revolutionary boycotts he stopped importing goods from England, he repeatedly bought nails, hinges, padlocks and other metal supplies from the British firm of Theodosia Crowley and Co. Crowley was in her 30s when her husband, heir to one of England’s great ironworks, died and left her the business until her sons were old enough to take over. They lived long enough to do so, but when they too died young, Crowley took over the business again and ran it herself with the help of a series of managers. By the time she died at 88 in 1782, she had run the business for a total of 38 years. Not only had she outlived her husband by more than half a century, she also outlived all six of her children. (For Washington’s purchases from Crowley, see, for example, Robert Cary, invoices,, or ).

During the revolution, Washington dealt not only with Rebecca Steel, the Philadelphia tea merchant, but also with Ann Van Horne, a New York wine merchant. In April 1776, just before Washington arrived in New York City to face the British ships that were gathering threateningly in the harbor, the steward and housekeeper in charge of setting up his headquarters ordered 37 bottles of wine from Van Horne. Unlike Hannah Till, who could not sign her name, in a clear, firm hand. Van Horne had married into a family of New York merchants, one of whom was her husband, Garrit Van Horne, who had died by 1765. He seems to have respected her business abilities, since he made her a co-executor of his will. Advertisements in New York newspapers in the 1760s and 1770s show her managing his estate, selling Madeira, claret, brandy, sugar and Cheshire cheese, and also substantial land holdings and a slave. (New York Mercury, Sept. 23, 1765; New York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury, Aug. 12, 1771).

Receipt signed by George Washington for laundry done by a “servant of Major Leach in the Camp,” New York, Sept. 20, 1776. George Washington Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

The following winter Washington purchased tea from Rebecca Steel. Like Ann Van Horne, Steel was a widow and the co-executor of the estate of her husband, James Steel (Pennsylvania Gazette, Dec. 2, 1742). Historian Karin Wulf identifies her as one of Philadelphia’s handful of “elite” women shopkeepers. One of her frequent customers was Quaker Philadelphian Catherine Drinker, whose detailed diary records her visits to Steel’s shop and her husband Henry Drinker’s attendance at her funeral in 1783. Steel’s life can also be traced in her advertisements in Philadelphia newspapers.

More long-lasting and complex was Washington’s business relationship with his Virginia neighbor, Penelope Manley French. French was a wealthy widow of Washington’s own age who owned land adjacent to Washington’s that he very much wanted to buy but that she did not want to sell. Her ownership of the land took the form of a life interest that would pass to her only child, Elizabeth, at her death. When Elizabeth married in 1773, two years after the death of her father, Daniel French, Washington commented: “Our celebrated Fortune, [Miss] French, whom half the world was in pursuit of, bestowd her hand on Wednesday last . . .” (Washington to Burwell Bassett, Feb. 15, 1773). Penelope French’s land formed a part of the fortune that Elizabeth French brought to her husband, Benjamin Dulany. (The Virginia Gazette in Williamsburg, which contained the Dulanys’ marriage announcement, was published by widow Clementina Rind. The following year, Virginia’s House of Burgesses, of which Washington was a member, appointed her the colony’s printer).

French held out against Washington for many years. But despite her display of determination, there is not a single letter between her and Washington in his papers. All her communication with him was carried out through male surrogates, her son-in-law and her half-brother, William Triplett. Eventually she gave in – partially. In 1786 Penelope French agreed, not to an outright sale, but to a rental of the land for the duration of her lifetime. But even after she agreed to it, French didn’t make it easy for Washington to conclude the deal. When in September 1786 Washington rode over to William Triplett’s to meet with French and sign the papers, he found Triplett sick in bed and French absent. He and Triplett signed the papers a month later in court in Alexandria, without her ().

Washington continued to work around French. In a 1799 letter to Benjamin Dulany about a related arrangement (Washington to Benjamin Dulany, July 15, 1799) in which he was renting slaves from French, Washington carefully writes, “I thought it respectful & proper however, to couple her name with yours” and acknowledges Dulany’s own interest in the deal, since the slaves would “ultimately, descend to you, or yours.” (Washington to Benjamin Dulany, Sept. 12, 1799.) Washington was treading difficult territory here. On one hand he scrupulously named French, who was after all the one he was doing business with; at the same time he reminded her son-in-law, who was acting for her, of his own stake in the deal. (The slaves who were the subject of the deal had no say at all.) Washington died that December; Penelope French outlived both him, and the arrangement she made with him, by almost six years (Penelope French obituary, Alexandria Advertiser, Oct. 19, 1805).

Invoice for nails, files, knives, locks, hinges, and other goods purchased by George Washington from Theodosia Crowley and Co., March 1761. George Washington Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

Washington’s papers are full of evidence that he was willing to make business deals with women. What went wrong in his negotiations with Penelope French? It appears that she was unwilling to deal directly with him. Maybe the clash between the unworldly gentility expected of white southern ladies and her status as a substantial landowner made her uncomfortable in a way that the illiterate servant Hannah Till simply could not afford to be. Their stories are just a few samples among many in Washington’s papers of a side of Washington worth thinking about during Women’s History Month.

Read More About It

George Washington’s papers are in the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress, and you can see them online. The published edition (which currently does not include most of Washington’s financial papers, including these bills) is at Founders Online.

Newspaper advertisements are a wonderful way to learn about women in business in early America. You can find out about them at the Library of Congress Newspaper and Current Periodical Reading Room.

I learned about Theodosia Crowley in: M.W. Flinn, “Men of Iron: The Crowleys in the Early Iron Industry” (Edinburgh University Press, 1962). Rebecca Steel: Karin Wulf, “Not All Wives: Women of Colonial Philadelphia” (Cornell University Press, 2000) and “The Diary of Elizabeth Drinker” ed. Elaine Forman Crane (Northeastern University Press, 1991, 3 vols.). Ann Van Horne: Jean P. Jordan, “Women Merchants in Colonial New York,” New York History 58 (October 1977): pgs. 412-439 and the papers of Levinus Clarkson, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. There appears to have been more than one Ann Van Horne. An Ann Van Horne died in 1773 (see a notice concerning her estate in Rivington’s New York Gazetteer, May 6,1773), three years before another Ann Van Horne signed Washington’s receipt for a wine purchase.

For some background on women, work and the law in early America see: Laurel Thatcher Ulrich: “Good Wives: Image and Reality in the Lives of Women in Northern New England, 1650-1750″ (Alfred A. Knopf, 1982) and “A Midwives Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on her Diary, 1785-1812″ (Alfred A. Knopf, 1990); Marylynn Salmon, “Women and the Law of Property in Early America” (University of North Carolina Press, 1986); and Linda Kerber, “Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America” (University of North Carolina Press, 1980).

March 26, 2015

Curator’s Picks: American Women Poets

The following is an article from the March/April 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, in celebration of both Women’s History Month (March) and National Poetry Month (April). The issue can be downloaded in its entirety here.

American history specialist Rosemary Fry Plakas highlights several women poets whose works are represented in the Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

British-born Anne Bradstreet (1613-1672) was the first woman poet to be published in colonial America. Her poems were first published in London in 1650, followed by an expanded edition published posthumously in Boston in 1678. “Both in her breadth of subjects–home, family, nature, history, philosophy and religion–and in her sensitivity to prejudices against women’s writings, Bradstreet is a worthy pathfinder for the women who have followed her.”

“The Tenth Muse lately Sprung up in America,” London, 1650

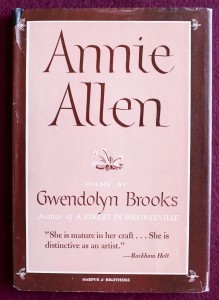

In 1950, Gwendolyn Brooks (1917-2000) became the first African American to receive the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. “In her prize- winning work ‘Annie Allen,’ Brooks provides a poignant portrait of a young black girl in Chicago as a daughter, wife and mother.” After many productive years of writing and teaching, Brooks became the first African American woman to serve as the Library’s Consultant in Poetry, 1985-1986.

“Annie Allen,” New York, 1949

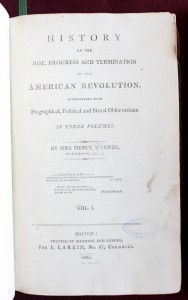

Poet and dramatist Mercy Otis Warren (1728-1814) drew on her literary talents, democratic convictions and friendships with patriot leaders to produce her three-volume commentary on the American Revolution. “This singed title page of Thomas Jefferson’s personal copy shows how close it came to the flames of the Christmas Eve 1851 fire that destroyed nearly two thirds of the books Jefferson had sold to Congress in 1815.”

“History of the Rise, Progress and Termination of the American Revolution,” Boston, 1805

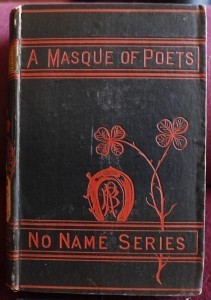

Emily Dickinson’s (1830- 1886) beloved poem “Success”– one of the few published during her lifetime–was submitted without her permission by childhood friend and fellow poet Helen Hunt Jackson (1830-1885). “Jackson urged Dickinson relentlessly to publish her poems and wished to be her literary executor, but alas, Jackson died the year before Dickinson.”

[George Parsons Lathrop] editor, “A Masque of Poets,” No Name Series [v. 13] Boston, 1878

African-born poet Phillis Wheatley (1753-1784) was a slave educated by her Boston owner’s wife, who encouraged her to publish her poems. This collected work was published by the Countess of Huntingdon in London, where Wheatley had been welcomed by Benjamin Franklin and abolitionists Grenville Sharpe and the Earl of Dartmouth. “Her portrait was probably drawn by the African American artist Scipio Moorhead, whose creative talents are praised in one of Wheatley’s poems.”

“Poems on Various Subjects: Religious and Moral,” London, 1773

*All images | Rare Book and Special Collections Division

March 25, 2015

BOOM Shaka-laka-laka!

Where were you when you first heard that?

“Stand!” by Sly and the Family Stone

I was in the theater audience for the movie “Woodstock,” and I recall thinking even then that the section featuring Sly and the Family Stone was the high point of the film. Now, whenever I hear “I Want to Take You Higher,” which has the Boom-shaka-laka-laka bridge between verses, I visualize the long fringe, on Sly Stone’s jacket sleeves, flying through the air in slow motion.

The 1969 long-playing album “Stand!” by Sly and the Family Stone, which includes that song, not to mention the hit “Everyday People” and the title cut, is among 25 recordings being added to the Library of Congress National Recording Registry for 2014. This designation is given to recordings regarded as having cultural, artistic or historical significance worthy of preservation for future generations.

This year’s recording registry additions (bringing the grand total of recordings so designated to 425) are a lively mix of rock, folk, pop, jazz, blues, religious and classical, some spoken-word, and some historic recordings.

For example, there’s “Sixteen Tons” by Tennessee Ernie Ford, who had a huge hit in 1955 with this song about a tough hombre who mines coal for a living: “You load 16 tons and what do you get? Another day older, and deeper in debt. Saint Peter, don’t you call me ’cause I can’t go – I owe my soul to the company store.”

Ford, a popular bass-baritone, managed to put a lot of grit into his performance of the song even when he sang it with crystal-clear enunciation (he had classical voice training), wearing a tailored suit.

But to add true grit, this year’s recording registry also includes Blind Lemon Perkins’ 1928 recording of “Black Snake Moan” and “Match Box Blues.”

Joan Baez Photo by William Claxton

Joan Baez’s first album recorded in 1960 and titled with her name is in this year’s registry. It is a collection of folksongs, sung in her bell-like voice with minimal accompaniment, committed to vinyl at the dawn of her long and productive career.

Also on this year’s list is jazz saxophonist Gerry Mulligan’s 1953 live concert version of “My Funny Valentine.” The Gerry Mulligan collection is held at the Library.

Lauryn Hill’s 1998 “The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill” is on this year’s list, along with Radiohead’s 1997 album “OK Computer.” Ben E. King’s soulful “Stand By Me” (1961) is listed, along with the Righteous Brothers’ painful “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin'” from 1964.

The Doors’ eponymous first album (1967) is there, too – which includes not only the high-airplay “Light My Fire” and the highly regarded album cut “The End” but also their version of Kurt Weill’s wry, dry “Alabama Song,” better known by its lyric “Oh, show me/ the way/ to the next/ whiskey bar – No, don’t ask why.”

Touching base with history, there is a set of wax-cylinder recordings of sounds people captured at home between 1890 and 1910, collected by the University of California, Santa Barbara Library; radio coverage of the funeral of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, featuring a sobbing breakdown on the air by reporter Arthur Godfrey; 101 wax-cylinder recordings made of international displays presented at the 1893 World’s Fair at Chicago; and two Irish fiddle tunes laid down in 1922 by Michael Coleman, a violinist who kept this element of Eire real, both in his home nation and in the U.S.

Meanwhile, on the lighter side, the registry takes in Steve Martin’s 1978 LP of wacky bits from two standup shows, titled “A Wild And Crazy Guy” and an album that gathered together some of the best-loved songs from the show “Sesame Street.”

And in a nod to the rise of women in classical music, the 2014 registry includes “Fanfares for the Uncommon Woman,” recorded by the Colorado Symphony conducted by Marin Alsop. The 1999 album presents five fanfares written by composer Joan Tower celebrating “women who are adventurous and take risks” with each fanfare dedicated to a different woman of the music world. It is appropriate that the Colorado Symphony recorded this collection, in that Colorado was an early adapter to women on the concert-hall podium – not only Alsop but also Antonia Brico and JoAnn Falletta.

March 23, 2015

Wipe That Scowl Off Your Face

Photography was well-established by the dawn of the 20th Century–it had graduated from the tintype and daguerreotype to innovations allowing for smaller cameras and more portable exposure media. But as the 1800s became the 1900s, portrait photography carried forward a tradition of depicting people sitting stiffly, staring sternly into the camera.

A handsome young immigrant from Germany, who came to San Francisco as the employee of family friends from back home and fell in love with the city by the bay, changed all that. His name was Arnold Genthe, and his papers (including numerous photographs) are in the collections of the Library of Congress.

Photographer Arnold Genthe, in his youth

Genthe had a classical European education–his father had been a professor–and early in life Arnold hoped to be an artist. But after his father’s death, the family struggled to cover costs, and his mother’s artist cousin frankly counseled him to relegate art to his leisure hours and find something more lucrative as a living. When Arnold went to San Francisco in 1895 (temporarily, he thought) it was as the tutor of the young son of wealthy family friends.

In his 1936 biography, “As I Remember,” Genthe described how fascinating he found all the worlds-within-worlds within San Francisco. He was advised to avoid the city’s Chinatown, a warning that only drew him in. In a bid to capture some sense of that unique place, he hit upon using photography:

“When I looked for pictures to illustrate my letters, there were none to be had except a few inadequate crudely colored postal cards. I tried to make some sketches. As soon as I got out my sketchbook the men, women and children scampered in a panic into doorways or down into cellars. Finding it impossible to get pictures in this way, I decided to try to take some photographs. Up to that time I had never used a camera … it had to be small enough to carry in my pocket, as I had learned that the inhabitants of Chinatown had a deep-seated superstition about having their pictures taken.”

Over a period of months, he successfully took numerous photos in Chinatown, which later became a book you can read on the Internet Archive: “Old Chinatown” published in 1913. He joined a photographers’ club, and eventually decided to become a portrait photographer capable of capturing lively, candid photos.

Genthe, who was fortunate to have as clients many well-to-do locals who recommended him to others, eventually was in demand on the East Coast as well to photograph not only wealthy individuals (John D. Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan) and political leaders (Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson), but also artistic endeavors – theater, film and dance (Greta Garbo, Sarah Bernhardt, Isadora Duncan) and portraits of authors (Jack London, Ida Tarbell) and poets (William Butler Yeats and Edna St. Vincent Millay). (Her papers are at the Library).

Genthe is also immortalized as one of the most articulate eyewitnesses, with photos to back his words, of the great San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906:

“One scene that I recorded the morning of the first day of the fire … shows … a house, the front of which had collapsed into the street. The occupants are sitting on chairs calmly watching the approach of the fire … When the fire crept up close, they would just move up a block.”

Approaching fire during the Great San Francisco Earthquake

Genthe lost nearly everything he owned that week except the clothes on his back and the camera in his hand (the negatives for his Chinatown book were stored outside San Francisco, so they survived), and he moved to New York, where his career flourished. He died of a heart attack in 1942, famous as one of the world’s most accomplished photographers. The Library purchased the photos remaining in his studio at the time of his death.

March 17, 2015

Celebrating Women: Women’s History on Pinterest

(The following blog post is by Jennifer Harbster, a science research specialist and blogger for the Library’s Science, Technology, and Busines blog, “Inside Adams.” Harbster also helped create the Library of Congress Women’s History Month board on Pinterest.)

Alison Turnbull Hopkins at the White House on New Jersey Day. Jan. 30, 1917. Library of Congress Manuscript Division.

March is designated as Women’s History Month and this year the National Women’s History Project has selected “Weaving the Stories of Women’s Lives” as the theme. To help commemorate Women’s History Month, the Library has created a Pinterest Board that offers a visual celebration of the diverse stories of women in the United States.

Images capture moments in time and connect us to history; they awaken our senses, revive memories and inspire us. With the Library’s extensive collections related to women’s history, there is an array of material to showcase. We have pinned images from a broad range of women’s achievements, including politics, civil rights, sports, medicine, science, industry, arts, literature, education and religion.

There are images that focus on the stories of the women’s suffrage movement in the U.S. We “pinned” images from the Library’s Women of Protest Photographs from Records of the National Women’s Party, such as the “‘Silent Sentinel’ Alison Turnbull Hopkins at the White House” (1917), who carries a sign that reads “Mr. President, How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty.”

Maude Younger. Between 1909 and 1932. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

We also pinned memorabilia and images from the Miller National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) Suffrage Scrapbooks, 1897-1911 collection. The women suffragist images are powerful and portray the strength of the modern woman. One of my favorites is from the early 20th century of Miss Maude Younger, legislative secretary of the National Woman’s Party, working on her car in the streets of Washington, D.C.

The Women’s History Board also tells the stories of women who stepped into the workforce during World Wars I and II. The Farm and Security Administration Office of War Information (FSA/OWI) Photograph Collection (color and B/W prints) brings to our attention the spirit and determination of women who worked jobs normally dominated by men in the defense plants, railways and farms. The photographer Ann Rosener, who worked for the FSA/OWI, documents the changing roles of women. We pinned a couple of her images of women on farms – one is a woman behind the wheel of a tractor and the other is a group of women harvesting asparagus in Illinois.

Women in war: agricultural workers. Photo by Anne Rosener, Sept. 1942. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

This board also offers up a medley of images of women who drove race cars, flew airplanes, rode motorcycles and played golf. Throughout the month of March, we will be adding more images, so follow us to keep up with the new pins.

We hope the Women’s History Pinterest Board will inspire you to learn more about the individual story of a woman or the larger narrative of that moment in history from the perspective of a woman.

If you’d like to learn more about the Library’s Women’s History collection, a good place to start is American Women: Gateway to the Library of Congress Resources Related to the Study of Women’s History and Culture in the United States.

Several of the other Library blogs are featuring content in celebration of Women’s History Month.

Inside Adams: “Marie Curie: A Gift of Radium”

In Custodia Legis: “Women in History: Lawyers and Judges,” “Women in History: Elected Representatives” and “Women in History: Voting Rights”

Teaching with the Library of Congress: March in History

March 12, 2015

Wild Irish Foes

Today we’re going to add a new term to your broad vocabulary: Fenian. It’s a noun that describes a member of an Irish or Irish-American brotherhood dedicated to freeing Ireland from British dominion. The name was taken from the “Fianna,” a group of kings’ guards led by the legendary Irish leader of yore, Finn MacCool.

Bet you didn’t know that in 1866, large numbers of Irishmen (back in Ireland) and Irish-American men mustered out of service in the Civil War staged military-style actions in the name of their Fenianism, including a couple of attacks on Canada. (t was one of a handful of episodes in history of arms being taken up from within the U.S. against our northern neighbor – more on that shortly). The idea was to draw out the British military to focus on the Canadian trouble (Canada, at that time, being a British colony), making it easier for the Irish rebels to seize power back in Ireland and declare it a separate, self-governed nation.

The Battle of Ridgeway, Ontario

In April, hordes of Fenians massed in northern Maine, with the intent of seizing Campobello Island, part of British Canada. Both English and U.S. warships were positioned in the waters off the coast to tamp down the Campo-bellicosities. The governor of Maine asked for permission to call out the National Guard of the era, to help keep the peace.

Later that year, in June, an estimated 1,000 Fenians made a move across the U.S. border north to the outskirts of the Canadian town of Ridgeway, Ontario, on the northern shore of Lake Erie. There, they skirmished with Canadian troops, killing outright nine Canadian riflemen, according to Battle of Ridgeway expert Peter Vronsky, with more than 20 other Canadian deaths from battle injuries later; the Fenians lost up to six of their number on the spot with several later casualties. The Canadians captured scores of Fenian combatants, and later tried many, according to David Bertuca. After another fight in the area the Fenians re-crossed into the U.S., where many Fenians were arrested. Then-President Andrew Johnson publicly declared that the U.S. had no hostile intentions toward the Canadians. One other Fenian raid attempt on Canada was made in 1870; it, too, was abortive.

These imbroglios were all over the newspapers, even then. Here is one of those newspapers from 1866 you can read on the Library of Congress/National Endowment for the Humanities site, “Chronicling America.” And here is another account of the Fenian attacks.

The Fenians had songs they sang to raise morale at their meetings and various other propaganda.

Lest their activities seem merely rowdy, keep in mind that this was only 20 years after the first starvation deaths occurred in the Great Irish Famine. That unspeakable human tragedy killed at least a million people and caused twice that number to flee Ireland; many went to the United States. British policies, many historians say, exacerbated the suffering of the starving Irish and contributed to the high mortality of the famine, which was triggered by a potato blight that wiped out the sustenance crop virtually overnight.

You’ll still hear songs about the Fenian men sung in Irish pubs from Dublin to Dingle and from New York to San Francisco.

What were the other U.S. sorties against the Canadians? Well, the U.S. did torch Toronto (then known as York) in the War of 1812, which some say spurred the Brits to get even by burning Washington (an event that led to a new-and-improved Library of Congress).

The other was a border dispute on San Juan Island, northwest of Seattle and south of Vancouver. Known as the “Pig and Potato War,” two nationals of the respective nations got into a tiff over a Canadian porker that ransacked a Yankee’s tuber patch. Nobody died, but the British and Americans built military camps on San Juan Island that you can still visit today.

March 10, 2015

George Washington and the Weaving of American History

(The following is a guest post by Julie Miller, early American history specialist in the Manuscript Division.)

What stories can that George Washington assembled to track the productivity of his weaving workshop at Mount Vernon tell? The book, which is part of the extensive collection of financial records that are part of Washington’s papers at the Library of Congress, doesn’t look like much. Nine inches high and seven-and-a-half pages wide, it was rebound by Library conservators very simply in paper, having at some point lost its original binding, if it ever had one. Its 26 pages contain a series of tables, neatly drawn by Washington himself, each with the heading “An Account of Weaving Done by Thomas Davis &c in the Year . . . ” These describe the output of the weaving workshop from January 1767 to January 1771, show how much of what the weavers made Washington used himself and how much he sold to his neighbors, and tell less than we would like to know about the free and enslaved weavers who worked there.

Patterns for Ms and Os and Birdeye in John Hargrove, “The Weavers Draft Book and Clothiers Assistant” (Baltimore, 1792). Reprinted in 1979 by the American Antiquarian Society, edited by Rita J. Adrosko.

One story is about Thomas Davis, the weaver who ran the workshop. Skilled weavers were scarce in colonial America, and Washington probably hired Davis from England. The workshop’s output, as documented in Washington’s neat hand, is a testament to the range of Davis’s skills and knowledge. Washington carefully recorded the weight (of the thread before it was woven and then of the finished cloth), width, density (in a column headed “hundreds in the width,” referring to the loom’s warp threads), and length of each piece; how long it took to weave, its price per yard and what type of cloth it was. At intervals, he added up what the weaving workshop had earned.

Davis and the weavers under his supervision worked in cotton, wool, linen and silk. They produced a variety of weaves, patterns and types of fabric, including bird eye, in cotton and wool; cotton and wool plaids; a pattern called Ms and Os; cotton striped with silk; linsey-woolsey, a mix of linen and wool; fustian, a rough cloth of cotton and linen; shalloon, a woollen material used for linings; and jean, sometimes spelled “jane,” a thick, twilled cotton that only later was associated with the blue jeans we wear today. The name of another fabric the weavers produced, diaper, also had yet to take on its modern meaning. They also turned out fish nets, harness, carpets, counterpanes and coverlets, and bed ticking. (Given the detail in which Washington recorded this information, it is interesting that he never mentioned color.)

“What Kind of Cloth,” 1770, showing Ms and Os, “Janes,” striped silk and cotton, carpet and more. George Washington Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

Davis may have been at Mount Vernon as early as 1766, before the book begins, and he was still there in 1773, so Washington must have been satisfied with him. Davis, however, may not have been so happy. Washington notes that in July and August of 1767 Davis had two bouts of sickness, and his farm manager reported that during this time he had fits in which he lay so long that he appeared to be dead (Lund Washington to George Washington, Aug. 17, 1767). Davis was also lonely. In 1773 Washington responded to Davis’s “particular request & earnest entreaty” to bring his mother and sister to join him, recording in a that he paid a ship captain for their passage.

What about the weavers Davis supervised? The only other weavers named in the book are slaves identified by Washington as Dick and George. References to them appear in the column headed “Sickness with other Remarks & Occur[rences]” that Washington used to record information about the weavers. The notation “wove by Dick” appears in this column twice, both times in July 1767, when he wove a total of 65-and-a-half yards of linen. George, who is mentioned more often, appears in 1769 and 1770 weaving linen, a mixture of cotton and wool, and a fabric called kersey. In January and February 1770, Washington noted that George, evidently a profitable worker, missed a total of 20 days of work, partly due to sickness, partly because he was working elsewhere.

In the last pages of the book Washington notes another set of workers: “one white woman” and “5 Negro Girls” – spinners. Washington’s identification of these women as “white” and “Negro” is his shorthand for free and slave. He hired the white woman, but the girls of African descent were probably slaves. Spinning, the process by which fluffs of raw fiber were twisted and counter-twisted with a hand-held spindle or spinning wheel into strong, smooth lengths of thread for weaving, was so ubiquitous a female activity that the word “spinster” was also used to mean an unmarried woman.

Spinning was a woman’s job, but weaving, especially in Britain and continental Europe, was a job typically held by men. Weavers were skilled craftsmen who had been trained in apprenticeships and formed guilds, trade unions and other associations to protect their craft. As a group they occasionally rose up to protect their rights. In the second half of the 1760s, just as Washington was documenting the work of his Mount Vernon weavers, the silk weavers of Spitalfields in London staged a series of uprisings to protest undercutting of their prices. In one such protest a crowd of hundreds of weavers descended on a colleague they believed was “working under price,” cut the work out of his loom, set him backwards on an ass and rode him through the town, “hooting, hallowing, and making a great uproar.” (Pennsylvania Chronicle, and Universal Advertiser, Sept. 11, 1769.) This was the same sort of ritualized violence, rooted in British tradition, that the American revolutionaries were soon to visit on the loyalists in their midst.

At Mount Vernon, the enslaved weavers and spinners and the ill and isolated Davis had little opportunity to follow the example of the Spitalfields weavers and assert their rights. But George Washington did. In the 1760s, the Anglo-American colonists were becoming annoyed by what they felt were unjust taxes, such as those imposed by the Stamp Act of 1765 and the Townshend Act of 1767, and other British impositions that the Continental Congress would later list in the Declaration of Independence. In 1769, Virginia, like other American colonies, began boycotting British goods. George Washington, a member of Virginia’s legislature, the House of Burgesses, supported the boycott (see his , April 5, 1769, click here for a transcription). In this period Washington was also looking for ways to diversify the production of his Virginia estate. At the end of the 18th century, tobacco, which had been so valuable to the earliest Virginia settlers, was declining as a profitable crop. Like other Virginia planters, Washington began to rely more on crops such as wheat and flax, and sources of income such as milling and fishing. The weaving workshop — which made linen out of his flax, nets to catch his fish and cloth to supply his estate and sell to his neighbors — was part of that effort.

“Wove by Dick,” 1767. George Washington Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

For years, Washington had been buying textiles, along with other goods, from London merchants in exchange for his tobacco. Now he was reconsidering that practice on both financial and political grounds. On the last pages of the book are notes that show him calculating what it cost him to manufacture textiles at home compared to the cost of importing them from Britain. Or as he put it (with the creative capitalization, spelling and punctuation of the 18th century): “A Comparison drawn between Manufacturing, & importing; the goods on the otherside.”

Washington’s realization, in the 1760s, about the connection between manufacturing and national autonomy appears to be the story George Washington created this book to tell. He had hired weavers before 1767 and continued to do so after 1771, but it was only during this period of political and economic turbulence that he chose to create a separate record of his Mount Vernon weaving business and to calculate exactly what it earned and what it cost him. After he became the first president of the United States, domestic manufacturing became central to the program advocated by his treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton, and by Washington himself.

In the fall of 1789, soon after he became president, Washington went on a tour of the New England states. In Boston he visited a “duck manufacture,” a workshop that wove duck, a sturdy cotton fabric. Proto-factories like this one were forerunners of the steam and water-powered factories that would appear in New England in greater numbers in the decades to come. Once again Washington paid close attention to the details, counting 28 looms and 14 spinners, mainly girls and women from local farming families who were paid for their labor. The workers, he remarked in his diary (), “are the daughters of decayed families, and are girls of Character – none others are admitted.” He did not dwell on the similarity between their predicament – worn-out farms (this is the “decay” he mentions) and his own 20 years earlier. Nor did he predict that one day these early factory workers would organize for better pay and working conditions. But he did record his approval: “This is a work of public utility & private advantage” he remarked in his diary, something he had learned long ago.

March 6, 2015

Library in the News: February 2015 Edition

The Library’s big headline for February was the opening of the Rosa Park Collection to researchers on Feb. 4, which was also the birthday of the civil-rights icon.

“A cache of Parks’s papers set to be unveiled Tuesday at the Library of Congress portrays a battle-tested activist who had been steeped in the struggle against white violence since childhood,” wrote Michael E. Ruane of The Washington Post. “The trove, parts of which were unknown to historians, also shows Parks as a woman devoted to her family, especially to her mother and husband, Raymond, for whom she kept her hair in long braids even after he died.

“Her personal papers and keepsakes contain a much fuller story of the woman behind the movement,” wrote Laura Clark for smithsonian.com.

“But amid all the witness-to-history artifacts — a note after she’s had dinner with future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, for instance, or her ID card for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s 1968 Poor People’s Campaign, or a copy of a 1999 letter she sent to Pope John Paul II after meeting him — is the ordinary, the everyday, the mundane,” wrote Todd Spangler for the Detroit Free Press. “It is made all the more remarkable for it being hers.”

Speaking with collection curator Adrienne Cannon was the New York Times.

“I think that she felt, perhaps, limited in a way by the iconic image of Rosa Parks as the woman who refused to give up her seat in the bus,” said Cannon. “This significance that she had in the public sphere did not fully describe who she was, and I think that she perhaps wanted us to know her true self.”

WUSA (local CBS) reporter Lesli Foster spoke with Senior Archivist Specialist Margaret McAleer.

“”We always think of her as the quiet seamstress. But in her writings, we see how very courageous she was,” said McAleer.

Also running broadcast pieces were ABC This Week and NPR All Things Considered.

CBS News online also ran a story, interviewing Maricia Battle, curator of photography for the new collection.

“‘Writing things down was a way of releasing some of that pressure,’ Battle said, noting Parks’ stress from her arrest, the subsequent unfolding of the Montgomery bus boycott, and losing her job as an assistant tailor at the Montgomery Fair department store. Parks held on to much of this writing – not to mention postcards, invitations, poll tax receipts, and handwritten recipes – throughout her life.”

A selection of items from the collection are on display at the Library through March 31.

Also on display this month is the original manuscript of Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address.

The Washington Post’s Michael Ruane got a sneak peak at the document in February in advance of the special exhibit.

“Experts at the library showed the two versions of the speech, explained Lincoln’s quirky composition style and spoke about the damage the documents have incurred over 150 years,” he reported. “Even in a library conservation lab, the experts were careful to limit the exposure to light, covering the documents with large sheets of paper before and after discussing them.”

In addition to receiving the Rosa Park’s collection, the Library also received the papers of American composer Marvin Hamlisch.

Running stories were Fine Books & Collections Magazine and AllAccess.com.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers