Library of Congress's Blog, page 166

December 25, 2013

Start a Holiday Tradition – Trace Your Family Genealogy

The Library of Congress has one of the world’s premier collections of U.S. and foreign genealogical and local historical publications. The Local History and Genealogy Reading Room, located in the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building, is the hub for such research. More than 50,000 genealogies and 100,000 local histories comprise its collections. The Library’s royalty, nobility and heraldry collection makes it one of only a few libraries in America that offer such resources.

(The following is a guest post by Anne Toohey, reference librarian in the Local History and Genealogy section, Humanities and Social Sciences Division.)

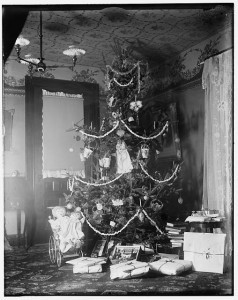

Family Christmas dinner. 1921. Prints and Photographs Division

Oral history has been the main way of preserving family and tribal memories since before the invention of writing and is an important part of family social networking in the present digital age. During the holiday season, family gatherings provide many opportunities to add to your family history. Sharing family stories can take place in a very informal and conversational way.

The holiday dinner table provides a venue for relatives of several generations to share and compare experiences, to discover stories unique to the various generations, and to build not just family memories but social networks with cousins and relatives with whom one interacts less often. Sometimes different branches of the family know different versions of the same story, and comparison adds details and veracity to the story itself.

One of the first things to do when compiling a family history is to interview your older relatives. They can also be a great source of stories that can enrich your family history with personal accounts, as well as give clues for further research to set the family in historical context. Most family stories have at least a grain of truth, even if the details are not exact. And as you conduct genealogical research in primary sources such as vital records and census records to verify the facts in the stories, and to set these memories in historical context, the memories of your relatives will be made more accurate and useful for the compiled family history.

It is often better to ask open-ended questions, and the open style may actually be preferable for family gatherings because it allows opportunities to form new questions about a particular family member or story. For instance, for a family story about how dad dropped the Meissen dinner platter with the turkey on it one Christmas, some may wish to ask what was special about the Meissen dinner plate, how it was acquired, whether they had lived or visited Germany, how mother felt about losing her antique and whether it could be fixed and replaced. Some might want to know what was served after the turkey slid to the floor and whether there was a Fido who complicated the story. These questions may be based on individual interests of family members but may elicit further truths from the storyteller.

The genealogist in the family may want to also intersperse more targeted fact questions to elicit information about specific birth or death dates, places lived or specifics about personalities and experiences of themselves or past ancestors whom they knew or have heard about. These questions can help target further genealogical research.

Oral history can help to shape family memories and add details to family stories that can become the foundation of further research into family history. Formal oral history might depend on setting up interviews, recording audio or visual accounts and transcribing these accounts, and sometimes might be conducted with non-relatives. While the formal style may not enhance the more informal conversations at the family dinner table, the many websites with lists of questions for conducting oral history on the web, and sites devoted to the open and closed interview styles, may help you to shape more informal family conversations.

The Library of Congress can help find books about oral history, find facts about the family or the geographic location, and find places to archive family history. For instance, an existing Bibliography of Books about Oral History can be searched in the Library of Congress catalog, or in World Catalog (often available at public libraries) to provide access (sometimes digital; sometimes analog) to these books. Remote access to reference librarians is available through Ask a Librarian.

You can also archive your family memories at the Library of Congress. You can archive your compiled family history at the Library of Congress. Oral history can be archived also at the Library of Congress through StoryCorps – one of the largest oral history projects of its kind and preserved at the American Folklife Center – and the Veterans History Project, a project to preserve personal accounts of American war veterans.

There are many social networking sites on the web where you can share your family memories and find lost cousins whom you never knew existed. Family history is a great gift and a legacy to the younger family members who may not normally hear the stories. For those who may be solo for the holidays, consider interviewing neighbors and friends!

The Library of Congress blog will bring you more helpful tips, ideas and resources to aid in your genealogy research in the coming weeks.

December 24, 2013

Highlighting the Holidays: Santa Claus is Coming to Town

Santa Claus is one of the most popular and recognizable figures surrounding the Christmas season. He brings us gifts and inspires imagination, so what’s not to love? While he may bring joy to young and old alike, he can also be a bit frightful. We all know the scene in the mall of upset children getting their photos taken with St. Nick.

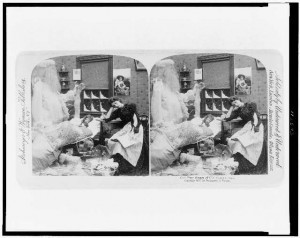

Our pets dream of old Santa Claus/Strohmeyer & Wyman. 1897. Prints and Photographs Division

The Internet is full of websites featuring awkward photographs of the man in the big red suit, and the Library of Congress has some in its collections as well. For example, this photo, dated 1897, features a ghostly Santa standing over a woman and child while they sleep.

The image is a stereograph, which consists of two nearly identical photographs or photomechanical prints, paired to produce the illusion of a single three-dimensional image, usually when viewed through a stereoscope. The Prints and Photographs Division’s holdings include images produced from the 1850s to the 1940s, with the bulk of the collection dating between 1870 and 1920.

Searching for “Santa Claus” in the Library’s stereograph collection pulls a few other interesting finds you don’t want to miss.

More historical holiday fun from the Library of Congress can be found here. Happy Holidays!

December 22, 2013

Highlighting the Holidays: A Special Telegram

On Dec. 22, 1864, William T. Sherman sent President Abraham Lincoln a telegram that included a pretty monumental “gift,” according to the Civil War general.

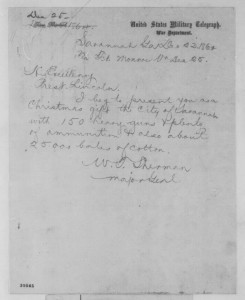

William T. Sherman to Abraham Lincoln, Thursday, Dec. 22, 1864. Manuscript Division.

“I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah with 150 heavy guns & plenty of ammunition & also about 25.000 bales of cotton.

W. T. Sherman

Major Gen”

From Nov. 15 to Dec. 21, 1864, Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman of the Union Army campaigned through Georgia – his famous “March to the Sea” – with troops capturing Savannah on Dec. 21. His forces laid waste to the southern state and its cities, destroying military targets, industry, civilian property and the South’s economy.

Just a few days later, Lincoln sent back correspondence acknowledging the “gift.”

“My dear General Sherman.

Many, many thanks for your Christmas-gift — the capture of Savannah.

When you were about leaving Atlanta for the Atlantic coast, I was anxious, if not fearful; but feeling that you were the better judge, and remembering that “nothing risked, nothing gained” I did not interfere. Now, the undertaking being a success, the honor is all yours; for I believe none of us went farther than to acquiesce. And, taking the work of Gen. Thomas into the count, as it should be taken, it is indeed a great success.2 Not only does it afford the obvious and immediate military advantages; but, in showing to the world that your army could be divided, putting the stronger part to an important new service, and yet leaving enough to vanquish the old opposing force of the whole — Hood’s army — it brings those who sat in darkness to see a great light. But what next? I suppose it will be safer if I leave Gen. Grant and yourself to decide.

Please make my grateful acknowledgments to your whole army, officers and men.

Yours very truly

A. Lincoln.”

The Library of Congress continues its holiday highlights with more historical finds. You can read other holiday-related blog posts here.

December 20, 2013

Highlighting the Holidays: A Kodak Moment

They say a picture is worth 1,000 words, and in the early 20th century, the Kodak Company wanted to make sure you were fully equipped to capture those moments, particularly for the holidays.

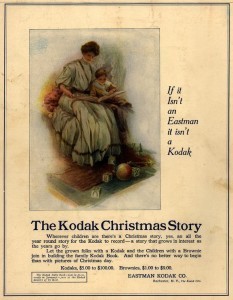

The Kodak Christmas Story. 1907. Duke University

In this ad from the Eastman Kodak Co., (1907), consumers were encouraged to buy a Kodak camera to capture their own Christmas story.

“Wherever children are there’s a Christmas story, yes, and all the year round story for the Kodak to record – a story that grows in interest as the years go by.”

“Let the grown folks with a Kodak and the Children with a Brownie join in building the family Kodak Book. And there’s no better way to being than with pictures of Christmas Day.”

The Brownie was a long-running popular series of simple and inexpensive cameras made by Kodak that really introduced the concept of the “snapshot.” Kodak advertisements particularly targeted children when promoting this camera because of its simplicity and ease of use.

These advertisements are part of “The Emergence of Advertising in America,” presented in partnership with Duke University. More than 9,000 images illustrate the rise of consumer culture, especially after the American Civil War, and the birth of a professionalized advertising industry in the United States.

More historical holiday finds from the Library of Congress can be found here. Happy Holidays!

December 19, 2013

Highlighting the Holidays: Tree Time at the Wright Brothers’ House

Twinkling lights, multicolored ornaments, sparkly tinsel, hanging candy canes – trimming the Christmas tree is a tradition of the holiday season, for those that celebrate.

Christmas tree in the Wright home, 7 Hawthorn Street, Dayton, Ohio. 1900. Prints and Photographs Division.

At 7 Hawthorn Street in Dayton, Ohio, the Wright Brothers decorated their tree with popcorn garland, candles, paper angles angels, sparkly ornaments and a star topper.

In this picture, ca. 1900, from the Library’s collection of Wilbur and Orville Wright Papers, you can see a variety of gifts, mainly for children, stuffed under the tree: a couple of dolls perched atop a stroller, boxes of miniatures for a dollhouse, a toy train, several wrapped packages, possibly a pair of skates and a BB gun, perhaps.

Wilbur and Orville Wright never married but rather lived together in the Hawthorn Street house with their father and sister Katharine. The home was where much of brothers’ creative thinking and planning took place, including the invention of the world’s first airplane. Orville and Wilbur resided at the Hawthorn Street house until Wilbur’s death in 1912.

More historical holiday treasures from the Library of Congress can be found here. Happy Holidays!

December 18, 2013

Highlighting the Holidays: A Magical Card

Happy holidays from the Library of Congress! With more than 155 million items in its collections, it’s no surprise that the institution could really celebrate the season all year, highlighting a variety of holiday-related items. We’ll deck the halls for the next several days featuring historical holdings from the nation’s library.

Christmas card from Mrs. Harry Houdini. 1935. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

While this card,ca. 1935, may not have magically appeared in mailboxes, its recipients were receiving a bit of cheer from, as the card states, “the oldest living lady magician in the world.”

Beatrice “Bess” Rahner was a performer in her own right when she married Ehrich Weiss. Together they became the well-known couple Mr. and Mrs. Harry Houdini. In the early years of their marriage, they performed in full partnership on stage. Harry ultimately became the star of the show, and they both devoted themselves to his career. However, Beatrice knew and could practice the art of illusion and, as this card documents, she recognized her role as such.

Following Harry’s death Oct. 31, 1926, Bess moved to Hollywood to continue promoting her husband’s memory and legacy. In fact, she kept a full-time publicist on her payroll for 16 years after his death, just to keep his legend alive.

Calling Mr. Wolfe

Quick: what do the movies “Mary Poppins” and “Pulp Fiction” have in common?

Well, yes, they’re both motion pictures. But now, both are listed on the Library of Congress National Film Registry, a collection of films – 25 are added each year – deemed worthy of preservation due to their cultural, historic or aesthetic significance.

Julie Andrews as the fix-it lady who dropped out of the sky

Furthermore, both feature characters who swoop in and help others sort out their messes, literally or figuratively – Mary Poppins (played by Julie Andrews) in that movie, and Winston Wolfe (played by Harvey Keitel) in “Pulp Fiction.”

After that, it’s all contrast – one’s family fare, the other’s, ah, not. One features a song called “I Love to Laugh,” while the other makes you hate yourself for finding something so dark so funny.

This year’s list (which brings the grand total in the registry to 650) also includes John Ford’s Irish love story “The Quiet Man,” the U.S. space-program history “The Right Stuff” and the 1960s Edward Albee play-turned-movie “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf,” starring the Brangelina of the 1960s, the married actors Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. Instead of “Mr. and Mrs. Smith” the Liz & Dick movie could have been called “Mr. and Mrs. Snider” – the more they drink in this flick, the snider they get.

This year’s additions also include “The Magnificent Seven,” which of course is the 1960 cowboy remake of Akira Kurosawa’s classic of feudal Japan, “The Seven Samurai” and “Forbidden Planet,” a 1956 science-fiction classic that featured Leslie Neilsen as a serious character.

Surely.

There are also several films of artistic or historic value, including the 1919 silent film “A Virtuous Vamp” and the 1966 documentary “Cicero March,” about a revealing event in the Civil Rights Movement. And tucked into this year’s list is the 1989 provoc-umentary “Roger & Me” by Michael Moore.

You can, and should, nominate films to be considered for the National Film Registry. The online form to submit your suggestions can be found here, and you might also want to refer to a list of movies that haven’t yet made the cut. Please participate!

December 16, 2013

You’re Supposed to Steep Tea in Boiling Water

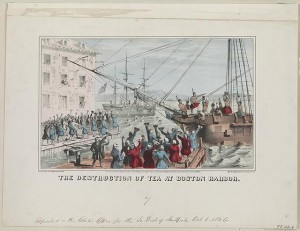

The destruction of tea at Boston Harbor. 1846. Prints and Photographs Division.

On Dec. 16, 1773, a group of Bostonians dressed as Mohawk Indians boarded ships docked in Boston Harbor and dumped some 340 chests of tea into the water. Today marks the 240th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party.

“A number of brave & resolute men, determined to do all in their power to save their country from the ruin which their enemies had plotted, in less than four hours, emptied every chest of tea on board the three ships commanded by the captains Hall, Bruce, and Coffin, amounting to 342 chests, into the sea!! without the least damage done to the ships or any other property. The matters and owners are well pleas’d that their ships are thus clear’d; and the people are almost universally congratulating each other on this happy event,” reads an article from the Dec. 20, 1773, edition of the Boston Gazette, recounting the details of the infamous nonviolent political protest.

This protest was a challenge against the Tea Act of 1773, which gave the nearly bankrupt British East India Company a monopoly on tea exports to America and forced the colonists to acknowledge British taxation, a thorn in their sides due to a monumental war debt from the French and Indian War. The Tea Act, and the facts that the colonists were required to provide room and board to the British standing army in America and had to pay taxes on everything from molasses to paper goods to glass, were all fuel to the fire of the impending American Revolution. Although Parliament repealed most of these taxes, the seeds of resentment, mistrust and anti-establishment had been planted in the colonists’ minds.

Most colonists applauded the action of the Boston Tea Party, while the powers-that-be in London reacted swiftly and severely. In March 1774 Parliament passed the Intolerable Acts, which closed the port of Boston and stripped Massachusetts of self-government, among other measures. The American Revolution began a year later.

The guide “The American Revolution, 1763-1783” documents this tumultuous time in American history from British reform and colonial resistance to America’s war victory through various Library of Congress collections and presentations. This resource is one of several that highlights the ups and downs of the nation’s development, from its early beginnings as a settlement to a post-war United States.

December 13, 2013

Uncovering a Treasure

(The following is an article written by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library of Congress staff newsletter, The Gazette.)

The file boxes of Charles and Ray Eames yielded all sorts of eclectic items to archivists processing the collection at the Library of Congress – a letter from Georgia O’Keefe in this one, a receipt for a Moroccan robe in that one, printed butterflies in another.

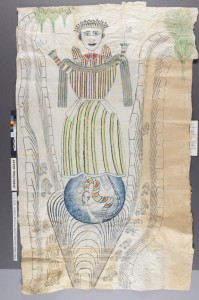

An untitled Madonna by Martín Ramírez, ca. 1951. Estate of Martín Ramírez / Prints and Photographs Division

Buried in one carton, senior archives technician Tracey Barton found a crumpled, yellowed tube of paper that, when unrolled, revealed an astonishing image: a crowned Madonna standing atop a blue orb, a snake at her feet devouring a rabbit, cars riding down canyon roads, all drawn in childlike fashion in pencil, crayon and colored inks. The flip side was equally amazing.

The paper support was constructed of more than 20 pieces of junk mail – postmarked envelopes, solicitations for racy photos, ads for gardening supplies – glued together. The artwork bore no obvious connection to the Eameses, a husband-and-wife team that in the 1940s and ’50s pioneered modern design in furniture and architecture.

Sorting through the miscellany of their lives, Barton had made a stunning discovery: a previously unknown work by an artist described in the New York Times as one of the most important of the last century.

Barton, a senior archives technician in the Manuscript Division, in 2009 had begun processing a large and disorganized addition – about 220 boxes – to the Library’s collection of Eames material.

“It was very, very eclectic, which is what I love about the chaos of this addition,” she said. “You never know what you’re going to find.”

The artwork Barton found bore no signature, but the makeshift canvas offered clues to the creator’s identity: The junk mail was a strong sign the piece was an example of “outsider art,” a term generally applied to the work of self-taught artists.

Barton conducted an online search based on her hunch about the nature of the piece and on places and dates she lifted from the junk mail: “Auburn California 1951 outsider art.”

“All of a sudden, Martín Ramírez came up,” she said.

Ramírez, it turned out, was a prominent figure in outsider art, and the style of the drawing Barton discovered perfectly matched other examples of his work.

The artwork’s paper support is made up of more than 20 pieces of junk mail – ads for gardening supplies, racy photos, vitamins and magazine subscriptions. Photo by Abby Brack Lewis

In recent years, Ramírez has been the subject of two major retrospectives at the American Folk Art Museum in New York and one at the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid. The New York Times, in a review of the 2007 show at the folk art museum, called Ramírez “simply one of the greatest artists of the 20th century.”

“From the moment his work was seen by his first champion, nobody has ever doubted the beauty, the importance and the cultural significance of Ramírez’s art,” said Brooke Davis Anderson, who curated the shows in New York and Madrid. “He’s never had a bad review.”

An Immigrant’s Tale

Ramírez’s story is fascinating and tragic. He grew up in Mexico, got married, had children and, in 1923, bought a small ranch in the state of Jalisco. Two years later, he emigrated alone to California, where he hoped to find work that would support his family. Because of political and religious strife in Mexico, Ramírez decided not to return home.

He would never see his family again.

Ramírez, impoverished and disoriented, was arrested in 1931 and hospitalized at Stockton State Hospital, where he eventually was diagnosed as schizophrenic.

In the mid-1930s, he began to make drawings using whatever paper was at hand – scraps from examination tables, bags, magazines, envelopes, bits glued together with a paste of bread or potatoes mixed with saliva. On these canvases, he created images that reflected the traditions of his Mexico home and his experiences in California – Madonnas and caballeros, churches and tunnels, trains and animals.

Martín Ramírez / Estate of Martín Ramírez

In 1948, Ramírez was transferred to DeWitt State Hospital near Sacramento, where he lived the rest of his life – and where his art was discovered.

Tarmo Pasto, a professor of psychology and art at Sacramento State College who frequently visited DeWitt, began to supply Ramírez with material and to save his art. He also arranged for shows of Ramírez’s art in the early 1950s.

Solving a Mystery

Barton frequently shared her discoveries with Margaret McAleer of Manuscript, who serves as the Eames collection’s main archivist. Barton and McAleer were moved by Ramírez’s story and by the piece Barton found.

“I thought it was gorgeous,” McAleer said. “It amazes me that someone who tragically was in a psychiatric facility – and whatever he was dealing with in his mind – could have created such a composition.”

Still, a big question remained: How did this artwork make the unlikely journey from a psychiatric ward to a file box at the Library? Barton and McAleer hoped the answer would reveal itself as the collection was processed.

A year after the discovery, McAleer received a three-word e-mail from Barton: “I found it.”

The “it” was the solution to the mystery: a letter to Charles Eames from Don R. Birrell, director of the E.B. Crocker Art Gallery in Sacramento. In the letter, Birrell references a conversation they’d had about “schizophrenic drawings” and informs Charles that he’d just mailed to him several examples of this art to keep “if you wish.”

It all made sense: The Crocker gallery put on Ramírez’s first solo show, and the letter was dated April 9, 1952 – shortly after that show closed.

“I glanced at this letter from a gallery director, and all of a sudden it all came into focus,” Barton said. “I got a chill up my spine.”

The piece found by Barton is one of the earliest Ramírez drawings in existence, according to Victor M. Espinosa, who has extensively studied and written about Ramírez.

A Rare Find

Espinosa says most of the drawings Ramírez made on recycled paper – like the Library’s – were destroyed long ago and that the bulk of his surviving works were produced after 1953, when he had access to drawing paper.

“This is an amazing example of the way Ramírez worked before he had access to regular paper,” Espinosa said.

The image shows Ramírez’s representation of the Virgin Mary as the Immaculate Conception – one of only 15 Madonnas in Espinosa’s database of the roughly 500 known works by Ramírez. At the Madonna’s feet, a snake devours a rabbit – something Ramírez might have seen in Jalisco. The virgin, wearing traditional Mexican garb, holds before her a shawl evocative of another traditional Mexican garment, a rebozo.

“What’s nice about the Madonna is that you see an honoring of a Catholic, iconic tradition, but he’s made it a hybrid figure by giving it a Mexican costume,” Anderson said.

Lynn Brostoff performs an X-ray fluorescence examination of the Martín Ramírez piece. Photo by Katherine Blood

Repairing a Masterpiece

The passing decades – and the time spent rolled up in a file box – took their toll on the piece: The Madonna suffered insect damage, large tears, deep creases and some losses.

After the discovery, Library conservators repaired some damage and stabilized the piece but took a light approach to cosmetic work. What may appear as damage, after all, is part of the piece’s story to tell.

“It is thrilling to welcome this new treasure to the Library’s visual art collections and share Tracey’s discovery with the world,” said Katherine Blood, a curator in the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division. “We are honored that the Ramírez family has entrusted this uniquely compelling piece of the artist’s legacy to the Library’s care.”

The Martín Ramírez Madonna will be on view to the public for three months, through March 15. The piece will be on display in the “Exploring the Early Americas” exhibition on the second floor of the Jefferson Building.

You can learn more about Ramirez and the significance of his painting in this brief video featuring curator Katherine Blood and blog post from the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division.

December 12, 2013

Pic of the Week: Trimming the Tree

It’s beginning to look a lot like Christmas … in the Great Hall of the Library of Congress, that is. Every year, the Library decks its hall with a tall tree, replete with lights and ornaments for the enjoyment of the institution’s patrons. Here, you can see workers are putting on the finishing touches. How do you decorate for the holidays?

Photo by David Rice

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers