Library of Congress's Blog, page 145

June 19, 2015

Celebrating Juneteenth

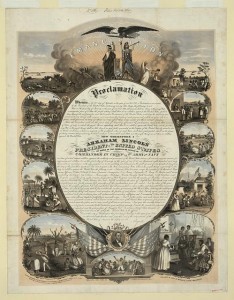

Emancipation Proclamation. Lithograph by L. Lipman, Milwaukee, Wisc., Feb. 26, 1864. Prints and Photographs Division.

This year marks the 150th anniversary of Juneteenth, the oldest nationally celebrated commemoration of the ending of slavery in the United States.

On June 19, 1865, Major Gen. Gordon Granger led Union soldiers into Galveston, Texas, with news that the Civil War had ended and slavery was abolished – two years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

Pres. Abraham Lincoln’s edict had little impact on the people of Texas, since there were few Union troops around at the time to enforce it. But, with the surrender of Gen. Robert E. Lee in April 1865 and the arrival of Gen. Gordon Granger’s regiment in Galveston, troops were finally strong enough to enforce the executive order. Newly freed men rejoiced, originating the annual “Juneteenth” celebration, which commemorates the freeing of the slaves in Texas.

Although Juneteenth has been informally celebrated each year since 1865, it wasn’t until June 3, 1979, that Texas became the first state to proclaim Juneteenth an official state holiday.

The day of Jubelo. 1865. Prints and Photographs Division.

So, why the two-and-a-half year delay? According to Juneteenth.com, some possible explanations include a murdered messenger, the deliberate withholding of news by plantation owners, and that federal troops actually waited so that slave owners could benefit from one last cotton harvest.

The Library’s “Voices from the Days of Slavery” presentation contains several interviews with former Texas slaves.

The Library’s collections are particularly wealthy in resources regarding African-American history and slavery, including photographs, documents and sound recordings. This web guide is a good place to start.

You can also read more about Juneteenth in this blog post.

June 18, 2015

The Battle of Waterloo

Meeting of the generals Wellington and Blucher, after the conclusive Battle of Waterloo, at the farm La Belle Alliance. 1816. European Division.

(The following is a guest post from Taru Spiegel, reference specialist in the Library’s European Division.)

Today marks the 200th anniversary of the history-changing Battle of Waterloo in 1815. This engagement ended in the conclusive defeat of Napoleon and his French generals and was a costly victory for the Anglo-Dutch, Belgian and German forces. The expression “to meet one’s Waterloo,” or to face a final defeat, refers to this event.

Scholars have presented many reasons for the importance of this fight. Among others, it has been argued that a victory by Napoleon might have resulted in a much earlier united and liberal Europe.

Napoleon. Prints and Photographs Division.

Napoleon, the revolutionary turned Emperor of the French, was forced to abdicate in 1814 and was exiled after 23 years of warfare and conquest of Europe. However, he made a stunning comeback in 1815. The “dancing” Congress of Vienna (so called because of the lavish balls and social events that took place while the ambassadors of the European states were in the city to restore order after the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars), busily re-dividing Europe after Napoleon, had barely concluded business when the Battle of Waterloo was fought nine miles south of Brussels. Both sides incurred devastating losses. In the words of one of the victors, the Duke of Wellington, it was “the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life.”

The Library of Congress has hundreds of works in several languages pertaining to or inspired by the Battle of Waterloo. These range from historical accounts to memoirs, novels, poems, photographic prints, music and maps.

One notable and generously illustrated work in the Library’s collections was published in 1816, a year after the battle. This early work on Waterloo by Jan Scharp, “Gedenkzuil van den Nederlandschen krijgsroem in Junij 1815″ (“Memorial column of the Netherlands military glory in June 1815″) is a depiction of the history of the battle from the Dutch-Belgian point of view. In the manner of the time, the book notes in detail the role of the Dutch royal family in the war effort and subsequent commemorations and the fact that the Prince of Orange himself was wounded in the battle.

His Royal Highness the Prince of Orange with his arm in a sling after being wounded in the battle of Waterloo. 1816. European Division.

The book was a gift to correspondent L. Boyer from Frederica Luise Wilhelmine, the Dowager Duchess of Braunschweig (aka Brunswijk or Brunswick), who was closely related to two of Napoleon’s adversaries, Prince Willem of the Netherlands and Duke Friedrich Wilhelm of Braunschweig.

A variety of works on Napoleon himself can also be found in the Library’s collections, including music, photographic prints, books, manuscripts and this film from 1909 depicting various events in the life of the French leader, including Waterloo.

{mediaObjectId:'E62055F6772D023AE0438C93F028023A',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

And, if you are curious about how Napoleon handled mining rights in France – of importance because the French military needed large quantities of iron, lead and other resources while fighting in the Napoleonic Wars – you can learn more with this blog post from the Law Library of Congress.

It’s also important to note that the United States acquired Louisiana from France in 1803 during the time that Napoleon ruled. This presentation tells the story through a selection of materials in the Library.

June 17, 2015

Inquiring Minds: Music Scholar Uncovers Forgotten Songs from “My Fair Lady”

Dominic McHugh

The musical “My Fair Lady,” based on George Bernard Shaw’s “Pygmalion,” has been praised as the “perfect musical” and is filled with some of the most recognized songs in American musical theater. The hit show opened on Broadway in 1956 and starred Julie Andrews as Eliza Doolittle and Rex Harrison as Professor Henry Higgins. Harrison reprised his role in the 1964 film version that also starred Audrey Hepburn as Eliza.

Audiences, myself included, have delighted in the ambiguous relationship of Eliza and her Higgins and have happily sung along to such tunes as “The Rain in Spain,” “I Could Have Danced All Night” and “On the Street Where You Live.” The show included other songs that never saw the Broadway stage and thus a way into our hearts. Five songs were scrapped before rehearsals even began, with two more songs and a ballet sequence cut prior to the Broadway debut.

Dominic McHugh, lecturer in musicology at the University of Sheffield, uncovered the musical numbers while conducting research at the Library of Congress. Last month, the songs were performed for the first time in nearly 60 years during a concert he put on at Sheffield.

We caught up with him to talk about his discovery.

Tell me a little about yourself? What brought you to the Library of Congress for research?

I first came to the Library in October 2006 to begin my doctoral research on “My Fair Lady.” I was a PhD student at King’s College London from 2006 to 2009 and wrote a dissertation about the musical’s genesis and sources. Subsequently, I developed my thesis into a book, “Loverly: The Life and Times of ‘My Fair Lady,'” which was published by Oxford University Press in 2012. I’ve also used my research to write program notes for the BBC Proms and Edinburgh Festival, and I also spoke about it on a BBC TV documentary called “Michael Grade’s Stars of the Musical Theatre.”

This research led you to discover songs thought to be lost from the original performance of “My Fair Lady.” How did you make the discovery? What collections were you using? What was going through your mind when you found them?

I was so lucky from the start of my visit to the Library to have the help and guidance of the wonderful Mark Eden Horowitz [of the Library’s Music Division]. On the last day of my first visit, Mark showed me an inventory of the Warner-Chappell Collection, which came from the publisher of “My Fair Lady.” The collection is stored off-site, so I had to return in 2008 to look at it. It turned out to be 16 boxes containing the original band parts used by the players in the Broadway pit in 1956. But the most amazing materials were the handwritten scores by the dance arranger Trude Rittmann and the orchestrators Robert Russell Bennett, Phil Lang and Jack Mason. Rittmann’s scores showed the extent of her input into the show: she didn’t just arrange the dances but also wrote the routines for the overture, entr’acte, scene change music and reprises. It was also exciting to find a couple of scores in Frederick Loewe’s hand, including an intermediate version of “Why Can’t the English?” called simply “The English.”

Can you tell us about the musical numbers?

The orchestrations for the three numbers [cut before the Broadway debut] were there: “Come to the Ball,” the “Decorating Eliza” ballet and “Say a Prayer for Me Tonight.” I’d always wondered what the ballet sounded like, so this was the most exciting discovery. I also came across several alternative orchestrations for “On the Street Where You Live,” the verse for which had to be revised during the tryouts because it wasn’t funny enough.

(Edit: It is also interesting to note that “Say a Prayer for Me Tonight” was finally heard by the public when Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe used the song for their musical “Gigi” a little later.)

Why were they dropped from the performance?

The three numbers were dropped because the show was simply too long. They formed a long sequence of perhaps 15 minutes in which Eliza returns from the ball, Higgins persuades her to go on with her lessons (“Come to the Ball”), she has more lessons (ballet) and then on the night of the ball she asks Mrs. Pearce to pray for her (“Say a Prayer for Me Tonight”). Lerner realized it could all be removed without affecting the show, and everyone felt the ballet was too cramped on the library set, so Lerner wrote a two-minute scene of dialogue instead. Loewe also wrote a completely different “Embassy Waltz,” which shows how much they worked on the final scenes of Act 1 during the tryouts.

Did you learn anything that you may previously not have known?

I hadn’t really appreciated how dark the ballet must have been until I saw the music. It was conceived as a nightmare and has music to fit! I also hadn’t realized that “Why Can’t the English” had caused so much trouble until I found various versions of it in the Warner-Chappell Collection, all of which dated from January 1956. They didn’t come to the final version until the very end of rehearsals.

How is finding them and reintroducing them significant to musical society/enthusiasts/scholars/educators?

As one of the most enduringly popular musicals of the 1950s, “My Fair Lady” remains of interest to a general audience to a greater extent than most of the other works written in that period. I decided to put on this concert with the cut material because it’s easy to take great works of art for granted, without appreciating how their apparent ease and fluency came about. Lerner and Loewe worked for several years on this musical, and it was a tough nut to crack. But it’s so famous that it’s almost a cliché that people dismiss without a second thought. So I felt that if we could look at some of the other material they wrote for the show – most of which is pretty good and all of which is interesting – it would help to illustrate the high level of self-criticism Lerner and Loewe had to exercise in order to get it right. Aside from all of that, I was dying to hear the ballet and the other cut numbers for which original orchestrations survived, and I was thrilled to finally get that opportunity. It was especially wonderful to share the experience with my students, who played in the orchestra. One of them, Matthew Malone, conducted and did a lot of restoration work on the orchestrations too, so it felt like scholarship in action.

You’ve conducted other research at the Library and produced publications on “My Fair Lady” and other American musicals. Why the interest there?

The scholarly field of the American musical theater has considerably expanded in recent years, and I was lucky to enter it when it was just taking off. I had always loved musicals as a child, and not just in a casual way – I had all the Astaire-Rogers movies on video by the time I was 10 years old, for instance. As a teenager I then became obsessed with Italian opera, but while I was in high school I was musical director for quite a lot of shows, including “Kiss Me, Kate.” I read music at King’s College London, and in my third year I was lucky to attend a course on Broadway, taught by Professor Cliff Eisen. Cliff is a Mozart scholar, but he decided to introduce this course and I realized I already knew the entire repertoire and really loved it. As an adult I was able to appreciate its richness in a different way, so I abandoned my plans to do a PhD on Verdi and did “My Fair Lady” instead!

Can you tell us about other collections you’ve used? Any collections and/or items you’ve found most illuminating? Any other interesting discoveries?

By now I’ve looked at a large number of the musical theater collections in the Library. My favorite is the Richard Rodgers collection, because his sketches are extraordinary. He seems to have had an unprecedented ability to write out many of his songs almost fully formed. My heart is in the Lerner and Loewe collections. Their relationship is richly charted through Loewe’s manuscripts in particular, though I also love some of the correspondence in the Lerner collection, such as fan mail from Harold Arlen (composer of “The Wizard of Oz”). The Irving Berlin collection is great because he lived to be over 100 years old, and there’s some wonderful correspondence with Fred Astaire in it. They were great friends, and it’s fascinating to see how domestic their letters were.

I recently explored the Wright and Forrest collection, which I hope will form the basis of a future book project for me. They wrote hundreds of songs based on the music of classical composers, and I was stunned to find that they kept the published sheet music by those other composers, annotated with notes on how they were going to turn them into songs.

I also recently looked at the Hugh Martin papers – he was the composer of “The Trolley Song” and “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” – and was impressed by how many songs he wrote for projects such as “Make a Wish” and “Look Ma, I’m Dancin,'” which weren’t particularly successful. In the Harold Rome collection I found a sketchbook for his musical “Fanny,” which indicated that he went and researched French folk songs before writing the score; to anyone who knows the show, that makes a lot of sense, and I was elated to find it. I should also mention the Cole Porter collection, which includes some brilliant sketches and manuscripts. At the moment I’m working on an edition of his letters, so I’ve spent some happy hours looking through this collection!

Why do you think it’s valuable for the Library to preserve such historical collections, and what do you think the public should know about the Library’s mission to collect and preserve our cultural and historical heritage?

At a time when public services are becoming more and more accountable, institutions such as the Library are an easy target for criticism. Why should money be poured into preserving bits of paper written on by dead people? But all the artists and other figures whose papers are held at the Library of Congress have created works of art that define what it means to be human: to be American or European, to be young or old, a man or woman, and so on. The arts and humanities represent our liberty – people have fought wars so that we can continue to live our lives with the freedom to be who we want to be, and that freedom is often best expressed through words, music songs or art. The American Musical Theater collections at the Library show this brilliantly, whether in the songs of Cole Porter, the music of Leonard Bernstein or the musicals of Howard Ashman. It doesn’t matter whether we all like the works of these writers. No price can be put on what they represent. America is lucky to have this unique library with its unparalleled collections, and I hope it continues to receive the support it deserves in preserving the country’s cultural heritage.

June 12, 2015

Book Festival Blogging

Crowd at 2014 National Book Festival held at the Washington Convention Center. Photo by Colena Turner.

Calling all readers, the new Library of Congress National Book Festival blog launched this week! It’s one of the many ways that we will be celebrating the 15th anniversary of the nation’s premier celebration of books and reading.

This year’s festival will take place during Labor Day weekend on Saturday, September 5, 2015, at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in Washington, D.C., from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. A record 150 authors are scheduled to present in a range of pavilions including Children, Teens, Picture Books, Biography & Memoir, Contemporary Life, Food, Fiction, Graphic Novels, History, Mysteries & Science Fiction, Poetry & Prose, Science, Special Programs and few more yet to be announced.

The blog will be a way to keep you up to date on authors, activities and how you can take part. Already there are three blog posts up, including a Q&A with this year’s poster artist Peter de Sève as well a look back at all of the posters over the festival’s 15-year history.

We invite you to follow along on the festival blog, as well as we countdown to the summer’s biggest literary event!

June 11, 2015

Inquiring Minds: How a New Walt Whitman Poem was Found at the Library of Congress

(The following is a post written by Peter Armenti from the Poetry and Literature Center’s blog, From the Catbird Seat. Armenti spoke with a researcher who discovered a new Walt Whitman poem in the Library’s collections.)

Walt Whitman enthusiasts were treated to a surprise last December when news broke that Wendy Katz, an associate professor of art history at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, had discovered a new poem by Whitman. The poem, titled “To Bryant, the Poet of Nature,” was uncovered by Katz in May 2014 as she examined penny press newspapers in the Library of Congress’s Newspaper and Current Periodical Reading Room while a Fellow in Residence at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Appearing on page 2 of the June 23, 1842, issue of the Democratic Republican New Era, the poem was found serendipitously by Katz while conducting research for a forthcoming art history book, “The Politics of Art Criticism in the Penny Press, 1833-1861.”

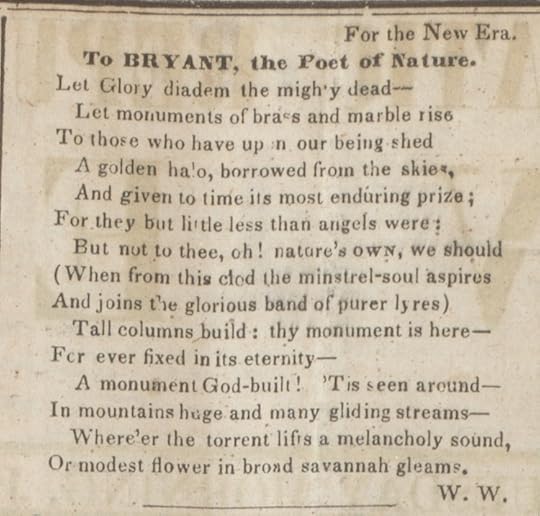

“To BRYANT, the Poet of Nature.” Democratic Republican New Era, June 23, 1832, page 2.

Dr. Katz, who split her time in Washington, D.C., conducting research at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, and the Library of Congress was kind enough to discuss her discovery of the poem in an email exchange with me.

Whereas many recent discoveries of “lost” literary works are due to the increasing availability of keyword-searchable full-text databases that provide access to historical newspaper and periodical content, Dr. Katz found the Whitman poem through a more traditional method:

My typical day [at the Library] really was spent at one of the reading room tables, with foam supports, not browsing, but standing and methodically going through bound newspaper volumes. I would spend eight to 10 hours or more doing so. I identified volumes through the Library’s online catalog, but had assistance from the Newspaper circulation staff, who often could help me interpret the holdings more precisely. Since my time in Washington was short, I prioritized bound volumes, on the principle that subscription databases and microfilm “might” be obtainable elsewhere.

Dr. Katz took advantage of the Library’s late evening hours during the week and its Saturday hours to complete her research. She spent the first three months of her time at the Library going through the Library’s nearly complete run of New York’s Morning Courier and New-York Enquirer, noting that it’s “one of the most important and longest-running Whig papers during this period, and as far as I know, not microfilmed or digitized.” Dr. Katz also noted that the paper is “a blanket sheet—literally 3 or 4 feet high and wide,” and that while skimming the pages is difficult, “to do so online or on microfilm would take ten or more times as long, because you could not get anywhere near all of one page’s contents in any particular screen or view.”

After she finished searching the Morning Courier and New-York Enquirer, she moved on to papers that had shorter runs, at least in the Library’s collection, reviewing about 35 papers in all. It wasn’t until May, however—the final month of her Library research—that the Democratic Republican New Era attracted her attention. As Dr. Katz describes:

Democratic Republican New Era, June 23, 1832, page 2. “To BRYANT, the Poet of Nature” appears at top of column 4.

I had started to find quite a bit of coverage of the arts in the Sunday weeklies that had started off with a Democratic bent to them—the Sunday Dispatch, and Atlas, for example, but also the Mercury—many of them of course became Republican by the 1850s. So that gave me a particular interest in the newspapers in that ‘circle’—but I was also trying hard to work through some of the newspapers that like the New Era had only a relatively few issues in the [Library’s] collection, to see if I could get a feel for whether they would be productive sources and should be pursued. But I didn’t single the New Era out in advance, or have particular hopes for it.

Her hopes changed dramatically on May 22, at about 8 p.m., when she came across the poem “To Bryant, the Poet of Nature,” written by “W.W.” Even though the author’s full name wasn’t given, she had little doubt the poem was by Whitman:

Since I really do go through the newspapers page by page, I had noticed in earlier issues mentions (usually praising his work) of Whitman, first by Levi Slamm, and then by Parke Godwin. So when the “W.W.” poem appeared shortly after one of these comments, I was pretty immediately sure that it must be by him. Though nothing in the composition or language of the poem was recognizable to me as Whitman per se, the subject–(William Cullen) Bryant, who I knew he admired, but also the idea of a poet’s fame—also pointed toward Whitman, for me. As did the fact that I knew he had edited a Democratic paper himself so had contacts and patronage within those circles.

Despite Dr. Katz’s certainty, her husband, the Whitman scholar Kenneth Price, “with his track record of identifying some 3000 Whitman documents in the National Archives,” was initially more skeptical. He was eventually swayed by Katz’s arguments, which were published in the Fall 2014 issue of Walt Whitman Quarterly Review (“A Newly Discovered Whitman Poem about William Cullen Bryant“).

When I asked Dr. Katz about the contributions of Library staff to her research, she offered words of praise for employees in the Newspaper and Current Periodical Reading Room:

I worked most closely with the circulation staff, who helped me identify the bound volumes I needed, which sometimes weren’t where I thought they were. They were really wonderful; thoughtful, always helpful, interested in my work, with a really good balance between keeping the materials accessible to researchers and making sure that best practices for conservation were in place.

“To BRYANT, the Poet of Nature.” [Transcription]

Let Glory diadem the mighty dead—

Let monuments of brass and marble rise

To those who have upon our being shed

A golden halo, borrowed from the skies,

And given to time its most enduring prize;

For they but little less than angels were:

But not to thee, oh! nature’s OWN, we should

(When from this clod the minstrel-soul aspires

And joins the glorious band of purer lyres)

Tall columns build: thy monument is here—

For ever fixed in its eternity—

A monument God-built! ‘Tis seen around—

In mountains huge and many gliding streams—

Where’er the torrent lifts a melancholy sound,

Or modest flower in broad savannah gleams.

W.W.

For further reading and research, make sure to check out the Library’s Pinterest board on Walt Whitman, which you can read more about here. For more stories on researchers and scholars using the Library’s collections, check out other blog posts in our “Inquiring Minds” series.

June 9, 2015

LC in the News: May 2015 Edition

In May, the Library’s Rosa Parks Collection continued to make news. Her niece, Sheila Keys, visited the Library of Congress to present a lecture on her book about her aunt. She, along with several other relatives, also had the opportunity to view items from the collection.

“I was pleased that it would go to a place where students and the public could view it, take from it and learn something from it, from her, from her humility,” Keys told the Associated Press. “The public will gain some knowledge, some insight into the wisdom of this woman.”

The AP story ran in other national outlets including ABC News and the Huffington Post.

The Library’s Veterans History Project made several headlines during May, for commemorations of Memorial Day and V-E Day.

Lily Rothman wrote a piece for Time Magazine and spoke with family members of veterans whose collections are part of the archive, as well as volunteers who collect the oral histories.

“If veterans are not interviewed before they pass on then no one else will be able to get that same perspective and story from them. It’s very important for us to continue doing this project so that everybody, no matter when it was in history, can know how it really was,” said Hetal Shah, who has been volunteering since she was 15.

Newsweek ran excerpts from the VHP collections that recalled World War II.

Speaking of wartime history, the Library’s collection of Civil War stereographs was featured on hyperallergic.com.

“There’s a less common breed of stereoscopic images that enthusiasts tend to drool over: the ones made by small town producers, for which very few prints were made, and for which the negatives no longer exist,” wrote Laura C. Mallonee. “Remarkably enough, the Library of Congress has acquired 540 of them.”

The National Journal put the spotlight on a collection of early American war and health posters.

Reporter Caroline Nyce called them “quirky and sometimes harrowing.”

June 5, 2015

A Hole-some Treat

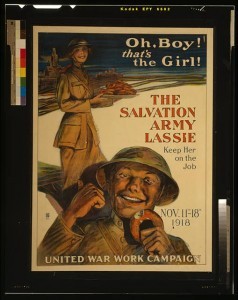

Poster advertising the Salvation Army “lassies.” 1918. Prints and Photographs Division.

Doughnuts are as quintessential to America as apple pie. Who hasn’t happily licked glaze off his or her fingers or made a mess with powdered sugar? If there were never to be a Krispy Kreme, Dunkin’ Donuts, LaMar’s or neighborhood mom-and-pop bakery, life as we know it would be a less cheery place … these are calories many of us don’t mind.

So it should come as no surprise that a holiday has been set aside to celebrate these fried confections. National Doughnut Day is the first Friday in June (today!) and actually honors the Salvation Army “Lassies” of World War I.

The original Salvation Army doughnut was first served by the nonprofit organization in 1917. During WWI, the lassies were sent to the front lines of Europe, where they made home-cooked foods and provided a morale boost to the troops. Two Salvation Army volunteers – Ensign Margaret Sheldon and Adjutant Helen Purviance – came up with the idea of providing doughnuts. Sheldon wrote of one busy day: “Today I made 22 pies, 300 doughnuts, 700 cups of coffee.” Often, the doughnuts were cooked in oil poured into a soldier’s metal helmet.

National Doughnut Day started in 1938 as a fundraiser for the Chicago Salvation Army. Its goal was to help the needy during the Great Depression and to honor the Salvation Army Lassies of World War I, who were the only women outside of military personnel allowed to visit the front lines.

Sylvia Coney, a canteen worker from New York, serves doughnuts on the Italian front. 1917 or 1918. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Library’s collections are full of interesting and obscure items on the breakfast treat. A 1918 Cleveland Advocate newspaper article in The African-American Experience in Ohio presentation states that a “search through the American expeditionary force fails to disclose any man who sees nothing to the doughnut but the hole.”

“Don’t forget the Salvation Army, always remember my doughnut girl,” sings the chorus of 1919 song sheet that can be found in the Historical American Sheet Music presentation.

An excerpt from Horatio Nelson Taft’s diary, written Feb. 21, 1862, alludes to the fact that his wife is frying doughnuts in the kitchen at the time of the writing.

The Library’s Prints and Photographs Online Catalog also has historical images featuring donuts. Simply searching for the term there and in American Memory should satisfy your scholarly sweet tooth.

June 2, 2015

Creating Cartoons: Art and Controversy

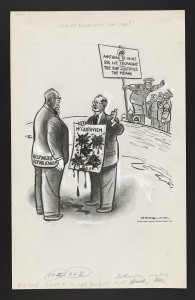

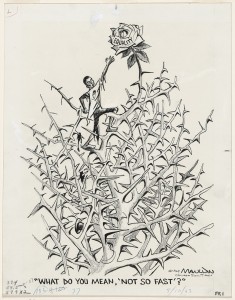

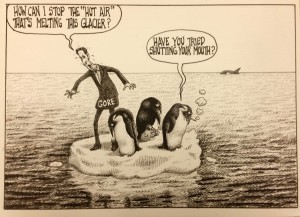

(The following is an article written by Sara Duke and Martha Kennedy, both of the Prints and Photographs Division, for the May/June 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

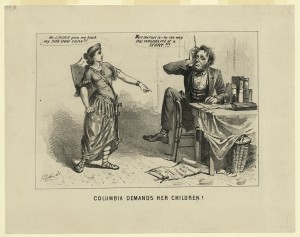

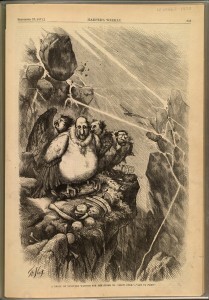

The Library’s vast collection of cartoon art chronicles the nation’s political controversies from its founding to the present.

Controversy sparks and fuels the art of political cartooning. Political cartoonists thrive in a climate that allows contention and freedom of expression. The compelling union of image and word that characterizes political cartoons sets them apart from other art forms, endowing them with the potential to inform, provoke and entertain.

Occasionally, cartoons can trigger violent reactions like those that occurred on Jan. 7, 2015. On that day, five cartoonists for Charlie Hebdo magazine were killed by Islamic extremists in Paris. A decade earlier, cartoon depictions of the prophet Mohammed by the Danish newspaper Jyllands- Posten sparked violent protests worldwide.

Political cartoons also have the power to generate healthy public debate, highlight pressing issues of the day, move some viewers to consider both sides of an issue and take positive action. Cartoons have contributed to political change by unmasking and condemning corruption, smear tactics and obstruction of justice. They have hastened the downfall of flawed leaders such as Sen. Joseph McCarthy and President Richard Nixon. And they have championed– and mocked–political movements such as the struggle for women’s suffrage and civil rights.

The following sampling from the vast array of political cartoon art in the Library’s collections provides just a glimpse of the rich holdings that can be explored online, and in person in the Prints and Photographs Division. The emphasis is on those that aroused controversy and likely contributed to the process of political and social change.

All images are from the Prints and Photographs Collection.

The horse “America” throws its master, King George III, in this 1779 etching published in Westminster by Wm. White.

President Abraham Lincoln is blamed for the Civil War’s huge human toll and for deflecting the issue with his notorious storytelling in this 1864 cartoon by Joseph E. Baker.

Thomas Nast depicts corrupt New York politician William M. (“Boss”) Tweed and his cohorts as vultures picking over the remains of New York City government in this cartoon published in Harper’s Bazaar on Sept. 3, 1871.

Cartoonist Herbert Block (Herblock) invented the term “McCarthyism.” But his cartoon, published in The Washington Post on June 17, 1951, shows that he understood that the smear campaign used to combat communism was not the work of Wisconsin Sen. Joseph McCarthy alone but the result of others going along with the idea.

The climb to reach equality was a long and thorny one, as this cartoon by Bill Mauldin, which appeared in the Chicago Sun-Times on May 10, 1963, depicts.

Matt Wuerker offers this visually appealing take on the rise of the Tea Party and increasing polarization in national politics in this cartoon, which appeared in Politico Magazine on Oct. 21, 2009.

Ann Telnaes’ cartoon, distributed by Tribune Media Services on June 20, 2003, juxtaposes the view of some Americans about the role of religion in our society with that of the Iranians.

Sean Delonas lampoons former Vice President Al Gore’s propensity for talking about global warming in this 2006 cartoon that appeared in the New York Post.

May 29, 2015

“First Among Many”

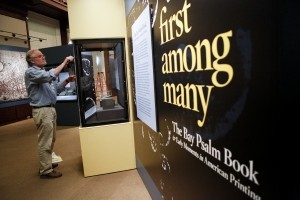

(The following is a story featured in the Library of Congress Gazette, the staff newsletter, written by editor Mark Hartsell.)

Chris O’Connor, lead exhibition production specialist, prepares the “First Among Many: The Bay Psalm Book and Early Moments in American Printing” exhibition for the June 4 opening in the South Gallery. Photo by Shawn Miller.

The printing press that helped spread world-changing ideas of revolution, liberty and self-governance through early America grew from a humble beginning: a small, error-filled book of religious devotion, produced by a locksmith for settlers forging a home in the North American wilderness.

A new Library of Congress exhibition explores early printing in the American colonies, from that first book to the broadsides, pamphlets, newspapers and books that, over the next 150 years, helped shape a revolution and a new nation.

“First Among Many: The Bay Psalm Book and Early Moments in American Printing” opens June 4 and runs through Jan. 2.

The exhibition, located in the Jefferson Building’s South Gallery, is made possible through the support of philanthropist David M. Rubenstein, chairman of the Library’s private-sector advisory group, the Madison Council.

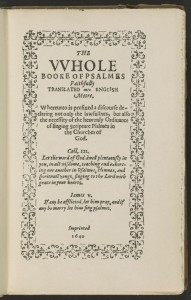

At the exhibition’s heart are two copies of the Bay Psalm Book, a small volume with a big title and a historic distinction: “The Whole Booke of Psalmes Faithfully Translated into English Metre” stands as the first book published in what now is the United States.

“The Whole Booke of Psalmes Faithfully Translated into English Metre,” Cambridge, 1640. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

One copy was drawn from the Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division; the other, on display through Aug. 8, belongs to Rubenstein.

“The Library is extremely grateful to David Rubenstein for sharing his extraordinary copy of the Bay Psalm Book,” Librarian of Congress James H. Billington said. “The celebration of this book is the impetus for the Library’s exhibition. The Bay Psalm Book is a book of many firsts – the first English-language book in North America, the first book of American poetry and the first instance in a long and vital history of printing in America.”

The exhibition also showcases more than 30 other treasures that followed the Bay Psalm off the printing presses of early America: among them, the Dunlap Broadside of the Declaration of Independence; “Poor Richard’s Almanack” by Benjamin Franklin; “Common Sense” by Thomas Paine; “The Federalist,” essays by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay; “The Power of Sympathy,” the first novel printed in the colonies; and the Algonquian Indian Bible, the first complete Bible printed in the Western Hemisphere.

“It’s meant to be more than, say, just a string of pearls,” said Mark Dimunation, chief of Rare Book. “This exhibit really tells the story of how printing is introduced to America and how it actually participates in the growth and development of revolutionary America. It’s different than in other places.”

Still, the start and heart of the exhibition is the Bay Psalm Book, a small volume of verse – meant for singing in worship services – produced in 1640 by English settlers in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Creating such a book in that time and place – the colony was founded in this New World wilderness only a dozen years earlier – was an enormous project.

Printing a book required the settlers to import a press, paper and type. They also had to translate 150 psalms from the original Hebrew, then cast the new text into rhyming verse suitable for singing. The printer, Stephen Daye, was a locksmith just apprenticing in this new trade.

“These are very primitive conditions. They’re not far into settlement. They’re still building buildings,” Dimunation said. “It’s a huge undertaking.”

The result, in some ways, wasn’t great.

The print job was overinked, the typesetting coarse, the text rife with typographical errors and inconsistent spellings (is it “psalm” or psalme”?).

The verse frequently is awkward, as in the famous Psalm 23:

The Lord to mee a shepheard is,

want therefore shall not I,

Hee in the folds of tender-grasse,

doth cause mee downe to lie. …

Yea though in valley of deaths shade

I walk, none ill I’le feare:

Because thou art with mee, thy rod,

And staffe my comfort are.

“None of that carries any real merit as criticism of the book,” Dimunation said, considering the historical importance of the volume.

The Bay Psalm actually wasn’t the first piece printed on that new press in Massachusetts Bay Colony. Daye earlier had produced “Oath of a Freeman,” a loyalty oath he printed as a broadside in 1639. No copies survive.

The Bay Psalm is the first book, and the first surviving document, to be printed in what’s now the United States. And the first book of poetry. And the first piece of printed music: In the ninth and final printing of the book, music was added to accompany the text.

Though some 1,700 copies were produced over those nine printings, only 11 survive today – a consequence of constant use and the passage of time.

“They’re very scarce,” Dimunation said. “They have the same characteristic that children’s literature has: They’re used so frequently that they get used completely, get used up.”

“The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America,” Baltimore, 1777. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

The Library acquired its copy, still in the original binding, in the 1960s. The book lacks the original title page, bearing instead an old calligraphic facsimile that, Dimunation said, frequently fools viewers into thinking it’s the real thing. The volume also is missing 12 pages. Years before the Library acquired the book, those pages were removed to complete a copy now held by the New York Public Library.

Rubenstein purchased his copy at auction in 2013 – the first time in more than 66 years a copy of the Bay Psalm was sold on the open market. That copy is complete and includes the original title page – one of only seven surviving copies that do so.

Around those two volumes in the exhibition, Dimunation said, are some of the great pieces of Americana: two printings of the Declaration of Independence; an extraordinarily rare Thomas Jefferson pamphlet, “A Summary View of Rights of British America,” annotated in Jefferson’s own hand; “Common Sense”; and “The Federalist,” also annotated by Jefferson.

“You could teach the Revolution with these books alone,” Dimunation said.

But it started with the humble, inelegant volume produced by a small group of settlers carving out a new home in the New World, for use in daily acts of devotion.

“It’s an ordinary book, in a way, especially in that period,” Dimunation said. “To them, this would be quite ordinary. To us, this book is hardly ordinary.”

An online version of the exhibition will be made available at www.loc.gov/exhibits/ .

May 27, 2015

Page From the Past: A Show About Nothing

Script page from pilot episode of “Seinfeld.” Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division.

When “The Seinfeld Chronicles” first aired on NBC on July 5, 1989, no one could have predicted that the “show about nothing” would become a cultural phenomenon. Inspired by real-life people and events, the show followed the life of a stand-up comedian and his friends.

The pilot episode (pictured left), written by show creators Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David, featured sidekick George Costanza, played by Jason Alexander, and neighbor Kessler (later Kramer) played by Michael Richards. The plot centered on Jerry’s uncertainty about the romantic intentions of a female houseguest. Like the 179 episodes that followed over the series’ nine seasons, hilarity ensued.

But not everyone was laughing at first. The show was rated poorly by a test audience. Fortunately, television critics were kinder and network executives persisted in finding a spot for it in the 1990 line-up. Renamed “Seinfeld,” the show returned to the air on May 30, 1990, with an episode that introduced the character of ex-girlfriend Elaine Benes (Julia Louis-Dreyfus). With a slow but growing following, the show reached Number 1 in the Nielsen ratings in its sixth season. More than 76 million viewed the finale on May 14, 1998–58 percent of all viewers that night–making it the fourth-most-watched series finale in U.S. television history.

The Library of Congress holds videotapes of all of the “Seinfeld” episodes, which were registered for copyright by Castle Rock Entertainment. Registrations were accompanied by deposit copies that became part of the Library’s Motion Picture and Television collections, along with “descriptive materials,” which range from a synopsis to a complete script.

(The above article is featured in the May/June 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers