Library of Congress's Blog, page 141

September 24, 2015

And the Word Was Made Beautiful

Pope Francis has moved among us, here in Washington, D.C., for a timeand one lasting result of his visit can be viewed, starting Saturday, at the Library of Congress: a breathtakingly beautiful Apostles Edition of The Saint Johns Bible, the first Bible entirely hand-made and illuminated in more than 500 years.

The rare Bible was presented to the Library of Congress and the American people by Saint Johns Abbey and University in Minnesota, which oversaw the creation of the hand-drawn and illuminated original, completed in 2011. The gift, in honor of the Pope and commemorating his visit to the United States, was made possible by GHR Foundation. The Pontiff blessed it as it was presented to Librarian of Congress James Billington today.

The Pope blesses the gift Bible. On left, Abbot John Klassen, Sen. Blunt and Dr. Billington; on right, Monsignor Mark Miles, Speaker Boehner, SJU President Michael Hemesath and GHR Foundation CEO Amy Goldman. Photo by Heather Reed, Office of the Speaker

Also present at the ceremony in House Speaker John Boehners office were Speaker Boehner, Sen. Roy Blunt (R-MO), who heads Congress Joint Committee on the Library of Congress, Saint Johns University President Dr. Michael Hemesath, Abbot John Klassen, OSB and GHR Foundation CEO Amy Goldman.

The volume will be on view on the north side of the Great Hall in the Librarys Thomas Jefferson Building at 10 First St., S.E., in Washington, D.C. Saturday, Sept. 26, 2015 through Saturday, Jan. 2, 2016. The Bible can be viewed Monday through Saturday, 8:30 a.m. 4:30 p.m.

There are only 12 sets of the Apostles Edition in existence (each set takes seven volumes to encompass the full Bible), including the one donated to the Library. A separate set was presented to the Pope and is available to scholars at the Vatican Library. The original Saint Johns Bible manuscript is in the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library at Saint Johns Abbey and University. The Bible is a work of art with more than 1,130 pages and 160 illuminations that reflect life in the modern era, measuring 2 feet tall and 3 feet wide when open.

The illuminations bring to life familiar scriptural passages from a modern perspective, both in terms of conveying a multicultural humanity and representations of science, technology, and space travel, in addition to other more contemporary historical events.

St. Johns and GHR Foundation stated that the gift was made in acknowledgement of the Popes devotion to scripture; his concern for the poor, sick and marginalized and for the dignity of all people; his care for creation; and his commitment to justice for all.

The Library is the home of an extensive array of materials reflecting the worlds broad and varied religious heritage. Its holdings range from a Gutenberg Bible and a collection of more than 1,500 other Bibles to Jewish Talmuds, Tibetan texts, ancient Buddhist scrolls and rare editions of the Quran.

September 23, 2015

Forgive Us, Yogi, If We Laugh Through Our Tears

The beloved Yankees catcher and phrase-mangler Yogi Berra is with us no more.

The man who famously said You can observe a lot by watching amused us a lot, by speaking. And, as an 18-time All-Star who played on 10 championship World Series teams, won three MVP awards, hit 358 home runs and held the record for most hits in World Series play (71), he was a giant in the game of baseball. (Thanks to David Olney of ESPN insider for those stats).

Although we grieve his passing, it is not possible to think of Yogi and the many wonderful phrases he left behind without a chuckle. Things like:

Its déjà vu all over again.

If the people dont want to come out to the ballpark, nobodys going to stop them.

If you dont know where you are going, you might wind up someplace else.

The future aint what it used to be.

I always thought that record would stand until it was broken.

I never said most of the things I said.

And, on a more serious note: It aint over till its over.

Well, for Mr. Berra, its over. But if you want to remember him in the future, one resource is the Sports Byline USA audio collection, here at the Library of Congress, which contains this interview with Ron Barr on March 23, 1998.

Let us leave you with this Yogi Berra quote:

I think Little League is wonderful. It keeps the kids out of the house.

The Joy of Reading

The following is an article, written by Jennifer Gavin of the Library’s Office of Communications, for the September/October 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, from left, acting Surgeon General Boris D. Lushniak, NFL Hall of Famer Warren Moon and Chef Pati Jinich participate in a “Let’s Read! Let’s Move!” event at the Library of Congress. Courtesy of U.S. Department of Education.

The Library of Congress promotes the pleasure and power of reading.

Thomas Jefferson famously stated, “I cannot live without books,” but he didn’t think the nation should have to live without them, either. So, in 1815, he offered his collection of 6,487 volumes–the finest private library in the U.S.–to Congress to replace its books and maps, destroyed by British arson during the War of 1812.

The Enlightenment concept that a free people–if well-informed–could be their own best masters was an idea close to Jefferson’s heart. And it is a major reason the Library of Congress, in addition to being Congress’ touchstone for research and the de facto national library of the United States, also considers literacy promotion to be part of its mission.

LITERACY PARTNERSHIPS

Through public and private partnerships, the Library’s literacy-promotion efforts have a wide reach. Since its establishment by Congress in 1977, the Center for the Book in the Library of Congress is at the heart of the Library’s work for reading and literacy promotion. The center sponsors educational programs that reach readers of all ages–nationally and internationally. It provides leadership for affiliate centers for the book (including the District of Columbia and the U.S. Virgin Islands). The center also works with its 80 nonprofit reading-promotion partners–from the Academy of American Poets to the early childhood learning group “Zero to Three.

The center sponsors a number of reading-promotion contests for young people. Letters About Literature, the Library’s national reading and writing program, asks young people in grades 4 through 12 to write to an author (living or deceased) about how his or her book affected their lives. With private support, more than a million students have participated in this program over the past 20 years.

In partnership with Saint Mary’s College of California’s Center for Environmental Literacy, the Library participates in River of Words–an international poetry and art contest for youth (K-12) on the theme of the environment.

The “A Book That Shaped Me” Summer Writing Contest encourages rising 5th- and 6th-graders to reflect on a book that has made a personal impact on their lives. Administered through the summer reading programs of local public library systems in the Mid-Atlantic region, the program honors its top winners at the Library’s National Book Festival in Washington, D.C.

ONLINE RESOURCES

The Library of Congress recognizes that in the modern, media-driven world, reading online–or in any genre or format–must be at the center of its literacy-promotion efforts. To that end, the Library’s reading-promotion website, Read.gov, offers online resources ranging from booklists to interactive video games.

Photo by Shawn Miller.

The full texts of more than 50 classic books for young people are available on Read.gov. These e-books range from “Aesop’s Fables” and “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” to “Treasure Island” and “A Christmas Carol.”

“The Exquisite Corpse Adventure,” a zany story created by multiple children’s authors and illustrators, is presented on the site in an episodic fashion. “Readers to the Rescue” is a visual game set inside a library inhabited by a cast of storybook characters. Players will view as many as 36 unique animated short films and access 51 classic books they can read online. “Readers to the Rescue” is a collaborative project of the Library of Congress, Brigham Young University and the Ad Council.

The site also offers parents and educators online resources that can assist them in their reading-promotion efforts, including information about programs offered in their local area.

ACCESS FOR ALL

“That All May Read” is the credo of the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped (NLS), part of the Library of Congress since 1931. The program provides braille and “talking-book” materials–free of charge–to eligible

U.S. residents (including American citizens living in foreign countries) and lets those unable to use standard print materials due to visual impairment or physical handicap sign up through a network of local libraries. Today, program members also can download their books, magazines or music through their computers or even their cellphones.

LITERACY AWARDS

Since 2013, the Library of Congress Literacy Awards have provided monetary prizes to three organizations annually, in the U.S. and abroad, that do exemplary, replicable work alleviating the problems of illiteracy (inability to read). Annually, a “best practices” document is produced and distributed.

“Literacy opens doors to life’s great opportunities,” said philanthropist David M. Rubenstein, who supports the awards and the National Book Festival. “Literacy is the basis for success in life.”

AMBASSADORS FOR READING AND VERSE

With the Children’s Book Council and Every Child a Reader, the Library is the national cosponsor of the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, a major children’s or teens’ author who advocates for youth reading. The ambassadors, each of whom chooses a theme for his or her tenure, visit children in reading-related venues all over the nation. The current ambassador is Kate DiCamillo, whose platform is “Stories Connect Us.”

Eugene Roh and Ann Brenner work in the African and Middle Eastern Division Reading Room. Photo by Shawn Miller.

The Library’s Poetry and Literature Center promotes those arts and advises the Librarian of Congress in naming the nation’s Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry. Like the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, each Poet Laureate has a unique project or platform that promotes the reading and writing of verse. Juan Felipe Herrera, the Library’s 21st Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry and the first Hispanic poet to hold the position, begins his term in September.

A PLACE OF THEIR OWN

The Library of Congress is open for research to those over the age of 16. Younger readers have a place of their own–the Young Readers Center in the Thomas Jefferson Building. Children, their families, caregivers and teachers visiting the Library of Congress can come to the Young Readers Center to use computers and enjoy a broad selection of books on-site, participate in author talks and other special programming, and attend story times for young children. The center sponsors special appearances by popular children’s authors such as Jeff Kinney (“Diary of aWimpy Kid”), Katherine Paterson (“Bridge to Terabithia”), Lois Lowry (“The Giver”) and Octavia Spencer (“Randi Rhodes, Ninja Detective”).

September 17, 2015

Page from the Past: A Sailor’s Map Journal

(The following story, written by Center for the Book intern Maria Comé, is featured in the September/October 2015 issue of the LCM, which you can read in it’s entirety here.)

Sept. 2, 1945, marked the end of World War II, following the surrender of the Japanese to the Allied forces. Seventy years later, researchers can access the eyewitness accounts and memorabilia of those who served in the war, which have been collected by the Veterans History Project (VHP) in the Library’s American Folklife Center.

Sept. 2, 1945, marked the end of World War II, following the surrender of the Japanese to the Allied forces. Seventy years later, researchers can access the eyewitness accounts and memorabilia of those who served in the war, which have been collected by the Veterans History Project (VHP) in the Library’s American Folklife Center.

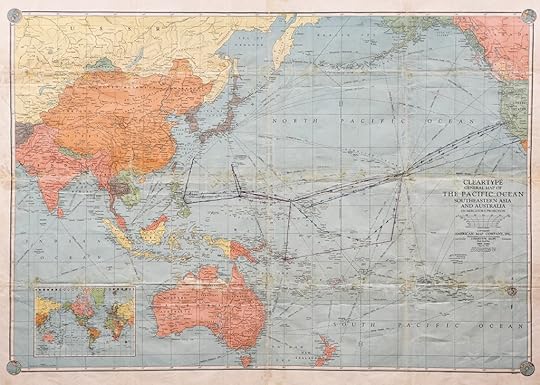

One of the more unusual acquisitions, pictured above, is a combination journal and map kept by Homer Bluford Clonts, a Navy signalman who served in the Pacific on the USS Eldorado from 1943 to 1945. Under the command of Adm. Kelly Turner, the ship and its crew helped capture the island of Iwo Jima. Were it not for the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that hastened the war’s end, Clonts and his shipmates might have been part of the U.S. mission to invade Japan, set to begin on Nov. 1, 1945.

“This is not what you’d consider a typical journal,” said VHP archivist Andrew Cassidy-Amstutz. “Clonts annotated the front of this oversized map of the Pacific Ocean with his ship’s arrivals and departures from various islands. On the reverse, he kept a detailed journal of the military encounters he and his shipmates faced. His entries illustrate the daily challenges and terrors of military deployment.”

“The Navy has lost more men here at Okinawa than the Army and Marines together,” Clonts wrote in an undated entry. “Ships have been hit every day, mostly by suicide planes.”

Journal detail of Clonts’ movements and battles from 1943-1945. Veterans History Project.

The map journal came to the Library jammed in a poster tube, covered in tape and water-stained.

Prior to extensive conservation treatment, the map was badly distorted from the tape and unusable. The paper was very fragile and more than 35 feet of adhesive tape used to repair tears in the map’s many folds had to be removed both manually and with solvents.

“This was a very challenging treatment,” said Heather Wanser in the Library’s Conservation Division, who painstakingly performed the work. “The colored inks used to print the map, and the pen ink that Clonts used, were soluble in some of the solvents that are used to remove tape and adhesive. Some of the tape was extremely tenacious.”

Following conservation treatment, the historically significant text is legible.

In September 1945, Clonts wrote, “The war is over.” His journal concludes with this entry on Nov. 10, 1945, “Discharged from U.S. Navy.”

September 16, 2015

Their Own Words, in Their Own Voices

To read a poem is a quiet joy. To read some authors’ prose is as wonderful as reading a poem. It’s just the poet, or the writer, and you. Right there, in black and white. What could be better?

How about hearing it “in color” as a poet or author reads to you from his own work, out loud?

You might get a whole different interpretation of a poem you thought you knew inside out. You might get new insight into an author, hearing that author read her work to you.

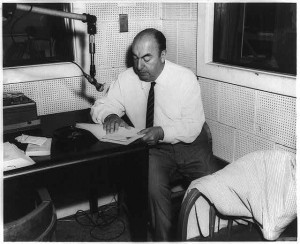

Pablo Neruda records his work in the Library’s lab

The Library of Congress, as part of 2015 Hispanic Heritage Month, is going to give you that experience this year–because it has launched a new streaming website where you can hear selections from the Library’s Archive of Hispanic Literature on Tape, audio recordings of world-famous authors and poets from the Iberian Peninsula, Latin America, the Caribbean, and U.S. Hispanics reading from their work. Most of the readings will be in Spanish, but some will be in Portuguese or other languages from places touched by Spanish or Portuguese influence.

I can still remember the first time I read Gabriel García Márquez (in the 1970s), and Octavio Paz and Pablo Neruda (in the ’80s). Their books, among my favorites, still wait for me at home. But now, I can hear them as they heard it in their own minds, as they wrote it to be heard.

Gabriel García Márquez reads an excerpt, recorded in 1977, from his novel El otoño del patriarca (The Autumn of the Patriarch); Pablo Neruda, who recorded in 1966, reads his poem “Alturas de Machu Picchu” (“Heights of Machu Picchu”). Here’s an excerpt from its Canto Xii, translated into English:

Look at me from the depths of the earth,

tiller of fields, weaver, reticent shepherd,

groom of totemic guanacos,

mason high on your treacherous scaffolding,

iceman of Andean tears,

jeweler with crushed fingers,

farmer anxious among his seedlings,

potter wasted among his clays–

bring to the cup of this new life

your ancient buried sorrows.

Show me your blood and your furrow;

say to me: here I was scourged

because a gem was dull or because the earth

failed to give up in time its tithe of corn or stone.

Gabriela Mistral reads, among her other writings, her poems “”Canción Quechua” (“Quechua Song”), and “País de la ausencia”(“Country of Absence”). She recorded these in 1950.

Octavio Paz, who recorded in 1961, reads from his books of poems Piedra de Sol (Sun Stone), Semillas para un himno (Seeds for a Hymn), Salamandra (Salamander), and ¿Águila o sol? (Eagle or Sun?). Here’s a little bit of his “Salamander:”

The salamander

a lizard

her tongue ends in a dart

her tail ends in a dart

She is unhissable She is unsayable

she rests upon hot coals

queens it over firebrands

If she carves herself in the flame

she burns her monument

Fire is her passion, her patience

There is more, much more to the Library’s celebration this year of Hispanic Heritage Month. See the website for more activities and presentations.

September 11, 2015

National Book Festival Redux

(The following article, written by Mark Hartsell, was featured in the Library of Congress staff newsletter, The Gazette.)

“I cannot live without books,” Thomas Jefferson famously once said. The 15th National Book Festival last week provided evidence that plenty of others can’t, either.

Thousands of book lovers descended on the Washington Convention Center on Saturday to see a record 170-plus authors and illustrators, pay tribute to America’s fighting men and women, explore the Jefferson legacy, meet a new poet laureate and indulge their literary passions via the first-ever festival session devoted to romance fiction.

Library Chief of Staff Robert R. Newlen opened the 12-hour literary love fest at 10 a.m. with the presentation of the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction to Louise Erdrich, author of critically acclaimed novels such as “Love Medicine” and “Plague of Doves.”

“She is, above all, an American original, a writer whose work rings with authenticity,” Newlen said.

Erdrich joins a line of literary heavyweights who’ve received a Library prize for fiction: Isabel Allende, Toni Morrison, Philip Roth, Don DeLillo and E.L. Doctorow, among others.

“I have to say, I am very surprised and moved that you came to this event because there is so much going on here,” Erdrich told a full house in the Fiction pavilion. “Thank you.”

Across the convention center, the Library’s Letters About Literature program gave one young reader face time with a favorite author.

The national reading and writing program asks students around the country to write to an author about how his or her book affected their lives. At the festival, Gabriel Ferris read his award-winning letter to Walter Isaacson, author of the best-selling “Steve Jobs,” as Isaacson listened.

“I didn’t really understand how some- one could be too determined, too driven and too rigid,” said Ferris, reading from his letter. “It was not until many chapters later that I started to realize that the same factors that played into [Jobs’] extreme success were the very factors that contributed to his personal human failure in almost all relationships. …

“Is excess a requirement for extreme success? Your story leaves me wondering if this is the case.”

Isaacson put his arm around Ferris and offered appreciation for the analysis.

“Thank you for writing the most insightful review not only of my book but of Steve Jobs’ life,” Isaacson said.

Books, Fun and Games

On the lower level of the convention center, visitors purchased books, queued up in book-signing lines that stretched across the massive exhibit-hall spaces, got a bite to eat, attended presentations at the Library of Congress Pavilion, competed at games in a virtual maze, posed their children for photos in astronaut uniforms, played impromptu volleyball with balloons and just enjoyed the company of thousands of like-minded folks.

“I am among my people #natbook- fest15,” one festivalgoer tweeted.

Among the many special programs at this year’s festival, the Library offered a five-part series exploring the impact of war on the men and women who fight.

“The Human Side of War” opened with an interview, conducted by festival co-chairman David M. Rubenstein, of journalist and “The Greatest Generation” author Tom Brokaw.

Brokaw described his experiences growing up under the World War II generation and, as a journalist six decades later, covering the men and women fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan.

He recalled meeting a husband and wife serving together in the National Guard in Iraq, while the grandparents cared for their children back home in the States.

This country probably won’t have a draft again, Brokaw said, but he wondered about the effect on society of such a lack of shared sacrifice.

“We have less than 1 percent of our population in uniform,” Brokaw said. “We’re asking them to take all the risks, to come home missing limbs, to be psychologically damaged, to come home in body bags. … It seems to me that’s immoral for a democratic society.”

A Laureate Launches

The festival also offered a poetry premiere: The public debut of Juan Felipe Herrera as U.S. poet laureate. Herrera appeared in the Children’s pavilion to discuss his recent book, “Portraits of Hispanic American Heroes,” served as a judge at the evening poetry-slam competition and announced the official project of his laureateship.

That project is La Casa de Colores, an invitation to Americans to contribute verse to an “epic poem” about the American experience. The poem, “La Familia,” will unfold monthly, with a new theme each month about an aspect of American life, values or culture.

“La Casa de Colores will be the voices of everybody,” Herrera said at an after- noon press conference. “Our voices are going to dance and sing.”

Taking Flight

That evening in the Biography pavilion, history buffs filled the floor and balcony of a cavernous ballroom to hear Pulitzer Prize winner David McCullough discuss his most recent book, “The Wright Brothers.”

“The older I get, the more I think about our story as a country,” McCullough said. “History isn’t just about politics and war. It’s about art and music and finance and medicine and invention. It’s about everything. It’s about the human mind, human achievement, human aspirations.”

McCullough assessed the brothers’ individual talents (“Wilbur was a genius; Orville was very clever and innovative”), passed on Wilbur’s secret to success (“pick out a good mother and father and grow up in Ohio”) and the brothers’ sense of their achievement (“they knew what they had done could change the world”), and offered advice to a history teacher in the audience.

Why, the teacher asked McCullough, should we study history?

“History is human,” he said. “It’s not boring, it’s not statistics, it’s not dates you have to memorize. It’s about human beings. ‘When in the course of human events’ our great document begins – and the operative word there is ‘human.’ “

As his session neared the close, McCullough stopped and turned to his interviewer with another thought: “Oh, I wish this could be longer.”

The thousands of visitors at the 15th National Book Festival surely would agree.

(In addition, the following is an excerpt from a post originally appearing on the National Book Festival blog.)

Folks couldn’t seem to get enough of the new book festival app introduced this year. We received positive feedback about how it helped people plan their day and schedule which of the author presentations to attend.

The festival presentations were taped and the videos will start to become available on the National Book Festival website in the next month or so. (There will be a blog post to let you know when.) In the meantime, if you couldn’t make the festival or would like to join me in reflecting, today’s post contains a collection of photos from Saturday’s festivities. Enjoy!

#gallery-1 {

margin: auto;

}

#gallery-1 .gallery-item {

float: left;

margin-top: 10px;

text-align: center;

width: 33%;

}

#gallery-1 img {

border: 2px solid #cfcfcf;

}

#gallery-1 .gallery-caption {

margin-left: 0;

}

/* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Junior League of Washington volunteers hold a final training session prior to the National Book Festival, September 4, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller.

National Book Festival visitors peruse hundreds of titles in the book sales area, September 5, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller.

National Book Festival visitors flow into the Walter E. Washington Convention Center, September 5, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Ned the Newshound from the Washington Post greets a young fan at the National Book Festival, September 5, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Aziz and Naseem Jan, festival regulars from Pakistan, enjoy a Scholastic craft table with their daughters during the National Book Festival, September 5, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller.

A young festivalgoer tries her hand at a ring toss at the Wells Fargo booth during the National Book Festival, September 5, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Volunteers make balloon animals for children at the National Book Festival, September 5, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Visitors inscribe a wall with what they would miss most due to illiteracy during the National Book Festival, September 5, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Festival Co-Chairman David M. Rubenstein meets with blog author Lola Pyne and children from the A Book That Shaped Me and Letters About Literature contests, September 5, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Juan Felipe Herrera makes his official debut as U.S. Poet Laureate during a press conference at the National Book Festival, September 5, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Tom Brokaw speaks as part of a presentation on “The Human Side of War” during the National Book Festival, September 5, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Author Evan Osnos speaks during the National Book Festival, September 5, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Bryan Stevenson speaks at the National Book Festival, September 5, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller

A family makes their way through the National Book Festival at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center, September 5, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Kamaria Hatcher, a first-time festival volunteer from Washington, D.C., finds a quiet reading spot following her shift at the National Book Festival, September 5, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Kosi Dunn emcees the Poetry Slam at teh National Book Festival, September 5, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Mila Cuda, a teen poet from Get Lit Los Angeles, competes at the Poetry Slam during the National Book Festival, September 5, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Buzz Aldrin speaks at the National Book Festival, September 5, 2015. Photo by Kimberly Powell.

September 8, 2015

Reintroducing Poetry 180 – A Poem a Day for High School Students

The following post, written by Peter Armenti, was originally published on the blog From the Catbird Seat: Poetry & Literature at the Library of Congress.

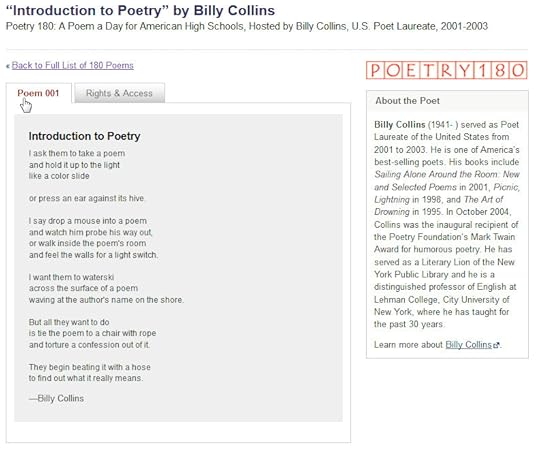

In 2001, the then U.S. Poet Laureate Billy Collins launched the online poetry project Poetry 180 as a way to introduce American high school students to contemporary poetry. Poetry 180 quickly became the most popular poetry-related resource on the Library of Congress’s website, and consistently ranks among the most visited sections of the Library’s entire site. We are quite pleased, then, to announce that Poetry 180 has received the first major redesign in its history–just in time for the start of the new school year!

