Library of Congress's Blog, page 135

February 19, 2016

For Multitudes, the Book of a Lifetime

Just as life is a motive force, so can a book be a motivating force in the lives of readers.

Author Harper Lee’s long life has ended, but the book for which she is best known, “To Kill A Mockingbird,” was for untold numbers of people all over the world their “book of a lifetime,” the book they considered to have the most impact on their lives and minds. It won the Pulitzer Prize and sold more than 30 million copies.

[image error]

Cover of the first edition of “To Kill A Mockingbird,” 1960

Evidence of this effect came through again and again when the Library of Congress, in 2012, presented an exhibition titled “Books That Shaped America,” inviting those who attended that exhibit and others who went to that year’s Library of Congress National Book Festival to cite the book that most shaped their lives. (In our NBF “Books That Shaped the World” informal survey in 2013, which drew more than 500 responses, “Mockingbird” was outflanked only by the Bible).

We also are proud to host an essay contest for young people, here at the Library, called “Letters About Literature,” in which children and teens write to an author, living or dead, who has made a major impression upon them. Daniel Le, who won honorable mention in this contest in 2008, wrote to Harper Lee:

Dear Ms. Lee,

I have only begun to appreciate the power of your work To Kill a Mockingbird. Even on my first reading, I was enthralled by this moral drama of good and evil set in the “deep” South during the Great Depression. I was most indignant when the verdict went against Tom Robinson, but I did not immediately relate it to any personal experience. At a family gathering, however, a chance discussion about your book unleashed a torrent of passionate personal stories from my usually reticent and reserved family. Clearly, your historical fiction about social injustice and discrimination struck a chord. My grandfather recounted how he silently endured racial epithets for years and how he had to pay blackmail to a white city inspector to keep his laundry open. My dad will never forget how his family was treated when they attempted to rent apartments in Manhattan’s Upper West Side in the 1960s. Speaking perfect English, he had no problem getting appointments to see the apartments on the phone. When he went with my grandparents to see the apartments, however, he was told pointedly, “We don’t rent to your kind.” (The rest of Daniel Le’s letter can be read here.)

I remember the effect that book had on my own family in the early 1960s, when it came out in print and very quickly was made into a movie we now consider a classic. My parents read the book and saw the film, and shortly after took my brother, my sister and me—ages 13, 11 and 7, respectively—to a matinee to see it, all together. They wanted to teach us what “character” meant.

Many fans hoped for another Harper Lee novel in vain. Then, through third parties, another work she had written earlier in her life came to light, and was published: “Go Set A Watchman.” It viewed the fictional lawyer Atticus Finch through a new, less-glowing lens, causing real disappointment to many readers.

Well, I haven’t read it. But even if I do, it won’t take the joy out of “Mockingbird” for me. Many authors of acknowledged masterpieces wrote other stuff too, and we don’t hold it against them: “Tom Sawyer” is not “Huckleberry Finn.” “Timon of Athens” doesn’t get performed, or even studied, as much as “Macbeth.”

Thanks, Harper Lee, for Atticus and Scout and Boo Radley. You said what you had to say, and for thousands upon thousands of people, its resonance still rings.

Pic of the Week: Combating Illiteracy

David Rubenstein, benefactor of the 2016 Library of Congress Literacy Awards, interviews Rubenstein Prize-winner Kyle Zimmer, president and CEO of First Books. Photo by Shawn Miller.

The Library of Congress on Wednesday honored the recipients of the Library of Congress Literacy Awards – three groups working to alleviate the scourge of illiteracy in this country and around the world. Recipients were First Book ($150,000 David M. Rubenstein Prize), United Through Reading ($50,000 American Prize) and Beanstalk ($50,000 International Prize).The Literacy Awards, first announced in January 2013, help support organizations working to alleviate the problems of illiteracy and aliteracy in the United States and worldwide. The awards highlight and reward organizations that do exemplary, innovative and easily replicable work.

“There’s something incredibly powerful about a child holding the same book in his hands that his mom had held, reading it to him from halfway around the world,” said Sally Ann Zoll, CEO of United Through Reading. The organization unites military families facing physical separation by helping them read together, no matter where they are in the world.

“It’s important to … join the cause, do something and make sure we can change the lives, change the story for thousands and thousands of children and parents,” said Beanstalk CEO Ginny Lunn. London-based Beanstalk uses a corps of volunteers to provide one-on-one reading assistance to children who struggle with their ability and confidence.

Concluding the program was a one-on-one interview with Rubenstein and First Book’s founder and CEO, Kyle Zimmer.

“We know every day that we have to grow faster, that we have to do more,” Zimmer said.

Sources: The Gazette, the Library of Congress staff newsletter

February 18, 2016

10 Stories: Glorious Food! Chronicling America

In celebration of the release of the 10 millionth page of Chronicling America, our free, online searchable database of historical U.S. newspapers, our reference librarians have selected some interesting subjects and articles from the archives. We’ve been sharing them in a series of Throwback Thursday #TBT blog posts.

Today we return to our historical newspaper archives for stories about food. Recipes, spreads for special occasions, peculiar ingredients and much more.

[image error]

“German Pickles,” illustration from the San Francisco Call, May 28, 1911.

“California Women Who Cook”

This regular feature in the San Francisco Call features, in its May 28, 1911, edition, a cornucopia of recipes and suggestions, from “Two Ways to Prepare Chicken” to “Some Excellent Raisin Recipes” to guides for the preparation of whole wheat bread, roast breast of veal with potato stuffing and German pickles.

“From Soup to Nuts on Christmas Day”

Both are appropriate holiday victuals, but this article from the New York Tribune of Dec. 19, 1915, offers much more, including Coeur Sensible aux Fraises (Iced Heart Sensible with Strawberries), Potatoes Champs Elysee and Chaudfroid of Pheasant Jeanette.

“War Bread”

War bread “is good bread when baked in a safe, sure oven of a Gas Range,” says Pacific Gas & Electric, not unexpectedly, in an ad complete with recipe (including lard!) from the Arizona Republican, January 9, 1918.

“State Chocolate Recipes”

In another installment of “California Women Who Cook,” various states of the union are represented by recipes for their traditional chocolate favorites, including that classic crowd-pleaser, Kansas Prune Chocolate. San Francisco Call, May 12, 1912.

“Mysteries of Cake Baking”

Expert Helen Louise Johnson reveals the hidden culinary arts, including “Cake-Baking of Ante-Bellum Days” and warns that there is “No Such Thing as Luck in Cooking,” in the Marion (Ohio) Daily Mirror, April 15, 1911.

“Peanut Butter Omelet”

Among other peanut butter recipes in this special section of “Helpful Hints for the Thrifty Farmer” is this unusual item that doesn’t sound too bad. Also included are a peanut butter loaf (with bread crumbs, rice and chopped olives) and peanut butter salad dressing. Williston (N.D.) Graphic, Feb. 27, 1919.

“Walnut Catsup”

There was a time when catsup was not particularly synonymous with tomatoes. The Chicago Day Book of Sept. 23, 1912, featured a recipe for the sauce based on walnuts, then described variants based on shellfish (oysters, mussels and cockles) and mushrooms.

“Possum”

“Senator Garland of Arkansas” (apparently Augustus Hill Garland, who served in the Senates of both the United States and the Confederacy) gives advice on the proper preparation technique for this critter in the Morehouse Clarion of Bastrop, La. of August 26, 1881. He observes, “Rather than miss him entirely … I would try to eat him in any way I could find him, and really I am of opinion that he is better hot or cold, according to the state he is in when I last partake of him.”

“Different Ways of Preparing Sweetbreads”

From the New York Tribute, Feb. 20, 1915, and including roasted, creamed, braised, croquettes, with peppers, and in salad. Yum.

“Two Recipes for Making Whiskey”

Because simply one will not do. The Watauga (N.C.) Democrat of May 20, 1909, freely admits to pilfering these two recipes from the Asheville Citizen. The first, oddly enough, requires a gallon of corn whiskey to start. The second “is a little more complicated, and perhaps it is well that this is so because most of the ingredients are rank poisons.” It would be interesting to know whether circulation for the paper dropped following this issue.

Speaking of Chronicling America, the National Endowment for the Humanities (our partner in the project) has launched a nationwide contest, challenging you to produce creative web-based projects using data pulled from the newspaper archives website. We’re looking for data visualizations, web-based tools or other innovative web-based projects using the open data found on Chronicling America. NEH will award cash prizes, and the contest closes June 15, 2016.

Launched by the Library of Congress and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) in 2007, Chronicling America provides enhanced and permanent access to historically significant newspapers published in the United States between 1836 and 1922. It is part of the National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP), a joint effort between the two agencies and partners in 40 states and territories. Start exploring the first draft of history today at chroniclingamerica.loc.gov and help us celebrate on Twitter and Facebook by sharing your findings and using the hashtags #ChronAm #10Million.

February 17, 2016

Found It!

(The following is featured in the January/February 2016 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

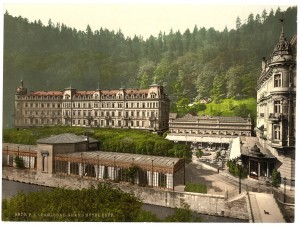

Grand Hotel Pupp, Carlsbad, Bohemia, Austro-Hungary. Prints and Photographs Division.

Nearly 1.6 million people came to the Library of Congress in 2015 to conduct research in its 21 reading rooms on Capitol Hill. More than 60 million users visited the Library’s website last year to access Library resources. Here are some examples of what researchers found.

Film director Wes Anderson: “The Library of Congress’s Photochrom Print Collection includes commercially produced pictures showing views of Europe around the turn of the 20th century,” Anderson told “The Telegraph.” They’re black- and-white photographs that have been colorized. “What you see when you look at these pictures are landscapes and cityscapes, from all over the world. … A huge number of them are from the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Prussia. These pictures were a great inspiration for “The Grand Budapest Hotel.” Many of the old hotels in these photographs still exist as buildings. But none of them exist as the places they once were.”

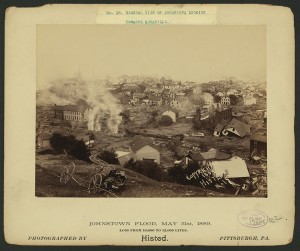

Aftermath of the Johnstown Flood, Ernest Walter Histed, May 3, 1889. Prints and Photographs Division.

Historian David McCullough: “I discovered my vocation here in the Library of Congress. I have done research on all my work at this great library. After seeing pictures of the 1889 flood in Johnstown, Pa., in the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division, I began writing my first history, ‘The Johnstown Flood’ (1968).” McCullough researched his latest book, “The Wright Brothers,” at the Library of Congress, where photographs and manuscript records of the aviation pioneers are housed. “I am more indebted to this great institution than I can say. It is the mother church of the library system in America.”

Theodore Roosevelt and William H. Taft, Brown Brothers, circa 1909. Prints and Photographs Division.

Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin: “For Teddy and Taft almost 90 percent of what I needed was at the Library of Congress” said Doris Kearns Goodwin about her 2013 book, “The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism.” Goodwin also spent years eviewing the Library’s collection of Lincoln papers for her 2006 book, “Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln,” from which the screenplay for the 2012 film “Lincoln” was adapted.

Musician, writer and actor Henry Rollins: “These people are all about collecting, databasing and preserving. I am in my element,” said Rollins about staff in the Library’s Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division. “We are having conversations about acid-free paper and Mylar L-sleeves! Be still, my fanatic heart. … A day of nonstop awe and inspiration. Whenever any great song or album gets lost in the ether, someone is deprived of the joy of hearing it, and the great effort of those who created and recorded the work is damaged. Thankfully, the fanatics are there to make sure the jam session never stops.”

February 16, 2016

All This Jazz

(The following is a story written by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library of Congress staff newsletter, The Gazette.)

[image error]

Sarah Vaughan performs at Café Society in 1946 in this photo by William Gottlieb. Music Division.

The human voice is music’s only pure instrument, jazz singer Nina Simone once wrote – it has notes no other instrument possesses.

“It’s like being between the keys of a piano,” Simone wrote in a draft of an unpublished autobiography recently discovered in a Library of Congress collection. “The notes are there, you can sing them, but they can’t be found on any instrument. That’s like me.”

Simone’s simple, typed note captures an essential truth about the art of jazz singing – the subject of a new exhibition at the Library of Congress.

“Jazz Singers,” an exploration of the lives and work of such great artists as Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald and Simone, opened in the Performing Arts Reading Room foyer in the Madison Building last week and runs through July 23. An online exhibition also includes additional material.

The exhibition was curated by Larry Appelbaum, a senior reference specialist in the Music Division, and directed by Betsy Nahum-Miller, a senior exhibit director in the Interpretive Programs Office.

The exhibition includes video clips candid snapshots, musical scores, personal notes, correspondence, drawings and watercolors covering more than nine decades of a uniquely American art form – and reveals something about what makes a jazz singer a jazz singer.

“All of these singers have something unique that is expressed with soul, creativity and artistry,” Appelbaum said. “What it really comes down to is their ability to tell you a story with music and lyric. They’re all great musical storytellers. And to see and hear how they created in the moment – interacting, swinging and improvising with others – is not just impressive and inspiring, it’s the essence of what jazz is about.”

The Music Division holds about 30 special collections of jazz materials documenting some of the form’s great figures: Fitzgerald, Charles Mingus, Max Roach, Carmen McRae, Dexter Gordon, Billy Taylor, Shirley Horn and Gerry Mulligan, whose sax is on permanent display outside the Performing Arts Reading Room.

“Jazz Singers,” drawing on those and other collections, reveals the men and women who made the music and their vital, vibrant and sometimes painful lives.

Trumpeter and singer Chet Baker became a soft-voiced icon of cool West Coast jazz in the 1950s – his recording of “My Funny Valentine” remains a much-loved milestone even six decades later. But Baker also was a self-destructive soul, a troubled side illustrated in the exhibition with a false-alarm suicide note drawn from a recently acquired cache of material.

“I’ve been trying to kill myself for a month by shooting speed balls with large quantities of cocain [sic] and heroin,” he wrote. “I’m now down to about 120 lbs and not looking well.”

The exhibition shows happier times, too: Abbey Lincoln appears relaxed and casual at home in a contact sheet of photos, Johnny Mathis writes Horn to say how much he loves her work, Mary Lou Williams offers McRae suggestions of material to cover, and 13 video clips showcase performers doing what they do best.

[image error]

A portrait of Nat “King” Cole taken by William P. Gottlieb in New York in 1946. Music Division.

Fitzgerald and Duke Ellington perform together in a rare clip from the 1959 Bell Telephone Hour, Holiday sings “Travelin’ Light” on a French television show and others clips feature McRae, Sarah Vaughan, Anita O’Day, The Mills Brothers, Jimmy Rushing, Fats Waller, Johnny Hartman, Luciana Souza and Jeri Southern.

“I wanted people to get a sense of the many different approaches to singing jazz, to feel it,” Appelbaum said. “Once you take in the exhibit, you’ll hopefully gain a deeper appreciation for what these artists accomplished and what it means to be a jazz singer.”

“Jazz Singers” encompasses what Quincy Jones called “the roots to the fruits”: early artists such as Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton and Ethel Waters, midcentury masters Holiday, Nat “King” Cole, McRae and Betty Carter and 21st-century performers Gregory Porter and Cécile McLorin Salvant.

Each generation, Appelbaum said, assimilates what’s gone before and produces creative artists who stretch the musical boundaries. No singer before Armstrong had taken such a daring and virtuosic approach to time and syncopation. Decades later, many performers incorporate aspects of other genres, such as hip-hop or R&B, into their style.

“Ask a creative jazz singer who they’re listening to and you might be surprised at how wide their tastes run, from jazz to classical, pop and dance music, to the latest from the underground,” he said. “We live in a shuffle age and tastes increasingly transcend traditional ideas of genre. …

“Everyone has their own way. It’s really about the individual and having your own voice.”

February 14, 2016

Rare Object of the Month: Unrequited Love for the Ages

(The following is a guest blog post written by Elizabeth Gettins, Library of Congress digital library specialist.)

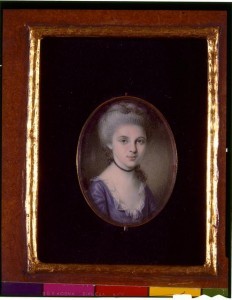

This month, the Rare Book of the Month is not actually a book but objects from the special collections within the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. In honor of Valentine’s Day, we take a peek into the love life of James Madison through the work of a remarkable early American artist by the name of Charles Willson Peale.

Fourth President of the United States James Madison (1751-1836) was called the “Father of the Bill of Rights,” as well as the “Father of the Constitution.” He was also instrumental in reestablishing the Library of Congress following the War of 1812.

James Madison miniature. Charles Willson Peale, 1783. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

While Madison is indeed an impressive historical figure, it appears that in person he may have been less than an appealing catch to the ladies. Madison was known to perpetually suffer from delicate health and was small of stature, even for the standards of his day. Records indicate that he was only five feet, four inches and never weighed more than 100 pounds. He was also known to be socially introverted. However, he had a keen mind and was a very diligent scholar – so diligent in fact that it was thought to further exacerbate his health conditions.

Most men of Madison’s era married by their mid-twenties. Yet Madison did not advance a marriage proposal until the relatively advanced age of 32. Catherine “Kitty” Floyd, the daughter of a Continental Congress delegate, caught his eye. In 1783, as tokens of their mutual love, Madison and Floyd exchanged ivory miniature portraits of themselves by the artist Charles Willson Peale. As a special sign of esteem, Madison included a braided lock of his hair. Unfortunately, this love was not destined to last as Kitty fell in love with another suitor and sent Madison a rejection letter. Understandably, Madison was crushed.

Verso of oval portrait miniature showing Madison’s hair in braided pattern. 1783. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

This short courtship is frozen in time by the beautifully delicate and charming portraiture created by Peale. Peale was an American renaissance man who rubbed elbows with many prominent politicians and businessmen of his day. He was born in 1741 in Queen Anne’s County, Maryland. At a young age, Peale showed promise in portraiture and studied under well-established artists of his time, including John Hesselius, John Singleton Copley, John Beale Bordley and Benjamin West.

Catherine “Kitty” Floyd portrait miniature. Charles Willson Peale, 1783. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Peale went on to become a prolific artist, painting the portraits of prominent men of his time including Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton. An interesting side note about Peale is that he named all of his children after artists or scientists. Three of his sons went on to paint themselves, including Rembrandt, Raphaelle and Titian Peale. Peale and his son’s works made contributions towards documenting an early American nation and also of helping to create an American sensibility in art.

While Madison’s love life did not travel an easy course, he did go on to have a happy ending. It was not until 11 years later that he advanced another marriage proposal. This time he was successful and, at the age of 43, he married he married Dolley Payne Todd (1768-1849) on Sept. 15, 1794. From all accounts, it was a happy marriage. Seventeen years his junior, Dolley was a widow that Madison likely encountered at social events in the nation’s capital. She was known for her social graces, which likely helped Madison’s popularity as president. The ever consummate hostess and decorator, Dolley went on to give definition to the role that the wife of an American president played. The concept of First Lady took shape around her pleasant and graceful entertaining skills.

Other Sources at the Library of Congress

From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division

Continental Congress Broadside Collection

Constitutional Convention Broadside Collection

The James Madison Pamphlet Collection

February 11, 2016

A Valentine for the Ages: The Biblical “Song of Songs”

(The following post is by Ann Brener, Hebraic area specialist in the Library’s African and Middle Eastern Division.)

With its rich nature imagery and enigmatic dream-like sequences, the “Song of Songs” (also known as the “Songs of Solomon”) is surely one of the world’s great love poems and one of the most popular books in the Old and New Testaments. A few lines are enough to entice any reader into its magic:

The fig-tree putteth forth her green figs, and the vines in blossom give forth their fragrance. Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away.

O my dove, that art in the clefts of the rock, in the secret places of the cliffs, let me see thy countenance, let me hear thy voice; for thy voice is sweet and thy countenance comely.

Take us the foxes, the little foxes that spoil the vineyards; for our vineyards are in blossom.

My beloved is mine, and I am his, that feedeth among the lilies.

Until the day ebbs and the shadows flee away, turn, my beloved, and be thou like a gazelle or a young hart upon the mountains of spices. (“Song of Songs” 2: 1-5)

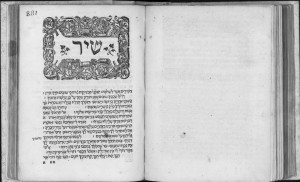

“Song of Songs” from the First Rabbinic Bible. Venice, 1517. African and Middle Eastern Division.

Though scholars often demur, the “Song of Songs” is traditionally attributed to King Solomon himself, ruler of the Kingdom of Israel around 960 B.C. Yet even this exalted attribution was not enough to guarantee the “Song of Songs” a place in the canon of sacred writ.

Ancient Jewish lore tells us that in the dark days following the disastrous uprising against Rome and the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 A.D., the Jewish sages met to canonize the various books of Holy Writ into a single Hebrew Bible, fearful lest the sacred writings be lost. In the ensuing debate over what to keep in the Bible and what to keep out, it was the great Rabbi Akiba who answered critics of the poem’s undeniably sensual nature, saying that “if other books of the Bible were sacred, then the ‘Song of Songs’ is the most sacred of all.” Thus the exquisite poem became one of the 24 books included in the Hebrew Bible, and, along with Ecclesiastes and Proverbs, one of the three biblical books traditionally ascribed to King Solomon.

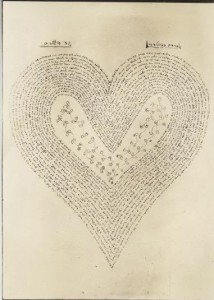

“Song of Songs” in micrography. Germany, 1920. African and Middle Eastern Division.

With the dawn of printing in the 15th century, the “Song of Songs” was amongst the first texts to roll off the press, and through the years it has served as a focus for artists and printers alike – all of which has resulted in the “goodly treasures new and old” now lining the shelves of the Library of Congress, to quote from the “Song of Songs” itself (7: 13). One of the most precious early editions is the one included in a Hebrew Bible printed in Venice, 1517, by the fabled Daniel Bomberg, printer of so many first editions of Hebrew classics. Known as the First Rabbinic Bible, this was the first printed Bible to incorporate the “masorah” – the body of ancient Judaic tradition relating to the correct textual reading of the Hebrew Bible.

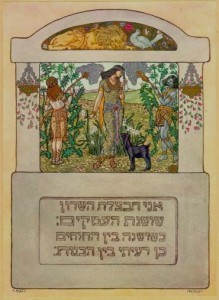

“Song of Songs” illustrated by Ze’ev Raban. Berlin, 1923.

African and Middle Eastern Division.

A most unique edition of the “Song of Songs” is a lovely example of Hebrew micrography created in 1920 Germany, by Abraham Stollerman. Micrography is the scribal practice of employing minuscule script to create abstract shapes or figurative designs and is an art form found in some of the most beautiful Hebrew manuscripts from the Middle Ages. The heart-shaped image, less than five inches tall, contains the “Song of Songs” in its entirety – all eight chapters.

This “Song of Songs” was printed in Berlin in 1923, but its illustrations were created by , Ze’ev Raban (1890-1970), an artist based in Jerusalem. Raban is perhaps the foremost representative of the Bezalel School of Art, founded in Jerusalem in 1906 and famous for its distinctive blend of Art Nouveau with motifs from the ancient Near East.

“Song of Songs” illustrated by Mordechai Beck. Jerusalem, ca. 1999. African and Middle Eastern Division.

This magnificent limited-edition “Song of Songs” features the etchings of Mordechai Beck, whose sinuous shapes in black and white emphasize the sensual dimension of the text. Featuring the calligraphy of Yitshak Pludwinski, it was published in Jerusalem around 1999.

These four editions of the “Song of Songs,” each so different in style, offer a unique glimpse into Jewish culture and history across the ages. They are, however, only a sampling from the collections of the Hebraic Section, and it is our hope that readers will take the opportunity to come view these and other editions for themselves.

February 9, 2016

Library in the News: January 2016 Edition

January was a month filled with awards and honors.

The Library welcomed Gene Luen Yang as the fifth National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature.

Michael Cavna of The Washington Post covered the inauguration ceremony and wrote, “Yang — a charismatic, high-energy speaker — was able to present himself dually as both authentically dimensional scholar and simplified cartoon character. This touch was brilliant, because not only did Yang offer a humbly nerdy avatar that the grade-schoolers could instantly warm up to, and perhaps some even identify with; he also was displaying the very strength that most distinguishes him as an ambassador: the ability to connect through the magical marriage of words and pictures.”

“In reflecting on his new role as ambassador, Mr. Yang said he found his wife, Theresa, a development director for an elementary school, a tremendous resource. He said that he was inspired by her program for encouraging students to read and write in different genres and that she was enthusiastic about the ambassadorship,” said George Gene Gustines for the New York Times.

“Does anyone say no to this? It’s an amazing opportunity,” Yang told Sue Corbett of .

Yang was on the Kojo Nnamdai Show to discuss his role, Asian-American identity and comic book culture.

Kelly McEvers of spoke with Yang about becoming the first graphic novelist to be named ambassador.

Yang was also featured in stories on CCTV and Washington Post .

The Library of Congress Gershwin Prize concert honoring Willie Nelson aired nationwide on PBS in January. Many outlets not only reported on the broadcast but also on Nelson’s Gershwin-inspired album that drops in February.

Speaking of prizes, winners of the 2015 Holland Prize for architectural drawing were announced in January. The Smithsonian Magazine and Fine Books & Collections Magazine highlighted the winners, who were actually only honorable mentions.

February 8, 2016

Trending: African American History Month

(The following article by Audrey Fischer is from the January/February 2016 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

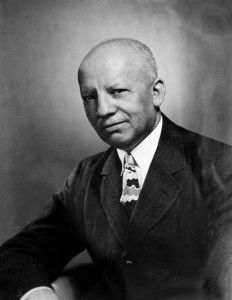

Carter G. Woodson, 1947. Prints and Photographs Division.

One man’s dedication to a field of study inspired the moniker “the father of African American history.”

With this year’s theme of “Hallowed Grounds: Sites of African American Memories,” will be celebrated in schools, libraries and other cultural institutions throughout the month of February.

One such sacred ground is 1538 Ninth Street N.W. in Washington, D.C., home to Carter G. Woodson, pictured above, (1875-1950), the Harvard-educated historian who established Black History Week in 1926. The property was declared a National Historic Site in 1976—the same year that the recognition of African Americans’ contributions to the nation was extended to a month-long celebration.

In his “Message on the Observance of Black History Month” in February 1976, President Gerald Ford acknowledged Woodson’s founding of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASAALH) as a way to document those contributions. The organization was founded in 1915 at the house on Ninth Street, where Carter lived until his death in 1950. With more than 25 branches, the membership organization holds an annual convention in cities across the nation.

Woodson believed that, “Those who have no record of what their forebears have accomplished lose the inspiration which comes from the teaching of biography and history.” He devoted his life to researching, publishing and increasing public awareness of black history and culture.

Woodson researched his dissertation at the Library of Congress, where he was encouraged by Manuscript Division Chief J. Franklin Jameson to seek funding to further his goals. With a grant from the Carnegie Foundation, Woodson founded the ASAALH. In 1929 and 1938, Woodson donated his papers to the Library of Congress. The bulk of the collection’s 18,000 items have been microfilmed and the film is available in the Library’s Manuscript Reading Room.

The collection includes primary documents relating to African-American life and history during the slavery, Reconstruction and “New South” eras. It also includes material related to Woodson’s editing of the “Encyclopedia Africana,” a comprehensive guide to African peoples, leaders, and luminaries in Africa, the United States, South America, the Caribbean, and worldwide. The unpublished research for that ambitious publication, along with other unique items, makes the collection a valuable resource for scholars and students of African American history.

February 5, 2016

New Blog Series: New Online

(The following is a guest post by William Kellum, manager in the Library’s Web Services Division.)

This is the first post in a new monthly series highlighting new collections, items and presentations on the Library’s website. After checking out the items mentioned here, be sure to visit some of our other blogs that highlight our collections in more depth, such as Picture This, Now See Hear and Worlds Revealed.

New Collections and Items:

The Library’s American Archive of Public Broadcasting (AAPB) – a collaboration with the WGBH Educational Foundation – announced this week the acquisition of the New Hampshire Public Radio’s digital collection of interviews and speeches by presidential candidates from 1995-2007. The entire collection – nearly 100 hours of content – is now online, along with other presidential campaign content from the AAPB collection, in a new curated, free presentation, “Voices of Democracy: Public Media and Presidential Elections.”

The Library’s Manuscripts Division has been hard at work digitizing collections of historic American documents, with dozens of primary source collections online (you can see the full list here).

The Salmon P. Chase Papers consist of 12,500 items from the papers of this former Ohio governor, Lincoln cabinet official and Supreme Court justice. The papers focus chiefly on Chase’s legal career, activities as an abolitionist, involvement in Ohio and national politics, tenure as secretary of the treasury (1861-1864), influence on national finance and service as chief justice of the United States Supreme Court (1864-1873).

The William Tecumseh Sherman Papers include approximately 18,000 items of correspondence, a volume of recollections during and after the Mexican War, military documents, printed matter, memorabilia and manuscripts of Sherman’s “Memoirs.” The manuscript of the “Memoirs” and a long narrative of wartime experiences supplement the correspondence for the Civil War period. The correspondence in the collection is particularly strong for the years when Sherman served as commanding general of the army (1869-1883).

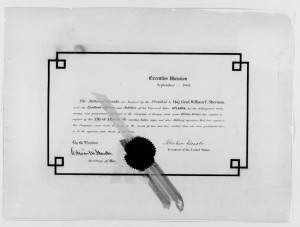

Sherman’s papers also include thousands of pages of letters and personal recollections, along with historical documents like this certificate (left) of thanks signed by President Abraham Lincoln, awarded to Sherman after his capture of Atlanta in 1864. Like many of our digitized items, users can freely download a high resolution image of this document.

Sherman’s papers also include thousands of pages of letters and personal recollections, along with historical documents like this certificate (left) of thanks signed by President Abraham Lincoln, awarded to Sherman after his capture of Atlanta in 1864. Like many of our digitized items, users can freely download a high resolution image of this document.

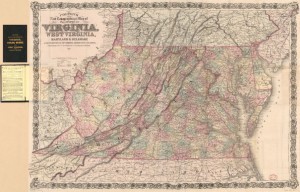

The Library’s extensive digitization efforts include a stream of individual items, in addition to the types of full collections mentioned above. We frequently add new digitized items to loc.gov via “one off” scanning – for example, this 1876 map (below) – “Colton’s new topographical map of the states of Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland & Delaware”

You can use the deep zoom feature on the item’s resource view to see roads, rivers, railroads, and more. Check out more digitized maps.

Five new digitized items are added to the Poetry and Literature Center’s Archive of Hispanic Literature on Tape and Archive of Recorded Poetry and Literature each month, along with biographies of the poets and authors. Check out this recording of Robert Creeley reading his poems (with commentary), recorded in the Library’s Recording Laboratory in 1961.

Upgrades and Updates:

American Memory was, for many years, the Library’s flagship online presence, a ground-breaking collection of digitized primary sources and scholarly materials. It is gradually being migrated to new presentations that allow for a modern web experience, as well as updated searching and browsing. Recent migrations include the American Folklife Center’s Captain Pearl R. Nye: Life on the Ohio and Erie Canal Collection, featuring 75 recordings from 1937-38 (by John, Ruby, and Alan Lomax) of songs documenting life on the canal. From the Law Library and the Rare Books Divisions comes The Slaves and the Courts, 1740-1860 Collection, featuring materials drawn from 105 manuscripts and books associated with the Dred Scott case and the abolitionist activities of John Brown, John Quincy Adams, and William Lloyd Garrison.

Also in a new presentation is An American Ballroom Companion: Dance Instruction Manuals, ca. 1490 to 1920, bringing you social dance guides dating back to 1490. Library experts have helpfully grouped the materials topically, in case you want to find for example, Anti-dance materials.

The Library holds hundreds of lectures, concerts, poetry readings, author talks and more each year, most of which are filmed and made available online via our video portal. We’ve recently been re-digitizing thousands of videos that have previously only been available in low resolution legacy formats, including updating more than 1,700 webcasts to new, high quality MP4 video.

{mediaObjectId:'2925E1E8728000E6E0538C93F11600E6',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

In this video, Library Music Specialist Larry Applebaum conducts a fascinating interview with the late music legend Allen Toussaint on the New Orleans piano tradition, Professor Longhair, the challenges of songwriting and producing, and the impact of Hurricane Katrina.

The Veterans History Project has recently upgraded thousands of video interviews from legacy formats to a high quality presentation accessible on any device. Search and browse the collection at loc.gov/vets, or see highlighted presentations like Experiencing War.

February is African American History Month – we’ve recently updated our with links to featured content from collaborators at the Smithsonian, National Endowment for the Humanities, National Park Service and the National Archives.

Next month we’ll be back with a new collection of digitized items from the Rosa Parks Papers, new archived Web Site content, improvements to our user interface, and more.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers