Library of Congress's Blog, page 138

December 10, 2015

10 Stories: The End of the World! Chronicling America

In celebration of the release of the 10 millionth page of Chronicling America, our free, online searchable database of historical U.S. newspapers, the reference librarians in our Serials & Government Publications Division have selected some interesting subjects and articles from the archives. We’ve been sharing them in a series of Throwback Thursday #TBT blog posts.

Today we return to our historical newspaper archives for stories about the END OF THE WORLD! Just goes to show you, people seem to be worried about these things all the time. The big question: when?

[image error]

“Scientists predict that the comet of 1866 will strike the earth Monday and this is what will happen.” Well, there you have it. Detail from the Daily Inter Mountain of Butte, Mont., Nov. 11, 1899.

1867: “The Year of Terrors”

“Outpouring of the Vials of Wrath—Volcanoes, Earthquakes, Cyclones—Tremendous Convulsions on Earth and in the Heavens—Meteors, Comets, and Revolutions—The Islands that Flee Away, and the Mountains that are not Found—The Appalling Wonders of 1867.” And that’s just the headline! Philadelphia Evening Telegraph, Dec. 6, 1867.

1875: “The End of the World”

The Helena Weekly Herald of Nov. 18, 1875, leads with this pretty dire account, but we’re not so sure the editors buy into it, as it appears adjacent to details on how to subscribe to the paper for up to a year.

Monday, Nov. 13, 1899: “The Earth Will Come to an End Monday”

Among the most specific predictions ever, courtesy of another one of those pesky eminent Viennese scientists. Daily Inter-Mountain of Butte, Mont., Nov. 11, 1899.

1901: “What Has Happened Once Will Occur Again—The Law of Cycles”

So says the San Francisco Call of Oct. 4, 1896: “Five Years From Next December, the Sun and the Planets Will Bear about the Same Relation to the Earth as in the Year of the Great Deluge.” Well, they were off by five years, the specific plague and a degree of magnitude—but San Francisco DID get a cataclysmic earthquake and fire in 1906.

1910: “Halley’s Comet Is Already Making Trouble on Earth”

As in ancient times, the occasional astronomical anomaly can get folks worked up, as the New York Tribune scoffs on May 8, 1910. “Hysterical People Consulting Astrologers and Expecting the Worst.” Plus: “There Was Fear in Chicago…” those skittish midwesterners!

1918-ish: “Will End of World Come After the War?”

The religious writer for the Seattle Star suggests modern signs of biblical prophecies of end times following World War I, described at the time as “the War to End All Wars,” Oct. 3, 1917.

Dec. 17, 1919: “Tremendous World Catastrophe to Happen on Dec. 17?”

“Professor Porta Insists That the Peculiar Grouping of the Planets Next Month Will Produce a Gigantic Sun Spot Which Will Explode the Earth’s Volcanoes, Shake Us with Earthquakes and Bury Us with Floods, but the Government Scientists Explain Why All This Is Not Likely to Happen.” Terror and reassurance, all in one extended headline in the Washington Times, Nov. 9, 1919.

Mid-20th Century: “A Coming Cataclysm”

In the Pittsburg[h] (Pa.) Dispatch of Sept. 14, 1890, Professor Jos. Rodes Buchanan is quoted quite correctly predicting social and political upheaval (and war) in Europe within a decade, then goes on to suggest social and political revolution in the United States. He was close on the latter: there was a great deal of social change during the first two decades in the U.S., but nothing approaching “cataclysmic” revolution.

Not 1933: “When Will the World Come to an End?”

In which J.P. Cole refutes a prior assertion by J.T. Boyd that the world will be destroyed by a comet in 1933. However, Cole makes no specific predictions of his own. St. Paul (Minn.) Globe, Jan. 18, 1903.

Any Time Now: “Science Finds a Force That Could Blow Up the Earth”

A somewhat clear-eyed discussion of the “explosive power of hydrogen,” which we still hope today “is more likely to serve life than to endanger it.” Richmond Times-Dispatch, May 14, 1922.

Millions of Years Away: “End of the World”

To end on a calming note: Camille Flammarion presents a reasoned view in describing “various ways in which our Earth may cease to exist.” Take heart: our fate appears to be quite some time off. New York Tribune, April 8, 1906.

Speaking of Chronicling America, the National Endowment for the Humanities (our partner in the project) has launched a nationwide contest, challenging you to produce creative web-based projects using data pulled from the newspaper archives website. We’re looking for data visualizations, web-based tools or other innovative web-based projects using the open data found on Chronicling America. NEH will award cash prizes, and the contest closes June 15, 2016.

Launched by the Library of Congress and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) in 2007, Chronicling America provides enhanced and permanent access to historically significant newspapers published in the United States between 1836 and 1922. It is part of the National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP), a joint effort between the two agencies and partners in 40 states and territories. Start exploring the first draft of history today at chroniclingamerica.loc.gov and help us celebrate on Twitter and Facebook by sharing your findings and using the hashtags #ChronAm #10Million.

December 9, 2015

From Russia With Love: Illustrated Children’s Books in Hebrew

(The following is a post by Ann Brener, Hebraic area specialist in the Library ’s African and Middle Eastern Division.)

[image error]

“La-Sevivon” (“To the Dreidel”). Omanut Press, ca. 1921. Original poem by Zalman Shneur.

Imagine that some brightly plumed bird-of-paradise has flown in amongst your backyard warblers, and you’ll probably know how I felt upon discovering a beautifully illustrated book in the vaults of the Library of Congress. Nestled between ancient Hebrew treasures – the huge volumes of Talmud, the thickly bound Bibles, the time-worn prayer-books and commentaries – I found myself gazing down at a book open to the image you see here to the left.

What was this book? Clearly it was a very old picture book for children, which is what surprised me so greatly. Today, in Israel, Hebrew picture books get churned out by the cartloads, but this one was printed in “Moscow-Odessa” and in a style that stunned me by its avant-garde beauty and its whiff of the early 1900s. No date and no author – just a title proclaiming it to be “La-Sevivon” (“To the Dreidel”), published by Hotz’at Omanut (“Art Press”). In other words, as I was soon to discover, the volume was one of the very first picture books ever published for children in Hebrew. And the story behind its publication proved fascinating.

It all began in Moscow, in the summer of 1917. Russia was in the throes of revolution and even established presses were finding it hard to obtain supplies or even get their workers past the street battles raging just outside their doors. It was hardly the most auspicious time to be launching a new publishing venture. That it got published at all was due to one woman – Shoshana Zlatopolsky Persitz, the 24-year old founder of Omanut Press and its guiding spirit over the years to come.

Persitz was the daughter of Hillel Zlatopolsky, a sugar tycoon well known for his generous patronage of Jewish culture in early 20th-century Russia. Like her father – and indeed like many of the Jewish intelligentsia in Russia and elsewhere – Persitz was passionately committed to the revival of Hebrew as a spoken language, seeing it as the natural choice for the pioneers rebuilding the Jewish homeland in Palestine. Ever the educationalist, Persitz wanted Jewish children to acquire a love for the Hebrew language while young. Yet, to her dismay, there were no beautiful picture books in Hebrew with which to instill this love. While the children of other nations were brought up on the wonderful children’s stories illustrated by the likes of Walter Crane, Arthur Rackham and Ivan Biliben, Jewish children, as Persitz was to recall many decades later, “had no books of their own” through which to enjoy a similar experience. And thus Omanut Press was born.

It was surely no coincidence that Persitz named her new publishing house Omanut, or “Art” in Hebrew. In Russia, the “World of Art” (“Mir iskusstva”) was the leading periodical for the Russian avant-garde and by linking her own venture to this prestigious arbiter of taste, Persitz proclaimed her own commitment to the highest standards of modern art and literature.

[image error]

“The Roosters and the Fox,” by Chaim Nachman Bialik. Omanut Press, ca. 1921.

Unfortunately, the Russian Revolution soon caught up with Persitz’s best-laid plans, with the Bolsheviks nationalizing the press and taking over her equipment. A year after opening and before a single book had even been published, Omanut closed its doors in Moscow and moved to Odessa, a bustling port on the Black Sea located in the Ukraine and as yet untouched by the Revolution. Odessa was already a flourishing center of Jewish culture, home to such luminaries of Modern Hebrew literature as Mendele Mocher Sforim and Chaim Nachman Bialik. But the events of 1917 sent even more Jewish writers and artists pouring in.

With such a stable of local talent from which to draw, Odessa was to prove fertile ground indeed for Omanut. Bialik himself created the text for one of the books: a beautiful rhymed version of a medieval fox-fable. Zalman Shneur, famous novelist in Hebrew and Yiddish, wrote the poem for “To the Dreidel.” Another book was a translation by Asher Ginzberg, renowned Zionist thinker better known by his pen name Ahad ha-Am.

“To Please Everybody.” Omanut Press, ca. 1921. Russian folktale adapted by Tolstoy; translated into Hebrew by Ahad Ha-Am (Asher Ginzberg).

It was also Jewish art students at the Odessa School of Art that provided the beautiful illustrations accompanying these and half a dozen other books published by Omanut. The group of four young men in their early 20s signed collectively as “Havurat tsayarim” or “a Group of Painters” in Hebrew.

As the Bolsheviks advanced on the Ukraine, Persitz relocated again, this time to Frankfurt-am-Main in Germany. There she republished the beautiful picture books illustrated by the young art students in Odessa and also began publishing the polished Hebrew translations of world literature for children by which the press was to become famous.

In 1925, Omanut left Europe altogether, establishing itself once and for all in Tel-Aviv. Yet the end of Omanut’s odyssey was also to prove something of a beginning for Persitz, whose contributions to Jewish education were quickly recognized by the leaders of the emerging Jewish State. For years she played a key role in the Tel-Aviv Department of Education, and in 1949 she was elected to the first Knesset (“Legislative Assembly”) of the newly established State of Israel, chairing the Committee of Education and Culture.

By the time Omanut closed its doors in 1945, its books had become a staple of education for several generations of Israeli youth, introducing them to such world-class authors as Victor Hugo, Jules Verne and Lewis Carrol. The exquisite picture books, however, were apparently never reissued and remain almost completely unknown even to dedicated bibliophiles.

On Tuesday, Dec. 15, at noon, Ann Brener gives an illustrated lecture on the legacy of Shoshana Zlatopolsky Persitz, including a rare opportunity to see these and other exceptional children’s books. More information can be found here. The presentation will be taped and will later be accessible here.

December 8, 2015

Library in the News: November 2015 Edition

Willie Nelson was the talk of the town as the Library celebrated his work and career during a concert in November, as he received the Gershwin Prize for Popular Song.

“When Willie took the stage to accept the Gershwin prize, you could see the pride on his face,” wrote Brendan Kownacki for Hollywood on the Potomac. “He joked the evening was ‘a lot of great music, and I remember SOME of it.’ Kidding aside though, he declared this ‘one of the greatest things to happen to me’ and noted that a lot has happened in his 83 years.”

“Willie Nelson concerts tend to be boisterous affairs, with hippies and hillbillies dancing to the music side by side,” wrote Juli Thanki for The Tennessean. “Wednesday night’s event at the DAR Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C., a star-studded tribute to Nelson, the 2015 recipient of the Library of Congress’ Gershwin Prize for Popular Song, was a little more staid (the audience featured several members of Congress in suits and ties), but no less adoring.”

Other stories ran in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and on Associated Press TV.

Don’t miss the broadcast Jan. 15 at 9 p.m. Eastern on PBS stations.

While Nelson was being inaugurated as the seventh Gershwin Prize winner, author Kate DiCamillo was enjoying her final days as the 2014-2015 National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature.

She had this to say to The Washington Post: “When I first set out on my journey as National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature … I wanted to let people know that we can all — young and old — connect more deeply through stories. But oddly, what happened is that as I worked to deliver the message, the message was delivered to me. By that I mean that I have traveled all over the country. I have visited people gathered together in classrooms, libraries, lunchrooms, bookstores, community centers, auditoriums, gymnasiums and theaters.

“And everywhere that I have gone, people have welcomed me. They have opened themselves to me. Over and over again, I have looked up from the page I am reading and seen faces gathered together, listening.”

Celebrating its 15th anniversary this year, the Library’s Veterans History Project (VHP) was also recognized.

“Americans will pause Wednesday to remember the nation’s veterans. But one Library of Congress project is working to ensure veterans’ stories are preserved for years to come,” Bridget Bowman wrote for Roll Call.

NBC4’s special report, “Saluting Our Veterans,” provided an in-depth look at the work the project does in collecting the wartime remembrances of our nation’s veterans.

The Washington City Paper highlighted a new VHP initiative: to collect the stories of D.C.-area veterans.

“A number of reasons may explain why D.C.-area vets are underrepresented in the Library’s archives,” wrote Andrew Giambrone. “(Andrew) Huber says the project has historically relied on word-of-mouth and its partner organizations to reach veterans; additionally, many veterans in D.C. area (especially affluent ones) may not take advantage of local services that function as access points for the VHP.”

The Veterans History Project is part of the Library’s American Folklife Center. In addition to collecting stories of the nation’s veterans, the center also partners with StoryCorps, whose oral interviews are archived at the Library. This Thanksgiving, StoryCorps introduced “The Great Thanksgiving Listen,” inviting any child to record an interview with a grandparent or another elder using a free StoryCorps app.

“‘There are certain things we don’t talk about, and don’t ask’ in ordinary conversation. But knowing people may listen to this generations from now, he (StoryCorp Founder Dave Isay) says, means we ‘talk about things you don’t usually,’” reported KJ Dell’Antonia for The New York Times. “‘Ask ‘is there anything that you want to tell me now that you’ve never told me before?’ Often these really surprising and wonderful things happen.’”

Other stories ran on Mashable, Huffington Post and USA Today.

December 3, 2015

Going to Extremes: The Greatest Wedding Cake on Earth?

(The following is an article written by Audrey Fischer, managing editor of the Library of Congress Magazine, and featured in the November/December 2015 issue. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

The Library’s food collections include once-edible artifacts.

Minnie Maddern Fiske and her husband, theater manager Harrison Grey Fiske. Tom Thumb’s widow sent the cake to Harrison Fiske in 1905, perhaps hoping that it would lead to stage work or some publicity for her autobiography published the following year. At the time, Fiske was editor of “The New York Dramatic Mirror.”

Minnie Maddern Fiske and her husband, theater manager Harrison Grey Fiske. Tom Thumb’s widow sent the cake to Harrison Fiske in 1905, perhaps hoping that it would lead to stage work or some publicity for her autobiography published the following year. At the time, Fiske was editor of “The New York Dramatic Mirror.”“The public are under the impression that I am not living,” she noted in her letter to Fiske, which accompanied the slice of cake. In 1885 she married Count Primo Magri—two inches shorter than her first husband. To support their lavish lifestyle, the couple continued to perform into their later years.

Recent “food finds” in the Library’s collections include a hand-made greeting card decorated with rice sent to civil rights activist Rosa Parks by her nephew and a candy conversation heart from the 1920s in the Coolidge-Pollard Families Papers—a collection related to the maternal side of President Calvin Coolidge’s family.

December 1, 2015

Looking Back on the Bus Boycott

(The following post is by Jeanne Theoharis, distinguished professor of political science at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York and the author of the award-winning “The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks.” A revised edition of the book has just been published with a new introduction drawn from the recently opened papers at the Library of Congress.)

“We are having a difficult time here, but we are not discouraged. The increased pressure seems to strengthen us for the next blow.”

–Rosa Parks writing a colleague during the Montgomery bus boycott

Rosa Parks waving from a United Air Lines jetway in Seattle, Washington. Photograph by Gil Baker, 1956. Rosa Parks Papers, Library of Congress.

Sixty years ago, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus. Her decision lead to a yearlong bus boycott and galvanized a new chapter of the modern black freedom struggle. But too often it ends there. In our public imagination of the boycott, she kicks it off and then fades into the background. The movement just seems to happen.

The problem with this story is that it backgrounds all the work – the organizing, the building, the fundraising and traveling – that laid the ground work for that moment to turn into a movement and the effort that kept it going for a year. It turns the Montgomery bus boycott into an obvious event that was destined to succeed, rather than one created by the visions, efforts and continued steadfastness of ordinary people.

What transformed Rosa Parks’ courageous refusal into a movement was a group of seasoned activists in place in Montgomery and a community that united in struggle. Rosa Parks was one of those seasoned activists. Yet the crucial part she played in the boycott’s continuation, not simply as its spark, has not been widely acknowledged. The new collection of Rosa Parks’ papers and photographs that opened at the Library of Congress last February demonstrates vividly the significant role Rosa Parks played not just in catalyzing but in laying the groundwork and maintaining the yearlong bus boycott.

Parks’ papers had languished out-of-sight for nearly a decade following her death in 2005, because of a dispute over her estate. In fall 2014 the Howard Buffett Foundation bought the papers and entrusted them to the Library of Congress as a 10-year loan. These newly opened papers confirm her “life history of being rebellious,” as she put it – that began decades before her bus stand and continued for decades after. While many across the country will be marking the 60th anniversary of the Montgomery bus boycott and Rosa Parks’ galvanizing act, this essay quotes from speech notes, letters and other personal writings found in the Library’s collection to frame the story through her own words.

For more than a decade before her bus stand, Rosa Parks worked alongside union activist E.D. Nixon to transform Montgomery’s NAACP into a more activist chapter – “getting registered to vote, examin[ing] cases of police brutality, rape, murder, countless others.” She found it demoralizing, if understandable, that in the decade before the boycott “the masses seemed not to put forth too much effort to struggle against the status quo,” and she noted how those who challenged the racial order like she did were labeled “radicals, sore heads, agitators, trouble makers.”

Parks understood that her refusal to give up her seat meant she might “be manhandled but I was willing to take the chance. … I suppose when you live this experience…getting arrested doesn’t seem so bad.” Though the rightness of her actions may seem self-evident today, at the time, those who challenged segregation were often treated as “troublemakers” by many white people and some black people. Her writings show how she struggled with feeling “desolate” and crazy, even amidst other sympathetic individuals. “Such a good job of brain washing was done on the Negro,” Parks observed, “that a militant Negro was almost a freak of nature to them, many times ridiculed by others of his own group.”

[image error]

Rosa and Raymond Parks, seated at a banquet table (left side, third and fourth chair), likely at an NAACP branch meeting, Montgomery, Alabama, circa 1947. Photographer not identified.

Her surprise and delight at the movement that followed her refusal to give up her seat on the bus on Dec. 1, 1955, comes through clearly, calling the community’s reaction to her arrest “startling” in a letter to a friend. In speeches, she noted the power of organized protest on the participants themselves “We surprised the world and ourselves at the success of the protest.”

Rosa Parks lost her job five weeks after her arrest, as did her husband, and they struggled economically for many years. Despite her family’s own imperiled situation, Rosa Parks spent much of the boycott year on the road raising attention and funds for the movement back home. As she told a Pittsburgh audience in 1957, the “2 block bus ride of Dec. 1 has taken me to many places.” Going from Seattle to Los Angeles, from New York to Baltimore to Chicago to Indianapolis, by bus, car, train and plane, she brought news of the boycott across the country, turning a local struggle into a national one. Photos, datebooks, programs and speech notes found in the collection reveal her key role in raising attention and funds for the movement back home. White lawyer Clifford Durr referred to her as one of the Montgomery Improvement Association’s best fundraisers. According to news reports, she spoke “brilliantly” to audiences, while in letters home she wrote about how heady yet tiring her experiences were.

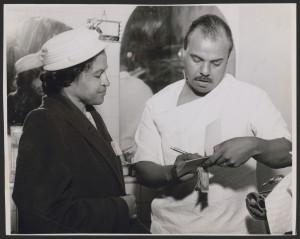

Rosa Parks collecting NAACP membership dues of $2.00, likely during her trip to Los Angeles, California, in 1956. Photograph by McLain’s Photo Service. Rosa Parks Papers, Library of Congress.

For one month, Parks also served as a dispatcher in the car pool created to sustain the year-long boycott. Police and local whites constantly harassed the car pool. Attempting to break the boycott, the city indicted 89 boycott leaders (including Parks) in February 1956. But people kept going. The boycott is “more than successful,” Parks wrote, “in spite of all the obstacles placed against us.” Her faith sustained her. “I do not feel alone, God is with me,” she told a reporter.

Rosa Parks saw the point of the protest as larger than a seat on the bus but dismantling a system of oppression. On the back of a program the day the Supreme Court declared Montgomery’s bus segregation unconstitutional, her speech notes read “happy to hear of it,” but there was “more work to be done.” Despite the boycott’s successful end, the Parkses still continued to receive death threats and couldn’t find steady work. Eight months later, they left Montgomery for Detroit, where her brother lived. There, Rosa Parks would remain active in the struggle for justice in Detroit and across the country for the next half a century.

Looking at Rosa Parks’ actions during the boycott demonstrates vividly there was nothing predestined about its success. People chose, amidst threats to their person and their livelihood, to take repeated action to make it happen. But the version we are often taught turns it into a museum piece to be admired, the gold standard of American protest now mistakenly used to diminish contemporary movements like Black Lives Matter. By reading Rosa Parks’ papers, we see the effort and sacrifice the boycott took and the lessons and parallels it offers to struggles for justice today.

Selected items from the Rosa Parks collection will be accessible online in the early months of 2016. A few resources are currently available as part of this primary source gallery for teachers.

November 25, 2015

A Friendly Feast

Family at dinner table, Thanksgiving, by artist Edward Penfield for Collier’s Weekly. Nov. 25, 1901. Prints and Photographs Division.

This Thanksgiving, I’ll be celebrating “Friendsgiving” – a thankful gathering for those of us unable to spend the holiday with our families. The veritable smorgasbord of dishes everyone is bringing got me thinking about everyone’s food traditions, since Turkey Day usually revolves around sharing a meal. I imagine my friends’ dishes come from old family recipes or include eats that are a staple at their home celebrations.

I’ll be missing my mom’s oyster dressing this year, but I’ll be channeling my Southern roots with a big pot of slow-cooked collard greens.

Although early Thanksgiving days were spontaneous celebrations, by the mid-19th century an annual fall Thanksgiving meal was customary throughout much of the nation. During the gold rush, miners far from home observed a day of thanks. On Dec. 1, 1850, Alfred T. Jackson of Litchfield County, Connecticut, describes his California Thanksgiving.

“All we did was to lay off and eat quail stew and dried apple pie. I thought a lot about the old folks and would like to have been home with them, and I guess I will be next year…”

Ralph Lifshitz, a poultry purveyor in 1939 New York, talks about his work and customers, with sentiments that can resonate even today.

“This past Thanksgiving – not a Jewish holiday, of course – but I believe more Jews bought turkeys than ever before. Why? In my opinion, it’s due to particular world relations at this time, to conditions of oppression abroad and the desire to give thanks for living in America.”

Mr. T.L. Crouch, a Rogerine Quaker, preparing to carve the Thanksgiving turkey. Photo by Jack Delano, Nov. 1940. Prints and Photographs Division.

Holiday meals on the plantation were “nothing to get very much excited over,” according to Mrs. C.G. Richardson, who grew up during the Civil War.

“There was always extra preparation made in the kitchen, although there was always so much food on the plantation. Turkey was not just a treat for Christmas and Thanksgiving then, for instance, for there were droves of turkeys on the Brunson plantation and they were eaten whenever anybody felt like having turkey.”

Much like “Friendsgiving,” Thanksgiving celebrations weren’t always just a family affair.

The Jan. 20, 1855, issue of the North-Western Democrat (Minneapolis), featured a letter from an enthusiastic Minnesotan, who was grateful for Minnesota hospitality and Minnesota climate.

“Rarely does it fall to the lot of a traveler, when far from home and among strangers, to have an invitation to attend the welcome anniversary of Thanksgiving among a large circle of friends; but such has been my happiness. … There were present on this occasion from 80 to 90 of the most healthy, intelligent and enterprising people I ever met with … Large plates of roast venison of the finest quality first met my eye, and in close proximity were several of the squealing, bristling tribe, stretched at full length and stuffed with condiments that pamper the appetites of the most dainty. Next came the pheasant and chicken pies, with grouse, and the more honored of the feathered tribe, served up in every variety of style. The more common dishes, beef and pork, I need not mention. I came near losing myself in the countless variety of pastry of every description …”

Thanksgiving dinner at the house of Earle Landis. Photo by Marjory Collins, Nov. 1942. Prints and Photographs Division.

Frank G. O’Brien recalls a Thanksgiving gathering in Maine during the mid-19th century.

“The big clock that stood like a sentinel in the corner and reached from the floor almost to the ceiling, indicated that the time was only 10:30 when the guests began to arrive. They all came in sleighs, as the winters in those days were not trifling, but meant business from November to March. … Every crack and crevice in the house was penetrated with the aroma of roast turkey and goose, boiled onions, and a medley of other edibles … At precisely a quarter to three, the horn was blown, as the signal for all to proceed to the dining room, where long tables were groaning under their heavy loads, temptingly arranged for the nearly-starved assembly.”

In the Nov. 24, 1901, issue of The San Francisco Call writer Emma Paddock Telford recounts a suburban town’s Friendsgiving from a couple of years prior.

“At the old homestead where the dinner was served the turkey was roasted, the vegetables cooked and the coffee made. One housekeeper whose bread and pastry had achieved more than a local reputation brought the wheaten loaves, the golden pumpkin pies and the flaky cranberry tarts to grace the feast. A second furnished a big pan of luscious scalloped oysters, with crispy ringed celery and home-made jelly. A third, who had inherited her gift for dainty cookery from a line of famous Dutch hausfraus, brought a delectable salad, a store of wondrous home-made pickles and cakes that would melt in your mouth, while a fourth – a bachelor maid – supplied the fragrant coffee and the salted almonds. Home-made bonbons and artistic menus and name cards were the gift of another, while all brought happy faces, contented hearts and a store of overflowing good humor, that made the co-operative dinner a function long to be pleasantly remembered.”

How will you be celebrating Thanksgiving?

November 24, 2015

Trending: Food, Glorious Food

(The following is an article written by Alison Kelly, science librarian and culinary specialist in the Library’s Science, Technology and Business Division, for the November/December 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

Today’s popular food blogs are an outgrowth of recipe-sharing in America that began with community cookbooks.

It seems as if everyone is focused on food. We tune in to cooking shows on television and radio, read magazines and books devoted to food, even plan vacations to include food tourism. Millions share recipes and cooking tips on social media. There are myriad food blogs—on every topic from feeding your toddler to government food policy—and countless boards on Pinterest are devoted to food. We share photos of our latest meal on Instagram.

But 150 years ago, long before this virtual community of recipe-posting existed, people shared their recipes through a different medium— the community cookbook. Like blogs and Pinterest boards, community cookbooks offer an assembled collection of recipes and household hints.

The Library’s rich collection of community cookbooks documents the lives of individuals and their cooking and eating habits as American food systems were transformed by industrialization and urbanization, immigration and westward expansion. They reveal regional tastes, from recipes for peanut soup and chess pie in the south to finnan haddie and cranberry pie in New England. They trace the impact of immigration through ethnic food recipes. They demonstrate the blending of cultures through new dishes, making the description of America as a “melting pot” both figurative and literal.

Largely an American invention, community cookbooks were—and still are—often published to raise funds for causes. They were first sold during the Civil War at the great sanitary fairs held in cities across the northern states to raise money for wounded soldiers and their families. The first known example of the genre—“The Poetical Cook-Book” by Maria J. Moss—was sold at the Great Central Fair in Philadelphia in June 1864.

Community cookbooks continued to be published in ever-increasing numbers at the turn of the 20th century by church groups, improvement associations and women’s clubs. As women began attending colleges and joining clubs, community cookbooks were a tool to support their involvement not only in local projects, but in larger social causes such as the temperance and suffrage movements. By the close of World War I, more than 5,000 charitable cookbooks had been published in support of various causes.

The 20th century brought thousands of additional titles. In 1927, the bipartisan Congressional Club issued its first cookbook, containing family recipes of Members of Congress, Supreme Court Justices and other government officials. Thirteen editions followed, with recipes ranging from Bess Truman’s “Ozark Pudding” to Mrs. Thurgood Marshall’s “Deluxe Mango Bread.” Recipes, photographs and tips on Washington protocol reveal the social and political values of each period. Many editions contain a “Men Only” chapter where recipes contributed by men (rather than their spouses) appear. There, one can find Richard Nixon’s “Meat Loaf ” and Justice William O. Douglas’ “Trout” (to be cooked outdoors).

The Library of Congress Cooking Club issued cookbooks in 1975 and 1987, featuring recipes from Library staff members. From “Javanese Banana Pancakes” to “Vegetarian Chopped Liver,” the recipes are quite eclectic. A recipe for “Dandelion Wine” warns, “Do not fit on a tight, unvented cap or you will create a bomb!”

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, family treasures were lost, including cherished recipes. One local newspaper responded by becoming a clearinghouse for recipe swapping. The result was “Cooking Up a Storm: Recipes Lost and Found from The Times-Picayune of New Orleans” (2008), which not only includes the recipes but the history behind them. The compilation tells the story of a community struggling to rebuild everything—including its culinary history.

The Library’s collection of community cookbooks includes “California Recipe Book,” 1872; “Cloud City Cook-Book,” 1889; “Youngstown Cook Book,” 1905, and “The Congressional Club Cook Book,” 1965. General Collections.

November 23, 2015

Library Bestows Gershwin Prize on Willie Nelson

(The following story was written by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library of Congress staff newsletter, The Gazette.)

Acting Librarian David Mao presents the Gershwin Prize to Willie Nelson.

Whenever Willie Nelson’s bus rolls into town, actor and host Don Johnson said, you know you’re in for a good time, a big party. Wednesday night at DAR Constitution Hall was no exception.

The Library of Congress awarded its Gershwin Prize for Popular Song to Nelson on Wednesday with a musical party featuring more than a dozen of Nelson’s buddies performing some of his best-known and best-loved tunes.

“The Gershwin award is one of the greatest things that’s happened to me in my life – and a lot of things happen in 82 years,” Nelson told the audience. “This is one of the best for sure, and I really do appreciate it.”

Neil Young

In a career spanning more than 50 years, Nelson wrote country-music classics, reshaped the genre through the “outlaw” movement, produced more than 60 country and pop hits, acted in films and on television and, along the way, became a big star – a bearded, braided American icon sporting a bandana and playing a beat-up, autograph-covered guitar named Trigger.

The Library’s celebration of Nelson’s legacy began Tuesday in the Jefferson Building. Nelson attended a luncheon in the Members Room, heard the LC Chorale perform “Crazy,” snapped a group selfie with his family in the Main Reading Room, viewed treasures in the Whittall Pavilion and picked up Burl Ives’ guitar from the display and ripped out a ditty.

Host Don Johnson

On Wednesday, the party moved to Constitution Hall, where musicians Neil Young, Paul Simon, Edie Brickell, Rosanne Cash, Alison Krauss, Jamey Johnson, Leon Bridges, Raul Malo, Ana Gabriel, Buckwheat Zydeco, Cyndi Lauper and Willie’s sons Lukas and Micah Nelson performed some of his greatest hits.

Young, wearing a long fringed coat and backed by a band that featured Lukas and Micah on guitars, kicked off the program with a two-fer of Nelson favorites: “Whiskey River” and “Stay All Night (Stay a Little Longer),” a tune first popularized by one of Nelson’s own musical influences, Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys.

Following the performance by Young, Johnson took the stage, welcomed the audience and surveyed the members of Congress in the seats.

“Leave it to Willie – only he can bring together Republicans and Democrats. You may have to stay here in Washington, Willie,” Johnson said to laughter. “A whole gang of Willie’s good buddies will be here serenading him. So, Willie, sit back, relax and enjoy the show. God knows, you’ve earned it.”

Paul Simon and Edie Brickell

Bridges then delivered a slow-rolling version of “Funny How Time Slips Away,” the first in a string of Nelson classics: “Crazy” (Malo), “Remember Me” (Simon and Brickell), “Pancho and Lefty” (Cash), “Georgia on My Mind” (Johnson), “Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground” (Krauss), “Seven Spanish Angels” (Krauss and Johnson), a Spanish-language rendition of “I Never Cared for You” (Gabriel) and “Man with the Blues” (Simon and Buckwheat Zydeco).

After Simon and Buckwheat Zydeco exited, Nelson entered, accompanied by Acting Librarian of Congress David Mao, Sen. Richard Durbin, House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy, House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi and Reps. Steny Hoyer, Candice Miller and Gregg Harper, vice chairman of the Joint Committee on the Library of Congress.

“For more than five decades, Willie Nelson has inspired new generations of songwriters with his melodies, harmonies, voice and heart,” Mao said. “Tonight, we recognize this son of Texas for his matchless contributions to the musical legacy of our nation and for the world.”

Buckwheat Zydeco

With that, Nelson strapped on Trigger and embarked on a brief set of his own: “Night Life,” “Living in the Promiseland” and, with Lauper as a duet partner, a cover of the Gershwins’ classic “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off.”

Not everything went to script: After Lauper exited the stage, Nelson was informed that a malfunction in the broadcast truck necessitated that they, rather than call the whole thing off, do the whole thing over.

“We had a problem in the truck, and we need to do that one again. Is that cool?” he asked to cheers.

Lauper returned, and she and Nelson made a second go-round with the Gershwins’ musical disagreement: She said potato, he said potahto, she said tomato, he said tomahto.

Nelson closed the show with a performance of his signature tune, inviting all the cast and the audience to sing along to “On the Road Again” – a few fans went him one better and danced in the aisle.

Afterward, the man who once wrote “turn out the lights, the party’s over” approached the mic with an idea to keep the party going.

Willie Nelson and Cyndi Lauper

“We had a little trouble in the truck,” Nelson quipped. “We’re gonna do it all over again.”

The audience surely wouldn’t have minded.

The Gershwin Prize concert honoring Willie Nelson is scheduled to be broadcast on Jan. 15 on PBS.

*All photos by Shawn Miller

Gershwin Prize Sponsors

Major funding for the event was provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, PBS and public television viewers. Additional funding was provided by The Ira and Leonore Gershwin Fund, The Leonore S. Gershwin Trust for the benefit of the Library of Congress Trust Fund Board and the Library of Congress James Madison Council.

November 20, 2015

A Legacy of Librarians

A drawing of the Library of Congress, Smithmeyer & Pelz Architects, ca. 1896. Prints and Photographs Division.

(The following story, written by Center for the Book Director John Y. Cole, is featured in the November/December 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

Thirteen Librarians of Congress helped shape a legislative, national and international library.

Today the Library of Congress is truly a national library that serves the research needs of the U.S. Congress, other federal agencies in all branches of government, the American public and the global community. But that broad mission was not always apparent or supported. The dual nature of the Library of Congress—a legislative library and a national institution—was often debated by legislators and Librarians of Congress, especially during the institution’s first years.

The Early Years

The Library of Congress was established as a legislative branch agency of the American government by an act of Congress, signed into law by President John Adams on April 24, 1800. Its primary purpose was, and remains, reference and research service for Congress.

Congress established the position of Librarian of Congress with oversight from Congress’ Joint Committee on the Library. The Librarian was to be appointed by the President of the United States. The duties of the Librarian were delegated to the Clerk of the House of Representatives.

In 1802, President Thomas Jefferson asked House Clerk John James Beckley to serve as the first Librarian of Congress. Beckley assisted the Joint Committee in ordering books and publishing the Library’s first printed catalog of its holdings. Jefferson took a keen interest in the Library and frequently provided advice regarding purchases.

After Beckley’s death in 1807, Jefferson named the new House clerk, Patrick Magruder, as the second Librarian of Congress. Magruder, a Maryland lawyer and politician, was held responsible by Congress for failing to protect the Library and its financial records when the British burned the Capitol, which housed the congressional library, on Aug. 24, 1814. He resigned on Jan. 28, 1815.

The acquisition by Congress of Jefferson’s personal library in 1815 widened the scope and doubled the size of the Library’s collection, prompting President James Madison to name the first full-time Librarian of Congress. George Watterston, a local novelist and poet, was an ardent nationalist who felt that Jefferson’s library was “a most admirable substratum for a National Library.” He proposed a separate building for the Library of Congress since the United States, in his view, should have a library “equal in grandeur to the wealth, the taste, and the science of the nation.”

Congress did not share his view. Most Members of Congress felt its library should solely serve its legislative needs. The heated debate over the purchase of Jefferson’s library—which included books on many subjects and in several languages—revived old arguments against spending sparse government dollars to create a national library of cultural treasures in the European tradition. The 1815 expenditure of nearly $24,000 for Jefferson’s library of approximately 6,500 volumes also was a convenient excuse for limiting future appropriations for the Library.

Watterston’s librarianship came to an abrupt end in 1829 when newly elected President Andrew Jackson, a Democrat, replaced him with another Democrat: John Silva Meehan, a local printer and publisher. Any move toward creating a national library would be hampered by the growing rivalry between the North and South that would culminate with a bloody civil war. Moreover, Senator James A. Pearce of Maryland, who headed the Joint Committee on the Library from 1845 until his death in 1862, felt the Library of Congress should focus on its legislative responsibilities. This, coupled with a disastrous Christmas Eve fire in 1851 that destroyed two- thirds of the congressional library’s collection of 55,000 items, slowed the Library’s development and growth.

Nonetheless, Congress voted to replace the books and to build a new fireproof room for its library in the U.S. Capitol. The elegant new room opened on Aug. 23, 1853. Librarian of Congress Meehan continued to fulfill the wishes of Senator Pearce with regard to Library acquisitions and functions. As a result, the institution’s role in national functions continued to diminish.

On March 8, 1861, Sen. Pearce informed newly elected President Abraham Lincoln that the president “has always deferred to the wishes of Congress” regarding the appointment of the Librarian of Congress, and that the Joint Committee wished to retain Librarian Meehan. Lincoln ignored Pearce and on May 24 appointed a political supporter, John G. Stephenson, a physician from Terre Haute, Indiana, to become the fifth Librarian of Congress.

Stephenson spent less time supervising the Library than he did serving as a physician for the Union Army. He could do so because in September 1861, he had hired Cincinnati bookseller and journalist Ainsworth Rand Spofford as his assistant. For all practical purposes, Spofford ran the Library until Stephenson’s resignation in December 1864. Lincoln promptly appointed Spofford as Librarian of Congress.

The Modern Librarians

Spofford brought the Library of Congress into the modern age. In a post- Civil War period of growing cultural nationalism, he transformed the Library of Congress into an institution of national significance. He demonstrated to Congress that its library could serve simultaneously as both a parliamentary library and a national library. With full support of the Joint Committee on the Library, he expanded the Library’s space in the Capitol; centralized U.S. copyright registration and deposit at the Library in order to rapidly develop comprehensive collections of Americana; and promoted the authorization and construction of the Library’s first separate building. The “book palace of the American people,” known today as the Library’s Thomas Jefferson building, opened its doors in November 1897.

On July 1, 1897, President William McKinley appointed a new Librarian of Congress to supervise the Library’s move from the Capitol to the new building and to implement a major reorganization including a separate copyright department. John Russell Young, who served until his death on Jan. 17, 1899, was a journalist and former diplomat. A skilled administrator, Young worked hard to build the collections and expand the scope of services provided to Congress. He began the process of reclassifying the Library’s collection and compiling bibliographies specifically for the use of Congress. He also inaugurated the Library’s first services for the blind.

Following Young’s death, President McKinley appointed Herbert Putnam, director of the Boston Public Library, the first experienced librarian to hold the post. Putnam believed that a true national library should serve the cataloging and bibliographic needs of other libraries.

By 1901, the Library of Congress was the first American library to house 1 million volumes and that year published the first volume of a new classification scheme, based on its holdings. The Library also began printing and selling its catalog cards to other libraries. In announcing the card distribution service, Putnam said, “American instinct and habit revolt against multiplication of brain effort and outlay where a multiplication of results can be achieved by machinery.”

During his 40-year tenure, Putnam made American libraries an important Library of Congress constituency; planned and built the Library’s Annex (now the John Adams building), which opened to the public in 1939; and undertook a new international role for the institution through the acquisition of materials from other countries. Under Putnam, the Library established a Legislative Reference Service in 1914 to expand services to Congress. Early in his tenure, Putnam had courted the support of President Theodore Roosevelt who, in his first annual message to Congress on Dec. 3, 1901, called the Library of Congress “the one national library.” When Putnam retired in 1939, the Library had a staff of 1,100, a book collection of six million volumes, and an annual appropriation of approximately $3 million.

The role of libraries in a modern democracy captured the imagination of Putnam’s successor, writer and poet Archibald MacLeish. Appointed by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, MacLeish served as Librarian during wartime while presiding over a major administrative reorganization. MacLeish developed explicit statements of the Library’s objectives along with “Canons of Selection” for its collections. In addition to serving Congress, MacLeish believed that the Library should be a “reference library of the people.”

MacLeish resigned in 1944 to become assistant secretary of state. His assistant, Luther Evans, was nominated by President Harry Truman the following year. Evans was a political scientist who had been involved in the Library’s reorganization. Like MacLeish, he assessed the role and collections of the Library “for the post-war era” and urged the expansion of the Library’s national and international roles. Evans resigned in 1953 to become the third director-general of UNESCO.

The next year, President Dwight Eisenhower nominated L. Quincy Mumford, director of the Cleveland Public Library and president-elect of the American Library Association, as the next Librarian of Congress. During his 20-year term, Mumford presided over an unparalleled period of expansion. The book collections grew from 10 to 16 million volumes, the staff more than tripled and the annual appropriation multiplied from $10 million to more than $100 million.

Under Mumford, both legislative and national services were strengthened, particularly services to the library community. A report commissioned by the Joint Committee on the Library in 1962 urged further expansion of the Library’s national activities. The Library also expanded its foreign holdings, which were identified as weak during World War II. Developments in library automation during the 1960s allowed the library to distribute its cataloging data in machine readable form. The Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970, which created the Congressional Research Service, underscored the Library’s priority to serve legislators, but did not preclude its growing national and international activities.

In 1975, President Gerald Ford nominated historian Daniel J. Boorstin as the 12th Librarian of Congress. Boorstin presided over the construction and move into a third building on Capitol Hill (the James Madison Memorial Building), which opened in 1980. He focused on strengthening the Library’s ties with Congress and developing new relationships with scholars, publishers, authors, booklovers, cultural leaders and the business community. With congressional support, Boorstin created the American Folklife Center in 1976 and the Center for the Book the following year—two educational outreach endeavors that continue to flourish today.

Appointed by President Ronald Reagan as the 13th Librarian of Congress, historian James H. Billington began his tenure in September 1987 by stating his intention to leverage the new digital technologies to make the collections universally accessible in the 21st century. Making good on that promise during his tenure broadened the Library’s role to a global information resource.

MORE INFORMATION

November 18, 2015

Rare Book of the Month: A Suffragist “In the Kitchen”

(The following is a guest blog post written by Elizabeth Gettins, Library of Congress digital library specialist.)

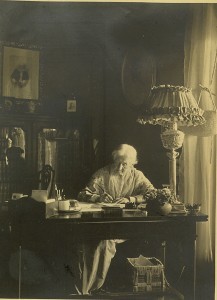

Elizabeth Smith Miller, from the Smith Miller NAWSA Scrapbooks.

It’s the time of year when one’s thoughts turn to hearth and home in preparation for Thanksgiving. In honor of this quintessential American holiday, by Elizabeth Smith Miller, is the Rare Book of the Month.

Published in Boston by Lee and Shepard in 1875, this book was written by a suffragist who believed that women’s work in the kitchen should not be given short shrift. In fact, she felt that the proper practice of domestic duties were responsible for keeping Americans civilized.

Smith Miller (1822-1911) had the fortune of being born into a well-established New York family. She was the daughter of noted politician and abolitionist Gerrit Smith, and her cousin was none other than Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It is interesting to note that aside from her cookbook, the Rare Book and Special Collections Division holds seven scrapbooks that chronicle Smith Miller’s efforts to secure women’s right to vote. Leafing through these unique one-of-a-kind scrapbooks gives a fascinating glimpse into a slice of time in American history, as well as show that Smith Miller was a woman of industry and approached life with a sense of purpose.

“In the Kitchen” opens with advice regarding how one should conduct their household through meals and entertainment. Standards were to be established and observed as the running of this important duty was seen to have a direct effect on the conduct of all family members.

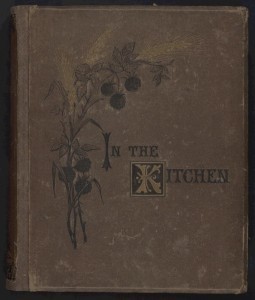

Book cover of “In the Kitchen.”

Smith Miller writes, “No silent educator in the household has higher rank than the table. Surrounded three times a day by the family, who gather from their various callings and duties, eager for refreshment of the body and spirit, its impressions sink deep, and its influences for good and ill form no mean part of the warp and woof of our lives. … Should it not, therefore, be one of our highest aims to bring our table to perfection in every particular?”

Certainly, Smith Miller held strong convictions about the importance food and dining!

“In the Kitchen” contains more than 500 pages of recipes culled from French, German, English and American collections and is part of the 4,000 volume gastronomic Katherine Golden Bitting Collection. Incidentally, included is a , which may just come in handy for cooks out there still looking for a way to prepare their Thanksgiving bird.

This Thanksgiving season, let us be thankful for those who came before us, securing American women with the right to vote as well as teaching us the importance of a well-run household.

Rare Book and Special Collection Resources

My Cookery Books: A narrative bibliography by Elizabeth Robins Pennell

Pinterest board based on images from the Katherine Golden Bitting and the Pennell Collection from the Rare Book and Special Collections Division: Art of Good Eating

Join us next month for a look into another historical volume from the Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division .

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers