Library of Congress's Blog, page 130

June 2, 2016

New Online: Education, Folklife, Wartime Collections

(The following is a guest post by William Kellum, manager in the Library’s Web Services Division.)

Educational Outreach

[image error]

The Library’s Student Discovery Sets put primary sources in students’ hands and include full teacher resources for each set.

This month, we’re very happy to have a new release in the excellent series of Student Discovery Sets produced by the Library’s Education Outreach team. Designed for classroom use on Apple’s iPad platform, Student Discovery sets “bring together historical artifacts and one-of-a-kind documents on a wide range of topics, from history to science to literature. Interactive tools let students zoom in, draw to highlight details, and conduct open-ended primary source analysis. Full teaching resources are available for each set.” The new release includes sets on The New Deal, Scientific Data: Observing, Recording, and Communicating Information and Weather Forecasting. These materials are also available via the web as part of the Library’s Primary Source Sets.

You can read more about them on the Teaching with the Library of Congress blog.

American Folklife Center

The American Folklife Center is marking its 40th anniversary in 2016, celebrating the center’s role in the preservation and promotion of traditional culture with a series of events, programs, and other activities throughout the year. New to the Library’s website is the Chicago Ethnic Arts Project Collection, the first online release of materials from approximately 25 ethnographic field projects and cultural surveys in various parts of the United States between 1977 and 1997. The Chicago collection includes photos, audio and the notes and reports of the AFC fieldworkers. This blog post on Folklife Today has more details and samples from the collection. Also new from AFC are four albums of music originally published on vinyl, now online for streaming and download: Folk music of the United States: Indian songs of today; Cowboy songs, ballads and cattle calls from Texas; American fiddle tunes; and Negro blues and hollers. Scans of the original album covers and liner notes are included on the pages (under the PDF link).

Wartime Collections

[image error]

American Fiddle Tunes is one of 4 albums now available for streaming and download, released to celebrate American Folklife Center’s 40th Anniversary.

Expanding our extensive Civil War-related collections, the papers of reformer, poet, editor and clergyman William Oland Bourne span the years 1841-1885, with the bulk of the material concentrated in the period 1856-1867. As editor of the periodical The Soldier’s Friend, Bourne sponsored a contest in 1865-1866 in which Union soldiers and sailors who lost their right arms by disability or amputation during the Civil War were invited to submit samples of their penmanship using their left hands. The online presentation contains correspondence and broadsides concerning the contests, many of the penmanship entries submitted and photographs of some contest participants.

World War I: American Artists View the Great War is an online exhibition of posters, cartoons, fine art prints and drawings chronicling World War I from its onset through its aftermath. You can visit the exhibition in person through May 6, 2017, at the Library’s Jefferson Building Graphic Arts Gallery.

Digital Collection Upgrades

Finally, we’re continuing our migration of old presentations to newer technologies. The latest to receive an upgrade is Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers Project, 1936-1938, which contains more than 2,300 first-person accounts of slavery and 500 black-and-white photographs of former slaves. These narratives were collected in the 1930s as part of the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP) of the Works Progress Administration, later renamed Work Projects Administration (WPA).

May 30, 2016

Rare Survivor of Pacific War

(The following story was written by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library of Congress staff newsletter, The Gazette.)

[image error]

Brothers John (from left), George and Glen Pearcy donated their uncle’s diary to VHP. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Before he boarded the ship carrying prisoners of war across the ocean to a forced-labor camp, George Washington Pearcy divided his diary and gave the pieces to two comrades staying behind.

If he didn’t survive the journey, Pearcy hoped, his story somehow would. Pearcy, a POW held by the Japanese during World War II, never made it home to his family. His diary eventually did and, more than 70 years later, found its way to the Veterans History Project (VHP) at the Library of Congress.

Three of Pearcy’s nephews – George, Glen and John Pearcy – donated the diary, along with photos and family letters, to VHP in December.

The diary is a most-rare item: Such journals were common among POWs in German stalags but much less so at the brutal Japanese camps, where they were kept at risk of death.

“He’s representative of a much larger group that did not leave something behind for us to preserve,” VHP archivist Rachel Telford said. “So many prisoners didn’t keep diaries that they could get home to their families. We’re preserving his place in history, but he’s also a stand-in for so many other men who didn’t make it home.”

War in the Pacific

In June 1941, Pearcy graduated from Washington University law school, joined the Army and was assigned to the 66th Coastal Artillery on Corregidor, an island bastion protecting Manila Bay in the Philippines.

Following their attack on Pearl Harbor that December, the Japanese invaded the Philippines. American forces surrendered at Bataan in April 1942 and at Corregidor in May.

Second Lt. Pearcy was taken prisoner and held in a succession of Japanese camps – mostly at Cabanatuan, the largest in the Philippines. Some 9,000 Americans eventually were held at Cabanatuan. Thousands would end up buried just outside the camp’s fence.

While there, Pearcy documented his experiences on whatever scraps he could find – old maps, hospital forms, labels peeled from food cans. He recalled the “mental daze of the men” after Pearl Harbor, the fighting on nearby Bataan, Corregidor’s fall. He made lists: things he remembered on Bataan, diseases he’d suffered and treatments he’d received, a glossary (“toad-stabber=bayonet”), things to do when he returned home (make wine, build up a stock of food, collect veterans’ stories). He recounted everyday life in camp – the attempted escapes, the beating of prisoners, the thieves’ market.

“Two aspects of it were profound to me: the cruelty imposed upon the prisoners and the need to survive, the turning of American prisoners upon each other for food and medicine to survive,” nephew George Pearcy said. “They’re all on death’s doorstep and if you turn your back on your food, it was gone. If you turn your back on your medicine, it was gone.

“They had to protect themselves amongst each other, to a certain extent, as well as against the Japanese.”

And Pearcy recorded the terrible things he saw. He noted that a Japanese sentry had been decapitated, evidently by a Filipino. A few days later, the Japanese paraded into camp carrying battle flags and a Filipino’s head on a pole – a warning against future attacks on their soldiers.

“I have seen pictures of [Japanese] beheadings in China but never expected to see such a barbaric display – especially carrying a human head at the head of a company of troops,” Pearcy wrote.

‘Hell Ship’ Voyage

[image error]

Items from the collection of the late Lt. George W. Pearcy are donated to the Veterans History Project, December 11, 2015. Photo by Shawn Miller.

In 1944, with Gen. Douglas MacArthur moving to retake the Philippines, the Japanese began to evacuate some POWs aboard “hell ships” – freighters known for their terrible conditions.

On Oct. 20, Pearcy and nearly 1,800 other Allied prisoners sailed from Manila Bay aboard the Arisan Maru, packed into cargo holds not nearly big enough to hold them.

“From the outset, the journey was a horror story,” Manny Lawton wrote in “Some Survived: An Eyewitness Account of the Bataan Death March and the Men Who Lived Through It.” “Men were so tightly crowded together that there was scarcely room to lie down. With the hatch covers closed there was no way to get fresh air, and the humid, sweltering 120-degree atmosphere soon became fouled with the stench of unwashed bodies and human waste.

“In their frightening, helpless condition, many men panicked. Some went mad.”

The ship was headed to Japan or one of its territories, where POWs worked as forced laborers. They never made it. On Oct. 24, an American submarine torpedoed the unmarked Arisan Maru, sinking her. Only nine prisoners survived – Pearcy wasn’t one of them.

On the Homefront

Stateside, Pearcy’s family wasn’t sure what had happened to him. His mother wrote him letters, but all came back marked “return to sender.”

The only communications they received during his captivity were a few postcards that mostly allowed Pearcy to choose among preprinted choices: “My health is – excellent; good; fair; poor.”

But Pearcy, fearing the worst before he boarded the Arisan Maru, took a gamble to ensure his story reached home. Figuring his diary had a better chance of survival if it remained behind, Pearcy split his papers between two POWs considered too sick to travel.

The gamble worked. After Pearcy’s death, half the diary got back to his family, in care of a soldier from Utah.

“I don’t know if he presented it or mailed it,” George Pearcy said. “But he got it to them.”

And now it has a permanent place at the Library of Congress.

“We thought it was a story larger than just the Pearcy family,” Pearcy said. “We thought this was the best vehicle to allow the story to be told about what I feel is not just the Pearcy story, but the story of that generation and thousands upon thousands of people that experienced the same doggone thing.”

UPDATE

The story of Pearcy’s diary was also posted on the Folklife Today blog in February in which it garnered quite the interest. One of Robert Auger’s relatives contacted VHP in April with an offer to donate Auger’s POW diary to the Library. You can read more about it here.

May 27, 2016

Pic of the Week: AFC Celebrates 40

Nakotah LaRance gives a hoop dance performance during AFC’s 40th anniversary celebration. Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

The American Folklife Center (AFC) hosted a reception in celebration of its 40th anniversary last Wednesday. Special guests giving remarks were David Mao, acting Librarian of Congress; Kurt Dewhurst, chairman of AFC’s board of trustees; Betsy Peterson, AFC’s current director; and David Isay, founder of StoryCorps.

The reception included a special performance by Nakotah LaRance, the 2015 and 2016 World Hoop Dance Champion. LaRance comes from Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo, New Mexico. He is well known as an actor for roles in Steven Spielberg’s “Into the West” miniseries, HBO’s “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee” and AMC’s “Longmire.” He was also a principal dancer in the Cirque Du Soleil show “Totem” and is currently the master instructor for the Pueblo of Pojoaque Youth Hoop Dancers.

The American Folklife Center was created by Public Law 94-201, The American Folklife Preservation Act, which was signed into law by President Gerald Ford on Jan. 2, 1976. The law placed AFC at the Library of Congress to “preserve and present American Folklife” through programs of research, documentation, archival preservation, reference service, live performance, exhibition, public programs and training. The center includes the American Folklife Center Archive of Folk Culture, which was established in 1928 and has become one of the largest collections of ethnographic material from the U.S. and around the world. The archive includes about 6 million sound recordings, manuscripts, photographs and other items — 5 million of which have been acquired in the last 40 years.

More information on AFC’s 40th anniversary programming and plans can be found here.

May 26, 2016

Coloring Inside the Lines

May 25, 2016

America’s Public Libraries

(The following is the cover story from the May/June 2016 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, written by Yvonne Dooley, reference librarian in the Science, Technology and Business Division and president of the D.C. Library Association. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

Opened in 2012, the Francis A. Gregory branch of the D.C. Public Library was designed by the

architecture team of Adjaye Associates and Wiencek Associates. Maxine Schnitzer, courtesy of D.C. Public Libraries.

More popular than ever, public libraries are changing to meet the needs of the communities they serve.

Despite dire predictions of their demise, America’s public libraries—about 17,000 nationwide—are thriving. Once thought of as a repository and lending place for books, public libraries are now centers for learning, innovation and collaboration. The digital age—with its rapidly changing technology—has required public libraries to evolve or risk becoming obsolete.

More Popular Than Ever

Americans love their libraries. In 2007–2008, during the nation’s economic downturn, public libraries saw an all-time high in usage throughout the country. The Institute of Museum and Library Services reported 1.5 billion in-person library visits in 2008. Patrons came to libraries in droves to use computers, look for jobs and attend classes, in addition to checking out materials. As they did during the Great Depression, people turned to their local public libraries during their greatest time of need. Today, those usage levels have remained unchanged.

A 2013 Pew Research Report on “How Americans Value Public Libraries in Their Communities” found that 90 percent of Americans ages 16 and older said that the closing of their local public library would have an impact on their community, with 63 percent saying it would have a “major” impact.

Jaime Mears, a National Digital Stewardship Resident at Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in Washington, D.C., instructs Alex Santos

on how to scan and digitize family photos in the Memory Lab. Photo by Shawn Miller.

A 2012 “Public Library Funding and Technology Access Study” found that libraries are helping to bridge the digital divide: The study reported that 62 percent of libraries are the only source of free Internet access in their communities; 76 percent offer access to e-books and 39 percent of libraries provide e-readers for check-out by patrons.

Yet, as demand surges, library funding continues to dwindle. The “Public Library Funding and Technology Access Study” also reported that 23 states cut funding in 2012 for public libraries and more than 40 percent of states decreased library support three years in a row.

What’s New at the Public Library?

Today’s public libraries offer something for everyone—at all ages and levels of ability. The District of Columbia Public Library system, for example, is a bustling network of 26 library locations that offer services well beyond those initially conceived by Congress when it established a free public library for the District on June 3, 1896. Not only can District residents check out the latest bestseller or issue of People magazine but they also have free access to the Internet for research or job-hunting, or they can use one of the hands-on “makerspaces” (complete with a 3D printer) available at the central Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library branch. Opened in 1972, the historic MLK Library is scheduled for a major renovation to provide state-of-the-art library services. Several other D.C. public libraries have been renovated in recent years with designs that reflect changes in how the community uses the modern public library.

Public libraries like the Watha T. Daniel/Shaw Library offer patrons access to computer and Internet. Paúl Rivera, courtesy of D.C. Public Libraries

This is not unique to the D.C. area—the evolution is happening in 9,000+ public library systems all over the United States. In October 2014, the Aspen Institute released the report “Rising to the Challenge: Re-envisioning Public Libraries” in an effort to guide critical conversations regarding the future of public libraries. “It is a time of particular opportunity for public libraries with their unique stature as trusted community hubs and repositories of knowledge and information,” the report concluded. “Public libraries must align library services in support of community goals.”

The American Library Association agrees. In October 2015 it launched “Libraries Transform,” a new public awareness campaign to showcase the critical role that libraries play in the digital age.

“The Libraries Transform campaign communicates the message that libraries are neither ‘obsolete’ nor ‘nice to have’—libraries are essential,” said ALA President Sari Feldman. “It is clear that today’s libraries are less about what we have for people and more about what we do for, and with people to create individual opportunity and community progress.”

With support from the American Library Association’s “the American Dream Starts @ your library” initiative, institutions like the Waukegan (Illinois) Public Library are giving new Americans the skills and confidence to improve their lives. Waukegan’s programming includes English Conversation workshops for those for whom English is a second language. Adult ESOL programs are a mainstay of public library programming throughout the nation.

Read to a Dog” programs at public

libraries motivate reluctant young readers. Courtesy of Montgomery (Maryland) County Public Libraries.

When facing budget shortfalls, U.S. mayors report that library budgets are among the first items cut. Donna Howell, the director of Mountain Regional Library System in Georgia sums up the issue: “Our funding has been cut so low that we’re really at the end of our financial tether … but the fact that we’re still relevant enough to our community for them to keep coming back in such large numbers gives me hope for our future.”

“Los Angeles is a gateway city and serving our immigrant communities is an extremely high priority for us,” said John Szabo, city librarian of the Los Angeles Public Library. “In 2012, we launched a partnership with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services—the agency that oversees naturalization—to provide resources that assist new Americans in taking their first steps on the path to citizenship. Our program has become a national model and is evolving into an even more robust immigrant integration effort. This work is beautifully aligned with the values of libraries and librarianship and is strategically important to our present and our future.”

Library programs using Legos support the STEM curriculum. Courtesy of Montgomery County

(Maryland) Public Libraries.

Today’s public libraries are bright, airy, inviting meeting spaces, with comfortable furniture in open floorplans. In addition to makerspaces, some even include coffee shops, toylending collections, passport acceptance centers—the list goes on and on.

Makerspaces allow the creative community to take advantage of new tools to produce products and take them directly to the marketplace on the web. Makerspaces also foster interest in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math). More than 30 libraries in the state of Idaho have implemented STEM programming that encourages the use of new technology and tools. Montgomery County (Maryland) Public Libraries offer “creating with Legos” programs for elementary school children that support the STEM curriculum.

For reluctant young readers, many public libraries offer a “Read to a Dog” program. For reluctant users of technology, the public library is the place to go to learn how to download e-books to mobile devices.But as wonderful as all these new public library programs are, they mean nothing if people do not take advantage of them. Like a best-selling novel that gets shelved in the nonfiction section, if no one finds and uses it, it might as well not be there.

May 20, 2016

Pic of the Week: Music Makers

Monica

On Tuesday, the Library hosted the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) Foundation for its annual “We Write the Songs” concert, featuring the songwriters performing and telling the stories behind their own music.

Featured performances were by Brian McKnight, Monica, Brett James, MoZella, Priscilla Renea, Randy Goodrum, Desmond Child and Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Jennifer Higdon.

Priscilla Renea and Brett James

The Library is home to the ASCAP collection, which includes music manuscripts, printed music, lyrics (both published and unpublished), scrapbooks, correspondence and other personal, business, legal and financial documents, scrapbooks, and film, video and sound recordings.

Brian McKnight

Established in 1914, ASCAP is the first United States Performing Rights Organization (PRO), representing the world’s largest repertory of more than 10 million copyrighted musical works of every style and genre from 525,000 songwriter, composer and music-publisher members.

You can find videos of previous “We Write the Songs” concerts on the Library of Congress YouTube channel.

All photos by Amanda Reynolds

May 19, 2016

Page from the Past: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

(The following is a story featured in the May/June 2016 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here. The story was written by August and Clare Imholtz, who have been collecting “Alice” books for more than 30 years. Clare is also a volunteer in the Library’s Rare Book and Collections Division.)

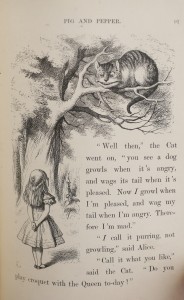

This illustration by John Tenniel depicts Alice and the Cheshire Cat.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”— a book that has never been out of print since its original publication 150 years ago—did not get off to a good start.

The classic tale about a little girl who falls down a rabbit hole into a fantasy world populated by an odd cast of characters was first published in Oxford during the summer of 1865. Displeased with the quality of the printing, illustrator John Tenniel persuaded the author, Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832-1898)—who would become famous under his pen name, “Lewis Carroll”—to recall that edition of 2,000 copies, except for about 50 copies that had already been distributed to friends. The still unbound sheets of the 1865 “Alice” were sold to the American firm of D. Appleton and Co., which published the work in New York in 1866 with a new title page. A copy of the “Appleton Alice” came to the Library in the personal book collection of Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, following his death in 1935.

Even rarer than the Appleton edition of “Alice” is the Library’s copy of the first approved edition of “Alice,” published in November 1866 in London by Macmillan & Company. The Library’s copy, which it purchased in 1924, has two original pencil drawings by Tenniel (sketches of the “Seven and Five of Hearts” and “Alice, the Duchess, and the Flamingo”) tipped in. These drawings most likely were commissioned from Tenniel subsequent to the book’s publication.

“Alice” grew out of a fanciful tale that Carroll told the three daughters of Henry Liddell, Dean of Christ Church, Oxford, during a boat trip in the summer of 1862. Several years later, he presented one of the daughters—Alice—with his handwritten and self-illustrated manuscript copy of the story titled “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground,” which she had urged him to put in writing for her. Purchased by Eldridge Reeves Johnson, inventor of the Victor Talking Machine, the manuscript was exhibited at the Library of Congress from October 1929 to February 1930. After Johnson’s death in 1945, the manuscript was purchased at auction by a group of Americans led by Lessing Rosenwald, A.S.W. Rosenbach and Librarian of Congress Luther Evans. On Nov. 13, 1948, Evans presented the manuscript to the British Museum as a gift to Great Britain from a group of anonymous Americans in gratitude for Britain’s heroic efforts in holding Hitler at bay until the United States entered World War II.

When the Alice books were published, they were copyright protected for 42 years after the first publication or seven years after the author’s death, whichever was longer. Thus, the work itself entered the public domain in 1907, thereby inspiring numerous illustrated editions, comic books and adaptations for film, stage and television over the past century. Most notable are the 1951 Disney film and Tim Burton’s 2010 film. Most recent is an online version with annotations from 12 Carroll scholars offered by The Public Domain Review to mark the 150th anniversary of the timeless tale.

LEWIS CARROLL SCRAPBOOK

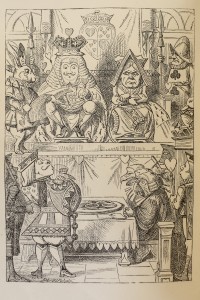

This frontispiece from the earliest editions of “Alice’s Adventures in

Wonderland” is by John Tenniel.

Perhaps the rarest Carroll treasure owned by the Library is a scrapbook he kept from 1855 to 1872. Carroll spent his whole adult life at Christ Church, Oxford—first as an undergraduate and later as a mathematics lecturer. The scrapbook consists of more than 100 items, mostly of clippings from newspapers and periodicals, which offer an interesting window into Carroll’s mind.

They include reviews of his own published works, pages from the humor magazine “Punch,” clippings on Oxford and British politics, theater reviews, poetry, major news events of the day and cartoons that evidently appealed to Carroll’s sense of humor and his fascination with nonsense and the absurd. A review of his “Formulae of Plane Trigonometry” from the Athenaeum of July 27, 1861, shared a page in the scrapbook with a memorial poem on the death of Prince Albert from “Punch.”

Frederic Louis Huidekoper, an American undergraduate at Christ Church, purchased the scrapbook at a sale of Carroll’s effects shortly after his death in 1898. Col. Huidekoper, who distinguished himself in World War I and was awarded the Chevalier de Legion of Honor, became a respected and prolific military and naval historian. In 1934, he donated Carroll’s scrapbook to the Library just six years before his death in a trolley car accident in Washington, D.C.

May 12, 2016

Pic of the Week: American Artists View WWI

“World War I: American Artists View the Great War” is on view through May 6, 2017. Photo by Shawn Miller.

On Saturday, the Library of Congress opened the new exhibition, “World War I: American Artists View the Great War,” highlighting how American artists galvanized public interest in World War I.

Drawn from the Library’s Prints and Photographs Collections, the works on display reflect the focus of wartime art on patriotic and propaganda messages—by government-supported as well as independent and commercial artists.

Many of the artists featured in the exhibition worked for the federal government’s Division of Pictorial Publicity, a unit of the Committee on Public Information. Led by Charles Dana Gibson, a preeminent illustrator, the division focused on promoting recruitment, bond drives, home-front service, troop support and camp libraries. Many images advocated for American involvement in the war and others encouraged hatred of the German enemy. In less than two years, the division’s 300 artists produced more than 1,400 designs, including some 700 posters.

Heeding the call from Gibson to “Draw ‘til it hurts,” hundreds of leading American artists created works about the Great War (1914–1918). Although the United States participated as a direct combatant in World War I from 1917 to 1918, the riveting posters, cartoons, fine art prints and drawings on display chronicle this massive international conflict from its onset through its aftermath.

Among those who heeded the call were James Montgomery Flagg (best known for his portrayal of Uncle Sam), Wladyslaw Benda, George Bellows, Joseph Pennell and William Allen Rogers. In contrast, such artists as Maurice Becker, Kerr Eby and Samuel J. Woolf drew on their personal experiences to depict military scenes on the front lines as well as the traumatic treatment of conscientious objectors. Finally, cartoonists offered both scathing criticism and gentle humor, as shown in Bud Fisher’s comic strip “Mutt and Jeff.”

Photography also provided essential communication during the First World War. The selected images detail the service of soldiers, nurses, journalists and factory workers from the home front to the trenches. American Red Cross photographs by Lewis Hine and others employ artful documentation to capture the challenges of recovery and rebuilding in Europe after the devastation of war.

The exhibition is made possible by the Swann Foundation for Caricature and Cartoon, and is the first in a series of events the Library is planning in connection with the centennial of the United States’ entry into World War I. With the most comprehensive collection of multi-format World War I holdings in the nation, the Library is a unique resource for primary source materials, education plans, public programs and on-site visitor experiences about The Great War, including exhibits, symposia and book talks.

May 10, 2016

Happy 180th Birthday to Col. Nathan W. Daniels

(The following is written by Michelle Krowl, a historian in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division.)

On May 10, 1867 Colonel Nathan W. Daniels celebrated his 31st birthday. He noted in his diary, “Learned to day that I had been recommended and nominated by Chief Justice Chase as Register under the Bankrupt Act for the 4th Dist of Louisiana and my name sent on to the District Judge for confirmation.” After erroneously recording his age as 32, he commented that his new position made “a very acceptable birthday present.” “So now we are off for Louisiana and prosperity I trust,” he wrote.

This would not be the first time Louisiana played an important role in the diaries kept by Nathan W. Daniels, which are now online as part of the Nathan W. Daniels Diary and Scrapbook, 1861-1867.

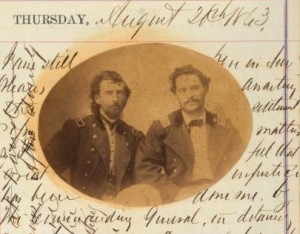

Colonel Nathan W. Daniels (left) and Major Francis E. Dumas (right), officers of the 2nd Regiment of Louisiana Native Guard. From vol. 1 of the Nathan W. Daniels Diary. Manuscript Division.

Born in New York on May 10, 1836, Nathan W. Daniels had moved to Louisiana prior to the Civil War. After the capture of New Orleans by United States forces in 1862, Union general Benjamin F. Butler allowed the enlistment of Native Guard units comprised of “free men of color” and former slaves. Loyal to the Union and holding abolitionist sympathies, Daniels became the colonel of the 2nd Regiment of the Louisiana Native Guard. As was the case with many African-American regiments formed later in the war, most of the officers of the 2nd Regiment were white men like Daniels, but Daniels recommended African-American planter Francis E. Dumas for the rank of major. Perhaps as an indication of his respect for Major Dumas, they were photographed together and Daniels pasted a print of the photograph into his wartime diary.

Daniels acquired the first volume of his three-volume diary when he confiscated it from the New Orleans home of cotton merchant Hamilton McNeil Vance and his wife Lizzie Luckett Vance. They left the partially-used diary behind when they fled New Orleans in 1862, and Daniels found the volume in November 1862 and appropriated it for his own use. His first entries listed “suspicious characters” among captured prisoners, but he soon began using the volume to record the activities of the 2nd Regiment after it was posted to Ship Island, off the coast of Mississippi. The 2nd Regiment saw action at the battle of Pascagoula in Mississippi in April 1863, which Daniels recorded in diary entries from April 9 –12, 1863. Although the unit was ultimately forced to retreat, Daniels wrote a laudatory address to his soldiers. “You have tested the question of your nations valor, and demonstrated to its fullest extent the capacity—the bravery—the endurance and nobility of your race….”

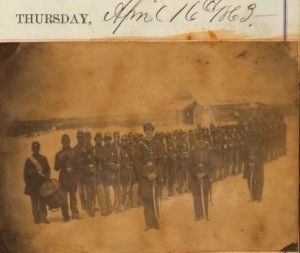

Even more valuable historically than Daniels’s descriptions of the 2nd Regiment’s time on Ship Island are the rare photographs taken on the island, prints of which Daniels pasted into his diary. The photographs include structures built on the island, the terrain, the men in the regiment, an ambulance wagon, a battery constructed by Daniels’s troops, as well as images of Daniels and his fellow officers.

“Picture presented me by the Capt of ‘Company C,’ Capt Chase of my Regiment,

not very good still well for Ship Island.” From vol. 1 of Nathan W. Daniels Diary. Manuscript Division.

After essentially being forced out of the army in August 1863, Daniels moved to Washington, D.C. that fall and many of the observations recorded in his diary document aspects of the nation’s capital during the Civil War. In addition to meeting with President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, Daniels watched workmen installing the Statue of Freedom on the Capitol dome. On Jan. 9, 1864, he mentions the prevalence of smallpox in the city, although he happily notes that in the process of vaccinating his friend Jeanie Foster he “had the pleasure of seeing her beautiful white plump arm.”

In Washington Daniels enjoyed an active social life, and participated in local Spiritualist circles. On Christmas Day 1863 he noted having attended a séance at which the medium Nettie Colburn presided. In March 1865 he described a gathering at the White House attended by First Lady Mary Lincoln and Daniels’s Spiritualist friends.

At some point in 1865 Daniels courted the noted Spiritualist Cora L. V. Scott Hatch (1840-1923), whom he married in Washington on Dec. 8, 1865. Thereafter both husband and wife often contributed to entries in Daniels’s diary. In some instances, Daniels recorded the substance of Cora’s séances, during which a spirit guide would speak through her. On Feb. 21, 1866, for example, Daniels described a gathering that included Clara Barton and Frances Gage, and at which Cora Daniels channeled the spirit of Theodore Parker, who answered questions about the current political situation. “Parker” predicted “difficulty between The President & Congress & ‘ere long war will exist”; not an inaccurate portrait of the relationship between President Andrew Johnson and Republicans in Congress.

The Daniels frequently lectured on Spiritualism and the rights of African Americans. They traveled the Spiritualist circuit for Cora’s demonstrations, and Nathan wrote newspaper reports and editorials of a largely political nature both with his own name and under the pseudonym “Viator.” A number of Daniels’s articles are preserved as newspaper clippings in a scrapbook included in the online collection.

But what of Daniels’s new job as register in Louisiana that served as his birthday present on May 10, 1867? Daniels’s last diary entry, May 29, 1867, recorded that he and his family had reached New Orleans that evening. “Darling wife is delighted with the country & I trust now that health and prosperity may be accorded to us.” It was not to be. A “Viator” article in the June 19, 1867 issue of the Rochester (New York) Express mentioned cases of cholera in New Orleans, and a fear that “the extremely filthy and unclean condition of our canals and suburbs, will generate an epidemic of yellow fever and cholera together.” Yellow fever did in fact break out in New Orleans that fall. Col. Nathan W. Daniels died of yellow fever on Oct. 2, 1867, and his young daughter Henrietta (born Sept. 27, 1866) died shortly after her father. Cora too became ill, but survived.

Cora Daniels married Col. Samuel F. Tappan (1831-1913) in 1869, but divorced him in 1876 to marry William Richmond, a member of her First Society of Spiritualists congregation in Chicago, Illinois. Cora must have forgotten, however, that Nathan Daniels’s diaries and scrapbook remained in the attic of the Tappan home in Manchester, Massachusetts. They were later discovered by C. P. Weaver, the great-granddaughter of Samuel Tappan’s sister. In 1998, Weaver published “Thank God My Regiment an African One: The Civil War Diary of Colonel Nathan W. Daniels,” which covered the January to September 1863 portion of the first volume of the diary. Weaver later donated to the Library of Congress the three volumes of Daniels’s diary, the scrapbook and summaries and transcripts she prepared of the unpublished diaries.

Just in time for Col. Daniels’s 180th birthday, these materials are all available online for the first time… “a very acceptable birthday present” for the nation.

May 8, 2016

Trending: The Mother of Mother’s Day

(The following article by Audrey Fischer is from the May/June 2016 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, soon to be available here. In the meantime, make sure to catch up on all our editions!)

One West Virginia daughter succeeded in memorializing mothers everywhere.

Anna M. Jarvis, 1864-1948, half length portrait, facing slightly right. Prints and Photographs Division

Greeting cards, flowers, candy, dining out—Mother’s Day is big business. Sales figures for the popular retail holiday topped $20 billion in the U.S. last year.

No one was more dismayed by the commercialization of Mother’s Day than Anna Jarvis (1864-1848), the woman who spearheaded the effort to memorialize mothers more than a century ago.

The ninth of 11 children, Jarvis was born in Webster, West Virginia on May 1, 1864. Her mother, Ann Reeves Jarvis, was a social activist who founded Mothers’ Day Work Clubs to combat poor health and sanitation conditions in the area. Only four of her children survived to adulthood. The others succumbed to such diseases as measles, typhoid fever and diphtheria, which were common in Appalachian communities. She also led her community’s effort to tend to wounded soldiers—the Blue and the Gray—during the Civil War.

After the war, Mrs. Jarvis continued to unite the deeply divided community by spearheading “Mothers Friendship Day” for the families of Confederate and Union soldiers. During one of her Sunday school lessons, she told the children that she hoped and prayed someone would devote a day to honor mothers.

The sentiment wasn’t lost on her daughter. Following her mother’s death on May 9, 1905, Anna began a campaign to honor her mother and mothers everywhere. Three years later, Andrews Methodist Episcopal Church in Grafton, West Virginia, was the site of the first official Mother’s Day celebration. The church has since been designated the “International Mother’s Day Shrine.”

The Mother With Children statue by William Douglas Hopen, outside the International Mother’s Day Shrine, at the Andrews Methodist Episcopal Church in Grafton, West Virginia. Photo by Carol Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

Jarvis continued to campaign for a national holiday. Her efforts culminated in legislation passed by Congress and signed by President Woodrow Wilson on May 9, 1914, that declared flags be flown “on the second Sunday in May as a public expression of our love and reverence for the mothers of our country.” The first national celebration was held on May 10, 1914.

A victim of her movement’s success, Jarvis spent much of the rest of her life railing against the increasing commercialization of the holiday all over the world. Her protests, which began first with florists, escalated to arrests for public disturbances. She even took First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to task for using the holiday to promote the health and welfare of women and children—a cause that her mother championed. Increasingly erratic, Jarvis died in a sanitarium in 1948.

FUN FACT

Mother’s Day is a singular possessive because Anna Jarvis intended for the holiday to honor “the best mother who ever lived, yours.”

MORE INFORMATION

Research Mother’s Day in Historic Newspapers

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers

carljungstudies.org

carljungstudies.org