Poetry 180, for those of you new to the resource, presents students with a new poem for each of the 180 days of the typical high school year. Participating schools often have the daily poem recited through the school’s public announcement system, read aloud by a teacher or student in the classroom, or printed and posted on a class’s bulletin board. The poems—all of which have been handpicked by Billy Collins–are highly accessible, and are not intended for classroom analysis. Widespread attempts by students to “torture a confession out of” a poem, as Collins writes in his own contribution to Poetry 180, “Introduction to Poetry,” are a surefire way to encourage students to dislike poetry. Poetry 180 provides examples of poems that students can enjoy, and even fall in love with, on a single reading.

In addition to a more modern look and feel, the new Poetry 180 website includes brief biographies of contributing poets, along with a “Rights & Access” tab that will take you quickly to permissions information for the selected poem.

Biographies for poets, as well as a “Rights & Access” tab, are now included on Poetry 180 poem pages. Screen capture of Poem 001, “Introduction to Poetry,” by Billy Collins

As in the past, readers can use the Subscribe button near the top of each page to receive through email a new Poetry 180 poem each weekday during the course of the school year. The first Poetry 180 poem of the school year will be sent out later this morning.

Several months ago the Library asked Billy Collins if he could comment on how he came up with the idea for Poetry 180, which was his major project as Poet Laureate, and its impact. Here is his response:

Thinking of a “project” connected with poetry did not come naturally to me. The poet part of me is happiest in his cell, writing away in private. But the energetic projects of some previous laureates set a precedent that was hard to ignore. Plus, as Poet Laureate, one has the material and human resources of the Library of Congress more or less at one’s disposal, which is a rather heady position to be in. Poetry 180 was a response to the general lack of contemporary poetry in the curriculum of American high schools. I thought that gathering together 180 good, clear poems—one for every day of the school year—and having one read each day would result in showing students that poetry was more than a subject to be studied, like psychology and physics; poetry could be an enjoyable, even stimulating part of every day life. Much to my surprise, I was right. I have gotten hundreds of responses from high school teachers all over the country telling me that Poetry 180 actually works in the classroom. It seems that just one poem can melt a student’s resistance to Poetry—if it’s the right poem. Happily, what began as a Library Congress website has turned into two poetry anthologies from Random House designed for any reader, not just students, especially those who have ignored poetry ever since they abandoned it at graduation.

We’d love to hear from those of you who are currently using, or have used, Poetry 180 in your school or classroom. How are you presenting the poems, and what has been students’ reaction? Leave a comment below!

September 4, 2015

Pinterest This: For Hire

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, monthly job gains averaged 235,000 over the last three months. Many of these jobs and industries didn’t even exist 10, 20, even 30 years ago – coder, software engineer, social media strategist, Zumba instructor, to name a few. But, just as new jobs are created, others become completely obsolete. Out with the old, as it were.

As we mark Labor Day on Monday and pay tribute to hard work and the American dream, here is a look at trades from a bygone era. You can check out the complete selection by following the Library’s new Pinterest board on jobs of the past.

While some of these professions eventually evolved into other vocations thanks to industrialization and technological advances, quite a few were dangerous and often involved child labor.

Rat catcher starting a ferret after rats. Bain News Service. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Yesterday’s rat catcher could definitely be considered today’s exterminator, who removes all manner of pests from your home, including rats. However, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, catching rats wasn’t as simple as baiting traps and using poison. Animals were often employed, including ferrets, as seen in this picture (left) from the Library’s George Grantham Bain (Bain News Service) collection.

In his book, “Full Revelations of a Professional Rat-Catcher” (1898), English rat catcher Ike Matthews wrote an account of his career catching vermin.

“When working ferrets for rat-catching, always work them unmuzzled. Make as little noise as possible, as Rats are very bad to bolt sometimes. Never grab at the ferret as it leaves the hole, nor tempt it out of the hole with a dead Rat. The best way is to let the ferret come out of its own choice, and then pick it up very quietly, for if you grab at it, it is likely to become what we call a ‘stopper'; and never on any account force a ferret to go into a hole.”

Employee entertainment is a perk in many companies today, including amenities like pool tables and foosball to happy hour and office pets. In cigar factories during the 19th and 20th centuries, lectors entertained employees by reading books or newspapers aloud. They were often paid by the workers or workers’ unions.

Child labor has existed throughout most of human history. They were exploited because of their size and manageability, getting paid less than adults and put in harm’s way. For example, young boys employed as powder monkeys were in charge of transporting and then loading gunpowder into giant guns and canons on warships.

If you’ve ever watched “Downton Abbey,” you’re probably familiar with the position of valet. This “gentleman’s gentleman” served as a personal attendant to the master of the manor, dressing him, running his bath, shaving him and, as seen in this picture, even ironing his clothes. I suppose a modern equivalent could be a personal assistant, although domestic duties usually aren’t part of the job.

Woman working at switchboard. Photo by Harris & Ewing, 1935. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

As it turns out, milkmen still exist. But, they’ve become less of a necessity and more of a convenience in today’s society, much like grocery deliveries, according to this article in the New York Times.

Other historical jobs featured on the Pinterest board include switchboard operator, typist, lamplighter and bowling pin boy.

Make sure to check out the Library’s other Pinterest boards (46 total), with topics ranging from architecture to sports and activities to other holidays and celebrations.

August 31, 2015

With Largest Cast Ever, Festival is One For the Books

(The following is an article written by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library of Congress staff newsletter, The Gazette.)

2015 National Book Festival Poster. Peter de Sève, artist.

The Library of Congress National Book Festival next weekend opens its latest chapter with a few new plots and the largest cast of characters in festival history.

The 15th annual festival will offer its biggest-ever roster of speakers, take a first fling with literary love, go back to the movies, pay tribute to America’s warriors and honor the Founding Father whose own library served as the basis for today’s Library of Congress collections.

The festival, themed “I Cannot Live Without Books,” takes place Sept. 5 at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in the District. The event opens at 10 a.m. Saturday with the presentation, to author Louise Erdrich, of the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction. Twelve hours and more than 170 speakers later, it closes with Books to Movies – the sequel to last year’s enormously popular program exploring the adaptation of literary works to the big screen.

In between, the festival presents Pulitzer Prize-winning historians (David McCullough, Rick Atkinson), poets (new U.S. Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera), best-selling mystery writers (David Baldacci, Lisa Scottoline), chefs (Patrick O’Connell of the Inn at Little Washington), weathermen (Al Roker), cartoonists (“Pearls Before Swine” creator Stephan Pastis) and one moon-walking astronaut: Buzz Aldrin, author of a new children’s book.

Special programs highlight the day and evening sessions:

In honor of the 200th anniversary of the purchase of Thomas Jefferson’s personal library by the Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division chief Mark Dimunation will host presentations by “American Sphinx” author Joseph Ellis, Annette Gordon-Reed (“The Hemingses of Monticello”), Jon Meacham (“Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power”) and Henry Wiencek (“Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves”).

“Greatest Generation” author Tom Brokaw and Pulitzer Prize-winner Atkinson are among eight authors who will explore “The Human Side of War,” a tribute to American warriors of the past 75 years. Veterans History Project Director Robert Patrick hosts the program.

Erdrich, author of critically acclaimed novels “Love Medicine” and “The Plague of Doves,” will receive the third Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction in recognition of lifetime achievement in writing fiction that explores the American experience.

A complete list of special programs is available at www.loc.gov/bookfest/information/specialprogramming.

For the second straight year, the festival will extend into the late hours – this year with poetry, movies and romance.

The festival again will stage a youth poetry slam – a competition that drew a raucous standing-room-only crowd for its 2014 festival debut. The event this year features teen poets from the District of Columbia, Los Angeles, Houston and Chicago – and a celebrity judge who knows a thing or two about poetry: Herrera, the new U.S. poet laureate.

At Books to Movies, author A. Scott Berg (“Genius”) will present a multimedia overview of the film industry, then join a panel discussion about film adaptations with Lawrence Wright (“Going Clear,” his book on Scientology) and Anne-Marie O’Connor (“The Woman in Gold”). Washington Post film critic Ann Hornaday will moderate.

The festival has an evening fling with literary love: the first program devoted to romance fiction, the second-best-selling category in the publishing business. The program features three of the genre’s best-loved writers – Sarah MacLean (“Never Judge a Lady by Her Cover”), Beverly Jenkins (“Destiny’s Captive”) and Paige Tyler (“Wolf Trouble”).

The festival again provides a showcase for its host – the Library. The Library of Congress Pavilion features exhibitions by 13 offices and 10 presentations that highlight services, collections and publications.

Those presentations explore, for example, World War I sheet music, mapping the West with Lewis and Clark, Congress.gov, the World Digital Library and Chronicling America. The complete schedule for the pavilion can be found at www.loc.gov/bookfest/lcpavilion.

The complete schedule of events, and other information about the festival, is available at www.loc.gov/bookfest/.

August 28, 2015

Inspired By a Soldier’s Story

The following was written by Matthew Camarda, one of 26 college students participating in the Knowledge Navigators program at the Library of Congress. The 10-week internship program is offered to students at the University of Virginia, Catholic University of America and the College of William & Mary. Camarda is currently a senior at the College of William and Mary, majoring in government with a minor in history. His job creating Initial Bibliographic Control records for the Library’s History and Military Section related to his own interests in American politics and history.

Welton Taylor at the EAA Air Venture Show, 2006. Welton Taylor Collection, Veterans History Project.

As a Knowledge Navigators intern, I was tasked with creating initial bibliographic control records for the History and Military Science section. This brought me into contact with hundreds of history and military books, mostly obscure, but also fascinating. What I encountered most were veterans’ autobiographies detailing their time in the armed forces.

One book in particular stuck with me: “Two Steps from Glory: A World War II Liaison Pilot Confronts Jim Crow and the Enemy in the South Pacific,” by Army Major Welton I. Taylor and his daughter, Karyn. What grabbed me were Taylor’s effective, powerful voice, his moral fortitude and an incredible life story.

Taylor’s personal narratives are also part of the Library’s Veterans History Project’s collections.

Born in 1919, Taylor spent the first five years of his life in Birmingham, Alabama. He and his family were forced to leave when his mother saw a klansman unhooded at a Ku Klux Klan rally and promptly yelled at him.

He grew up in Chicago, where he developed an interest in making and selling model airplanes. In his VHP interview, Taylor remembered his father telling him that no black men had ever been allowed to be a pilot in the Armed Forces, but that he should try anyway, saying, “Times change, things change, people change.”

Taylor attended the University of Illinois through scholarships from the black fraternity Kappa Alpha Psi, majoring in bacteriology and serving for two years in the ROTC’s Field Artillery, eventually becoming a second lieutenant (one of the first black officers at that time) just before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Serving with the Second Battalion of the 184th Field Artillery Regiment, he witnessed how even successful black units faced discrimination by the Army, who shipped away freshly trained recruits and skilled officers to labor outfits.

Beating the odds, Taylor was sent to flight school where he averaged a 98 percent in all his tests and fought to prevent the school from segregating his living quarters. In 1943, he was sent to the Pacific Theater, first to Guadalcanal and later to New Guinea and Mortai, earning seven Air Medals.

Even abroad, discrimination was rampant. In one instance, every white and black officer’s pay was docked $25 every month to pay for a new, whites-only officers’ club. Refusing to accept this, Taylor found a captain who helped him send his complaint to judge advocate general, which forced the white officers to either refund the black officers the money or allow them inside the club.

Returning home to Illinois from the war, Taylor continued to fight segregation. Recruited by the wife of Champaign’s district attorney, Taylor fought alongside black and white veterans to integrate restaurants and movie theaters.

Taylor and his wife, Jayne, later moved to the all-white neighborhood of Chatham on the South Side of Chicago. There, Taylor served in several community organizations and was even appointed to Mayor Richard M. Daley’s Commission on Human Relations. Despite the Taylors’ and other community leaders’ best efforts, white flight quickly flipped the town’s racial composition.

Welton Taylor at Guadalcanal, 1944. Welton Taylor Collection, Veterans History Project.

Taylor would go on to lead a distinguished career as a microbiologist. As an instructor at the University of Illinois’ College of Medicine, he wrote papers on the diseases that had killed soldiers during wartime – including diphtheria, tetanus and gas gangrene – proving that each could be cured by penicillin. Working as a microbiologist at Swift & Company and later at Children’s Memorial Hospital, he helped develop a new method for salmonella detection that is still used today.

Taylor also spent two decades consulting for hospitals, corporations and the Center for Disease Control, helping them address food-borne illness, Legionnaires’ Disease and AIDS. In 1985, the CDC named a newly discovered bacterium, Enterobacter taylorae, partially in his honor.

I had never heard of Taylor, yet the breadth and magnitude of his accomplishments are staggering. His skill as a pilot and a leader made a mockery of the Army’s segregation policies. Men like Taylor enabled President Truman to desegregate the Armed Forces, which was recommended by the President’s Committee on Civil Rights, currently on display in the Library’s Civil Rights exhibit.

Taylor’s life proves that you don’t have to achieve fame to make a difference; day-to-day hard work and perseverance can bring about gradual but monumental change. Further, it affirms the essential work of the Library of Congress (and the Veterans History Project), which not only compiles stories but also encourages people to tell theirs.

In recognition of the 70th anniversary of VJ-Day, the Veterans History Project has launched a major campaign to preserve the stories of World War II veterans residing in and around the nation’s capital. Select appointments are available through Sept. 2 to conduct interviews on site at the Library. In addition, training sessions for interviewers are being offered Sept. 25 and Sept. 26.

Other Resources:

“Experiencing War: African American Veterans Fighting Two Battles”

African American Odyssey: The Depression, the New Deal and World War II

Sources: “Two Steps from Glory,” by Maj. Welton I. Taylor, with Karyn J. Taylor; Welton I. Taylor Collection (Interviewer: Thomas Murray)

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers