Library of Congress's Blog, page 124

October 18, 2016

Very Superstitious

The Black Cat, October, 1895. Prints and Photographs Division.

To say I’m not very superstitious is like saying the sky isn’t blue. I can probably attribute it (very lovingly) to my mother. I can recall on a few occasions being halfway down the road when a black cat crossed in front of our car and my mom immediately turned around to go back the way we came, only to turn back around to continue on in the right direction. The backtracking apparently negated the bad luck. Don’t even get me started with knocking on wood – a habit that I can’t quite break even today. And, if my mom is reading this, perhaps she can clarify who comes to visit when you drop a spoon, fork or knife – I can never remember!

Certainly every culture, community and even family has superstitions ranging from the mundane to just plain silly. The Library’s collections are full of accounts of local lore, many from its various oral history collections like “American Life Histories” from the Federal Writers’ Project. Following are just a sample. Search for “superstitions” in the collection for many more.

In this narrative from the Federal Writers’ Project collection, “Myer” recounted Yiddish folklore from his grandfather, who would admonish him not to whistle lest all the evil spirits be called together.

Mrs. Erret Hicks believed in several superstitions: If a dog howls under your window, it is a sure sign of death for someone you love. The breakage of anything you like or admire is a sign that you are losing a friend or sweetheart. Always put your right shoe on first or bad luck will follow. If a child is born with a caul over his face, he will never suffer a death of drowning and will be a genius.

Mrs. Ernest P. Truesdell recalled a few “uninteresting” superstitions including returning to your house after you just left meant bad luck. To offset the bad luck, you needed to go sit on your bed for a few minutes.

An old Russian superstition, as told by Gussie Spector, believes that if you see leaves turning around in the wind, the devil is there.

This post was actually inspired by a story on Slate’s The Vault blog on lost superstitions. The post highlighted the work of Fletcher Bascom Dressler, who wrote a book on a research study he conducted on superstition and education at the University of California. The Library has a copy in its collections. The list of superstitions is quite thorough. Some of the most common include dropping a dishrag means company is coming, never begin a new task on Friday because it will mean bad luck, dreaming of snakes means you have an enemy and opening an umbrella inside means bad luck.

Believing in superstitions may be a habit that is comforting without the consequences. Goodness knows, I’ve broken a mirror and not suffered bad luck. And I’ve certainly walked by my fair share of black cats. Still, I find I come back to them now and again. Perhaps Carl Sagan said it best in this note from Sept. 21, 1979:

“Superstitions may be comforting for a while. But, because they avoid rather than confront the world, they are doomed. The future belongs to those able to learn, to chance, to accommodate to this exquisite Cosmos that we have been privileged to inhabit for a brief moment.”

October 14, 2016

King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand (1927-2016)

The following cross-post is written by Cait Miller and originally appeared on the In the Muse blog.

The following post is co-written with Musical Instruments Curator Carol Lynn Ward-Bamford.

[image error]

His Majesty, King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand, visited the Library of Congress on June 29,1960 as part of his official visit in the Nationa’s Capital. Pictured viewing the Thai musical instruments, which were a gift of His Majesty’s to the Library, are left to right: Harold Spivacke, Chief of the Library’s Music Division, His Majesty, Cecil Hobbs, Head of the South Asia Section, Library of Congress, and Librarian of Congress L. Quincy Mumford.

Early yesterday morning the world learned of the death of Thailand’s King Bhumibol Adulyadej, crowned in 1946 and known as the world’s longest-reigning monarch. Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts and educated in Switzerland and the United States, King Bhumibol was interested in musical performance and composition, and played clarinet and other reed instruments. In 1960, His Majesty visited the Library of Congress as part of an official visit to the United States. While visiting, the King presented the Library with ten musical instruments, including a pair of ching (hand cymbals), one thon and one rammanā (small hand-played drums), two khlui ū (bamboo flutes, small and medium), one jakhē (čhakhē, a three-string zither), and two sq duang and two sq ū, both being forms of a vertically played two-string fiddle. A silver plaque accompanying the gift carried these engraved words: To the Library of Congress. This set of Thai musical instruments is presented as a token of sincere respect for a centre of knowledge and culture. Washington, DC, 1960.Further enriching King Bhumibol’s generous gift made over half a century ago, the Music Division is also home to the Bhumibol Adulyadej (King of Thailand) Collection, consisting of his compositions (13 music manuscripts and 100 pieces of printed music), clippings, correspondence, and other miscellaneous documents. The collection had been assembled by Serge Rips, a friend of the King of Thailand. His Majesty’s original compositions are closely tied to traditional Thai musical influences; however, they simultaneously reflect his affinity for jazz and swing music. Specific jazz influences include Benny Goodman, Jack Teagarden, and Lionel Hampton, with whom he participated in jam sessions.

October 12, 2016

World War 1: Irving Greenwald’s WWI Diary

(The following is a guest post by VHP Reference Specialist Megan Harris, reprinted from the Folklife Today blog.)

[image error]One look at Irving Greenwald’s diary is all it takes to bring to mind the old adage “good things come in small packages.” This World War I diary, written by Pfc. Irving Greenwald, was donated to the Veterans History Project (VHP) in December 2015 by his family.

The diary itself is small – pocket-sized, only slightly larger than a pack of cigarettes. When Greenwald’s grandson brought it by the VHP offices last December and opened it up to show us the contents, I gasped: the diary is written in the tiniest, most-minute handwriting I have ever seen. It starts off small, and then gets even smaller and then smaller still. It is unfathomable how Greenwald was able to write such teeny print – particularly in light of the fact that much of the diary was written while he was serving in combat in France, and then after he was injured and recuperating in the hospital.

Some portions of the diary can be read by the naked eye, but much of it is so small and blurred with age as to render it illegible. Luckily, the diary was transcribed by Greenwald’s daughter and sister in the late 1930s. Reading through the diary transcript, I got goosebumps all over again. Greenwald wrote in a staccato, rat-a-tat manner, focusing on specific elements of his daily routine. At first glance, his prose seems mostly fact-based, without a lot of extraneous emotional content. Reading further, I realized that not only are his entries jam-packed with rich historical details, but they also contain deeply poignant passages that convey the enormity of his experiences in a few concise sentences. Here’s an early entry that caught my eye; in it, Greenwald describes receiving a pass that will allow him time away from training at Camp Upton so that he may visit his wife:[image error]

December 23, 1917: Up at 6:45. Roll call. Breakfast, orange, pettijohn’s, hash, coffee. Made bed. Tidied bunk. Then began great preparations for journey home. Shined shoes, dressed, packed grip, shaved with infinite care. 9:30 and get my pass. I walked on air.

Greenwald’s diary also connects to one of the most famous American units of World War I, as he was part of the “Lost Battalion,” a group known for the losses they incurred during battle in the Argonne Forest in October 1918. Part of the 77th Division, the nine companies that were part of the Lost Battalion were cut off from the rest of the Allied forces and spent a week in a ravine surrounded by the Germans. Of the more than 500 soldiers in the group, only 194 survived; the rest were killed, missing in action or were taken prisoner. Following their rescue, the Lost Battalion immediately became notable for the circumstances of the battle, and the story has become part of WWI lore. For example, carrier pigeons were used by stranded members of the unit to communicate with headquarters; one of these carrier pigeons, Cher Ami, was eventually preserved and is on display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

You can watch more about Greenwald’s diary in this video.

{mediaObjectId:'3EB02EDB001900F4E0538C93F11600F4',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

WWI Video Transcript

Do you have original WWI material that you would like to see preserved at the Library of Congress? Please consider donating it to the Veterans History Project!

World War I Centennial, 2017-2018: With the most comprehensive collection of multi-format World War I holdings in the nation, the Library of Congress is a unique resource for primary source materials, education plans, public programs and on-site visitor experiences about The Great War including exhibits, symposia and book talks.

October 11, 2016

Technology at the Library: Display By Design

(The following is an article in the September/October 2016 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. The article was written by Fenella France, chief of the Library’s Preservation, Research and Testing Division.)

Physicist Charles Tilford attaches an apparatus that replaces air in the encasement with inert argon gas to help preserve the 1507 Waldemüller map. Photo courtesy of the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Technological advancements have made it possible for the Library to put several rare maps on long-term display.

Preserving and making the Library’s vast collection accessible to researchers is a challenge. Even more challenging is putting rare and unique items on display. Lighting, temperature and even air itself pose a threat.

The Library, in collaboration with National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), has designed, constructed and installed anoxic (oxygen-free), hermetically sealed encasements to mitigate the potentially damaging effects of long-term display.

Oxygen promotes the deterioration of materials such as paper, parchment, and organic-based media including inks and other colorants. This deterioration is often visible as yellowing, embrittlement and color-fading.

Anoxic encasements are created by displacing oxygen with an inert gas, such as nitrogen or argon. A good seal that can maintain interior case conditions requires advanced case construction, materials and design.

In addition to allowing oxygen-free display, the encasements have to meet preservation needs for long-term display of historic materials; allow monitoring of the maps by measuring environmental changes; integrate with the Library’s electronic and security infrastructure monitoring and be movable.

The Library first began using the special encasement in 2007 to display Martin Waldseemüller’s 1507 world map— the earliest known map to name the land mass of “America.”

A crane hoists a specially designed map encasement into the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building. Photo by Dianne van der Reyden.

More recently, the Library worked with NIST in 2013 to design, construct and install another anoxic encasement to display Abel Buell’s 1784 map— the first map of the newly independent United States that was compiled, printed and published in America by an American.

One challenge in the design of the Buell map encasement was to replace an oxygen sensor used for the previous encasement monitoring that was no longer commercially available. A prototype of the sensor was built, calibrated and tested, and is currently in use for the monitoring of the interior conditions of the Buell case.

The encasement, tooled from a single block of aluminum and covered with hurricane- proof glass, allows tight control of the map’s environment, reducing its potential degradation by oxygen and moisture. Performance testing of cases and sensors is an ongoing program in the Library’s Preservation Research and Testing Division.

You can read the complete issue of the September/October 2016 LCM here.

October 7, 2016

New Website on Martin Waldseemüller

The Geography and Map Division of the Library of Congress and the Galileo Museum in Florence, Italy, today unveiled a multi-media interactive website that celebrates the life and times of 16th-century cartographer Martin Waldseemüller, who created the 1507 World Map, which is the first document to use the name “America,” represent the Pacific Ocean and depict a separate and full Western Hemisphere.

[image error]

1507 Waldseemüller map. Geography and Map Division.

The website, “A Land Beyond the Stars,” brings the map’s wealth of historical, technical, scientific and geographic data to a broader public. Interactive videos explain the sciences of cartography and astronomy and the state of navigational and geographic knowledge during the time of Waldseemüller. Developed with materials from the Library of Congress and other libraries around the world, the name of the website stems from Waldseemüller’s use of a passage from Roman poet Virgil, which can be found in the upper left corner of the 1507 map.

The 1507 map is the crown jewel of the unparalleled collections of maps and atlases in the Geography and Map Division at the Library of Congress. It is the only known surviving copy of the first printed edition of the map, which, some scholars believe, consisted of 1,000 copies. In 2003, the Library purchased Waldseemüller’s 1507 map from Prince Waldburg-Wolfegg in Baden-Württenberg, Germany, whose family owned it—and Waldseemüller’s 1516 Carta Marina, a nautical map of the entire world—for many centuries. Jay I. Kislak, a member of the Library’s James Madison Council, a private-sector advisory group, purchased the Carta Marina and donated it to the Library in 2014.

In 1507, cartographers in St. Dié, near Strasbourg, France, undertook an ambitious project to document and update new geographic knowledge derived from the discoveries of the late 15th and the first years of the 16th centuries. Waldseemüller’s world map was the most exciting product of that effort and included data gathered during Amerigo Vespucci’s voyages of 1501–1502 to the New World. Waldseemüller christened the new lands “America” in recognition of Vespucci’s understanding that a new continent had been uncovered, as a result of the voyages of Columbus and other explorers in the late 15th century.

The Galileo Museum, in collaboration with the Library of Congress, created the online multimedia presentation. Ente Cassa di Risparmio, a foundation in Florence, sponsored the project.

October 6, 2016

Mapping the Imaginary

(The following is an article written by Hannah Stahl and featured in the September/October 2016 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. Stahl is a library technician in the Library’s Geography and Map Division. This article is adapted from a series of posts by the author on the Geography and Map Division’s blog.)

Maps of fictional places in life and literature help fuel our imaginations.

[image error]

1973 facsimile by Daniel Devereaux of “Royaume d’Amour” (Kingdom of Love), created by Tristan l’Hermite and Jean Sadeler in 1650. Geography and Map Division.

Among the road maps, topographic maps and country maps in the Library’s Geography and Map Division are maps of intangible places that will set the hearts of ction and fantasy lovers aflutter.

The practice of mapping imaginary worlds started as early as the Middle Ages and continued to be popular during the Renaissance. Readers of Dante’s “Inferno,” written in the 14th century, have mapped the nine circles of Hell through which Dante traveled. Another 14th-century work, Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales,” has inspired maps showing the pilgrimage from London to Canterbury.

Some of the most famous maps of imaginary places created during the Renaissance also depict imaginary journeys. One such map is the “Royaume d’Amour/Kingdom of Love,” created by Tristan l’Hermite and Jean Sadeler, and published in 1650. This map, which shows the journey of love, depicts the real island of Kythira (Cythera) in Greece. The mythical Aphrodite, goddess of love, was said to have lived there, making the island a perfect place for the Royaume d’Amour. It includes fictional place names such as “Grande Plaine d’Indifference” (the Great Plain of Indifference)—places that lovers who travel in the Royaume d’Amour would eventually reach on their journey.

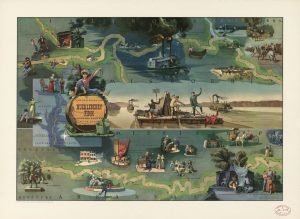

Many fictional stories take place in the real world, as in Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice” (1813), which inspired one reader to create “ ” to show important places in her novels. Similarly, readers have depicted Huckleberry Finn’s journey down the Mississippi River as told by Mark Twain.

Based on the novel by Mark Twain, this

pictorial map by Everett Henry shows Huckleberry Finn’s adventures on the Mississippi River. Cleveland, Ohio: Harris-Intertype Corp., 1959. Geography and Map Division

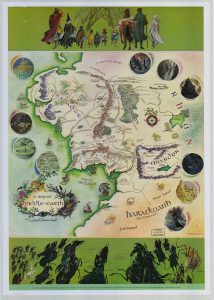

Authors who include maps of imaginary worlds in their works help their readers disappear from their comfy armchairs by the fire into fictional worlds, perhaps with dragons and magic. Where would we be if A. A. Milne had not shown us the Hundred Acre Wood inhabited by Winnie-the-Pooh and his friends or if J. R. R. Tolkien had not plotted Frodo’s journey to Mordor? The first edition of Tolkien’s “The Lord of the Rings” (1954) actually contained three maps: a general map of Middle-earth, a map of the Shire and a detailed map showing Rohan, Gondor and Mordor. Would we lose elements of the story if these maps did not exist?

The mapping of imaginary worlds is as popular as ever today. The Geography and Map Division holds a collection of maps showing places in George R. R. Martin’s “A Song of Ice and Fire,” a series of books that are the basis for the popular television show, “Game of Thrones.” The beautifully illustrated maps depict in detail such places as Westeros, Essos and King’s Landing. In an interview at the Edinburgh International Book Festival in August 2014, Martin discussed the influence that Tolkien had had on his work:

“A map of Middle- Earth,” Pauline Baynes, based on the cartography of J.R.R. and C.J.R. Tolkien, London, George Allen & Unwin, 1970. Reproduced with permission from HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

“I revere ‘Lord of the Rings.’ I reread it every few years; it had an enormous effect on me as a kid. In some sense, when I started this saga I was replying to Tolkien, but even more to his modern imitators … I wanted to combine the wonder and image of Tolkien fantasy with the gloom of historical fiction.”

While Martin’s story and themes in “A Song of Ice and Fire” are different from Tolkien’s in “The Lord of the Rings,” the worlds they created consist of similar topography and both depict the journeys of the characters that inhabit them. A careful reader may see a vaguely similar style in Tolkien’s map of Middle-earth and Martin’s map of the North (North Westeros).

But why collect maps of places that exist only on the pages of books and can come to life in our imaginations? As Professor Albus Dumbledore says in J. K. Rowling’s “Harry Potter” series—which itself has inspired many maps— “Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on earth should that mean that it is not real?”

You can read the entire September/October 2016 issue of the LCM here.

October 5, 2016

Library in the News: September 2016 Edition

In case you missed it, the Library of Congress has a new Librarian of Congress, who made headlines throughout the month of September.

In addition to being named Fox News Sunday Power Play of the Week, Carla Hayden spoke with several outlets, including USA Today, The Washington Post, The Guardian, NBC, NPR, CBS, The New Yorker and C-Span.

“Being the first female and the first African American means that the legacy of the 14 Librarians of Congress will include diversity–and also a female in a female-dominated profession,” Hayden told Sarah Begley of Time Magazine.

“To be the head of an institution that’s associated with knowledge and reading and scholarship when slaves were forbidden to learn how to read on punishment of losing limbs, that’s kind of something,’’ she said during her interview with The New York Times.

“It’s a librarian’s dream,” she told Jeffrey Brown of PBS NewsHour regarding taking on the position. “And in the field, it’s seen as a job that really epitomizes what libraries can mean and symbolize. So, this library can really help libraries throughout the country show the worth of a library and a community.”

Covering Hayden’s swearing-in on Sept. 14 was Library Journal.

“The prevailing sentiment of the day was one of confidence in Hayden’s leadership and great hopes for LC’s future,” wrote Lisa Peet.

Speaking of firsts, the Library’s 16th annual National Book Festival featured a few of them, including being streamed live on Facebook. Highlights of the all-day event popped up in several news outlets.

“To walk around a major book festival and see the celebration of authors was to see that we continue to embrace the physical book over the intangible experience of a Kindle or iPad,” wrote Heather Hunter for Popzette.

“Given all the depressing statistics about children’s reading habits and screen-time addictions, the Walter E. Washington Convention Center on Saturday served as a loud-and-proud rebuttal. The place was jam-packed with children and teenagers at the annual National Book Festival, sponsored by the Library of Congress,” wrote Ian Shapira for The Washington Post.

Publishers Weekly and The Georgetowner highlighted the festival in photos.

As part of the lead-up to the festival, the Library also announced the winners of the Library of Congress Literacy Awards.

“As Frederick Douglass said, ‘Once you learn to read, you will be forever free,’” Hayden said in announcing the awards. “You will be free to explore, dream and make your own history. It is wonderful to recognize these organizations that are doing so much to fulfill that promise for countless lives, from remote aboriginal communities in Australia to as close as our own back yard of Washington, D.C.” The Washington Post covered the program honoring the recipients.

In other news, the Library has completed a three-year project, financed by Carnegie Corporation of New York, to digitize holdings of the Library of Congress relating to the culture and history of Afghanistan, for use by that nation’s cultural and educational institutions.

“The next generation of Afghans will have a whole lot more than that at their fingertips, thanks in part to a major initiative from the U.S. Library of Congress,” wrote Teresa Welsh for McClatchy. “Much of the material in the Library of Congress’ archive can’t be found in Afghanistan itself and some unique documents can’t be found anywhere else in the world.

October 4, 2016

New Online: Today in History, Hispanic Heritage & Folklife Collections

(The following is a guest post by William Kellum, manager in the Library’s Web Services Division.)

Website Updates

Each Today in History story is accompanied by illustrative items from the Library’s collection.

Today in History is an online presentation of historic events illustrated by items from the Library’s digital collections. First established in 1997, the site was migrated this month from the American Memory site to a new home on loc.gov. The revised site features larger images, responsive design and, most importantly, hundreds of updates, corrections and enhancements. The site’s content is written by reference experts from across many of the Library’s divisions and is a great resource for teachers, history enthusiasts and more. Each illustrated story ends with suggestions for further inquiry and investigation within the Library’s rich online resources.

September brought another release of Congress.gov, featuring several enhancements and improvements – read all about them on the Law Library’s excellent blog post.

Heritage Months

National Hispanic Heritage Month is September 15 to October 15. The Library of Congress, National Archives and Records Administration, National Endowment for the Humanities, National Gallery of Art, National Park Service, Smithsonian Institution and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum join in paying tribute to the generations of Hispanic Americans who have influenced and enriched our nation and society. The Hispanic Heritage website has been redesigned and upgraded, featuring new content for 2016, a new adaptive visual design, new and improved video player and more.

Folklife Collections

The Montana Folklife Survey Collection was established in the summer of 1979 by the American Folklife Center of the Library of Congress, in cooperation with the Montana Arts Council. The survey was a field research project to document traditional folklife in Montana and joins the Chicago Ethnic Arts collection, which was released earlier this year. The collection features sound recordings, photographs and manuscripts that document interviews with Montanans in various occupations including ranching, sheep herding, blacksmithing, stone cutting, saddle making and mining. The sound recordings also feature various folk and traditional music occasions, including fiddle and mandolin music in Forsyth; fiddle and accordion music performed in Broadus; the Montana Old-Time Fiddlers Association in Polson; Irish music, songs and dance music on concertina and accordion in Butte; a Serbian wedding and reception in Butte; hymn singing of the Turner Colony of Hutterites; the annual Crow Fair in Crow Agency; storytelling on the Milk River Wagon Train; and other documentation of rodeos, trade crafts, vernacular architecture, quilting and reminiscences and stories about life in Montana in 1979. A finding aid to the entire collection is also available online.

{mediaObjectId:'38B546BB0C01003CE0538C93F116003C',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

The Montana Folklife Collection includes field recordings like this 1979 recording of Evening Dances from the Native American Crow Fair.

Online Exhibits

Finally, in conjunction with new items on display in the Library’s Jefferson Building, the online “Mapping a Growing Nation: From Independence to Statehood” exhibit features early American maps, which will eventually include maps from all 50 states. A highlight is Abel Buell’s New and Correct Map of the United States of North America, the first map of the newly independent U.S. compiled, printed and published in America by an American.

September 30, 2016

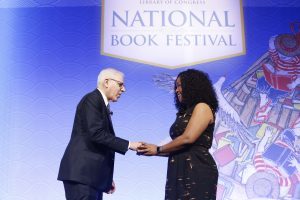

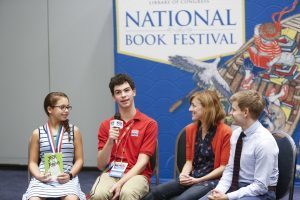

Pics of the Week: National Book Festival

The Library of Congress hosted the 16th annual National Book Festival last Saturday at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in D.C. Thousands of book-lovers came to get books signed, check out exhibits, play with their kids and get close to some of the world’s most popular authors. This year was a year of several firsts. Not only did new Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden attend as her first official event, bestowing honors on authors Stephen King and Marilynne Robinson, among other activities, but this year’s festival marked the first time a presentation was staged in the convention center’s 2,500-seat auditorium, the biggest venue in event history. And, for the first time, a festival event was streamed live on Facebook, to some 200,000 viewers.

In the coming weeks, the Library will be posting videos from the festival presentations. In the meantime, here is a sampling of photos from the event to enjoy.

[image error]

September 29, 2016

Making of the Modern Map

(The following is a feature story in the September/October 2016 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. The story is written by Ralph Ehrenburg, chief of the Library’s Geography and Map Division. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

[image error]

This 1977 manuscript painting by Heinrich C. Berann is based on the “World Ocean Floor” map by Bruce Heezen and Marie Tharp, 1977. Geography and Map Division.

Advances in technology continue to transform the ancient art and science of mapmaking.

In today’s interconnected world of communications and social networking, maps are more relevant and important than ever. Whether searching for the closest convenience store, navigating a mountain trail or planning a foreign adventure, up-to-date, detailed interactive maps of every place on the Earth are immediately available through mobile devices. Over a billion maps, for example, are viewed monthly through Google and Apple Maps’ apps and platforms. Web use is even higher, with some 3.2 billion people online—one-half of the world’s population. And many of those users are seeking geographic information at their fingertips.

But how did the practice of mapmaking evolve, from the Middle Ages to our modern day?

Human beings have always sought to make sense of the world around them. Throughout history, advances in mapmaking have been closely associated with new developments in scientific and technical tools. The “groma,” or surveyor’s cross—a simple line-of-sight instrument used by ancient Roman land surveyors to plot straight property lines and mark out building foundations—led to the first roadmaps of the Roman Empire.

Maj. J.N. Reynolds, a pilot in the 91st. Aero Squadron, lifts an aerial camera into his bi-plane with help from a bystander, 1917-1918. U.S. Signal Corps photo, Prints and Photographs Division.

The magnetic compass, invented in China and perfected in medieval Italy, gave rise to portolan charts and, later, accurate terrestrial maps. Coastal charts drawn on animal skin, known as portolan charts, guided the first Mediterranean mariners. Christopher Columbus, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, and Charles Lindbergh used maps to navigate by compass bearings.

The look of the modern map—with its lines of latitude and longitude—can be traced to the once-revolutionary concept of a spherical earth, introduced by early Greek scholars along with a series of new instruments for locating and predicting the positions of celestial bodies. In the second century, A.D., the Greco-Egyptian geographer and astronomer Claudius Ptolemy provided detailed instructions for mathematical mapmaking in “Geographia,” his treatise on cartography. He described the construction of map projections using latitude and longitude as the basic geographical frame of reference and the preparation of the first universal world map.

Tools such as the astrolabe and cross-staff, which measured the angles and elevation of the sun, moon and stars, date from classical antiquity. But it was not until seafarers ventured far beyond the Mediterranean Sea and the coast of Europe that new devices for measuring angles and distances between visible objects—such as octants, quadrants, sextants and later, chronometers—greatly improved map accuracy.

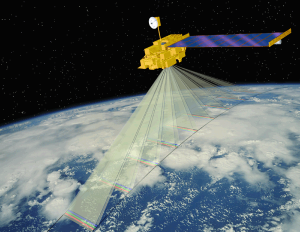

This artist concept depicts how the Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MISR) instrument aboard NASA’s Terra satellite gathers information about Earth’s atmosphere. Geography and Map Division.

Advances in technology not only had an impact on mapmaking, but on cartographic data gathering. Most dramatic was the development of aerial photography, made possible by advancements in aviation during the first few decades of the 20th century. No longer was it necessary to send large numbers of surveyors and mapmakers into the countryside to prepare basic maps. The use of aerial photography in the mapping process expanded greatly during World War I and World War II, providing the foundation for NASA’s mapping satellites, first launched in 1984.

Other instruments made it possible to acquire previously unobtainable mappable data. Data for geologists Alvara Espinosa and Wilbur Rinehart’s 1981 world map of earthquakes, for example, were obtained from seismic monitoring stations. Oceanographer Marie Tharp’s base map of the ocean floor, which confirmed the theory of plate tectonic, was derived from data obtained by echo-sounding devices developed for submarines during World War II.

Cartography has been transformed during the past half-century with the advent of computer-assisted design, followed by the development and widespread adoption of geographic information systems (GIS), global positioning systems (GPS) and satellite sensing devices.

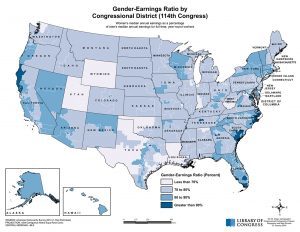

GIS is a software platform used to capture, manage, analyze, store and present layers of geospatial data that allows better understanding of geo-referenced patterns and relationships. For example, data about gender pay equity inequality in specific regions of the country can be displayed geographically.

“Gender Earnings Ratio by Congressional District (114th Congress)” | Tim St. Onge, Library of Congress Congressional Cartography Program, 2015.

GPS provides surveyors and mapmakers with precise geographic coordinates for the Earth’s surface features through a worldwide network of orbiting satellites and receiving units. It has become the primary tool for land and field surveying, and has been adopted for navigation in aircraft, boats, cars and on mobile devices. GPS technology has also made possible the popular Pokémon Go app, which tracks players’ physical locations on their smartphones and superimposes digital Pokémon characters into their real-world environments.

Satellites have increased the speed at which data can be collected and have dramatically expanded the range of mappable information. What once took months or years to survey can now be done in hours or minutes. The surface of the Earth is now mapped continuously by numerous remote-sensing satellites, producing vast archives of mappable data that are received, analyzed and maintained by cartographers, scientists, and technicians worldwide. NASA’s Terra satellite’s five environmental mapping sensors alone collect nearly 620 terabytes of data quarterly. The millions of satellite images that have been acquired and archived since the introduction of remote- sensing satellites have been used to produce millions of maps, featuring topics ranging from agriculture and forestry to the earth sciences, global change and regional planning.

The Library of Congress holds many examples of maps produced using both ancient and modern technologies. Advances in digital scanning technology have made it possible for the Library of Congress to make an increasing amount of its cartographic holdings globally accessible online.

More Information

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers