Library of Congress's Blog, page 143

August 7, 2015

Library in the News: July 2015 Edition

The Library’s announcement of Willie Nelson as the next recipient of the Gershwin Prize for Popular Music dominated the headlines in July, with more than 1,000 news stories running nationally and internationally.

“His voice, seemingly worn by time and burdened by experience even in his earliest recordings, attracted new audiences to country,” reported David Morgan for . “But Nelson also served as a major innovator – expanding the genre of country itself by exploring the language of blues, jazz, folk, rock and Latin, while also sparking a new sound: ‘outlaw country.”

Blog austin360 called Nelson the “patron saint of Austin” and offered up some interested stats on his career that paved the way for many distinctions, including the Gershwin Prize.

Outlets including Rolling Stone, USA Today, Hollywood Reporter, , and the Los Angeles Times, among many others, ran news of Nelson’s recognition.

A regular headline in the news has been the work being done out at the Library’s Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation. In July, Wired Magazine highlighted the facility’s work in preserving nitrate film, among other things.

“Arriving at the Library through a combination of private donations and official purchases, these nitrate films represent a small fraction of its 1.4 million movie, television, and video recordings,” wrote Bryan Gardiner. “Still, they’re without a doubt some of the oldest and most important.

Speaking of headlines, a story in playbill.com touted “Never-Before-Seen Pictures and Anecdotes from the Creation of ‘Little Shop of Horrors!'” – and the images were from the Library. The story by Logan Culwell featured a variety of images from the Library’s Howard Ashman Collection. Ashman was the musical’s lyricist, playwright and Broadway director.

According to the Culwell, this story was one of many to come offering “an unprecedented look behind the scenes at landmark musicals through writers’ handwritten drafts and other rarities archived within the Music Division of the Library of Congress.”

Broadwayworld.com also highlighted a musical story from the Library’s collections, featuring a Library blog post written about “The Sound of Music.” Through letters in the Oscar Hammerstein collection, the story (and the Library’s blog) reveal the story of Sister Gregory of Rosary College, who was instrumental in helping to create one of the most well-known and well-loved musicals of a generation.

In June, the Library opened a new exhibition on the Bay Psalm Book, which was featured in the July issue of Fine Books & Collections Magazine.

“The first thing visitors behold upon entering the exhibit space is a case containing two copies of the Bay Psalm Book (1640), the first book printed in colonial America, of which only eleven survive,” wrote Rebecca Rego Barry. “On the left sits the Library of Congress copy–worn and incomplete, but in its original binding. It is a remarkable pairing, and any bibliophile might be pleased to make the trip for it alone.”

Continuing to make news were educators participating in its Teaching With Primary Sources Summer Teacher Institutes. Regional outlets from Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Illinois, California and Washington, among others, announced local teachers who would be attending.

August 6, 2015

The Wandering Sculpture of a Thirsty POEt: A Look into Copyright Archives

The following is a post written by Gina Apone, one of 36 college students who spent the last two months working at the Library as part of the 2015 Junior Fellows Summer Intern Program. Apone currently attends Michigan State University pursuing a dual degree in Pre-Law and Professional Writing with a minor in Public Relations. Her internship in the Copyright Office has helped her gain a better understanding of and appreciation for how the Copyright Office operates and the role its divisions play in serving the public and Congress on both a local and international level. Of particular interest has been examining and learning about the different types of copyright claims for works of art like paintings, drawings, sculptures and designs that the office examines and registers each year.

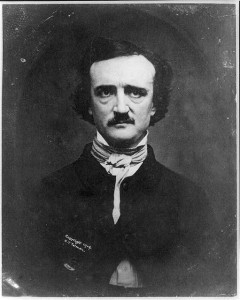

Edgar Allan Poe. 1904. Prints and Photographs Division.

As a Junior Fellow in the Copyright Office, I spent the summer examining copyright registration applications from the 1900s and uncovering various artifacts that have long been waiting in the archives of the U.S. Copyright Office. I repeatedly found myself surrounded by great people while being offered remarkable resources and unforgettable experiences.

A copyright deposit for a sculpture of Edgar Allan Poe, for example, might not sound very nerve-pinching or thought-provoking to many at a glance, but taking a second look could lead you to think otherwise. The specific photo of a bust that I came across, which is now stationed in the Edgar Allan Poe cottage in the Bronx in New York City, was submitted for Copyright registration on June 22, 1909, by Edmond T. Quinn, an established artist and sculptor from Philadelphia. His prominent work earned him gallery displays in various, well-regarded places like the Art Institute of Chicago and commendations by 1919 issues of the New York Times and the New York Tribune. He is best known for his bronze sculpture of “Edwin Booth as Hamlet” located in New York’s Gramercy Park.

In Quinn’s application are his handwritten notes describing the piece: “This is a bust portrait of Edgar Allan Poe. The poet is shown in his costume of about 1840…his head is inclined forward in a pensive attitude and the hair is somewhat disheveled.”

The Bronx Society of Arts and Sciences gave a plaster cast of Quinn’s sculpture to the Edgar Allan Poe Museum in Richmond, Virginia, in 1931, where it was on display as a part of the Poe shrine in the museum’s garden – that is, until it mysteriously vanished from its pedestal years later in 1987. Sometime later, the bust turned up at the Raven Inn, where police found it allegedly sitting at the bar with a mug of beer and a transcription of Poe’s poem, “The Spirits of the Dead.”

“And the mist upon the hill

Shadowy — shadowy — yet unbroken,

Is a symbol and a token —

How it hangs upon the trees,

A mystery of mysteries!”

Whether a comedic museum thief was exercising a peculiar sense of humor or the post-life Poe just got really thirsty, how and why the bust wandered off in such a puzzling, unexplainable fashion remains to be known. But the dark and haunting demeanor of the poet and his work only adds to the gripping curiousness of this account.

I remember learning about Poe and reading his famous work, like “The Fall of the House of Usher,” “The Cask of Amontillado” and “The Raven,” and being both fascinated and unnerved. Needless to say, as morbid as was the reputation he acquired with his tales of horror, Poe left a lasting impression on American literature and paved the way for writers during a time in which international copyright agreements were weak.

Copyright Deposit for “The Bust of Edgar Allan Poe,” c. 1908.

Library of Congress Copyright Office.

Unlike in Poe’s chilling tales and poems, however, you won’t be uncovering mysteries under the Library’s floorboards, but you will discover the record of works of all kinds by browsing the Copyright Office’s online catalog to your (Tell-Tale) heart’s desire. Available online are countless hidden gems dating from 1978 that are rich with history, culture and even a little mystery. (Prior to 1978, copyright records were created in analog form and housed in the Copyright Office. Once the Digitization and Public Access Project is complete, web-access to all pre-1978 records will be available.)

Working on this project and learning about pieces like this has shown me what a priceless resource the library is and how the country’s largest, ever-growing online archives can be utilized. Researching and uncovering the backstories behind these artifacts really puts into perspective the immense amounts of history that are right at my fingertips here at the Library of Congress, as well as showcases the many ways that the Copyright Office upholds its mission to administer the copyright law and to serve as a doorway to creativity and ingenuity. Will I ever be at a loss for information with the Copyright catalog so easily and readily accessible? As Poe would have put it – “nevermore” (“The Raven”).

Sources: “Poe’s Life: Who is Edgar Allan Poe?”, “15 Interesting Facts about Edgar Allan Poe” November 25, 2013, Kill/Adjectives Blog

August 5, 2015

Gifts to the Nation’s Library

(The following is a story featured in the July/August 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

This 1964 “Instrument of Gift” authorizes the Library’s acquisition of the papers of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access Directorate.

The Library of Congress acquires materials through many different streams. Copyright deposits, purchase of U.S. collections and exchange agreements with partners around the world, among other methods, substantially underpin the Library’s acquisitions.

One lesser-known method through which the Library acquires many of its special collections is through gifts. The Library’s acquisition of gifts is administered by the gift coordinator in the U.S./Anglo Division in consultation with Library curators and recommending officers. Not all gifts are accepted for inclusion in the Library’s collections. From single items to large collections, offers of gifts are evaluated for possible acquisition in accordance with the Library’s collection development policies.

The Library receives offers of materials in various formats such as manuscripts, films, photographs and other special collections. Library curators also actively solicit gifts from individuals and collectors in their respective fields. About 70 curators, recommending officers, and other Library officials are authorized to negotiate for gifts. For example, Verna Curtis of the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division offered the following justification for acquiring a gift of photographs by Vincent Cianni:

“Rollerbladers” in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, is part of photographer Vincent Cianni’s “We Skate

Hardcore” series, 1995. Prints and Photographs Division.

“This gift adds to the Library’s representation of the contemporary photographic practice of shooting in black-and-white and printing gelatin silver prints (now in decline) and serves as documentation of an urban culture in America. The photographs enrich the Library’s photography holdings by offering striking traditional prints which chronicle a community of in-line skaters Cianni met and followed in the Williamsburg, Brooklyn, neighborhood … during the 1990s.” The collection of 33 photographs recently came to the Library.

Once recommenders determine that a proposed gift meets the Library’s collection policies, they notify Gift Coordinator Peter L. Stark, who is authorized to obtain, pay for and arrange transportation for special collections that come to the Library of Congress. For many of the gifts, Stark works closely with the Library’s Office of the General Counsel, the recommenders and the donors to ensure that the agreements are clear and understood by all involved. Some gift acquisitions are more complicated than others.

The gift coordinator also arranges for the shipping of about 125 donations via Federal Express each year for the American Folklife Center, the Prints and Photographs Division and Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, to name a few.

Shipping large collections to the Library can create unusual challenges. Comprising more than 900 boxes, the papers of astronomer Carl Sagan were stored in a facility in Ithaca, New York, that was built into the side of a steep slope equipped with only a narrow stairway up to street level. The Sagan Collection was carried out of the facility one box at a time.

Marvin Hamlisch’s original manuscript for the song “Nobody Does It Better” is one of the many treasured items in the composer’s donated collection. Music Division.

Collections housed in various locations can also be complicated. A case in point is the recently acquired collection of composer Marvin Hamlisch.

“The collection was divided between the two coasts,” said Mark Eden Horowitz, a senior music specialist who works closely with the gift coordinator to recommend and acquire American musical theater collections for the Library. “Access to one location was hard to schedule and the collection includes rare and fragile items that required fine-arts shippers to pack. Through it all, the U.S./Anglo Division staff did the heavy lifting–both figuratively and literally.”

Often, a donor will arrange to send an initial shipment of material to the Library shortly after signing a gift agreement and then continue adding to the collection over a period of years. For example, the Manuscript Division recently received a five-box addition to the papers of conservative leader and National Review publisher William A. Rusher, whose original gift to the Library was made in 1989.

The exceedingly rare 1784 Abel Buell Map of the United States, now on display at the Library, was transported to the Library from New York City by special courier.

The U.S./Anglo Division acquires from 35 to 45 major special-format, non-book gifts per year, which each require a formal gift agreement signed by the donors and the Librarian of Congress. Stark writes approximately 250 letters per year acknowledging non-book gifts. The letters range from thanking donors for major collections to acknowledging the receipt of single gift items that “walk in” to collection divisions.

“From a single book to a large private collection, donations to the Library of Congress benefit the nation,” said Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access Director Beacher Wiggins.

Gift coordinator Peter Stark and Beth Davis-Brown, a section head in the Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access Directorate, contributed to this article.

July 31, 2015

Pics of the Week: Step Right Up, Folks!

Today we bring you a trio of images from this week’s display of items found in the Library’s collections by our Library of Congress Junior Fellows–36 interns from around the nation who dig through our collections during their 10-week stays and showcase their findings at summer’s end. Chosen each year through a competitive program, the fellows fan out across the Library, assisting with archiving, analytical tasks and other work that is valuable to us and fascinating for them.

To the right, Junior Fellow Gina Apone of Washington, Michigan, who attends Michigan State

Gina Apone and George Thuronyi

University, joins Copyright Office staffer George Thuronyi in displaying items found in Copyright’s files pertaining to a famous American circus of the 1890s, “The Great Wallace Shows.” Step right up, folks!

Below, you’ll see Junior Fellow Joseph Patton of LeRoy, New York, who attends SUNY at Buffalo and worked this summer with the Library’s Veterans History Project, overseeing a display about the VHP histories of two Navy veterans. Norman Duberstein, a WWII Navy fighter pilot, put in a collection rich with materials concerning the Pacific war, including photos of Duberstein and others in his squadron, creative works by members of that group and two of Duberstein’s own combat diaries. The late James Davis Mayhew, who served as a radioman aboard the battleship U.S.S. New Mexico, provided photos, letters including his own cartoons, and documents pertaining to the battles his ship engaged in. The 15-year-old VHP, which specializes in oral histories in which veterans of U.S. wars are interviewed about their service, expects to collect its 100,000th oral history this year.

Joseph Patton at the Junior Fellows VHP table

And this photo shows Junior Fellows Olivia Brum of Pottstown, Pennsylvania, who attends Alfred University, and Nicolas Kivi of Midland, Michigan, a student at the University of Tennessee, speaking with Associate Librarian for Library Services Mark Sweeney about a glass flute from the Library’s Dayton C. Miller Flute Collection, which they analyzed for preservation purposes. The Miller collection, which holds nearly 1,700 flutes from around the world, is housed in the Library’s Music Division.

Junior Fellows Olivia Brum and Nicolas Kivi describing their preservation analysis of a glass flute

July 30, 2015

Hypothesis of a Culture

April Rodriguez, one of 36 Library of Congress Junior Fellow Summer Interns, wrote the following post while working in the Library’s American Folklife Center. Rodriguez recently received a master’s degree in library information studies from the University of Wisconsin in Madison. She also has a background in sound engineering and film archiving, and she was able to expand those skillsets and knowledge while interning at the Library.

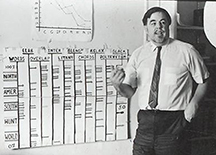

Alan Lomax discussing the choreometrics analysis process. Alan Lomax Collection, American Folklife Center.

What is culture? What elements of expression make each culture unique?

These were the major questions for folklorist Alan Lomax. In the late 1960s while taking courses from anthropologist Ray Birdwhistell, Lomax became inspired to build upon Birdwhistell’s study of body movement as a form of communication. Moving from analysis of song style, previously carried out in his cantometrics project, Lomax used a process that involved examining the “dynamics of body communication.”

This means of study by Lomax is known as choreometrics. The name is intuitive, a combination of the words choreography and metrics/measurement. Lomax defined choreometrics in “Choreometrics and Ethnographic Filmmaking” as “the measure of dance or dance as a measure of man.”

The choreometrics project developed into a large undertaking supported by grants, contributions of cultural dance footage from around the world and collaborations with movement analysis experts Irmgard Bartenieff and Forrestine Paulay.

In 2004 the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress acquired Alan Lomax’s materials. Lomax had worked for the Library of Congress between 1933 and 1942. My project at the American Folklife Center has been to advance the digitization work of the films used in the analysis and teaching of choreometrics in order to provide access. For me, it has been a journey of discovery.

Quantifying a Culture

Irmgard Bartenieff and Forrestine Paulay reviewing footage. Alan Lomax Collection, American Folklife Center.

Lomax felt that scholars lacked a systematic way of analyzing cultural experiences for the purpose of comparing them to their social and historical settings. One of Lomax’s ultimate goals was to determine how patterns in the body movements employed within a culture correlated with other cultural variables.

The choreometrics team hoped to identify cross-cultural variables by distinguishing patterns of movement and changes to those patterns throughout geographic locations. Methods for analyzing and notating human movement developed by Rudolf Laban were adapted for the study. Eventually a systematic means of coding dance was formulated by the team, which led to statistical analysis of the distribution of movement within a culture.

Variables for the coding process were refined and condensed from 139 to 65 variables, measured in four fields: body attitude and movement qualities, choreography, social organization and limb use, rhythm and form.

“In every culture we found some one document of movement style. This model seems to serve two main functions for all individuals: (1) Identification: It identifies the individual as a member of his culture who understands and is in tune with its communication systems. (2) Synchrony: It forms and molds together the dynamic qualities which make it possible for the members of a culture to act together in dance, work, movement, love-making, speech–in fact, in all their interactions.” ~ Alan Lomax

Choreometrics film to be inspected. Photo by April Rodriguez.

Visual Media

“Since dance is the most repetitious, synchronic of all expressive behaviors, it has turned out to be a kind of touchstone for human adaptation.” ~ Alan Lomax

Visual media provides both a means of capturing life and when shared through playback, a window to the world. Film allows researchers to split up the action and to examine it by frame. For the choreometrics project, dance provided consistent movement from which to conduct analysis, while film provided a carrier for dance to be seen and experienced.

When Lomax was asked by Filmmakers Newsletter about improving field recording he had this to say: “I argue that, in a very real sense, the field trip belongs more to the people studied or filmed than to the anthropologist or filmmaker. It is their life, their culture he is documenting. Without their cooperation, his efforts would come to nothing. Thus no documentary film expedition can be just a personal adventure – a big ego trip – because it may also be the first and only chance for some group of human beings to be put on record and to have their say on the big media.”

The choreometrics portion of the Alan Lomax collection consists of 3,565 film elements of 8mm, 16mm and 35mm. Prior to my arrival, priorities were laid out in a report regarding which series of film would be digitized first. To orchestrate this transfer process I needed to evaluate and update the inventory of each film element. As of this writing the film inventory is ready for use. What I have found challenging about sorting through the thousands of film elements is figuring out the connections between the series of film; there are duplicated materials, but finding the best version has been elusive.

Choreometics film being inspected. Photo by Nicole Saylor.

Digitization of the Lomax manuscripts pertaining to the choreometics project has begun. The documents include correspondence, indexes, contracts, written analysis and much more. Digitization of the choreometrics film will soon follow, so stay tuned as more of the collection becomes accessible to the public. Additionally the American Folklife Center is celebrating Alan Lomax’s 100th birthday throughout the year with events and activities. For more information visit www.loc.gov/folklife/lomax/lomaxcentennial.html.

Sources: Gardner, Robert. (Interviewer). (1974). Alan Lomax (Dance and Human History) [TV series]. “Screening Room”. Boston, Massachusetts: WCVB; Lomax, Alan . (1971, February). “Choreometrics and Ethnographic Filmmaking.” Filmmakers Newsletter, vol. 4, no. 4.

July 28, 2015

The Art of Acquisition

(The following is a feature story in the July/August 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. The story was written by Jennifer Gavin, a senior public affairs specialist in the Office of Communications. Joseph Puccio, the Library’s collection development officer, contributed to this story. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

The Library of Congress works daily to build a universal collection.

Blame Thomas Jefferson.

He’s the founding father (and ravenous reader) who convinced the U.S. Congress it needed not just his books on law and history to replace its 740-volume library–torched with the U.S. Capitol by the Redcoats in 1814–but all 6,487 of his volumes, in many languages and on many topics.

“There is, in fact, no subject to which a member of Congress may not have occasion to refer,” Jefferson argued–and the retired president won the day. His universalist, multi-lingual approach to book-collecting became the Library of Congress approach, and is a major reason the Library–with items in more than 470 languages–is a resource for the entire world.

From the acquisition of Jefferson’s personal library 200 years ago–which the Library celebrates this year–the Library has grown to 160.7 million items. This includes more than 38 million books and other print material, and nearly 123 million other items in other formats, including audio, manuscripts, maps, movies, sheet music and photographs.

How does the Library acquire all that knowledge, decide what to keep, and distribute the rest?

How Do Collections Come to the Library?

The Library gets its materials, which flow in at a rate averaging more than 15,000 items per working day, from four primary pipelines:

• Through gifts;

• Through the U.S. Copyright Office, which is part of the Library of Congress;

• Through purchases;

• Through exchanges with other libraries and other non- purchase arrangements.

The Library’s curators approach holders of prospective collections to let them, or their heirs, know of the Library’s interest in acquiring such collections.

Some of the Library’s most awe-inspiring treasures come in as part of larger, donated collections. For example, books of poems by William Blake and many other rare books came through donation by rare book collector Lessing Rosenwald.

The Library’s collection of the works, working papers and even the piano and typewriter used by George and Ira Gershwin were donated by their family. The heirs of Abraham Lincoln and of some of his cabinet members made gifts to the Library of papers and artifacts, including handwritten copies of his most famous speeches.

Since 1870–when Congress put the Copyright Office inside the Library–a deposit copy of each work copyrighted is made available to the Library for its collections. This gives the Library what Librarian of Congress James H. Billington likes to call the “mint record of American creativity.” Many of the most interesting items in the Library’s collections–from baseball cards to poetry, to Martin Luther King Jr.’s

“I Have a Dream” speech–came into the Library through copyright.

Purchases fill in another part of the picture. The majority of the Library’s budget is appropriated funding from Congress and a segment of that funding goes toward purchases of research materials. The Library also gets a boost from external supporters–such as the membership of the James Madison Council, the Library’s private-sector advisory group. Its members have been very generous in donating funding for Library acqusitions.

A mix of public and private money helped the Library buy, for $10 million, one of its top treasures, the Waldseemüller Map of 1507–the first document to include the name “America.” Private funding has helped the Library buy rare books, maps and many other collections.

Some items come to the Library through auctions. The Library has a process through which curators work closely with recommending officers to determine whether to bid on items.

Jennifer Baum-Sevec, who is involved in auctions as part of her work in the Library’s U.S./Anglo Division, said the Library typically works through agents, in part so it is not obvious it is a government agency doing the bidding (which might adversely affect the price). The Library, which under federal financial regulations cannot produce payment on the spot for such purchased items, also benefits by working with agents who are willing to wait for their own payment until the steps mandated by law have been undertaken.

Sometimes the Library decides to pass on an auction if it just gets too costly. “Determine your walk-away point–you have to go into it with that mindset,” Baum-Sevec said.

The Library also maintains collecting offices in parts of the world where getting materials is a bit more challenging. These are in Nairobi, Kenya; Cairo, Egypt; Islamabad, Pakistan; New Delhi, India; Jakarta, Indonesia; and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

From Intake to Shelf

Policy on what to collect has been established and is reviewed, as needed, by the Library’s Collections Development Office and its Collections Policy Committee, composed of key staff members throughout the Library.

The Library’s 200 recommending officers proactively identify items for acquisition and also select from other materials that have been received.

Designated staff in the Copyright Office, Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access Directorate and the Law Library of Congress also analyze the incoming materials and make selections. On average, about 12,000 items are selected daily from the 15,000 received.

Selected material must be cataloged, shelved–on about 838 miles of shelving in three buildings on Capitol Hill and several offsite storage facilities–and made available to researchers.

What about the Leftovers?

The Library of Congress does not collect everything it is offered, some of which is unsolicited.

Duplicates of books already in the collections and other books not meeting the Library’s collection criteria are placed in the Library’s Surplus Books unit for a time. These recent-issue books are available for donation to libraries or other nonprofit groups willing to cover the cost of moving them to new homes.

The World’s Largest Library

What this means is that the Library of Congress, with 21 reading rooms open to anyone 16 or older with a Library reader card, and online to anyone with internet access, is a veritable intellectual feast.

Thomas Jefferson probably didn’t anticipate that when he began amassing his personal library. But it’s not hard to imagine that he would be as proud of that as he was of penning the Declaration of Independence or helping found the University of Virginia.

He knew that knowledge is power.

July 23, 2015

Two Worlds Collide – Erich Leinsdorf Meets Janis Joplin

The following post has been written by Kevin McBrien, one of 36 college students participating in the Library of Congress 2015 Junior Fellows Summer Intern Program. McBrien graduated in May from California State University at Long Beach with a bachelor’s degree in music history and literature. He begins graduate school in the fall and hopes to become a teacher at the college level. Interning in the Library’s Music Division, he’s enjoyed valuable archival experience, particularly working with the music scores and photographs of musicians, orchestras and others.

Erich Leinsdorf and Janis Joplin at Tanglewood. Photo by Whitestone Photo, 1969. Music Division.

This summer, during my time working at the Library of Congress as part of the Junior Fellows Program, I have had the privilege of sorting and filing hundreds of photographs that are a part of the Music Iconography Collection. Housed in the Library’s Music Division, this collection contains publicity and press photographs of conductors, composers, opera singers, bands, orchestras, rock stars, concert halls and everything in between. Irving Lowens, who was employed as a music critic for the now-defunct Washington Star newspaper, donated many of these photos to the Library. Incidentally, he also worked in the Library’s Music Division from 1960 until 1978, serving as assistant head of what is now known as Reader Services.

Perhaps one of the more curious photos that I have encountered reveals a meeting in 1969 between two unlikely individuals: the blues rock singer Janis Joplin and the music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Erich Leinsdorf. Upon first glance I wondered, “Why would these two cultural icons, from seemingly opposite ends of the American art scene, have met together?” Curious, I conducted some research, and the results revealed a fascinating bridge between the worlds of classical and popular music.

In 1968, the late American composer Gunther Schuller suggested the idea for a “Contemporary Trends” concert series to be presented at Tanglewood, the summer music venue located in Lenox, Massachusetts. As head of Contemporary Music Activities at the time, he believed that it was “significant and necessary” to acknowledge the new developments that were occurring in popular music. Erich Leinsdorf, who was music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1962 to 1969, supported the idea with enthusiasm. Both Schuller and Leinsdorf had already established a Festival of Contemporary Music at Tanglewood, which programmed revolutionary works by George Crumb, Elliott Carter, Paul Fromm and other modern composers. However, the first series of popular music concerts in 1968 were rather conservative, featuring artists such as Judy Collins, the Modern Jazz Quartet, Ravi Shankar and The Association.

The next year, in the summer of 1969, the Contemporary Trends series better reflected the radically changing nature of American popular music. The lineup that summer included Iron Butterfly, Joni Mitchell, Ornette Coleman, Jefferson Airplane and The Who. Janis Joplin was chosen to headline the opening of the series, only weeks before her appearance at the legendary Woodstock Music Festival in August 1969.

On the evening of July 8, more than 7,000 people showed up to Tanglewood’s music shed to witness Joplin sing with her Kozmic Blues Band. (She sang on the first part of the program, and the second half featured the American rock band Orpheus). The concert series as a whole was controversial, with the locals complaining of the music’s ear-shattering volume and the rowdy juveniles that the artists attracted. One review from the Holyoke Transcript Telegram reported on the evening’s chaos: “Out of the darkness into a thunderous applause came the former Big Brother and the Holding Company’s lead singer, Miss Janis Joplin. After only ten minutes on stage, Miss Joplin left to complain about the state police and Shed officials who were trying to clear the aisles.” Regardless, Joplin’s performance was well received, and the singer even performed two encores for the adoring crowd.

Unfortunately, there is almost no information on the actual encounter between Janis Joplin and Erich Leinsdorf that is shown in the photo. However, Joplin’s “hippie” apparel, which was a trademark of her stage appearances, suggests that the two must have met backstage sometime during the singer’s performance on July 8, 1969. In any case, this photograph is truly intriguing, capturing a little-known meeting between two musical legends of the 20th century. If for only a moment, this brief encounter managed to bridge the gap between the classical and popular genres, uniting the two artists through a common passion – music. All in all, this photograph is just one of the many fascinating pictorial treasures that can be found in the Music Iconography Collection at the Library of Congress.

July 22, 2015

History You Could Really Sink Your Teeth Into

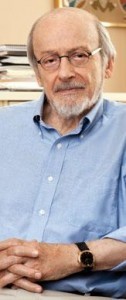

E.L. Doctorow, a giant of American letters who uplifted the genre of the historical novel, died yesterday at the age of 84. The author of “Ragtime,” “World’s Fair,” “Billy Bathgate,” “The March,” “Welcome to Hard Times” and “Andrew’s Brain,” among many other works of fiction, will be much missed.

Doctorow was the recipient of the 2014 Library of Congress Prize for

E.L. Doctorow

American Fiction, which recognizes lifetime achievement in American letters. Librarian of Congress James Billington dubbed him “our very own Charles Dickens, summoning a distinctly American place and time, channeling our myriad voices.”

Edgar Lawrence Doctorow, whose career spanned half a century, said as a child in the Bronx he “read everything I could get my hands on.” Early on, he started wondering what made the machinery of fiction tick – how to write it, in addition to enjoying it as a reader. “And so, I became a writer myself.”

Before he started work on what became a dozen novels, however, he studied philosophy and was involved in theater at college. He served in the Army in 1954 and 1955 then returned to the U.S. to work as a reader for the movie industry and later as an editor for the paperback publisher New American Library, where among other authors, he edited Ian Fleming and Ayn Rand.

Later, he was editor-in-chief at The Dial Press, where he published works by authors including James Baldwin and Norman Mailer. But in 1969, he left all that behind and became a fulltime writer.

The world was grateful for his career change: his work brought him the National Book Award for Fiction, the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction and the PEN/Faulkner Award. In addition to awards for his individual works, his body of work has been honored with the National Humanities Medal (1998), the New York Writers Hall of Fame (2012), the PEN/Saul Bellow Award for Achievement in American Fiction (2012) and the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters of the National Book Foundation (2013).

Doctorow received his Library of Congress award at last year’s Library of Congress National Book Festival. Here he is, at the festival, being interviewed about his work, and also speaking at the festival’s “Great Books to Great Movies” session, talking about what it’s like as an author to have your work adapted for the silver screen.

July 21, 2015

Curators’ Picks: The Art of Theatrical Design

The following is a feature from the May/June 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. Co-curators Daniel Boomhower and Walter Zvonchenko of the Music Division highlight items from the Library’s exhibition, “Grand Illusion: The Art of Theatrical Design.” This week is your last chance to stop by the Library to see what’s on display — the exhibition closes Saturday, July 25. You can also check out the exhibition online.

Performed before the imperial court of Leopold I in Vienna in 1668, “Il Pomo d’Oro” (The Golden Apple) featured an elaborate set designed by Ludovico Burnacini. “Baroque-era court shows were not just theater, they were manifestations of power,” said Zvonchenko. “The proscenium stage concealed elaborate contraptions, which allowed for fire and brimstone in the sky. It was not unusual for theaters that featured such special effects to burn down.” Music Division

“John Harkrider designed most of Florenz Ziegfeld’s shows, which were popular on Broadway during the first few first decades of the 20th century,” said Boomhower. “This sheet music cover–demure by Ziegfeld’s standards–presents Irving Berlin’s “Tell Me, Little Gypsy” from the Ziegfeld Follies of 1920.” Music Division

Set designers Elizabeth Montgomery and Peggy Clark, who collaborated under the name “Motley,” were “trailblazers as women became more involved in show production and management, as well as other theater occupations,” said Zvonchenko. Pictured here is their watercolor design for the Agnes DeMille Dance Theatre’s 1953 tour. Peggy Clark Collection, Music Division

4. Oliver Smith’s “My Fair Lady”

This watercolor and pen-and-ink set design depicts the scene in which Professor Henry Higgins discovers Eliza Doolittle selling flowers outside London’s Covent Garden opera house. “Smith was the first person hired for Lerner and Loewe’s 1956 production of ‘My Fair Lady,'” said Boomhower. “Before the director, before the cast–they knew who they wanted to design it.” Oliver Smith Collection, Music Division; Works of Oliver Smith © Rosaria Sinisi

5. Tony Walton’s “Grand Hotel”

“This is the 3-D model of Tony Walton’s stage set for the 1989 production of ‘Grand Hotel,’ which was designed without an orchestra pit out front for Broadway’s Martin Beck Theatre,” said Boomhower. “We wanted to exemplify the idea of spectacle. The scenic designer is a co-director. Design tells you how the show moves.” Tony Walton Collection, Music Division; reproduced by permission of Tony Walton

July 20, 2015

Inquiring Minds: An Interview With Author James McGrath Morris

James McGrath Morris is an author, columnist and radio show host. He writes primarily biographies and works of narrative nonfiction.

He discusses his newest book, “Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press,” tomorrow, July 21, at the Library. Read more about it here.

James McGrath Morris is an author, columnist and radio show host. He writes primarily biographies and works of narrative nonfiction.

He discusses his newest book, “Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press,” tomorrow, July 21, at the Library. Read more about it here.

Tell us about your new book “Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press.” What inspired you to write about Payne?

I had previously written several books about journalism and journalists. So when casting about for a project a few years ago I compiled a list of significant 20th century journalists using the Internet. Payne’s name showed up on the list. I don’t think I knew anything about her when I first spotted her name but within a few minutes of cruising the web I realized she was an important, but overlooked, figure in journalism history. It was such a good story that I presumed that someone was working on a biography. Twice before in my writing life I had embarked on projects only to learn that another writer was ahead of me. But when I discovered that her papers in two of the three institutions housing them had not yet been processed, I knew the story was mine to tell.

The state of her papers alone tells a story. The Library of Congress holds one third to one half of her papers. They are organized and accompanied by a finding aid. The papers elsewhere were, as I said, unprocessed at the time I started my work. They are well cared for in the hands of two major African American archives: The Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University and The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, a research unit of the New York City Public Library system. But the fact that her papers were unprocessed is a sharp reminder that these institutions, like many such places working to preserve African-American history, are short of funds and staff. Unless we find a way to better support these institutions, an enormously important portion of American history may not be accessible or, worse, preserved.

You call her the “first lady of the black press.” What made her so, in your mind? How did she compare to her contemporaries, and what made her such a pioneer?

Actually, I didn’t give her that moniker. While she was still alive, Payne was frequently hailed as the “first lady of the black press.” In the book, readers can see a photograph of her in front of an exhibition titled “The First Lady of the Black Press.”

The reason she earned the title was because of her prominence in the black press and the significant historic role she played. While she was the third African American to join the White House press corps in 1953, she contributed the most of the three in bringing issues of civil rights to national attention. She did this by asking questions of President Dwight D. Eisenhower about race issues of interest to her readers of the Chicago Defender, the premier nationally circulated black newspaper of the era. In doing so, she both educated the president and the press corps about issues they knew little about and caused the mainstream white media to pay attention. In short, by merely asking questions of the president, she triggered coverage of the issue – say racial discrimination in transportation or housing – by the national media.

Second, Payne did not confine her reporting to Washington. In fact, more often than not, she could be spotted on the front line of the civil rights movement in Montgomery, Alabama, or Little Rock, Arkansas, to mention two key sites of the struggle. Her reporting from these places, which carried considerable risk for a black female reporter, came prior to that of the white press and served to inform and activate her readers around the country.

Third, Payne presciently connected her coverage of the civil rights movement with the larger worldwide struggle for black freedom. So as early as 1955 Payne began traveling the world reporting from Asia and Africa on decolonization, apartheid and new black leadership rising in Africa.

Her work is credited with persuading many African Americans to take up the fight for civil rights. How so?

One of the great powers of journalism is its ability to put before large audiences information that might not otherwise reach them and to do so in a trustworthy fashion. When Payne covered the progress – or, often, the lack of progress – of civil rights legislation she was providing timely and important news to a national black readership that, in turn, could apply pressure to legislators. When she reported from the civil rights struggle in the South, she was helping garner national support for those leading the non-violent protest movement. Payne, in a sense, was an important part of the connective tissue that linked black readers with the civil rights struggle.

How was she also, perhaps, an inspiration to not only women of color but women in general in the industry?

Payne rose in a period in which women faced more than a glass ceiling, more like a closed door. Most professional careers were closed to women, even more so to black women. As a result Payne’s success was not only an inspiration to younger women, but she made an effort to smooth their paths. For instance, I met women who recalled Payne’s help in getting a job. But then, they told me, she would come by to visit and say, “Remember, you be quality” as a reminder that their success would open the door for other women in future years.

Tell me about the research you did at the Library in preparation for the book. What collections did you work with that you found most illuminating/interesting? Did you make any new connections or discoveries about the civil rights movement, women in journalism?

When it comes to working on a story connected to the civil rights movement, the Library is an indispensible partner. The collection of NAACP papers alone would make the manuscript room a mandatory visit.

I used Payne’s papers, as one would expect, but I also depended greatly on the remarkable staff of the Manuscript Division who always has advice to offer. I’m continually amazed at scholars who work anonymously in the manuscript room. They are only one question away from being told about a collection of papers that might play a key role in their research. In short, I always share the topic of my work with the staff, and over the past decades the members of this crew have never failed to reward me with an important lead.

Have you used the Library’s collections for your other works?

I have been using the Library’s collections for my writing since 1974. In fact, my relationship with the Library is old enough for me to be among those who once carried a stack pass. Now that I live many miles away in the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains near Santa Fe, New Mexico, the library remains a regular part of my life. Its online catalog and the wealth of material now also online are a treasure trove. I use the Chronicling America digital collection of newspapers almost as often as my kids check sports scores on their phones.

While I eventually do have to get on a plane to use most of the library’s collection it remains a research partner from afar.

Why do you think it’s valuable for the Library to preserve our history and culture and what do you think the public should know about using its collections and doing research here?

When I come to work at the Library of Congress I see hundreds, if not thousands, of tourists visiting the place as if it were a static memorial to the past. Despite the efforts of docents, I’m not sure that these visitors – or the public for that matter – understand how alive the place is. It does not merely preserve the past but shares it with everyone in a most remarkably democratic and inspiring fashion.

I have conducted research in libraries and archives all across the United States and overseas. The gatekeepers of these places, particularly in other countries, often make is clear that one’s use of their facilities is a privilege. Not so at the Library of Congress. For its staff, the public’s access is a right, not a privilege. No matter who you are, the Library issues an open invitation to come in and learn. From books to documents, from music to movies, America’s story is here.

In closing, any final thoughts on your book, Ethel Payne and her work during the civil rights era?

As a historian I worry greatly that younger people no longer know the story of the civil rights movement or, if they do, they know mostly stories of its central leaders. Yet the movement’s success was dependent on lesser-known individual such as Ethel Payne. As a result I think the version we provide students implies that change depends on great leaders, and they fail to grasp the important story that the power to change the world lies in each of us. If there is an injustice, one does need to await the next Martin Luther King. The truth and beauty of the movement is that its moral power lay in the fact that it was a grassroots revolution led by everyday people who rose to the challenge. Payne was among their ranks and hopefully her story will inspire others.

When she attended an almost all-white high school in South Side Chicago, she was permitted to contribute an article or two to the school paper but there was no question of permitting a black pupil to join the staff. This year the journalism room in the school has been renamed the Ethel Payne Journalism Center. I love the fact that now as students come into the room, some of them will take out their cell phones and Google her name. And, perhaps one of them will be inspired to follow in her path. For Ethel Lois Payne, a closed door was an invitation to struggle not to give in. We need more like her.

For further stories of the civil rights movement, check out the Library’s exhibition “The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom,” currently on view through Jan. 2, 2016.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers