Library of Congress's Blog, page 142

August 26, 2015

The Ghost Writer of the “Seaman’s Ghost”

The following post has been written by Sierriana Terry, one of 36 college students who participated in the 10-week Library of Congress Junior Fellow Summer Intern Program. A senior at North Carolina Central University studying music performance with a licensure in K-12 education, Terry worked in the Library’s Music Division. Her plan after the program is to attend graduate school and study musicology (music history).

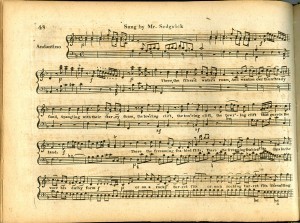

“The Shipwrek’d Shipman’s Ghost,” credited to Stephen Storace manuscript. Music Division.

As part of the Junior Fellows program, I have had the opportunity to catalog and research different sheet music collections. The David Lewin Papers, the Early American Sheet Music Collection and the Koussevitzky Commissions are major projects I worked on, just to name a few. The physical copies of these collections are housed in the Library’s Music Division, each containing sheet music original to the topic (i.e. Early American Sheet Music contains sheet music written pre-1820 by American composers and publishers).

I encountered quite an interesting item while working on the Early American Sheet Music collection: a manuscript of a song “The Shipwrecked Seaman’s Ghost” from “The Pirates” (an opera), credited to English composer Stephen Storace. Closely examining the manuscript, I noticed notes on the back (originally I assumed them to be initial sketches of the song) that appeared to be from a basic music theory lesson. The writing had several labels on each staff such as “principal chords” and solfège symbols for each note, which led me to assume that someone copied the song to practice for a singing lesson.

I cataloged the hand as “unknown,” for the hand on the manuscript and Storace’s hand were not a match according to the Library’s resources. I could not help but wonder, “Why would this be in this collection if it’s from an English opera?” After completing a few more items in the collection I decided to conduct more research on the manuscript.

Notes on page two appear to be a music theory lesson.

Using the Library’s staff and resources, I was able to find that “The Pirates” was composed by Stephen Storace – a composer whose comic operas were popular during their time – and premiered in 1792. It was well received by audiences and is considered to be Storace’s best composition. Opera at this time in England and early America could often resemble a musical potpourri, or a set or series of thematically connected songs. By looking at the score, there are no characteristics of a “proper” opera, including characters, plot and separate libretto.

Through the Library’s website I found a 1790 print edition of the opera and consulted it as a possible lead. Immediately, I noticed that none of the songs in the opera contained proper titles; each one had listed the performer(s) at the top as a title. As I skimmed through the score, I had to find the manuscript by the notation and words. After finding the song, I encountered two differences between the manuscript version of the song and the printed score – the first being that the manuscript is actually incomplete and the second, a modified bass clef in the piano accompaniment. Slightly frustrated coming to another “dead end,” I put the manuscript aside, hoping I could find something later.

The original version of the song in the opera “The Pirates.”

I moved back to the other items in the box and saw a published song, also from “The Pirates,” credited to Stephen Storace and published by B. Carr in Philadelphia. I referred back to the opera using the sheet music in front of me as a reference to find the same difference I found with the manuscript – a modified bass clef part in the piano accompaniment. I conducted some research on B. Carr and came across the name Benjamin Carr. Carr was an American composer, publisher, singer and teacher also known as the “Father of Philadelphia Music.” Born in London, he traveled to Philadelphia in 1793 with a stage company and remained there for a short period of time publishing and selling music. In the 1790s, Carr became the most important and prolific music publisher in America. Also, he was one of the founding members of the Musical Fund Society (one of the oldest musical societies in America) of Philadelphia.

My theory is that Carr received a copy of the score and published the songs, while giving them titles and revamping the bass clef. Unfortunately, I have not been able to find anything in Carr’s hand to match to the hand of the manuscript, but it is plausible that it is indeed his hand.

The Library’s collections and resources have many fascinating stories to tell, which several of the Junior Fellow interns have discovered. You can read about them here.

August 20, 2015

DICE-y Digitization

The following post is by Elizabeth Pieri, one of 36 college students who participated in the Library’s Junior Fellow Summer Intern Program. She’s in her fourth year at Rochester Institute of Technology, as a motion picture science major. Because her program focuses on the fundamental imaging technologies used in the motion picture industry, she was able to apply her knowledge of imaging analysis and programming to her Library project. Pieri was also able to attend meetings and tours that pertained to the film and motion picture industry, which she found beneficial because of her interests within her field of study.

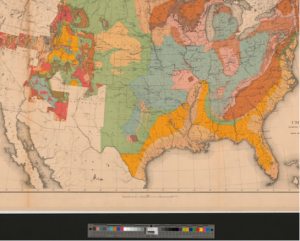

What do you think this map really looks like? Pick one! (answer below)

Only one of these is accurate to the original, but any one of these could be. How do we know which one is right?

The Library of Congress has pioneered the effort to develop a system to measure the quality of digital imaging, including the analysis of color quality. Starting in 2008, the Library began development of the Digital Image Conformance Evaluation Program (DICE). This program has become the reference tool used by cultural heritage digitization centers worldwide and has helped to improve the quality of digitization of our cultural treasures.

My project involves helping Lei He, a digital imaging specialist in the Library, develop an open source version of this system that can be freely distributed to cultural heritage institutions worldwide. Specifically, I am writing the code and building the interface using MatLab, a scientific programming environment that I learned at Rochester Institute of Technology.

Correct image of the map. The Geography and Map Division scans every object with an object level target.

Color accuracy in digitization is critically important but really difficult to achieve. So which map is right? We measure the color values in the DICE target that is imaged with the map and evaluate the data in DICE. You can see the target under the map in the correct image here on the right.

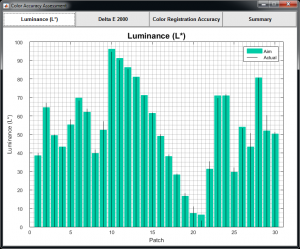

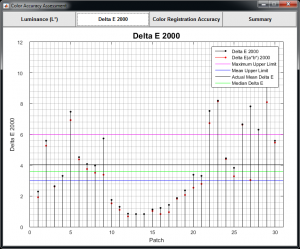

DICE reports the accuracy of the reproduction, displaying measurements of both luminance (brightness) and the color references on the target.

Luminance

Color difference

To ensure quality images, DICE is used very frequently across the Library. It has been used in the process of digitizing the Americana Vault collection, the Rosa Parks collection, the safety negatives of the Farm Security Administration and the field projects of the American Folklife Center, just to name a few.

The Library’s goal is to release this tool in January of 2016 with the next Federal Agencies Digitization Guidelines Inititiave (FADGI) still image digitization guidelines update. (See the guidelines here.) Combined with the new imaging guidelines, the tool will help improve digitization worldwide. Who would have guessed that the Library of Congress is on the forefront of digital imaging? Many people don’t realize the huge scope of projects the Library has taken on and what a service they provide to the public.

August 19, 2015

Expert’s Corner: Collection Development Officer Joseph Puccio

(The following story is featured in the July/August 2015 issue of the LCM, which you can read in it’s entirety here.)

Collection Development Officer Joseph Puccio discusses the Library’s collection-building today and tomorrow.

Photo by Shawn Miller

When I began my career at the Library of Congress in 1983 as a freshly minted library school graduate, I was astounded by the depth and breadth of the collections, comprising more than 79 million items. Those collections were all physical (analog) items, and they have continued to grow. The Library’s analog collection today totals more than 160 million items. In recent years, a huge amount of digitized collection material and born-digital items has been amassed, too–now consuming more than five petabytes of storage space.

The Library’s acquisitions programs for physical materials, with their supporting policies and technical infrastructure, are long-established and extremely effective. A set of over 70 Collections Policy Statements and Supplementary Guidelines documents guide the institution’s acquisitions and selection operations. These policies were developed over decades and continue to be updated. They provide the policy framework to support the Library’s responsibilities to serve the Congress as well as the United States government as a whole, the scholarly community and the general public. The policies provide a plan for developing the collections and maintaining their existing strengths. They set forth the scope, level of collecting intensity and goals sought by the Library to fulfill its service mission.

Our digital collecting programs, for the most part, are still in the process of being fully developed, with several successfully implemented. These efforts fall under the same framework of our analog collecting policies. However, a range of challenges–both technical and intellectual–must be met.

On the technical side is the challenge of the multiplicity of formats in which digital materials are produced, and the fact that the technology is constantly advancing. Thus, building and maintaining a system to ingest, preserve and provide access to digital content requires continuing modification.

A major consideration is the long-term sustainability of the digital materials. We are concerned about access to the content today and in the future. Another major factor in working with digital content is respecting use limitations imposed by the rights holders (usually creators or publishers).

But the biggest challenge is to decide what to collect and in what format. We do not have the resources to collect all available digital content–not even close. So, the questions we ask include what does the Congress need to support its work now? What will researchers need in 100 years or 500 years? What content best reflects America’s history and should be preserved and made accessible in perpetuity?

Those are questions we asked–and still ask– regarding analog materials. Such questions are even more critical in the realm of digital collecting. Although the policies provide guidance, the reality is that selection decisions–whether for analog or digital material–often require the expert judgment of Library staff members.

As the Library’s digital collecting program expands and matures, policies will continue to evolve. For example, our policy for U.S. newspapers states that we collect those that meet certain criteria, including those that are national in scope or coverage. For decades, we have met that mandate by acquiring paper issues for current use and microfilm for the permanent collection. How will that policy be applied in an environment where the newspapers themselves are available in multiple digital formats and a publication’s content is available separately, via one or more websites and through aggregated databases? Choices will need to be made, and the policies will need to be reviewed and updated on a continuing basis to meet the current and future needs of our users.

August 17, 2015

A Founder and a Firebrand

The nation and the world are mourning the passing of civil-rights activist Julian Bond, who died on Saturday in Florida at age 75. Brought up in an intellectual family, he was a skinny, witty, articulate young man when he helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, in 1960, traveling around the south to organize civil-rights and voter-registration drives.

Julian Bond, in youth

He interrupted his education at Morehouse College to participate in the crucial years of the civil-rights movement, then returned to school in 1971. With Morris Dees, he co-founded the Southern Poverty Law Center in Alabama. He later served as chairman of the NAACP and taught at American University and at the University of Virginia.

In 1965, Bond – who had been vocal in his opposition to the Vietnam War – was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act. The chamber tried to bar his entry as a lawmaker on grounds he had opposed the war. Although a U.S. District Court supported the Georgia House in the dispute, ultimately in 1966 the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the House to seat Bond, saying its grounds for barring him violated his free-speech rights. He went on to serve four terms in the Georgia House and six terms in the Georgia Senate.

He was also nominated in 1968 for vice president of the United States – becoming the first African American to be so nominated – at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. He was, however, too young to serve under the limits set by the U.S. Constitution. Bond later ran an unsuccessful campaign for Congress.

Julian Bond appears in many of the Library’s major civil-rights collections, including the NAACP Papers, the SNCC Collection and the American Folklife Center’s Civil Rights History Project Collection. A poet and author, he also narrated the prize-winning public television documentary “Eyes on the Prize.” He supported same-sex marriage rights.

Here, he narrates the introduction to the current Library of Congress exhibition, “The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom.”

Rare Book of the Month: Francis Bacon, A Thinker’s Thinker

(The following is a guest blog post written by Elizabeth Gettins, Library of Congress digital library specialist. Every month, the Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division will highlight a unique book from its collections, and the Library of Congress blog will take an in-depth look at the historical volume. Make sure to check back again next month!)

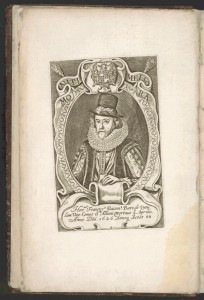

Front matter portrait of Francis Bacon. ” Sylva Sylvarum,” 1683. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

The Rare Book and Special Collections Division’s Book of the Month for August 2015 is This seminal work is comprised of multiple texts written by Francis Bacon (1561-1626). Bacon was an English humanist known as the father of empiricism or the scientific method. Empiricism was a revolutionary idea for its time, which postulated that observing the world through an organized process and without preconceived notion was the way to arrive at truth. This fundamental tenet established the scientific practice of methodology that is still in practice today.

Bacon was an exceedingly well-rounded thinker and a true Renaissance man, making contributions to philosophy, rhetoric, science, politics, law and literature. “Sylva Sylvarum” contains many of his ideas on philosophy and science and was published posthumously in 1683 by William Rawley, who was Bacon’s literary executor.

The first work in “Sylva Sylvarum” is titled “Natural History” and is divided into 10 centuries of thought. In glancing at the listings, one struggles a bit with its font and Old English, although with a little effort the entries can be deciphered. Below is a listing of the line of scientific observation along with a sampling of the types of topics that are explored within these fields.

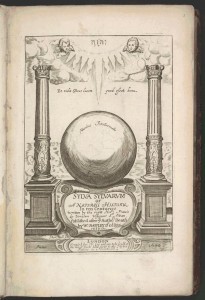

Frontispiece Illustration from “Sylva Sylvarum”

The listings have been tweaked a bit to make them easier for the modern English reader to understand, but one will likely notice that the works appear somewhat random, oddly organized and perhaps fanciful to the modern mind. Bacon himself commented that they are an “indigestible heap of particulars.”

Century I: “Straining and percolation,” including topics of artificial springs, the secret nature of flame and the power of heat.

Century II: “Music,” including topics on the loudness and softness of sound, equality and inequality of sound and articulation of sounds.

Century III: “Lines of which sounds move,” including topics on reflection of sounds, imitation of sounds, hindering and helping of hearing.

Century IV: “Clarification of liquids as well as the accelerating and maturation of fruits,” including making gold, acceleration of birth and the lasting of flame.

Century V: “Acceleration of germination,” including meliorating or making better fruits, sympathy and antipathy of plants and making herbs and plants medicinal.

Century VI: “Curiosities about fruits and plants,” including producing perfect plants without seed, the seasons of several plants and the lasting of plants.

Century VII: “Similarities and differences between plants and animals,” including the healing of wounds, clearness of the sea and north wind blowing, and of yawning.

Century VIII: “Medicine from nature,” including the glow-worm, sleep and the use of bathing and anointing.

Century IX: “Perceptions in bodies tending to natural divination,” including the causes of appetites in the stomach, flesh edible and inedible and of blows and bruises.

Century X: “Transmission and influx of virtues,” including the emission of spirits in vapor, secret virtues and properties and general sympathy of men’s spirits.

The topics are a curious and interesting look into early scientific thought. They depart quite a bit from today’s ideas and organization. Regardless, Bacon makes important movements toward the critical use of methodology in science and offers this information to others to make further advancements.

An example – his experimental process of observation of a bubble from Chapter I – may strike the reader as quite interesting:

“Bubbles are in the form of a hemisphere; air within, and a little skin of water without: And it seemeth somewhat strange, that the air should rise so swiftly, while it is in the water; and when it cometh to the top, should be staid by so weak a cover, as that of the bubble is.”

However, one may not be able to agree with, or understand, why one would do the following from Chapter VII:

“It hath been noted by the ancients, that it is dangerous to pick one’s ear while he yawneth. The cause is, for that in yawning, the inner parchment of the ear is extended by the drawing in of the spirit and breath; for in yawning and sighing both, the spirit is first strongly drawn in, and then strongly expelled.”

“Natural History” is filled with scientific observation of this sort, and if one has the patience to wade through this dense text, it makes for interesting insight into the mind of Bacon and those who lived in his time.

Title page of “New Atlantis, A Work Unfinished”

The next text within “Sylva Sylvarum” is a utopian novel set in the New World. Bacon advances his thoughts about how discovery and knowledge can lead to all of the finer qualities of mankind’s nature, which, according to Bacon, included generosity, enlightenment, dignity, splendor, piety and public spirit.

Following is a work that involves Bacon’s thoughts on the nature and length of life in regard to all of the variations that he observes, including everything from mankind, animals, plants and minerals. He posits ideas on what can heal or prolong life, such as elements, minerals, food, drink, practices and behaviors, and emotions. He then speculates on the nature of aging, death and of the spirit.

The final text in “Sylva Sylvarum” addresses properties of metals and minerals, including how they react to one another and their various behaviors when introduced to an element.

This particular copy of “Sylva Sylvarum” is from the George Fabyan Collection within the Rare Book and Special Collection Division. The Fabyan Collection includes many early editions of works of 17th-century English literature, as well as seminal works in science. The majority of the items in the collection focus on publications relating to cryptography, which is the science of creating a code within a document that only those with the key can interpret. It should not be surprising to learn that Bacon also made contributions in 1605 towards cryptography with his cipher based on steganography. To learn more on this topic, the Library of Congress offers a number of books in digital format on Baconian ciphers.

Just when one thinks Bacon’s influence couldn’t have been more far-reaching, we can also look to how Thomas Jefferson organized his library, which eventually became an early Library of Congress. Jefferson, a man of the Enlightenment, had adopted Bacon’s categorical system known as the “Advancement of Learning,” with major divisional topics that included memory, reason and imagination.

The Library of Congress offers a permanent exhibit of Thomas Jefferson’s books organized by Bacon’s system.

In addition, the Rare Book and Special Collection Division offers more information on the Jefferson Collection with a bibliography that includes commentary regarding the Bacon method of organization.

Portrait statue of Francis Bacon along the balustrade in Library of Congress Main Reading Room. Photo by Carol Highsmith, 2007. Prints and Photographs Division.

Bacon lived to the age of 65, nearly 400 years ago. This relatively short life by today’s standards still has an important and lasting impact on how life is lived in modern society today. He serves as an inspiration to us all to live a life of industry, aiming at enlightenment and advancement for mankind.

Resources at the Library of Congress via the Science, Technology and Business Division

Science Tracer Bullets Online: Cryptology

All things science

History of Science

From the Law Library

A blog post on Bacon and the Law

Exhibitions

Rome Reborn: The Vatican Library & Renaissance Culture

August 14, 2015

The Path a Book Takes

(The following story is featured in the July/August 2015 issue of the LCM, which you can read in it’s entirety here. The story was written by Susan Morris, assistant to the director for Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access.)

Follow the journey taken by each of the 300,000 books added to the Library’s collections annually.

Packages of books arrive at the loading dock in the Library’s James Madison Building.

Richard Yarnell reviews materials in the acquisitions mailroom where they are sorted by country of origin.

Between the time a book is published and a library user reads it, as many as a dozen Library staff members will have handled the volume. They will have made a series of crucial decisions about its acquisition for the collection, analyzed and described it in the Library of Congress Online Catalog and preserved and shelved it so it can be made accessible to readers.To track the path a book takes from arrival to the reading room, we will follow “Crónicas Cuauhtemenses” by Rodolfo Torres González, a volume received from the Mexican book dealer México Norte.

The book arrives at the loading dock in the Library’s James Madison Memorial Building on Capitol Hill. This is not the first stop the book has made in greater Washington. To ensure that books are not contaminated with chemical or biological substances, the packages have already been opened, inspected and resealed at an off-site mail-handling facility in suburban Maryland–like all mail that is delivered to the Library on Capitol Hill. The Library’s mail contractors load the packages of books into upright mail cages near the loading dock and push them to the acquisitions mail room on the basement level of the Madison Building, where Library staff sort them by country of origin.

The book travels to the Mexico, Central America, and Caribbean Section of the African, Latin American and Western European Division to receive acquisitions processing. An acquisitions specialist opens the package of books and verifies that the items received are ones the Library wanted and in good physical condition. The specialist evaluates each book to determine its cataloging priority–a crucial decision that determines how full a bibliographic description will eventually be created for the book. Next, a Library recommending officer determines that the title is within scope for the Library’s collections and confirms the cataloging priority. The acquisitions specialist prepares the invoice for payment and turns the book over to an acquisitions technician, who searches the Library’s Integrated Library System (ILS) to be certain it is not a duplicate of material already received.

The technician also searches the ILS for an initial bibliographic record and creates one if none exists. If no other cataloging data exist for the book, he inserts slips in its pages to show that it needs original cataloging–cataloging created “from scratch” by Library staff. The invoice from the vendor is forwarded to the section head who approves payment. The book is carried to the security marking and targeting station, where it receives a stamp on the top edge to indicate Library of Congress ownership and security targets are inserted, which will cause an alarm to sound if the book is removed from Library premises. The book is now under physical security control, inventory control and initial bibliographic control. It is placed on a book truck and delivered to staff members who have skill in cataloging Latin American material.

Deborah Vaden completes the call number and scans the barcode.

Barbara Tenenbaum checks to see if incoming titles should be included in the Handbook of Latin American Studies.

A senior cataloging specialist in the Mexico, Central America, and Caribbean Section completes the bibliographic control of the book. She reviews and expands the physical description of the book and determines which individuals and corporate entities were responsible for writing the content and publishing or sponsoring the finished book. She formulates authorized forms of names for the responsible parties and adds them to the bibliographic record in the ILS.

She also analyzes the content of the book in order to assign subject terms, using the standardized, controlled vocabulary in the Library of Congress Subject Headings. Very often, the cataloger creates new name or subject terms, in standardized forms, to provide access to cutting-edge research materials in the catalog. Finally, she assigns a classification number from the Library of Congress Classification System (LCC). Books about Mexican history will class between F1201 and F1392 in the LCC.

A cataloging technician adds information to the classification number to produce a complete call number. The call number serves as the physical address where the book will reside. All newly cataloged monographs in the general collections are shelved at the Library’s offsite facilities or in fixed location shelving on Capitol Hill in order to conserve space.

The LCC call number will always remain in the ILS bibliographic record for two reasons: other libraries that hold copies of the same book may want to use LCC call numbers as their books’ physical addresses; and the call number is hot-linked in the Library of Congress Online Catalog so that the Library’s end users can use the call number to launch online searches for other resources about the same subjects. “Crónicas Cuauhtemenses” received the call number F1391.C8835T67 2007, and it is stored in the Library’s offsite facility at Fort Meade, Maryland, where it can be retrieved and delivered to a user on Capitol Hill in a matter of hours.

The cataloged book is forwarded to the inspection shelves for the “Handbook of Latin American Studies” (HLAS) for review by the Library’s area specialist in Mexican culture. She inspects the book to determine whether it should be included in HLAS, the bibliography of publications about Latin America that has been edited at the Library of Congress for more than 70 years. The area specialist decides that this title should not receive an entry in this renowned reference tool. At this point, the book may also be considered for possible assignment to reference collections in the Library’s reading rooms.

Melanie Pollutta completes bibliographic control of incoming books and assigns the LC classification number.

“Cronicas Cuauhtemenses” has been cataloged, bound and deacidified.

Next, the Library takes steps to ensure the book will be available for generations to come. Like most books the Library receives from Latin America, “Crónicas Cuauhtemenses” is soft-covered. It will be sent to the Library’s Binding and Collections Care Division, which will ship it to the Library’s commercial bindery in Indiana. After it is hardbound, the book may be sent to the Library’s mass deacidification contractor near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to neutralize the wood-pulp acid in its pages. Deacidification prevents premature yellowing and extends the life of a book by 300 years or more.

The book has had a long journey from Mexico to Washington, D.C., with side trips to Indiana and Pennsylvania. When the cataloged, bound, and deacidified book is returned to the Library, it is now ready to be provided to the Library’s users in the Hispanic Reading Room, Main Reading Room or other reading rooms in one of the Library’s three buildings on Capitol Hill.

All photos by Shawn Miller

August 13, 2015

Freshening Our Perspectives

For more than a decade, the Library of Congress has been pleased to participate in an internship program sponsored by the Hispanic Association of Colleges & Universities, or HACU. Talented young Latino students work paid, 15-week internships with various Library divisions, getting a hands-on view of the options here and helping us get the work done with the kind of team vision that only a diversity of eyes can bring.

This would be a good situation from any angle; however, it is even better for the Library this year, because HACU announced today that the Library of Congress has won its Outstanding HACU Public Sector Partner Award for 2015.

“We are incredibly honored to be named HACU’s Outstanding Public Sector Partner,” said George Coulbourne, chief, internships and residencies in the Library’s National and International Outreach division. “HACU’s National Internship Program has 45 federal agencies participating, so we had some competition.”

Some HACU success stories the Library is proud to have shared in:

Lia Apodaca Kerwin, who worked in the Library’s Manuscript Division in 2005 preparing the papers of former U.S. Rep. Patsy Mink (D-HI) for use by researchers as a HACU intern, was hired as a reference librarian in the division, and later was promoted to a program specialist position in the Library’s Office of the Chief of Staff. Now she is a program specialist in the Library’s Office of Support Operations. She said HACU can help federal agencies such as the Library bring more Latino talent into their ranks. As for her own experience, “The opportunity of a HACU position at the Library of Congress was priceless.”

Eliamelisa Gonzalez, a HACU intern at the Library’s Office of Strategic Initiatives in 2010, worked on the Library’s Continuity of Operations (COOP) plan, which would allow the Library to maintain its operations in the event of an emergency that severely disrupted normal operations. She also performed new employee orientations regarding emergency preparedness, prepared training materials, updated a website and collaborated on a special project for the division chief. After working for OSI post-internship for several months, she was chosen in a competitive program by the Library’s Congressional Research Service, where she is now a human capital management specialist. “I am thankful for the HACU program, because it was the vehicle that allowed me the opportunity to come to D.C. and work at the Library,” Gonzalez said.

Kevin Pardinas, a HACU intern with the Library in 2008, now is a 5th-year associate attorney with the law firm of Quintairos, Prieto, Wood & Boyer, P.A. in Miami, Florida. He created a program manual for the Office of Strategic Initiatives that outlined ways for the Library to partner with universities and colleges. Pardinas said the most valuable aspect, for him, was “learning to work with high-level executives and administrators around the country,” which “honed my presentation skills” and made him “a much better public speaker and manager.”

Thomas Padilla, a HACU intern in 2011, now serves as a digital humanities librarian at Michigan State University. He held HACU internships at the National Archives and at the Library of Congress, and the Library offered him a fulltime job at the close of his internship. During his time at the Library he continued his graduate schooling, and he now has advanced degrees in History and in Library and Information Science. Having had “such a great experience with HACU, I looked for similar diversity-oriented support systems to help develop my skills as a librarian,” he said.

Ali Fazal, a HACU intern at the Library in 2012, now is manager of corporate business development for the mobile event app company DoubleDutch. At the Library, he worked on graphics, messaging and marketing for a program in its Office of Strategic Initiatives, the National Digital Stewardship Residency. He stayed on with the Library for seven months following his internship, then headed home to California to dig into the private sector. “Without HACU, I would have never have had the exposure … or the access to learn valuable on-the-job skills like graphic design and digital marketing, that have led me to success in my current career.”

Celia Rivas-Mendive, who worked for the EPA as a HACU Intern in the summer of 2006, now is a senior GAO analyst on the Natural Resources and the Environment team at the Government Accountability Office. She worked at the Library’s Congressional Research Service for four years following her HACU internship, via HACU’s Cooperative Education Program. “The fact that HACU took care of housing and travel logistics was critical for someone like me … someone who had never been to D.C. previously and who was moving from the West Coast. HACU changed my life by serving as a launching pad for my career in the federal government,” Rivas-Mendive said.

The Texas-based HACU, which aims to “champion Hispanic success in higher education,” started out in 1986 with 18 member institutions. Now it interacts with more than 450 colleges and universities in the U.S., Puerto Rico, Latin America and Spain. More than two-thirds of all Hispanic college students in the U.S. attend HACU member schools.

To celebrate these amazing young people—and the award they’ve made possible for the Library—today we offer this HACU haiku:

These talented kids

Diversify our outlooks —

The honor’s all ours.

August 12, 2015

Be Kind to Books Club

The following post is by Lucy Jakub, one of the 36 college students who participated in the Library of Congress 2015 Junior Fellows Summer Intern Program. Jakub is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in creative nonfiction at Columbia University. Her independent work in graphic design led her to her internship with the Library’s Conservation Division, making posters and other outreach materials that advocate care and respect for books and library collections.

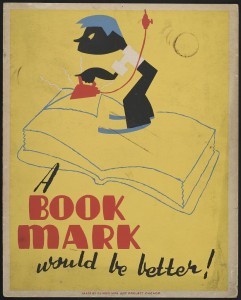

“A book mark would be better!” Poster by Arlington Gregg, between 1936 and 1940. Prints and Photographs Division.

“Don’t Dog-Ear. Use a Bookmark1″ Poster by Lucy Jakub, 2015.

My job this summer has been to design posters that advocate book preservation for schools and libraries. I was inspired by the work of Works Project Administration artist Arlington Gregg, whose poster series, in simple language and bold graphics, outlined the don’ts of book handling in the 1930s. I decided to make an updated series conveying the same messages in a fresh but reverential style. Each of my designs features a literary character from the public domain, recruited to teach kids how to take care of their books: Dracula cautions against exposing paper to the sun. Dorothy and the Wicked Witch of the West demonstrate water damage.

For artists scouring the public domain for free material, the Library’s digitized collections are a gold mine. Finding public domain images that are still instantly recognizable in today’s culture, however, can be a challenge. Even the greatest hits are sometimes fuzzy to contemporary children. There are sure to be some people asking why Dorothy’s shoe on my poster is silver and not red. When Disney filmed the “Wizard of Oz,” they changed L. Frank Baum’s silver shoes to ruby so they would sparkle in Technicolor. So though Disney cannot own a copyright on Baum’s character, they own the iconic ruby slippers.

In the interest of trying to make my posters a bit more contemporary, I decided to pursue a license for a character still under copyright. I went for my personal favorite: the Amazing Spider-man. The Library’s collections include the original art for Amazing Fantasy #15, Peter Parker’s comic debut. I wanted to put him on a poster telling kids not to touch their books with “sticky fingers.”

“If any super hero is suited to encourage children to read and care for books, it is Peter Parker, super-nerd and role model for us all,” I wrote to Marvel Comics.

Unfortunately, Marvel said no and wished me well. Disappointed but not to be deterred, I set my sights on Tarzan, whose disregard for cleanliness would make him a good fit for my poster: swings from a vine, half man half beast. I initially assumed Tarzan was in the public domain and free for artists to use because “Tarzan of the Apes” was published by Edgar Rice Burroughs in 1914, and its copyright has expired.

Though the book is in the public domain now, Burroughs incorporated himself in 1923. His name and all his major characters are trademarked and owned by Edgar Rice Burroughs Incorporated to this day.

Trademarks are a little different from copyrights. A trademark essentially serves as a symbol for a commodity. It must be renewed every 10 years but in theory can exist in perpetuity as long as it is continually renewed. A copyright, on the other hand, has an expiration date past which it cannot be owned by an individual or a corporation (right now, the term is 70 years after the death of the author).

Working with Edgar Rice Burroughs Inc. was a positive experience. They were excited about being part of my project and were accommodating to the Library’s limited resources. They were giving me Tarzan, but I was giving them something, too: a highly visible and positive platform for their character.

All five of the “Be Kind To Books Club” posters will soon be freely available to download and print from the Library’s website at www.loc.gov/preservation/.

August 11, 2015

Philosophers Habermas and Taylor to Share $1.5 Million Kluge Prize

The following post, written by Jason Steinhauer, was originally published on the blog Insights: Scholarly Work at the John W. Kluge Center.

Jürgen Habermas and Charles Taylor, two of the world’s most important philosophers, will share the prestigious $1.5 million John W. Kluge Prize for Achievement in the Study of Humanity awarded by the Library of Congress. The announcement was made today by Librarian of Congress James H. Billington. They are the ninth and tenth recipients of the award.

“Jürgen Habermas and Charles Taylor are brilliant philosophers and deeply engaged public intellectuals,” Billington said. “Emerging from different philosophical traditions, they converge in their ability to address contemporary problems with a penetrating understanding of individual and social formations. Highly regarded by other philosophers for their expertise, they are equally esteemed by the wider public for their willingness to provide philosophically informed political and moral perspectives. Through decades of grappling with humanity’s most profound and pressing concerns, their ability to bridge disciplinary and conceptual boundaries has redefined the role of public intellectual.”

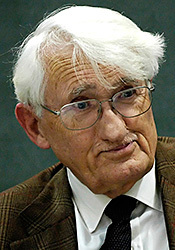

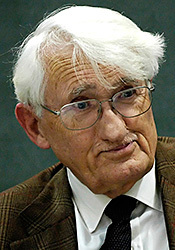

Jürgen Habermas

Jürgen Habermas

Jürgen Habermas is one the world’s most important living philosophers. Born in Düsseldorf, Germany in 1929, Habermas emerged as the most important German philosopher and socio-political theorist of the second half of the 20th century. His books, articles and essays number in the hundreds, and he has been widely read and translated into more than 40 languages, including Arabic, Catalan, Chinese, Danish, English, French, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish and Swedish. His major contributions encompass the fields of philosophy, social sciences, social theory, democratic theory, philosophy of religion, jurisprudence and historical and cultural analysis. He continues to publish actively.

“Jürgen Habermas is a scholar whose impact cannot be overestimated,” Billington said. “In both his magisterial works of theoretical analysis and his influential contributions to social criticism and public debate, he has repeatedly shown that Enlightenment values of justice and freedom, if transmitted through cultures of open communication and dialogue, can sustain social and political systems even through periods of significant transformation.”

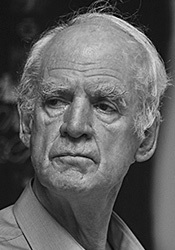

Charles Taylor

Charles Taylor. Photo credit: Makhanets.

Born in 1931 in Montreal, Canada, Charles Taylor, like Habermas, ranks among the world’s most original and wide-ranging philosophical minds. Educated at McGill University and as a Rhodes Scholar, at Oxford University, Taylor is best known for his contributions to political philosophy, the philosophy of social science, the history of philosophy and intellectual history, his work has received international acclaim and has influenced academia and the world at-large. Published in 20 languages, his writings link disparate academic disciplines and range from reflections on artificial intelligence to analyses of contemporary multicultural societies to the study of religion and what it means to live in a secular age.

“Charles Taylor is a philosopher of extraordinary eminence,” Billington said. “His writings reveal astonishing breadth and depth, ranging across subjects as diverse as metaphysics, modern culture, human conduct and behavior, modernization and the place of religion in a secular age. He writes with a lucidity that makes his work accessible to the non-specialist reader, ensuring that his contributions to our understanding of agency, freedom, spirituality and the relation between the natural sciences and the humanities will be of lasting import.”

About the Prize

The Kluge Prize

Endowed by philanthropist John W. Kluge, the Kluge Prize recognizes achievement in the range of disciplines not covered by the Nobel prizes, including history, philosophy, politics, anthropology, sociology, religion, criticism in the arts and humanities, and linguistics.

Administered by The John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress, ordinarily the Prize is a $1 million award. In 2015 the Kluge Prize is increased to $1.5 million in recognition of the Kluge Center’s 15th anniversary. Each awardee will receive half of the prize money.

Previous Kluge Prizes have been awarded to Polish philosopher Leszek Kolakowski (2003); historian Jaroslav Pelikan and philosopher Paul Ricoeur (2004); African-American historian John Hope Franklin and Chinese historian Yu Ying-shih (2006); historian Peter Lamont Brown and Indian historian Romila Thapar (2008); and Brazilian President and sociologist Fernando Henrique Cardoso (2012).

Learn more about this year’s recipients on our website: www.loc.gov/kluge/prize/ and on Twitter, #KlugePrize. The Prize will be conferred September 29th at a ceremony in Washington, D.C.

The following post, written by Jason Steinhauer, was orig...

The following post, written by Jason Steinhauer, was originally published on the blog Insights: Scholarly Work at the John W. Kluge Center.

Jürgen Habermas and Charles Taylor, two of the world’s most important philosophers, will share the prestigious $1.5 million John W. Kluge Prize for Achievement in the Study of Humanity awarded by the Library of Congress. The announcement was made today by Librarian of Congress James H. Billington. They are the ninth and tenth recipients of the award.

“Jürgen Habermas and Charles Taylor are brilliant philosophers and deeply engaged public intellectuals,” Billington said. “Emerging from different philosophical traditions, they converge in their ability to address contemporary problems with a penetrating understanding of individual and social formations. Highly regarded by other philosophers for their expertise, they are equally esteemed by the wider public for their willingness to provide philosophically informed political and moral perspectives. Through decades of grappling with humanity’s most profound and pressing concerns, their ability to bridge disciplinary and conceptual boundaries has redefined the role of public intellectual.”

Jürgen Habermas

Jürgen Habermas

Jürgen Habermas is one the world’s most important living philosophers. Born in Düsseldorf, Germany in 1929, Habermas emerged as the most important German philosopher and socio-political theorist of the second half of the 20th century. His books, articles and essays number in the hundreds, and he has been widely read and translated into more than 40 languages, including Arabic, Catalan, Chinese, Danish, English, French, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish and Swedish. His major contributions encompass the fields of philosophy, social sciences, social theory, democratic theory, philosophy of religion, jurisprudence and historical and cultural analysis. He continues to publish actively.

“Jürgen Habermas is a scholar whose impact cannot be overestimated,” Billington said. “In both his magisterial works of theoretical analysis and his influential contributions to social criticism and public debate, he has repeatedly shown that Enlightenment values of justice and freedom, if transmitted through cultures of open communication and dialogue, can sustain social and political systems even through periods of significant transformation.”

Charles Taylor

Charles Taylor. Photo credit: Makhanets.

Born in 1931 in Montreal, Canada, Charles Taylor, like Habermas, ranks among the world’s most original and wide-ranging philosophical minds. Educated at McGill University and as a Rhodes Scholar, at Oxford University, Taylor is best known for his contributions to political philosophy, the philosophy of social science, the history of philosophy and intellectual history, his work has received international acclaim and has influenced academia and the world at-large. Published in 20 languages, his writings link disparate academic disciplines and range from reflections on artificial intelligence to analyses of contemporary multicultural societies to the study of religion and what it means to live in a secular age.

“Charles Taylor is a philosopher of extraordinary eminence,” Billington said. “His writings reveal astonishing breadth and depth, ranging across subjects as diverse as metaphysics, modern culture, human conduct and behavior, modernization and the place of religion in a secular age. He writes with a lucidity that makes his work accessible to the non-specialist reader, ensuring that his contributions to our understanding of agency, freedom, spirituality and the relation between the natural sciences and the humanities will be of lasting import.”

About the Prize

The Kluge Prize

Endowed by philanthropist John W. Kluge, the Kluge Prize recognizes achievement in the range of disciplines not covered by the Nobel prizes, including history, philosophy, politics, anthropology, sociology, religion, criticism in the arts and humanities, and linguistics.

Administered by The John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress, ordinarily the Prize is a $1 million award. In 2015 the Kluge Prize is increased to $1.5 million in recognition of the Kluge Center’s 15th anniversary. Each awardee will receive half of the prize money.

Previous Kluge Prizes have been awarded to Polish philosopher Leszek Kolakowski (2003); historian Jaroslav Pelikan and philosopher Paul Ricoeur (2004); African-American historian John Hope Franklin and Chinese historian Yu Ying-shih (2006); historian Peter Lamont Brown and Indian historian Romila Thapar (2008); and Brazilian President and sociologist Fernando Henrique Cardoso (2012).

Learn more about this year’s recipients on our website: www.loc.gov/kluge/prize/ and on Twitter, #KlugePrize. The Prize will be conferred September 29th at a ceremony in Washington, D.C.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers