Library of Congress's Blog, page 121

December 13, 2016

Rare Item of the Month: Mary’s Treasures

(The following is a guest blog post written by Elizabeth Gettins, Library of Congress digital library specialist.)

[image error]

Mary Todd Lincoln’s seed-pearl necklace and matching bracelets. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

This month, in honor of Mary Todd Lincoln’s birthday on December 13, we will depart from our literary theme and look at some of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division’s “special collections.” While these items are not rare books, they are every bit as valuable.

Abraham Lincoln gifted his wife Mary Todd Lincoln nothing less than Tiffany to wear for the first inaugural ball of his presidency. This exquisite necklace and two bracelets came to the Library in 1937 as part of the gift from Lincoln’s granddaughter, Mary Lincoln Isham, and have been incorporated into the Stern Collection of Lincolniana.

President Lincoln purchased the items at Tiffany’s in Manhattan. The Prints and Photographs Division has this Matthew Brady photograph of Mary Todd Lincoln wearing the jewelry gifted to her by Lincoln, as well as the ball gown that she wore to Lincoln’s first inaugural ball. She must have felt every bit the part of first lady wearing such finery.

The product of a wealthy Kentucky family, Mary attended Madame Mantelle’s Finishing School, which concentrated on French, literature, dance, drama, music and social graces. With this background of refinement, she must have cherished the beauty of the jewelry and appreciated the quality of the maker. The use of seed pearls in fine jewelry throughout the latter part of the 19th century was a popular practice. They often adorned brooches, tiaras, pins and earrings and were a staple of Victorian fashion. Many prestigious jewelers made prolific use of seed pearls as they were a sign of taste and status.

[image error]

Mary Todd Lincoln. Photo by Matthew Brady, 1861. Prints and Photographs Division.

The online Stern Collection of Lincolniana provides a fascinating glimpse into Lincoln’s life and presidency and contains more than 4,000 items. One of the great advantages of digitized collections is that it has made it nearly effortless to search a large volume of items quickly to draw together like items on any topic or date. Searching on the term “inaugural ball” draws up the result of this dance card for the 1861 ball. Viewing this dance card, the photograph of Mary Todd Lincoln in her inaugural ball finery and the Tiffany jewelry allows one to go back in time that March evening nearly 156 years ago. One is offered a slice in time and can imagine the excitement and sense of promise that the evening must have held for Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln.

Further, searches on “Mary Todd Lincoln” bring up some fascinating results from the online collection. One can get a glimpse into Mary’s personality and character by reading the letters she wrote and received, as well as studying the various portraits rendered in her likeness.

[image error]

Dance card for Lincoln’s inaugural ball, 1861. Rare Book and Special Collections Division

For example, this letter to Brig. General Sickles, dated Sept. 31, 1862, finds Mary Todd Lincoln attempting to schedule a meeting with Sickles while commenting on continuing cannon fire heard at the White House. She expresses concern about the war and not wanting to upset President Lincoln with her thoughts on the topic.

In this letter from Queen Victoria, dated April 1865, the queen expresses condolences about President Lincoln’s death.

“[I] must personally express my deep and heartfelt sympathy with you under shocking circumstances of your present – dreadful misfortune. No one can better appreciate, than I can, who am myself utterly broken hearted by the loss of my own beloved husband, who was the light of my life, my stay, my all, – what your own sufferings must be, and I earnestly pray that you may be supported by Him, to whom alone the sorely stricken can look for comfort in their hour of heavy affliction.”

This letter to Leads and Miner from Nov. 11, 1865, expressed consternation that her children’s tutor sold items for profit that were given to him by Mary Todd Lincoln.

“As to Mr. Williamson – for the last four years, he was tutor to my little boys; my husband & myself always regarded him as an upright, intelligent man – when leaving Washington, last May I directed, the servant woman, to present him in my name (and in consideration, for the high reverence, he Mr. W. always entertained for the President) a shawl & dressing gown. In doing so, I felt he would cherish & always retain, these relics of so great & good a man – My astonishment, was very great I assure you, when you mentioned that these articles were for sale. Mr. W. certainly did not reflect, when he proposed such a thing. I wish you would write to him & remonstrate – upon so strange a proceeding.”

Bringing these assorted items together help us form a better understanding of the multi-dimensional person that the first lady was and honor her on her December birthday. She was a woman who may have endured heavy burdens throughout her adult life, yet she strove to find the lighter side through the delight and refinement afforded to her position as first lady.

December 12, 2016

10 Reasons You Should Want To Be A Junior Fellow

(The following is a guest post written by Kaleena Black, program manager for the Junior Fellows Summer Intern Program.)

Are you thinking about applying to the Library of Congress Junior Fellows Summer Intern Program, but aren’t quite sure? The program is a 10-week paid fellowship for undergraduate and graduate students who will work full-time with Library specialists and curators to inventory, describe and explore collection holdings and to assist with digital-preservation outreach activities throughout the Library. Fellows will be exposed to such Library work as collection processing, digital preservation, educational outreach, access, standards-setting and information management. More information can be found here.

Still not sure? Well, here are 10 reasons why we think you should!

Spend a summer in Washington, D.C.

Working, networking and experiencing all that the nation’s capital has to offer.

Gain valuable professional experience.

The program offers in-depth opportunities for career development and exploration, through an array of exciting projects.

A great research opportunity on the east coast.

No matter your interest, the fellows can get real “Indiana Jones” with our collections. (Think: researching rare collections, exploring stereographs and daguerreotypes, testing paper samples, producing digital bags, buckets and portals.)

Cool curators and trailblazing technicians.

Collaborate with and receive mentorship from world-class curators and top-notch technicians. (Seriously, the Library staff is some of the greatest.)

Friends in your field.

Connect with a cohort of talented, motivated undergraduate and graduate students from across the country.

Gain an edge.

Participate in tours, cutting-edge seminars, meet-and-greets and other enrichment activities. Enhance your summer experience and supplement all the cool project work that you’ll be doing.

Money

This internship offers a stipend.

Making a mark.

Showcase your project achievements and discoveries through opportunities like Display Day, blogs, lightning talks or panel discussions.

Access to Washington, D.C.’s most “beautiful” building.

Did we mention that you get to work at the Library of Congress, an unbelievable treasure chest of history, culture, creativity and knowledge? You’ll get some amazing, behind-the-scenes access to the largest library in the world. Plus, you’ll be contributing to the legacy of work at this truly awe-inspiring cultural institution.

It’s really fun!

Enough said.

Convinced yet? Then visit our website for more details about the program or head straight to USAJOBS for the application.

Support the 2017 Book Festival

Gene Luen Yang and Stephen King at the 2016 Library of Congress National Book Festival. Photo by Ellis Brachman

(The following is a guest post from Sue Siegel, director of development at the Library of Congress.)

To Stephen King, the master of horror, a truly frightening scenario is the emergence of a world of non-readers. King, a champion of literacy recognized by the Library of Congress, says that reading is critical to opening up our abilities to empathize and analyze — skills that are essential to being an informed thinker and better human being. He has made it part of his life’s work to inspire young audiences to read so they may know “learning to think is a result of hard work and steady effort.”

He is justified in being afraid. Across America, the statistics about the state of literacy and reading are heartbreaking:

The U.S. is ranked 12th in literacy among 20 “high income” countries.

44 million adults are unable to read a simple story to their children.

50% of adults cannot read a book written at an eighth grade level.

Illiteracy costs American taxpayers an estimated $20 billion each year.

Source: National Institute for Literacy, National Center for Adult Literacy, The Literacy Company, U.S. Census Bureau

To promote a culture of reading and literacy at the national level, the Library of Congress presents the annual National Book Festival — a booklover’s dream come true. Each year, hundreds of thousands of booklovers of all ages and backgrounds have the opportunity to meet their favorite authors and snag autographs (popular graphic novelist Raina Telgemeier managed to autograph 1,500 books in an hour and 10 minutes!) from such luminaries as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Candice Millard, Bob Woodward, Ken Burns, Salmon Rushdie, and Kwame Alexander, in-person and virtually, entirely free of charge.

{mediaObjectId:'43792574E2CB01DEE0538C93F11601DE',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

The Library of Congress National Book Festival is only possible because of donors who share a commitment to advancing reading and combatting illiteracy.

Please make a gift today to help create a nation of readers, and mark your calendar for Sept. 2, 2017, for next year’s National Book Festival.

December 9, 2016

Pic of the Week: Pulling Strings

Luthier John Montgomery. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Luthier John Montgomery inspects the strings on the 1697 “Castelbarco” cello made by Cremonese master Antonio Stradivari, one of five Stradivari instruments originally donated to the Library by Gertrude Clarke Whittall in 1935. According to her bequest, the instruments would be played from time to time, as they were intended. To that end, she established the Whittall Foundation, an endowment to finance professional in-house use of the instruments and concerts for the public.

John Montgomery is fully trained in both instrument making and restoration and has been working since 1977 when he began as a Watson Fellow studying Hurdy Gurdy construction in France. He attended the Violin Making School of America in Salt Lake City, Utah, and trained under William Monical in New York City. He has been a member of the American Federation of Violin and Bow Makers since 1987. In 1983, he established John Montgomery Inc. in Raleigh, N.C.

December 7, 2016

World War I: On the Firing Line With the Germans (1915)

On the Firing Line With the Germans advertisement, Moving Picture World, 26 February 1916

(The following post was written by Mike Mashon of the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division and originally appeared on the Now See Hear! blog.)

During the centenary observance of World War I, we’ve been prioritizing the preservation of films in our collection pertaining to the conflict. Foremost among these is a film called “On the Firing Line With the Germans,” shot in 1915 by William H. Durborough and his cameraman Irving Ries. Library staff members George Willeman and Lynanne Schweighofer reviewed and selected the best surviving scenes from among 32 reels of nitrate film, nine reels of paper print fragments, and supplemental 35mm from the National Archives, then assembled the digital files created from them to present a complete version of the film as it premiered on 28 November 1915. This description hardly does justice to the hundreds of hours required to restore this film, a complex and exacting process we’ll describe more fully in a future post.

Our restoration could not have happened without the indefatigable research conducted by independent researchers James Castellan and Ron van Dopperen, plus former Library of Congress Moving Image Curator Cooper Graham. In 2014 the trio co-authored “American Cinematographers in the Great War,” which was published by John Libbey and sponsored by the Pordenone Silent Film Festival, where in October 2015 the film was publically shown for the first time since its last documented showing in March 1917. It will be screened again on November 16 here at the Packard Campus, with pianist Stephen Horne accompanying.

Ron was kind enough to synopsize the history of the film for Now See Hear!, but a fascinating and much more comprehensive report—which Castellan, van Dopperen, and Graham call “On the Firing Line With the Germans: A Film Annotation”—can be found here.

In April 1915, the persuasive and enterprising still photographer Wilbur Henry Durborough and cinematographer Irving Guy Ries crossed the border between Holland and Germany in a large, flamboyant Stutz Bearcat to photograph the Great War from the German side. They were to have a great and unique adventure.

[image error]

Durborough and his Stutz Bearcat, courtesy Prints & Photographs Division

Their task was to film Germany at war. The Germans knew they were losing the propaganda battle in the still-neutral United States, and were anxious to have American correspondents document and publicize their point of view. In addition, a group of businessmen in Chicago, a center of pro-German sentiment in the United States, saw an excellent business opportunity in making a war film for American theaters. While the Newspaper Enterprise Association financed Durborough’s wartime photographs, an ad hoc War Film Syndicate financed the duo’s motion pictures.

They filmed in wartime Berlin and East Prussia capturing some poignant footage of life in Berlin, including military hospitals, as well as the destruction in East Prussian cities. Durborough filmed Friedrich von Bernhardi, perhaps the most sword-rattling German militarist of them all, as well as extremely rare footage of the feminists Jane Addams, Alice Hamilton and Aletta Jacobs, who had come to Berlin for the opposite reason: peace.

Durborough and Ries were fortunate to be in Germany in the summer of 1915, during the great German drive across East Prussia and Poland which drove the Russians back to their own border. It was the high-water mark of German forces on the eastern front. For most of this time, Durborough and Ries were accompanying Hindenburg’s forces. They would be present at the fall of Novo Georgievsk, the major Russian fort in Poland, and at the Kaiser Review that followed, where Wilhelm reviewed and thanked his troops on their victory and Durborough caused a stir when he disobeyed orders and filmed Kaiser Wilhelm. He also photographed the fall of Warsaw to the Germans, and its Jewish quarter.

The film is unique in being the only American feature-length documentary made during World War I. It is doubly special because, unlike most other films of the period, it was not cut to pieces for stock shots. It also reflects indirectly the financial and ideological forces at work in the United States at the time. Although probably not the intent of the film makers, it shows horrors of war that were impacting not just the battlefields but also the German home front.

On the Firing Line With the Germans (William H. Durborough, 1915)

{mediaObjectId:'3F2A67398D4300F0E0538C93F11600F0',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

World War I Centennial, 2017-2018: With the most comprehensive collection of multi-format World War I holdings in the nation, the Library of Congress is a unique resource for primary source materials,education plans, public programs and on-site visitor experiences about The Great War including exhibits, symposia and book talks.

December 6, 2016

Technology at the Library: Getting the Whole Picture

(The following is from the November/December 2016 Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, and was written by Phil Michel, digital project coordinator in the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division.)

A new, oversize scanner is putting the Library’s collection of panoramic photographs in focus.

One of the great joys in looking at a panoramic photograph is finding small details in a picture that can be several feet in length and show an entire city, or the whole crew of a battleship. It’s an experience that’s hard to reproduce in a smaller space, such as in a book or on a computer monitor or on a magazine page. But new viewing technologies let us zoom in and pan around to see the fascinating details, on computers and mobile devices. And new scanning technologies are helping the Library produce higher-quality digital images in a single exposure.

The Library’s Panoramic Photograph Collection contains more than 4,000 of these richly detailed photographs, most from the early 20th century, when panoramas were at the height of their popularity. They include cityscapes, landscapes and group portraits from all 50 states and several other countries.

They document the nation, its enterprises and its interests such as agricultural life; beauty contests; disasters; such engineering work as bridges, canals and dams; fairs and expositions; military and naval activities, especially during World War I; the oil industry; schools and college campuses; sports; and transportation. Ranging in length from 28 inches to six feet, the panoramic photographs were acquired when photographers submitted copies of their works to the U.S. Copyright Office in the Library of Congress for copyright protection.

The Library first began reproducing the panoramas in the 1990s by taking photographs of overlapping segments and then “stitching” the sections together to show the whole image on laser videodiscs in the Prints and Photographs Division Reading Room. Later, these copy photographs were converted to digital files and re-stitched to make them accessible on the Library’s website. The process was labor-intensive and the panoramas fit nicely on a screen, but it was difficult to see small features.

Now, with a recently acquired oversized flatbed scanner, the Library is capturing entire panoramas (up to 6-½ feet long) in a single pass exposure and at higher levels of resolution, so every little detail can be seen clearly. The Library relies on standard techniques that were developed with other government imaging experts to produce the best image possible. Using an image target with wine lines and color patches, the Library can check the scanner for sharp focus and lighting balance and ensure that the colors are accurately reproduced in the scan.

The image quality of the newly scanned panoramic photograph of Buffalo, New York, showing Genesee and Main Streets was greatly enhanced using a new, atbed scanner. W.H. Brandel, 1911, Prints and Photographs Division.

You can read the November/December 2016 issue in its entirety here, along with issues from previous years.

December 5, 2016

Library in the News: November 2016 Edition

Smokey Robinson made headlines as the Library celebrated his work and career during the Gershwin Prize for Popular Song celebration concert.

“Amid multiple standing ovations from an audience filled with political dignitaries at DAR Constitution Hall, the Motown star reflected on his humble Detroit roots as he accepted the prestigious Gershwin Prize for Popular Song,” wrote Brian McCollum for the Detroit Free Press.

Robinson had previously spoken with McCollum about the honor on the eve of the concert.

“If I’m being even mentioned in the same breath with the Gershwins — whose music is everlasting — then that’s a crowning achievement for me as a songwriter. I want to be Beethoven, man. I want to be Bach, Chopin,” he said. “Five hundred years from now, they’ll still be playing Smokey Robinson music: If possible, that’s what I want to be. So this is the first step.”

“Robinson’s songs — whether written for himself and the Miracles or other Motown artists — have soundtracked so many lives because of their emotional universality. They transcend time, space, performer and genre, and the event was programmed to illustrate that fact,” said Chris Kelly for The Washington Post.

In a special video presentation, the Post featured fans reminiscing on their favorite Smokey Robinson songs and how his music affected their lives.

“The audience sang and clapped along to “My Girl,” the night’s show closer, as a testament to Robinson’s enduring compositions,” reported Joshua Barajas for PBS NewsHour.

Other stories ran on CBS, WTOP, Billboard and Broadway World, among others.

Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden continued to make headlines in November.

“At different times in the library’s history, the people who have served as Librarian of Congress—scholars, librarians, lawyers—have each brought different skills,” she says. “As a librarian, I might have experiences to bring as the library faces a new part of its history, and a lot of that has to do with technology and accessibility,” Hayden told Greg Landgraf of American Libraries Magazine.

Hayden also spoke with Rebecca Sutton of NEA Arts Magazine. “I’m just discovering the depth of the collection. I think the arts community would be very pleased by the treasures here. I’m looking at photography books now: One’s a book on lighthouses; there are others on canals, dance, furniture, documentary. It’s like being in a treasure chest,” Hayden said. “It’s a beautiful place, but it has beautiful things too. Not just beautiful, but things that make you think.”

Eric Weibel, kid reporter for Scholastic, sat down with Hayden to talk about the Library and her thoughts on children’s literature and literacy.

The Librarian also spoke with Maryland Public Television. You can see the interview beginning at the 16:16 mark.

The Library’s Veterans History Project also received media coverage in November.

Michael Ruane of The Washington Post wrote a story about the project’s online presentation, “The Art of War.”

“The collection highlights the art of servicemen and women whose only canvas was the paper they might have in their pockets,” he wrote. “It captures the mundane and dreary aspects of war, as well as the dignity of its participants, and the drama of its battles.”

Several regional outlets shared stories of collecting efforts, including New Hampshire Public Radio, the Chicago Tribune, The Sentinel Record and Tucson News Now.

December 2, 2016

Pic of the Week: A&E Makes Donation to VHP

Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden and Veterans History Project Director Karen Lloyd present a certificate of appreciation to A&E Networks President and General Manager Jana Bennett following the donation of Pearl Harbor veterans’ oral histories. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Staff from A&E Networks’ HISTORY stopped by the Library this week to donate interviews from some of our nation’s oldest World War II veterans — specifically those who witnessed the attack on Pearl Harbor. On the eve of the attack’s anniversary, these stories offer meaningful testimony to the American entry into World War II.

These 25 A&E oral history recordings will complement more than 250 VHP Pearl Harbor collections.

There are many evocative manuscripts and recordings among these collections, including Leon Jenkins’ diary. He witnessed the Attack on Pearl Harbor and although his diary begins in 1942, its pages are nothing less than evocative.

Owen Edward Rogers contributed to this post.

December 1, 2016

New Online: Presidents, Teachers & More Website Updates

(The following is a guest post by William Kellum, manager in the Library’s Web Services Division.)

From the Thomas Jefferson Papers, a draft of Jefferson’s 1804 Inaugural address, in Jefferson’s own hand. Manuscript Division.

Presidential Collections

With the next presidential inauguration quickly approaching, we’ve updated a popular presentation from our old American Memory site on U.S. presidential inaugurations: “I Do Solemnly Swear…” A Resource Guide highlights items from the Library’s collections such as diaries and letters written by presidents and those who witnessed the inaugurations, handwritten drafts of inaugural addresses, broadsides, inaugural tickets and programs, prints, photographs and sheet music.

For Teachers

New for educators is a major overhaul of the popular Thanksgiving Primary Source Set, which has been updated with new content and a revised Teacher’s Guide. We’ve also put this set together as a Student Discovery Set for the iPad. You can see the full list of Student Discovery Sets on the teacher’s site.

Website Updates

Following up on our big home page and user experience improvements release last month, we continue to modernize key parts of the Library’s website. News from the Library of Congress is now updated with a simplified design of our news releases to make the content easier to read and use on all devices. We’ve also gone back and touched up the data for thousands of news releases going back to 2001, making it possible to filter searches of news items by topic.

Last month, we completed the latest release of the Legislative System of the United States, Congress.gov. The release included enhancements to the homepage, alerts and saved searches, legislation, Congressional Record and Congressional Record Index, committee reports and new capabilities for the advanced search form for legislation. You can see a full list of changes or check out the Law Library’s detailed blog post on the release.

November 29, 2016

Ladies Behind the Lens

(The following is an article, written by Brett Carnell and Helena Zinkham of the Prints and Photographs Division, for the November/December 2016 Library of Congress Magazine.)

“If one is the possessor of health and strength, a good news instinct … a fair photographic outfit, and the ability to hustle, which is the most necessary qualification, one can be a news photographer.”

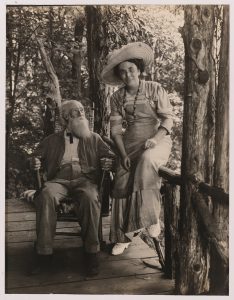

Jessie T. Beals, West Park, New York, 1908.

So said Jessie Tarbox Beals in a 1904 interview with a St. Louis newspaper. Beals was known as America’s first female news photographer because The Buffalo Inquirer and The Courier hired her as a staff photographer in 1902. For most of her career, Beals worked as a freelance news photographer.

News photography is a great strength of the Library’s collections, but work by women photojournalists can be hard to find among these millions of pictures. A new Library web presentation, “Women Photojournalists,” sheds light on these talented individuals through a series of 28 biographies written by Beverly Brannan, photography curator in the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division.

For almost 100 years, newspapers and magazines relied primarily on male photographers because photojournalism was seen as physically demanding work considered too rough for women. As a result, many of the women who succeeded in this field had remarkable life stories as well as skill with the camera. Brannan explores their contributions to the field of photojournalism, tracing their work behind the camera from the advent of photojournalism in the late 19th century up to today. The biographies provide insight into the challenges faced by women photographers as well as their achievements in American photojournalism.

Women photojournalists had at least two things in common—they were willing to push hard to succeed and they wanted to tell stories through pictures. Beyond that, the women’s backgrounds are as diverse as the subjects they documented. Many needed to earn a living, but quite a few were financially independent. Many had a college education or formal training in art, but others came to photography through family interests. Several gravitated to war zones or social justice issues, while others focused on local events and daily life.

The new site builds on “Women Come to the Front,” a 1995 Library exhibition that featured eight women photojournalists who covered war: Therese Bonney, Toni Frissell, Marvin Breckinridge Patterson, Clare Boothe Luce, Janet Flannery, Esther Bubley, Dorothea Lange and May Craig.

Frances Benjamin Johnston shows children her Kodak camera, circa 1900.

“While preparing an overview of the Prints and Photographs Division’s collections, I realized that women had played a more prominent communications role during the Second World War than seemed to be appreciated by those studying the era,” said Brannan, who curated the exhibition.

In the new web presentation, Brannan includes gifted women from every generation of photography, including some like Frances Benjamin Johnston and Toni Frissell, whose papers are housed in the Library of Congress.

Johnston’s family’s social position in Washington, D.C., gave her access to the presidential administrations of Benjamin Harrison, Grover Cleveland, William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt and other notables, which helped launch her career as a portrait photographer and photojournalist with the Bain News Service. Her interest in social justice is reflected in her images of such vocational institutions as Hampton Institute in Virginia and the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. In the 1910s and 1920s, her photographs of estates and gardens around the country illustrated her lecture series titled “Our American Gardens.”

Toni Frissell in Red Cross Uniform, 1942.

Frissell is best known for her high-fashion photography for Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. But during World War II, she used her connections with society matrons to aggressively pursue wartime assignments at home and abroad.

“I became so frustrated with fashions that I wanted to prove to myself that I could do a real reporting job,” Frissell said.

Charlotte Brooks was only one of a handful of women hired as a full-time staff photographer at Look magazine, where she mostly covered home and family life in post-war America. Her work is well-represented in the Look Magazine Photograph Collection in the Library of Congress, having worked for the magazine for 20 years, until the publication ceased in 1971.

The website includes such contemporary photojournalists as Brenda Ann Kenneally, Susan Meiselas and Marilyn Nance, whose careers began in the final decades of the 20th century. Their focus is on people—like those affected by Hurricane Katrina, those forced from their homes in Northern Iraq and working-class people in African-American communities.

“Photography should not be about the photographer,” said Meiselas when she spoke at the Library of Congress.

Yet the images produced by these women reflect their indomitable spirit and worldview.

All photos from the Prints and Photographs Division

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers