Library of Congress's Blog, page 134

March 9, 2016

Inquiring Minds: Straight From the Sports Section

Sam Farber. Courtesy of ESPN.

The collections of the Library of Congress serve scholars and researchers in countless ways. Manuscripts, photographs and other ephemera documenting American culture and heritage have been inspiration for a variety of scholarship, books, programming and other projects. So, it’s always interesting to learn about those using the institution’s resources in intriguing manners. One doesn’t necessarily equate sports statistics with the Library, but a researcher has found opportunity to do just that.

Sam Farber, senior researcher at ESPN, has been using the Library’s historical newspaper collection to gather information for his work in the Stats & Information group primarily on SportsCenter and College Basketball GameDay. Thanks to a point in the right direction by a family friend who also works at the Library, Farber was introduced to the many possibilities the Library offers.

“Most of what I needed was dates on which old basketball games were played,” he explained. “That sounds pretty boring, but with those we were able to create a database of every game involving an AP-ranked team in Division I history (nearly 40,000 games dating to the first poll release in 1949).”

That wealth of information has allowed ESPN to lend perspective to contemporary sports stories, like West Virginia’s chance to beat No. 1 Kansas and No. 2 Oklahoma in consecutive games earlier this season. His research allows him to compile a variety of story angles that are pitched to ESPN’s various platforms and appear on both game broadcast and multiple studio shows.

“These archives allowed us to create a one-of-a-kind resource that’s really unrivaled in the industry,” said Farber. “We’ve gotten massive return on the database so far as its information has littered our college basketball coverage all season long.”

Another recent example involves ESPN’s coverage of the Baylor vs. Kansas game last month. According to Farber, Baylor claimed to be 0-15 all-time against the No. 1 and No. 2 teams when ESPN had it as 0-14 in such games.

Newspaper from Jan. 18, 1949, indicating the first AP Poll. Library of Congress.

“After going through the school’s media guide and identifying the relevant games, we cross-referenced that list with our resource and found the discrepancy,” he explained. “Baylor claimed that it played No. 2 Oklahoma A&M on December 29, 1948. Using the newspaper archives, I was able to prove that the AP Poll didn’t even exist for another 2-3 weeks.”

Farber admits to being fascinated with the “snapshot of history” the newspapers have provided. From the style of writing to the older photographs to the general newspaper construction, he’s really immersed himself into how reporters and fans viewed and wrote about sports during an earlier era.

“The window into the past that the Library affords is a unique resource that must be preserved,” he concluded. “The written word is our most direct connection to past generations and provides invaluable information that would otherwise pass as those who experienced it do.

“The Library is a fantastic resource that will hopefully grow and flourish so that others can discover the treasures that it holds.”

March 8, 2016

“Downton Abbey” Lives On at the Library of Congress

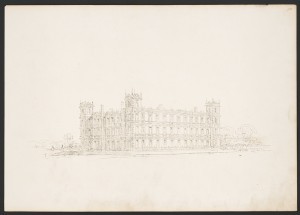

Highclere Castle, 13-bay perspective study in an Elizabethan style with larger corner towers and no central entrance. Prints and Photographs Division.

If you’re a fan of “Downton Abbey,” Sunday night was likely a bittersweet television moment – glad for the happy ending but sad to see the popular show go. As one Library colleague put it, we will all be experiencing “Downton” withdrawals.

The Library of Congress may be able to help with that, however. Recently acquired and added to the institution’s collections are a series of architectural drawings of Downton Abbey – or more accurately, Highclere Castle. These drawings join the Library’s unmatched architecture, design, and engineering collections, including the Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record (HABS/HAER) and the papers of many of the most distinguished figures in the area like Pierre Charles L’Enfant, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, James Renwick, Charles and Ray Eames, Eero Saarinen and many more.

Located in Hampshire, Highclere Castle has been home to the Carnarvon family since 1679. (The Crawley’s moved in six seasons ago.) You can read more about the estate’s real-life inhabitants in an article from the January/February 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Highclere Castle, 9-bay perspective study in the Italianate style with small corner towers and a large separate tower. Prints and Photographs Division.

The home, which sits atop the 1,000-acre property, was transformed to its current splendor in the mid-19th century. In 1838, the third Earl of Carnarvon hired Sir Charles Barry, the architect who designed the neo-Gothic Houses of Parliament in London, to head the renovation project.

According to architecture.com, “Barry’s qualities seem to lie in his versatility. He could deliver whatever the client required, as long as it included ornamentation. … Judging by the high level of decoration on his buildings, Barry seems to have disliked blank spaces.”

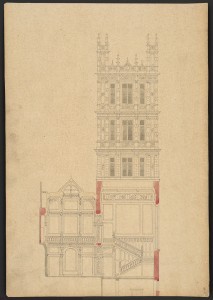

Elevation of Barry’s new central tower in an Elizabethan style above a section of the principal staircase and entrance hall. Prints and Photographs Division.

The mansion is designed in the Elizabethan style, but that wasn’t the original iteration of Barry’s plan. The architect’s early view was based on the Italianate style with small corner towers, pedimented windows and a large separate tower. But, what was old was new again, and, following a movement back to a distinctly British style, Barry transformed the large estate to Elizabethan gothic splendor. A focal point of the home is its central tower, and it is evident Barry was influenced by his design work of the Palace of Westminster.

“It’s the only country home that echoes the Palace of Westminster,” said C. Fort Peatross, director of the Library’s Center For Architecture, Design And Engineering. “Barry was rejecting Classicism and picking up the style of a glorious, previous period.”

“My ancestor asked for a really nice house to be built in bath stone,” explained the present earl of Carnarvon to Architectural Digest in 2012. “Barry said he couldn’t guarantee that it would last one hundred years, since the stone crumbles, but it is 133 years old now. The foundations are 16 feet deep, and so the castle will probably stand up for at least another 500 years.”

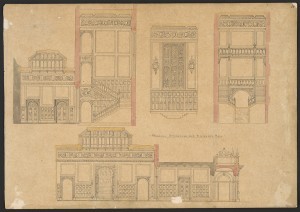

Elevations and sections of Barry’s new principal staircase and entrance hall. Prints and Photographs Division.

Barry supervised the project until his death in 1860. Thus, much of the interior work of the house is not his own. Thomas Allom, who had worked with Barry, completed the project. That’s not to say Barry’s influence isn’t around: he designed elements of the principal staircase and entrance hall.

“[Highclere Castle] is like a jewel box,” said Peatross. “It’s changing every moment of the day in the light.”

And, just as Downton Abbey exists in real life, the storyline isn’t far fetched either. You can read more about that in the Library of Congress blog post. More information about the Library’s architecture and design collections can be found at its Center for Architecture, Design and Engineering.

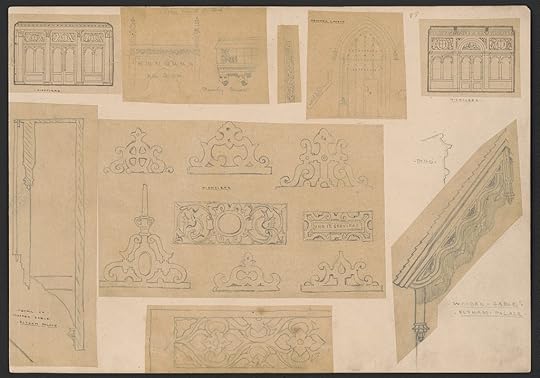

Three sketches highlight designs for Highclere: top left, three-bay interior wall elevation with coupled arched openings and a central doorway framed by four pilasters; top right, alternative scheme, here with an arched central doorway; middle, eight elevation details for parapets and decorative panels including one with the Carnarvon family motto: “Ung je serverai,” old French for “One will I serve.” Prints and Photographs Division.

Three sketches highlight designs for Highclere: top left, three-bay interior wall elevation with coupled arched openings and a central doorway framed by four pilasters; top right, alternative scheme, here with an arched central doorway; middle, eight elevation details for parapets and decorative panels including one with the Carnarvon family motto: “Ung je serverai,” old French for “One will I serve.” Prints and Photographs Division.

March 7, 2016

Library in the News: February 2016 Edition

In February, the Library added a host of resources to its offerings, both onsite and online.

Early February, the Library debuted a new exhibition on “Jazz Singers,” which offers perspectives on the art of vocal jazz, featuring singers and song stylists from the 1920s to the present.

The ArtsBeat blog of the New York Times called the exhibition a “trove of rarities.”

Will Friedwald of the Wall Street Journal wrote, “Jazz is about singing with soul, rhythm and personality, and if you want a visual and inspirational definition of what the music is all about, look no further.”

Deborah Block of Voice of America wrote, “Past and present, they are keeping jazz alive for generations to come.”

The exhibition is also online.

With much anticipation, the Library’s Rosa Parks Collection was added to the Library’s online offerings in February. A selection of photographs, letters, manuscripts and other ephemera reveal many details of Parks’ life and personality.

“I think it’s a wonderful idea that people who cannot travel and do not have the opportunity to travel will have an opportunity to see the brilliance of the mother of the modern civil rights movement,” said Elaine Steele, who, along with Parks, co-founded the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development in Detroit. She spoke with the Detroit News regarding the Library’s collection.

The online presentation was also featured in the New York Times, The Washington Post, the Associated Press and Mashable, among many others.

In collaboration with the WGBH Educational Foundation, the Library launched the American Archive of Public Broadcasting, which recently acquired New Hampshire Public Radio’s digital collection of interviews and speeches by presidential candidates from 1995-2007.

The announcement was also made in Fine Books & Collections Magazine and Radio World.

The Library has also been featured in The Washington Post’s series of “Presidential” podcasts, highlighting our curatorial experts.

And, speaking of presidents, Slate’s “The Vault” blog took a look at a different aspect of George Washington’s career – that of surveyor. The Library holds several maps from his lifelong involvement in surveying and cartography, all of which are available online at the Library.

In addition to these new offerings, the Library recently added to its collections 96 original courtroom drawings by Aggie Kenny, Bill Robles and Elizabeth Williams that show high-profile trials from the past four decades.

“The hand-drawn moments take us inside some of the most famous trials of recent decades, to scenes only made visible by the ongoing work of courtroom artists,” wrote Allison Meier for Hyperallergic.com.

The New York Times and Associated Press also featured stories on the courtroom drawings acquisition.

March 4, 2016

Pic of the Week: Read Across America

“You’re never too old, too wacky, too wild, to pick up a book and read with a child.” ~ Dr. Seuss

Kahin Mohammad of the Young Readers Center displays a special braille and written edition of “Green Eggs Ham” to students during Read Across America day. Photo by Shawn Miller.

On Wednesday, children gathered at the Library’s Young Readers Center for “Read Across America” day, which also coincides with the birthday of Dr. Seuss.

The National Education Association’s signature program is now in its 19th year. The event at the Library was one of many across the nation to celebrate the joy of reading and motivate children and teens to read.

March 2, 2016

New Online: Rosa Parks, Page Upgrades, Search Functionality

(The following is a guest post by William Kellum, manager in the Library’s Web Services Division.)

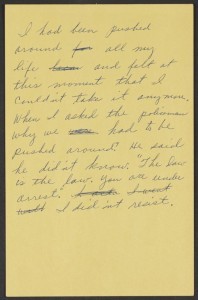

This item from the Parks’ collection documents her reflections on her bus arrest, circa 1956-1958.

In February, the Library of Congress added the Rosa Parks Papers to its digitized collections. The collection contains approximately 7,500 manuscripts and 2,500 photographs and is on loan to the Library for 10 years from the Howard G. Buffett Foundation. Included in the collection are personal correspondence, family photographs, letters from presidents, fragmentary drafts of some of her writings from the time of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, her Presidential Medal of Freedom, her Congressional Gold Medal and more.

The online presentation includes a video that contains highlights from the collection and a look behind the scenes at how the Library’s team of experts in cataloging, preservation, digitization, exhibitions and teacher training are making the Parks’ legacy available to the world.

To support teachers and students as they explore this one-of-a-kind collection, the Library is offering a Primary Source Gallery with classroom-ready highlights from the Rosa Parks Papers and teaching ideas for educators.

Along with digitized materials like the Rosa Parks Collection, the Library continues to add new born-digital materials to its website. The Library’s Web Archives have recently been updated with content collected during the 2012 and 2014 United States Elections.

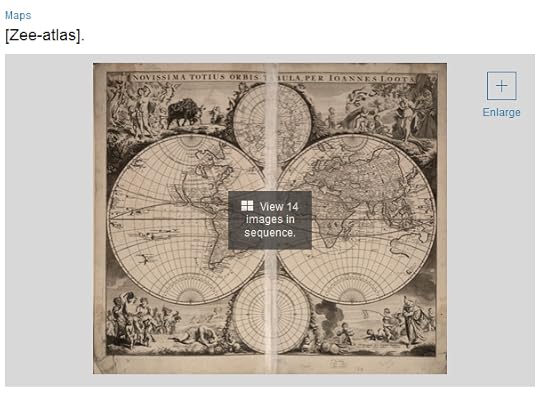

February also brings some changes to our overall presentation – we’ve upgraded all of our item detail pages (the page where you view bibliographic data alongside a digital resource, like an image or video). All pages now feature an improved, simplified layout for all screen sizes, larger thumbnails, simplified download links and easier access to “rights and access” information. We’ve also added an overlay so that you can tell when an item has multiple pages, such as in a folder of manuscripts, or an atlas, like this circa 1700 volume with 14 images to view:

Also new on item pages is our beta Cite This Item widget. Users can click to see the bibliographic data for the item formatted in Chicago, APA and MLA styles.

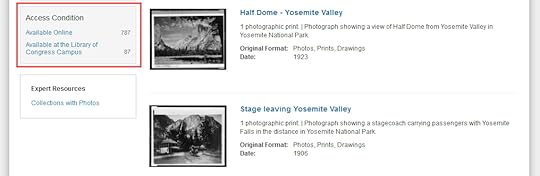

Since searching our website is the way most users interact with our content, we’ve added a new search facet (aka filter) to help users find digital content based on whether it’s fully available online or not. Look down the left hand side of a search results page (like this search for photos of “Yoesmite”), and you’ll see a box labelled “Access Condition” – you can use that filter to limit your results to items fully available, or items that only display a thumbnail and that you need to come to our reading rooms to see in their entirety.

A few other new things worth noting are now online: “Jazz Singers,” a new exhibit on the art of vocal jazz from the 1920s to the present; The Mexican Revolution and the United States in the Collections of the Library of Congress, an upgraded presentation describing the “complex and turbulent relationship between Mexico and the United States during the Mexican Revolution, approximately 1910-1920” drawn from primary source items in the Library’s collections; and Women’s History Month 2016, an update of our collaborative portal with links to featured content from the Library and our partners at the Smithsonian, National Endowment for the Humanities, National Park Service, and the National Archives.

February 29, 2016

The Ottoman Armenian Merchant from Arapkir

(The following is a guest post by Levon Avdoyan, Armenian and Georgian area specialist in the African and Middle Eastern Division.)

The opening page of Poghos Garabedian’s memoirs and genealogy. African and Middle Eastern Division.

Poghos Garabedian started his personal memoirs with a flourish. Within the next 41 pages, this merchant in the Ottoman Empire – originally from Arapkir in the region of Malatya, Turkey – would detail his extensive mercantile travels to Constantinople, the Crimea, Arapkir and Eastern Europe. He would also, in good patriarchal fashion, advise his children on the way to be good merchants, Christians and Armenians. Garabedian also details his days as the purveyor of the pantry in the Khedive’s court in Cairo. Last, he describes the donations he has made to Armenian institutions in Constantinople, Arapkir and many of the other places he has journeyed.

The Near East Section of the African and Middle Eastern Division recently acquired this manuscript, which was created in Cairo around 1877 and was written in what the Armenians call hayatar Turkeren (Turkish in Armenian letters) – now known as Armeno-Turkish. Curiously, Garabedian appends a family genealogy on pages 41-45, written in Armenian with Arabic numerals. Why this dichotomy? Could it have been that Garabedian intended the memoirs for a broad audience of both Armenians and others, while he realized the genealogy would be of interest only to Armenians?

Armeno-Turkish is a phenomenon in the Ottoman Empire that started in the early 18th century and lasted well into the mid-20th century. These works – hand-written manuscripts, published books, newspapers, journals, serials and pamphlets – were literally written in the Turkish language but with the use of the Armenian rather than the prevalent Arabic script. The simplistic explanation has always been that Armenians who knew Turkish used Armeno-Turkish but not when it was written in the Arabic script. Recently, scholarship has debunked this explanation and has revealed its use as a separate and creative phenomenon. Works written and published in Armeno-Turkish were known and used not only to Armenians but also to Ottoman intellectuals and functionaries.

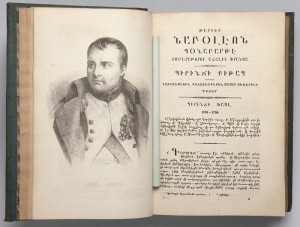

Engraving of the Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte from Hovsep Vartanian’s two-volume history. African and Middle Eastern Division.

The Library’s growing collection of Armeno-Turkish works includes a two-volume history of Napoleon Bonaparte by Hovsep Vartanian, which gives us a potential answer. During the course of a lecture he delivered in Yerevan, Armenia, in 2014, Murat Cankara of the Social Sciences University of Ankara theorized that Vartanian was also the author of the anonymous Armeno-Turkish “Akabi Hikayesi,” the first novel published in the Ottoman Empire. (Alas, the Library only has a 1991 edition of this seminal work). What was especially intriguing, however, was Cankara’s translation of a passage from the history of Napoleon in which Vartanian discussed his reasons for using Armeno-Turkish.

“Before we conclude, a reservation comes to mind: there will also be people who ask ‘in any event, wouldn’t our mother tongue, the Armenian language be preferable for writing such a history?’ Our humble answer to them [is this]: Turkish or Armenian, whatever the language is, in order to be able to benefit from reading such a history one should have studied thoroughly either of these languages. As a matter of fact, the number of those who are familiar with classical Armenian is quite limited and vernacular Armenian’s rules have not been established as yet, so writing a book in this language necessitates using words from Classical Armenian in every line. And in order to understand a book written in the vernacular, one needs to take on the burden of learning classical Armenian. It seems also that some Ottoman Armenians from that same period advocated the use of the Armenian script over the Arabic for much the same reasons.”

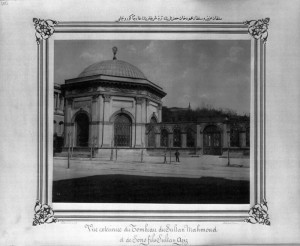

The Mausoleum of Sultan Mahmud II and his son Sultan Abdülaziz. Prints and Photographs Division.

Whatever the reasons for its use, works in Armeno-Turkish span several disciplines, although the preponderance of them are either translated or original religious works and of those, most are of the New Testament. The Library of Congress’s expanding collection includes inter alia, novels, histories, philosophical and geographic works, almanacs, veterinary studies, dictionaries and newspapers. Researchers may find a comprehensive list in our online catalog by entering the key word “armeno-turkish.”

This discreet collection of materials, which is housed in the Near East Section complements other collections in the Library of Congress that testify to the important role of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. One such collection in the custody of the Prints and Photographs Division has also been fully digitized and made available to the public. The album presented to the United States by Sultan Abdul Hamid II (1842-1918) consists of photographs of the Ottoman Empire taken by his court photographers, who were three Armenian brothers known collectively as Abdullah frère.

February 26, 2016

Pic of the Week: My Life in Medicine

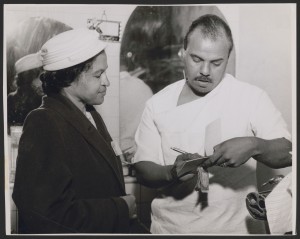

Louis W. Sullivan discusses his book “Breaking Ground: My Life in Medicine.” Feb. 24, 2016. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Louis W. Sullivan, former secretary of Health and Human Services, discussed his new book, ”Breaking Ground: My Life in Medicine” (University of Georgia Press, 2014), on Wednesday during an author talk presented by the Center for the Book in the Library of Congress. A video of the presentation will be available in the coming weeks.

Sullivan spent his childhood in Jim Crow southern Georgia. At the age of 5, he told his mother that he wanted to be a doctor. Schools in Blakely, Georgia, were segregated at the time, so his parents sent him to Savannah and later to Atlanta for his education. After graduating from Morehouse College, he attended medical school at Boston University, where he was the sole African American in his class. According to Sullivan, he was also the first graduate of Morehouse to attend. It was also the year Brown v. Board of Education came out.

“I wondered how I would be received,” Sullivan said. “Would it be with hostility, indifference, or would I be welcomed?”

He was well-received, even serving as class president for two years.

Several years later, the dean at Morehouse asked Sullivan to found a medical school there.

“The rationale for creating a medical school at Morehouse was to increase the number of black physicians,” he explained.

During that time, Sullivan developed a relationship with George H.W. Bush, who appointed him Health and Human Services secretary.

“I was impressed by the dedication of the employees,” he said of his time at the agency.

Desiree Arnaiz of the Library’s Center for the Book contributed to this report.

February 25, 2016

Rosa Parks Collection Now Online

The Rosa Parks Collection at the Library of Congress has been digitized and is now online.

Rosa Parks collecting NAACP membership dues of $2.00, likely during her trip to Los Angeles, California, in 1956. Photograph by McLain’s Photo Service. Prints and Photographs Division.

The collection, which contains approximately 7,500 manuscripts and 2,500 photographs, is on loan to the Library for 10 years from the Howard G. Buffett Foundation. The Library received the materials in late 2014, formally opened them to researchers in the Library’s reading rooms in February 2015 and now has digitized them for optimal access by the public.

Parks became an iconic figure in history on Dec. 1, 1955, when she refused to give up her seat to a white passenger on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Her arrest sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a seminal event in the Civil Rights Movement. Parks died at age 92 in 2005.

The collection reveals many details of Parks’ life and personality, from her experiences as a young girl in the segregated South to her difficulties in finding work after the Montgomery Bus Boycott; from her love for her husband to her activism on civil rights issues.

Included in the collection are personal correspondence, family photographs, letters from presidents, fragmentary drafts of some of her writings from the time of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, her Presidential Medal of Freedom and Congressional Gold Medal, additional honors and awards, presentation albums, drawings sent to her by schoolchildren and hundreds of greeting cards from individuals thanking her for her impact on civil rights. The vast majority of these items may be viewed online. Other material is available to researchers through the Manuscript and Prints and Photographs reading rooms.

This video contains highlights from the collection and a look behind the scenes at how the Library’s team of experts in cataloging, preservation, digitization, exhibition and teacher training are making the legacy of Rosa Parks available to the world.

{mediaObjectId:'2AE3F5810A6B0062E0538C93F1160062',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

The Rosa Parks Collection joins additional important civil rights materials at the Library of Congress, including the papers of Thurgood Marshall, A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, Roy Wilkins and the records of both the NAACP and the National Urban League. The collection becomes part of the larger story of our nation, available alongside the presidential papers of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln, and the papers of many others who fought for equality, including Susan B. Anthony, Patsy Mink and Frank Kameny.

To support teachers and students as they explore this one-of-a-kind collection, the Library is offering a Primary Source Gallery with classroom-ready highlights from the Rosa Parks papers and teaching ideas for educators.

February 24, 2016

Saving America’s Radio Heritage

(The following is a guest post by Gene DeAnna, head of the recorded sound section in the Library’s Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division.)

The Library of Congress Packard Campus National Audio-Visual Conservation Center. Photo by Shawn Miller.

I’m often asked what sound recordings are most at risk of being lost before we are able to preserve them. The fact is, the two-headed monster of physical degradation and technological obsolescence can make virtually any recording a challenge to preserve. But there are two analog formats, lacquer discs (also called “acetates” or “instantaneous discs”) and magnetic tape (in a multitude of sizes and formats) that standout as particularly vulnerable and challenging to archivists. This is especially true given their long and widespread use for both commercial and non-commercial audio recording. What is more, with very few exceptions our entire recorded radio legacy, spanning from the early 1930s into the 1990s, was recorded on one of these fragile mediums. Consider also that from 1940-1945 the World War II aluminum embargo resulted in the adoption by radio stations of glass-based lacquer discs, perhaps the most fragile audio medium of all.

This week, the Radio Preservation Task Force of the Library of Congress National Recording Preservation Board convenes a two day conference, “Saving America’s Radio Heritage: Radio Preservation, Access and Education.” The conference will feature scholars, media professionals and audiovisual archivists discussing the cultural and historical significance of radio, the challenges to preserving and providing increased public access and awareness, and the strategies we’ll need to meet all these challenges.

The United States Congress mandated the preservation of broadcast recordings 40 years ago in the 1976 revision of the copyright law, which included the instruction to the Library of Congress to create the American Television and Radio Archives (ATRA) to “preserve a permanent record of the television and radio programs, which are the heritage of the people of the United States.” Since then, under the aegis of ATRA, the Library has acquired, cataloged and preserved tens of thousands of radio broadcasts. Major collections at the Library include the NBC Radio Collection, WOR (Mutual) Collection, Office of War Information (OWI), Voice of America (VOA), the vast Armed Forces Radio and Television Collection (AFRTS) and the National Public Radio Collection.

Audio engineer Brian Hoffa loads cassettes for parallel digitization. Photo by Gene DeAnna.

At the Packard Campus for Audiovisual Conservation, the digital preservation of radio recordings is an ongoing priority of the Recorded Sound Section. To maximize productivity we employ two modes of digital preservation that are determined by the format, playback characteristics and the audio content of the recording. A high throughput parallel transfer mode is used for tapes with predictable and low fidelity content (e.g, spoken word), like professionally recorded cassettes and radio broadcasts on reels.

Just to gauge what a typical day’s radio preservation work might cover, I took a walk through the Audio Preservation Unit, stopping in each sound studio to see what radio recordings were being digitized. Even my high expectations were exceeded:

In the A2 high-throughput studio where up to eight cassettes can be transferred in parallel, the syndicated interview and call-in radio show “Sports Byline” was in process. I saw programs from 2003 featuring basketball legend Kareem Abdul Jabbar and the late Baseball Hall of Famer, Kirby Puckett being preserved.

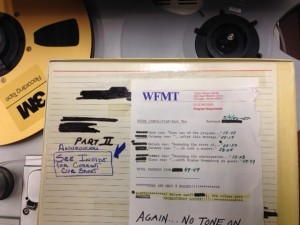

A reel from the Studs Terkel Collection is ready for digitization. Photo by Gene DeAnna.

Next door in a parallel transfer studio for reel-to-reel tape digitization, several reels of the Studs Terkel radio show were running, including a 1970 program on the life of the great French cabaret singer Edith Piaf. Under a cooperative agreement with the Chicago History Museum, the Library of Congress is preserving the entire Studs Terkel Collection, covering over 20 years of his WFMT Chicago radio show. WFMT has launched a website, the Studs Terkel Radio Archive, where the public can listen to many of the programs preserved at the Packard Campus.

In an A1 “expert transfer” studio for recordings from the American Folklife Center, I was surprised and excited to find a lacquer disc from the Alan Lomax Collection of a BBC radio program of Argentine folk music from the late 1930s on the turntable. What a great representation of the breadth and richness of recorded radio!

Audio Engineer Robert Cristarella preserves a lacquer disc of a BBC broadcast from the Alan Lomax Collection. Photo by Gene DeAnna.

In the next studio, a master tape of the classical music program “Adventures in Sound” was rolling and the dazzling sound of Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Scheherazade” poured from the room as I opened the soundproof doors. “Adventures in Sound” featured high quality recordings on FM stereo broadcasts for classical music connoisseurs in the 1970s. It is easy to forget how good radio could sound even 40 years ago.

Finally, in a parallel transfer studio with seven tape decks running concurrently, 10-inch reel tapes from the vast NBC Radio Collection were being digitized. Here I found a 1960 Oscar Hammerstein Memorial program running next to a 1946 broadcast of a speech by President Harry Truman. Three reels of miscellaneous news and information programs from the late 1940s were followed by reels holding “Portia Faces Life” and “Backstage Wife” episodes, both classic radio “soaps” from 1941. So here were exemplars of music history, political history and popular culture being preserved for posterity in a single pass of parallel digitization.

A 1945 NBC Radio broadcast on a 16-inch glass-based lacquer disc. Photo by Gene DeAnna.

These tapes and tens of thousands others were recorded from original NBC lacquer discs by Library of Congress engineers, in what could be the longest ongoing audio preservation project ever. The original NBC Collection arrived at the Library in 1978 in the form of 170,000 16-inch lacquer discs dating from 1933-1960s, including 40,000 wartime glass-based records. In all, about 42,000 hours of airtime is captured in these thin layers of cellulose lacquer, and for decades our engineers transferred them, one 15-minute disc side at-a-time, to tape.

In conjunction with a decades-long cataloging effort, the project brought this remarkable broadcast collection to the public’s ear for the first time since the programs were broadcast into the ether, and it made our current digitization effort possible as well. In what is our 38th year of preserving NBC radio, the tapes are themselves being reformatted to archival standard, high-resolution broadcast wave files, which are archived in the Packard Campus digital repository. The original lacquer discs, considered the master source recordings, are shelved under ideal storage conditions in the Packard Campus’ underground vaults.

Radio broadcasts – and the NBC Collection in particular – continue to be our most publicly requested audio materials. Files from the digital archive are played “on demand” by listeners in the Recorded Sound Research Center in the Library’s Madison Building in Washington, D.C.

Forty years ago Congress declared broadcasts to be an important part of our national legacy and mandated they be preserved for future generations. The Library of Congress continues to play a significant role in that effort, and this week’s conference provides an important opportunity to expand awareness of our recorded radio legacy and develop preservation and access strategies for the 21st century.

February 23, 2016

Obamabilia at the Library

(The following is a guest post by Eve M. Ferguson, reference librarian for East Africa in the African and Middle Eastern Division.)

A sampling of African newspapers with Obama’s election headlines. African and Middle Eastern Division.

As President Barack H. Obama gave his final State of the Union Address last month and this month is , there is no better time to recount the birth of a unique collection at the Library of Congress: the Obama Memorabilia from Africa collection housed in the African and Middle Eastern Division (AMED).

Son of Barack Obama Sr., a native of western Kenya, President Obama has long been well-respected by Africans for his unique journey into becoming the first African American president of the United States. The Library of Congress’ Obama Memorabilia from Africa collection was thus born out of the enthusiastic response Africans had to Obama’s election in 2008, resulting in a plethora of ephemera first acquired by the Library’s Nairobi Office – one of the six Library of Congress overseas offices – and then joined by the collection developed by AMED.

The Obama Memorabilia collection did not come together easily. In 2008, on the very day when the Nairobi office staff set off to acquire memorabilia items, the Nairobi City Council initiated a crackdown on unregulated street vendors, which was the main source for such Obama memorabilia. Fortunately, patience and persistence paid off. A few days later, those street vendors reappeared and the Nairobi Office staff was able to quickly complete their acquisition.

At the same time, the Library’s AMED staff in Washington D.C. were planning to acquire any publications available in Africa on the 2008 election. This would not have been achieved without tremendous support from the State Department Information Resources Officers across the African continent. The result of this seamless collaboration was a comprehensive collection of local newspapers and magazines announcing the results of the U.S. presidential election.

Music CDs inspired by Obama’s historic election. African and Middle Eastern Division.

Since then, the Obama Memorabilia collection has continued to grow. In addition to the Library’s regular acquisitions channels, a series of displays at the Library between 2009 and 2015 attracted donations from the general public to the Library, which further augment this collection. Today, the Obama Memorabilia collection includes newspapers, electoral buttons, photographs, magazines, textiles and music CDs from various African countries, as well as other parts of the world such as France, Lebanon, United Arab Emirates and the United Kingdom. This collection documents not only the historic event in 2008 but also President Obama’s reelection in 2012 and his two visits to Africa in 2013 and 2015.

As President Barack Obama concludes his presidency, he leaves a legacy in ephemera at the Library as a historic record of important research value that documents the enthusiastic responses of African people to his presidency.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers