Library of Congress's Blog, page 120

January 13, 2017

Pic of the Week: Congressional Kick-Off

The Library of Congress welcomed new members of Congress and their family, friends and supporters at events marking the start of the new term of the 115th Congress last week.

Vice President Joe Biden congratulates new Rep. Lisa Blunt Rochester on Jan. 3. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Five new members of Congress – joined by about 800 guests – held receptions in the Jefferson or Madison buildings: Reps. Anthony Brown (D-Maryland), Tom O’Halleran (D-Arizona), Jamie Raskin (D-Maryland), Lisa Blunt Rochester (D-Delaware) and Lloyd Smucker (R-Pennsylvania). Vice President Joe Biden also made a special appearance to congratulate Blunt Rochester, the newest (and only) member of the House from Delaware – a state Biden represented in the Senate for 36 years. Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden also stopped by some of the festivities to welcome the new members.

Carla Hayden greets Rep. Lloyd Smucker in the Members Room. Photo by Shawn Miller.

January 11, 2017

World War I: Understanding the War at Sea Through Maps

(The following guest post is by Ryan Moore, a cartographic specialist in the Geography and Map Division.)

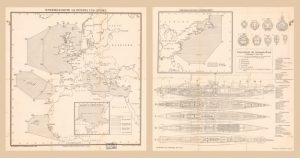

Sperrgebiete um Europa und Afrika. 1925. Geography and Map Division.

Soldiers leaping from trenches and charging into an apocalyptic no man’s land dominate the imagination when it comes to World War I. However, an equally dangerous and strategically critical war at sea was waged between the Central Powers and the Allies, with Germany and Great Britain as the primary belligerents. The primary strategy was to disrupt the flow of supplies, thereby diminishing the other side’s ability to fight.

In 1914, the Allies commenced a blockade, which included the draconian measure of declaring food as contraband of war. Germany responded with one of its own, using its submarine fleet, known as U-boats, to sink merchant ships. The map “Sperrgebiete um Europa und Afrika” (“Restricted zones Europe and Africa”) depicts areas where Germany threatened to sink both Allied and neutral merchant ships.

Although Germany publicized its plan, the strategy ran contrary to the accepted rules of war. The practice prior to attacking a merchant ship was to fire a warning shot; inspect the ship for contraband of war, and if found, evacuate the crew and passengers, providing them with safe refuge; or finally sink or capture the ship. This method was impractical for small submarines, which could not accommodate additional persons aboard. But more so, it sacrificed the submarine’s surprise attack potential. After weighing their options, the Germans proceeded with a shoot without warning policy that became known as “unrestricted submarine warfare.”

American civilians were soon after caught in the crossfire. On May 7, 1915, the passenger ship RMS Lusitania was torpedoed and sunk off of Ireland by a U-boat, and of the 1,959 people on board 1,198 died, including 128 Americans. President Woodrow Wilson was outraged, because he believed that Americans had the right to “Freedom of the Seas” and should be able to travel safely on any civilian ship despite the war. He demanded that the Germans conform to the rules of war. American newspapers explained the issue with maps that illustrated areas where Germans submarines were active as well as minefields.

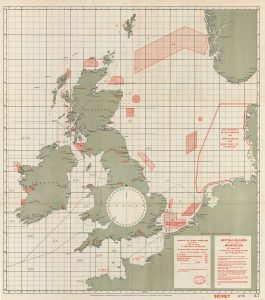

“British Islands: Approximate Positions of Minefields. 19th August 1918.” Hydrographic Department of the Admiralty, under superintendence of Rear-Admiral J.F. Parry, C.B. Hydrographer, August 6th, 1917. Geography and Map Division.

The Germans feared the political repercussions of their strategy and curtailed these attacks. Germany continued, however, to employ some 43,000 sea mines that claimed more than 500 merchant vessels by the end of war. The British Navy lost 44 warships and 225 auxiliaries to mines. The British, in response, constantly swept for mines that frequently threatened their naval facilities, commercial ports and ports in Ireland, which were often a stopover for ships sailing from North America. This blog post from World’s Revealed looks at these sea mines.

Britain hoped to use its superior surface fleet to destroy the German counterpart in Trafalgar-type engagement, an allusion to Admiral Horatio Nelson’s destruction of the French fleet in 1805. The opportunity came at the Battle of Jutland (May 31-June 1 1916), where the British lost 14 ships and more than 6,000 men, and the Germans lost 11 ships and more than 2,500 men. Though a German tactical victory and an utter shock to British pride, the Kaiser’s fleet never again seriously challenged British control of the North Sea and the blockade of Germany continued.

Desperation to break the deadlock in the land war and growing short of supplies, Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in 1917. Attacks were planned on all commercial vessels, which included attacks on American ships, as illustrated in the map “Amerikanisches Sperrgebeit.” In response, the United States severed diplomatic relations with Germany, and the two nations were at war within months.

The U-boat attacks were devastating. The map “Die Schiffsversenkungen unserer U-Boote” (“Ships sunk by our U-boats”) highlights the carnage. By the end of the war, Germany had sunk more than 5,000 merchant ships and more than 100 warships; tens of thousands of lives were lost. This was achieved at a high cost to the German navy, as 217 of its 351 submarines were sunk with a loss of more than 5,000 sailors. The German effort, nonetheless, could not overcome Allied sea power and their industrial capacity to replace lost ships and supplies.

More information on the Library’s World War I maps can be found in this guide.

World War I Centennial, 2017-2018: With the most comprehensive collection of multi-format World War I holdings in the nation, the Library of Congress is a unique resource for primary source materials, education plans, public programs and on-site visitor experiences about The Great War including exhibits, symposia and book talks.

January 10, 2017

Library in the News: December 2016 Edition

Happy New Year! Let’s look back on some of the Library’s headlines in December. Topping the news was the announcement of the new selections to the National Film Registry. Outlets really picked up on the heavy 80s influence of the list.

“It’s loaded with millennials,” said Christie D’Zurilla of The Los Angeles Times. “Ten of the 25 films selected by the Librarian of Congress this year were born after 1980.”

The Washington Post noted the teen angst theme of several movies on this year’s list, including “The Decline of Western Civilization,” “The Breakfast Club,” “Rushmore” and “Blackboard Jungle.” Reporter Michael O’Sullivan spoke with “Decline” director Penelope Spheeris, who said she doesn’t find it odd that thematically related films appear on the list.

“The youth-in-revolt genre has an enduring appeal, since adolescence and early adulthood are when we are forming our identities,” she said. “[The registry has] become a vital reference library for upcoming generations of young people.”

Slate Magazine said there is “a little something for everyone in the NFPB’s latest batch.”

The Library’s Veterans History Project also received media coverage in December, particularly with the 75th anniversary of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7. Several regional outlets shared stories of collecting efforts, including Honolulu Civil Beat, St. Louis Public Radio and the Brown County Democrat.

“How much cooler is that, that our kids can archive these living histories into the Library of Congress?” said Emily Lewellen, teacher at Brown County High School who works with the school’s History Club members.

Late November, the Library announced a collaboration with the Digital Public Library of America to share its rich digital resources with DPLA’s database of content records.

“This is an important partnership for both institutions, as it bolsters the DPLA’s role as a valuable nexus for cross-institutional data and ensures the accessibility of the LOC’s significant digital resources,” wrote Allison Meier for Hyperallergic.

“You don’t have to be an historian or cartographer to appreciate why this partnership is a big deal,” wrote William Fenton for PC Magazine. “The Library of Congress isn’t just the nation’s de facto library, but also the largest library in the world. It’s an institution that Americans can and should celebrate and, under the leadership of Librarian Carla Hayden, the LOC has crafted an ambitious strategic plan that will greatly expand its online presence. Digitization will benefit students, educators, researchers, and all inquisitive citizens, particularly those who do not live within commuting distance of Washington D.C.

LC in the News: December 2016 Edition

Happy New Year! Let’s look back on some of the Library’s headlines in December. Topping the news was the announcement of the new selections to the National Film Registry. Outlets really picked up on the heavy 80s influence of the list.

“It’s loaded with millennials,” said Christie D’Zurilla of The Los Angeles Times. “Ten of the 25 films selected by the Librarian of Congress this year were born after 1980.”

The Washington Post noted the teen angst theme of several movies on this year’s list, including “The Decline of Western Civilization,” “The Breakfast Club,” “Rushmore” and “Blackboard Jungle.” Reporter Michael O’Sullivan spoke with “Decline” director Penelope Spheeris, who said she doesn’t find it odd that thematically related films appear on the list.

“The youth-in-revolt genre has an enduring appeal, since adolescence and early adulthood are when we are forming our identities,” she said. “[The registry has] become a vital reference library for upcoming generations of young people.”

Slate Magazine said there is “a little something for everyone in the NFPB’s latest batch.”

The Library’s Veterans History Project also received media coverage in December, particularly with the 75th anniversary of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7. Several regional outlets shared stories of collecting efforts, including Honolulu Civil Beat, St. Louis Public Radio and the Brown County Democrat.

“How much cooler is that, that our kids can archive these living histories into the Library of Congress?” said Emily Lewellen, teacher at Brown County High School who works with the school’s History Club members.

Late November, the Library announced a collaboration with the Digital Public Library of America to share its rich digital resources with DPLA’s database of content records.

“This is an important partnership for both institutions, as it bolsters the DPLA’s role as a valuable nexus for cross-institutional data and ensures the accessibility of the LOC’s significant digital resources,” wrote Allison Meier for Hyperallergic.

“You don’t have to be an historian or cartographer to appreciate why this partnership is a big deal,” wrote William Fenton for PC Magazine. “The Library of Congress isn’t just the nation’s de facto library, but also the largest library in the world. It’s an institution that Americans can and should celebrate and, under the leadership of Librarian Carla Hayden, the LOC has crafted an ambitious strategic plan that will greatly expand its online presence. Digitization will benefit students, educators, researchers, and all inquisitive citizens, particularly those who do not live within commuting distance of Washington D.C.

January 5, 2017

On The Twelfth Night of Christmas

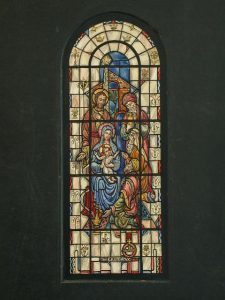

Design drawing for stained glass window showing The Epiphany, by J. & R. Lamb Studios. Prints and Photographs Division.

Just when you thought the holiday season was over, Carnival Season is excitedly waiting at its heels. I admit, my Christmas Tree and other decorations are still up, not only because I am a tad lazy when it comes to taking them down but also because traditionally they should be taken down on Twelfth Night. Depending on which faith, it’s either January 5 or January 6. The holiday is so called because traditionally, Christmas was a 12- day celebration, beginning on December 25. The confusion lies in whether you start counting on or after Christmas.

Concluding the 12 days of Christmas is Epiphany, or the manifestation of Jesus Christ to the world and the coming of the Magi, which is officially January 6. Many in my original neck of the woods also mark this as King’s Day, not only for religious purposes but for the start of Mardi Gras and king cake season. Shame on you should you eat a slice before you official should. (Guess what, I already have!)

In 1481, Leonardo da Vinci painted an altarpiece celebrating the “Adoration of the Magi.” In one of the preparatory drawings, he drew a perspective grid in order to place the architectural structures, human figures and animals in a realistically proportioned way. This study kept in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, was shown for the first time ever in the United States on Dec. 7-8, 2006, at the Library of Congress.

Act V. Scene I of “Twelfth Night,” by William Shakespeare. Prints and Photographs Division.

Also considered a time of merrymaking, some cultures mark the occasion by exchanging of gifts, and Twelfth Night, as the eve of the Epiphany, takes on a similar significance to Christmas Eve. In Tudor England, the Twelfth Night marked the end of an autumn/winter festival that started on All Hallows Eve, which is now celebrated as Halloween. On this day, the king and his upperechelon would become the peasants, and vise-versa. At the beginning of the Twelfth Night festival, a cake containing a bean was eaten. The person who found the bean became king and would run the feast. Midnight signaled the end of his rule and the world would return to normal.

Harkening back to this tradition is perhaps what influenced the turn of events in William Shakespeare’s comedy “Twelfth Night, or What You Will,” which centers on mistaken identity, long-lost siblings and a rather unconventional love triangle. By searching for “twelfth night” or “Shakespeare” in the Library’s online collections, you can find sheet music in “Music for the Nation: American Sheet Music, 1820-1860 and 1870-1885,” historical newspapers in Chronicling America, a variety of photographs and prints and this recording from The National Jukebox.

{mediaObjectId:'A2671ACD339C037CE0438C93F116037C',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

You can read further on Epiphany and how it’s represented in our folklife collections in this blog post from Folklife Today.

December 25, 2016

Pic of the Week: Glad Tree Tidings

Library of Congress patrons and staff gathered in the Great Hall to celebrate the holiday season. Photo by Shawn Miller.

As is our tradition, the Library of Congress has once again decorated the Great Hall with a tall tree for the holidays, full of lights and ornaments for the enjoyment of visitors. I’m not sure exactly how tall, but it takes staff using a small cherry picker to put together and decorate the tree. Set amidst the magnificence of the Great Hall, the tree veritably glows with a festive, holiday spirit.

If you’ve had the chance to visit the Library and enjoy the tree, make sure to follow us on Instagram at @librarycongress and post your own photos tagging the Library as well. There, you can also check out a great time-lapse video of the tree being put up!

We at the Library of Congress wish you and yours a merry Christmas and wonderful holiday season!

December 21, 2016

World War I: Lubok Posters in the World Digital Library

(The following guest post is by John Van Oudenaren, director for scholarly and educational programs at the Library of Congress.)

[image error]

A Heroic Feat by Non-Commissioned Officer Avvakum Volkov, Who Captured the Austrian Flag. 1914. Contributed by The British Library.

By the time the United States entered World War I in April 1917, the European powers had been fighting for more than two-and-a-half years. U.S. troops joined their British, French and Belgian allies in battles against Germany on the Western front, and a small number of U.S. soldiers were deployed to northern Italy. The United States was also allied as an “associated power” with Russia, which since August 1914 had been fighting Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire on the Eastern front.

Like all governments on both sides, the Russian authorities issued a steady stream of propaganda aimed at shoring up morale and convincing the Russian people that their wartime sacrifices were not in vain – that victory was sure to come. Among the most popular and effective forms of Russian propaganda were “luboki,” which were popular prints with simple, colorful graphics, generally used to illustrate a narrative. Lubok images were clear and easy to understand, aimed at people who were illiterate or had limited education. As part of its presentation of World War I as a global conflict, the World Digital Library includes a collection of 79 lubok posters contributed by the British Library and the National Library of Russia. These prints show Russian forces fighting soldiers of the Central Powers in fierce battles along the huge front stretching from the Baltic to the Black seas, as well as on the Caucasus front in eastern Turkey.

Shown is a typical lubok poster from a battle between Russian and Austrian troops early in the war in September 1914. It depicts a non-commissioned officer, Avvakum Volkov, a veteran of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, vanquishing a detachment of Austrian dragoons. The caption explains that Volkov and his men attacked a unit of 10 enlisted men and an officer. “Volkov decapitated the officer, engaged three dragoons and the flag bearer, and, with the enemy’s captured flag, headed back with his comrades. On the way they encountered a second Austrian patrol. Another desperate fight ensued, and ended with the flight of the enemy.”

The poster is typical of the genre, in which Russian forces often are depicted on horseback, slashing at their enemies with swords and lances. Hapless enemy soldiers fall in droves, often profusely bleeding. The illustrations generally show the Russians emerging unscathed from the fiercest of combats, although casualties sometimes are mentioned in the captions.

Propaganda such as this was of course highly misleading. Russia suffered more than 9 million casualties in World War I, including an estimated 1.7 million combat deaths. The economic and political strains caused by the war led to the February 1917 revolution and the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II on March 15, three weeks before the United States entered the war. With the Bolshevik Revolution of November 1918, Russia withdrew from the war and concluded a separate peace with Germany.

World War I Centennial, 2017-2018: With the most comprehensive collection of multi-format World War I holdings in the nation, the Library of Congress is a unique resource for primary source materials, education plans, public programs and on-site visitor experiences about The Great War including exhibits, symposia and book talks.

December 19, 2016

Highlighting the Holidays: Under the Mistletoe

Under the mistletoe. 1902. Prints and Photographs Division.

The holidays are full of many traditions – gift giving, sending cards, singing and cooking. Also kissing. If ever there was a time to pucker up, it’s in December, underneath the mistletoe. Washington Irving wrote in the 1800s, “young men have the privilege of kissing the girls under [mistletoe], plucking each time a berry from the bush. When the berries are all plucked the privilege ceases.”

The history of the symbolism of the mistletoe has a few different versions. In Norse mythology, Odin’s son Baldur was prophesied to die. So his mother, Frigg, went around securing an oath from all the plants and animals that each wouldn’t harm him. She forgot to check in with mistletoe, so Loki, up to no good, made an arrow from the plant and used it to kill Baldur. There seems to be a couple of ends to the story. Baldur was resurrected, and Frigg declared the mistletoe a symbol of love and vowed to kiss all those who passed under it. Alternatively, Frigg’s tears over her dead son became the berries of the plant, and she vowed not only that it would never again be used as a weapon but also that she would kiss anyone who passed beneath it.

Other romantic overtones came from the Celtic Druids in the first century, who viewed it as a symbol of fertility, vivacity, healing and even luck, because it could grow even in winter. Kissing may have begun with the Greeks, during Saturnalia and later during marriage ceremonies, because of the plant’s fertility powers. And the Romans were said to reconcile their wartime differences under the mistletoe because it represented peace.

Puck Christmas. Illustration by C.J. Taylor, 1895. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Library has in its collections a couple of books that make reference to both the Baldur and Druid stories. In this poem by Sarah Day in “From Mayflowers to Mistletoe,” Day writes “A song of Mistletoe, oh, ho, ho! ‘T is a plant that is olden in story: I decked for the Druid his victim’s last throe, to Baldur a death-shaft I sped from the bow, not a tribute that’s mine am I wont to forego; Behold me, the Mistletoe hoary!”

How the mistletoe tradition made the leap to holiday decoration isn’t clearly evident, short of the Druids using it in their Saturnalia celebrations, which was first observed on December 17.

In “A Vision of the Mistletoe,” by Maria Sears Brooks, a man dreams about the “mystic tie” that mistletoe has to “Christmas cheer.”

Ironically enough, certain varieties of the plant itself are poisonous. And, the plant is actually a parasite, the seeds of which attach themselves to other trees, literally taking root and stealing its host’s water and nutrients. How is that for romantic!

Perhaps this song from the Library’s National Jukebox collection will put you in the mood …

{mediaObjectId:'A2671ACD4562037CE0438C93F116037C',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

More of the Library’s historical treasures are highlighted here in celebration of the season.

Sources: history.com, Smithsonian Magazine, Live Science and mentalfloss.com

December 15, 2016

Witnesses to History

(The following was written by Barbara Orbach Natanson, head of the reference section in the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division, and featured in the November/December 2016 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

The Library’s documentary photograph collections provide a rich, visual record of the past century.

Since the advent of photography in the 19th century, people have recognized the power of images to communicate. In each generation, photographers have provided visual testimony of noteworthy and everyday events. Viewed as a whole, the Library’s documentary and photojournalism collections offer a visual timeline covering more than a century.

[image error]

Bodies of Confederate artillerymen lay near the Dunker Church after the Battle of Antietam, 1862. Alexander Gardner.

DOCUMENTING WAR

Some of the earliest large-scale documentary projects were records of war. Roger Fenton’s Crimean War photographs represent one of the earliest such efforts. During the spring of 1855, Fenton produced 360 photographs of the allied armies and British military camps.

With the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, photographer Mathew Brady planned to document the conflict between the Union and the Confederacy on a grand scale. Brady supervised a corps of traveling photographers and bought photos from private photographers fresh from the battlefield. Brady shocked America by displaying Alexander Gardner’s and James Gibson’s graphic photographs of the bloody Antietam battlefield. The New York Times said Brady “[brought] home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war.”

SURVEYING LAND AND PEOPLE

The post-Civil War period saw expanding use of the camera to document territories and peoples. In 1867, Alexander Gardner photographed the western frontier as a field photographer for the Union Pacific Railroad. His stereographic images bring scenery and people to life when viewed in 3-D through a stereograph viewer.

The U.S. government sponsored photographic surveys as part of several 19th-century exploratory expeditions led by Clarence King and George M. Wheeler. Stereographic photographs by Timothy O’Sullivan, William Bell and Andrew J. Russell allowed the public to see parts of the continent that few had witnessed first-hand.

[image error]

Sergei M. Prokudin-Gorskii shot this view of Russia’s Belaya River in color, 1910. Prokudin-Gorskii Collection.

The drive to survey vast territories photographically was an international one. Using emerging technological advances in color photography, Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii (1863-1944) documented expanses of the Russian Empire between 1909 and 1915. The Library has digitized his 1,902 triple-frame glass negatives, making color images of landscapes, architecture and people from that era accessible to modern viewers.

Lewis Hine (1874-1940) used his camera to document the need for social reform. Working for the National Child Labor Committee in the early-20th century, Hine’s photographs and detailed captions eloquently conveyed the plight of child workers.

Under the auspices of a succession of government agencies (Resettlement Administration; Farm Security Administration; Office of War Information), Roy Stryker headed perhaps the best-known documentary effort of the 20th century. Beginning in 1935, Stryker’s photo unit employed at various times photographers such as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Russell Lee, Arthur Rothstein, Ben Shahn, Jack Delano, Marion Post Wolcott, Gordon Parks, John Vachon and Carl Mydans, first documenting Depression-era rural dislocation and the lives of sharecroppers in the South, as well as conditions in the mid-western and western states. They went on to capture developments throughout the U.S. as the country mobilized for World War II. The project yielded more than 170,000 negatives that document many aspects of American life.

Contemporary photographers such as Carol M. Highsmith and Camilo Vergara continue to document the nation’s changing landscape. Highsmith has described her sense of urgency in documenting aspects of American life that are disappearing, such as barns, lighthouses, motor courts and eclectic roadside art. Vergara began photographing America’s in the 1970s with a focus on continuity and change. He explains, “My work asks basic questions: what was this place in the past, who uses it now and what are its current prospects?”

[image error]

Members of the picket line during the garment workers strike in

New York City, 1910, Bain News Service, George Grantham Bain Collection.

NEWS—AND PHOTOGRAPHS—FIT TO PRINT

Aided by the development of halftone technology at the end of the 19th century, newspapers and magazines could reproduce photographs more easily and cheaply.

George Grantham Bain, known as the “father of news photography,” recognized the hunger for pictorial news in the first decade of the 20th century. Bain employed photographers to capture newsworthy photos that he distributed to subscribing publications and, in turn collected photographs from them. The Bain Collection, comprising more than 40,000 glass negatives and corresponding prints, taken primarily in the 1910s and 1920s, richly document sports events, theater, celebrities, crime, strikes, disasters, public celebrations and political activities, including the woman suffrage campaign.

Soon joining Bain were two news photo businesses that took advantage of their proximity to the nation’s capital. The studio of George W. Harris & Martha Ewing specialized in portrait and news photography in Washington, D.C. More than 40,000 photographs show many aspects of the nation’s political and social life over the course of the first half of the 20th century. The National Photo Company subscription service, operated by Herbert French, generated more than 35,000 photographs starting around 1909 and continuing into the early 1930s.

[image error]

Arnold Schwarzenegger participates in the President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports, 1991. Maureen Keating, CQ Roll Call Photograph Collection.

Pictorial publishing expanded in popular magazines like Look. The Library of Congress acquired Look’s photographic archives when the magazine ceased publication in 1971. The black-and-white and color images— many unpublished—invite exploration of the personalities and pastimes of the 1950s and 1960s.

Similarly, the archives amassed by the New York World-Telegram & the Sun Newspaper and the U.S. News & World Report organizations, together comprising more than 2.2 million images, include many more photographs than the publications used. They document major world crises as well as passing fancies of the 20th century.

In recent years, the Library has acquired the photograph collections of Roll Call and Congressional Quarterly, two publications that cover activities on Capitol Hill. Comprising more than 300,000 black-and-white and color photographs, the images were taken between 1988 and 2000.

Through the Library’s commitment to preservation and access, these photographs, and all others in its custody, will continue to move and inform generations to come.

All photos from the Prints and Photographs Division.

December 14, 2016

What Do You Go to the Movies For?

Roger Rabbit, wrapped around Bob Hoskins in “Who Framed Roger Rabbit”

This year’s entries to the Library of Congress National Film Registry, 25 in all (bringing the grand total of films of cultural, historic or aesthetic value to be preserved for posterity to 700), will fulfill many of our reasons for going to the pictures:

“I go to the movies to be terrified.” – Well, we’re going to scare the feathers off you with Alfred Hitchcock’s “The Birds.” This 1963 horror show, starring Tippi Hedren and Rod Taylor, presses home the idea that there’s nothing more frightening than nature suddenly turning unnatural. A special shout-out to crew member Ray Berwick, who trained the birds of “The Birds.”

“I go to the movies to imagine the impossible.” – This year’s selections include “Lost Horizon,” (1937) which transported its cast, including Ronald Colman, Jane Wyatt and Sam Jaffe, to a Shangri-La of amazing sets; “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea,” (1916) the first picture to show undersea footage to a movie-house audience; and “Who Framed Roger Rabbit,” (1988) which commingled film footage with animation and was the last time Mel Blanc voiced Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck.

“I go to the movies to escape.” – You can escape into an inconceivably zany fairy tale such as “The Princess Bride” (1987) or you can go a little grittier and run off with “Thelma & Louise” (1991).

“I go to the movies to hum along.” – That’s easy to do with the Barbra Streisand vehicle “Funny Girl” (1968), a biopic about Ziegfeld Follies star Fannie Brice, or with Disney’s beloved animated musical “The Lion King” (1994).

“I go to the movies to learn things.” – This year’s registry offerings include “Atomic Café,” (1982) which samples TV and film resources of the post-WWII era to take a look at America’s obsession with nuclear annihilation; “The Decline of Western Civilization,” which documents the rise of LA’s punk-rock scene in the 1980s; “Paris is Burning,” which documents the gay/transgender/drag scene in New York in the 1980s; and the Solomon Sir Jones films, a collection of home movies shot in the late 1920s by an African American clergyman and businessman, documenting his community’s vast range of everyday activities.

“I go to the movies to remember what it is I’d like to forget.” – The decidedly non-PC cult classic “Putney Swope”(1969) is on this year’s list. The premise is promising – an African American is suddenly catapulted to the helm of a major Madison Avenue ad firm – but some of the preposterous ads and groaner ethnic jokes in this flick remind us why we made a beeline away from the cultural schtick of the ‘60s. For those of you who slunk through high school, there’s “The Breakfast Club” (1985), John Hughes’ salute to the kids with the ‘tudes.

Whatever you go to the movies for, enjoy this year’s entries in the Library of Congress National Film Registry – and don’t forget to nominate movies for next year’s list.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers