Library of Congress's Blog, page 128

July 19, 2016

Letters About Literature: Dear Caitlin Alifirenka & Martin Ganda

We continue our spotlight of letters from the Letters About Literature initiative, a national reading and writing program that asks young people in grades 4 through 12 to write to an author (living or deceased) about how his or her book affected their lives. Winners for 2016 were announced last month.

Nearly 50,000 young readers from across the country participated in this year’s initiative, which aims to instill a lifelong love of reading in the nation’s youth and to engage and nurture their passion for literature

There was a tie for the national honor award for Level 2 (grades 7-8). Following is one of the winning letters written by Hannah Huang of Iowa, who wrote to Caitlin Alifirenka and Martin Ganda, authors of “I Will Always Write Back.”

Dear Caitlin Alifirenka and Martin Ganda,

The chaos theory talks about how small fluctuations in a complicated, interconnected system, like weather, can end up causing startling consequences. It’s often illustrated by the butterfly effect – how something as insignificant as a butterfly fluttering its wings might eventually cause a hurricane in a different part of the world.

I’m no heroic butterfly – I’m a very normal girl. I go to school, do my homework, socialize with friends, and read a lot. One of the books I happened to read was your collaborative memoir – the story of two pen pals, one in a suburban Pennsylvania town, the other in the slums of Zimbabwe. “I Will Always Write Back” demonstrates the chaos theory perfectly: how small actions and choices can lead to astonishing results.

Caitlin, your chapters were like reading a page out of my own life story. Just like what I am right now, you began as an ordinary American girl. At 12 years old, when you chose to have a pen pal from Zimbabwe, you said, “I didn’t know it then – how could I have? – but that moment would change my life.”

From a simple class assignment came a friendship that bridged an ocean and changed both of your lives. But what would have happened if you hadn’t chosen Zimbabwe? What if Martin hadn’t been the top student in his class, therefore earning the honor of being your pen pal? You wouldn’t have learned about what life was like outside of a first-world Country, “…a typical twelve-year-old American girl, far more interested in what I should wear to school than what I might learn there,” is how you described yourself before your friendship with Martin. And Martin, instead of being able to attend an American university, would probably still be mired in Zimbabwe. Small choices lead to unimaginable consequences that one couldn’t have dreamed of at the time of the decision.

And that was when I had my epiphany. I used to think that my daily actions and choices had no real effect on the world at large. I mean, what could a young girl possibly do to change the world? But after reading this book, I realized that I am still able to have an impact on the small part of the world that I interact with. With this in mind, I started to volunteer my time with the preschoolers at church and my local food pantry. Teaching children a new word. Showing them how to use scissors. Giving out food that would have otherwise gone to waste. Seeing the smiles break out when I said, “Take as many tomatoes as you want.” These are small things, but I hope that they’ve affected at least a few people’s lives.

Martin, you changed Caitlin’s life, too. It might seem like Caitlin was doing all the giving and you were doing all the taking, but you gave Caitlin something valuable, too. Through your letters, you opened her eyes (and mine as well) by showing what life is like in countries that are not as lucky as America. Your family’s only furniture was a single mattress, and your “house” was a single room shared with another family. I couldn’t even imagine living in such cramped quarters. And I used to think that my own personal bedroom, equipped with a desk, bed, and a closet filled with clothes, was sparse and small.

As I continued to read, each chapter of yours increased my awareness of how naive I was. For example, I expected three fresh meals served up to me everyday day. If my mother was out and I had to make my own dinner, I would gripe about it incessantly, even with our refrigerator fully stocked and at my disposal. When I read about your family struggling even to buy sadza, the commeal mush that was your daily subsistence, I felt ashamed of myself. And while I had three pairs of boots and a different pair of sneakers allotted for running, tennis, PE, and wearing to school, I was concerned with their color, style, and brand. I realized how superficial things they were to be concerned with when I found out that you didn’t even own a single pair of shoes.

There are things in life that seem so trivial that it’s easy to forget how blessed and lucky I am to have them. I used to think of good food, a warm bed, and a roof over my head as some sort of inalienable right. I’ve since realized how mistaken I was in this notion after reading about what your life was like in Zimbabwe. It makes me all the more grateful for what I have, and when I say that I’m thankful for something at Thanksgiving, or even on a regular day, I really, truly, mean it now.

And finally, “I Will Always Write Back” taught me how to be a better friend. Both of you went above and beyond the call of duty to sustain your friendship. Caitlin, you selflessly sent your babysitting money to Martin so he could stay in school. And Martin, you were determined to continue writing to Caitlin after your school stopped financing the cost of your correspondence, even carrying luggage for travelers just to scrape together the money needed to buy the stamps to put on the envelope. You both showed me that it is worth every little bit of effort expended to keep a friendship going. Now, I strive to emulate that type of admirable loyalty in my friendships as well. Over winter break, I emailed friends that I hadn’t communicated with in years, discovering in the process that we still remembered the same treasured memories and inside jokes. And I really try my best now to look beyond the surface of an individual. The old me used to write people off if they weren’t made of the same mold I was, but now I have become friends with individuals of different ages, genders, and personalities. Your book showed me that inside every person, no matter how different compared to me, is the potential for a life-altering friendship.

Caitlin and Martin, you have taught me to open my eyes to the world around me, and ultimately, become a better person. Your unlikely friendship showed me how two people with very different nationalities, beliefs, cultures, and aspirations, can change each other’s lives. The world suddenly becomes a more vivid place when we recognize contrasts and embrace them. That is, after all, what makes color TV so much better than black and white. Both of you have helped me rethink the place I hold in this world and what results from the smallest of actions. I have much to thank you for. I daresay your friendship – a single butterfly flapping in the air – has caused a small tempest elsewhere in the hearts and minds of your readers.

Hannah Huang

You can read all the winning letters here, including the winning letters from previous years.

July 14, 2016

Letters About Literature: Dear Maya Angelou

Last month, the Library announced the 2016 winners of the Letters About Literature contest, a national reading and writing program that asks young people in grades 4 through 12 to write to an author (living or deceased) about how his or her book affected their lives.

Research shows that students benefit most from literacy instruction when they are engaged in reading and writing activities that are relevant to their daily experiences. Nearly 50,000 young readers from across the country participated in this year’s initiative, which aims to instill a lifelong love of reading in the nation’s youth and to engage and nurture their passion for literature. Nine students were given national recognition and come from all parts of the country.

We’ve already featured the winners in the Level 1 (grades 4-6) category. Today we highlight the National Prize winner from Level 2 (grades 7-8). Raya Kenney of Washington, D.C. wrote to Maya Angelou, author of “Old Folks Laugh.”

Dear Maya Angelou,

“Old Folks Laugh.” How true it is! I love to watch their cloudy eyes crinkle at the edges and lift, just a little. I like to see the spirit come again to their face. I like to watch their drooping cheek lift toward the skies. “When old folks laugh, they free the world,” you wrote in your poem, “Old Folks Laugh,” and I couldn’t lift my eyes from the page. Someone like you, who can take something that seems so small, but make it as big in words as it feels in my heart, becomes an inspiration to me.

Every Thursday I volunteer at a senior’s home. For nearly two years I have worked on the third floor with the people who have worsening cases of Dementia and Alzheimers. It’s hard to watch sometimes as their memory seems to flow away like water. Oh, but how much l love to see them laugh! It’s as if they drank a tall glass of their memories and everything came back. Some days it’s fine and they remember nearly everything, but other days it’s, “Do I know you?”

Your poem seems so selfless. You describe the elders perfectly, with the right touch of play. You sound as though you have watched carefully as their smile becomes a giggle then a full-fledged laugh. You have really helped me notice details. Last week, at the home, I noticed how the seniors’ pants are often a little too big and a little too baggy. I have noticed their yellowing teeth, their scratchy polyester sweaters, and their crooked feet as they struggle with their walkers. I have noticed the faded interior of their rooms and the pictures that memorialize their past scotch-taped to their walls.

Through the richness of your descriptions I have noticed things such as how each elder has their own laugh. Jane, in her wheelchair, tends to lightly titter, while Rosemary, who likes to sew, tends to daintily snort. Robert likes the deep belly laugh where sometimes he can’t catch his breath and I have to pat him on the back. You have made me realize just how much soul they have. I like to watch as the old folks laugh mostly because it makes me happy watching each person be reminded of the incredible parts of their life. I like to think that I share with you the tendency to appreciate the small things. But then again, it isn’t really a small thing when the elderly laugh. To you and I, it is like a bar of gold.

The old folks “generously forgive life for happening to them,” you wrote. Though your poem describes old people laughing, I think the content is covering a deeper meaning. It made me realize the stories behind their smiles and the meaning behind their laughs. Robert might like to laugh as much as he does because he once was in the army during the Great War. Through the desperation, death, and horror he and his friends needed a way to find happiness among the bleak days. Jane grew up in a proper society where laughing too hard was considered improper for a young lady so she titters rather than actually laughing. Some days, it’s like my elderly friends and I are riding the top of a wave on an oncoming laugh. Those are the best days.

Since reading your poem, however, I have also noticed the ones who don’t laugh. I have been quite shocked by that fact. I’ll say something funny and maybe one or two will smile and one might giggle a little, but several others won’t even turn up their lip. I try to convince myself that they still feel well enough to laugh and they simply don’t find me that funny. But I know in my heart of hearts that they have forgotten how to laugh. I try to figure out ways to teach them again, for it is one of life’s greatest pleasures. Because of this, in many ways, reading your poem has inspired me to be a better caretaker of the old and helped me see strength in their fragility. Knowing how delicate they are and how much life they have already lived, how many laughs they have already laughed and how many stories they have lived to tell makes me feel more appreciation for them.

Your poem, though it describes how elders laugh, not only has opened my eyes to their thoughts and feelings, but it has also caused me to think about how they have lived and how their stories have affected them. I’m around these incredible people a lot and I’m very grateful to spend the time with them because I know they have a lot of wisdom to teach me despite their failing memories.

Thank you for writing “Old Folks Laugh.” You have helped me notice and appreciate the stories and the small things, both with the elders and with the simplicities of everyday life. Your poem relates to me so much that it makes me smile to know I’m not the only one who finds pleasure in old folks.

Raya Kenney

You can read all the winning letters here, including the winning letters from previous years.

July 13, 2016

New Online: Website Updates, Presidential Papers, Federal Resources

(The following is a guest post by William Kellum, manager in the Library’s Web Services Division.)

Website Resources

New in July is a new, responsive design for the Library’s Online Catalog, one of the most heavily used features of our website. Like other websites, we’ve seen a dramatic increase in the number of users accessing our content using mobile devices – not only for basic information about the Library but also for research tools like the Online Catalog. The new catalog interface is responsive, resizing the elements on the screen to optimally fit the user’s device, whether phone, tablet, laptop or desktop. The new user interface also simplifies and streamlines page layouts and type styles and improves accessibility for all patrons, including those with disabilities.

[image error]

The new Online Catalog design features clean, mobile-friendly layouts.

New in Manuscripts

From our Manuscript Division comes the Martin Van Buren Papers, one of the 23 collections of presidential papers residing in the Library. Never before online, the new presentation includes access to more than 6,000 items dating from 1787 to circa 1910. The bulk of the material dates from the 1820s, when Van Buren (1782-1862) was a U.S. senator from New York, through his service as secretary of state and vice president in the Andrew Jackson administrations (1829-1837), to his own presidency (1837-1841) and through the decade thereafter when he made unsuccessful bids to return to the presidency with the Democratic and Free Soil parties. Included are correspondence, autobiographical materials, notes and other writings, drafts of messages to Congress in 1837 and 1838 and other speeches, legal and estate records, miscellany and family items. The presentation also includes a handy timeline and a great selection of political cartoons from the collections of the Prints & Photographs Division featuring Van Buren.

Federal Register Resources

The Federal Register is the official daily publication for presidential documents, executive orders and proposed, interim and final rules and regulations, as well as notices by Federal Agencies and notices of hearings, decisions, investigations and committee meetings. The Federal Register has been published by the National Archives and Records Administration since 1936. Our new Federal Register online collection provides access to 14,586 issues of the Federal Register, covering the years 1936-1993. The Law Library of Congress blog provides a Beginner’s Guide that will help users understand the Federal Register and how to use it in research.

New in Exhibitions

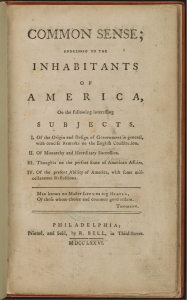

[image error]

The “America Reads” online exhibition includes images from books that shaped America, such as this 1776 edition of Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense.”

In 2012, a group of curators and subject experts in the Library of Congress developed the institution’s popular exhibition, Books That Shaped America. The books chosen were not intended to be a list of the “best” books published in the United States. Rather, the group chose 88 core books by American authors that had, for a wide variety of reasons, a profound effect on American life. Knowing that opinions can be as varied as the number of people you ask, we urged the public to name “other books that shaped America” and to tell us which of the 88 core books on our list were most important to them. That survey forms the basis of a new online (and in-person) exhibition, America Reads. Thousands of readers responded with their choices. The Top 40 vote-getters for “other books that shaped America” are on display, along with the public’s top choices from our original 88 selections.

New Online:

(The following is a guest post by William Kellum, manager in the Library’s Web Services Division.)

Website Resources

New in July is a new, responsive design for the Library’s Online Catalog, one of the most heavily used features of our website. Like other websites, we’ve seen a dramatic increase in the number of users accessing our content using mobile devices – not only for basic information about the Library but also for research tools like the Online Catalog. The new catalog interface is responsive, resizing the elements on the screen to optimally fit the user’s device, whether phone, tablet, laptop or desktop. The new user interface also simplifies and streamlines page layouts and type styles and improves accessibility for all patrons, including those with disabilities.

The new Online Catalog design features clean, mobile-friendly layouts.

New in Manuscripts

From our Manuscript Division comes the Martin Van Buren Papers, one of the 23 collections of presidential papers residing in the Library. Never before online, the new presentation includes access to more than 6,000 items dating from 1787 to circa 1910. The bulk of the material dates from the 1820s, when Van Buren (1782-1862) was a U.S. senator from New York, through his service as secretary of state and vice president in the Andrew Jackson administrations (1829-1837), to his own presidency (1837-1841) and through the decade thereafter when he made unsuccessful bids to return to the presidency with the Democratic and Free Soil parties. Included are correspondence, autobiographical materials, notes and other writings, drafts of messages to Congress in 1837 and 1838 and other speeches, legal and estate records, miscellany and family items. The presentation also includes a handy timeline and a great selection of political cartoons from the collections of the Prints & Photographs Division featuring Van Buren.

Federal Register Resources

The Federal Register is the official daily publication for presidential documents, executive orders and proposed, interim and final rules and regulations, as well as notices by Federal Agencies and notices of hearings, decisions, investigations and committee meetings. The Federal Register has been published by the National Archives and Records Administration since 1936. Our new Federal Register online collection provides access to 14,586 issues of the Federal Register, covering the years 1936-1993. The Law Library of Congress blog provides a Beginner’s Guide that will help users understand the Federal Register and how to use it in research.

New in Exhibitions

The “America Reads” online exhibition includes images from books that shaped America, such as this 1776 edition of Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense.”

In 2012, a group of curators and subject experts in the Library of Congress developed the institution’s popular exhibition, Books That Shaped America. The books chosen were not intended to be a list of the “best” books published in the United States. Rather, the group chose 88 core books by American authors that had, for a wide variety of reasons, a profound effect on American life. Knowing that opinions can be as varied as the number of people you ask, we urged the public to name “other books that shaped America” and to tell us which of the 88 core books on our list were most important to them. That survey forms the basis of a new online (and in-person) exhibition, America Reads. Thousands of readers responded with their choices. The Top 40 vote-getters for “other books that shaped America” are on display, along with the public’s top choices from our original 88 selections.

July 5, 2016

Letters About Literature: Dear Fred Gipson

Last week, we featured the first of two letters that tied for the National Honor Award for Level 1 in the Letters About Literature contest. The initiative is a national reading and writing program that asks young people in grades 4 through 12 to write to an author (living or deceased) about how his or her book affected their lives. Winners for 2016 were announced last month.

The second Level 1 National Honor Award-winning letter comes from Ellie Sanders of Washington, D.C., who wrote to Fred Gipson, author of “Old Yeller.”

Dear Mr. Gipson:

I was born into a poor Chinese family. They gave me up in hopes that I would get a better life. I was adopted when I was a little over a year old. My new family included a jumpy golden retriever pup. His name was Maxwell Silver Hammer Sanders, Max for short. He had floppy ears and furry paws. He was my best bud. From playing spies at naptime (oops) to welcoming a new sister, he was there. He moved three times with us, from Austin to Houston and finally to D.C. He loved to swim and hunt squirrels. He was the one I could trust to listen to my secrets. He never yelled, and he always had a special smile for me. I hoped my life, my world, would continue like this. I thought all was well, which it was, almost. I’m sure that Travis from “Old Yeller” felt the same way.

One night, in my new brick house, in a new place, everything changed. My sister and I had already been put to bed. I heard a thump and some scraping. I crept spy-like out of my bed, by my sister’s room, and down the stairs. The scene that my eyes saw, that my brain took in, sent shivers down my spine. My mom and dad were kneeling over Max. He was breathing heavily. I stepped out from the shadows. My heart led a drumline in a parade. Everything in the world stopped in anticipation. Max had gotten sick before, but the way my mom looked at me I knew that this was different. My mom beckoned me over. Her face was grave. She told me that Max was sick. He was too weak to walk. My mom and dad talked, I couldn’t hear a word they said. I felt like I was underwater. Sounds blurred and my eyes became the tiniest bit bleary. My mom and dad stopped talking; they had reached a conclusion. My mom said, “Max is old, I think it’s time to-.” She started to tear up. She didn’t have to finish. My dad went upstairs to wake my sister. I heard my sister Jillian come and sit down beside me. Mom told her what needed to happen. She started to cry. I felt that numb empty feeling that Travis had felt after he lost Old Yeller. Except it was different for me. I felt the empty feeling before losing Max. Max, my lifetime buddy had been sentenced to death for his own good.

One year after Max’s death, my mom recommended the book “Old Yeller.” The place in my heart that Max held was healing bit by bit. It was like my heart was a puzzle, and the final pieces had been lost. I climbed up the carpeted attic stairs and bent down and picked up an old, wrinkled, yellowed covered book. I got comfy in my reading nook and started to read. I faded into a zone. I was not in the attic, I was in the forest with Travis and Old Yeller hunting gobbler. I was saving Little Arliss from the she bear. Then, my own life started to replay in the book. Max and Old Yeller became the same dog. As I read on, I relived my sorrow.

I exited the book and lay there, thinking. I felt different, like the pieces of my heart finally coming together. It seemed as if I had found the lost pieces to my heart. I finally saw Max’s death in different way. I still miss Max, but now it’s different. Instead, now I think of him as not only my best friend, but an angel always watching and guiding me. “Old Yeller” now holds a special place in my heart. My heart is now whole. That is all thanks to you, Fred Gipson. Thank you.

Ellie Sanders

You can read all the winning letters here, including the winning letters from previous years.

July 4, 2016

How Did America Get Its Name?

Today, America celebrates its independence. Our founding fathers drafted and adopted the Declaration of Independence, declaring America’s freedom from Great Britain and setting in motion universal human rights.

While the colonies may have established it, “America” was given a name long before. America is named after Amerigo Vespucci, the Italian explorer who set forth the then revolutionary concept that the lands that Christopher Columbus sailed to in 1492 were part of a separate continent. A map created in 1507 by Martin Waldseemüller was the first to depict this new continent with the name “America,” a Latinized version of “Amerigo.”

“America” is identified in the top portion of this segment of the 1507 Waldseemüller map. Geography and Map Division.

A crown jewel in the Library’s cartographic collections is the map, also known as “America’s Birth Certificate.” While the map has been much publicized since it was acquired in 2003, it’s worthy of exploration today of all days.

The map grew out of an ambitious project in St. Dié, France, in the early years of the 16th century, to update geographic knowledge flowing from the new discoveries of the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Waldseemüller’s large world map was the most exciting product of that research effort. He included on the map data gathered by Vespucci during his voyages of 1501-1502 to the New World. Waldseemüller named the new lands “America” on his 1507 map in the recognition of Vespucci’s understanding that a new continent had been uncovered following Columbus’ and subsequent voyages in the late 15th century. An edition of 1,000 copies of the large wood-cut print was reportedly printed and sold, but no other copy is known to have survived. It was the first map, printed or manuscript, to depict clearly a separate Western Hemisphere, with the Pacific as a separate ocean. The map reflected a huge leap forward in knowledge, recognizing the newly found American landmass and forever changing mankind’s understanding and perception of the world itself.

For more than 350 years the map was housed in a 16th-century castle in Wolfegg, in southern Germany. The introduction to Waldseemüller’s “Cosmographie” actually contains the first suggestion that the area of Columbus’ discovery be named “America” in honor of Vespucci, who recognized that a “New World,” the so-called fourth part of the world, had been reached through Columbus’ voyage. Before that time, there was no name that collectively identified the Western Hemisphere. The earlier Spanish explorers referred to the area as the Indies believing, as did Columbus, that it was a part of eastern Asia.

The Library has plenty of other resources on Waldseemüller and the map, including videos and a pretty cool story regarding the institution’s partnership with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in building a hermetically sealed case for the priceless map. You can also read about the project on the NIST site.

July 1, 2016

Pic of the Week: Familiar Faces on Display in Atlanta

The following is a guest post by Lisa A. Taylor, Liaison Specialist for the Library of Congress Veterans History Project (VHP).

One of the many joys of working at the Veterans History Project is discovering all of the out-of-the-box ways researchers find to use the collections. VHP’s congressional mandate is to collect, preserve and make accessible the war stories of America’s veterans so that future generations may hear directly from veterans and better understand the realities of war. It is the “make accessible” part of the mission that I find particularly fascinating, because as soon as that phase is complete, it is the individual research interests that inform what happens next. The researchers who access VHP collections are not just historians, authors and documentarians. Sometimes we get inquiries from artists, medical professionals, law firms and performance troops—people and organizations you probably would not assume have an interest in war or veterans’ personal accounts.

Wall display at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta Airport featuring photos from VHP collections. Photo by David Vogt.

One example of an out-of-the-box use of VHP collections comes from none other than Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta Airport, the world’s busiest passenger airport, located 650 miles away from our office. Earlier this year, an airport representative tasked with creating a permanent tribute wall to honor the men and women of the United States Armed Forces found exactly what he needed as he perused VHP’s online database. After some strategy meetings with VHP staff and carefully following our Copyright permissions process, the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta Airport added 100 photographs from VHP participants’ collections to the tribute wall. How awesome is that? I’d say, very!

The airport unveiled the tribute wall during a public dedication ceremony yesterday, just in time for Independence Day and what is sure to be an even busier travel season. We are honored to have VHP collections featured in such an inventive way—one that takes our mission to accessibility and beyond.

June 28, 2016

Letters About Literature: Dear Kathryn Erskine

We continue our spotlight of letters from the Letters About Literature initiative, a national reading and writing program that asks young people in grades 4 through 12 to write to an author (living or deceased) about how his or her book affected their lives. Winners for 2016 were announced earlier this month.

There was a tie for the national honor award for Level 1. Following is one of the winning letters written by Charlie Boucher of Rhode Island to Kathryn Erskine, author of “Mockingbird.”

Dear Mrs. Erskine,

A few years ago, I was walking down a bustling Boston street when I noticed a man. His clothes were torn, too small, and he clutched a jar labeled “Please donate.” He muttered gibberish to himself, then shouted at a few young ladies. He seemed confused, yet aggravated simultaneously. I was afraid he might try to hurt someone. My father hurried me along, past the man and down the street. I quickly realized I was walking away from something bigger than a man; I was walking away from what my younger, ignorant self considered to be a disease, a sickness. When we were out of earshot, I asked my dad what was wrong with that man. He brushed the question off, simply saying that I should “avoid people like that.” About a month later, I picked up “Mockingbird.”

I fell in love with that book. No other book has ever made me cry. But I did more than cry. I thought, I visualized, I feared. When I finished your book, I couldn’t stop thinking about that man I had seen. Did he have Aspergers? Rather than avoiding him, should my father and I have helped him? What about the countless other Caitlins in the world? I felt sympathy for them, but I felt something else. Later I realized that was guilt.

I was the girls at Caitlin’s school, bringing her down. Just for avoiding people like that, I had become the bully. I was a hypocrite, ridiculing those who did not help others but not actually helping. The very core of my being, kindness, was in question. But I reread your book, and I felt more a sense of understanding. You weren’t trying to frown upon those who bullied, but rather encourage people to be more open, to promote empathy. I did.

Not even a week after my discovery, I was walking into church when I saw a man who looked and seemed similar than the man I had previously met in Boston. I smiled at him, remembering Caitlin, and gave him a high five. It looked like I had made his day. That man continues to go to my church, and I still greet him the same way I did on that first day. I realized he was kind and helpful. He along with that experience, changed me, and kindness has fully emerged again. I am the person I want to be.

But your book did more than that. It brought to me a confusing topic in an enlightening way: Death. Having someone you love or care about violently ripped away from you. Not knowing where to go, or who to turn to, or anything. That struck me, and it stuck. Life is short, and any day it could end. Just like that. Poof. So make the most of it, and assist the unassisted. Help the helpless. Give a voice to the silent.

All these emotions and thoughts, so strong that I couldn’t keep them in, came pouring out when I read your inspirational novel. And thanks to “Mockingbird” I know now, more than I ever have, about bullying, loss, Aspergers. I have emerged from a cloud of swirling sentiments, a better person, better friend. Your book helps me every day to be the person I want to be, and for that I thank you.

Charlie Boucher

You can read all the winning letters here, including the winning letters from previous years.

June 27, 2016

New Online: William Oland Bourne Papers

(The following is a story written by Mark Hartsell for the Gazette, the Library of Congress staff newsletter.)

As a hospital chaplain during the Civil War, William Oland Bourne collected the names of the wounded soldiers he tended and, in doing so, noticed a terrible trend: Many soldiers used their left hands to sign his autograph book because their right arms were missing.

How, Bourne wondered, could these grievously wounded men adapt – to the amputation of their arms, to postwar life, to new jobs – and how could he help?

Bourne had an idea: a left-handed penmanship contest for previously right-handed veterans who suffered the loss of their right arms in combat – a small way to demonstrate self-reliance, adaptability and the skills necessary to find postwar employment.

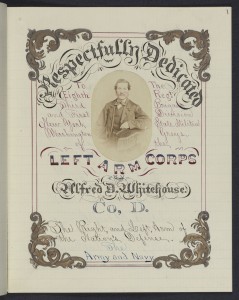

A penmanship sample submitted by Alfred Whitehouse, incorporating his own photo. Manuscript Division.

More than 60 years after the war, the entries in the two contests staged by Bourne found their way to the Library of Congress and, last month, were placed online – a collection of some 1,500 items that includes photographs, pamphlets and nearly all the contest submissions.

The Wm. Oland Bourne Papers were donated to the Library in 1931 by prominent New York bookseller Gabriel Wells.

“The penmanship contest entries in the Bourne collection not only provide evidence as to the experiences of Civil War soldiers who lost limbs during that war specifically, but they also speak to a longer history of the reintegration of wounded veterans back into civilian life and the different ways individual veterans interpret their military service,” said Michelle Krowl, a historian in the Manuscript Division.

In addition to his work as a chaplain, Bourne served as editor of The Soldier’s Friend, a newspaper dedicated to veterans’ needs and published late in the war and for several years after. He saw firsthand the terrible injuries suffered by Union soldiers and sailors and witnessed their efforts to adapt to disability – experiences that inspired his penmanship contests.

Men who had been right-handed before the war – particularly those who had performed manual labor – might need a new line of work. The contest, Bourne thought, might help them demonstrate their adaptability, that they had the skills to support themselves.

“Penmanship is key to getting a government position,” a contest ad in The Soldier’s Friend read.

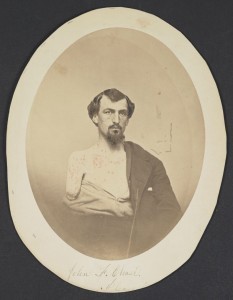

Penmanship contest participant J.S. Pendergrast. Manuscript Division.

The contests offered cash prizes and emphasized the quality of penmanship. They attracted hundreds of entrants – not all of whom precisely fit the criteria.

Lewis Horton lost both arms in a naval accident. Undeterred, he entered a letter – certified by a justice of the peace – that he claimed he wrote using his teeth.

Pvt. J.S. Pendergrast of the 24th Massachusetts Infantry lost his right arm – and two fingers and part of the thumb on his left hand. The judging committee awarded him $20 for a letter produced under “exceptional circumstances.”

In some entries, the penmanship is remarkably neat, the letters well-formed and the presentation even artistic. Alfred D. Whitehouse produced an elaborately illustrated page bearing his photograph and dedicated to the “Left Arm Corps.”

In others, the difficulty adapting is plain. “For some, it’s more halting and it’s clear that it’s a struggle for them,” Krowl said.

Some veterans filled their entries with poetry, some simply copied text to demonstrate their penmanship. Most, however, told their own stories.

Pvt. John F. Chase of the 5th Maine Artillery received a Medal of Honor for heroic action during the Battle of Chancellorsville in spring 1863 and was badly wounded atGettysburg two months later.

Chase lay untended on the battlefield for two days and, after being picked up, received no medical attention for three more – doctors assumed he had no chance to survive.

Penmanship contest participant John Chase. Chase identified his many wounds with pen marks on the photo. Manuscript Division.

But he did, and he described his experiences in his contest entry – a letter accompanied by a photograph on which Chase marked his many wounds in red pen.

“I lost my right arm near the shoulder, and left eye,” Chase wrote, “and have forty other scars upon my brest and shouldr caused by peaces of fragments of a Spharical case shot, at the battle of Gettersburg, july the seccond 1863.”

John Bryce of the 1st New York Volunteers described the surgical amputation of his arm – and the effects of anesthesia – in an essay titled “How I Felt Under Cloriform.”

“Set sail as a vessel sailing through the air,” Bryce wrote. “I had a narrow river to cross, which seemed very deep. … I felt no pain during the cutting of my arm. It seemed pleasant while in the stupor.”

The first contest closed in February 1866 with an exhibition of nearly 300 entries at a New York hall festooned with inspirational banners: “Disabled but not disheartened,” “Our disabled soldiers kept the Union from being disabled.”

The display drew big crowds and many dignitaries, including Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Maj. Gen. O.O. Howard, who himself lost his right arm at the Battle of Seven Pines in 1862.

The first contest was such a hit that Bourne decided to stage a second competition in 1867.

For that contest, Bourne enlisted major Civil War figures – among them, Grant, Adm. David Farragut and Gens. William T. Sherman, Philip Sheridan and George Meade – to each choose a prizewinner and write a letter to him.

“While we have been accustomed to regard the loss of the right arm as almost fatal to a useful, and consequently happy life,” Sherman wrote to contestant Caleb Fisher, “these samples show how nature substitutes wisely and well one other arm.”

A century and a half later, Krowl said, those letters do something more – Bourne’s contest unintentionally preserved stories that otherwise might never have been told.

“This might be the only place their recollections are captured,” Krowl said. “Unless they filed for a pension and gave their life stories in their claims, this may be the only place they told their life stories or expressed what they felt about losing their arms.”

June 24, 2016

Pic of the Week: Country Crooners

(from left) Kristian Bush, Charlie Worsham and Jim Collins perform at the Country Music Association Song Writers Series concert in the Coolidge Auditorium. Photo by Shawn Miller.

The Country Music Association and Library of Congress Music Division joined forces again to bring the CMA Songwriters Series to the Library’s historic Coolidge Auditorium. This year’s concert featured Kristian Bush of the hit country duo Sugarland, along with Jim Collins and Charlie Worsham.

Launched in 2005 at Joe’s Pub in New York City, the CMA Songwriters Series gives fans an intimate look at where the hits they love come from. For a decade, the CMA Songwriters Series has been exposing fans across the country and the globe to the artisans who, through their craft, pen hits that touch the lives of millions of music fans. Since it launched at Joe’s Pub, the series has presented more than 75 shows in 13 cities, including Boston, Belfast, Dublin, Los Angeles, Paris, Phoenix, and Washington, D.C.

You can watch last year’s performances here.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers