Library of Congress's Blog, page 126

September 2, 2016

New Online: Presidents, Newspapers and Mobile Apps

Crowds fill the Walter E. Washington Convention Center during the 2014 National Book Festival. Photo by Colena Turner.

(The following is a guest post by William Kellum, manager in the Library’s Web Services Division.)

National Book Festival

The Library’s 16th Annual National Book Festival takes place on Saturday, Sept. 24, at the Washington Convention Center in Washington D.C., and we’ve updated our Mobile App and website with all the details. The app, available at no charge for iOS and Android users, contains the complete schedule of the dozens of author presentations, book-signings, special programs and activities. Users can plan and build their full day’s personalized schedule in advance, find their way around the center to their chosen activities, rate each presentation and more. The app also includes detailed information on updated security and safety procedures now for entry into the Washington Convention Center.

We’ve also launched a new podcast that features interviews with some of the award-winning authors from the 2016 National Book Festival. Episodes featuring Kristin Hannah, Carlos Ruiz Zafón, Joyce Carol Oates and Kwame Alexander are already available. You can also hear these interviews on iTunes.

Chronicling America

New on Chronicling America are 18th-century newspapers from the three early capitals of the United States: New York City, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. Nearly 15,000 pages have been added from The Gazette of the United States and related titles (New York, N.Y. and Philadelphia, Pa., 1789-1801); the National Gazette (Philadelphia, Pa., 1791-1793); and the National Intelligencer (Washington, D.C. 1800-1809). They have been added to the site in an expansion of the chronological scope of materials covered by the National Digital Newspaper Program. Check out the post from the Library of Congress blog for the full details.

Library Exhibitions

Eva Turner as Turandot. Photo by Fernand de Gueldre, 1936. Music Division.

On display in the Library’s Performing Arts Reading Room until Jan. 21, 2017, is “#Opera Before Instagram: Portraits, 1890-1955.” The photographs on exhibit in and in the companion online presentation represent a cross section of important singers who performed in the United States. Some artists are presented in formal attire, which would have been used for general publicity and concert appearances, and others are costumed as characters from their operatic repertoire. The photos are drawn from the Charles Jahant Collection in the Library’s Music Division, which contains nearly 2,000 photographs of opera singers from the 19th and 20th centuries, many of which are inscribed to him. Jahant began donating his collection to the Library in 1980, and it remains the largest iconographical collection held by the Music Division.

Presidential Papers

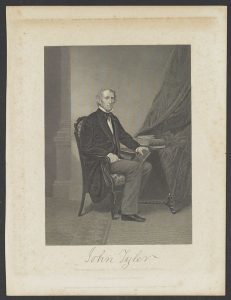

The Library continues to add to its online collection of presidential papers. Also new this month are presentations on John Tyler and Zachary Taylor.

Engraved portrait of President John Tyler, 1863. Manuscript Division.

John Tyler, the 10th president of the U.S. (1841-1845), was acutely conscious of the legacy he would leave upon his death, carefully collecting papers documenting his life and work. Following his 1862 death, the Tyler home – Sherwood Forest in Charles City County, Virginia – was entered by Union soldiers and others. Papers that were reported to be present in the house were subjected to ransacking, looting and destruction. Tyler’s son Lyon Gardiner Tyler (1853-1935) sought out materials that might still be extant, contacting family friends and known recipients of Tyler correspondence. He recovered part of an autograph collection and letters, or copies of letters, written by his father to friends and political contemporaries, and sold the original documents and copies he had collected to the Library of Congress in 1919. The online collection is made up primarily of correspondence, including letters and copies of letters to or from Tyler (1790-1862), a governor and U.S. representative and senator from Virginia, who served as vice president under William Henry Harrison before becoming the 10th president of the United States upon Harrison’s death in 1841. Also included are letters to and from Julia Gardiner Tyler, Tyler’s second wife, and members of the Gardiner family, and “autograph” letters by others, which were collected by Tyler. Also included in the presentation is an illustrated chronology of key events in Tyler’s life.

The Zachary Taylor Papers Collection contains approximately 650 items dating from 1814 to 1931, with the bulk from 1840 to 1861. The collection is made up primarily of general correspondence and family papers of Taylor (1784-1850), with some autobiographical material, business and military records, printed documents, engraved printed portraits and other miscellany relating chiefly to his presidency (1849-1850); his service as a U.S. Army officer, especially in the 2nd Seminole Indian War; management of his plantations; and settlement of his estate. The online presentation also includes an illustrated timeline of Taylor’s life.

Pershing and Patton Papers

The John J. Pershing Papers Collection features the diaries, notebooks, and address books of John Joseph Pershing (1860-1948), U.S. army officer and commander-in-chief of the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I. Part of a larger collection of Pershing papers available for research use onsite in the Library’s Manuscript Reading Division, the entire collection spans the years 1882-1971, with the bulk of the material concentrated in the period 1904-1948. It consists of correspondence, diaries, notebooks, speeches, statements, writings, orders, maps, scrapbooks, newspaper clippings, picture albums, posters, photographs, printed matter and memorabilia.

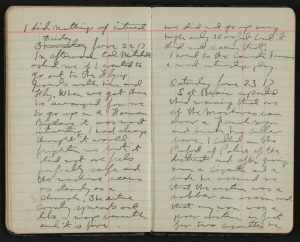

This page from Patton’s diary of June 22, 1917 describes his first bi-plane flight, piloted by William Mitchell. Manuscript Division.

The George S. Patton Papers: Diaries, 1910-1945 online collection features the diaries of U.S. army officer George S. Patton (1885-1945). Like Pershing, the Patton diaries are part of a larger collection of Patton papers available for research use onsite in the Manuscript Division. The entire collection spans the years 1807-1979, with the bulk of the papers concentrated from 1904 to 1945. The collection documents Patton’s military career, including his attendance at West Point, 1904-1909; his service on the Mexican border as a member of John J. Pershing’s Mexican Punitive Expedition, 1916-1917; his service as an aide-de-camp to Pershing and later as a tank commander in World War I, 1917-1919; and his military career from 1938 to 1945. The majority of the papers chronicle Patton’s World War II service and his success as one of America’s most skillful combat commanders of armored troops.

Collection Upgrades

Finally, we continue to gradually upgrade and migrate older collections to new presentations – the latest upgrade from our legacy American Memory project is Pioneering the Upper Midwest: Books from Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, ca. 1820 to 1910. The collection portrays the states of Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin from the 17th to the early 20th century through first-person accounts, biographies, promotional literature, local histories, ethnographic and antiquarian texts, colonial archival documents and other works drawn from the Library’s general collections and Rare Books and Special Collections Division. The collection’s 138 volumes depict the land and its resources; the conflicts between settlers and Native peoples; the experience of pioneers and missionaries, soldiers and immigrants and reformers; the growth of local communities and local cultural traditions; and the development of regional and national leadership in agriculture, business, medicine, politics, religion, law, journalism, education and the role of women.

August 31, 2016

Headlines from America’s Earliest Days

Coverage of the inauguration of George Washington. Gazette of the United-States., May 02, 1789. Chronicling America.

Want to read how an 18th-century newspaper covered the inauguration of George Washington? How about learning what issues divided Congress in the early 1800s?

Going back into early American history is now possible due to new digital content that has been added to Chronicling America, the open access database of historic U.S. newspapers that is part of the National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP).

The newly available digital content is from 18th-century newspapers from the three early capitals of the United States: New York City, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. At nearly 15,000 pages total, these early newspapers from the earliest days of the country are part of the database because of an expansion of the chronological scope of NDNP. The program is expanding its current time window of the years 1836-1922, to include digitized newspapers from the years 1690-1963. The expansion will further the program goal of capturing the richness and diversity of our nation’s history in an open access database, which anyone can use.

Two of the early newspapers were established as national political publications. The Gazette of the United States (1789-1800) advocated a strong monarchical presidency and loyalty to the federal government. In opposition, the National Gazette (1791-1793), as the voice for the Republicans or Anti-Federalists, promoted a populist form of government.

The National Intelligencer (1800-1809) was the first newspaper published in the City of Washington and the first to document the activities of Congress. It recorded in great detail the actions of the young national legislature.

NDNP is a partnership among the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Library of Congress and participating states. NEH awards grants to state libraries, historical institutions and other cultural organizations that allow them to select historic local newspapers to be preserved in digital form. The states contribute information on each newspaper title and its historical and cultural context. To date, more than 11 million pages of historic newspapers are available on Chronicling America.

Only public-domain newspapers may be selected—that is, either those published before 1923 or those published between 1923 and 1963 and not under copyright. Henceforth, all state and territorial partners will be able to select newspapers from the expanded date scope, provided they can prove the publications are in the public domain.

Chronicling America presents pages from the past full of stories that provide historic glimpses of American life, culture, government, politics and more. Read up on widely covered topics of their time or check out previous blog posts highlighting the collection.

August 24, 2016

World War 1: Bad Romance — Gibson’s Chilling Personification of War

(The following is a guest post by Katherine Blood of the Prints and Photographs Division.)

[image error]

“And the Fool, He Called Her His Lady Fair,” by Charles Dana Gibson. 1917. Gift of Charles D. Gibson and Kay Gibson, 2013. Prints and Photographs Division.

Illustrator Charles Dana Gibson was already a celebrity when tapped in April 1917 to lead the federal government’s Division of Pictorial Publicity — an arm of Woodrow Wilson’s Committee on Public Information. He was enlisted by Committee head George Creel, who believed that visual art could provide a unique service in winning the hearts and minds of the American public. And not just any art — nothing less than the best art by the best artists was sought to bolster recruitment, fundraising, service by women and civilians and troop support in myriad forms including contributions for camp libraries. When Gibson famously urged fellow artists to “Draw ‘till it hurts!” in support of America’s war effort, he was addressing such luminaries as James Montgomery Flagg, Howard Chandler Christy and Edward Penfield, to name just a few of the division’s more than 300 participants.

[image error]

The weaker sex. By Charles Dana Gibson, 1903. Prints and Photographs Division.

Among Gibson’s most enduring creations was the iconic Gibson Girl, who began appearing in the 1890s. She embodied the “New Woman” who was active and independent, intelligent and beautiful. But a very different kind of Gibson woman commanded my attention when I had the chance to co-curate the exhibition “World War I: American Artists View the Great War” with my colleague Sara W. Duke. In a vivid satire called “And the Fool, He Called Her His Lady Fair,” Gibson presents war as a woman who is an unsettling hybrid of menace and allure, the seeming antithesis of the fresh, youthful and wholesome Gibson Girl ideal. At the same time, her casual dominance over a male companion echoes a recurring theme in Gibson’s work in which women are anything but the weaker sex. Here, she is a bored femme fatale, dripping with disdain. Contemporary audiences would have recognized her would-be partner as a sardonic incarnation of Germany’s Supreme War Lord Kaiser Wilhem II. Gibson presents him as a kind of visual double-entendre, clutching his chest in a way that might suggest amorous suitor or heart attack victim. His neglected gifts of roses, pearls and coins are strewn around the room. Among them, an Iron Cross medal lies ignored on the couch — suggesting that Wilhelm has lost or squandered his valor.

[image error]

Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany. Prints and Photographs Division.

The lady is richly-dressed and thin to the point of emaciation. Her skeletal hand, raised in a gesture of languid rejection, might prompt viewers to expect a cigarette. Instead, the smoke evokes the sinister presence of poison gas in a parlor that is also a battlefield. In case we were in any doubt, a bottle of wine on a small table near her knees bears a skull and crossbones, underscoring that this lady is a deadly creature. The wine drips from the table in a viscous, blood-like way and pools at her feet.

Martha Kennedy, curator for the Library’s 2013 exhibition “Gibson Girl’s America” and an aficionado of the archetype’s evolving persona points out that this theme must have haunted Gibson during the interwar years: “He appears to have re-worked it in a World War II era painting in which he depicts a harlot holding a mask in one hand while raising the other to reveal her gaunt, sunken face, causing Hitler, like Kaiser Wilhelm II, to jump back in consternation.” Variations on this theme can also be connected more broadly back to 15th-century “Dance of Death” traditions in which Death confronts the living regardless of rank or merit. Gibson’s razor-sharp allegory still packs a punch — offering today’s viewers a hall-of-mirrors meditation on the nature of power, gender dynamics, war, and wisdom.

World War I Centennial, 2017-2018: With the most comprehensive collection of multi-format World War I holdings in the nation, the Library of Congress is a unique resource for primary source materials, education plans, public programs and on-site visitor experiences about The Great War including exhibits, symposia and book talks.

August 22, 2016

Rare Book of the Month: “I am Anne Rutledge…”

(The following is a guest blog post written by Elizabeth Gettins, Library of Congress digital library specialist.)

“Anne Rutledge.” [words by] Edgar Lee Masters; music for voice and piano by Sam Raphling. 1952. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

This week, we not only celebrate the birthday of author Edgar Lee Masters (Aug. 23, 1868) but also observe the untimely death of Ann Rutledge (Aug. 25, 1835), who figured in his best-known work.Masters spent his childhood in Lewistown, Illinois, a town near Springfield where Abraham Lincoln lived from 1837-1847. Initially, Masters practiced law for a living, but in 1898 he branched out, realizing his true life’s calling by publishing his first work, titled “A Book of Verses.” He then went on to draw from his childhood experiences of life with people in a small Illinois town for his most beloved work, “Spoon River Anthology,” published in 1915. It is a collection of monologues from the dead in an Illinois graveyard in the fictional town of Spoon River. The characters that Masters chose to draw on for his inspiration are all located in the general area that Lincoln inhabited for much of his young life, including Lincoln’s “first love,” Anne Rutledge.

Master’s entry for Ann Rutledge speaks of unrealized love between her and Lincoln. She is generally referred to as Lincoln’s first love, although many debate whether the two were actually ever a pair. The story goes that Rutledge was betrothed to John MacNamar and that Rutledge and Lincoln met and fell in love while he was away. Purportedly, she made plans to break her engagement to MacNamar upon his return. The plans never came to fruition, as a typhoid outbreak hit in 1835 killing Rutledge at age 22.

Edgar Lee Masters. July 30, 1924. Prints and Photographs Division.

Rutledge’s actual burial site is in Petersburg, Illinos, and her gravestone features Master’s work:

Out of me unworthy and unknown

The vibrations of deathless music:

“With malice toward none, with charity toward all.”

Out of me the forgiveness of millions toward millions,

And the beneficent face of a nation

Shining with justice and truth.

I am Ann Rutledge who sleeps beneath these weeds,

Beloved in life of Abraham Lincoln,

Wedded to him, not through union,

But through separation.

Bloom forever, O Republic,

From the dust of my bosom!

This songsheet, titled “Anne Rutledge,” is part of a larger work inspired by “Spoon River Anthology.” The music for this item was composed by Sam Raphling and was published by Musicus around 1952.

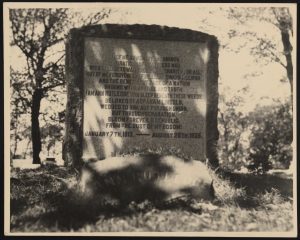

Ann Rutledge grave, Petersburg, Illinois. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

The songsheet, as well as the photograph of Rutledge’s gravesite, are items from the Alfred Whital Stern Collection of Lincolniana. Alfred Whital Stern of Chicago presented his collection to the Library in 1953. Begun by Stern in the 1920s, the collection documents the life of Abraham Lincoln through writings by and about Lincoln, contemporary newspapers, sheet music, broadsides, prints, stamps, coins, autograph letters and a large body of publications concerned with slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction and related topics. The collection includes Lincoln’s own scrapbook of the 1858 political campaign against Stephen A. Douglas, numerous campaign biographies prepared for the 1860 presidential election, printed materials relating to the assassination and funeral, and a Lincoln life mask in bronze by Leonard Volk.

Probably the single most famous Lincoln manuscript in the collection is the letter to Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, dated Jan. 26, 1863, placing him in command of the Army of the Potomac. Since Stern’s death, the collection has continued to grow through the provisions of an endowment established by his family and it now numbers over 11,100 pieces.

August 16, 2016

Letters About Literature: Dear Anne Frank

We wrap up our Letters About Literature series with the second tie-winning National Honor Award letter for Level 3 (grades 9-12). The national reading and writing program asks young people in grades 4 through 12 to write to an author (living or deceased) about how his or her book affected their lives. Winners for 2016 were announced in June.

Research shows that students benefit most from literacy instruction when they are engaged in reading and writing activities that are relevant to their daily experiences. Nine students were given national recognition and come from all parts of the country. You can read all the winning letters here, including the winning letters from previous years.

This letter comes to us from Violet Fearon of New York, who wrote to Anne Frank, author of “The Diary of a Young Girl.”

Dear Anne,

There are some books you read that you like, and some that love, and some that you adore. And then there are books that are separate from the rest – books that burrow down deep into your consciousness and stay there, festering. Books that change the way you think, the way you act, the way you see the world, that change who you are. You don’t come across too many of these books in a lifetime. The rare few that you do, I believe, are typically read early in life. The young mind is more open to suggestion. And your book, Anne, is even more unusual. Because you never really intended to write a book, did you? Let alone one that would shape the world. Then again, I suppose I never really intended to read your book, let alone be shaped.

It begins at age seven. I found you on my parent’s bookshelf. I remember running my hands across all the spines – I’d just read a fantasy novel where the girl did that, and the one that stuck out taught her how to cast spells. All the other books were big and serious, no pictures, no colors, just thin pages and tiny text. Yours was small – it could almost fit in a coat pocket. It had a picture of you on the cover. You were pretty. Not pretty in a Marilyn Monroe, Scarlett Johansson, Hollywood way – that would’ve scared me. You were pretty in the nice kind of way. You smiled with your eyes. I looked behind me, pretended I was committing some unspeakable crime for the sake of excitement, then stuffed your little book under my shirt and ran upstairs to my bedroom.

Let me preface this by saying: I didn’t know. Almost everyone who reads your diary, I think, goes into it with some knowledge of how it all ends, some sense of foreboding. They interpret every word in that context, tense up at every sign of something going wrong. I didn’t know what was waiting in the last few pages. But this is what I did know: You had dark hair, just like me. You wanted to be a writer, just like me. You felt frustrated by the way people thought of you as some frivolous little girl, just like me. On the back of your book, it said you were Jewish; my Mom was Jewish, but my Dad wasn’t. We hardly ever went to temple, and I was starting to feel like I didn’t believe in God. Did that count? I wasn’t sure. You had one older sister, though, just like me – and she was three years older than you, just like mine. Given that I was emerging from an age when having the same color shirt on the playground was enough reason to make a new best friend, these correlations fascinated me. So I read on.

You were older than me-thirteen. It seemed very exotic – even Lily, my sister, was only ten. The cover said “The Diary of a Young Girl,” but that didn’t make any sense to me; a young girl was a girl younger than me – three, four, five. Once you added “teen” to your age, which meant you were like an adult. You became six feet tall and looked like Barbie and were in control – “teen” meant you knew things.

Your diary is touted as a historical document, as a cultural landmark, as a fresh perspective – and it is. But it is also engrossing. All the little private victories and failures, the speeches about mothers and sisters and friends – it amazed me. It amazed me that the people in history were real people. That everyone, everyone who had ever lived, had feelings and thoughts just like mine. This still amazes me. I had a vague idea of Hitler and the Nazis, faded tidbits I’d picked up here and there. A few elderly relatives on my mother’s side had bad things happen to them in The War – I could hear the capitals, when people talked about it, the slight emphasis on “the.” I knew it was impolite to ask them about it, though I was dying to. I had never considered that when they’d lived through The War, they weren’t old. The thought of my grandparents as teenagers made me uncomfortable, like some immutable law of the universe was being broken.

But you weren’t my grandparents. You were like me. I wondered if you were old now. I kept on reading. It was sometimes a struggle – most of the books I read at that age involved talking animals or friendly orphans. I would read a few entries every night, a private ritual before I went to sleep. I noticed the history behind the stories – the mentions of Hitler, of fighting, of death. But my main focus was on the drama: disputes over rations, arguments over whose turn it was to use the bathroom, musings about cats. The Secret Annex seemed almost magical to me, something terrifically exciting. If I ever had to live in an attic, I decided, I would start a diary. You’d started yours before going into hiding, though – so I began one just in case. As I continued, I kept track of how much I had left. The pages held down by my right thumb dwindled – The War , I thought , must almost be over. I wondered how you were going to end it. I imagined what it must be like – to step outside for the first time in three years, to breathe in fresh air, to feel the sun. I hoped you would come back to make a final entry talking about all that – but then, I reasoned, there would be so much more to do, and less time to write , once you got back to normal life.

I don’t really need to tell you how it ends, do I? But I will. There is no end. Not really. The last entry talked about your duality – the flippancy you show around others, the more pensive person you could be without society. Then, “Yours, Anne M. Frank,” and that was it. There was an afterword; it was just a page long. It traced the paths of the eight in the Secret Annex – from Amsterdam, to Westerbork, to Auschwitz. I didn’t know how to pronounce “Auschwitz” – in my head, it was an ugly word, Ayoo-skah-wizz. Van Daan, gassed; Peter, the death march; Edith, starvation and exhaustion. You and Margot went to Bergen Belson, where you both died of typhus. Typhus. It wasn’t Mengele or firing squads or Zyklon B – it was disease. You were buried in a mass grave. For some reason, I fixated on that – to not even have a grave seemed a minor injustice that, on top of all the others, brought the whole situation to a breaking point. Back then reality and fiction were intertwined , but I knew enough to know that you had existed in a way that the girl that found the magic spell book hadn’t. I hunched over in bed, and I stared at your eyes, and I cried for a long time. I think that must have been the first time I ever cried about something other than scraping my knee or going to school or being cranky. The enormity of non-fiction, of reality, pressed down on me; this had happened. It had happened before I was born, and it will keep on “having happened” after I die, and there’s nothing anyone can do about it. The past is the past. There was no use telling my parents. Maybe there are some things even parents can’t solve. I don’t know.

Then I forgot. Well, not forgot, as such – but life happens. Things slip from the conscious, if not the subconscious. I woke up the next day still upset, but not in tears; I ate breakfast. Over the course of a week or so, your book found its way back to my parent’s room, and I went to school and came home and brushed my teeth twice a day and started reading Harry Potter.

The next time I remembered you was brief – I was twelve, in sixth grade. We read a picture book about you on Holocaust Remembrance Day. Before we began, the woman reading the book told us all, this is a very sad story, and we all have to learn about it so it never happens again. All the pictures were watercolors, painted in blacks and whites and browns – a girl standing in the rain, a girl staring out a window, a girl in a train cart. I remember thinking that wasn’t right at all, was it – your life was many things, but it was never colorless.

At the end, the inevitable happened, as I knew it would. The woman said you were fifteen when you died. She and my teacher exchanged a glance. It was only three years away, but fifteen seemed just as far away as when it did when I was seven – thirty-six long months was time enough to get taller and know everything. I realized, though, that I was now almost at the age when you went into hiding. It was like two paths were splitting.

I came home and re-opened your book. It was the same copy. There you were, on the cover, still smiling, still unchanged. This time I read the introduction and skimmed the pages, quickly flipping past months and years. Now I understood what represents the lost potential meant. “Lost potential” means that when you died, all the novels you might have created, all the articles you might have written, all the people you might have touched with even more words, died with you. “Represents” means that this loss, this story, is just one of millions; more than millions – every child, every adult, every person ever killed before they got to do what they should have been able to.

I understood, then, that your book, the one you never meant to write, is one of the most widely-read pieces of nonfiction in the world. Everyone from John F. Kennedy to Eleanor Roosevelt has referenced you; you are the poster child of the Holocaust, of all holocausts; you are probably the most influential teenager to ever live. I know all this, and it all is true – you’re a symbol. You are, but you’re also just Anne, who spent her days looking out attic windows and wishing she could play hopscotch with the Christian girls. These two identities seemed to conflict in my mind – I thought some more, then put away your book once again. Is it possible to be an international symbol and human being at the same time? I don’t know.

But all that is over. Your story is long gone. I am sixteen now. I haven’t thought of you much in four years – I can’t. But last night, I was lying in bed, surfing online, and I came across your Wikipedia page- little numbers beneath your picture: June 1929 – February 1945. I counted in my head, then I counted again. I have passed the point. You were younger than me when you died. I’m sixteen, and I’m still short, and I still don’t look like Barbie. I still don’t know everything.

I closed the computer and lay in the dark. I couldn’t fall asleep because it was too loud in my head, a single thought, repeating: I am not a grown-up. I am not a grown-up. I am not a grown-up. That look the woman and the teacher exchanged – that is the look adults give each other when they talk about children dying. I am not a grown-up. Is this how getting older works? That you have this fantastic idea of what you will be like at 10, at 16, at 30 – but when you arrive, you still feel the same? I don’t know.

Let me tell you something: when asked about reading your diary, your father said, “I had no idea of the depths of her thoughts and feelings.” Some people say, She was his daughter. They were locked together for years. How could he not have known? But that is not unusual. We all have our innermost selves, the ones we keep deep inside us that we hide from prying eyes. Everyone-you taught me that.

You taught me that for each of the 12.5 million Africans shipped to this country in the Triangular Trade, there was a story. That every Armenian killed under the Ottoman Empire had innermost musings. They tell us we learn about you so it never happens again – but it has already happened again. Every child murdered in Darfur, in Rwanda, in Cambodia, is a lost adult, a lost world, a lost universe. It’s like that video, the one narrated by Carl Sagan that shows you that vastness of the galaxies, then zooms in on a picnicker’s hand and shows you the vastness of cell walls and protons and quarks. You can zoom in however far you can take. I’m not aware of this all the time. I’m not aware of it most of the time. But sometimes – sometimes I am able to look up from the textbook, from the statistics and body counts – and remember you.

Remember that every human being is, essentially, a human being; that there is so much two eyes can say. Maybe you wouldn’t have written novels or articles, or anything of more importance than your diary. Who can say? Maybe you would’ve just lived a quiet life and had a little cottage and two children, and turned into an old woman around whom seven years olds have to remember not to ask about The War. That would’ve been enough. More than enough. I don’t know.

Let me tell you something else: the man who discovered you, the SS officer – his name was Karl Silberbauer. He died a long time ago, too. HIs Wikipedia picture is grainy; he had deep set eyes and puffy cheeks. Your father testified at his trial in defense of him, telling the disciplinary hearing that he had simply been doing his job as a policeman. Otto said, “The only thing I ask is not to have to see the man again.” I don’t think I can even imagine the strength that took. When Silberbauer found the Secret Annex, he told your father: “You have a lovely daughter.” After reading this, my first thought was, “Lovely enough to kill, apparently.” But after that I just felt a little bad for him. Maybe I shouldn’t have. Maybe there are enough people out there to feel bad for without looking up long-gone Nazis. Still – did he have innermost thoughts, too? I don’t know.

This is what I do know: I will be seventeen soon. From then on, the gap between us will just keep on widening. One day I will think about you again, and I really will see you as a “young girl.” I guess that’s a good thing. I can’t be like you – forever an adolescent, frozen in old photographs, timeless. We age. This has gotten long, longer than I planned, longer than it has to be. Because this is all I need to say: thank you.

Violet Fearon

August 11, 2016

Curator’s Picks: Signature Sounds

(The following is from the July/August 2016 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

Matt Barton in the Library’s Motion Picture and Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division discusses some of the nation’s most iconic radio broadcasts.

DATE OF INFAMY SPEECH

DATE OF INFAMY SPEECH

President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed a Joint Session of Congress on Dec. 8, 1941—one day after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The president referred to Dec. 7 as “a date which will live in infamy.” Within an hour of the speech, Congress passed a formal declaration of war against Japan and officially brought the U.S. into World War II. “In his nine-minute speech, the president sought not only to rally the nation, but to provide the most accurate picture possible of the extent of the attacks made in the Pacific to that point, countering rumors but also conveying the seriousness of the situation.”

Weltbild Publishing Company, Prints and Photographs Division

MARIAN ANDERSON SINGS

Denied the right to sing at DAR Constitution Hall because of her race, contralto Marian Anderson performed an Easter Sunday concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on April 9, 1939. The event drew an integrated audience of 75,000, including members of the Supreme Court, Congress and President Roosevelt’s cabinet. “News photos and newsreels of this event have become iconic, but millions of Americans experienced the radio broadcast first, live and in real time.”

Prints and Photographs Division, courtesy of the NAACP

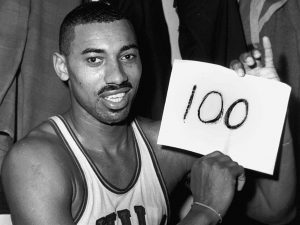

WILT CHAMBERLAIN’S 100-POINT GAME

WILT CHAMBERLAIN’S 100-POINT GAME

In 1962, Philadelphia Warriors center Wilt Chamberlain shattered the NBA record by scoring 100 points in a single game. The game was broadcast only by a Philadelphia radio station and rebroadcast later that night. “Those broadcasts were lost but fortunately two fans recorded key portions of those broadcasts. The NBA eventually acquired both recordings.”

Prints and Photographs Division

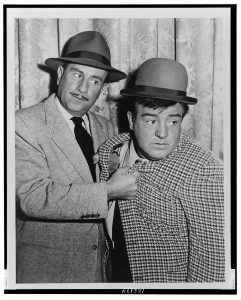

WHO’S ON FIRST?

Comedians Bud Abbott and Lou Costello first performed their now- legendary baseball sketch for a national radio audience on “The Kate Smith Hour” in March 1938. This broadcast is now lost, but in response to popular demand, the duo gave an encore performance later in the year, which survives.

New York World- Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, Prints and Photographs Division

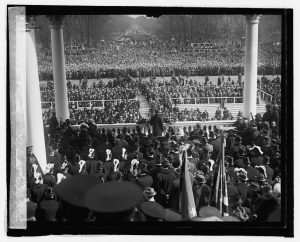

COOLIDGE INAUGURAL ADDRESS

COOLIDGE INAUGURAL ADDRESS

Calvin Coolidge made history at his second inauguration on March 4, 1925. “It was the first time an inauguration was broadcast nationally on the new medium of radio, and it was carried on 30 stations nationwide.”

National Photo Company Collection, Prints and Photographs Division

All of the above radio broadcasts were selected for inclusion in the National Recording Registry, which ensures their long-term preservation.

August 10, 2016

World War I: When Wurst Came to Worst

(The following post is by Jennifer Gavin, senior public affairs specialist at the Library of Congress.)

In the United States, a century ago, there were more than 8 million citizens of German origin or with German ancestry – the largest single group among those of foreign birth or ancestry, but still less than 10 percent of the total U.S. population of over 102 million. Like other immigrant groups, they were scattered all over the country, with concentrations in many big cities, and like other immigrant groups, they “had their ups and downs” as they interacted with neighbors of different backgrounds.

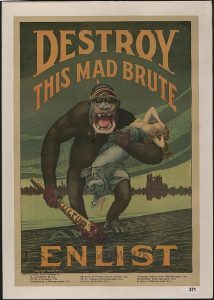

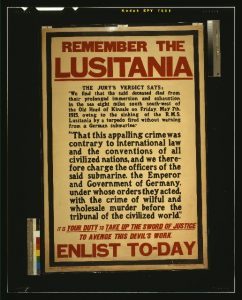

Destroy this mad brute Enlist – U.S. Army. Prints and Photographs Division.

One of the bigger “downs” followed the opening of World War I (the art of that war is the subject of a current Library of Congress exhibition). It was a German war of aggression, and much U.S. public sentiment turned against Germany and Germans, even as then-President Woodrow Wilson tried to keep the U.S. out of the war. This reached a fever pitch with the German U-boat sinking of the British luxury liner “Lusitania,” causing the loss of 1,198 lives including those of 123 Americans. The public – both in England and the U.S. – was shocked that the German war machine would torpedo a passenger ship rather than sticking to warships or merchant-marine vessels.

When that sentiment turned, and particularly after the U.S. got into WWI, it suddenly became difficult to be German. Schools stopped offering classes in the language, once common. Music by German composers such as Mendelssohn and Wagner ceased to be performed. Many Americans with German surnames anglicized them. There were even efforts to rename foods of German origin – sauerkraut became “liberty cabbage,” for example.

The anti-German feeling increased stateside, where former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt denounced “hyphenated Americans,” meaning German-Americans and Irish-Americans, the two largest groups of immigrants in the country. President Wilson shared that view, saying “Any man who carries a hyphen about with him carries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of this Republic whenever he gets ready.”

Many German-Americans proved their loyalty by joining U.S. military service and fighting “the Huns” in Europe. Among them was my grandfather, Phil Oberhauser. He was a corporal in the U.S. Army in France during the American engagement there, seeing service in the battles of Chateau Thierry, Verdun, and the St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne offensives. He was mustard-gassed and suffered from problems with his lungs and teeth for the rest of his life. But he made it out alive, became a traveling paper-products salesman and married a girl who first approached him on roller-skates. She was working at a telegraph office in Omaha – an office so large the staff skated from the telegraph operators on one end of the building to the public counters at the other.

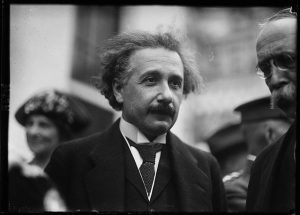

Albert Einstein, Washington, D.C. Prints and Photographs Division.

After the war ended, anti-German sentiment settled down, until the return of German militarism under Hitler. However, Germans fleeing the Third Reich were welcomed into the U.S., and many became celebrated (if sometimes controversial) new U.S. citizens, including many scientists – physicist Albert Einstein, rocket scientist Werner von Braun and chemists Otto Loewi and Max Bergmann – and other celebrated artists and intellectuals.

World War I Centennial, 2017-2018: With the most comprehensive collection of multi-format World War I holdings in the nation, the Library of Congress is a unique resource for primary source materials, education plans, public programs and on-site visitor experiences about The Great War including exhibits, symposia and book talks.

August 9, 2016

Letters About Literature: Dear Marie Lu

We continue our spotlight of letters from the Letters About Literature initiative, a national reading and writing program that asks young people in grades 4 through 12 to write to an author (living or deceased) about how his or her book affected their lives. Winners for 2016 were announced in June.

Nearly 50,000 young readers from across the country participated in this year’s initiative, which aims to instill a lifelong love of reading in the nation’s youth and to engage and nurture their passion for literature

There was a tie for the national honor award for Level 3 (grades 9-12). Following is one of the winning letters written by Macoy Churchill of Wyoming, who wrote to Marie Lu, author of “Legend.”

Dear Marie Lu,

Being a criminal comes with a certain looming paranoia, even for the craftiest of criminals. You have to plan out your every move, never missing even the smallest of details, and if you slip up the law will not blink an eye at throwing you into a cell you worked so hard to avoid. Just like Day, my heart was the very thing that caused me to end up with undesirable metal cuffs around my wrists, and the foreign sound of a juvenile cell door clicking close behind me to become routine. My inability to let my brother take my possession charges for me made me feel like Day, bounding from the room of his childhood home, to his imminent capture. My actions metaphorically put my family, especially my mother, in the direct line of fire. I read “Legend” and realized that I was stuck, incarcerated, thinking of the harm my actions had on my family, just as Day in his cell.

An overwhelming interest started to overtake me when I started to make connections between my criminal actions and Day’s. I would remember sitting in my car overlooking my house envisioning my family’s actions while they resided comfortably inside the house. Overtaken by substance, I felt like someone else watching over my family, like I couldn’t go in because of the possible repercussions it would have on my family. Day knew exactly the same thing would happen if he entered his childhood home. Although our situations were different, they were the same. We watched over our family for comfort, but couldn’t be with them because we were different. The son we once had been was overtaken by a life of crime. Although we wanted the situation to change, we knew it would never be the same.

Day let his heart destroy his flawless criminal history to avoid a simple argument with Tess, and I did the same thing. I was a good criminal, and I knew every step to take to avoid being caught. When I asked my brother if we should have taken precautions to avoid being caught, he said it would take too much time. I knew what we had to do, but to avoid an argument with my brother, I decided to take my chances. Day did a very similar thing. He knew the trouble in saving a stranger, but to avoid the solemn eyes of Tess, he took his chances. We decided to roll the dice to avoid having to look in the eyes of our upset loved ones, and inevitably it was our downfall. Criminals cannot have hearts, or good intentions. In order to protect ourselves, we have to hurt our loved ones. When I gained this knowledge from your book, I felt better as I lay in my cell; I knew hurting my loved ones wasn’t worth a flawless criminal history and so did Day.

The connections I made to “Legend” caused me to lie stunned in my overly frigid cell, completely stunned. This book taught me lessons about my criminal life when I didn’t even take a step. It showed me exactly where my criminal conduct would take me when I refused to see the enclosed walls around me. “Legend” caused me to open my eyes to the inevitable capture of every criminal regardless of his/her wit, effort, and will to avoid incarceration. Unlike Day I don’t have an exquisite lover like June to ensure my freedom. My capture is only escaped through the time given by the judicial system. As I flipped the last page, I knew that letting my brother take my charges would be equivalent to John taking Day’s place on the firing line. I would have to allow my criminal consequences to fall on my family’s shoulders, then my loved ones and society would have to suffer.

Only through “Legend” was I able to see this fact. Before I dove into this book, I was blind to the cell I was in, the situation that only I put myself into, and the metaphorical massacre of my family’s emotions. Through “Legend” I became aware of my profound need to change. For that I could never thank you enough.

Macoy Churchill

You can read all the winning letters here, including the winning letters from previous years.

August 8, 2016

Library in the News: July 2016 Edition

In July, the Library of Congress was widely in the news with the U.S. Senate’s vote to confirm Carla Hayden as the 14th Librarian of Congress. She will be both the first woman and first African American to serve in the position.

“Hayden will be the first Librarian of Congress appointed during the internet age – and the first librarian who seems to understand its power,” wrote Robinson Meyer of The Atlantic.

“Libraries are usually seen as repositories of history, not places where history is made. But yesterday was an exception as the Senate moved to confirm the nation’s next Librarian of Congress—one who is widely expected to change the institution and the role forever,” said Erin Blakemore for Smithsonian.com.

“An administrator so dedicated to bringing the library to the people that she kept everything open during last year’s unrest in Baltimore will become the first black American and first female librarian of Congress,” reported Melanie Eversley of USA Today.

The announcement made many more national and regional news including The Baltimore Sun, Time, The Washington Post, Slate Magazine and American Libraries.

In other big name news, the Library also announced Smokey Robinson as the next recipient of the Gershwin Prize for Popular Song.

“Whether he was singing his own compositions or writing for other artists, Smokey Robinson was instrumental in shaping the Motown sound that changed American popular music in the 1960s,” wrote Ben Nuckols for the Associated Press. “Now, his accomplishments have won him the pop music prize from the national library.”

“As a singer, songwriter and producer, Mr. Robinson, 76, has a musical résumé few can match,” said Joe Coscarelli of the New York Times.

Library experts continue to be featured in The Washington Post’s series of “Presidential” podcasts. New presentations are on Teddy Roosevelt and Benjamin Harrison. In fact, the presentation on William Howard Taft rounds out the Library’s contribution to the series, which also noted the Library as “such an incredible resource.”

And, finally, Upworthy included the Library of Congress in its list of nine “stunningly beautiful libraries to see before you die.

August 5, 2016

New Online: More Presidents & Newspapers

(The following is a guest post by William Kellum, manager in the Library’s Web Services Division.)

July was a relatively quiet month for the Library’s websites, highlighted by the long-planned retirement of THOMAS, covered in this excellent blog post from the Law Library’s In Custodia Legis blog.

New in Manuscripts

The William Henry Harrison Papers have recently been added to the Library’s online collection of presidential papers. This collection joins eight other presidential collections online, including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and Abraham Lincoln.

The Harrison papers contain approximately 1,000 items dating from 1734 to 1939, with the bulk dated from 1812 to 1841. Harrison (1773-1841), an army officer, representative and senator from Ohio, served as the ninth president of the United States. His collection includes a letterbook, 1812-1813, correspondence and military papers stemming mostly from his military and political career in the Northwest Territory, his service in Indian wars and the War of 1812, his time as territorial governor of Indiana Territory (1800-1812), and his role as Whig Party candidate in the unsuccessful 1836 presidential bid and the successful 1840 election. The latter led to his abbreviated presidential term, cut short by his death one month after his inauguration.

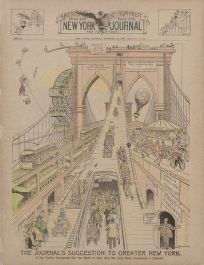

Cover image from the New York Journal, October 24th, 1897

New in Newspapers

Many users know of our Chronicling America site that features historic American newspapers from 1836-1922. The Library is also busy digitizing additional newspapers of historic significance – newly added is the New York Journal (and related titles) Collection, covering William Randolph Hearst’s papers from 1896-1899. The New York Journal is an example of “Yellow Journalism,” where the newspapers competed for readers through bold headlines, illustrations and activist journalism. The paper infamously reported on and influenced events like the Spanish-American War. The Sunday editions contained additional supplements: American Women’s Home Journal, American Magazine and the American Humorist, which included the “Yellow Kid” comic strip. These supplements featured colorful layouts and covered sporting events, pseudoscience and popular culture, such as the bicycle craze of 1896.

We’ve also added 152 issues of the New York Herald – these newspapers don’t have their own collection presentation, but you can access them in our search.

Exhibition Update

The extensive online exhibit The Mexican Revolution and the United States in the Collections of the Library of Congress is now available in a Spanish language version. The exhibit tells the dynamic story of the complex and turbulent relationship between Mexico and the United States during the Mexican Revolution, approximately 1910-1920.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers