Library of Congress's Blog, page 122

November 23, 2016

World War I: “Trench Blues” — An African American Song of the War

(The following is a guest post written by Stephanie Hall of the American Folklife Center.)

[image error]

John Bray, Amelia, Louisiana. Photo by Alan Lomax, 1934. Prints and Photographs Division.

In 1934, folklorist John Lomax and his 19-year-old son Alan went to southern Louisiana to collect folksongs and music in many styles from several ethnic groups in English and French. Among the songs in the resulting collection is “Trench Blues,” a World War I song composed and sung by John Bray in Ameila, St. Mary’s Parish, Louisiana. “Trench Blues” is important as a statement from one African American about the experience of going to war. Not many songs airing strong personal statements about the First World War by African Americans survive today.

We are lucky that the Lomaxes recorded this song, given that it doesn’t fit many definitions of “folk music.” John Lomax used one such definition to guide his work: the older songs and tunes of a community, which have no known author. Therefore, he did not have a strong interest in recording contemporary music like this song. Luckily, Alan’s interests were broader than his father’s; he recorded this particular song and apparently corrected its catalog card to make that fact clear.

During World War I, African Americans mainly did work in support of the combat troops, with a smaller number trained for combat. According to the Lomaxes, Bray did not serve in a combat unit. It seems likely that the Army would have valued Bray’s work skills. We learn a little about those skills in another song he sang for the Lomaxes, “Cypress Logging Holler,” which he used to coordinate workers moving logs from Louisiana swamps to the saw mill – a difficult job. According to his draft registration he was working as a pond man for the Ramos Lumber Company, famous for their cypress lumber, when he was drafted in 1917.

{mediaObjectId:'34CAC1D71D1701B2E0538C93F11601B2',metadata:["

Audio provided by Library of Congress"],mediaType:'A',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

“Cypress LoggingHoller,” sung by John Bray, Louisiana, 1934. American Folklife Center

African American soldiers were segregated and often looked down on and even mistreated by white servicemen. The Army allowed African Americans to become officers, as they thought that it was better for the African American units to be commanded by their own officers. But these soldiers were not treated as equal to others of similar rank. When African American veterans returned home, there was often no fanfare. They were not regarded as heroes except in their own communities and often felt forgotten or neglected by the nation they had gone to war for. There had been great hope among African Americans that service in the war would make a big difference in how they were seen as Americans. Instead, it became a galvanizing moment that led to later efforts to gain equality.

[image error]

John Bray’s draft registration for World War I. National Archives and Records Administration.

“Trench Blues” is John Bray’s story about going to war in 1917 at 28. He tells of his experiences aboard ship while worrying about German submarines below the waves. He then describes how it felt in his “home in the trenches, living in a big dugout,” of being among “40,000 soldiers called out to drill” and going to Belgium. Listeners should be aware that he uses a pejorative word for African Americans in the song. The line explains that “We went to Berlin, went with all our will and if the white soldiers don’t get him, the [African Americans] certainly will.” It is a moment in the song when Bray takes the opportunity to comment on being regarded as inferior and to say that this was not the case, all in a short verse. The verse may also imply that the non-combat African Americans providing support to the combat troops would nevertheless stop any of the enemy from escaping.

{mediaObjectId:'34CAC1DAD7780032E0538C93F1160032',metadata:["

Audio provided by Library of Congress"],mediaType:'A',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

“Trench Blues,” composed and sung by John Bray, Louisiana, 1934. American Folklife Center.

Segregated military units and the idea that most African Americans were better suited to labor than combat set them at a lower social level within the Army. By using this insulting word to mean something positive, John Bray is taking the power back, which was not unusual in the blues of the time. You will also hear that Bray uses a nickname derived from this insult, probably given to him at lumber camps. I take this to be another way of showing that the word has no power over him.

[image error]

John Bray pretending to hold up a bridge, Amelia, Louisiana. Photo by Alan Lomax, 1934. Prints and Photographs Division.

We do not have much biographical information on John Bray to see how the song reflects the details of his service. But what we have is a song with the ring of emotional truth. He sings of his fears, other soldiers’ fears and the reactions of civilians. He tells of the many soldiers who lost their lives and of the triumph of victory. Above all, he asserts the importance of the African American soldiers – as important as any other Americans who risked their lives for their country during World War I.

The John A. Lomax southern states collection, 1933-1937 includes these recordings made with John Lomax in 1934. Joshua Caffery, 2013 John W. Kluge Center Alan Lomax Fellow, made the 1934 recordings available online as part of his work.

The Library of Congress has enjoyed a long association with the Lomax family, beginning in 1933 with John A. Lomax’s appointment as Honorary Consultant and Curator of the Archive of American Folk-Song, and his son Alan’s appointment as “Assistant-in-Charge” of the archive in 1937. During their time at the Library, which ended in late 1942, the duo made long trips through the United States and the Caribbean, documenting American culture in its diverse manifestations. Alan’s dynamic career from the 1940s to the 1990s generated a large archive that the Library acquired after his death in 2002. The children of Bess Lomax Hawes, Alan’s equally accomplished sister, donated her materials to the center in 2014.

World War I Centennial, 2017-2018: With the most comprehensive collection of multi-format World War I holdings in the nation, the Library of Congress is a unique resource for primary source materials,education plans, public programs and on-site visitor experiences about The Great War including exhibits, symposia and book talks.

November 22, 2016

The Power of Photography

(The following is a feature story from the November/December 2016 Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, that was written by Helena Zinkham, director of the Library’s Collections and Services Directorate and chief of the Prints and Photographs Division. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

[image error]

Photographs like this one of Marilyn Monroe taken by John Vachon for Look Magazine inspired a 2010 book.

What do Marilyn Monroe, Civil War soldiers and the Wright Brothers have in common? Books about these subjects all feature photographs found at the Library of Congress.

Over more than 150 years, the Library has built an internationally significant photography collection. From the dawn of photography to today’s cell phone cameras, images in the Library’s photograph collections help historians, students and teachers, curators, journalists, novelists and filmmakers—to name a few—understand the past and tell fascinating stories.

The most frequent use of the Library’s more than 14 million photographs is to illustrate publications, which have expanded to include social media and websites. And with more than 1 million of these images available on the Library’s website, the images can be accessed around the globe.

Icons like Marilyn Monroe, Jacqueline and John F. Kennedy have remained popular subjects for articles, documentaries and full-length biographies, long after their deaths. They are well-represented in the more than 4 million images that comprise the Look Magazine Photograph Collection in the Library of Congress. Covering the magazine’s publishing cycle, 1937-1971, the published and unpublished photographs depict life in America over four decades.

[image error]

This Civil War era photograph of an African American Union soldier with his wife and daughters is one of many that inspired a recent exhibition at the California African American Museum.

Historian Jack Larkin mined the Library’s collection for images of farmers, mill girls, housemaids, gold miners, railway porters, cowboys, newsboys and stenographers to illustrate his book, “Where We Worked: A Celebration of America’s Workers and the Nation They Built.”

“I would also like to thank my unsung heroes—the visual archivists and imaging specialists at the Library of Congress,” said Larkin in the book’s acknowledgements. “They have created an extraordinary online collection, making available our nation’s greatest single resource for the visual study of the American past.”

Novelists are also inspired by photographs. The striking face of Addie Card stimulated author Elizabeth Winthrop to write “Counting on Grace”—a fictional children’s story about a girl who worked in a textile mill in Vermont at the turn of the last century. The image is one many photographed by Lewis Hine for the U.S. National Child Labor Committee—the records and photographs of which are housed in the Library of Congress. To gather background information, Winthrop hired genealogist and journalist Joe Manning to track down what happened to Card later in life. Manning became so curious about the other child laborers photographed by Hine that he launched a website, called Mornings on Maple Street, where his extensive research now chronicles the lives of more than 150 child laborers, including interviews with their descendants. “Counting on Grace” is also used in the classrooms to teach about the plight of working children.

Always a popular research topic, the Civil War continued to garner interest during its recent sesquicentennial (2011-2015). In the past six years since the Library acquired and displayed the Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War photographs, more than 30 books—and many more magazines and online resources—brought the era to life with these vivid images. In 2013, the California African American Museum honored the estimated 180,000 black soldiers who fought in the Civil War by reproducing and displaying life-size portraits from the Liljenquist Collection. For the show’s signature image, the curator selected the rare glimpse of a Union soldier posed with his wife and two daughters.

[image error]

The Library’s online Civil War photographs, like this one of President Abraham Lincoln and General McClellan on Antietam battlefield, were used to create the sets for filmmaker Salvador Litvak’s 2013 film, “Saving Lincoln.”

Documentary filmmaker Salvador Litvak was motivated to develop a new cinematic technique—CineCollage—while reviewing the Library’s digitized Civil War photographs online. Litvak created the sets for his 2013 film “Saving Lincoln” by filming 3D composites from the digital images. He captured the actors’ performances on a green screen, which allowed him to place them in front of the historic background. Litvak said his “a-ha!” moment occurred late at night while sleuthing through the Library’s online photographs.

“I stared at a high resolution image of a glass plate negative created in 1865. The photograph depicted wounded Union soldiers in an Army hospital. I zoomed deep into the picture and focused on an emaciated young soldier sitting at the back of the room. His eyes pierced mine, and I wondered how he would react to a visit by President Lincoln.”

To celebrate the centennial of manned, powered flight in 2003, several aviation groups attempted accurate reconstructions of the 1903 Wright Brothers airplane that were capable of flying. Their work was informed by mechanical details visible in photographs housed in the Library of Congress that were not documented in the written records.

Historian David McCullough—and many other authors—have drawn on the Wright Brothers Papers and photographs in the Library’s collections to write biographies of the pioneer aviators. McCullough, whose latest book “The Wright Brothers” features a photo of pioneering plane on its cover, credits the Library’s photograph collections with launching his career.

“After seeing pictures of the 1889 flood in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, in the Library’s Prints and Photographs Collection, I began writing my first history, ‘The Johnstown Flood’ (1968).”

The ability to digitize and make its collections available online has allowed the Library to provide access to these valuable resources in the classroom. The Library’s Teachers Page helps educators engage their students in the curriculum through the Library’s primary sources and photographs. The site offers primary source sets on topics ranging from America in wartime to America’s favorite pastime—baseball.

The Library is also sharing its baseball collections with new audiences at Nationals Park in Washington, D.C. In collaboration with the Washington Nationals, “Baseball Americana from the Library of Congress” opened at Nationals Park in April 2015 and remains on view.

[image error]

Baseball Americana display at Nationals Park. Courtesy The Washington Nationals.

The popular photo-sharing site Flickr also allows the Library to reach new and diverse audiences through its photographs. The site has enriched the Library’s photograph collections by opening a dialogue with end users who have “tagged” or commented on the images. Since 2008 when the Flickr Commons project started, the Library has received identifying information for many thousands of photographs. Users have also submitted their own photographs to show how historic sites look today, and many have expressed their appreciation for the rich images mounted on the site by the Library. The Library’s most popular collection on Flickr remains the color photography from the Great Depression and World War II.

The Library of Congress invites you to join the conversation on its Flickr and Instagram sites. View the national picture collection any time—online or in-person at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.—to find a piece of your family history, a new understanding of the past or fresh inspiration for your own creative endeavors.

November 18, 2016

Pic of the Week: Smokey Robinson

Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden interviews Gershwin Prize for Popular Song recipient Smokey Robinson at the Gershwin piano, November 15, 2016. Photo by Shawn Miller.

The two-day celebration of Smokey Robinson’s 50-year career—and his selection as the 2016 recipient of the Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song—began in the nation’s capital with a touching trip down the keyboard of George Gershwin’s piano and ended with a rollicking concert of his greatest hits.

During his visit, Robinson sat down at the Gershwin piano, housed in the Library’s ongoing exhibit, “Here to Stay: The Legacy of George and Ira Gershwin,” and talked about his work and the Gershwin legacy. “The Gershwins wrote music when the song was king,” the Grammy Award-winner told Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden. “For me to even be mentioned in the same breath with the Gershwins as a songwriter is just incredible.” Robinson tearfully recalled how Gordy mentored him and helped him achieve his dream of becoming a singer and songwriter.

Then, actor Samuel L. Jackson hosted an all-star tribute concert at DAR Constitution Hall featuring Aloe Blacc, Gallant, Berry Gordy, CeeLo Green, JoJo, Ledisi, Tegan Marie, Kip Moore, Corinne Bailey Rae, Esperanza Spalding, the Tenors and BeBe Winans. The honoree also performed some of his favorite tunes. The concert will air on PBS stations nationwide at 9 p.m. ET on Friday, Feb. 10 (check local listings).

During the evening’s event, Robinson will be presented with the prize by Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden, U. S. House of Representatives Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy, U.S. House of Representatives Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi, U.S. Senate Democratic Whip Richard J. Durbin, U.S. House of Representatives Democratic Whip Steny H. Hoyer, U.S. House of Representatives Chairman of the Committee on House Administration Candice S. Miller and U.S. House of Representatives Vice Chairman of the Joint Committee on the Library of Congress Gregg Harper.

Congressional leaders join Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden in presenting Smokey Robinson with the 2016 Gershwin Prize for Popular Song during a tribute concert at DAR Constitution Hall, November 16, 2016. Photo by Shawn Miller.

November 17, 2016

What Time Is It?

Standard time zones of the world, January 2015. Geography and Map Division.

With the recent “fall back” of daylight saving time, we had to reset our clocks and maybe our brains to get used to the change. And, if you’re someone that conducts business in different time zones, that adjustment can take additional getting used to. I know I always have trouble remembering how far ahead or behind other places are in reference to my location, despite having essentially lived at one time or another in all four time zones.

The idea of time zones was actually introduced on Nov. 18, 1883, by North American railroads in an effort to better coordinate train schedules. Standard Railway Time ushered in ordinances enacted by many American cities, which then gave rise to the creation of time “zones.”

[image error]

The Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith, June 1, 2015. Prints and Photographs Division.

Before clocks, people marked time by the sun and the phases of the moon. With the development of the railway and the invention of the telegraph, accurate time became more important. Prior to adopting SRT, trains traveling east or west between towns had a difficult time maintaining coherent schedules and smooth operations.

The four standard time zones quickly adopted nationwide were Eastern Standard Time, Central daylight Time, Mountain Standard Time and Pacific Daylight Time. They were each one-hour wide due to the fact that 15 degrees of longitude corresponds to a one-hour difference in solar time.

[image error]

Burlington Route. 1892. Geography and Map Division.

While time zones may have been established with the railroads, the idea of standardized time had been discussed long before. In 1875, Cleveland Abbe – astronomer, meteorologist, and the first head of the U.S. Weather Bureau – lobbied the American Meteorological Society (AMS) to take action on a uniform standard time. You can read more about the history of times zones in this Today in History entry.

As one can imagine, there was some confusion, due to the border of the time zones running through major cities. For example, the border between its Eastern and Central time zones ran through Detroit, Buffalo, Pittsburgh, Atlanta and Charleston. However, Detroit kept local time until 1900, then tried Central Standard Time, local mean time and Eastern Standard Time. The confusion of times came to an end when Standard zone time was formally adopted by the U.S. Congress in the Standard Time Act of March 19, 1918.

Sources: Daylight Saving Time

November 14, 2016

Gwen Ifill, a History-Tracker and a HistoryMaker

Gwen Ifill. Photo by Robert Severi

Those who appreciate high-quality broadcast news were saddened today to learn of the passing of longtime PBS NewsHour co-host and Washington Week moderator Gwen Ifill.

The former New York Times, Washington Post and NBC News political, congressional and White House reporter, 61, had been under treatment for cancer. She and her NewsHour co-host Judy Woodruff were the first women to co-anchor a U.S. nightly newscast. She also wrote for the Baltimore Sun and the Boston Herald-American. In the course of her career she won a George Foster Peabody Award (honoring distinguished and meritorious work in radio and television), the Leonard Zeidenberg First Amendment Award of the Radio/Television Digital News Association and the National Press Club’s highest honor, the Fourth Estate Award, among many other honors. Ebony Magazine listed her among the nation’s 150 most influential African Americans. She also served on the board of directors of the American Archive of Public Broadcasting, a joint project of the Library and WGBH to preserve and provide access to the nation’s public broadcasting heritage. She also served on the board of the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Ifill wrote “The Breakthrough: Politics and Race in the Age of Obama” (2009), which she spoke about at the Library of Congress National Book Festival that year. She was also a moderator of televised political debates, including the 2004 and 2008 vice-presidential debates and a 2016 Democratic primary debate.

She interviewed former U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice John Paul Stevens when he came to the Law Library of Congress to receive the Wickersham Award for exceptional public service from the Friends of the Law Library of Congress.

Gwen Ifill is among the media figures represented in the video history collection known as “The HistoryMakers,” a collection of videos of African American public figures interviewed for the public record. This documentary record was added to the collections of the Library of Congress in 2014. She was interviewed for the collection in 2012.

Ifill was known not only for her consummate professionalism but also as a thoughtful and generous person. In an address delivered at the Library in 2013, she said: “Whose stories can you tell? Whose voices are not being heard? Which stories and voices go unheard, and–most of all–what are you willing to do about it?”

Writing the Great Novel

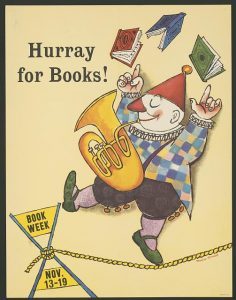

“Hurray for books!,” by Maurice Sendak. 1960. Prints and Photographs Division.

November is National Novel Writing Month. Perhaps you’ve heard of, or even signed up for, the NaNoWriMo movement. Encouraging individuals to write and complete a 50,000-word novel from November 1-30, the nonprofit movement provides support, inspiration and community for budding writers to pick up that pen or open that laptop. To date, more than 9 million people from all over the world have signed up.

The Library’s collections are home to many storied novelists and writers, including Ayn Rand, Vladimir Nabokov, Ralph Ellison, Walt Whitman, John Updike and Zora Neal Hurston. Further, one could argue the Library is a literary salon, of sorts, hosting throughout the year many authors through its Books and Beyond program as well as at the National Book Festival.

While looking through the collections, I discovered that the Library has the papers of Shirley Jackson. I admit I was inspired to write about her not only because of appreciation of her work but also because a former roller derby teammate of mine used to play under the name “Surly Jackson.” While I know she was a popular author during her time, I think she deserves a renewed look in ours.

Jackson (the novelist not the derby player) wrote short stories frequently focused on witchcraft, the occult and abnormal psychology. She is perhaps best known for a macabre story about a community’s yearly ritual of selecting a person to be brutally stoned to death. Drafts of “The Lottery” are among Jackson’s papers, which also contain diaries, letters and files on the vaguely autobiographical works “Life Among the Savages” (1953) and “Raising Demons” (1957), in which she presents a humorous albeit strange account of raising children, cleaning house and cooking meals in a disordered suburban environment.

Jackson’s role as wife, mother and author fit her well, as much of her experiences informed and inspired her writing. Letters in the collection from her trusted friends and associates suggest the deep personal regard they held for Jackson as both a professional writer whose stories were increasingly gaining critical acclaim and popular recognition and as a wife and mother who saw no incompatibility between her dual roles as artist and homemaker.

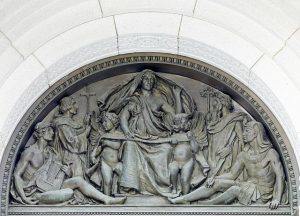

Bronze tympanum representing writing, located above main entrance doors of the Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith, 2007. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Library also has the papers of Jackson’s husband, literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman. He largely took a hands-off approach to rearing the children and participating in domestic life. However, letters in the Shirley Jackson collection between the couple reflect their converging interests and emotional commitment and suggest the passionate elements that would be characteristic of their relationship throughout their lives.

You can read more about the Library’s literature holdings in this illustrated guide to the collections of the Manuscript Division.

And, if you’re looking for a little inspiration in your writing, you may want to use this web guide on how to find specific novels, poems or short stories or check out the Library exhibition “America Reads” Really, though, the Library is a veritable smorgasbord of resources and ideas to help you with your writing. Simply search for terms like “novel,” “novelists” and “fiction.”

Sources: New York Magazine

November 10, 2016

Veterans History Project Gets New “Book”

Featured on VHP’s Facebook page, hero of the new film, “Hacksaw Ridge,” Desmond Doss. Veterans History Project.

Adding another “book” to its social media shelf, the Library of Congress welcomes the Veterans History Project to Facebook. There, VHP will be sharing the stories of our veterans along with other news and initiatives. Visitors are also encouraged to share their own stories and help VHP collect more.

VHP’s Facebook joins several other Facebook accounts from the Library, along with a variety of other social media like Twitter, Pinterest, YouTube, Instagram and iTunesU. You can stay in touch with the Library and learn new ways to use its resources through this collection of social media technologies and bulletin services.

November 9, 2016

World War I: Helen Johns Kirtland, Frontline Photojournalist

(The following is a guest post by Beverly Brannan, curator of photography in the Prints and Photographs Division.

[image error]

Helen Johns Kirtland. ca. 1919. Prints and Photographs Division.

Helen Johns Kirtland must have been a very persuasive person because only a few U.S. women obtained credentials to report in countries actively fighting in World War I. Both she and her husband Lucien Swift Kirtland secured permission to work as war correspondents in Europe in 1917. By policy, husband and wife could not work together; so once in Europe, they went their separate ways and met up only occasionally. As a photojournalist Helen provided photographs for Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly and other American periodicals in Europe. She also photographed and did publicity work for the Red Cross, and the United States Army and Navy provided her opportunities for reportage and photography, as well.

While Kirtland reported on the war elsewhere, the Italian army suffered a major defeat at the hands of the Austrian and German forces between October 24 and November 19, 1917. The Austrians broke through the Italian line at Caporetto on the Piave River, leaving the defending Italians with 10,000 dead, 30,000 wounded, 265,000 captured and 350,000 missing. The Italian military then declared that no women could visit the active front.

During the autumn months of 1918, when the two armies again confronted each other, Kirtland was the only woman correspondent allowed to photograph the encounter. She had persuaded Italian finance minister Francesco Saverio Nitti and Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando to grant her special access to the field.

[image error]

Italian soldiers lighting cigarettes, one holding illustrated newspaper, Piave River, Italy, October 1918. Prints and Photographs Division.

Despite concerted Austrian attacks, the Italian line held at the river this time and decisively defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto at the end of October. Kirtland was on the actual front during the last drive at the battle for Monte Grappa and went with the Army as far as the mouth of the Piave River.

By 1918, Kirtland had a year’s experience reporting on the war and obviously felt comfortable chatting with foot soldiers on battlefields. Her uncaptioned photographs indicate that she continued to cover various fronts, including Belgium and Poland. At war’s end, the Kirtlands worked together to provide extensive coverage of the peace negotiations at Versailles.

[image error]

Winning the war from the clouds. Photographs by Helen Johns Kirtland, staff photographer for Leslie’s. Prints and Photographs Division.

Helen Johns Kirtland became a member of the Society of Woman Geographers, which was established in 1925 for women who had “done distinctive work whereby they have added to the world’s store of knowledge concerning the countries on which they have specialized, and have published in magazines or in book form a record of their work.” At the time, women were excluded from membership in most professional organizations.

Among the more than 4,000 photographs in the Kirtland Collection in the Prints & Photographs Division, some 200 images show World War I and its aftermath, adding a valuable perspective to coverage found in other collections.

World War I Centennial, 2017-2018: With the most comprehensive collection of multi-format World War I holdings in the nation, the Library of Congress is a unique resource for primary source materials, education plans, public programs and on-site visitor experiences about The Great War including exhibits, symposia and book talks.

Source: Ware, Susan. (1988) “Letter to the World: Seven Women Who Shaped the American Century,” by Susan Ware.

World War 1: Helen Johns Kirtland, Frontline Photojournalist

(The following is a guest post by Beverly Brannan, librarian in the Prints and Photographs Division.

[image error]

Helen Johns Kirtland. ca. 1919. Prints and Photographs Division.

Helen Johns Kirtland must have been a very persuasive person because only a few U.S. women obtained credentials to report in countries actively fighting in World War I. Both she and her husband Lucien Swift Kirtland secured permission to work as war correspondents in Europe in 1917. By policy, husband and wife could not work together; so once in Europe, they went their separate ways and met up only occasionally. As a photojournalist Helen provided photographs for Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly and other American periodicals in Europe. She also photographed and did publicity work for the Red Cross, and the United States Army and Navy provided her opportunities for reportage and photography, as well.

While Kirtland reported on the war elsewhere, the Italian army suffered a major defeat at the hands of the Austrian and German forces between October 24 and November 19, 1917. The Austrians broke through the Italian line at Caporetto on the Piave River, leaving the defending Italians with 10,000 dead, 30,000 wounded, 265,000 captured and 350,000 missing. The Italian military then declared that no women could visit the active front.

During the autumn months of 1918, when the two armies again confronted each other, Kirtland was the only woman correspondent allowed to photograph the encounter. She had persuaded Italian finance minister Francesco Saverio Nitti and Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando to grant her special access to the field.

[image error]

Italian soldiers lighting cigarettes, one holding illustrated newspaper, Piave River, Italy, October 1918. Prints and Photographs Division.

Despite concerted Austrian attacks, the Italian line held at the river this time and decisively defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto at the end of October. Kirtland was on the actual front during the last drive at the battle for Monte Grappa and went with the Army as far as the mouth of the Piave River.

By 1918, Kirtland had a year’s experience reporting on the war and obviously felt comfortable chatting with foot soldiers on battlefields. Her uncaptioned photographs indicate that she continued to cover various fronts, including Belgium and Poland. At war’s end, the Kirtlands worked together to provide extensive coverage of the peace negotiations at Versailles.

[image error]

Helen Johns Kirtland seated at table with Italian military officers near the Piave River, Italy, October 1918. Prints and Photographs Division.

Helen Johns Kirtland became a member of the Society of Woman Geographers, which was established in 1925 for women who had “done distinctive work whereby they have added to the world’s store of knowledge concerning the countries on which they have specialized, and have published in magazines or in book form a record of their work.” At the time, women were excluded from membership in most professional organizations.

Among the more than 4,000 photographs in the Kirtland Collection in the Prints & Photographs Division, some 200 images show World War I and its aftermath, adding a valuable perspective to coverage found in other collections.

World War I Centennial, 2017-2018: With the most comprehensive collection of multi-format World War I holdings in the nation, the Library of Congress is a unique resource for primary source materials, education plans, public programs and on-site visitor experiences about The Great War including exhibits, symposia and book talks.

Source: Ware, Susan. (1988) “Letter to the World: Seven Women Who Shaped the American Century,” by Susan Ware.

November 8, 2016

Election Day Collection Coverage

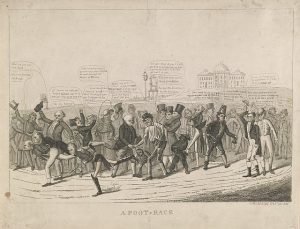

A figurative portrayal of the presidential race of 1824. Prints and Photographs Division.

Today, American citizens gather en masse to exercise their right to vote for the nation’s next president. This particular election will certainly go down in the history books as an interesting one. However, American presidential election history is full of choice moments.

This election year hasn’t been the first to see name-calling and insults. In 1828, a highly contentious rematch between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson saw personal aspersions cast against Jackson’s wife and mother and Jackson being faulted for a murderous past. The 1824 presidential election had ended in confusion. Jackson had actually received a majority in the popular vote but not in the Electoral College. Adams was declared winner by the House of Representatives, and Jackson spent the next four years accusing him of corruption. The 1828 campaign became one of the most bitter in American history.

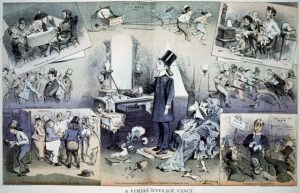

“A female suffrage fancy,” by J. Keppler. July 14, 1880. Prints and Photographs Division.

Hillary Clinton may be the most successful female presidential candidate to date, but she is not the first woman to run for the position. According to Smithsonian, more than 200 women have sought the executive office, with varying degrees of success. Most notably was Victoria Woodhull, the first woman nominated as a presidential candidate. She ran on the Equal Right’s Party ticket in 1872 with Frederick Douglass as the Vice Presidential candidate, running against Republican president Ulysses S. Grant and Democratic candidate Horace Greeley.

She announced her candidacy in the April 2, 1870, issue of the New York Herald. In her column, titled “The Coming Woman,” she laid out her platform that included equality for women, prison reform, a firmer policy on Cuba and an actual policy for paying the national debt.

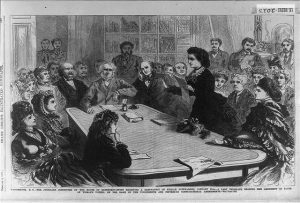

The Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives receiving a deputation of female suffragists. The woman speaking is identified as Victoria Woodhull. 1871. Prints and Photographs Division.

“While others of my sex devoted themselves to a crusade against the laws that shackle the women of the country, I asserted my individual independence; while others prayed for the good time coming, I worked for it; while others argued the equality of woman with man, I proved it by successfully engaging in business: while others sought to show that there was no valid reason why woman should be treated socially and politically as a being inferior to man, I boldly entered the arena of politics and business and exercised the rights I already possessed. I therefore claim the right to speak for the unenfranchised women of the country.”

Woodhull wouldn’t be able to vote for herself, because women were still about 50 years shy of that right. Also, she wouldn’t yet be 35 on Inauguration Day, technically making her ineligible. Ultimately, none of that mattered as Woodhull received zero Electoral College votes, and there is no record of how many popular votes she received, as her name on state ballots was inconsistent.

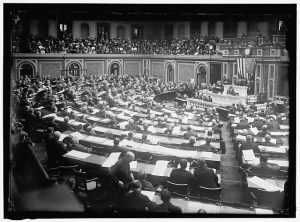

Counting the electoral vote. 1913. Prints and Photographs Division.

Woodhull tried again in 1892 with what was left of the Equal Rights Party, but the attempt wasn’t successful. Read more about her in the Library’s Chronicling America historical newspaper collections.

Fun fact: The Constitution does not state when Election Day should be, only saying that Congress may determine a day electors shall give their votes and that it must be the same across the United States. So that meant in the early 1800s, people could vote from April to December. Can you imagine having to have a recount? In 1845, Congress decided that voting day would be the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November, which was after the fall harvest and before winter conditions made travel too difficult.

The Library has numerous collections and presentations related to U.S. elections, presidents, politics and government, including elections resources for teachers, presidential campaign music and this great resource guide on presidential elections from 1789-1920. Also, you can check out all the Library’s digital collections on government, law and politics here.

Sources: Smithsonian Magazine; U.S. News

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers