Library of Congress's Blog, page 170

September 12, 2013

New Twitter Feed, @TeachingLC, Launches

(Today, one of the Library of Congress blogs, Teaching with the Library of Congress, made an important announcement about its new tool in education outreach.)

The Library of Congress Launches @TeachingLC, Its New Twitter Feed for K-12 Educators

September 12, 2013 by Stephen Wesson

Sharing ideas is a critical part of all great teaching, and now the Library of Congress has a new tool for exchanging ideas with the nation’s K-12 teachers: @TeachingLC, its new Twitter feed for educators.

The Library’s Director of Educational Outreach, Lee Ann Potter, hailed the launch. “Teachers and librarians use Twitter to discover new ideas and inspiration, and we at the Library are happy to be joining the conversation. @TeachingLC will be a great venue for educators to learn from each other and to explore the primary sources and teaching resources offered by the Library of Congress.”

The new Twitter feed will highlight intriguing primary sources, showcase new tools for teachers, and spark discussion between the nation’s K-12 educators and Library experts.

“There is always something new to discover at the Library of Congress, and we’re looking forward to working with teachers to find new ways to fuel student learning and encourage their discoveries.”

The Library of Congress makes available millions of digitized artifacts from across world history and culture, all for free. Primary sources like these have tremendous power to capture students’ attention and to build their critical thinking and analysis skills.

To help teachers bring these primary sources to life in their classrooms, the Library offers free teaching tools and professional learning opportunities on its Web site for teachers, loc.gov/teachers.

We hope you’ll follow us and spread the word! Meanwhile, let us know what you’d like to hear about in @TeachingLC.

September 10, 2013

Carrying a Torch — Ours!

The Library of Congress (top right) overlooks its National Book Festival, which returns to the National Mall Saturday, Sept. 21 and Sunday, Sept. 22

With the Library of Congress National Book Festival just days away (it’s a week from this weekend, Saturday, Sept. 21 and Sunday, Sept. 22, free of charge on the National Mall) we have a lot to share in addition to more than 100 best-selling authors for readers of all ages. One of the great stops at this year’s festival will be the Library of Congress Pavilion.

This year the pavilion will be more packed than ever before with a huge variety of offerings from the Library – it’s your opportunity to sample our “universe under the dome with the torch of knowledge on top,” appetizer-style. The Library of Congress, despite its name, is also your Library, and anyone over the age of 16 can get a reader card and use our reading rooms to do research within our vast collections; we also have a Young Readers Center for children and teens to visit, and several museum-style exhibitions, such as our ongoing blockbuster, “The Civil War in America.” All of this comes to you free of charge from the largest library in the world.

This year at the National Book Festival’s Library of Congress Pavilion, we will have tables featuring curators and other staff from a wide variety of Library divisions; we will also have two theaters where curators and other Library leaders will give brief presentations about their areas of expertise. Both Saturday and Sunday, these leaders will give fascinating talks about topics ranging from Copyright and the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped (both of them part of the Library of Congress) to genealogy, preservation, educational outreach, the aforementioned Young Readers Center, the Law Library of Congress, the Prints & Photographs Division, the Recorded Sound Collections, numerous collections based on regions of the world, the World Digital Library, and the Music Division. Signs with times will be posted, and times will be in the official program as well, or you can view the schedule here.

There will be talks by curators from our Civil War exhibition and the Geography & Map Division; the Veterans History Project; and the project that preserves old newspapers from all over the country for digital perusal.

The Library of Congress Pavilion also will hold a display on “Books That Shaped the World,” which will offer you the chance to vote via survey to nominate a book you believe shaped the world or jot its title on our giant whiteboard. Come be heard!

And one more thing – for those of you who’ve wanted to go home with a National Book Festival T-shirt – we will be offering T-shirts in designs for adults and kids at a special sales tent across the street north of the grounds, in front of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. It’s near the book-signing area – come check it out.

The Library of Congress National Book Festival will take place, rain or shine, on Saturday, Sept. 21 from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. and on Sunday, Sept. 22 from noon to 5:30 p.m. on the National Mall, between 9th and 14th Streets. Don’t miss it!

September 6, 2013

InRetrospect: August Blogging Edition

Let’s take a look back at some of the posts populating the Library of Congress blogosphere in August.

In the Muse: Performing Arts Blog

“We’ll walk hand and hand someday” — Music and the March on Washington

Music played a pivotal role in the March on Washington.

Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business

No Opera, No X-Rays!

Researcher Mark Schubin talks about the deadliness of opera and x-rays.

In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress

Odd Laws of the United Kingdom

From plague-free taxi rides to no gambling in a library, Clare Feikert-Ahalt discusses U.K. law.

The Signal: Digital Preservation

Rich Online Resources Document the 1963 March on Washington

Bill LeFurgy presents other resources related to the historical civil rights event.

Teaching with the Library of Congress

Looking Behind the March on Washington: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the Civil Rights Movement, and Labor in Primary Sources

Primary sources from the Library of Congress can help students learn more about the march.

Picture This: Library of Congress Prints & Photos

Summer Road Trip: From Sea to Shining Sea

Kristi Finefield writes on bygone era road trips.

From the Catbird Seat: Poetry & Literature at the Library of Congress

The Secret Anniversaries of the Heart

Director of Ed Outreach Lee Ann Potter talks about poetry in her life.

Library in the News: August 2013 Edition

August saw the opening of two new exhibitions at the Library of Congress. On Aug. 14, the Library exhibition “A Night at the Opera” debuted followed by “A Day Like No Other: 50 Years After the March on Washington” on Aug. 28. Both exhibitions received a variety of headlines.

“They came to Washington, D.C. with determination in their hearts and freedom on their minds. … They were from all walks of life, all races and all denominations. They were old and young, able-bodied and impaired, poor and wealthy, average citizens and the very famous, all sharing the same mission and goal – to be a part of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom,” wrote Yahoo! News. “This exhibition transports visitors to that momentous day, August 28, 1963 – a day that transformed our nation – when 250,000 people participated in the largest non-violent demonstration for civil rights that Americans had ever witnessed.”

In a headline that read “How to Commemorate the March On Washington Without Ever Leaving Your Computer, “ Popular Science highlighted the Library’s collection of march photos from U.S. News & World Report, in addition to linking to Library blog posts about the historical event.

Other outlets running features on the March on Washington exhibition included the Examiner and broadcast outlets WTTG Fox DC, NBC DC and WTOP (here and here).

Reviewing “A Night at the Opera” was the Washington Post’s Anne Midgette.

““A Night at the Opera,” an exhibition that opened last week at the Library of Congress and will travel to Disney Hall in Los Angeles in 2014, represents a lot of goals packed into a single show of about 50 objects. This makes it a fitting tribute to an art form that involves several different art forms — visual arts and theater, dance and music — packed into a single performance,” wrote Midgette.

“Opera buffs are as likely to feel as tantalized as fulfilled by glimpsing only individual items from the many archives and collections within the library’s holdings.”

Continuing to make the news are the Library’s preservation efforts, including its work in archiving tweets since Twitter’s inception in 2006. Robert A. Lehrman of The Christian Science Monitor spoke with the Library’s Jane Mandelbaum and Thomas Youkel, who are leading the project team.

“Mandelbaum and Youkel pool their knowledge to figure out how to archive the tweets, how researchers can find what they want, and how to train librarians to guide them,” Lehrman wrote.

“Historians want to know not just what happened in the past but how people lived. It is why they rejoice in finding a semiliterate diary kept by a Confederate solider, or pottery fragments in a colonial town,” he continued.

September 5, 2013

Saving Pulp Fiction

Photo by Shealah Craighead.

(The following is a story written by Lindsey Hobbs of the Library’s Preservation Directorate for the Library of Congress staff newsletter, The Gazette.)

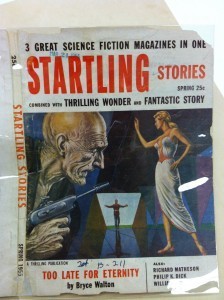

Pulp-fiction authors created some of the most enduring characters of any literary genre including Tarzan, detective Sam Spade, and the sword-wielding Zorro.

The magazines that illustrated their exploits, unfortunately, haven’t fared as well. In fact, they never were built to last – the pulps were printed on cheap, wood-pulp paper (hence the name “pulp fiction),” which quickly became brittle and acidic.

Technicians in the Preservation Directorate, however, are working to give new life to the lustrous, eye-catching covers in the Library of Congress’s sprawling collection of pulp-fiction magazines. The Serial and Government Publications Division holds roughly 14,000 issues from more than 300 titles published in the United States between the 1920s and 1950s.

“American popular culture is an ever-expanding scholarly field, and the pulp magazines were a publication type that was popularized in America,” said Georgia Higley, head of the Newspaper Section in the Serials Division. “Anyone studying magazine history considers the covers important primary sources.”

The Library transferred most of the pulp serials to microfilm years ago because of the rapidly deteriorating wood-pulp paper. It was immediately apparent, however, that the color limitations of microfilm diminished the vibrant graphics.

“Since even the best microfilming efforts do not adequately reproduce illustrative material, especially color images, the pulp magazine cover collection preserves an aspect of the original that would otherwise be lost to researchers here at LC,” Higley said.

As a result, the Collections Conservation Section is conserving the original covers, and the Preservation Reformatting Division oversaw the creation of preservation facsimiles of much of the remaining text.

Nathan Smith of the Collections Conservation Section demonstrates paper repair on the cover of a pulp-fiction magazine. Photo by Shealah Craighead.

Pulp-fiction serials rose to popularity primarily in the first half of the 20th century, as new technology permitted cheap, mass production and a more literate working class sought new sources of entertainment.

Not known as purveyors of good taste, the pulps covered everything from romance and adventure to westerns and detective stories to horror and science fiction.

The racier versions, known as “spicy” pulps, most often featured a scantily clad damsel in distress on the cover. Although the spicy pulps enjoyed wide popularity in their day, none occupy the Library’s shelves – they were deemed unsuitable for collection at the time.

The striking cover art, which was at its most whimsical on the sci-fi and fantasy pulps, was a key factor in marketing and even story development.

Often, artists created a cover that would lure readers at newsstands, and writers then would develop stories around the illustrated theme.

Some artists made careers working exclusively for pulp magazines – Margaret Brundage created dozens of covers for “Weird Tales,” widely considered the greatest of the horror and fantasy pulps.

This issue of Startling Stories featured works by Philip K. Dick, whose later novels served as the basis for films such as “Blade Runner” and “Total Recall,” and Richard Matheson, whose novel “I am Legend” has been adapted for the screen three times. Serials and Government Publications Division.

In addition to the glossy covers, pulp magazines also are notable for the many now-famous authors who got their start writing stories for as little as a third of a penny per word – Ray Bradbury, Dashiell Hammett, H.P. Lovecraft, Isaac Asimov, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Raymond Chandler. Even a young L. Ron Hubbard became a star pulp writer before publishing his pre-Scientology treatise “Dianetics” in the pulp magazine “Astounding.”

Conspicuously absent from the list are any widely recognized female authors. Women pulp writers often used pseudonyms or disguised their first names by only using their initials.

Mary Elizabeth Counselman, for example, wrote stories for “Weird Tales,” and Dorothy McIlwraith served as editor of both “Weird Tales” and “Short Stories” for more than three decades. Leigh Brackett wrote science fiction as well as hard-boiled detective stories and went on to write novels and screenplays, including the script for George Lucas’ “The Empire Strikes Back.”

Since a large number of the serials still are in copyright, digitization is not yet an option.

For now, Collections Conservation technicians are performing many tedious hours of paper repair and rusty staple removal, as well as creating a custom protective enclosure for each cover. Once the project is completed, CCS will have conserved more than 600 individual covers, which will return to the vault of the Serials Division in a condition suitable for handling by researchers.

The pulp-fiction era came to an end in the 1950s with the rise of the paperback novel and television, but the magazines continue to serve as a unique resource of pop-culture history.

The conservation work will allow researchers a more authentic and, likely, a more enjoyable experience.

Said Higley: “We’ll be able to offer researchers the chance to re-create the experience people had reading them.”

September 4, 2013

Inside the March on Washington: Moving On

(The following is a guest post by Guha Shankar, folklife specialist in the American Folklife Center and the Library’s project director of the Civil Rights History Project, and Kate Stewart, processing archivist in the American Folklife Center, who is principally responsible for organizing and making available collections with Civil Rights content in the division to researchers and the public.)

For sisters Dorie and Joyce Ann Ladner, the highs of witnessing the flood of people on the National Mall, the celebrities, the media presence and the speeches on the Lincoln Memorial steps were short-lived. The aftermath of the March on Washington for the Ladners and fellow activists in the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee and other groups meant a return to confront racism in the increasingly tense and violent front-line communities in Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and other southern states. If the activists were “under siege” before the march, the tension in the places where they organized only intensified afterwards.

In listening to insiders’ perspectives on the March on Washington in 1963 and considering subsequent historical developments, the gathering appears to have provided an important, but only momentary, pause in the deepening conflicts in much of the nation. Across all sectors of society, anxiety was rising over the pace and the form of social change that was unfolding. The days, months and years after August 1963 in America saw a parade of events – horrific as well hopeful – that raised fundamental questions about the character of American society, the legitimacy of the political structure and the precarious prospects for orderly change.

A brief snapshot of such symptomatic moments over the course of just five years would have to include John F. Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963; the murder of “Freedom Summer” student volunteers James Earl Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner in June 1964; passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964; the “Bloody Sunday” march in 1965; the murder of civil rights worker Jonathan Daniels in 1965; the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965; and the murders of Martin Luther King in Memphis in April 1968 and Robert Kennedy in June of that same year.

In the first excerpt in this video, drawn from the Civil Rights History Project, the Ladners remember the energy dedicated to planning and pulling off the march was almost immediately overwhelmed by the horror of the murder of four school girls in the bombing of Sixth Street Baptist Church Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala. This happened on Sept. 15, 1963, only a little over two weeks after the march’s culmination, and the Ladners recall the moment of contradiction between being at the march one minute and attending the funeral of the school girls the next.

In the final video excerpt in this series on the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, we draw on an interview with the Rev. Benjamin Lowery from the National Visionary Leadership Project Collection. Lowery, a close friend of Martin Luther King and a key figure in the Civil Rights Movement, reflects on King’s pragmatic goals and worldly ideas for achieving fundamental transformations in American society. Lowery notes that King’s vision of achieving economic self-sufficiency and political equality for all Americans was aligned with an anti-militaristic stance and that these aspirations have become obscured by the focus on the “dream” that has come to define the man.

{

shortName: '',

detailUrl: '',

derivatives: [ {derivativeUrl: 'rtmp://stream.media.loc.gov/vod/blogs/afterm...'} ],

mediaType: 'V',

autoPlay: false,

playerSize: 'mediumWide'

}

This blog series accompanies the Library’s photo exhibition, “The March on Washington: A Day Like No Other,” which is on view at the Library though Saturday, March 1, 2014.

September 3, 2013

The Reward of Courage

Picture this: The battle of good versus evil set against the backdrop of early 19th century America, where the coming together of two young lovers is threatened by the mistaken belief of an inheritable disease that would afflict their future children. Charlatans who promise quack cures in place of scientific medicine are pitted against the U.S. postal authorities, who crack down on such fraudulent and dangerous claims.

Miss Keene, the nurse at Dr. Dale’s clinic, examines Anna Flint. This is probably the first cinematic representation of a breast examination for cancer.

Sounds like a period science fiction thriller, right? In 1921, the American Society for the Control of Cancer (the ASCC, later renamed the American Cancer Society) produced and the Rockefeller Foundation funded the melodrama “The Reward of Courage.”

The film calls for the establishment of clinics in industrial workplaces to promote worker health and higher productivity, and provides what is likely the first representation in film of a breast examination for cancer.

The Library of Congress acquired the original nitrate print of “The Reward of Courage” in 1998 from the National Film and Sound Archive in Australia (NFSA) as part of an ongoing partnership to repatriate American titles in the NFSA collections.

Today, the National Library of Medicine (NLM) announced the digital release of both the original version of “The Reward of Courage” and the newly scored version, on the NLM’s Medical Movies on the Web, a curated portal featuring selected motion pictures from the NLM’s world-renowned collection of over 30,000 audiovisual titles.

You can watch both the original silent version and the newly scored version of the film on NLM’s YouTube channel.

Part of the animated section of the film shows the spread of cancer and its consequences, highlighted by arrows. The line drawing of the human figure and dark blotches of the tumors also serve to counter the prospect of any paralyzing fear or disgust that might be evoked by a live action image of tumors.

Working with the Library of Congress Moving Image reference staff, NLM discovered the unpreserved and unstable nitrate print in the Library’s collections while doing research on medical films and, in 2006, received a grant to preserve the film. Library of Congress staff at its Motion Picture Conservation Center in Dayton, Ohio pulled the 1,750-foot 35mm reel to make a thorough examination of each frame for repair and cleaning. The film was then sent to Colorlab in Rockville, Md., for the rest of the preservation work, as the original nitrate print was tinted and the Library does not preserve color film, explained Mike Mashon, head of the Library’s Moving Image Section. In exchange for loaning its material, the Library received both a new 35mm safety preservation negative and a tinted safety access print.

“`It’s a fascinating early example in the use of motion pictures to educate moviegoers about public health issues, in this case using a framing narrative of a young couple who fear that their children will inherit a familial predisposition to cancer,” said Mashon. “The Library has thousands of these types of educational films in its collections, films that provide invaluable and vivid examples of the ways in which films have from the very beginning of cinema been used to teach, persuade, cajole, sell and indoctrinate the American public.”

Because of neglect and deterioration over time, more than 80 percent of U.S. movies from the silent era no longer exist in the United States. The Library maintains the largest collection of American films on nitrate film stock in the world, and continues to work with foreign archives to return domestically made films to the United States.

August 30, 2013

Imagination and Invention

“To invent, you need a good imagination and a pile of junk.” – Thomas Edison

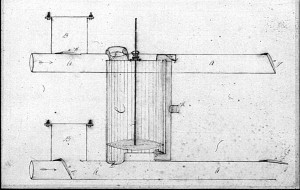

John Fitch’s sketch and description of piston for steamboat propulsion, ca. 1795. Manuscript Division.

In August 1795, John Fitch not only demonstrated the first successful steamboat but was also granted a United States patent for his invention. A century later, on Aug. 12, 1877, Thomas Alva Edison is believed to have completed the model for the first phonograph, a device that recorded sound onto tinfoil cylinders. Twenty years later, on Aug. 31, the inventor, often referred to as the “Wizard of Menlo Park,” received a patent for the kinetoscope, the forerunner of the motion picture film projector. With the month proving to be a notable one in our nation’s invention history, it is quite appropriate that August is National Inventor’s Month.

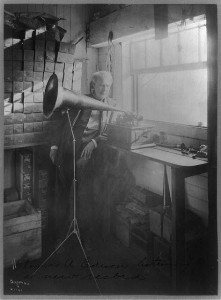

Thomas Edison listening to a new record. 1906. Prints and Photographs Division.

Created in 1995 by the United Inventors Association of the USA (UIA-USA), the Academy of Applied Science and Inventors’ Digest, this annual commemoration aims to guide up-and-coming inventors, young and old, on the processes of product development, inspire creativity and innovation, and promote the positive image of inventors and their contributions. The Library of Congress could be considered an avid supporter, with its American Memory Edison collection titled “Inventing Entertainment: The Motion Pictures and Sound Recordings of the Edison Companies.” The presentation contains surviving products of Edison’s entertainment inventions and industries, including motion pictures, disc sound recordings, and other related materials, such as photographs and original magazine articles. In addition, histories are given of Edison’s involvement with motion pictures and sound recordings, as well as a special feature focusing on the life of the great inventor.

An interesting side note, according to “Washington D.C. Museums: 2013 Video and Social Media Rankings” – a report on 42 District-area cultural institutions put together by arts and culture blog ItsNewsToYou.me – the top-viewed D.C. museum video (329,000 views) is “Edison’s Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze.” “The Sneeze” was one of the inventor’s first motion pictures and captures Edison employee Fred Ott, who was known to his fellow workers for his comic sneezing and other gags. The Library received it as a copyright deposit on Jan. 9, 1894. “Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze” is also the earliest extant copyrighted motion picture in the Library of Congress collections.

August 28, 2013

Inside the March on Washington: Speaking Truth to Power

(The following is a guest post by Guha Shankar, folklife specialist in the American Folklife Center and the Library’s Project Director of the Civil Rights History Project, a Congressionally mandated documentation initiative that is being carried out in collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.)

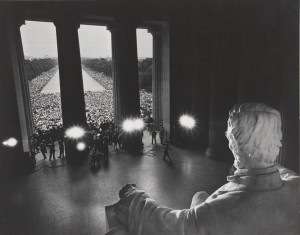

Photographer James K. W. Atherton, UPI, White House News Photographers Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Dr. Martin Luther King’s speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963 gained mythic status at virtually the moment it was delivered, and its aura has only increased over the years. By virtue of its having been added to the Library’s National Recording Registry in 2002, it is also officially a national treasure, taking its place alongside the recordings of Robert Johnson, Cole Porter, Marian Anderson, the Fisk Jubilee Singers and dozens of other unique American voices.

In this interview from the Civil Rights History Project Collection, Clarence Jones speaks with David Cline of UNC-Chapel Hill’s Southern Oral History Program about drafting the famous speech. Jones, King’s speech writer and adviser, recalls in vivid detail the moment at which King departed from the draft to include, without any prior warning, the “I Have a Dream” portion of the speech. We also hear an excerpt from Rev. Joseph Lowery in an interview for the National Visionary Leadership Project Collection. Lowery, a confidante and colleague of King, reminisces about the enduring power of the speech in the wider context of the place and time in which it was delivered.

{

shortName: '',

detailUrl: '',

derivatives: [ {derivativeUrl: 'rtmp://stream.media.loc.gov/vod/blogs/Dream_...'} ],

mediaType: 'V',

autoPlay: false,

playerSize: 'mediumWide'

}

Aspects of the speech still provoke debate on a number of fronts. One line of thought is that the focus by audiences and commentators on the “dream” portion of the speech and its message of tolerance and inclusiveness diverts attention from King’s pointed criticism of the government’s neglect of its African American citizens. There is little ambiguity in this and similar other lines in the first part of the speech: “America has given its colored people a bad check, a check that has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’” King also delivers an explicit warning that the march is just the first challenge to the status quo: “Those who hope that the colored Americans needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual.”

Other important figures in the movement who were on the stage with King delivered eloquent addresses of their own, including A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin and Walter Reuther, the noted labor leader. In this next clip, we highlight a speech that was not given at the march, or rather a speech that had to be changed at the last minute because of the storm of controversy it caused on the podium. This was SNCC chairman John Lewis’s impassioned delivery in which he directly confronted the Kennedy administration for its lack of commitment to enforcing civil rights law and particularly Robert F. Kennedy’s Justice Department for its refusal to pursue and prosecute racist assaults on activists and black Southerners. The original speech, written by a committee of SNCC activists, included the rhetorical question, “I want to know, which side is the federal government on?” Another dramatic line in the speech was this: “We will march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We shall pursue our own ‘scorched earth’ policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground — nonviolently.”

Patrick O’Boyle, archbishop of Washington and a Kennedy administration supporter and speaker that day, along with others in the coalition of unions and religious and civic leaders, threatened to withdraw from the march if changes weren’t made to the speech. The SNCC group that was attending the march initially resisted but was finally persuaded by A. Philip Randolph to make changes to the speech for the sake of march unity. But the episode still rankles SNCC members today, as both Courtland Cox and Joyce Ann Ladner attest in these interview excerpts from the Civil Rights History Project Collection.

{

shortName: '',

detailUrl: '',

derivatives: [ {derivativeUrl: 'rtmp://stream.media.loc.gov/vod/blogs/Lewis-...'} ],

mediaType: 'V',

autoPlay: false,

playerSize: 'mediumWide'

}

Both speeches are available for research by making an appointment with the staff of the Manuscript Division in the Library of Congress. This post is the fourth in a series that provides audiences with the perspectives and memories of organizers about the march through video and audio interviews in the collections of the American Folklife Center. The series accompanies the Library exhibition, “The March on Washington: A Day Like No Other,” which opens today. You can read more about the exhibition in this blog post from the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division.

August 26, 2013

Inside the March on Washington: “Our Support Really Ran Deep”

(The following is a guest post by Guha Shankar, folklife specialist in the American Folklife Center and the Library’s Project Director of the Civil Rights History Project, a Congressionally mandated documentation initiative that is being carried out in collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.)

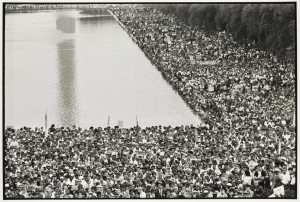

March on Washington crowd at the Reflecting Pool. Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos. Prints and Photographs Division.

Fifty years later, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom triggers different memories for participants and observers. It is safe to say that for most who witnessed it, in person or at home, the lasting images of the march are celebratory and triumphant. Popular accounts in the media reinforce those memories by centering on the determined and proud faces of thousands of ordinary people gathered peacefully in the nation’s capital to demand that the country live up to its founding principles of justice and equality. Similarly, Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech has become part of our collective consciousness, given the frequency with which it has been quoted, cited and replayed over the last 50 years.

Behind the scenes, organizers of the march and other notable figures in the movement experienced a complex range of emotions and confronted questions that became ever more pressing as the months and weeks leading up to the march dwindled to hours and minutes. Apprehension and nervousness were present and so too were elation and euphoria. Mostly hidden from public view were the tensions among and between the coalition of civic and religious leaders and front-line activists as to how the march could advance their goals and meet their demands for social change and justice.

This is the third in a series of posts that provides audiences with the perspectives and memories of organizers about the march through video and audio interviews in the collections of the American Folklife Center. The series accompanies the Library’s photo exhibition, “The March on Washington: A Day Like No Other,” opening on Wednesday, Aug., 28, 2013.

In the first clip, edited from interviews in the National Visionary Leadership Project collection, we hear the recollections of Rev. Joseph Lowery and Constance Baker Motley. Lowery was a Methodist minister in Mobile, Ala., when he became a civil rights activist in the 1950s. Along with King and other ministers, he founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), a leading civil rights organization. Lowery recalls the unease and uncertainty that he and other organizers felt before the march and their relief upon its peaceful conclusion.

Constance Baker Motley grew up in Connecticut and became a civil rights lawyer with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s (NAACP) Legal Defense Fund. She worked with Justice Thurgood Marshall and other lawyers to argue cases at the Supreme Court, including Brown v. Board of Education. She also traveled extensively across the country to meet with plaintiffs, gather evidence and work on local cases of civil rights abuses. In this interview, she reflects on the astonishment of movement leaders at the outpouring of feeling and involvement of so many “ordinary people” who participated in the march.

{

shortName: '',

detailUrl: '',

derivatives: [ {derivativeUrl: 'rtmp://stream.media.loc.gov/vod/blogs/March_...'} ],

mediaType: 'V',

autoPlay: false,

playerSize: 'mediumWide'

}

In the second clip, drawn from the Civil Rights History Project Collection, sisters Joyce Ann and Dorie Ladner reminisce about the events of August 28. The Ladners helped plan the march at its New York headquarters as representatives of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “Snick”), a national coalition of college-age activists, and were on the stage at the Lincoln Memorial for the march. For them, the days started off with a protest at the Justice Department over the case of colleagues in Americus, Ga., who had been jailed, weeks earlier, on false charges of sedition. The charges against SNCC’s Don Harris, John Perdew and Ralph Allen, and Congress of Racial Equality activist Zev Aelony carried a maximum sentence of death and SNCC chairman John Lewis’s speech later that day at the March criticized the Kennedy administration’s refusal to intervene in this and other deadly assaults on civil rights workers and community members in the South. Joyce Ann Ladner recalls the overwhelming numbers of marchers and also the presence of several notable figures on the stage such as Marlon Brando and Lena Horne.

{

shortName: '',

detailUrl: '',

derivatives: [ {derivativeUrl: 'rtmp://stream.media.loc.gov/vod/blogs/MarchD...'} ],

mediaType: 'V',

autoPlay: false,

playerSize: 'mediumWide'

}

These brief excerpts represent only a small sample of the documentation of the civil rights movement available at the American Folklife Center and other divisions in the Library of Congress.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers