Library of Congress's Blog, page 144

July 16, 2015

Look What I Discovered: Life as a Mary Wolfskill Trust Fund Intern

Today’s post has been wriiten by Logan Tapscott, one of 36 college students participating in the Library of Congress 2015 Junior Fellows Summer Intern Program. Tapscott is completing a modified dual degree through the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education: a master of arts degree in public history from Shippensburg University and a masters in library and information science from Clarion University of Pennsylvania. Interning in the Library’s Manuscript Division, Tapscott is interested in important archival and library skills such as processing, describing and referencing, as well as the Library’s African-American history collections with emphasis on the Civil War era and the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In the Manuscript Division Reading Room, every day is an adventure. Through the Junior Fellows Program and the generosity of the Mary Wolfskill Trust Fund Internship, I have an opportunity to work in the Manuscript Division this summer.

Established in 1897, the Manuscript Division holds approximately 60 million items in 11,500 separate collections that relate to American political, military and cultural history; yet, you never truly comprehend the value of the contents of each collection. Yes, finding aids assist both researchers and reference archivists to locate items, but examining the actual items in the folders or on the microfilm reels is an amazing feeling that never goes way. Each time that I receive a call slip or an online reference inquiry, I discover new collections and learn about interesting people or organizations. When answering reference inquiries, researchers ask a variety of questions, even about well-known historical figures such as Abraham Lincoln and Ralph Ellison.

Frederick Douglass, ca. 1850-1860. Prints and Photographs Division.

One example is when a patron asked whether Frederick Douglass delivered any speeches in Newark, N.J. The tireless Douglass delivered speeches throughout the New England and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States about the evils of slavery, but I was unaware of any speeches he may have given in New Jersey.

The first method I used to answer this question was to discover the division’s collection of Douglass’ papers, which contains correspondence, speeches and articles. After reviewing the finding aid, I was unable to find any speeches listed as given in Newark. Then, after realizing that his papers were digitized, I searched the digital Speech, Article and Book File series. Like the finding aid, the digital collection did not include any speeches from New Jersey.

Finally, I reviewed the published copies of the “Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One: Speeches, Debates and Interviews,” volumes 1-5. This compilation of Douglass’ writings was edited by John W. Blassingame – an esteemed and influential African-American historian – and published by Yale University Press in 1979. (Blassingame was the former chairman of the African American Studies Program at Yale University).

In these volumes, Blassingame chronicled Douglass’ speaking itinerary from 1847 until his death in 1895. In Volume 2, I discovered Douglass spoke in Newark, N.J. on back-to-back days on April 17 and 18 in 1849. By looking into this question, I discovered something different about the famous orator, abolitionist and vice presidential candidate.

Each day, I learn something new while working in the reading room, such as finding the location of a particular collection or how to assist readers accessing collections. So far, I don’t have a favorite collection, but I enjoy finding collections through the simple but large online catalog entries, published shelf lists and walking through the individual doors of the stacks. This is my adventure!

Sources: Nick Ravo, “John Blassingame, 59, Historian; Led Yale Black Studies,” New York Times, February 29, 2000, accessed June 30, 2015

July 15, 2015

Letters About Literature: Dear Mary Oliver

In this final installment of our Letters About Literature spotlight, we feature the Level 3 National Prize-winning letter of Aidan Kingwell of Illinois, who wrote to Mary Oliver about her poem “When Death Comes.” Kingwell’s poem also recently made the news.

Letters About Literature, a national reading and writing program that asks young people in grades 4 through 12 to write to an author (living or deceased) about how his or her book affected their lives, announced its 2015 winners in June. More than 50,000 young readers from across the country participated in this year’s initiative funded by a grant from the Library’s James Madison Council with additional support from the Library’s Center for the Book. Since 1997, more than a million students have participated.

National and honor winners were chosen from three competition levels: Level 1 (grades 4-6), Level 2 (grades 7-8) and Level 3 (grades 9-12). You can read all the winning letters here, including the winning letters from previous years.

Dear Mary,

I know it’s an unconventional subject for a letter; death. A fact of life that most of us endeavour to avoid, or at least ignore. But I, Mary – I have walked side-by-side with death all of my life.

I was thirteen the first time I read your poem, and at that time in my life there was a good chance that I would not see my fourteenth birthday. I had been depressed since age ten, but I had never received any treatment. My mind was very dark; I dove deeper and deeper into my own twisted thoughts with each passing moment. I was someone who was simultaneously terrified of dying, and yet obsessed with the very idea. I was also suicidal, which is a state of being that I cannot well describe, because there are not words that can describe such utter loss of hope, such bitterness and pain and unrelenting sorrow. I wanted to end my own life so badly that most days I could not find one single reason for living. It was not a cry for attention; it was a feeling of utter self-hatred. There is also no accurate way to describe the feeling of hating yourself and your life so much that you long to end it all. It is a feeling of being trapped, of being insane, of being hopeless. When you are suicidal, you are like a wild animal just barely being contained by a think human shell. Your soul is empty and your heart is blackened and dead. You have no straws left to grasp, no ladder to climb out of the abyss, and the only rope offered to help you scramble out is in the shape of a noose, and after weeks or months or years that noose begins to look very, very appealing.

So there I stood, face-to-face with death on a daily basis, wondering if each new day was the day that it would finally consume me. I was afraid of my own mind. I found no comfort in wooden crosses or the taste of bitter crackers, nor in the deluded words of psychiatrists. That eventual uncertainty – the uncertainty of the terror of my own death – haunted my footsteps as I walked from day to day, wearing it like a heavy, bitter cloak. The very idea of my own death was killing me.

The, one day, in my seventh-grade English class, I was presented with your poem. My teacher referred to it as “a dark poem with note of hope underlying,” but within it, I found so much more. Within it, I found new life. My mind opened up as I read your words; I was a frail but inspired butterfly clawing my way from a dark, putrid cocoon. The way you spoke, Mary; the way you talked about death, and how it sought to take all the bright coins from your purse, how it was an iceberg between your shoulder blades leeching the warm life out of your form. I could tell: you knew. You knew what it felt like to be owned by death’s shadow, in the same way that I was then. You had felt the same terror, the same all-consuming dread. But you were also strong. You faced death and said that it did not own you; you had looked into death’s dark eyes and said, “No, you cannot have me, I am not yet done here.” When you spoke of not wanting to have simply visited this world, my own world turned upside down. I began to think about how horrible it would be to have only been a visitor, in the way that you said; to not have made my mark on the world, to have only passed through with no real substance. I thought of a life lived entirely in absence of beauty and amazement, a life barren of love or excitement or laughter. I began to realize that that was what suicide would do to me. I saw that life was fast becoming my own. I saw killing myself would take me away before I even had the chance to make something of my life. Suicide would eliminate my pain, yes, but it also closed any doors of possibility that I might have still open to me; doors that may lead to happiness in my future.

I never would have imagined, Mary, that not killing myself would be one of the hardest decisions that I would ever have to make. But in the end, I made the choice, and I am still alive today. My life has not been full of joy; in fact, it has been dark, and hard, and at times I have even slipped back into death’s unrelenting grasp. But at those times, I have reminded myself of what I thought then – that I want to make something of my life, and that ending it would mean turning my back on all future possibilities, as well as the few pieces of happiness that I have managed to find in the present. At those dark times, Mary, I often also read your poem to myself – the poem that catalyzed my grand suicidal epiphany. I still struggle with this menace of the mental method, but now I have one thing that I did not have before, I have hope.

When Death Comes, Mary – and it will – I want to face it as an equal, and shake its hand as a friend, and accept it as an eventuality. You taught me that that is the only proper way to die. With your words you taught me that life cannot be lived in the shadow of death – that life must be a thing separate from death. And you taught me that when death comes, I should embrace it, but also that I should not welcome it before its time. You taught me, Mary, that there was nothing to be feared in death so long as my life was one well-lived.

“I do not want to end up having simply visited this world” . . .

And When Death Comes, Mary, I will tell it that you were my friend. Because you were. I will tell it that I am armed with your words, and it will bow its dark face in respect, and then, it will offer me its hand and lead me into whatever may or may not lay behind it. I will feel no fear, Mary – I no longer fear death and all its ways. I will know that I have beaten death down with your words and the inspiration that they gave me. I will know that I did not let it take me in any way but the one I wanted. And I will know that my life, no matter how twisted, corrupt, and fearful, was worth living.

So thank you, Mary. Thank you for wrenching death’s grip from my wrist. Thank you for showing me that the burden of my soul was not so dark. That there was still hope left in me.

Aidan Kingwell

July 13, 2015

Willie Nelson to Receive Gershwin Prize

Willie Nelson in performance in Austin, Texas, last year. Photo by Carol Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

(The following is an article featured in the Library of Congress staff newsletter, The Gazette, written by editor Mark Hartsell.)

So great is his impact on music, even folks who never bought a country album instantly recognize Willie Nelson: the headband, grizzled beard and long braids; the quavering, nasal voice and off-beat phrasing; the sound of Trigger, his nylon-stringed Martin guitar; the laid-back character out for a good time.

“Bring along your Cadillac, leave my old wreck behind,” Nelson sang. “If you’ve got the money, honey I’ve got the time.”

In a career that spans six decades, Nelson wrote country classics, helped remake the genre through the “outlaw” movement, scored more than 60 top-40 country or pop hits and brought new audiences to country music.

He also became a big star and an unlikely American icon – the long-haired Texan urging mamas not to let their babies grow up to be cowboys, the graying singer recalling all the girls he loved before, the celebrity famous enough to portray himself on “The Simpsons” and “Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me.”

On Thursday, the Library of Congress honored Nelson for his enduring impact on music, naming him the recipient of its Gershwin Prize for Popular Song. Nelson will receive the prize in Washington, D.C., in November. Details about the event – a luncheon and a musical performance are planned – will be announced later.

“Willie Nelson is a musical explorer, redrawing the boundaries of country music throughout his career,” Librarian of Congress James H. Billington said. “A master communicator, the sincerity and universally appealing message of his lyrics place him in a category of his own while still remaining grounded in his country-music roots. His achievements as a songwriter and performer are legendary.

“Like America itself, he has absorbed and assimilated diverse stylistic influences into his stories and songs. He has helped make country music one of the most universally beloved forms of American artistic expression.”

Pushing Musical Boundaries

Nelson continually expanded his musical language – and that of his audience and of country music – by incorporating a wide range of styles and influences: Western swing, jazz, traditional pop, blues, folk, rock and Latin.

He wrote country classics (“Crazy,” “Funny How Time Slips Away”), turned pop standards into big country hits (“Blue Skies,” “Mona Lisa”), made country hits with crossover appeal (“Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain,” “On the Road Again”) and scored big with pure pop tunes (“Always on My Mind,” “To All the Girls I’ve Loved Before”).

Nelson’s appealing persona, commercial success and critical appreciation also gave him a place in popular culture that transcended country – he was a big star, even outside the music industry.

Beginning in the late ’70s, he appeared as an actor in more than 40 films and TV shows – from lead roles in “Honeysuckle Rose” and “Red Headed Stranger” to appearances in “Miami Vice” and “Surfer, Dude.”

His music appeared in many more – even “Monday Night Football.”

“Turn out the lights, the party’s over,” commentator Don Meredith, lifting a line from a minor Nelson hit, would croon after a team made a victory-clinching play.

Nelson follows Paul Simon, Stevie Wonder, Paul McCartney, Burt Bacharach and Hal David, Carole King and Billy Joel as recipients of the prize – an honor bestowed on living artists whose lifetime achievements in popular song exemplify the standard of excellence associated with George and Ira Gershwin by promoting song as a vehicle of cultural understanding; entertaining and informing audiences; and inspiring new generations.

The librarian of Congress makes the selection in consultation with leading members of the music and entertainment industries and curators from the Music Division, American Folklife Center and Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division.

“It is an honor to be the next recipient of the Gershwin Prize,” Nelson said. “I appreciate it greatly.”

Voice from the Heartland

Nelson was born in 1933 to Ira and Myrle Nelson of Abbott, Texas. His parents had married very young – he was 16, she was 15 – and the union didn’t last long: Myrle left only months after Willie was born, and Ira later remarried and left, too.

So Willie and older sister Bobbie were raised by his blacksmith grandfather Will and grandmother Nancy, who picked cotton and gave music lessons.

Willie played guitar and wrote songs – as early as age 7 – and performed at church revivals and in local dance halls and honky-tonks.

After high school, Nelson joined the Air Force, spent two years at Baylor University and dropped out to pursue music. He lived here and there – San Antonio, Fort Worth, Vancouver, Houston – and sold encyclopedias and vacuum cleaners, worked as a disc jockey, taught Sunday school – all the while writing music and performing.

In 1960, he moved to Nashville, where he eventually found some success. Faron Young recorded his “Hello Walls” in 1961 and scored a No. 1 hit on the country charts. Soon after, Nelson played a demo for the husband of another performer. The singer was Patsy Cline and the song, “Crazy,” became a smash and a country-music standard.

Nelson began recording his own albums – his first contained three classics: “Crazy,” Hello Walls” and “Funny How Time Slips Away” – with only modest commercial success.

Country-Music Outlaw

In the early 1970s, he returned to Texas and became a key figure of the “outlaw” movement – performers who rebelled against the Nashville establishment that dictated which songs artists would sing and who would produce their albums.

The outlaws grew their hair long, wrote their own music and made their own records – a rootsy response to the formulaic, slick Nashville sound.

The albums Nelson released in that period – “Shotgun Willie,” “Red Headed Stranger,” “Stardust” “Wanted! The Outlaws,” “Waylon & Willie” – made him one of the most important figures in country music. “Red Headed Stranger” was inducted into the National Recording Registry at the Library in 2009.

He also established himself as a hitmaker with crossover appeal. Nelson scored more than 60 top-40 country hits across five decades and, beginning in the 1970s, a string of successes on pop charts, too: “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain,” “On the Road Again,” “Always on My Mind” and “To All the Girls I’ve Loved Before.”

He won seven Grammy Awards for his recordings and, in 1990, the Grammy Living Legend Award. He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1993 and the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2001.

July 10, 2015

Inquiring Minds: Anna Coleman Ladd and WWI Veterans

(The following is a story written by Megan Harris of the Veterans History Project and featured in the Library of Congress staff newsletter, The Gazette. )

Benjamin King portrays a soldier wearing a mask to cover a disfigurement. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Last month, eighth-graders Benjamin King, Maria Ellsworth and Cristina Escajadillo – all students at the Singapore American School – performed an original 10-minute play at the Library of Congress inspired by the institution’s collections and connections. Contemplating a distinctly somber topic — the mental and physical wounds wrought by World War I — the students highlighted the life and accomplishments of Anna Coleman Ladd, an artist and sculptor who created facial masks to help wounded soldiers cope with their injuries and reintegrate into civilian life after World War I.

Following their Library debut, the students performed as part of the Kenneth E. Behring National History Day Contest, held June 14-18 at the University of Maryland.

King, Ellsworth and Escajadillo first learned about Ladd’s mask-making through their social studies teacher, National History Day ambassador Matthew D. Elms.

Though they knew very little about World War I, Ladd’s story appealed to them as a nontraditional example of “leadership and legacy,” this year’s National History Day theme. The students engaged with Kluge fellow Tara Tappert after viewing her Jan. 22 lecture, sponsored by the Veterans History Project and the John W. Kluge Center and taped by C-SPAN, which featured Veterans History Project collections from World War I.

To contextualize Ladd’s activities, Tappert introduced the students to Melissa Walker, an art therapist with the National Intrepid Center of Excellence who incorporates mask-making into her work with recent veterans who have experienced traumatic brain injury. Walker aided the students in connecting Ladd’s work to present-day art therapy applications.

Featuring an original script based on archival letters and photographs, creative lighting and set design, and hand-painted papier-mache masks, the students’ performance conveyed not only the historical significance of Ladd’s work but also the individual cost of war.

Anna Coleman Ladd touches up a mask she made for a wounded soldier in 1918. Prints and Photographs Division.

Born in Philadelphia in 1878, Anna Coleman Ladd was a classically trained sculptress who in 1917 founded the American Red Cross Studio for Portrait Masks in Paris.

Modeled on the work done in the “Tin Noses Shop” established by British sculptor Francis Derwent Wood, Ladd created over 100 masks for veterans who had sustained serious facial disfigurements during the war.

As the performance made clear, Ladd’s gentle and humane treatment of her patients, known as “mutiles,” and the masks she made for them, eased the psychological pain caused by physical wounds.

For these veterans, Ladd’s masks affected not only their self-perception but also society’s reaction to them. As the students proclaimed in their play, “While some artists made art to change how people saw the world, [Ladd] made art that changed how the world saw people.”

A selection of photos featuring Ladd and her work with World War I veterans is available in the Library of Congress online catalog at www.loc.gov/photos/?q=anna+coleman+ladd .

July 9, 2015

Letters About Literature: Dear Walter Isaacson

We continue our spotlight of letters from the Letters About Literature initiative, a national reading and writing program that asks young people in grades 4 through 12 to write to an author (living or deceased) about how his or her book affected their lives. Winners were announced last week.

In this next installment, we highlight the Level 2 (grades 7-8) National Prize-winning letter from Gabriel Ferris of Maine, who wrote to Walter Isaacson, author of “Steve Jobs.”

Dear Walter Isaacson,

For the last few years I have been obsessively interested in computers, especially Macs. I picked up a copy of your book about Steve Jobs, excited by the thought that I might find a few technical nuggets that could broaden my horizons. I learned nothing about technology by reading your book but rather an unintended lesson on the delicate tight rope that often divides extreme business success and extreme failure in personal relationships.

Like so many highly successful people, Steve Jobs was driven by something that not many people have. This special something is called singular focus. As a result, Jobs had the ability to focus on only one thing and to tune out everything that didn’t align with his end goal. Throughout this book I found myself questioning if Steve’s high level of business success was worth the price he paid on a personal level.

Many a teenager in the twenty-first century would like nothing more than to be Steve Jobs, the founder of one of the largest, coolest businesses in the world! This was true about me until the day I flipped open the cover of your book. Reading about his rags to riches story that started in his garage was inspirational and entertaining. However, overshadowing all this was the mess he made of his personal life — and even some relationships in his business life. At times I felt bad for those around him. It was uncomfortable to look into his world and see the pain caused by his behavior.

Despite these feelings, I couldn’t put the book down. You brought me into his world in a way that no other book has. It inspired me. The reason your book inspired me was because it taught me that failing from taking risks in business (Project Computer Lisa) is not bad. Your writings actually taught me that risk taking as well as failing can be good to the extent that you learn from your mistakes. This concept that failing can be ultimately productive played out many times in your story of Steve’s life.

Additionally, I was also inspired by examples of what I don’t want to be. It showed me that true singular focus can be very expensive in human relationships. Steve Jobs was so focused on his “singular goal” that he would ignore some of the most important things in his life — family and friends. Steve went so far as not seeing his girlfriend who he had a daughter with. When reading this part of your book I had to go back and reread this section because it seemed so surreal to me that a person could actually say no to seeing his own daughter or being part of her life. When putting myself in Steve’s position I could never imagine doing something as extreme as this. I found myself asking if this behavior was normal for Silicon Valley executives? Is the value of family life typically lost in the pursuit of the Silicon Valley Dream?

This same singular focus that interfered with family life also contributed to failed relationships at work. Steve Jobs had a single vision, and he wasn’t generally open to deviations. As I read his story, I realized that he wasn’t anyone I’d want to work for! His coworkers complained that he was too determined and in fact acted like an unpredictable small child when he didn’t get what he wanted. A perfect example of this was when Steve worked at Atari. His inability to work with others had him restricted to work hours when no one else was around. When I first read the chapter about his days at Atari, I didn’t really understand how someone could be too determined, too driven and too rigid. It was not until many chapters later that I started to realize that the same factors that played into his extreme success were the very factors that contributed to his personal human failure in almost all relationships. I remember a point where I stopped reading to try to pull my thoughts together as my vision of what I thought was a model life story was falling apart.

It’s only been a month or so since I finished your book on Steve Jobs. I still think about it a few times a week. You changed my life in a way I didn’t anticipate. I’m conflicted about the price of success. At 13 years old, I haven’t read a lot of biographies that detail the personal lives of super successful people. I understand that an underlying theme for the super successful is being fully dedicated to the goal at hand. Steve Job’s behavior reminds me of the old saying that “nothing succeeds like excess.” Is excess a requirement for extreme success? Your story leaves me wondering if this is the case — and struggling with the balance between still wanting to do something great while still being someone great. Consequently, your story created more questions in my life than it answered.

Gabriel Ferris

More than 50,000 young readers from across the country participated in this year’s initiative funded by a grant from the Library’s James Madison Council with additional support from the Library’s Center for the Book. Since 1997, more than a million students have participated. You can read all the winning letters here, including the winning letters from previous years.

July 7, 2015

Library in the News: June 2015 Edition

In June, the Library of Congress issued two major announcements that made headlines nationwide: the appointment of a new Poet Laureate and the retirement of the current Librarian of Congress.

After nearly three decades of service, Librarian of Congress James H. Billington announced his retirement effective January 2016.

Speaker of the House John Boehner, Democrat House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell were among many members of Congress who expressed appreciation for Billington and his work.

“No one is held is higher esteem on Capitol Hill than James H. Billington,” said Boehner. “As kind as he is brilliant, Dr. Billington has revolutionized the Library of Congress and the American people’s relationship with it.”

“Dr. James Hadley Billington’s unwavering commitment to scholarship helped steer the Library of Congress into the 21st century,” added Pelosi. “For Dr. Billington, the pursuit of knowledge has been a life-long endeavor that is both integral to enriching our nation’s democracy and engaging with people across the nation and around the world.”

“Billington was a scholar and an intellectual, and he positioned the library not just as a repository of information but also as a locus of debate and cultural exchange,” wrote Philip Kennicott for The Washington Post.

“Since Billington joined the library in 1987, the collection has nearly doubled in size to 160 million items,” said Brett Zongker in his story for the Associated Press. “Billington is credited with leading the library into the digital age, making research materials and legislative databases available online.”

While news of Billington’s successor will have to wait until next January, news of the appointment of Juan Felipe Herrera as the nation’s next poet laureate was received with much acclaim.

“Mr. Herrera is a poet you’d like to hear declaim from the National Mall,” wrote Dwight Garner for the New York Times. “When he is on he is really on, in touch with his audience and in touch with democratic gifts. His senses are open toward the world and his bearing on the page is noble and entrancingly weird.”

“I’m here to encourage others to speak,” Herrera told The Washington Post. “To speak out and speak up and write with their voices and their family stories and their sense of humor and their deep concerns and their way of speaking their own languages. I want to encourage people to do that with this amazing medium called poetry.”

Herrera told the that he hopes to encourage more young Latino students to write and read and benefit from the Library of Congress’ resources.

In other news, the Library began welcoming educators participating in its Teaching With Primary Sources Summer Teacher Institutes. Regional outlets from New York, Michigan, Arizona and Mississippi, among others, announced local teachers who would be attending.

July 1, 2015

Rare Book of the Month: Redouté’s Royal Roses

(The following is a guest blog post written by Elizabeth Gettins, Library of Congress digital library specialist.)

Frontispiece portrait of Pierre-Joseph Redouté, (1759-1840) from “Les Roses.” Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

When Pierre-Joseph Redouté put together his three-installment publication (1817-1824) “Les Roses” in Paris, he created a thing of great beauty as well as a scientific compendium on the botany of roses. Commissioned by the Empress Josephine, this work is a reflection of what was considered fashionable and visually appealing in royal circles at the time. Redouté was even the court artist for Marie Antoinette and other royalty.

Making use of an understanding of botany and a painterly eye, Redouté created a work that chronicles an interesting time in history – when art and science intersected to produce a work that was both educational and attractive.

Dutch in origin, Redouté (1759-1840) was a product of the Flemish school of still-life painting. This style required an eye trained and focused on depicting botanicals in what was considered their most true and beautiful form. Redouté conferred with the most learned of botanists of his day to accurately depict the various components of the rose. Botanical illustration strove to document in a photographic manner but through the lens of romantic notion. The results record gentle beauty in great detail.

Redouté used Empress Josephine’s own garden at Malmaison for inspiration to create “Les Roses,” and the result is more than 250 beautiful illustrations of a variety of roses. The Empress was an avid gardener and wished to transform Malmaison into a sanctuary for study of the rose, along with other flowering plants. She purchased countless rose varieties and contributed to the popularity of the rose, as well as to the propagation of varieties of roses that make up many roses gardens to this day.

Rose illustration from “Les Roses”: Rosa Gallica Officinalis. Rosier de Provins ordinaire. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

When Redouté was finished with his rose watercolors, he had the paintings transferred into engravings. In all, 170 prints were produced, accompanied by the commentary of botanist Antoine-Claude Thory, who attempted to describe the genus and variety of all roses contained in the work.

“Les Roses” is still referenced to identify-lesser known antique varieties of roses, as it is nearly exhaustive in its catalogue. However, “Les Roses” is primarily lauded as one of the masterpieces of botanical illustration. The beauty, delicacy and accuracy of each flower portrayed is unsurpassed by any other botanical illustrator.

“Les Roses” was quite expensive to produce and because of this, not many copies were made. Only the very wealthy would have the means to acquire a copy of the work. Thanks to the collector Lessing J. Rosenwald, the Library of Congress has a copy of this incredible work to offer. “Les Roses” has been fully digitized and is available for all to appreciate. Like the rose itself, it is not only for the eye of aristocracy but is available to all who wish to behold the visions of beauty that Redouté created.

Rose illustration for “Les Roses”: Rosa Sulfurea. Rosier jaune de souffre. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

The Library offers several resources related to botany and botany illustration through the Science, Technology and Business Division, including selected Internet resources on the topic of botany, Economic Botany: Useful Plants and Products, Plant Exploration and Introduction and this video on plant hunters.

The Library’s collection of Garden and Forest: A Journal of Horticulture, Landscape Art, and Forestry (1888-1897) offers digital copies of a weekly periodical. In total, the full 10-volume run of Garden and Forest contains approximately 8,400 pages, including more than 1,000 illustrations and 2,000 pages of advertisements.

To preview a listing of some the Library’s other images of botanical illustration, search for “botanical illustration.” Many of the supplied images are from the Prints and Photographs Division and are of individual prints or were captured from pages of books on the topic of botany.

(Every month, the Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division will highlight a unique book from its collections, and the Library of Congress blog will take an in-depth look at the historical volume. Make sure to check back again next month!)

June 30, 2015

Letters About Literature: Dear Wendelin Van Draanen

Letters About Literature, a national reading and writing program that asks young people in grades 4 through 12 to write to an author (living or deceased) about how his or her book affected their lives, announced its 2015 winners today.

More than 50,000 young readers from across the country participated in this year’s initiative funded by a grant from the Library’s James Madison Council with additional support from the Library’s Center for the Book. Since 1997, more than a million students have participated.

The top letters in each competition level for each state were chosen. Then, national and national honor winners were chosen from each of the three competition levels: Level 1 (grades 4-6), Level 2 (grades 7-8) and Level 3 (grades 9-12). For the next few weeks, we’ll post some of the winning letters. This year’s winners are from all parts of the country and wrote to authors as diverse as Sandra Pinkney, Walter Isaacson, Elie Wiesel and Art Spiegelman.

The following is the Level 1 national prize-winning letter written by Gerel Sanzhikov of New Jersey to Wendelin Van Draanen, author of “The Running Dream.”

Dear Wendelin Van Draanen,

I have never lost a leg. I was not born with cerebral palsy. I do not use a wheelchair. I do not have speech problems. But I have lost the one thing I loved the most. My family is made up of my dad, my two grandmothers, my sister, and me. Where is my mom? Look above you. She has landed among the stars.

My mom fought for two years in the battle of cancer. We lost her in September of 2012. I remember when my mom was first diagnosed; she started losing her hair a couple strands at a time. Next thing you know, she was almost bald. Jessica and my mom both lost something important. Out of nowhere, Jessica lost her leg in a car accident. My mom lost most of her hair. They both lost some of their pride. Life is funny, you know? Like at first, your life is going perfect and you have everything you could wish for, and just like that . . . it’s gone. Everything is ripped apart. Simply just . . . gone.

I was heartbroken. My mom looked miserable. I could not stand seeing her suffer like that. She needed countless doses of medicine and weekly chemo therapies. She went through the same cycle for two years. But on a beautiful sunny afternoon, she grew wings. She was an angel in heaven and she was flying in the sky. I was downcast but also happy she was free from suffering. Before I read your book, I never thought I could be joyful again.

But then I read it. I have realized that I am not the only one who has this problem. As I was reading “The Running Dream,” I saw how difficult it was for Jessica to adjust to such a dramatic change and I could relate. Jessica needed to use a prosthetic leg and learn how to walk with crutches. I needed to embrace the fact that my mom was in a better place. Reading your book gave me a different perspective on things. I thought I would never be happy again, but when I read how Jessica got her running leg and practiced running little by little, I realized that I could jump back on track too. When her teacher showed her the YouTube video of the running amputee, she thought, “Maybe I can run again.” And so did I.

I could not put your book down as I was reading. One of the reasons I fell in love with it is because it is so inspiring. You would never think that a girl like Jessica – popular, pretty, and perfect – would become friends with a girl like Rosa – who had cerebral palsy and used a wheelchair. I love how your novel showed that anything is possible if you believe and try. Jessica and Rosa developed a bond that will never break.

Your book moved me in a way that no book has ever done before – it gave me hope. By reading “The Running Dream,” I have learned many things. I have always wondered why I was never happy, besides the fact that my mom had passed. But then it hit me. If I spent the rest of my life focusing on all the negative elements, I would never be able to enjoy all the little things that make up a good life.

Your book also taught me that when life knocks you down, you just need to pick yourself up and keep on moving. When Jessica lost her leg, it did not stop her from pursuing her dream. And I am not going to spend the rest of my life feeling sorry for myself. I will live life to the fullest and live like there is no tomorrow.

During the two years that my mom has not been here, I have realized that only one thing has kept my life together, and that is hope. So thank you. Thank you for giving me that. I know that the life I live is not perfection, but it is enough for now. One of the most important things I have learned is that life is a big stinking blob of mess, but that’s the glory of it too.

Gerel Sanzhikov

You can read all the winning letters here, including the winning letters from previous years.

June 26, 2015

Under the Boardwalk

Panorama of beach and boardwalk from pier, Atlantic City. 1897. Prints and Photographs Division.

The travel and tourism industry owes itself to many historical “firsts.” In 1782, Scottish engineer James Watt invented the first steam engine able to turn wheels. On May 10, 1869, the completion of the first transcontinental railroad was commemorated with the driving of a “golden spike.” In 1794, the City Hotel opened in New York City, making it the very first building in America specially built for the purpose of being a hotel. In 1900, the first cruise ship, the Prinzessin Victoria Luise, was built. DELAG, the world’s first airline, was founded on Nov. 16, 1909.

And on this day in history – June 26, 1870 – the very first section of the Atlantic City boardwalk opened along the Jersey Shore. Located on Absecon Island, the boardwalk was also America’s first.

Steel Pier, Atlantic City, N.J. Between 1910 and 1920. Prints and Photographs Division.

Dr. Jonathan Pitney, who thought the island would be a good spot for a health resort, first developed the area in the 1850s. With the help of civil engineer Richard Osborne, the construction of the Camden-Atlantic City Railroad began, and on July 5, 1854, the first tourism train arrived from New Jersey.

Because encroaching sand was a problem, a local railroad conductor and hotel owner petitioned the city council asking that a mile-long footwalk be established. The city used its tax revenues to build an eight-foot-wide temporary wooden walkway from the beach into town that could be dismantled during the winter. In 1880, the boardwalk was replaced by a larger version. More than a decade later, Steel Pier was added, which included a large amusement park.

To get an idea of what sunbathing was like during the early days of the Atlantic City boardwalk, check out this video from 1901 filmed by Thomas Edison.

{mediaObjectId:'E3628D894761047AE0438C93F028047A',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

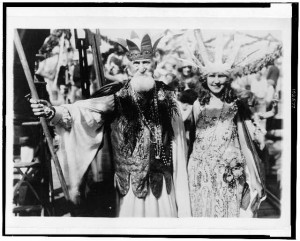

Neptune (Hudson Maxim), Miss America (Margaret Gorman) at Atlantic City Carnival, Sept. 7, 1922. Photo by Bain News Service. Prints and Photographs Division.

These historic images from the Detroit Publishing Company also give a good idea of the boardwalk and beaches around the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

As a way to keep tourists around past Labor Day, the Atlantic City Pageant debuted in 1921 and featured bathing beauties vying for the Golden Mermaid trophy. Miss Margaret Gorman of Washington, D.C. won the first title. From this contest the Miss America pageant was born.

During Prohibition, Atlantic City was a hotbed of activity, with bootleg booze, gambling and other vices appealing to the revelers of the city.

In the 50s and 60s, the boardwalk was popular with stars of stage and screen, including Frank Sinatra, Marilyn Monroe, Dean Martin and Bing Crosby, to name a few.

Atlantic City. Photo by Carol Highsmith, between 1980 and 2006. Prints and Photographs Division.

Today, the Atlantic City boardwalk is known for its casinos, the first of which opened in 1978. And, the Jersey Shore remains a popular destination for locals and East Coast residents.

Travel and tourism are well documented in the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division. The Panoramic Photograph Collection features many images of travel destinations such as amusement parks, beaches, fairs, hotels and resorts.

The Library also has Pinterest boards featuring images of travel and summer fun.

Sources: USA Today, NY Daily News

June 25, 2015

The Hero of Two Worlds

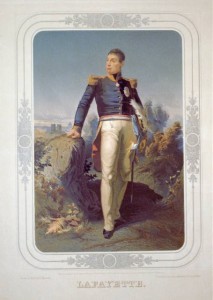

The Marquis de Lafayette. Chromolithograph by P.S. Duval, 1851. Prints and Photographs Division.

The “hero of two worlds” – as the Marquis de Lafayette has been called – has recently been in the news. A replica of the 18th century French frigate that ferried him to America on his most important mission has been making the rounds of the East Coast, on a journey to commemorate the historic relationship between the United States and France. In 1780, the Hermione (pronounced Hair-me-OWN) brought Lafayette to America with news that the French would be supporting the revolutionary cause with money and troops.

This trip was actually Lafayette’s second voyage to America. He first arrived on these shores in 1777, at only 19, to join the Continental Army. He purchased his own ship to make the trip because King Louis XVI forbade him to come.

“He came to America to re-invent himself,” said Laura Auricchio, who was at the Library last Tuesday discussing her new biography on the Marquis. “At Versailles, he was an awkward provincial, unsuited for the life of a courtier. The life he envisioned for himself was a life of military glory.”

The First meeting of Washington and Lafayette, Philadelphia, Aug. 3rd, 1777 . Lithograph by Currier & Ives, c1876. Prints and Photographs Division.

Auricchio did much of her book research at the Library, which holds the microfilm papers of the Marquis de Lafayette. (This article from a 1995 issue of the Library of Congress Information Bulletin offers more insight into the scope and contents of Lafayette’s papers.)

Lafayette was commissioned a major general by Congress, having never fought in battle. According to Auricchio, George Washington thought the title honorary and was uncertain about placing the French nobleman in battle. However, the two men bonded almost immediately – Washington was impressed with Lafayette’s enthusiasm.

Lafayette proved his mettle in the Battle of Brandywine by rallying the troops during the American retreat, all while suffering from a wound in the leg. He was awarded the command of an actual army division following his recuperation.

“Lafayette became the living embodiment of the French-American alliance,” said Auricchio. “Washington was so impressed he took him under his wing.”

Washington and Lafayette at Valley Forge. Painting by John Ward Dunsmore, c1907. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Marquis stayed at Washington’s side in Valley Forge the winter of 1777-78. In these two letters from the Library’s collection of George Washington’s papers dated and , Lafayette discusses military strategy with Washington, as they prepare their departure from camp.

In the June 17 letter, Lafayette writes, “An enterprise against Philadelphia, if successful, would be of an infinite and glorious advantage,” although he goes on the express concern of being discovered by the enemy. Two days later, the Continental Army retook Philadelphia following the departure of the British troops.

Lafayette returned to France in 1779 following campaigns in Barren Hill, Monmouth and Rhode Island. He had hoped to return to America as head of the French forces. While that distinction was ultimately given to Jean-Baptiste de Rochambeau (whose papers are also part of the Library’s collections), Lafayette returned to America in 1780 with Rochambeau and French troops and resumed his position as major general of American forces.

Washington before Yorktown, with the Marquis de Lafayette to the immediate right. Painting by Rembrandt Peale. Prints and Photographs Division.

Lafayette’s forces played a major part in the Virginia campaign and siege of Yorktown in 1781. The Hermione was also part of the blockade that helped lead to the British surrender.

Included in the Library’s map collection are six rare manuscript maps drawn by Michel Capitaine du Chesnoy, the skilled cartographer who served as the Marquis de Lafayette’s aide-de-camp during the American Revolutionary War. As a group, the maps document major aspects of Lafayette’s activities while serving as a volunteer in the Continental Army directly under Washington’s command.

Beautifully drawn, hand colored, and in pristine condition, the Library’s collection includes a detailed map of the Virginia Campaign, dated 1781; two plans of the 1778 military activities in and around Newport, Rhode Island (here and here); a plan of the retreat from Barren Hill in Pennsylvania, 1778; a map of the Battle of Monmouth, New Jersey, 1778; and a map showing troop movements between the battles of Ticonderoga and Saratoga in New York, ca. 1777.

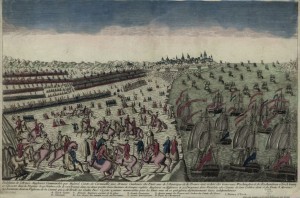

Map showing British, American and French forces at Yorktown. 1781. Geography and Map Division.

The large map of Virginia is considered to be one of the most important examples of Revolutionary War cartography. It documents the many skirmishes and military engagements that took place in 1781 on the long road to victory at Yorktown.

The Library is also home to the Rochambeau Map Collection, which contains cartographic items used by the commander in chief of the French expeditionary army (1780-82) during the American Revolution.

Shortly after the British defeat at Yorktown, the Marquis returned to France. He wouldn’t make another trip to America until 1824, and he never saw Washington again. For the remainder of his life he was an ardent friend and supporter of the United States. You can read more correspondence in Washington’s papers by searching for “Lafayette.” You can also read congressional documents pertaining to the Marquis in the Library’s collection of U.S. congressional documents and debates.

Hermione replica at Mt. Vernon. Photo by Sara Walker, June 2015.

When Lafayette passed away on May 20, 1834, Congress passed a to honor “the friend of the United States, the friend of Washington and the friend of liberty.” Both houses of Congress were “dressed in mourning for the residue of the session,” members wore mourning badges for 30 days (and it was recommended that the American people do the same), and it was requested that John Adams give an oration on the life and character of Lafayette at the next session.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers