Library of Congress's Blog, page 123

November 7, 2016

New Online: Website Updates, Education Resources & New Collections

(The following is a guest post by William Kellum, manager in the Library’s Web Services Division.)

Website Updates

The Library’s new home page was released released last week, and you can read all about it in this excellent Library of Congress blog post. The Library’s Web Services team took advantage of the home page project to improve millions of other pages on loc.gov. Under the hood, we’ve put in substantial improvements to our overall design, including better support for mobile devices, improved accessibility and an overall simplification of our visual design to make content easier to read and use. Over the next several months, we’ll be converting more sections of our site to use this new interface. For now, all of our collections and search pages have been upgraded.

Elections Resources

Just in time for the November 8th election is an upgraded and updated version of the Education Outreach team’s Elections Classroom Materials. The presentation focuses on the presidential election process, how the founders and others in the United States government determined who could vote in elections, how the right to vote has expanded and been protected and the different issues that have played a role in presidential campaigns. The presentation is illustrated with primary source materials from the Library’s collections.

Heritage Months

November is Native American Heritage Month. The Library of Congress, National Archives and Records Administration, National Endowment for the Humanities, National Gallery of Art, National Park Service, Smithsonian Institution and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum join in paying tribute to the rich ancestry and traditions of Native Americans. The site is the fourth of the six heritage portals that we maintain that has gotten a full redesign treatment this year, joining Asian Pacific Heritage Month, Jewish American Heritage Month and Hispanic Heritage Month.

New Collections

Since 1932, the National Press Club has hosted luncheon gatherings that have allowed presidents, visiting world leaders and other leading personages to address the press and answer questions about pressing current affairs. In 1969, the Press Club donated to the Library of Congress audiotapes of talks they had been recording since 1952, a collection that has grown to nearly 2,000 recordings. You can read more about the collection in this blog post. The Library has made available online talks by some of its most important luncheon speakers, including presidents, international leaders and other political and cultural icons of the period, including Muhammad Ali and Ken Norton, Leonard Bernstein, Fidel Castro, Alfred Hitchcock, Audrey Hepburn and eight U.S. presidents.

Accompanying essays set the topics discussed into relevant historical contexts and provide suggestions for further reading.

{mediaObjectId:'3BEEDECF2A3A0190E0538C93F1160190',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

In this recording from 1959, Leonard Bernstein discusses his tour of the Soviet Union, Rock Music, West Side Story, and more. Library staff has also created an excellent detailed essay on this talk that provides historical context and analysis.

Library in the News: October 2016 Edition

The month of October continued to see the arrival of Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden in the news.

Featured on the cover of Library Journal, Hayden sat down with the magazine to outline her vision for the Library.

Her underlying agenda, noted reporter Meredith Schwartz, is to “make LC the library of the American people, as well as of Congress, and to use a combination of in person events and expanded digital access to accomplish it.”

CNN joined the new Librarian during her first few days in office, where she toured the Library’s map collection, checked out digital preservation equipment and lead story time at the Young Readers Center.

“As a history major, to be part of making history was humbling, exciting and it also made me think, if I can make history, anybody can make history,” Hayden said.

Hayden also spoke with the Kojo Nnamdi Show on WAMU about the varied audiences she serves as new Librarian, technology’s role in the institution and her love of books.

Speaking of the Librarian, Hayden was on hand Oct. 10 during the Library’s semi-annual Main Reading Room open house. Not only was her participation a special treat for visitors, she also officially opened the Librarian’s Ceremonial Office in the Thomas Jefferson for regular public viewing – the first time in history. Tayla Burney from the Kojo Nnamdi Show stopped by to check out one of the most notable items in the Library’s collections – the contents of Abraham Lincoln’s pockets on the night he died – that was discovered in the ceremonial office in 1975.

The New York Times featured the ceremonial office as one of the “Seats of Power” in an Oct. 27 feature.

“I think I could write a book or two if I used an office like this,” Hayden said. “There would be more scholarly output in an office like this. It also makes you think about human creativity and artistic ability. We don’t always have that kind of beautiful, beautiful, beautiful work anymore.”

Also covering the open house was The Washington Post and Federal News Radio.

In addition, the Library’s Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Preservation hosted its first-ever open house on the same day. Local newspaper the Culpeper Star-Exponent covered the event.

“A wooden hand-held camera used to film World War I, the original camera negative for Walt Disney’s ‘Snow White,’ the only known print of the 1910 Thomas Edison Studio production of ‘Frankenstein,’ and show business materials donated by legendary comedian Jerry Lewis were among items on display,” wrote reporter Allison Brody Champion.

The Packard Campus is regularly in the news, largely for its film preservation work and the fact that the building was once a nuclear bunker during the Cold War.

“Now, it’s a one-stop shop for all things regarding film preservation and restoration, with miles of shelves stacked with film reels to the ceilings, all sorts of machines that can repair film, process film, and print film, and any sort of video player you can imagine to play any sort of format that ever existed,” wrote Casey Chan for Gizmodo.

And, for an interesting spin on the Library’s collections, how about taking a course from Carl Sagan? The Library has recently digitized materials for two of his courses, including a 1965 Planetary Science Course and a 1986 course in Critical Thinking in Science and Non-Science Context. Nerdist took a look, calling the problem sets of the “celestial godfather” “no joke.”

November 4, 2016

Pic of the Week: Diary of a Wimpy Kid

Jeff Kinney teaches a young audience member how to draw his characters. Photo by Shawn Miller.

New York Times bestselling children’s author Jeff Kinney stopped by the Library of Congress on Tuesday to launch his world tour and debut his new book, “Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Double Down.” The Library’s Coolidge Auditorium was filled with young fans from area schools eager to ask questions. This wasn’t the first time Kinney has come to the Library. He’s participated in two National Book Festivals, and you can view the videos here.

October 31, 2016

A New Home Page for loc.gov

(The following is a post by Gayle Osterberg, director of communications for the Library of Congress.)

The Library of Congress launched its first website in 1994. Since that time we have digitized and made available millions of items from our collections and added new features to help you take advantage of all that the Library offers.

During the past three years, the Library’s web team has been transitioning these vast online collections into a new format that is mobile friendly, enables faceted search across all formats — books, maps, photographs and more — and applies consistent information and presentation.

Today, we present a new home page for loc.gov that we hope will give visitors an ever-changing window into all this updated content. The new page will update frequently, reflecting the dynamic and resource-filled institution that is your nation’s library.

We are really excited about this new design because it lets us highlight more of the collections, services and programs that are available for you. It’s mobile-friendly and accessible to users with disabilities. Here is a breakdown of what you’ll find:

Top Carousel

The top of the page features topical content that you’ll want to learn about — a newly digitized or updated collection, major Library events and new resources and services. The selections here will usually change monthly.

[image error]

Trending

The “Top Searches” is a set of topics that users search for most frequently on loc.gov.

The “Featured Item” is a staff favorite from the Library’s collections, and we have a lot to choose from! We thought the Abraham Lincoln campaign banner was fitting for this U.S. presidential election season (and is one of my favorite things I’ve gotten to see at the Library).

The rest of the “Trending” section will serve as a dynamic space to expose more resources and voices from around the Library. We will feature recently published blog posts from our 16 blogs, options for connecting with Library experts, and other timely information.

[image error]

Your Library

In “Your Library” you can plan a visit, learn about the Library’s research centers and how to use them, and ask a librarian a question through our online reference service. This section also lists exhibitions currently on site, upcoming events and the latest news.

[image error]

Free to Use and Reuse

The bottom of the page will feature items from the Library’s digital collections that the Library believes are freely available for your use. The Library believes that this content is either in the public domain, a U.S. government work, has no known copyright or has been cleared by the copyright owner for public use. (Please remember that rights assessment is your responsibility). The content featured here will change regularly.

Remember, this featured content is just a small sample of the Library’s digital collections that are freely available for your use. The digital collections comprise millions of items including books, newspapers, manuscripts, prints and photos, maps, musical scores, recordings and more. Whenever possible, each collection item has its own rights statement, which should be consulted for guidance. See more information about copyright and the Library’s collections.

Also, while the Library has digitized and made these collections available (and continues to digitize more content every day), even more of our collections are only available on our Washington, D.C. campus. We have a team of experts ready to help you with your research, and you can get in touch with them through our Ask A Librarian service.

We hope to see you often – on loc.gov or here in Washington!

Page from the Past: War of the Worlds

(The following was written by Audrey Fischer for the July/August 2016 Library of Congress Magazine, LCM.)

[image error]

Orson Welles.

The story is legendary in the annals of broadcasting history.

On the evening of Sunday, Oct. 30, 1938, a young Orson Welles directed and narrated a radio adaption of H.G. Wells’ novel, “The War of the Worlds” for his radio series “The Mercury Theatre on the Air.”

Published in 1898, Wells’ science-fiction work depicts an alien invasion of southern England by Martians. The radio dramatization told a similar tale in a series of news bulletins and eyewitness accounts that added to the story’s realism. Despite repeated warnings about the fictional nature of the broadcast, some listeners believed that a small town in New Jersey was in the midst of an alien invasion. The legend goes that the misunderstanding led to mass panic.

But just how many people were listening? “The Mercury Theatre” series, which aired over the Columbia Broadcasting System, had recently moved from Mondays to the Sunday night time slot and faced stiff competition from NBC’s Chase and Sanborn Hour featuring ventriloquist Edgar Bergen (and his dummy Charlie McCarthy). A telephone survey of 5,000 households conducted that evening showed that only about 2 percent had tuned into the dramatic reading of “The War of the Worlds” and most were aware that it was fictitious.

Nonetheless, the newspapers had a field day with headlines like the one pictured here from the Oct. 31, 1938, edition of the San Francisco Chronicle. These sensationalized stories popularized the acceptance in the years that followed the 1938 broadcast that a widespread panic had occured. Some media analysts have theorized that the newspaper industry sought to discredit the new kids on the block—radio— as a medium not to be trusted to provide truth to the masses.

October 28, 2016

Food for Thought: Presidents, Premiers at Press Club Luncheons

(The following is a story written by Mark Hartsell for the Gazette, the Library of Congress staff newsletter.)

[image error]

Fidel Castro

For decades at the National Press Club, America got acquainted with the men and women who made history: presidents and premiers, rising stars and old heroes, allies and enemies, establishment figures and revolutionaries – all hoping to explain themselves, over lunch, to the public.

“I am not afraid of any questions for one reason: I believe in what I do. I tell what I think, and I do what I tell,” Fidel Castro told journalists at the club in 1959, just three months after he helped over- throw the Cuban government.

Since 1932, the National Press Club has hosted luncheons that offer prominent figures the chance to meet the Washington journalism establishment and, perhaps, like the young rebel Castro, make news. Those gatherings served as a forum for many of the 20th century’s most important leaders: Truman, Eisenhower, Khrushchev, Reagan, Thatcher, Nixon, Begin, Sadat and de Gaulle.

The club donated nearly 2,000 recordings of the luncheons to the Library of Congress in 1969. Last week, the Library launched a web presentation that showcases more than two dozen of the recordings – many of them speeches that haven’t been heard in their entirety since they were delivered decades ago.

The presentation, “Food for Thought: Presidents, Prime Ministers, and other National Press Club Luncheon Speakers, 1954–1989,” is now available online.

“In recognition of the historical importance of the luncheon talks, the Library of Congress has undertaken to digitize the complete National Press Club collection of recordings,” said Eugene DeAnna, head of the Library’s Recorded Sound Section. “Researchers visiting our Recorded Sound Research Center can listen to any of the hundreds of speeches, but we have selected talks by some of the most distinguished speakers.

“This enlightening online presentation has great potential for use in the classroom because audio has the ability to convey experience and ideas more powerfully than the written word.”

The speeches capture history as told by the people who made it.

In 1958, then-Vice President Richard Nixon spoke at the club following a “good-will” trip to South America that ended in violent anti-American demonstrations. March on Washington director A. Philip Randolph addressed the club in 1963, two days before the historic civil-rights demonstration.

Ronald Reagan, a movie star turned rising political star, spoke at the club just after his dominating victory in the California gubernatorial election of 1966.

[image error]

Ronald Reagan

Reagan discussed his philosophy of governance, the Civil Rights Act, the Watts riots and the Supreme Court’s ruling in Miranda v. Arizona – and poked some fun at his old movies and the career he’d left behind.

“You just sit up late enough at night in front of the TV set and they all come back to haunt us. Sometimes as I sit there, I think it’s like looking at a son you never knew you had,” Reagan quipped.

Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev appeared at the club the day after his arrival in Washington in 1959 on the first visit by a Soviet leader to the United States.

In a nationally televised address, Khrushchev gave Americans their rst close-up view of the man who recently had promised the U.S., “We will bury you.” In a combative question-and-answer session with the press, Khrushchev tried to explain himself.

“Now, capitalism is fighting against communism. I personally am convinced that communism would be victorious,” he said. “As a system of society which provides better possibilities for the development of a country’s productive forces, which enables every person to develop his capacities best and ensures full freedom of a person in that society. Many of you will not agree with that.

“What is to be done? Let us each of us live under the system which we prefer.” Sixteen years later, the woman who helped the West win that struggle with the Soviets made her Washington debut in the same forum.

“In the past generation, there are many political giants: Marshall, Bevin, Churchill, Adenauer, de Gaulle, Roosevelt, Truman, Eisenhower – all in their different ways met the challenge of their times,” Margaret Thatcher told the Press Club crowd. “Today, we have to meet the challenge of our times.”

She did. Thatcher went on to become the first woman prime minister in British history and, along with Reagan, played a key role in achieving the West’s Cold War victory.

The luncheons weren’t all war, life and death; there were fun and games, too.

Muhammad Ali spars with Ken Norton at the Press Club in 1976.

Heavyweight champ Muhammad Ali sparred with rival Ken Norton at the club in 1976 before the third and last of their three great bouts. Comedian Bob Hope needled accident-prone pal and ex-President Gerald Ford about his golf game: “He made golf a contact sport. You never have to worry about his score – you just look back along the fairway and count the wounded.”

Director Alfred Hitchcock, in town to promote his new thriller “The Birds,” delivered 20 minutes of deadpan one-liners, then took questions. Who, he was asked, is your favorite actor?

“There is no such thing. Actors and actresses are necessary evils that we have to tolerate in our business,” Hitchcock joked. “I’ve always said, apropos of this problem of actors and actresses, that Mr. Disney has the right idea.”

Collectively, the luncheon talks provide an audio window into the past that help reveal how movers and shapers of the Cold War era explained divergent policies, opinions and worldviews, said presentation curator Alan Gevinson of the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division.

“We hear not just their words, but also attitudes, expressiveness and personal charm,” Gevinson said. “Our views of the past always inform our understandings of the present, and listening to these talks can aid in clarifying the issues, events, and conflicts of a bygone era that still impact us today.

All photos courtesy of the National Press Club archives.

October 26, 2016

World War 1: “Kim,” the Life Saver

(The following is a guest blog post by Mark Diminution, chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, and Elizabeth Gettins, Library of Congress digital library specialist.)

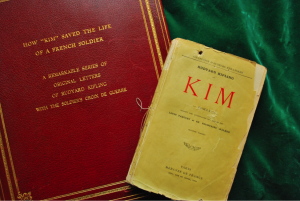

“Kim,” by Rudyard Kipling, with bullet hole on upper left corner. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

There are the occasional stories that one hears about a book saving a life due to an informational or even spiritual message, but how many people can claim a book literally saved their life? Maurice Hamonneau did.

Hamonneau, a French legionnaire and the last survivor of an artillery attack near Verdun in the First World War, lay wounded and unconscious for hours after the battle. When he regained his senses, he found that a copy of the 1913 French pocket edition of “Kim,” by Rudyard Kipling, had deflected a bullet and saved his life by a mere 20 pages. Hamonneau’s reward was a Croix de Guerre medal, which also engendered a close friendship with the noted author. Hearing that Kipling was mourning the loss of his son John, who had served with the Irish Guards, the young Frenchman was moved to send the medal and the torn copy of “Kim” to Kipling. Kipling was overwhelmed and insisted that he would return the book and medal if Hamonneau were ever to have a son. Hannonneau did and named him Jean in honor of John Kipling. Kipling returned the items with a charming letter to young Jean, advising him to always carry a book of at least 350 pages in the left breast pocket.

Hamonneau’s Croix de Guerre medal. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

The book is now in the collections of the Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division. The work was a gift from Armida Maria-Theresa and Harris Dunscombe Colt and joins a sizable collection of Kiplingiana, including a large number of early editions, manuscripts, photograph, realia and a great deal of supporting secondary materials that chronicle Kipling’s life and works.

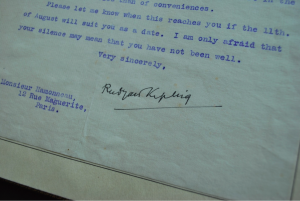

Letter exchanged between Kipling and Hammoneau. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

In addition to the book, the Library has the original Kipling/Hammoneau correspondence dating from December 1918 through September 1933. There are eight handwritten and six typescript letters in total.

Mark Dimunation, chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, talks about Kipling’s life-saving book in this video.

{mediaObjectId:'E70D96A4F87F0174E0438C93F0280174',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

*All photographs by Emily Grover

World War I Centennial, 2017-2018: With the most comprehensive collection of multi-format World War I holdings in the nation, the Library of Congress is a unique resource for primary source materials, education plans, public programs and on-site visitor experiences about The Great War including exhibits, symposia and book talks.

October 24, 2016

A New Look at America’s Insurgents and the King They Left Behind

From left: Oliver Urquhart Irvine, Librarian, Royal Library and Royal Archives; Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden; and Dr. Joanna Newman, Vice President and Vice Principal (International) King’s College London sign MOU. Photo by David Rice

King George III of England: wasn’t he the one effectively told by the feisty New World colonists to “Nix the tax, Rex?” When they turned Boston Harbor into the world’s largest teapot, it was to get the attention of a government back home in England headed by George III, a monarch they would eventually disown.

But a new collaboration between the United Kingdom institutions holding George’s papers and the Library of Congress, which preserves the papers of many of the United States’ seminal figures, may shed new light on this admittedly thorny relationship.

The Library of Congress holds the papers of many Founding Fathers (and Founding Mothers – women were well-represented in the early history of this nation, and left a record we can learn from today). Meanwhile, the letters, official edicts and other historical records of King George III reside in the United Kingdom, under the jurisdiction of the Royal Library and Royal Archives.

Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden today signed a memorandum of understanding with the Royal Library and King’s College London. The pact will provide personnel from the Library of Congress Digital Stewardship Residency program to aid in creating digital background information (“metadata”) for the papers of George III; it will also lay the groundwork for a special joint academic conference and a possible exhibition at the Library of Congress in 2020/2021, featuring materials of George III and such American figures as President George Washington.

The project is just one example of how the Library of Congress, under new Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden, is reaching out both nationally and internationally to forge new alliances. The goal of all this outreach is to make useful linkages and place assets online with all due speed.

Considering what we know about George Washington’s determination not to become, as leader of the new nation, a king by any other name, this promises to be a very interesting collaboration.

October 21, 2016

Pics of the Week: Opening the Door

Barbara Morland, head of the Main Reading Room, speaks with visitors.

Last Monday, the Library of Congress welcomed thousands of visitors into its Main Reading Room for the twice-yearly open house. New this year was an open house a few miles down the road at the Library’s Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Preservation, where the free tour tickets quickly “sold out” on Eventbrite in advance of the event.

[image error]

Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden shows visitors the Ceremonial Office.

While opening the doors to the Main Reading Room was certainly a treat, the open house packed a double whammy for visitors. Not only was Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden on hand to meet attendees, she also announced that the Ceremonial Office of the Jefferson Building will be open for regular viewing by the public – the first time in the building’s 119-year history the room will regularly be open to visitors. Those at the open house were the first to enjoy the opportunity.

[image error]

Lesli Foster of WUSA9 looks over the contents of President Abraham Lincoln’s pockets on the night he was assassinated, October 10, 2016. Photo by Shawn Miller.

“I thought it would be wonderful to let everyone have a chance every day, whenever the Library is open, to come into the librarian’s office and feel the wonder of this jewel box,” Hayden said.

All photos by Shawn Miller

October 20, 2016

Rare Book of the Month: “The Raven” and Mr. Halloween Himself

(The following is a guest blog post written by Elizabeth Gettins, Library of Congress digital library specialist.)

[image error]

The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe; Illustrated By Gustave Doré; With comment By Edmund C. Stedman. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1884. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Halloween is upon us and what better time to recount some of the classic gothic stories by American writers? Henry James’ ghostly tale “The Turn of the Screw” (1898) and Washington Irving’s headless horseman from “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” (1820) may readily come to mind. Some may even think of H.P. Lovecraft’s “Shadow over Innsmouth” (1931). However, it stands to reason that many would think of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” as a quintessential American gothic tale.

Poe published the poem in January 1845, and it became an overnight success. It still remains one of the most famous poems ever written. Poe became a household name almost immediately and is widely known as a founding father of Romanticism in American literature. He can also boast being one of the first American writers to work with the short story genre, helping to invent detective fiction, as well as creating the genre of science fiction.

There are many publications of “The Raven” that include artwork by well-known illustrators, including the likes of John Tenniel and Édouard Manet. Here we feature an edition of “The Raven” with illustrations by the French national Gustave Doré (1832-1883). You can view the edition in several ways, including a handy page-turner or simple pdf.

Known as an oversized edition, it measuring 47 centimeters and features 28 finely detailed woodcuts depicting the scenes from the poem. Paging through the digital copy, one can see the poem come alive with haunting portrayals of the scenes that Poe describes. The tome was published in 1884 by Harper & Brothers, shortly after the Doré’s death. Doré was a child prodigy and began carving in cement by the age of seven. At the age of 15 he began his career of printmaking for books for famous authors including Rabelais, Balzac, Milton and Dante and Byron. Doré was self-taught and his art quite prolific. His engravings are considered to be some of the finest examples ever made.

displays.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers