Library of Congress's Blog, page 179

January 11, 2013

A Gift for President Karzai — and for You

On Thursday evening, a very nice gift was given, and received, in an ornate room at the U.S. Department of State. Afghan President Hamid Karzai was the recipient – on behalf of several libraries and research institutions in his nation – of a trove of digitized treasures from the Library of Congress and its associated World Digital Library, during a meeting with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

This “virtual repatriation” of materials largely found in the Library’s African and Middle Eastern Division (including poems and calligraphy by Mir’Ali Heravi, who worked in Afghanistan in the 16thcentury and manuscripts, rare books, maps, and photographs) was in turn part of a recent grant of $2 million by the Carnegie Corporation of New York to the World Digital Library (www.wdl.org).

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton greets Afghan President Hamid Karzai, joined by Carnegie Corporation of New York President Vartan Gregorian (left) and Librarian of Congress James H. Billington (right)

Now, here’s the part where you come in: the World Digital Library is waiting for you to dig into its manuscripts (and more manuscripts), maps, rare books (and more rare books), sound recordings, films, prints and photographs – all available free of charge – any time at all, 24 hours a day. And you can access it in any of seven languages. WDL, online since 2009, is a cooperative international project led by the Library of Congress.

It’s like being admitted to the antiquities rooms of the world’s great libraries, museums and archives (160 institutions from 77 nations have submitted their most exciting holdings to the World Digital Library) and just being allowed to leaf through the materials at will. Illustrations, pictures or maps can be zoomed in on to bring up amazing levels of detail.

So, dig in – what’s your favorite item in the World Digital Library?

Forever Free

Three-hundred-and-twenty-five words made up the first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation. So simple a start for what would become a pivotal document in our nation’s history – one that would also provide groundwork in passing the 13th amendment abolishing slavery.

Currently on view in the Library’s “The Civil War in America” exhibition through Feb. 18, the draft – in President Abraham Lincoln’s own hand – was really the first time he put forth a statement saying that slaves should be free, not just of their masters but living as free people in those states in rebellion during the war.

On July 22, 1862, Lincoln presented that draft to his cabinet. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and Attorney General Edward Bates advocated the document’s immediate release, but Secretary of State William Henry Seward advised the president to hold issuing the proclamation until a “more auspicious period,” which would come at the Battle of Antietam on Sept. 17, when Union forces stopped the Confederate advance into Maryland. On Sept. 22, Lincoln put forward an official preliminary proclamation.

For the first time, the Library’s first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation was brought together with two artifacts associated with the important document for a photo shoot and article in this month’s issue of Smithsonian Magazine. An inkwell used by Lincoln as he formulated the proclamation in the telegraph room of the War Department is in the collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. And, a pen that Lincoln used to sign the final proclamation resides with the Massachusetts Historical Society.

For the first time, the Library’s first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation was brought together with two artifacts associated with the important document for a photo shoot and article in this month’s issue of Smithsonian Magazine. An inkwell used by Lincoln as he formulated the proclamation in the telegraph room of the War Department is in the collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. And, a pen that Lincoln used to sign the final proclamation resides with the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Inspired by the Smithsonian story, the Library produced a piece on the three objects and their significance in transforming a nation. You can see it here.

[media player not shown]

The final draft of the Emancipation Proclamation was signed Jan. 1, 1863, but it ultimately was a wartime measure that would not ensure freedom after the war. The only way to truly eliminate the institution of slavery was an amendment to the United States Constitution, which Lincoln successfully lobbied the U.S. Congress to adopt. The 13th Amendment was ratified on Dec. 6, 1865.

“I never in my life felt more certain that I was doing right than I do in signing this paper,” said Lincoln of the proclamation, according to the Smithsonian story. “If my name goes into history, it will be for this act, and my whole soul is in it.”

January 9, 2013

InRetrospect: December Blogging Edition

Library curators and staff decked the blogs in December with a variety of posts. Here are some highlights.

In the Muse: Performing Arts Blog

A Miro on Which to Dwell

The Miro Quartet pays homage to Schubert and Stradivarius

The Signal: Digital Preservation

Why Does Digital Preservation Matter

Bill LeFurgy talks about the importance of digital stewardship

Picture This: Library of Congress Prints & Photos

Puck Cartoons: “Launched at Last!”

More than 2,500 color cartoon illustrations published in Puck magazine

From the Catbird Seat: Poetry & Literature at the Library of Congress

A Grimm Beginning

The 200th anniversary of the publication of the first volume of “Grimms’ Fairy Tales” is celebrated

Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business

Greatest Inventions: 2012 and 1913 Editions

Jennifer Harbster asks what are the top inventions of 2012.

In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress

Unusual Laws: The Tudor Vermin Acts

A bounty is placed on nuisance animals.

Teaching with the Library of Congress

It’s Snowing: Plowing Ahead with Primary Sources from the Library

Ann Savage looks at the lesson in snow.

Copyright Matters: Digitization and Public Access

Getting Ready for Data Capture: Sorting Out the Details in the Catalog Cards

Mike Burke talks about work being done to capture data from pre-1978 Copyright records.

January 8, 2013

Inquiring Minds: An Interview with British Research Council Fellow Maria Shmygol

The following is a guest post by Jason Steinhauer, program specialist in the Library’s John W. Kluge Center.

Maria Shmygol

In 2012, the John W. Kluge Center welcomed 28 promising young scholars from the United Kingdom to conduct research at the Library of Congress. The scholars – all currently pursuing doctorate degrees – are funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the Economic and Social Research Council, which have been collaborating with the Library since 2006 to provide short-term opportunities for scholars based in the U.K.

British Research Council Fellow Maria Shmygol talks about her research and her three-month tenure at the Kluge Center.

Q: Tell us about yourself and your research.

A: I’m from the University of Liverpool, and I’m in my final year of my doctorate, which is about performing “sea change” in early modern literature and drama. I’m exploring how developments in commerce, navigation and exploration impacted the early modern imagination and the representation of the sea as a cultural, historical and aesthetic space on the Renaissance stage in plays like “The Tempest,” for example.

Q: How did you get interested in the Renaissance and the sea?

A: I started specializing in the Renaissance quite early during my undergraduate program. I developed an interest in Renaissance drama during my masters’ year, when I also became interested in cartography. I’ve always liked old maps, and when I started coming into contact with more, I couldn’t stop! I became very interested in how cartographers were representing maritime space. The study of images on maps got me interested in other kinds of illustrations that have pictorial articulations of marine creatures. There’s something interesting in exploring the anxiety to fill the emptiness of the sea with some sort of recognizable images.

Q: How is it that you came to the Kluge Center?

A: I found out about the program on the AHRC website. I thought it would be a great experience to be at this library, have my own space to work, be immersed in the collections and have absolutely no distractions at all. I thought I’d apply to work with the extensive collections that the Library has in the Renaissance period.

Q:How has your experience been?

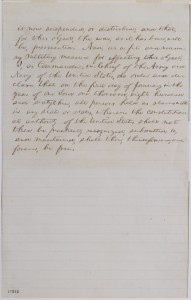

Image from Ingrid Faust’s six-volume edition of “Zoologische Einblattdrucke und Flugschriften vor 1800.”

A:It’s been great. I’ve had time to continue my work uninterrupted. I’ve talked with experts who’ve had really interesting things to share with me, especially in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Mark Dimunation, the head of Rare Books, had a batch of lettering and calligraphy manuals, one of which had images of mermaids and tritons made of calligraphy flourishes. That’s not something I’ve come across before, so it was quite an exciting find. He also introduced me to Giovanni Battista Bracelli’s “Bizzarie di Varie Figure,” a collection of unusual sketches by a little-known Florentine artist, which is one of only two surviving copies worldwide. One of the sketches looks a lot like a Florentine fountain I’m writing about, so I’m interested in whether the artist would possibly have seen that statue and then drawn the sketch.

Q: Tell us also about this book that you’ve had at your desk throughout your fellowship.

A: This is a part of Ingrid Faust’s six-volume edition of European early modern zoological pamphlets and broadsheets. It has quite an extensive collection of animal prints and pretty much covers every kind of animal, including sea monsters. One example is a French pamphlet about an anthropomorphic sea monster. The entry has some references to some other similar pamphlets that were previously unknown to me. I’ve tracked down such pamphlets with the help of the references in this book, and after emailing the Royal Library in Denmark, I was able to procure a PDF of a rare German pamphlet that deals with a similar kind of monster. I’m looking forward to translating that when I get home.

Q: Apart from translating German sea monster pamphlets, what are your future plans?

A: I’ll be applying for post-doctoral positions and teaching jobs and hoping to develop some new research projects. Maybe I’ll even return to the Library of Congress as a Kluge Fellow!

Q: Any final thoughts as you head home?

A: This has been a really great experience. The staff here are really, really helpful. It’s been amazing to have so many people that know so much about everything! To be here among the Kluge scholars every day has been wonderful, and I would encourage anyone to apply for this fellowship – it’s been an amazing three months.

January 4, 2013

Update on the Twitter Archive at the Library of Congress

(The following is a guest post from the Library’s Director of Communications, Gayle Osterberg.)

An element of our mission at the Library of Congress is to collect the story of America and to acquire collections that will have research value. So when the Library had the opportunity to acquire an archive from the popular social media service Twitter, we decided this was a collection that should be here.

In April 2010, the Library and Twitter signed an agreement providing the Library the public tweets from the company’s inception through the date of the agreement, an archive of tweets from 2006 through April 2010. Additionally, the Library and Twitter agreed that Twitter would provide all public tweets on an ongoing basis under the same terms.

The Library’s first objectives were to acquire and preserve the 2006-10 archive; to establish a secure, sustainable process for receiving and preserving a daily, ongoing stream of tweets through the present day; and to create a structure for organizing the entire archive by date.

This month, all those objectives will be completed. We now have an archive of approximately 170 billion tweets and growing. The volume of tweets the Library receives each day has grown from 140 million beginning in February 2011 to nearly half a billion tweets each day as of October 2012.

The Library’s focus now is on addressing the significant technology challenges to making the archive accessible to researchers in a comprehensive, useful way. These efforts are ongoing and a priority for the Library.

Twitter is a new kind of collection for the Library of Congress but an important one to its mission. As society turns to social media as a primary method of communication and creative expression, social media is supplementing, and in some cases supplanting, letters, journals, serial publications and other sources routinely collected by research libraries.

Although the Library has been building and stabilizing the archive and has not yet offered researchers access, we have nevertheless received approximately 400 inquiries from researchers all over the world. Some broad topics of interest expressed by researchers run from patterns in the rise of citizen journalism and elected officials’ communications to tracking vaccination rates and predicting stock market activity.

Attached is a white paper [PDF] that summarizes the Library’s work to date and outlines present-day progress and challenges.

December 27, 2012

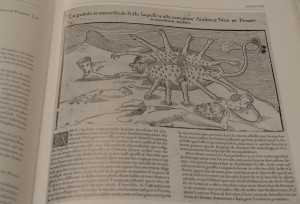

Civil War Cartography, Then and Now

During the Civil War, cartographers invented new techniques to map the country and the conflict more accurately than ever before in the nation’s history. Since then, cartographic technology has evolved in ways never imagined, but many basic elements of mapmaking remain the same. The following is an article, written by Jacqueline V. Nolan and Edward J. Redmond of the Library’s Geography and Map Division, that is featured in the November-December 2012 issue of the Library’s new magazine, LCM, and highlights progress in cartography since the Civil War.

A sketch map of the battlefield of Gettysburg, 1863, by Jedidiah Hotchkiss combined with U.S. Geological Survey’s satellite-derived map with attributes from the National Hydrography dataset

Mapmaking has been revolutionized since the Civil War. Comparatively speaking, creating a map using modern technologies little resembles yesteryear’s methodology. Yet, many consistencies in mapping prevail from one era to the next. The basic elements of map production still consist of determining geographic coordinates and reference points, construction of projections, design, compilation, drafting and reproduction.

During the Civil War era, the production of a finished map was a protracted and labor-intensive process that involved a variety of skills and crafts. It began with a land survey or field reconnaissance by a military topographer—often on horseback—with sketchbook in hand. Rivers, roads and significant landscape features were rapidly drawn in pencil on pages marked with grid lines. Direction was determined by compass bearings, and distance was tracked by pacing on foot or horseback. Data from these field sketches were later transferred to larger sheets notated with geographic coordinates to produce a composite manuscript map of an area or region at a particular scale.

If a map was to be reproduced for wider dissemination, copies could be furnished in a variety of formats. Various photographic methods were devised during the war to reproduce manuscript field surveys quickly, in limited numbers for field commanders. Woodcut engraving was favored by newspapers, which published maps almost daily to help war families locate the remote places described in the letters they received from their loved ones at the front. Official and commercial maps were engraved or lithographed, and then hand-colored. Each of these processes required trained craftsmen as well as specialized tools and equipment. The copperplate engravers who worked for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, for example, were primarily German craftsmen recruited especially for the detailed engraving required by that agency.

Current trends in mapping allow for multiple layers of data to be combined by one cartographer using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) software on a desktop computer. GIS has become a useful tool for research using spatial data analysis and is being applied to many fields of study, wherever geography can be modeled.

U.S. Geological Survey’s satellite- derived map of Gettysburg, 2007

U.S. Geological Survey’s satellite- derived map of Gettysburg, 2007

Creating a map using GIS is also a layered process. Using multiple sources of data, such as field data, research statistics, real-time data, and so on, information can be overlaid on a base map representing a geographic area of interest such as a Civil War battle site. Base layers may be characterized as either a pixilated, raster format, derived from remote-sensing imagery, or as a vector file, which depicts geography as points, lines and polygons.

Map specifications such as projection, scale, and key details are determined in this initial phase. Data is standardized to ensure attribute- matching with the base layer prior to performing data analysis.

GIS software packages include toolkits containing many devices for analysis and editing. Metadata is compiled to document specific information about the GIS project, such as source data, attribute definitions, or algorithms used for statistical computations. Analysis is the primary end-product of a GIS project, though a cartographic rendering may be created such as a paper map, a web-based application for visual interpretation on a computer screen, or applications software for display on mobile devices (apps).

MORE INFORMATION

“Re-imagining the U.S. Civil War: Reconnaissance, Surveying and Cartography” (webcast: Part I, Part II)

Hotchkiss Map Collection

Download the November-December 2012 issue of the LCM in its entirety here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

December 24, 2012

Yes, Virginia, There is a Santa Claus

I remember the moment I found out that jolly old St. Nick was more an idea than a physical person shimmying down a chimney to deposit presents underneath the tree. First clue, we didn’t have a fireplace.

Carol Highsmith / Prints and Photographs Division

I can’t remember exactly how old I was, probably elementary school age. The night before Christmas I could never fall asleep, which is probably the way of most kids. I remember hearing noises coming from the far side of the house and the screen door off the carport slamming from time to time. As I inched closer to the bedroom door to investigate the ruckus, I remember hearing my dad ask my mom – not quietly enough apparently – where she wanted him to put the presents.

The thing is, I can’t remember being too terribly upset. Christmas was, and still is, wonderful at my house. It’s a time of happiness, silliness, love and giving.

I think Santa still lives on in us, regardless of whether you actually believe – he appeals to the hope and imagination of young and old alike.

Perhaps this editorial for the Sept. 21, 1897, issue of the New York Sun says it best.

Eight-year-old Virginia O’Hanlon wrote a letter to the editor of The New York Sun, and the quick response was printed as an unsigned editorial. The work of veteran newsman Francis P. Church has since become history’s most reprinted newspaper editorial, appearing in part or whole in dozens of languages in books, movies and other editorials, and on posters and stamps.

“Yes Virginia, there is a Santa Claus. He exists as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist, and you know that they abound and give to your life its highest beauty and joy. Alas! How dreary would the world be if there were no Santa Claus. …. There would be no childlike faith then, no poetry, no romance to make tolerable this existence.

“Nobody sees Santa Claus, but that is no sign that there is no Santa Claus. The most real things in the world are those that neither children nor men see. … Nobody can conceive or imagine all the wonders there are unseen and unseeable in the world.

“A thousand years from now, Virginia, nay 10 times 10,000 years from now, he will continue to make glad the heart of childhood.”

Happy holidays to you and yours!

December 20, 2012

The Sensei from Sioux City

Today marks 19 years since the passing of one of the world’s great management thinkers—W. Edwards Deming.

W. Edwards Deming in Japan, around the time he revolutionized Japanese manufacturing (courtesy W. Edwards Deming Institute)

After World War II, the U.S. did something remarkable in the history of war – it helped its friends and even its former foes get back on their feet economically. In Europe, that was accomplished through the Marshall Plan – but in Japan, where the U.S. also gave broad counsel, one man had a singular impact: Ed Deming.

Born in Sioux City, Iowa and reared in Iowa and Wyoming, Deming was officially a statistician and college professor, and he was sent to Japan post-war to give his expertise to the U.S. allied command and help the Japanese government set up a census.

But he had studied work processes from a statistical point of view for years and had come to some interesting conclusions – essentially, that quality with the goal of satisfying customers and even employees must govern production decision-making, and ultimately costs less than trying to sell lower-quality goods. In that war-torn nation lacking a broad industrial base, Deming in 1950 was invited by a Japanese scientists’ and engineers’ group to give a talk – the first of many – that set the stage for a Japanese resurgence in electronics, automobiles and other produced goods. Later, he authored many books and taught at several U.S. universities.

Deming’s teachings, which came to be known as Total Quality Management or TQM (and originated to address production-style workplaces) have been summarized as 14 points:

1. “Create constancy of purpose towards improvement.” That is, plan for the long term instead of reacting, short-term.

2. “Adopt the new philosophy.” Everyone in the workplace – including the management – understands and lives by the philosophy established for that workplace.

3. “Cease dependence on inspection.” If statistical variation is reduced, inspection for product defects loses importance because there will be few, or no, defects.

4. “Move towards a single supplier for any one item.” Multiple suppliers increase the potential for statistical variation and defects.

5. “Improve constantly and forever.” A workplace must constantly strive to reduce variation.

6. “Institute training on the job.” If people aren’t sufficiently trained, they will not all work the same way, and this will introduce variation.

7. “Institute leadership.” Deming made a distinction between leadership and supervision, which he defines as quota- and target-based.

8. “Drive out fear.” Deming believed workers would act in an organization’s best interest if they would not be punished or demoted for pointing out problems or telling uncomfortable truths.

9. “Break down barriers between departments.” In Deming’s analysis, customers are not just people outside the organization – customers include other departments within a workplace.

10. “Eliminate slogans.” Deming felt that posting slogans or exhortations was not nearly as effective in improving a workplace as finding out where, in that workplace’s processes, the bugs were, and removing them.

11. “Eliminate management by objectives.” Deming disliked production targets, saying they led to delivery of poor-quality goods.

12. “Remove barriers to pride of workmanship.” Satisfied workers make quality products.

13. “Institute education and self-improvement.”

14. “The transformation is everyone’s job.”

Deming remains one of the most revered business thinkers of our time – and his papers are in the Manuscript Division here at the Library of Congress.

The W. Edwards Deming Institute entertains applications for grants to aid students or authors in conducting their research using that Library of Congress collection.

Trending: The End of the World

(The Maya calendar has generated a lot of buzz about the impending end of the world as we know it, on Dec. 21, 2012. The following is an article written by colleague Audrey Fischer from the November-December 2012 issue of the Library’s new magazine, LCM, highlighting what’s “trending” in the news, on the web and in social media.)

An Interpretation of the Mayas’ “Long Count” calendar, which began with the ritual date of Maya creation, Aug. 11, 3114 B.C., shows its end on Dec. 21, 2012.

Don’t delay your Christmas shopping just yet. Nothing in what is known of Maya writing supports this conjecture.

The Dresden Codex / Rare Book and Special Collections Division

That reassuring word comes from art historian and epigrapher Mark Van Stone. In his book, “2012: Science & Prophecy of the Ancient Maya,” he takes a scientific and archaeological-focused look at what the ancient Maya actually believed. Van Stone, who spoke at the Library of Congress in October, concludes that end-of-the world prophecies are the creations of our current society, with little basis in what is known about the Maya and their beliefs.

David Stuart, the foremost expert on Maya hieroglyphs, agrees. In his book, “The Order of Days: The Maya World and the Truth about 2012,” Stuart reveals that by deciphering dates and information carved into stone stelae (monuments), one may postulate that the full Maya calendar accounts for nearly 72 octillion years. Stuart delivered the fifth Jay I. Kislak lecture on this topic at the Library last year. (This lecture is now available as a webcast.)

In addition to establishing the lecture series, the Jay I. Kislak Foundation donated to the Library an important collection of books, manuscripts, historical documents, maps and art of the early Americas. A permanent rotating exhibition of materials from the Kislak Collection, “Exploring the Early Americas,” opened in December 2007 and remains on view in the Thomas Jefferson Building.

A handful of Maya artifacts were recently rotated into the “Early Americas” exhibition in a section titled “The Heavens and Time: 2012 Phenomenon.”These include a facsimile edition of the Dresden Codex—the most comprehensive source of the Maya calendar system and astronomy—and the oldest known book written in the Americas.

Download the November-December 2012 issue of the LCM in its entirety here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

December 19, 2012

Inquiring Minds: Scholar Manuel Castells on Social Movements

The following is a guest post by Jason Steinhauer, program specialist in the Library’s John W. Kluge Center, as part of the Inquiring Minds series.

The revolutionary wave of demonstrations, protests and wars known collectively as the Arab Spring has spanned Algeria to Oman, covering a distance of 3,400 miles and toppling regimes that governed for a generation. The use of social media by demonstrators to organize and communicate has raised new questions about social movements in the Internet Age.

The revolutionary wave of demonstrations, protests and wars known collectively as the Arab Spring has spanned Algeria to Oman, covering a distance of 3,400 miles and toppling regimes that governed for a generation. The use of social media by demonstrators to organize and communicate has raised new questions about social movements in the Internet Age.

Scholar Manuel Castells addressed these questions in a lecture August 23 at the Library of Congress John W. Kluge Center, titled “Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age.” The talk is now available as a webcast.

Castells is among the world’s leading sociologists: an author of 26 books, an advisor to foreign governments and the 2012 winner of Norway’s prestigious Holberg Prize. This summer he resided at The John W. Kluge Center as the Kluge Chair in Technology and Society, continuing his research on social movements in the Internet Age. These unexpected movements have sprung up across the world, not solely in the Middle East, but also Iceland, Tunisia, Chile and the United States. Demonstrations have occurred in thousands of cities.

Castells sees a pattern common to these movements. The trigger, he says, is anger; the repressor is fear. In each movement, fear was overcome by individuals sharing in the outrage together online.

“We are all trembling,” Castells said in the lecture. “When we cannot hold hands in the street, we hold hands on the internet.”

Once fear is overcome, Castells theorizes, mobilization then ensues. Mobilization begets enthusiasm, which breeds hope that things can be different. (Hence the title of his new book, “Networks of Outrage and Hope.”)

The shape of these recent social movements is defined by the Internet. Castells reminds us that the Internet is an “old” technology, first deployed in 1969. It does not create social movements. Rather, today’s social movements are defined by the new forms of the Internet, specifically the shift from mass communication to mass self-communication. Mass self-communication reaches everywhere and operates independently of ruling authorities. These movements are leaderless. They do not need control centers. And they are impervious to destruction. As Castells says, you may kill the messenger, yet the message lives on in the network. He describes the networks as “rhizomatic”: they are underground, they emerge, they go down, and are connected all the time.

Ultimately the movements coalesce by occupying the urban space. On the Internet, you connect but you do not touch. In the city, together, there is a moment of re-formation. By forming on the internet first, though, as opposed to the street, the same movement that failed in Egypt in 2008 can succeed in Egypt in 2011.

Castells cautions us to be careful in evaluating the “success” of these movements. Social movements aim to change the way we think—and in the mind, he says, is where power truly originates, for thoughts dictate actions. Castells points out that before the Occupy movement, in 2009, Pew Research Center found that 45 percent of Americans thought income inequality was the defining conflict in American society. In 2011, 70 percent thought so. While that change may not be felt in the next election, it will be felt in the next generation. Castells reads a tweet from Tahrir Square to re-enforce his point:

“We have brought down the wall of fear. You brought down the wall of our house. We’ll rebuild our homes. But you will never build again that wall of fear.”

Trending in Washington this month are a diverse group of think tank events on the topics of the Arab Spring and regulating the internet. As a society we are still grappling to understand the full ramifications of the Internet age we have ushered in. Scholarship will be critical. Bringing enquirers to ask questions and offering a space for the transfer of knowledge and informed discussion is what the Kluge Center aims to do.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers