Library of Congress's Blog, page 137

January 7, 2016

A New Ambassador for Reading

(The following is a story written by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library of Congress staff newsletter, The Gazette.)

Gene Luen Yang addresses the audience at the 2014 National Book Festival gala. Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

There’s something special, author Gene Luen Yang says, about the first time a reader encounters a literary character that shares the same cultural background.

In his case, the character was Jubilation Lee, an X-Men comic-book figure who, like Yang, was a Chinese-American with immigrant parents but who, unlike Yang, could release explosive plasmoids and detonate matter at a subatomic level.

Jubilation, aka Jubilee, was one of the few Asian-American characters Yang saw in any media as a child in California in the 1980s – a lack of cultural diversity he felt keenly then and wants authors today to correct.

“For readers who are part of the majority culture, it’s important to have diversity because one of the functions of literature is to grow empathy and compassion in the reader,” Yang said by phone last week. “You need windows into other people’s lives in order to do that.

“For readers from minority communities, you need the diverse books just so you can see yourself reflected. Maybe it’s superficial, but there is something validating about seeing your story portrayed on a page.”

Yang now has a new platform to share that message: This week, the Library of Congress, the Children’s Book Council and Every Child a Reader named him national ambassador for young people’s literature – the first graphic novelist to serve in the position.

The program was established in 2008 to highlight the importance of young people’s literature to lifelong literacy, education and the betterment of young people’s lives. The ambassador serves a two-year term, appearing at events around the country and encouraging young people to read.

A Natural Storyteller

The young Yang wasn’t an especially prolific reader.

Early in grade school, a teacher would line up students from Yang’s class by the number of pages they’d read in a month. The leaders would take first pick from a table of prizes. Yang, usually near the end of the line, got the leftovers – the Tootsie Rolls no one else wanted.

“I was one of the slowest readers in my class,” he said.

Still, Yang felt naturally drawn to storytelling.

Both of Yang’s parents immigrated to the U.S. – his father, an electrical engineer, from Taiwan and his programmer mother from Hong Kong. Mom and Dad, seeking a way to connect their son with the culture they’d left, told Gene “a ton” of stories from their homelands.

Yang soon found he wanted to tell stories of his own. Early in grade school, he began keeping a notebook of his drawings and writings.

“It was always there,” Yang said. “Storytelling seemed natural to me, largely because of the kind of family I was growing up in.”

Eventually, Mom bought him his first comic book – DC Comics Presents Superman #57 – and Yang discovered the medium that would change his life.

“There’s something about the combination of words and pictures that really fascinated me,” Yang said. “[Words are] a much more precise instrument of communication. But when you’re trying to communicate emotions through pictures, it’s almost like you can put an emotion directly in a reader’s gut – almost like bypassing their brain.”

Finding a Calling

Yang didn’t expect to make writing a career. He majored in a “more practical” subject – computer science – at the University of California, Berkeley, with a minor in creative writing.

He figured he’d hold a full-time job and do graphic novels on the side – a self-published, money-losing labor of love.

“I just thought that whenever I put out a comic I would be losing anywhere from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars because I would be printing it up with my own money,” Yang said. “Some people, they play golf for fun and they lose a ton of money at that. I will make comic books for fun.”

That’s what happened, at first. After graduating in 1995, Yang took a job writing software code. But it didn’t feel quite right.

In college, he’d been involved in youth ministry, a gratifying experience. “It felt like something I was meant to do,” he said.

So, Yang embarked on a five-day silent retreat to think through his life.

“It’s hard not to talk that long,” he said. “But what it allowed me to do was think a little more clearly about my life without all the noise and make some decisions.”

The big decision: Quit code-writing and teach computer science and math at Bishop O’Dowd, a Catholic high school in Oakland, California.

He loved it.

“There is something like a teacher’s high,” Yang said. “There’s something about sitting down with a student and watching them struggle and seeing it click that is extremely satisfying. That makes you feel like it’s a pointer to the meaning of life.”

A Blossoming Career

All the while, Yang was writing.

In 1997, he began self-publishing his own comics with “Gordon Yamamoto and the King of the Geeks.” More followed, and Yang eventually signed with a publisher.

In 2006, he published “American Born Chinese” – the first graphic novel to be named a finalist for the National Book Award and the first to win the Printz award as the best book for young adults. In 2013, his “Boxers and Saints” also was named a National Book Award finalist.

Following the success of “American Born Chinese,” Yang increasingly found himself pulled away from teaching by his blossoming writing career.

Last June, after 17 years at Bishop O’Dowd, Yang quit to devote himself full-time to writing and, for the next two years, to his work as ambassador.

Yang frequently discusses the importance of diversity in literature – diverse books, diverse characters, diverse authors – and chose as his platform “Reading Without Walls.”

That is “just a fancy way” to say he hopes to get children to explore through reading – different literary forms, different cultures and the lives of people who are different from them.

“Stories can be both a mirror and a window,” Yang said. “They can be a mirror into your own experience and a window into somebody else’s. In order for stories to effectively serve both of those purposes, we do need diverse books.”

January 6, 2016

Library in the News: December 2015 Edition

While the new year is upon us, the Library’s headlines in December are worth looking back on.

Topping the news was the announcement of the new selections to the National Film Registry. Outlets noted recognizable films such as “Ghostbusters” and “Top Gun” along with some of the list’s more obscure titles.

“If there are any ghosts lurking in the Library of Congress, they’d do well to watch their backs, because they’ll soon be keeping company with a cadre of their fiercest enemies,” wrote Eliza Berman for .

Indiewire highlighted the diversity of the films, including those that featured the work of African Americans, both as main subjects and major creative forces.

Deadline called the validation by the National Film Registry better than the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval.

Charles Bramesco of Screen Crush wrote, “The United States government does a whole lot of unsavory things … But from time to time, the government also does wonderful things that make us very happy, and that is where the National Registry of Film comes in. Devoted specifically to the preservation of ‘culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant films,’ the NRF is the Library of Congress’ way of securing the future of countless important films for generations to come.”

Other national outlets running stories included CBS News, The Associated Press, USA Today, the Los Angeles Times, Entertainment Weekly and PBS Newshour.

In other movie news, “Star Wars” has been everywhere lately, and the Library has gotten in on some of the action. In December, the Library hosted a slate of children’s authors behind Disney’s Star Wars saga books.

“If there is any doubt whether the next generation — the new hope — will embrace the forthcoming Star Wars film, the hundreds of excited shrieks bouncing off the Library of Congress walls yesterday should be taken as the sound of high-decibel reassurance,” wrote Michael Cavna for The Washington Post.

“And to the librarians in attendance, as well as to a journalist, could anything be more encouraging than the ear-piercing cry of hundreds of happy kids shouting: ‘May the books be with you!’?”

Fast Forward covered the event and did brief interviews with the authors.

Mashable writer Lance Ulanoff had the opportunity to watch the original, unrestored 1977 “Star Wars” film.

“The librarian finds my name on a Post-It Note and directs me to a nearby desk with a Dell Computer running Windows 7,” he wrote. “On it are six files that comprise the entirety of the original ‘Star Wars’ negative transfer.

“If ‘Star Wars’ had finished its theatrical run and then been played on TV for the next near-half century without any extra care given to its image quality or aesthetics, this is likely how it would appear for everyone. It’s kind of a thrill.”

Also in entertainment, the Library acquired a collection of kinescopes, videotapes, 16 mm and Super 8 home movies of legendary comedian Ernie Kovacs and his wife, singer-actress-comedienne Edie Adams. Broadcasting & Cable, The Hollywood Reporter and Variety ran stories.

The Library also acquired a significant collection of oral histories provided by responders to the devastating Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attack on the New York World Trade Center. Time, DCist and the Associated Press picked up the announcement.

Speaking of collections, NPR gave an animated take to the Library’s series of panoramic photos of the Thomas Jefferson Building during construction. Enjoy!

NPR also wrote a great piece on the Library’s map collections, and spoke with Library curator John Hessler.

“As beautiful as these maps are, no one will ever again use them to get from point A to point B. So what’s the point of the collection?” said reporter Ari Shapiro. “‘Most maps aren’t to get from point A to point B,’ Hessler says. ‘Most maps are about how we as a civilization, as different cultures, perceive our lives in this box that we live in. All human activity takes place in space, and cartography is the thing that lets us keep track of that space.’”

And, the Library continues to receive accolades for its various projects and initiatives. Slate named the American Archive for Public Broadcasting as a top digital history project for 2015. The Daily Beast named “Facing Change” as a top photography book in 2015. And, Red Tricycle called the Library’s Young Reader’s Center a place every D.C. parent should know about.

December 29, 2015

To Come A Calling

“‘Le jour de l’an,’ as the French call the first day of January, is indeed the principal day of the year to those who still keep up the custom of calling and receiving calls. But in New York it is a custom which is in danger of falling into desuetude, owing to the size of the city and the growth of its population. There are, however, other towns and ‘much country’ … outside of New York, and there are still hospitable boards at which the happy and the light-hearted, the gay and the thoughtful, may meet and exchange wishes for a happy New-Year.” ~ “Manners and Social Usages,” by Mrs. John Sherwood, 1887.

[image error]

Happy New Year. Published by Currier & Ives, 1876. Prints and Photographs Division.

I love going through the Library’s collections of historical documents – whether its books, letters, newspaper articles, pamphlets or dance instruction manuals, I always find a little slice of history that makes me laugh a little, scratch my head or be appreciative for the things we can learn from the past.

While the quadrille or polonaise may no longer be the fashion, etiquette never really goes out of style. Some themes are universal and the advice rings true.

In Sherwood’s book, there is a whole chapter on gentlemen making calls on New Year’s Day.

“To those who receive calls we would say that it is well, if possible, to have every arrangement made two or three days before New Year’s, as the visiting begins early – sometimes at eleven o’clock – if the caller means to make a goodly day,” the book notes.

As someone who can’t stand it when people pop by last minute and unannounced, I can get behind this polite request.

The manual also encourages hostesses to provide refreshment for her callers.

“A lady who expects to have many calls, and who wishes to offer refreshments, should have hot tea and coffee and a bowl of punch on a convenient table … The best table is one which is furnished with boned turkey, jellied tongues, and pâtés, sandwiches, and similar dishes, with cake and fruit as decorative additions.”

[image error]Drawing by William Leroy Jacobs, 1917. Prints and Photographs Division.

I’m from the South, and it’s par for the course to always attempt to feed visitors, whether they are family, close acquaintances or complete strangers.

The chapter continues with some social mannerisms that might not have their place in today’s society. Calling cards anyone? We would just text or Facebook.

“Manners and Social Usages” is part of an online collection of more than 200 social dance manuals, anti-dance manuals, histories, etiquette treatises and other related content dating from 1490-1920.

The Library’s collections include numerous books on etiquette. A quick catalog search on “etiquette” revealed more than 430 books, most with an electronic resource available through the Internet Archive or HathiTrust.

“The multiplicity of other entertainments, the unseen yet all-powerful influence of fashion, these things mould the world insensibly. Yet in a thousand homes, thousands of cordial hands will be extended on the great First of January, and to all of them we wish a Happy New Year,” concludes the chapter in Mrs. Sherwood’s book. Sage words that resound today.

December 28, 2015

Reddit AMA on VHP Jan. 4

The following is a guest post by Monica Mohindra, head of program coordination and communication for the Library’s Veterans History Project.

Bob Patrick

Bob Patrick, director of the Library of Congress Veterans History Project (VHP), along with VHP staff, will answer your questions in a Reddit “Ask Me Anything” (AMA) session beginning at 9 a.m. (ET) on January 4, 2016.

Established in 2000 via a unanimous act of Congress, VHP collects oral histories and memoirs from U.S. veterans, as well as original photos, letters, artwork, military papers and other documents. Reliant completely on volunteers to record and submit these firsthand accounts, we have amassed more than 99,000 collections, and that number grows every week.

It’s easy to create a historic collection at the Library of Congress with and for the veteran in your life. All it takes is a veteran willing to tell his or her story, an interviewer to ask them about his or her service, and a recording device to capture the interview. Eligible collections will include a 30-minute (or longer) interview; 10 or more original photos, letters or documents; or a written memoir of 20 pages or more. Tips, guidelines and the required forms are in the VHP field kit.

[image error]

Edwin Mark Trawczynski, in uniform, standing against a jeep at Charlie Aid Station, Vietnam, March 1969. Veterans History Project. http://memory.loc.gov/diglib/vhp-stor...

To make these collections available and accessible for generations to come, we stabilize, preserve and securely store them here at the Library of Congress. We make the original materials available to researchers, Congress and the general public in person at the American Folklife Center Reading Room in the Library of Congress. Additionally, some 16,000 collections are available online.

On January 4, please ask us anything about how we collect, preserve and make available our collections, the individuals in our archives and their stories, how to participate, or any other aspect of the Veterans History Project.

On the day of the AMA, join us on the AskHistorians subreddit. To participate, you must have a Reddit account. If you don’t make it to the AMA in time to have your question answered, you can always email us at vohp@loc.gov.

December 25, 2015

Pic of the Week: Oh Christmas Tree!

Great Hall Christmas tree. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Once again, the Library of Congress has decorated the Great Hall with a tall tree for the holidays, full of lights and ornaments for the enjoyment of visitors. It makes a lovely temporary addition to the magnificence of the space and never fails to put me in a festive spirit. If you’ve had the chance to visit the Library and enjoy the tree, make sure to follow us on Instagram at @librarycongress and post your own photos tagging the Library as well.

We at the Library of Congress blog wish you and yours a merry Christmas and wonderful holiday season!

December 23, 2015

Highlighting the Holidays: An Armenian “Three Magi” at the Library of Congress

(The following is a guest post by Levon Avdoyan, Armenian and Georgian area specialist in the African and Middle Eastern Division.)

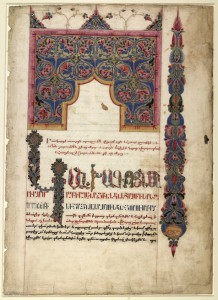

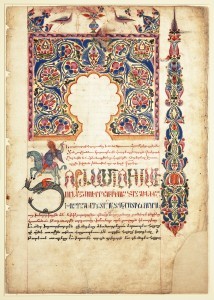

17th century Armenian calligraphy sheet featuring the “three magi.” African and Middle Eastern Division.

When I began working at the Library of Congress in 1992 as the Armenian and Georgian Area Specialist to the Near East Section of the African and Middle Eastern Division, it was as if a wonderfully extended Christmas began. I had certainly used the collections before then for my own research, but now I found myself with direct responsibility for an amazingly beautiful collection of Armenian manuscripts, illuminations, fabrics and documents.

The section is home to an important collection of Middle Eastern book covers and several rich collections of disbound calligraphy sheets from many of the languages of the Middle East. These and other items were procured in the 1930s from Kirkor Minassian, a dealer in fine Islamic and near Eastern art with establishments both in New York and Paris.

Of these calligraphy sheets, 17 are from Armenian manuscripts, and from these, six leaves come from a 17th century Haysmawurk‘ (Lectionary /Synaxary) – collections that provided the celebrants and worshipers with the daily textual readings associated with the various saints’ days and religious feasts throughout the ecclesiastical year. As these leaves were removed from a larger manuscript, we have no indication of the date of its creation nor, indeed, of the identities of the scribe who copied the manuscript or of the artist who sumptuously illustrated it. It is likely both from the palaeography (the style of the letters) and the artistic style of the illuminations that the manuscript was a production of the 17th century.

Leaf depicting the feast of Easter. African and Middle Eastern Division.

A particular leaf from that exceptional Armenian lectionary presents us with an intimate portrayal of the magi as they present their gifts to the infant Jesus. The regal magi are juxtaposed with Mary and Jesus set among the animals in attendance and Joseph standing in the background. The theme of the visit of the magi to the infant Jesus is a common one in Armenian manuscript illuminations, each of which reflects the artistic traditions of the era in which it was drawn. This beautiful example certainly can be enjoyed as a unique painting of the event, but as with all our collections, it can also fit into a broader historical narrative and exploration.

When I look at this particular representation of the well-known tradition, my thoughts lead to another intriguing aspect of the magi especially in the ancient Armenian tradition. A magus was not only a noble or royal personage, he was also a priest in the Zoroastrian religion. In 65 A.D., following a treaty of peace between Rome and the Persian Parthian Empire, the young magus and Parthian candidate to the Armenian throne, Tiridates I, journeyed to Rome to receive the regalia of kingship from the Emperor Nero (37 – 68 A.D.). So spectacular was his nine-month journey that several classical Greek and Latin authors described its magnificence. The description of people along the route gathering to mark its package indicates that its splendor was widely reported and appreciated.

One noted scholar of the 20th century, Ernst Herzfeld (1879 – 1948), went so far as to theorize that this journey of the Magus Tiridates, so well-known to the ancient world, might even have influenced the biblical narrative of the legendary three magi and their journey to the infant Jesus.

Ornate leaf dedicated to the feast of St. John the Baptist depicts St. George, whose image is defaced. African and Middle Eastern Division.

Whatever the truth of the matter, the cycle would be fulfilled in the early fourth century A.D. when Tiridates I’s descendent, Tiridates III, decreed that Christianity was the state religion of the Kingdom of Greater Armenia. Thus, according to the late fourth century Greek ecclesiastical historian Sozomenos, Armenia became the first nation to make Christianity its state religion.

Similar studies can certainly be based on several of the remaining leaves as well. There is a particularly ornate leaf dedicated to the feast of Easter, as well as another for the feast day of St. John the Baptist. What is curious about the latter is that while the text is clearly dedicated to St. John, the illumination on the page depicts St. George fighting the dragon and the saint is unexplainably defaced. Why that image for St. John? Why was that defacement?

What is so marvelous about the varied custodial collections of the Library of Congress is that they serve a variety of disciplines and thus as the focus of research for scholars in many of them.

Indeed, the eventual digitization of these sheets will allow art historians around the world to examine them and perhaps further identify them. And who knows? Other sheets from the same manuscript might be found, leading to its virtual reconstruction!

More of the Library’s historical treasures are highlighted here in celebration of the season.

December 22, 2015

Highlighting the Holidays: A Camel Line Item

A camel walked into Mount Vernon … sounds like the beginning of a rather offbeat joke. However, such is not the case. On Dec. 29, 1787, our nation’s soon-to-be first president, at home on his estate in Alexandria, Virginia, played host to a rather exotic animal for the holidays.

[image error]

Aladdin. Photo courtesy of George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

I first heard this story from a friend of mine who works at Mount Vernon. Every year, the estate brings in Aladdin the camel for its Candlelight Christmas festivities in an attempt to recreate life and experiences from Washington’s time. I thought it quite fascinating that Washington had such a tradition and figured that perhaps he employed a live nativity for his 18th century holiday celebrations or brought the camel in for the enjoyment of his step-grandchildren, George and Nelly Custis.

The complete George Washington Papers collection from the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress consists of approximately 65,000 documents. Included in the collection are his financial accounts. Washington was pretty meticulous about his accounts and documented expenditures both public and private.

His entry for Dec. 29 reveals a payment of 18 shillings to “the man who brought a camel from Alex. for a show.”

According to Mary V. Thompson of Mount Vernon, there is nothing in the Library’s records that indicate how the camel ended up at the estate or truly why.

“It might be that Washington learned there was a camel in town and invited the handler to bring it to his plantation,” she said. “It is also just as likely that the pair arrived in Alexandria, learned that Washington lived 10 miles or so down the road and, knowing he was famous and probably had money, decided to make the trip on their own.”

While the records are certainly no secret among scholars, their formidable financial formats make them somewhat complicated and hard to decipher. They’ve been seldom used in comparison to Washington’s diaries and correspondence. Currently, the University of Virginia is embarking on a project to publish them in book and digital form.

[image error]

Page in Washington’s ledger book indicating expenditure for a camel. Manuscript Division.

What these records do reveal are the interesting spending habits of our first president. During his life, Washington was responsible for millions of dollars in public and private expenditures for his household, his wife Martha’s estates, his agricultural and milling business enterprises, his land investments, the Virginia militia, the Continental Army and the federal government.

“On one hand he’s a farmer, on the other a colonial. He thinks of himself as English, so he wants to be ‘fashionable,’” says Julie Miller, early American historian in the Manuscript Division.

Washington was particularly concerned with fashionable appearances and, according to Miller, wrote about it so often that he abbreviated the word to “fash.” He exported his tobacco crop to London to pay for the luxuries and other goods he would import, such as gloves, ribbon, fabric, china, even delicate Chinese table ornaments for his home in Philadelphia. There’s an item for a “pair of gloves for Kennedy to wear.” According to Miller, the gloves were for one of Washington’s slaves to better handle said ornaments.

“He was the first president of the United States, so he wanted to present well to foreign diplomats,” she added.

Washington also kept records of his charitable donations, including money given to beggars, refugees and needy family members. A curious item to note is a lottery ticket he bought from a soldier, who was selling pieces of land in order to raise money for himself.

“His spending was typical for a man of his ilk, but because he was wealthy, he bore the brunt of it,” said Miller. “He was at the center of his neighborhood, and a lot of people relied on him.”

[image error]

George Washington’s estate, Mount Vernon. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith, between 1980 and 2006. Prints and Photographs Division.

His military accounts are also interesting. There wasn’t a division between his home and military life. While Washington was commander in chief of the Continental Army, he refused to accept a salary and, instead, claimed only his expenses. These expenses included not only his personal accounts but expenses for his headquarters, secret intelligence and traveling expenses for his headquarters and guards.

Washington’s financial accounts are full of nuggets of information that further add to our understanding of the man himself. While we may view him as a larger-than-life historical figure, he was simply a man of his time. I even found line items of money exchanged playing cards and billiards!

A further look into Washington’s financial records can be found in these blog posts: on his weaving workshop and his business dealings with women.

December 21, 2015

Rare Book of the Month: “King Winter” – A Book to Bring in the Season

(The following is a guest blog post written by Elizabeth Gettins, Library of Congress digital library specialist.)

[image error]

“King Winter,” by Gustav W. Seitz. 1859. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

You’ve heard of Jack Frost and most certainly St. Nicholas. But how about King Winter?

a rare German children’s book written by Gustav W. Seitz and published around 1859 in Hamburg, borrows from Germanic and Norse traditions with a winter solstice figure like that of Father Time or Father Winter.

King Winter serves as the embodiment of the Christmas Spirit as he leaves his palace of snow to bring winter to the land and reward obedient children with holiday sweets. He also has helpers who are the personification of winter’s effects, including Queen Winter who “spreads all over the earth, a carpet of downy snow,” and Jack Frost who is the king’s right hand man and decorates the world in frost and ice.

It is said of Jack Frost: “Old Jack is a good and sturdy fellow, and serves their Majesties well; He’s here he’s there he’s everywhere. And does more than I can tell.”

The Scandinavian notion of King Winter who rewards good children with presents has undergone a number of transformations through time. In the third century, he becomes the Christian Saint Nicholas. And in modern times, we widely know this character as Santa Claus, the jovial bearded old man who wears a red suit and delivers presents to children on his sleigh driven by eight reindeer.

[image error]

Illustration from the book showing icicles being hung.

The charming illustrations throughout this book are rendered by process called chromolithography, which is a type of lithography. Lithography is a form of printing with oil and water that is impressed onto a plate made of metal or stone and then is stamped onto paper leaving a graphic image. With chromolithography, two or more applications of color are impressed individually on the same graphic image, creating a multi-colored print. Previous to the invention of this process, pages were hand-colored. The process was long, tedious and often expensive. The advent of lithography brought about mass production of prints in books, and chromolithography improved upon the visual richness of this medium.

This children’s book is from the Juvenile Collection within the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Over time, the Library of Congress has assembled an immense collection of American children’s books, and the Rare Book Division has brought together approximately 15,000 volumes of particular interest. Though the overwhelming majority of books in the collection originated in America, there are distinguished British and continental books and American editions of works of foreign authors as well.

Other Resources at the Library of Congress

Digital Collection of Rare Children’s Books

Images from the Prints and Photographs Division of Jack Frost:

Have I had a good time? I’ve been painting the town white for two nights

Winter at last

Sheet Music written about Jack Frost from the Music Division:

Jack Frost’s Arrival

Jack Frost Galop

Little Jack Frost

December 17, 2015

Highlighting the Holidays: A Tale of Two Publishings

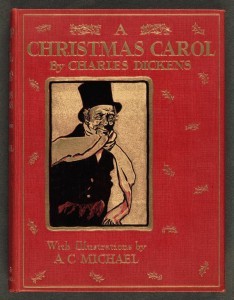

“A Christmas Carol,” by Charles Dickens. New York, Hodder and Stoughton, 1911. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

On this day in 1843, the Charles Dickens classic “A Christmas Carol” was published. Or was it? While researching the book’s history, there appeared to be some confusion over the date, with many sources confirming December 19 as the day Ebenezer Scrooge was introduced to readers.

As it turns out, the book has a somewhat complicated publishing history, owing to different copies that were made.

Dickens feverishly wrote his classic Christmas tale in about six weeks. Because of the disappointment of his serialized “Martin Chuzzlewit,” the author was hoping to produce something that would be both popular and profitable. Dickens set out to tell the tale of a miserly old man called on to repent his ways and make “mankind … charity, mercy, forbearance and benevolence” his business.

Finished by the end of November 1843, Dickens worked with his publishers Chapman and Hall to produce the work through a rather unorthodox arrangement – he incurred all the costs of the publishing but would also gain all the profits. Dickens was certain his book would be a financial success.

However, “A Christmas Carol” proved to be costly to produce, due to Dickens’ insistence on a lavish format. An article in The Guardian’s book blog notes the author required “a fancy binding stamped with gold lettering on the spine and front cover; gilded edges on the paper all around; four full-page, hand-colored etchings and four woodcuts by John Leech; half-title and title pages printed in bright red and green; and hand-colored green endpapers to match the green of the title page.”

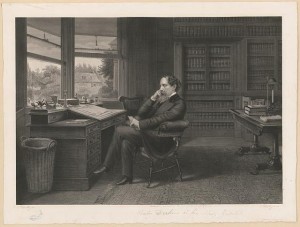

Charles Dickens in his study at Gadshill Place. Samuel Hollyer, 1875. Prints and Photographs Division.

Dickens scrapped some of this initial plan and changed out the green title page to blue. And while the green endpapers were first choice, at some point in the publishing process, they were switched out for yellow.

On Dec. 17. 1843, Dickens was given presentation copies to hand out among friends and acquaintances. The known copies had the red and blue title page and yellow endpapers. It’s also interesting to note some text discrepancies.

In these early copies, chapters are designated as “Stave I,” “Stave II” and so forth, and the Table of Contents also lists the staves with Roman numerals. However, in the original, uncorrected text, Stave I is designated with a Roman numeral while the rest of the chapters have the numbers written out.

Ultimately, copies of “A Christmas Carol” exist in various forms, with combinations of title pages, endpapers and chapter headings.

The Library holds the first edition, first issue (with title papers in red and blue and green end papers) in addition to one with the yellow endpapers. Both have the described “Stave I” of the first chapter heading followed by the uncorrected text.

On Dec. 19, Chapman and Hall released an initial print run of 6,000 copies of “A Christmas Carol” that sold out by Christmas Eve. Cost of the book was five shillings. Unfortunately, the overwhelming public response didn’t equal a large sum of money in Dickens’ pocket. Even after numerous printings into the next year, his profits were only about £726.

In America, interest was slow to take off, perhaps owing to Dickens’ criticisms in “American Notes for General Circulation,” a recounting of his trip to the states in 1842.

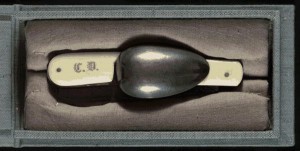

The traveling cutlery kit owned by Charles Dickens, marked with his initials and used by him during his travels to the United States in the 1860s. Steel spoon, knife and corkscrew unfold from ivory-covered case. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Needless to say, “A Christmas Carol” is firmly ensconced in literary heritage – and even in theater, movies and music! In addition to the rare presentation copies, the Library holds numerous other editions including this digitized copy from 1911.

The Library also holds first editions of many important Dickens’ works, including “David Copperfield,” “A Tale of Two Cities,” “Nicholas Nickleby,” “Master Humphrey’s Clock,” “The Old Curiosity Shop,” “Baraby Rudge,” “Little Dorrit,” “Our Mutual Friend,” “The Mystery of Edwin Drood,” “Oliver Twist,” “Sketches by Boz” and “Great Expectations,” among others. Our collections even include his traveling kit and walking stick.

For further reading about the Dickens’ classic, check out this blog post from the Inside Adams blog and this one from the Library’s National Audio-Video Conservation Center.

And make sure to join us over the next few days as we highlight more historical treasures in celebration of the holiday season. You can catch up on previous years here. Happy Holidays!

Sources: history.com, John J. Burns Library Blog, The Victorian Web

December 16, 2015

Good Timing for a Sliming

This year’s list of 25 noteworthy films named to the Library of Congress National Film Registry is out, and it includes some well-known favorites: “Ghostbusters,” “The Shawshank Redemption,” “Top Gun,” even the original Douglas Fairbanks vehicle “Zorro.” Films are annually named to the registry that are culturally, historically or aesthetically important; the object is preservation for posterity. Each film named must be at least 10 years old.

[image error]

The many frames making up the short, historic film “The Sneeze”

Ghostbusters – when you hear that word, do you think of marshmallows, or green slime? There’s probably some sort of Rorschach-y test there – leads this year’s subcategory that might be termed “tales of the weird.” In addition to the 1984 movie about a small business staffed by Bill Murray, Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis that went around vacuuming up ectoplasms, this year’s list also includes the 1931 Spanish-language version of “Dracula” (which some reviewers consider better than the Bela Lugosi version in English) and a 1906 early special-effects movie, “Dream of the Rarebit Fiend,” about a man who overeats the cheesy dish known as Welsh Rarebit, then falls into a nightmare-ridden sleep. It was based on a comic strip by the famed Winsor McCay, who also created the dreamlike “Little Nemo” strip and was among the pioneers of early animation. Later in his career, he also drew editorial cartoons.

The other big subcategory this year might be titled “Heroes and Anti-Heroes.” In addition to Zorro, based on a script written and submitted by Douglas Fairbanks under a pen name when he realized his career playing leads in romantic comedies was fading, this year’s list includes the movies “Top Gun” (1986) starring Tom Cruise, “John Henry and the Inky-Poo” (1946) which animates the folktale of the steel-drivin’ man who works himself to death proving his superiority to a steel-driving machine, and “Hail the Conquering Hero” (1944), a wry comedy about a Marine driven from the service by hay fever who is forced to pretend to be a hero, because he told his mother a set of tall tales in letters he wrote home before mustering out.

The list also includes the 1979 Peter Sellers/Shirley MacLaine film “Being There,” based on a Jerzy Kosinski novel; “Black and Tan” (1929), a brief movie starring Duke Ellington and an African-American cast and set at the Cotton Club; “L.A. Confidential,” the 1997 homage to film noir starring Russell Crowe and and Kevin Spacey; “A Fool There Was” (1915), the movie that introduced the world to Theda Bara, the original “vamp”; and “The Shawshank Redemption,” the Tim Robbins/Morgan Freeman prison-friendship movie that many movie fans consider their favorite film.

There are also some historic rarities: “The Sneeze” (1894), a film made by the Edison studios and originally presented as a published sequence of photos; and “Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One,” a 1968 film by African-American documentary-maker William Greaves, who also co-hosted and produced the show “Black Journal” on public TV. Greaves’ film is a movie about making a movie, and a lot more.

You can, and should, nominate films for next year’s National Film Registry: a list of films that are yet-undesignated is here.

Enjoy the movies.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers