Library of Congress's Blog, page 146

May 25, 2015

Pics of the Week: Auntie Rosa Remembered

Sheila McCauley Keys

Rosa Parks is known as a pioneer of the civil rights movement, a heroine for her courage of convictions. Yet, few knew the other side of her life – one spent as a devoted mother figure to her nieces and nephews. One such niece, Sheila McCauley Keys, was at the Library last week to remember her Auntie Rosa, who is also the subject of Keys’ new book “Our Auntie Rosa: The Family of Rosa Parks Remembers Her Life and Lessons.” Many of the family members were also on hand for the book talk.

Following her act of bravery on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955, Rosa Parks and her husband moved to Detroit in 1957, where Parks largely disappeared from public view. There, Parks reconnected with her only sibling, Sylvester McCauley, and her nieces and nephews. They were her only family.

“Aunt Rosa helped raise all of us, that’s just what family did,” Keys said.

When Parks passed away in 2005, the family largely mourned in public, unable to retreat from the public eye. Putting the book together was finally a way for them to do so by sharing the memories and lessons learned of the civil rights activist.

“She was kind, loving and tolerant,” said Keys. “She taught us that we were responsible for our own actions.”

She also instilled in her family the maxim of treating others as they would like to be treated, also known as the “Golden Rule.”

The Manuscript Division presented a display of items from the Rosa Parks Collection following the event.

Keys said that if her aunt were here today, Parks would appreciate being remembered and loved. However, she hoped that people would put that appreciation into perspective by doing the right thing, a creed that Parks lived by.

The Rosa Parks Collection is on loan to the Library from the Buffett Foundation for 10 years. Several items from the Rosa Parks collection are included in the Library’s ongoing major exhibition “The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom,” which is open through Jan. 2, 2016. Later this year, selected collection items will be accessible online.

Photos by Shawn Miller

May 21, 2015

Trending: Superheroes on Screen

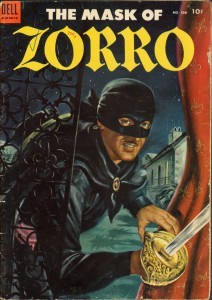

“The Mask of Zorro'”(1954), Serial and Government Publications Division.

Superheroes continue to captivate audiences nearly a century after their film debut.

America loves its superheroes (and villains). These beloved and delightfully despised characters continue to take center stage at the movies and on television.

“The Mark of Zorro” (United Artists, 1920), a silent film starring Douglas Fairbanks, was among the 10 motion pictures featuring superheroes that were released by American film studios between 1920 and 1940. By comparison, four such films came out in 2014, five in 2015, and a record nine are in production for 2016 release.

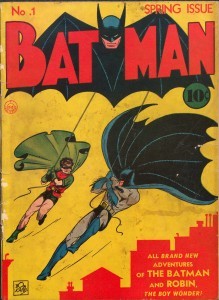

“Batman” (No. 1, 1940). Serial and Government Publications Division.

The popularity of “The Mark of Zorro” and its subsequent spin-offs, sequels and adaptations paved the way for a rise of the superhero genre in film and television. Comic-book artist Bob Kane has credited Zorro as part of the inspiration for the creation of his DC Comics superhero Batman, who debuted in print in 1940–the same year a film remake of the original Zorro was released, starring Tyrone Power. The film was directed by Rouben Mamoulian (1898-1987) whose papers are held by the Library of Congress. Housed in the Library, the film is among 650 titles that the Library has named to its National Film Registry since its inception in 1990.

Through the years, scores of films and television shows have featured popular masked and caped avengers, from Captain Marvel to Superman and from Spider-Man to the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Most recently, the pantheon of Marvel Comics characters has been brought to life, with films about the X-Men, Guardians of the Galaxy, Captain America and Thor grossing millions.

Television is even getting in on the action, with ABC’s “Marvel: Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.” and “Agent Carter” and Netflix original series, “Daredevil.”

The Library receives motion pictures and television broadcasts through copyright deposit. Included in the Library’s film and video collections are such films as the Superman series starring Christopher Reeve (1978-1987); “Batman” (1989) starring Michael Keaton, who also portrayed a faded film superhero in the Oscar-winning “Birdman” (2014); “The Dark Knight” (2008); “Iron Man” (2008) and several X-Men films, including animated and anime features. Also included in the Library’s collections are television episodes of “Smallville,” “Lois & Clark,” “The Incredible Hulk” and “Marvel: Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D,” among others.

(The following article was featured in the May/June 2015 issue of LCM, the Library of Congress Magazine. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

May 20, 2015

Pics of the Week: We Write the Songs

Natalie Merchant

Last week, the Library hosted the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) Foundation for its annual “We Write the Songs” concert, featuring the songwriters performing and telling the stories behind their own music. Taking the stage to perform some of their most notable music were Ne-Yo, Natalie Merchant (also formerly of 10,000 Maniacs), Donald Fagan of Steely Dan fame, Rupert Holmes and Rhymefest, who wrote “Glory,” the Oscar-winning song from the film “Selma.”

During the evening, the songwriters told some of the stories behind their music.

Ne-Yo

“Never had the guts to tell any of these girls how I felt about them,” said Ne-Yo of the girls who placed him in the friend zone. “Would write poems about them, the poems would stay in my little book and they would never see the light of day.”

Holmes, known for his hit “Escape (The Pina Colada Song)” talked about a last-minute change to the famous catch lyric of the song – imagine having Humphrey Bogart as the earworm instead of a delicious cocktail!

“The final lyric came to me in one hour, and there were a lot of critics who think I should have taken two hours,” he quipped.

Rupert Holmes

The Library is home to the ASCAP collection, which includes music manuscripts, printed music, lyrics (both published and unpublished), scrapbooks, correspondence and other personal, business, legal and financial documents, scrapbooks, and film, video and sound recordings.

Established in 1914, ASCAP is the first United States Performing Rights Organization (PRO), representing the world’s largest repertory of more than 10 million copyrighted musical works of every style and genre from 525,000 songwriter, composer and music-publisher members.

All photos by Shawn Miller

May 19, 2015

A Day at the Races

I’ve always been a sucker for a great hat. Before I came to work at the Library of Congress, I was a writer for a society magazine in Louisiana whose calling card was the hats we wore to cover local events. Needless to say, when given the opportunity to don a fashionable chapeau, I jump at the chance. This past Friday, I enjoyed a day at the races during Black-Eyed Susan Day – the precursor event to the Preakness Stakes in Baltimore, Maryland, at Pimlico Race Track – wearing a hat I actually made myself, out of placemats!

Kentucky Derby, Churchill Downs, Louisville, Ky. Photo by Caufield & Shook, 1937. Prints and Photographs Division.

Every year, the warmer weather heralds in the Triple Crown of Thoroughbred Racing in the United States. The series kicks off with the Kentucky Derby (which was held this year on May 2), followed by the Preakness (May 16) and culminating with the Belmont Stakes (set for June 6 this year). All three events are more than a century old.

On May 17, 1875, the first Kentucky Derby was held, with horse Aristides winning the inaugural race. Prominent Louisville citizen Col. M. Lewis Clark, Jr., built Churchill Downs and patterned the event after the English Classic, the Epsom Derby.

“The inaugural meeting of the Louisville Jockey Club opened today under more favorable auspices than had been hoped by the most sanguine of its managers. The attendance was upwards of 12,000, and the grandstand was thronged by a brilliant assemblage of ladies and gentlemen.

“Altogether today’s meeting was extraordinarily successful, the weather being everything that could be expected, the track in fine order and everything to indicate a satisfactory meeting.” — Nashville Union and American, May 18, 1875

Old members clubhouse at Pimlico – oldest building in American racing, dates back to 1870. May 15, 1965. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Preakness was first run May 27, 1873, with Survivor winning the purse. However, Pimlico racetrack opened in October 1870 with the Dinner Party Stakes won by the colt Preakness. According to its website, the Preakness marked its 140th anniversary this year (much like the Kentucky Derby), perhaps in honor of the horse itself and the very first race at Pimlico. The Library’s Prints and Photographs Online Catalog has several images of the racetrack.

“A notable feature of the day was that, with the exception of the first race, which was really no contest whatsoever, the favorites were badly defeated. In once instance, a horse se’ling lowest in the pools was the winner.” — Evening Star, May 28, 1873

The oldest of the three, the Belmont stakes debuted on June 19, 1867, at Jerome Park in New York with horse Ruthless taking home the win. According to history.com, Ruthless was also the very first filly to win one of the three historical races.

“DeCourcey and Ruthless now along, still were full of game, and footed homeward at a good bat. It was now a close and beautiful run … The noble pair lay with each other for 60 rods, DeCourcey still leading; but now the filly drew on him. As they reached the grand stand she had her nose at his saddle-girths. Yard by yard as she strode along she gained, and at the middle of the stand had him beaten, and got her head in front. Fifty yards were left to run, and the struggle was kept up to the finish, DeCourcey battling bravely, but Ruthless went over the score by half a length the winner.” — New York Tribune, June 20, 1867

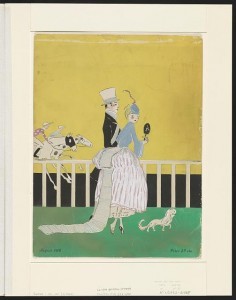

Couple at the races, by Ethel M’Clellan Plummer. 1916. Prints and Photographs Division.

Only two female thoroughbreds have captured the Belmont since (only 22 fillies have ever competed in the event.) Three have won the Kentucky Derby, and five have won the Preakness, the most recent being Rachel Alexandra in 2009.

As far as the history of wearing hats, we can thank our friends from across the pond, where hats and finery were de rigeur at races such as the Royal Ascot and Epsom. When Clark founded the Kentucky Derby, he also brought to it that fashionable European tradition.

According to the website of the Kentucky Derby, “What Colonel M. Lewis Clark Jr., envisioned was a racing environment that would feel comfortable and luxurious, an event that would remind people of European horse racing. For a well-to-do late 19th and early 20th century woman, a day at Churchill Downs, especially on Derby Day, was an opportunity to be seen in the latest of fashions.”

May 14, 2015

Have Exhibit, Will Travel

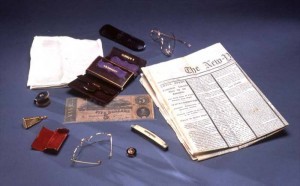

Contents of Abraham Lincoln’s pockets. April 14, 1865. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

True or false? Visiting Washington, D.C. is the only way to enjoy the collections of the Library of Congress. False. The Library offers a rich treasure trove of its collections. Not only that, it loans items to other institutions and agencies for their exhibitions, as well as offers other institutions and cultural organizations the opportunity to host touring exhibitions from the Library’s diverse exhibition program.

Just in time for baseball season, facsimile items from the Library’s vast baseball collections are on view at Nationals Stadium in D.C. and in Scranton, Pennsylvania, as part of the “Baseball Dreams: They Played the Game” exhibit. Featured in both displays are historic photographs of America’s favorite pastime.

Particularly relevant with the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War and Lincoln’s assassination are exhibitions at Fords Theatre and Henry Ford Museum in Michigan that mark the anniversary of the assassination. The Henry Ford Museum showcases facsimile lithographs from the Library’s collections, while Ford’s Theatre’s “Silent Witness: Artifacts of the Lincoln Assassination” has been loaned the contents of Lincoln’s pockets the night he was shot at the venue.

“Magna Carta: Enduring Legacy, 1215-2015.”

The Library collaborated with the American Bar Association to commemorate the 800th anniversary of the sealing of the Magna Carta in 1215 with a facsimile traveling exhibit that will be making the rounds until Feb. 7, 2016. Copies of Magna Carta-related rare documents and artifacts from the collections have been touring courthouses, law schools, universities and public libraries, including Buffalo’s federal courthouse, Utah State University’s Merrill-Cazier Library, University of Michigan Law School, Georgia Bar Center and Oklahoma City State Supreme Court.

If you’re ever in Los Angeles, California, you’ll want to visit the Library of Congress Ira Gershwin Gallery located in the Walt Disney Concert Hall. The gallery hosts Library exhibits highlighting the institutions performing arts collections. Currently on view is the “American Ballet Theatre: Touring the Globe for 75 Years” exhibit. Following its closing in August this year, “Grand Illusion: The Art of Theatrical Design” moves into the space and will be on view through February 2016.

For more information on the Library’s exhibitions, many of which are available on line, and the Library’s traveling exhibitions program, go here.

May 13, 2015

Collecting Comedy

(The following is an article from the May/June 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. Daniel Blazek, a recorded sound technician at the Library’s Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Preservation, wrote the story. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

Newspaper and Current Periodicals Reading Room.

Newspaper and Current Periodicals Reading Room.Groucho Marx perhaps best explains the importance of the Library’s comedy collections. In a television clip of his 1965 appearance on “The Tonight Show,” Marx discusses “a rather impressive” letter he received from then-Librarian of Congress L. Quincy Mumford requesting the comedian’s personal papers. Johnny Carson read the letter aloud.

Then Marx said, “I’m so pleased, having not finished public school, to find my letters perhaps lying next to the Gettysburg Address, I thought was quite an incongruity in addition to being extremely thrilling. I’m very proud of this thing.”

May 12, 2015

What’s Your Sign?

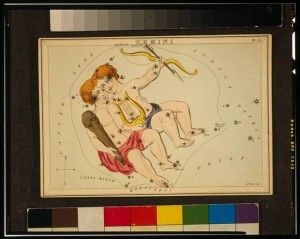

Gemini. Etching by Sidney Hall, 1825. Prints and Photographs Division.

For fun, members of my roller derby team figured out their astrological atlas, I suppose as a way to see how compatible each of us are and to understand our personality types for the purpose of working and competing together. The atlas is essentially a breakdown of your zodiac sign, including your rising sign, moon sign and sun sign. I admit this was very foreign to me – my knowledge of astrology only goes as far as the fact that I’m a Gemini and that my mother will occasionally read me my horoscope (usually only if it’s positive).

Americans have exhibited a bizarre fascination with demystifying their destinies. Gaining recognition in the late 1800s, the reputation of horoscopes has morphed from an ancient pseudo-science into a respectable discipline – featured almost daily in U.S. newspapers by the early 1900s.

This article from the Dec. 30, 1894 issue of The Salt Lake Herald reads like a veritable who’s who of “fashionable devotees” in high society.

“Mrs. William K. Vanderbilt is devoted to astronomy, with a decided leaning toward astrology. Perhaps considering the recent unpleasantness in her domestic circle she may be depending upon a combination of the planets to restore harmony after their period of hostile influences had passed.” Vanderbilt went on to divorce her husband, millionaire William Kissam Vanderbilt, in March 1895.

View from above of the zodiac in the marble floor of the Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building. 2007. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

Another article from The Sun (April 25, 1909) features an interview with an unnamed astrologer, who discusses clients, typical horoscopes and predictions for 1909. Apparently the astrologer takes issue with some female clients because they don’t want to tell their age, which is a requirement for accurate predictions.

Today, horoscopes and astrology are still as popular as ever. You don’t have to go too far to find a psychic offering palm reading or tarot cards. You can even get your horoscopes sent via text message.

Still, there has and will always be skeptics. I think this quote from The Evening Bulletin sums it up quite nicely:

“But it cannot be too often asserted that there is no truth in the art and never was. The sun and all the planets may be in conjunction and exert no more influence for good or evil over a baby than a passing milk wagon in the street.”

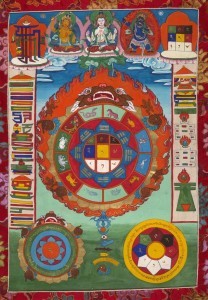

Divination chart from Tibet. Late 20th century. Asian Division.

You can explore the topic further and trace the horoscope craze through the Library’s collection of historical newspapers.

Many of the beautiful images adorning the halls of the Library feature astrological symbols–take note of the giant zodiac on the floor of the Great Hall. In fact, a sunny space in the southeast corner of the Thomas Jefferson Building, known as the Hall of Elements, is adorned with pastel-colored paintings representing the four elements and crowned by a disc in the domed ceiling that represents the sun. Although astrologers aren’t charting their future on its walls, the room does see researchers and scholars coming and going.

Of course, interest in astrology pre-dates our 19th century ancestors, with ancient civilizations and early explorers living and being guided by the stars themselves. The Library’s online exhibition, “World Treasures of the Library of Congress,” highlights a variety of historical foreign texts that focus on how mankind explained and ordered the universe.

May 11, 2015

Library in the News: April 2015 Edition

April headlines covered a wide range of stories about the Library of Congress.

The Library recently acquired a collection of rare Civil War stereographs from Robin Stanford, and 87-year-old Texas grandmother and avid collector.

“The images are rich and incredibly detailed,” wrote reporter Michael Scotto for New York 1.

Michael E. Ruane of The Washington Post spoke with Stanford.

“I’m so glad they’re here, because they will be available for everybody,” she told Ruane. “On the other hand, I’m going to miss them.”

The story of the Library’s acquisition was also featured on PBS Newshour and the Associated Press.

Other Civil War collections in the Library were also featured in a story from a Fox News affiliate in Roanoke, Va. Bob Grebe reported on Appomatox artifacts preserved at the institution, including original Matthew Brady photographs and Alfred and William Waud drawings.

In other collection news, the Library’s Dayton C. Miller flute collection made headlines thanks to a recent concert featuring the instruments.

And still making news was the Library’s acquisition of the Rosa Parks collection. Al Jazeera offered a glimpse into several of its items.

While many of these collection items are available digitally, the Library has other items on physical exhibit.

NPR highlighted the Library’s Music Division exhibition on theatrical design.

“Intrepid curators have created a small exhibition that lifts the curtain on how magic and spectacle are achieved on bare theater stages,” wrote reporter Susan Stamberg.

Offsite, the Washington Nationals baseball team is highlighting items from the Library’s vast baseball collections as part of an exhibit at Nationals Park. Urban Daddy featured it as part of a “What’s New” slideshow.

Dave Berry spoke of touring the Library itself and using its collections for research.

“At an overlook above the reading room, I was awestruck … Everyone was looking up and around. I was looking down … at three orderly rings of oak desks lit by lamps with green glass shades,” he wrote for the Tyler Morning Telegraph. “People on the floor seemed to be doing what people do in libraries … reading, studying, taking notes, exploring mounds of books and exploring the stacks. I wanted to be down there.”

In addition to exhibitions, tours and collections available to the public for research, the Library also hosts a variety of events. One such event is the annual poet laureate lecture to close out the spring literary season. This year, outgoing poet laureate Charles Wright invited former poet laureate Charles Simic to join him in conversation. The Washington Post covered the event.

“It made the star-power of Thursday evening’s presentation at the Library of Congress all the more impressive,” wrote Ron Charles. “There was the 20th U.S. poet laureate sitting on stage with the 15th U.S. poet laureate, their Pulitzer Prizes tucked discreetly behind them.”

The Library’s Capitol Hill campus isn’t the institution’s only branch. Several overseas offices are tasked with collecting and researching.

“The employees of the Library of Congress’s Overseas Offices don’t have just any job. They’re tasked with tracking down critical-yet-obscure materials from around the globe and bringing them stateside, all with the goal of making sure Congress–and anyone else who wants to use its library–has access to the world’s most current and comprehensive collection of information,” wrote Rachel Roubein for the National Journal.

“All of the LOC’s six overseas offices are in often unstable regions, but that’s by design,” reported Bridget Bowman for Roll Call. “The offices serve areas that may not have systems in place to archive and catalog books, publications, newspapers, maps, etc.”

And last, but certainly not least, the Library celebrated its 215th birthday on April 24. As Sadie Dingfelder of The Washington Post pointed out, it was also the birthday of Barbra Streisand, although the Library has a few on the singer and actress. Dingfelder went on to note some of the notable items in the instiution’s collection, such as the Gutenberg Bible, Abraham Lincoln’s scrapbook and the very first book printed in the U.S.

The Writer’s Almanac on NPR’s Morning Edition also mentioned the Library milestone.

May 7, 2015

The Sinking of the Lusitania

“The hour of two had struck and most of the first cabin passengers were just finishing luncheon. Suddenly at an estimated distance of about 1,000 yards from the ship there shone against the bright sea the conning tower of a submarine torpedo boat. Almost immediately there appeared a churning streak in the water and the trail of a death-dealing torpedo was marked. Passengers who saw the onrushing engine of destruction found no time for deep reflection. Instantly there was an explosion. Portions of the splintered hull of the steel vessel mounted upward over the waves to mark the stroke of the torpedo and fell again to mingle with still more debris sent aloft by the explosion of a second torpedo,” so reads “The Tragedy of the Lusitania” (1915), by Capt. Frederick D. Ellis.

Lusitania arriving in New York for first time, Sept. 13, 1907. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. Prints and Photographs Division.

On the afternoon of May 7, 1915, the German submarine U-20 torpedoed and sank the British cruise liner Lusitania traveling from New York to Liverpool, England. In a scant 18 minutes, the luxury liner with nearly 2,000 passengers sunk to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Ireland. Nearly 1,200 passengers perished; more than 100 were Americans, including millionaire Alfred Vanderbilt, writer Elbert Hubbard and theater producer Charles Frohman.

Only a couple of weeks before, the German Embassy published a warning in newspapers telling passengers that travel on Allied ships was “at their own risk,” including mentioning the Lusitania specifically. Germany had declared the waters around the United Kingdom a war zone. The fact that the Lusitania had been built with the ability to be converted into an armed merchant cruiser and that she was carrying war contraband was enough to incite Germany to attack.

According to a post from the Library’s Now See Hear! blog, within a month, the busy Victor Military band recorded “National Airs of the Allies,” a medley of anthems and national songs of France, Belgium, England and Russia. The sinking itself was soon memorialized in song in Charles McCarron and Nat Vincent’s “When the Lusitania Went Down,” published within weeks of the event. In February of 1916, Frederick Wheeler recorded “Wake Up, America,” which urged Americans to stand ready to join the fight.

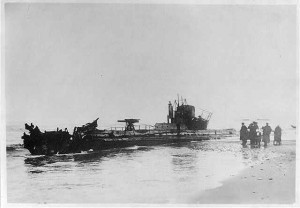

German submarine U20, said to be the one that sank the Lusitania. Between 1914 and 1919. Prints and Photographs Division.

While the sinking of the Lusitania was not the single largest factor contributing to the United States entering World War I two years later, it certainly solidified the public court of opinion against Germany. In addition, the deadly attack was also a turning point in modern warfare. Traditional mandates had called for warning commercial vessels before firing upon them. However, the introduction of the submarine posed a new threat of stealth attacks.

During the war, sections in newspapers captured the details and intensity of the fighting, introduced technological innovations to a curious and interested American public and documented the work and play of the home front. These pictorials were important tools for promoting U.S. propaganda and influenced how readers viewed world events. Images from the battlefields and dramatic coverage of casualties from the 1915 sinking of the Lusitania contributed to the U.S. decision to join the war.

The sinking itself has also been the topic of controversy, including the possibility that the Lusitania was deliberately put at risk in order to drag the U.S. into the war and that the ship was carrying undeclared war munitions in her cargo.

The Library has a wealth of material related to the sinking of the Lusitania and WWI, including a guide to historic newspaper articles, photographs and a compilation of digital collections.

May 6, 2015

A Whole New Ballgame

(The following is an article written by Mark Hartsell for The Gazette, the Library of Congress staff newsletter.)

The display at Nats Park explores baseball’s roots and D.C.’s baseball past. Courtesy of the Washington Nationals.

The Library of Congress is taking its collections out to the ballgame, reaching a new audience in a new venue.

The Washington Nationals in April opened an exhibition at Nationals Park that, through Library photos, explores baseball’s roots and celebrates the game’s traditions – especially in the nation’s capital.

“Baseball Americana from the Library of Congress” opened April 6 on the main concourse at the stadium’s home-plate entrance and continues indefinitely.

The exhibition features more than 30 oversized facsimiles of Library treasures covering more than two centuries of America’s pastime: the game’s origins, early competition, the men and women who played the game – Hall of Famers, members of Congress, soldiers – and those who cheered it on.

Library and Washington Nationals officials first discussed the idea two years ago while organizing an event to celebrate the Library’s acquisition of the papers of sports broadcaster Bob Wolff.

“There were several ideas discussed that arose from conversations with the librarian and the Development Office about ways we could work together with the Nationals that would be mutually beneficial,” Director of Communications Gayle Osterberg said. “Curators from several divisions brought some of the Library’s baseball treasures to share with Nationals representatives at a meeting in the summer of 2013.

An integrated Marine Corps team poses at Camp Lejeune in 1943. Prints and Photographs Division.

“Of course, when they saw the wonderful collections items and heard curators tell the history and stories, the notion of having a facsimile display at Nationals Park seemed like a good fit.”

Prints and Photographs, Manuscript, Music and Humanities and Social Sciences division curators worked with the Interpretive Programs Office and the Publishing Office’s Susan Reyburn – co-author of the 2009 Library publication “Baseball Americana” – to identify themes and items of interest to the Nationals.

The Library supplied the club with text and digital images, and the Nationals did the rest.

“So many people have contributed time and enthusiasm toward making it come together,” Osterberg said. “It will be a nice way to showcase the diversity of Library collections in a sort of unexpected location.”

The exhibition represents a new kind of outreach in another way.

“We’ve had traveling exhibitions go to many different places,” senior exhibit director Betsy Nahum-Miller said. “Something like this, where we do a display offsite that wasn’t an exhibit here, is a first.”

The Library preserves the world’s largest collection of baseball material: sheet music, baseball cards, photographs, films, newspaper clippings, broadcasts and recorded sound.

It holds the first film of a baseball game (Edison’s 1898 “The Ball Game”), the original copyrighted version of sports’ greatest hit (“Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” of course), the personal papers of pivotal figures (Branch Rickey, Jackie Robinson), perhaps the earliest baseball card (“Champions of America,” 1865) as well as the countless accounts of victory, defeat, historic teams and wretched losers found in the millions of newspaper pages of the institution’s collections.

“That you can find a box score here at the Library for almost any game I think is pretty remarkable,” Reyburn said.

“Baseball Americana from the Library of Congress” provides a taste of that to a new audience on its own turf – Nationals Park.

Curators divided the exhibition among seven themes: baseball roots, presidential pitches, congressional games, music, Washington baseball history, women in the game and – using images donated by servicemen to the Veterans History Project – baseball and the military.

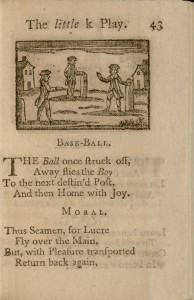

A 1787 printing of “A Little Pretty Pocket-Book” features verse and woodcut illustrations depicting outdoor activities for children – and provides the earliest-known printed mention of the game in America.

“A Little Pretty Pocket-Book” (1787) provides the earliest-known mention of

baseball printed in the United States. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

“The Ball once struck off/Away flies the Boy/ To the next destin’d Post/And then Home with Joy,” the author wrote in “Base-Ball.”

“The most fascinating strength of the Library’s collections is the Colonial material,” Reyburn said. “Nobody else has this material. It’s so rare.”

Many images explore the capital’s baseball past through scenes at Griffith Stadium, the ballpark that for more than 50 years served as home to the Washington Senators.

In the exhibition photos, Senators players raise the American League pennant in 1925, Babe Ruth slides into third, Hall of Famer Walter Johnson loosens up before taking the mound, Joe DiMaggio mingles at an All-Star Game and, on Ladies Day, fans visit with Bucky Harris, the player-manager who, at age 27, took over the Senators and led them to a World Series title.

A rare sheet of baseball cards dates to a still-earlier era of the game in D.C.

The Goodwin tobacco company in 1887 submitted the uncut sheet of photos of “Washington Base Ball Club” players to the Library as a copyright deposit. The company never distributed the cards in this form; the full sheets were only used to secure copyright and for advertising purposes.

“To produce large quantities efficiently, baseball cards are printed onto large sheets and later cut into individual cards,” said Phil Michel of the Prints and Photographs Division. “The cards are rarely seen in their uncut form on the original printing sheets, especially from the early years of production.”

The exhibit also highlights the D.C. roots of a baseball ritual: presidential pitches, a tradition inaugurated by William Howard Taft in Washington on opening day, 1910.

“It took time to become an annual ritual,” Reyburn said. “Most of them seemed to have been legitimate baseball fans. Woodrow Wilson truly was. A couple of them really did attend a lot of games.”

As defending American League champions, Washington Senators players raise the

pennant early in the 1925 season. Prints and Photographs Division.

Exhibition images show Taft, Wilson, Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt tossing first pitches from the stands – though not always successfully. Roosevelt’s throw, according to contemporary news accounts, struck a photographer’s camera, and the ball bounced into the hands of a nearby policeman.

Baseball and America, the exhibition notes, grew up together. The Library’s collections grew with them.

“I think people will be very surprised that the Library of Congress collects baseball and that this is important for the Library to collect,” Nahum-Miller said. “They’ll see that the Library collects all different kinds of things from American culture, including sports.”

The baseball exhibition is also available online.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers