Library of Congress's Blog, page 119

February 2, 2017

Curator’s Picks: Surrogate First Ladies

(The following article is featured in the January/February 2017 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

Manuscript Division specialists Julie Miller, Barbara Bair and Michelle Krowl discuss some non-spousal first ladies.

Martha Jefferson Randolph

Martha Jefferson Randolph

Because Thomas Jefferson was a widower when he became president, Dolley Madison, along with his daughters Martha Randolph and Maria Eppes, helped him entertain. Jefferson did not believe that women should participate in politics, as he had seen them do in Revolutionary Paris, so his daughters’ role at his dinners was mainly ornamental. Not so Dolley Madison, who seated herself at the head of the table when she became first lady.

Sarah Yorke Jackson

Sarah Yorke Jackson

Andrew Jackson was newly widowed when he came to the White House in March 1829. He was helped in his hosting duties by his daughters-in-law, Emily Donelson and Sarah Yorke Jackson. Emily, his wife’s niece, was married to his foster son and his presidential secretary A. J. Donelson. Sarah was the wife of his adopted son. Sarah continued as hostess following Emily’s death near the end of Jackson’s second term in office.

Angelica Singleton Van Buren

Angelica Singleton Van Buren

Martin Van Buren was a widower when he became president in 1837. He was aided in White House social functions by his daughter-in-law Angelica Singleton Van Buren, the wife of his son Abraham. Former First Lady Dolley Madison had been their matchmaker. Angelica was well-tutored in the social graces, having attended a female academy in South Carolina and a French school in Philadelphia.

Harriet Lane

Harriet Lane

James Buchanan was a bachelor when he became president in 1857. His niece, Harriet Lane, for whom he was legal guardian, managed social events in the White House. While Buchanan had a troubled presidency, Harriet is ranked among the most popular first ladies. She used her position to promote music and the arts and to advocate various reform causes – setting a trend for first ladies of the future.

Rose Cleveland

Rose Cleveland

Grover Cleveland first entered the Executive Mansion in 1885 as a bachelor and consequently hostess duties fell to his sister, Rose Elizabeth Cleveland. A scholar, lecturer and teacher by training, the feminist Rose continued her intellectual pursuits while first lady and in 1885 published “George Eliot’s Poetry and Other Studies.” President Cleveland’s June 1886 White House wedding to the young Frances Folsom ended Rose’s tenure as first lady, and she gladly returned to her successful literary career.

All photos are from the Prints and Photographs Division.

February 1, 2017

New Online: Sigmund Freud Collection

(The following is written by Margaret McAleer, senior archives specialist in the Manuscript Division.)

[image error]

Sigmund Freud, 1856-1939. Manuscript Division.

Sigmund Freud went digital today with the release of an online edition of the Library of Congress’s Sigmund Freud Collection. Freud’s explorations into the unconscious and founding of psychoanalysis profoundly influenced modern cultural and intellectual history, securing his place in the history of human thought, as Princess Marie Bonaparte once wrote of her analyst and mentor. The collection that was previously available only in Washington is now accessible to the world in a way that it never was before. The online collected was funded by a generous grant from The Polonsky Foundation.

Visitors to the site will have access to a remarkable collection with an equally remarkable history. In 1951, a dozen years after Freud’s death, a group of New York psychoanalysts established the Sigmund Freud Archives to collect and preserve his letters and writings. They selected the Library of Congress as the collection’s permanent home, sending the first installment of material to Washington in the summer of 1952. Many more donations followed. Freud’s colleagues, students, patients and family members – most notably Anna Freud – gave original Freud letters and other items in their possession. Also added to the collection were hundreds of interviews with people who had known Freud personally. The interviews were conducted mostly in the 1950s by K. R. Eissler, founding secretary of the Sigmund Freud Archives.

The online edition comprises the personal papers of Freud and members of his family. It includes correspondence, manuscripts of Freud’s writings, calendars, notebooks, legal documents and certificates, and Freud’s pocket watch, among many other items. Also available online are transcripts of the Eissler interviews, more than a hundred of which are newly opened and available for the first time. Omitted from the online collection is a large supplemental file of secondary source material that largely dates after Freud’s death.

The contents of more than 2,000 folders is available digitally, most of it in German. Below is just a sampling of what researchers will discover.

[image error]

Good conduct certificate, 1859. Manuscript Division.

Good conduct certificate, 1859: Freud’s parents Jacob and Amalia Freud decided to move their family from Moravia to Leipzig, Germany, in 1859, taking up temporary residence in Leipzig during the city’s Easter fair in May. Permanent residence, however, required the approval of city officials, which was far from certain given the legacy of restrictions on the settlement of Jews in Saxony. Jacob Freud, a wool and textile merchant, solicited character and business references to strengthen his case, including this certificate attesting to the family’s good reputation. Despite such testimonials, Leipzig officials rejected Jacob Freud’s application, and the family settled instead in Vienna, Austria. Anyone interested in the events surrounding the Freud family’s move from Moravia will want to read Michael Schröter and Christfried Tögel’s article, “The Leipzig Episode in Freud’s Life (1859): A New Narrative on the Basis of Recently Discovered Documents,” Psychoanalytic Quarterly 76 (2007): 193-215.

New Year’s statement, 1897: Prominent within the collection is Freud’s voluminous correspondence written between 1887 and 1904 to his friend and confidant Wilhelm Fliess, a Berlin physician. The letters reveal how intellectually fruitful this period was, laying out in real time the development of Freud’s theories. This is an English translation of the opening of a letter Freud wrote Fliess on Jan. 3, 1897. In the original letter, Freud expressed his optimism for the coming year, declaring “No New Year has ever found both of us as rich and as ripe.” Indeed, on Sept. 21, 1897, Freud announced to Fliess, “the great secret that has been slowly dawning on me in the last few months.” He had abandoned his seduction theory that all neuroses are the result of sexual abuse in childhood.

Postcard to Martha Freud from New York, 1909: This postcard of the Statue of Liberty is found among Freud’s

[image error]

Postcard to Martha Freud from New York, 1909. Manuscript Division.

“Reisebriefe” or travel letters. It was sent by Freud to his wife Martha on his only trip to the United States, where he delivered a series of lectures on psychoanalysis at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, in September 1909. The postcard also bears the signatures of C. G. Jung and Hungarian psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi, who traveled with Freud, and A. A. Brill and his wife Rose Owen Brill, who met them in New York. Freud later wrote in an autobiographical work that the positive reception of his theories received in America convinced him that “psychoanalysis was not a delusion any longer; it had become a valuable part of reality.”

“Kürzeste Chronik” [“Short Chronicle”], 1929-1939: Other parts of the collection record the daily routine of Freud’s life. Between 1929 and 1939, he recorded events in what he called “Kürzeste Chronik” or “Short Chronicle.” In addition to everyday occurrences, he noted the rise of Nazism. In March 1938, the entries grew chilling: March 13: “Anschluss with Germany”; March 14: “Hitler in Vienna”; March 22: “Anna at Gestapo,” referring to his daughter’s arrest and interrogation at Gestapo headquarters. She was released later that day. Freud’s eventual departure from Nazi-controlled Austria and arrival in London in June 1938 are also noted in the chronicle.

And so the Sigmund Freud Papers go online, 65 years after the first Sigmund Freud Archives donation arrived at the Library of Congress. Consistent with the Sigmund Freud Archives’ commitment to collecting and making available for scholarly use Freud’s personal papers is the encouragement its executive directors gave to this digitization project.

January 31, 2017

Stephen King Joins Library in Announcing Applications for the 2017 Literacy Awards

Award-winning author and literacy advocate Stephen King helped the Library of Congress today launch its call for nominations for the 2017 Library of Congress Literacy Awards. The annual awards support organizations working to promote literacy, both in the United States and worldwide, and are made possible through the generosity of David M. Rubenstein, co-founder and co-CEO of The Carlyle Group.

{mediaObjectId:'46EFFDFA8C2E00ECE0538C93F11600EC',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

According to UNESCO, 757 million adults around the world cannot read or write a simple sentence, and 61 million elementary-age children are not in school.

These awards, which were created and initiated by Rubenstein, encourage the continuing development of innovative methods for promoting literacy and the wide dissemination of the most effective practices. They are intended to draw public attention to the importance of literacy and the need to promote literacy and encourage reading.

The Library of Congress Literacy Awards program is administered by the Library’s Center for the Book. The Librarian of Congress will make final selection of the prizewinners with recommendations from literacy experts on an advisory board.

Three prizes will be awarded in 2017:

The David M. Rubenstein Prize ($150,000) is awarded for an outstanding and measurable contribution to increasing literacy levels, to an organization based either inside or outside the United States that has demonstrated exceptional and sustained depth in its commitment to the advancement of literacy.

Last year’s Rubenstein prizewinner: WETA Reading Rockets

The American Prize ($50,000) is awarded for a significant and measurable contribution to increasing literacy levels, or the national awareness of the importance of literacy, to an organization that is based in the United States.

Last year’s American prizewinner: Parent-Child Home Program

The International Prize ($50,000) is awarded for a significant and measurable contribution to increasing literacy levels, to an organization that is based outside the United States.

Last year’s International prizewinner: Libraries Without Borders

The application rules and a downloadable application are available here. Applications must be received no later than midnight on March 31, 2017, Eastern Time.

More information about last year’s winners and other literacy leaders is available at “Library of Congress Literacy Awards.”

January 27, 2017

Pic of the Week: Presidential Inauguration Treasures

Michelle Krowl of the Manuscript Division speaks about collection items during the “Presidential Inauguration Treasures” display. Photo by Shawn Miller.

The Library is highlighting presidential inauguration history in a temporary display on view through Saturday, Feb. 4 in the rooms known as Mahogany Row, LJ-110 to LJ-113, on the first floor of the Thomas Jefferson Building. Presidential treasures like the handwritten speeches of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln are featured along with collections on the lighter side: menus, dance cards and souvenirs. The display also includes newspapers, film clips, a demonstration of online resources and a challenging presidential history quiz.

The first stop for visitors is in room 113, where Lincoln’s famous First Inaugural Address (“We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection …”) is on display, along with the Bible that Lincoln used at his first inauguration and the pearl necklace worn by Mary Todd Lincoln. Also on view is the handwritten inaugural speeches delivered by George Washington and Thomas Jefferson and a letter written by Washington voicing trepidation about becoming president.

In the connecting rooms, visitors will find inaugural souvenirs from incoming presidents’ parties and parades. An early newspaper report on an inauguration will be on view, and Library staff will demonstrate Chronicling America, a website providing access to historic newspapers that is maintained by the Library of Congress. Film clips will portray the speeches and parades and there will be demonstrations of the Library’s presidential inaugurations website. The quiz will challenge visitors’ knowledge of inaugural firsts. Sample question: Who was the first president to ride to his inauguration in an automobile?

This guide to presidential inaugurations offers a wide variety of primary source materials documenting presidential inaugurations, including diaries and letters written by presidents and those who witnessed the inaugurations, handwritten drafts of inaugural addresses, broadsides, inaugural tickets and programs, prints, photographs and sheet music.

January 26, 2017

New Online: The Walt Whitman Papers in the Charles E. Feinberg Collection

(The following was written by Barbara Bair, historian in the Library’s Manuscript Division.)

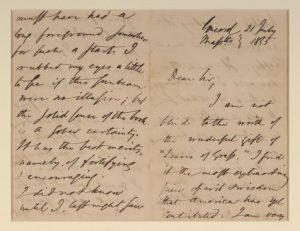

Ralph Waldo Emerson to Walt Whitman, July 21, 1855, on the impact of “Leaves of Grass.” Manuscript Division.

As a special collections repository, the Library of Congress holds the largest collection of Walt Whitman materials anywhere in the world. The Manuscript Division has already made available online the Thomas Biggs Harned Collection of Walt Whitman Papers and the Walt Whitman Papers (Miscellaneous Manuscripts Collection). Now joining these online is the Library’s most extensive collection of Whitman primary documents, the Walt Whitman Papers in the Charles E. Feinberg Collection.

Charles E. Feinberg (1899-1988) was a prominent Whitman collector and Detroit businessman. Through a series of gifts and purchase arrangements, the Library acquired the Feinberg collection of Whitman materials between 1952 and 2010. Rare book editions and related materials from the Feinberg collection are held in the Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division, and many visual images from the Feinberg collection are housed in the Prints and Photographs Division. The Manuscript Division is home to the incomparable Feinberg-Whitman Papers manuscript collection, now newly available to the public, teachers, students, Whitman biographers, poetry lovers and scholarly researchers online.

The Feinberg-Whitman Papers can be accessed electronically through the Library’s Digital Collections portal, or more precisely through folder-level links embedded in the Feinberg-Whitman Papers finding aid created by the Manuscript Division.

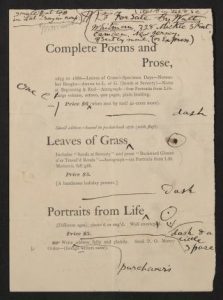

Walt Whitman, edited page proof for advertising circular, “Leaves of Grass” and other publications, c. 1889. Manuscript Division.

The digitized Feinberg-Whitman papers include some 28,000 items in a great variety of primary-document formats, including handwritten notebooks and diaries; scrapbook-like commonplace books; trial lines and draft and edited versions of poems, essays, and speeches; articles and book reviews; annotated maps; original correspondence; and page proofs and other items that document Whitman’s creative process as a writer, poet, newspaperman and book marketer and designer.

The items span from 1763 (prior to the famous poet’s birth in 1819, to a farm family of primarily Dutch heritage on Long Island, N.Y.) to 1985 (through Whitman’s death at his home in Camden, N.J., in March 1892, and extending into Whitman scholarship and publications in the modern era).

Included in the collection are several small artifacts, including a walking stick given to Whitman by his close friend, the naturalist John Burroughs; a haversack that Whitman used when he visited ill and wounded Civil War soldiers in military hospitals in war-time Washington; and a plaster bust created by Sidney H. Morse, as well as a pair of Whitman’s eyeglasses, a pocket watch and a pen.

Walt Whitman’s haversack, c. 1860s. Manuscript Division.

Whitman is known today as one of the nation’s – indeed, the world’s – greatest poets, whose work “Leaves of Grass” (first published in 1855 and published in several revised and expanded editions through the last authorized “death-bed” edition in 1891-92) revolutionized American Literature and spoke for a new democratic age.

Printed program, Charles E. Feinberg address on “Abraham Lincoln and Walt Whitman,” a Lincoln Sesquicentennial event, July 12, 1959, Friends of the Library, University of Detroit. Manuscript Division.

Whitman made a living as a young man in New York as a school teacher, apprentice printer, freelance writer and newspaper editor and writer. He maintained close ties with friends and family and developed strong acquaintances with some of the leading reformers and literary figures of his day. When he lived in Washington, D.C., in the 1860s and 1870s, he continued to write but also made a living as a civil servant, working as a clerk in federal agencies. In the last period of his life, in Camden, N.J., he produced additional prose works and gave a series of public lectures about the death of Abraham Lincoln.

All these periods of Whitman’s life – as well as his legacy and impact on other writers and poets who lived in generations after him – are documented in the Feinberg-Whitman Papers collection.

January 25, 2017

World War I: Restoring Poland

(The following guest post is by Ryan Moore, a cartographic specialist in the Geography and Map Division.)

Prior to World War I, Poland was a memory, and its territory was divided among the empires of Germany, Russia and Austro-Hungary; these powers along with France and Great Britain were wrestling for dominance of the continent, as illustrated in this serio-comic map. The Germans dominated the resource rich lands of Silesia, which were found on the then German eastern border and included cities such as Posen. Germany also controlled the Baltic coastline and the important port city of Danzig. Russia exercised jurisdiction over Warsaw and the eastern regions of historic Poland. Austro-Hungary occupied Galicia. The area contained the culturally important city of Lviv (Lemberg) and mines and oil fields found along the Carpathian Mountains. A 1912 Rand McNally map illustrates Europe without Poland.

[image error]The start of World War I reignited Polish dreams of self-determination. Two years later, in 1916, the Polish cartographer, Eugeniusz Romer (1871-1954), illustrated the rise and fall of his country in this map, pictured left, titled “History.” The map was part of his atlas known as the “Geographical and Statistical Atlas of Poland” that later helped shape Poland’s independence in the Paris peace negotiations of 1919.

Romer produced his atlas in secret, as the authorities of Austro-Hungary, where he lived, reacted harshly to anything that might foment political unrest. Romer combed the archives of the Austrian government, researching census data and economic reports, which he used to craft 32 map plates replete with tables and textual accompaniment in Polish, French and German. His highly detailed depictions included geography, geology, climate, flora, history, political administration, population, ethnography, religious groups, education, land ownership, farming, natural resources and communication networks. The atlas was hailed as masterpiece.

The Germans and Austrians responded swiftly to stamp out this cartographic declaration of independence, and the publication was banned. Romer was forced into hiding to avoid arrest and prosecution. However, copies of the atlas were smuggled to the United Kingdom and the United States and reached policymakers. Upon the American entrance into the war in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson articulated the idea of a free Poland among the goals outlined in his Fourteen Points.

The defeat of Germany and Austro-Hungary, and the collapse of imperial Russia, ended the main barriers to Poland’s independence. Poland’s Prime Minister, the celebrated American concert pianist Ignacy Paderewski, along with Romer and other negotiating team members, believed their territory should stretch as far east as Lithuania and should subsume German-held territory in the west and along the Baltic Sea. To the exasperation of the Americans, British and French, the Poles made seemingly conflicting arguments for territory. In the cases of Silesia and the Baltic coast, they argued that the areas had a majority of Polish speakers and therefore should be Polish. Whereas, in the east, in the case of Galicia and modern-day Lithuania, the argued that historic Polish cultural institutions, such as universities and churches, proved that the land should belong to Poland despite Poles being the minority population.

President Wilson and his team were often sympathetic to the Poles; however, Wilson wanted a “scientific” solution and directed his team to draw borders based on the dominant language of the people in a given area, such as in this map found in the Woodrow Wilson papers. Great Britain, on the other hand, was deeply concerned about this approach. They feared Poland would appropriate too much of Germany’s important natural resources and industry in the east. Britain wanted Germany left in a position to pay restitution for the war and to avoid a communist uprising, like the one in Russia.[image error]

The solution was a compromise that was despised by the Poles and the Germans. The port of Danzig, with its majority German population, was placed under the administration of the League of Nations and placed into a binding customs union with Poland. The port was situated in a narrow strip of Polish territory known as the Polish Corrider. The land was dangerously sandwiched between Germany proper in the west and German East Prussia. Romer illustrated the problem in his map “Administration” (1921), pictured right. Angry about the diplomatic settlement in the west, Poland decided that force of arms was the means necessary to achieve its goals in the east. It mobilized an army and appropriated land that included the city of Vilnius and oil fields in eastern Galicia.

In 1919, the Second Polish Republic was born. The country, however, lacked the population and industrial might of its foreboding German and Russian neighbors. It was forced to count on Great Britain and France to provide military assistance. When the hour of need arrived, however, Poland was largely left to fight alone. In 1939, the Nazis overran Poland in weeks, showing the world a new form of warfare called blitzkrieg (“lighting war”). The Nazi’s occupation lasted until 1944, when the Soviet army drove them back into Germany. The Soviets stayed in Poland until 1989. Today, Poland is a free republic and member of the NATO alliance. Its current borders are illustrated in this Central Intelligence Agency map.

World War I Centennial, 2017-2018: With the most comprehensive collection of multi-format World War I holdings in the nation, the Library of Congress is a unique resource for primary source materials, education plans, public programs and on-site visitor experiences about The Great War including exhibits, symposia and book talks.

January 24, 2017

Campaigning for President

(The following was written by Julie Miller, Barbara Bair and Michelle Krowl, historians in the Library’s Manuscript Division, for the January/February 2017 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

[image error]

Andrew Jackson ticket. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Presidential candidates have used popular culture to promote their campaigns for nearly 200 years.

Today’s political candidates can reach millions of people – on a 24/7 basis – in ways their predecessors could only dream of.

American presidential campaigns from 1789 through the 1820s were different from modern ones in almost every way. Presidential candidates thought it was undignified to campaign. Political parties were embryonic and in flux – nothing like the organizational powerhouses they are today. Before the election of Andrew Jackson in 1828 there was no mass electorate. In most states, legislatures, not citizens, chose presidential electors. Enslaved people, free women, and free propertyless men – constituting most of the adult population at the time – were denied the vote.

Throughout this period, however, both an electorate and campaign machinery began to develop. As Americans moved west and into cities, states began to drop their property requirements for voting. Citizens gradually replaced state legislatures as voters in presidential elections. Political parties evolved from informal “factions” into effective organizations. By the early 1830s, cheap newspapers, known as the “penny press,” allied themselves with political parties, and a growing network of roads, canals and railroads began to carry political information nationwide.

By the Jacksonian era and the elections immediately following, presidential candidates still let their surrogates do most of their campaigning for them. As the franchise continued to expand to include more working-class and propertyless male voters, campaigns involved greater popular participation. The presidential election process was also increasingly competitive and campaign posters began to appear.

In the 1836 presidential election, the Whig Party chose former military commander William Henry Harrison of Ohio to challenge Democrat Martin Van Buren, the incumbent vice president. A past New York governor, senator and secretary of state, Van Buren was a consummate politician. It was during the 1836 campaign that the donkey –that faithful beast of burden who could also be an ornery, strong-willed opponent – emerged as the symbol of the Democratic Party. In his 1870s illustrations, political cartoonist Thomas Nast would associate the elephant with the Republican Party, which succeeded the Whig Party.

[image error]

William Henry Harrison and John Tyler emblem from the 1840 presidential campaign. Prints and Photographs Division.

The presidential campaign of 1840 is often called the first “modern” grassroots campaign. It was also one that further solidified the two-party system of the time – Whigs and Democrats. The campaign was a rematch between Harrison and Van Buren. This time Harrison prevailed. The son of an aristocratic Virginia family, Harrison was nonetheless depicted as a western folk hero. That image was in keeping with the party’s theme of “Log Cabin and Hard Cider Democracy” and Harrison’s frontier status as the first governor of Indiana territory.

Harrison gained fame at the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe, part of a military campaign to suppress a confederation of Indians loyal to the Shawnee leaders Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh. With southerner John Tyler of Virginia as Harrison’s vice presidential running mate, one of the most famous campaign slogans of all time emerged: “Tippecanoe and Tyler, Too.” Campaign souvenirs of all types proliferated, as did commercial products such as Tippecanoe Tobacco and Tippecanoe Soap. Political hype was high and campaigns became popular entertainment. The campaign song emerged, pairing political lyrics with popular tunes.

[image error]

An Abraham Lincoln cigar box label. Manuscript Division.

By the election of 1860, parades, banners and music were part of the political landscape, as were newspapers that openly supported political parties. Advances in printing technology by the mid-19th century allowed Americans to express their political sympathies through their choice of cigars and stationery. Cigar box labels in 1860 included images of Republican presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln and his democratic opponent, Stephen A. Douglas. For those who might have heard of “Honest Old Abe” and the “Little Giant” but had never seen their likenesses in print, the cigar box label introduced the candidates’ faces to the public.

Political buttons touting presidential candidates increased in popularity during the 19th century. Metal campaign buttons were available in 1860, but the election of 1896 saw the first use of the mass-produced, pin-backed, metal buttons. These became ubiquitous and collectible in 20th-century presidential campaigns and remain so today.

The electorate continued to expand. In 1870, the 15th Amendment granted the right to vote to male citizens “regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” The passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920 gave women nationwide the right to vote. The first election in which all American women could vote was a match between two Ohioans – Democratic Governor James M. Cox and Republican Sen. Warren G. Harding, who prevailed. Campaigns reached out to the ladies, reminding them to do their civic duty and vote.

The advent of film and radio in the early 20th century, followed by television in the early 1950s, provided even larger audiences for political campaigns. Dwight D. Eisenhower’s 1952 campaign for president was the first to run a television advertisement. The black-and-white ad featured cartoon characters singing “I like Ike, You like Ike, Everybody likes Ike for President.”

A decade later, television ads would become more dramatic, with Lyndon Johnson’s “Daisy Girl” ad against Barry Goldwater. Created by media consultant Tony Schwartz, whose collection is housed at the Library, the ad featured a child counting daisy petals, followed by a countdown to a nuclear explosion. “ These are the stakes,” warned Johnson. The spot only ran once but remains one of the most memorable in the annals of campaign ads. Negative ads continue to be a mainstay of political campaigns today.

[image error]

Bumper sticker for the Barry Goldwater presidential campaign. Manuscript Division.

In the post-war era, Americans took to the new interstates in their cars and soon bumper stickers proliferated. Later in the 20th century, personalized or “vanity” license plates began promoting candidates.

As it had a century earlier, technological development at the turn of the 21st century – namely the internet – ushered in a new model of political campaigning. The web also allows the Library a new means of documenting modern campaigns. Since 2000, the Library has archived websites related to the U.S. presidential, congressional and gubernatorial elections.

Al Gore, the 2000 Democratic presidential candidate, was a big proponent of the “information superhighway,” but Barack Obama was the first presidential candidate to harness the power of social media. His use of social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook began in early 2007. On the eve of the 2008 election, Obama had more than 1 million “friends” on Facebook – significantly more than his opponent, John McCain. By the 2012 presidential campaign, both Obama and his Republican opponent, Mitt Romney, were actively campaigning on social media.

Use of Twitter by both candidates in the 2016 presidential election was unprecedented. Both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton tweeted into the wee hours of the morning, delivering their messages directly to the voters, and reaching them in record numbers. The 2017 inauguration promises to set new records for all of today’s social media platforms.

January 23, 2017

New Online: The George Washington Papers Move to a New Digital Platform

(The following post is written by Julie Miller, early American historian in the Manuscript Division.)

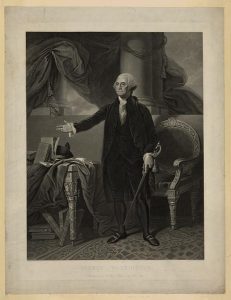

George Washington, painted by G. Stuart; engraved by H.S. Sadd, N.Y. 1844. Prints and Photographs Division.

George Washington was not only the first president of the United States, he was also the first digital president. In 1998 the Library of Congress’s monumental collection of George Washington papers was opened to the world online. The digital Washington papers were part of American Memory, the Library’s first project to digitize its holdings. Begun in 1990 at the dawn of the Internet age, by the year 2000, American Memory had made more than 5 million items available to the public online. Among them were the approximately 77,000 items that constitute the George Washington papers. Now this early foray into cyberspace is being retired and replaced by a new digital platform. The George Washington papers were recently relaunched there.

If you are one of the many scholars, teachers, students and members of the curious public who have relied on the George Washington papers on the American Memory site, don’t worry. All of Washington’s papers are still online. You will, however, see changes in the way the site works. Among the most significant of these changes are the methods you can use to search for items and display your results.

There are multiple ways to search. One is to enter text into the search box that appears at the top of the collection’s landing page. Documents can be found by entering their dates, titles, or, in the case of letters, the names of Washington’s correspondents. Since transcriptions accompany some of these documents (see the landing page for an explanation of what transcriptions are available on the site), it is possible to find some documents with a full-text search.

Another search method, replacing the browse function on American Memory, is to scroll down the landing page and click on the links to the collection’s series. Series are logical groupings that follow the original order of a collection of papers. The George Washington papers have series for diaries, correspondence, financial papers and more.

The collection’s finding aid, or guide, provides a third way to search. There is a link to the finding aid and to other useful tools in the Expert Resources box on the left side of the landing page and on each search results page. Click on the finding aid’s Contents List and you will see series-level links that will take you to images of the papers. Additional links are in the works.

Once you have your list of results, you can limit, order and display it in a variety of ways. The view function allows you to display results in a list, or in gallery, grid or slideshow views. Multipage letters can also be displayed in this range of views or as single images. All these images can be zoomed, and single images can be rotated. While the slideshow view simulates the experience of looking at a reel of microfilm, the single image view allows you to choose pages to view from a box labeled Image.

Search results can be downloaded as GIF’s and JPEGS. When transcriptions are available they can be presented side-by-side with the original text. When transcriptions are not available on the site, viewers have the option of using Founders Online, which includes a digital version of the modern published edition of Washington’s papers. A link to it is available in the Expert Resources Box. Because Founders Online is full-text searchable, it can help you to find dates, correspondents and other information that will allow you to do more accurate searches on the Library of Congress Washington papers site.

Even with these enhancements, the George Washington papers, which layer the 21st century on top of the writing conventions of the 18th, can be confusing to use. To help you we have updated and augmented the explanatory essays that appeared in the browse function of American Memory and renamed them Series Notes. These explain the twists and turns of the more complex series. The note for Series 5, which contains Washington’s financial papers, has been updated, and one for Series 2, Washington’s letterbooks, has been added. The Series Notes can be found under the heading Articles and Essays, where you will find more to help you navigate the collection.

The diaries of George Washington. Manuscript Division.

Maybe you have never looked at Washington’s papers online and are wondering what they have to offer you. The short answer is that they bring George Washington, who we tend to think of as stony and remote, to warm and complicated life. Also, and more unexpectedly, the papers contain documentation of the many lives that intersected with his: fellow military officers and government officials, family members, servants, slaves, neighbors, tradespeople, even the dentists who helped him with his famously failing teeth. By digitizing Washington’s papers, and with this recent digital update, the Library of Congress has made Washington’s papers accessible to everyone, everywhere, anytime.

Who might you meet when you go through this portal to the past? A teenaged George Washington writing in his diary about a surveying trip “over the Mountains” in 1747, or the young aide-de-camp to British general Edward Braddock during the French and Indian War carefully copying his correspondence into a letterbook. Washington later returned to this letterbook and corrected the writing of his younger self. After his marriage in January 1759 to the widowed Martha Custis, the new Mrs. Washington appears in her husband’s ledger books purchasing goods from London suppliers, among them a “coach & 6 in a box,” a toy for her children.

Washington’s commission as commander of the Continental Army, issued to him by the Continental Congress in June 1775 at the start of the Revolutionary War is in the collection. So is a June 17, 1778, report containing this modest admission by the Marquis de Lafayette in response to Washington’s request for military advice from a group of officers: “I am almost the yungest of the general officers who knows less the country I rather refer to theyr Sentiments” the 20-year-old wrote in his uncertain English.

The start of Washington’s presidency is documented by the inaugural speech he delivered at Federal Hall in New York on April 30, 1789. The papers from the era of his presidency also contain a small, paper-bound book that records the Washingtons’ daily expenses during 1793-1794 when the capital was in Philadelphia. This modest volume contains the raw material to construct multitudes of stories about life in 18th-century Philadelphia. The purchases it records include books Martha Washington bought for herself (here a “Ladies Geography” and Mary Wollstonecraft’s 1787 “Thoughts on the Education of Daughters”), a gift of “gold ear drops” the president bought for Martha Washington’s granddaughter, Eleanor Custis; shoes and stockings for Ona Judge and Molly, two of the slaves that served the Washingtons in Philadelphia; and wages for their servants.

The correspondence dating from Washington’s presidency shows him mediating between his feuding cabinet secretaries, Thomas Jefferson, secretary of state, and Alexander Hamilton, secretary of the treasury. On August 23, 1792, fed up, he wrote Jefferson chidingly: “How unfortunate, and how much is it to be regretted then, that whilst we are encompassed on all sides with avowed enemies & insidious friends, that internal dissentions should be harrowing & tearing our vitals.”

Washington found relief from stresses like these by staying in close touch with the manager of his farm at Mount Vernon, who sent him weekly reports. These not only kept him up to date, they also indulged his lifelong passion for agricultural innovation. This passion is equally apparent in Washington’s collection of books on agriculture. His papers document his purchases of these books and preserve the notes he took as he read such works as “The Practical Farmer,” by John Spurrier (1793) and “A Practical Treatise of Husbandry,” by Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau (1759).

The farm reports are also one of the windows that Washington’s papers open onto the lives of the people who worked for him in bondage – slaves. One of these (August 22, 1789) from the summer after he became president, shows men, women, and children hard at work hoeing, harrowing, plowing, weeding, threshing, hauling, stacking, and loading Washington’s wheat, oats, tobacco and vegetables. Slavery, the tragic, unresolvable paradox of American history, is present in Washington’s papers just as it was in his life.

Washington’s papers have long been an inspiration for the hundreds of thousands of people who have used them over the years. We hope that this updated website will make them even more accessible.

January 18, 2017

President for a Day

David Rice Atchison. Photo by Mathew Brady, between 1844-1860. Prints and Photographs Division.

All eyes turn to Washington this week, as the nation’s 45th president is inaugurated on January 20. However, until the passage of the 20th Amendment in 1933, inauguration day was always March 4 in order to allow enough time after Election Day for officials to gather election returns and for newly elected candidates to travel to the capital. With modern advances in communication and transportation, the lengthy transition period proved unnecessary and legislators pressed for change.

In 1849, March 4 fell on a Sunday, and incoming president Zachary Taylor moved the ceremony to the following day. This was the second instance of the inauguration being rescheduled because of observing Sunday as the Sabbath – the first being in 1821 and the reelection of James Monroe.

Precedent had already been set in 1821 with Monroe officially taking up his duties one day after his term constitutionally began. Yet, 25 years later, Taylor’s start was a point of contention. Some historians have argued that Sen. David Rice Atchison, a Democrat from Missouri, was president during those intervening hours. He was of the Senate, and according to the 1792 law in effect at the time, the Senate’s president pro tempore was directly behind the vice president in the line of succession.

Today, most historians and constitutional scholars dispute that claim. At the time, his first term as senator was finished, and he hadn’t yet been sworn in for his second term. So, he didn’t exercise any power.

Atchison spoke with the Plattsburgh Lever in 1792 that he “made no pretense to the office.”

[image error]

The inauguration of Gen. Zachary Taylor. 1849. Prints and Photographs Division.

John Wilson Townsend, writing for the Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society would have you believe otherwise. In an article from the May 1910 issue of the register, Townsend cited a story that appeared in the Philadelphia Press that had been “rather thoroughly circulated and has actually been accepted by several otherwise reliable biographical dictionaries.”

Stated the article, “That Senator Atchison considered himself President there was no doubt, for on Monday morning, when the Senate reassembled he sent to the White House for the seal of the great office and signed one or two official papers as President. These were some small acts in connection with the inauguration that had been neglected by President Polk.”

While Atchison may or may not have been “president for a day,” by right of succession, he was vice president from April 18, 1853, until December 4, 1854, when President Franklin Pierce’s vice president, William R. King, died.

The Library has numerous collections and presentations related to U.S. elections, presidents, politics and government, including this great resource guide on presidential elections from 1789-1920 that includes resources on the 1848 election.

Also, you can check out all the Library’s digital collections on government, law and politics, which include the papers of Zachary Taylor.

Sources: history.com

January 17, 2017

Trending: The Inauguration Will Not (Just) Be Televised

(The following post is featured in the January/February 2017 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, and was written by Audrey Fischer, LCM editor. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

The inauguration of the 45th president will be the social media event of the year.

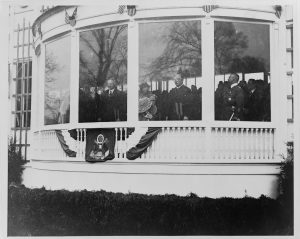

Calvin Coolidge speaks at his inauguration on March 4, 1925, National Photo Company Collection, Prints and Photographs Division.

Today, social media provides an unlimited opportunity for individuals and media outlets to record and be a witness to such historical events as the presidential inauguration. These sounds and images are then instantaneously shared through computers and mobile devices with a global audience.

This is, of course, a relatively new development.

For the nation’s first 100 years, people got their news by word of mouth and from the printed page. Newspaper accounts of presidential inaugurations – with images largely engraved – informed the public. A number of prolific diarists provided first-person accounts for those unable, or uninvited, to attend the festivities in the nation’s capital. Those who received telegrams or glimpsed the first photographic image of the event – James Buchanan’s 1857 inaugural – must have felt that the modern age had truly arrived.

William McKinley’s March 4, 1897, inauguration was the first to be recorded by a movie camera. The 2-minute film footage shows the inaugural procession down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. Film footage from McKinley’s second inauguration in 1901 shows the president addressing crowds on Pennsylvania Avenue, riding in a processional to the Capitol and taking the oath of office. The short clips, produced by Thomas Edison, came to the Library through the copyright registration process and are part of the Library’s Paper Print Collection. Discovered in 1942, the paper copies were converted into projectable celluloid images.

McKinley was shot by an assailant while attending the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, on Sept. 6, 1901, and died a week later from complications. The Library holds film footage of McKinley’s day at the exposition and scenes from his funeral in Canton, Ohio.

Herbert Hoover, Mrs. Hoover and William Howard Taft watch the inaugural parade on March 4, 1929, National Photo Company Collection, Prints

and Photographs Division.

Calvin Coolidge’s inauguration in 1925 was the first to be broadcast nationally on radio. The address delivered by the man known as “Silent Cal” could be heard by more than 25 million Americans, according to a New York Times report, making it an unprecedented national event.

Herbert Hoover’s inauguration in 1929 was the first to be recorded by a sound newsreel. It marked the second and last time that a former president, William Howard Taft, administered the presidential oath.

Harry S. Truman’s inauguration in January 1949 was the first to be televised, though few Americans owned their own set. In 1981, Ronald Reagan’s inauguration was broadcast on television with closed captioning for the hearing-impaired. During Reagan’s second inauguration in 1985, a television camera was placed inside his limousine – another first – to capture his trip from the Capitol to the White House.

Barack Obama takes the oath of of ce on Jan. 20, 2009. Susan Walsh, Associated Press Photo/Corbis.

Bill Clinton’s 1997 second inauguration was the first to be broadcast live on the Internet. President Clinton had signed the Telecommunications Act of 1996 at the Library of Congress the previous year.

Barack Obama’s historic first inauguration on Jan. 20, 2009, garnered the highest Internet audience for a presidential swearing-in. It was the first inaugural webcast to include captioning for the hearing-impaired. According to the Wall Street Journal, President Obama’s second inauguration generated 1.1 million tweets – up from 82,000 at the 2009 event.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers