Library of Congress's Blog, page 181

November 13, 2012

InRetrospect: October Blogging Edition

Here’s a sampling of some of the highlights in the Library’s blogosphere from October.

Teaching with the Library of Congress

The Women’s Suffrage primary source set is featured.

In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress

Welcome to Our New Front Door: A Revamped Homepage

The Law Library of Congress gets a homepage facelift.

Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business

Jennifer Harbster takes a look at bats.

From the Catbird Seat: Poetry & Literature at the Library of Congress

Poetry Center Director Rob Casper talks about a Poetry Out Loud experience.

Picture This: Library of Congress Prints & Photos

From Player Portraits to Baseball Cards

Highlighted are photographer Paul Thompson’s 1910 baseball player portraits.

The Signal: Digital Preservation

If You Can’t Open It, You Don’t Own It

Writer and blogger Cory Doctorow discussed libraries, ebooks and beyond at an October event.

In the Muse: Performing Arts Blog

Five Questions: Xavier Zientarski, Intern

Intern from Montgomery College in Maryland talks about his time working in the Music Division.

November 7, 2012

Waste Not, Want Not

While the Civil War imposed hardships on both sides, the South found it particularly difficult to adapt to new realities of daily life. The blockade of Southern seaports and the prohibition of trade with the North quickly depleted food supplies throughout the Confederacy. Farmers became soldiers, and a large percentage of crops were used to feed the troops in the field.

However, these deprivations forced Southerners into resourcefulness. Just as they devised new weapons in fighting the enemy, they also developed ways to fight disease, hunger and food spoilage. Cooks and homemakers were driven to invent substitutes for the most basic foods and beverages.

“Confederate Receipt Book.” Richmond, Virginia: West & Johnston, 1863. Confederate States of America Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

“The Confederate Receipt Book: A Compilation of Over One Hundred Receipts, Adapted to the Times” (Richmond, West & Johnston, 1863) was compiled from practical receipts (or recipes), which had appeared in Southern newspapers since the beginning of the war. The tome will be on view in “The Civil War in America” exhibition opening Nov. 12.

The only cookbook printed in the South during the war, the “Confederate Receipt Book,” contains recipes for apple pie without apples, artificial oysters, slapjacks, peas pudding and several different ways to make bread.

The book also provided tips for preventing waste, suggestions for substitutions and instructions for economizing and doing without. Those without money or transport would have welcomed suggestions for making bad butter usable or fashioning a lamp wick out of a clean, cotton stocking. Since salt was virtually impossible to buy, a method of curing bacon with precious little salt was extremely useful. In an effort to fend off insect infestation in such cured meats, there was even a suggestion to “prevent skippers,” the nickname of that time for insects such as locusts and grasshoppers.

According to the “Receipt Book,” a substitute for a splendid cup of coffee was described as “ripe acorns, washed and dried, parched until they opened and then roasted with a little bacon fat.” Cream for the coffee was the white of an egg, beaten to a froth, and mixed with a bit of butter.

Ladies, unable to purchase new frocks, appreciated the hints for altering, cleaning and refreshing worn garments, as well the tip of turning petticoats back to front to make them last twice as long.

Home remedies set forth in the “Receipt Book” included cures for such common ailments as chills, corns, warts and asthma.

According to Constance Carter, head of the Science Reference Section in the Library’s Science, Technology and Business Division, one can only assume this compilation was received as gratefully by homemakers in the 1860’s as books on rationing, thrift and wartime meals were during subsequent wars.

The compilation is mentioned more than once in the Science Reference Section’s “Food Thrift: Scraps from the Past” webcast as are many of the trials and tribulations faced by the blockaded South.

You can read about other items in “The Civil War in America” exhibition in these previous blog posts:

November 6, 2012

Stop the Presses!

With Election Day upon us and votes soon to be counted, the nation waits with bated breath to see who our next president will be. Here in D.C., crowds gather in local bars and pubs, as if it were Monday Night Football, to catch the news of which candidate won what state and taking bets on who will be elected president.

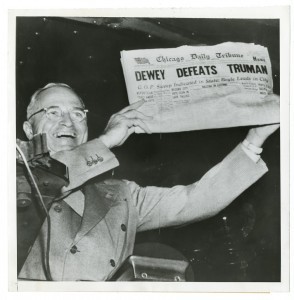

But history has shown that it might be better to hedge those bets. Case in point: in the 1948 election pitting incumbent President Harry S. Truman against Republican Thomas E. Dewey, most predicted that Dewey would win. In fact, The Chicago Daily Tribune was so sure of his victory, they printed the front-page headline, “DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN,” that Tuesday before any polls closed. According to the paper’s website, a printers’ strike on election night forced editors to go to print hours before the normally scheduled time. However, as the night wore on and reports filtered in, it became clear that Truman would again be president.

The photograph with Truman raising aloft the newspaper with its headline has become one of the most famous newspaper photos of that century. The Library holds a copy of that issue, dated Nov. 3, 1948, in its Serial and Government Publications Division.

Truman won the election by winning three big states: California, Ohio and Illinois. Dewey won New York, Pennsylvania and Michigan, but it was too little too late. The president managed to carry 24,105,812 popular votes to Dewey’s 21,970,065.

According to political experts, while Truman may have been unpopular in the polls, his aggressive campaign style attributed much to his success, compared to Dewey, who appeared complacent and distant in his approach.

(This is the final post in a series of posts featuring presidential campaign items from the Library’s collections. Read the others here, here and here.)

November 2, 2012

Protocol for One and All

Etiquette. We love to make fun of it – from the character Rose Maybud in Gilbert & Sullivan’s “Ruddigore” who is constantly consulting her tiny etiquette book (“It’s manners out-of-joint, to point!”) to Vincent Price lecturing his creation “Edward Scissorhands” in the movie of the same name: “Etiquette tells us just what is expected of us and guards us from all humiliation and discomfort.”

But it’s no joke if you need access to solid protocol information to accomplish something, whether it’s planning a wedding, making sure the international guests aren’t needlessly offended or writing an appropriate condolence note.

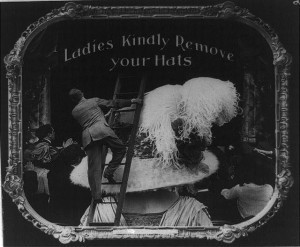

Then it was hats; now, texting and talking in theaters.

This week marked the passing of an etiquette expert who has gotten me through many a vexing question — Letitia Baldrige.

A couple of lifetimes ago, when I did PR for a financial firm headed by a Brahmin who was probably born knowing which fork to use and in what order, I was handed the task of throwing a launch party for a new facility we were opening – three states away. Lots of honchos were involved. Everything had to be spot-on.

I ran right out and bought my own copy of “Letitia Baldrige’s Complete Guide to Executive Manners.” It saved me then, and has on several occasions since. Yes, I’ve committed any number of solecisms since then, but I like to think there have been fewer since I got Tish on my team.

So let me propose a toast: to Letitia Baldrige, who has helped me move through life with a minimum of justified muttering. Remember, when you toast, raise your glass and move it through the air a bit, but don’t clink it against someone else’s …

It’s manners out-of-sync, to clink.

October 31, 2012

Inquiring Minds: An Interview with John Witte

(The following is a guest post by Jason Steinhauer, a program specialist in the Library’s John W. Kluge Center, as part of the blog series, “Inquiring Minds.”)

Legal scholar John Witte served as the recent Cary and Ann Maguire Chair in Ethics and American History. Author of 220 articles, 15 journal symposia, and 26 books, Witte has turned his attention to faith-based family law systems in the West, and in particular Islamic law, Sharia. His lecture on the topic is still scheduled at the Library of Congress for tomorrow, Nov. 1. You can read more about it here.

Q: Tell us about your lecture on November 1st, and the importance of this topic.

A: I’m exploring issues on the frontier of family law. Of particular interest are faith-based family systems, based on Sharia, Halacha and Canon Law, that are operating quietly in many Western countries, including the United States. The question of the legitimacy and authority of these faith-based family law systems is lurking just over the horizon. It’s a question that is going to explode, especially when an issue regarding Sharia captures public imagination.

Q: What do you mean by ‘explode?’ What is the trend up to now?

A: One of these days, the federal courts will get a hot case of a Muslim polygamist challenging the constitutionality of a state anti-bigamy statute, or an American Imam defending his declaration of fatwa on someone who defies the family norms of Sharia. Eventually one of those cases is going to hit the national and international airwaves. This has happened recently in other common law countries. In the United States, the issue of faith-based family laws, especially the use of Sharia, might soon become as hot a constitutional topic as same-sex marriage, abortion or contraception in decades past.

Q: What can scholarship bring to this discussion?

A: Scholars can and should widen the conversation by encouraging antagonists to look beyond the particularly inflamed issue that’s before the public media. Scholars can give comparative and historical reflection on what other legal systems past and present have done. What I’m trying to do in scholarship is lay some of those historical and analogical resources on the table and help people think about the issues with those broader matrices in mind.

Q: What role has the Library played in helping you with your scholarship?

A: The Library is a scholar’s paradise. There are resources bundled here in such concentration that you’d be hard-pressed to find anywhere else in the world. I’ve been able to pull out 10 different versions of the Talmud or of a Church Father’s writings, wonderful 12th- to 15th- century canon law texts and learned theological treatises on marriage and the family. I’ve been able to do really deep primary research on sources that are not accessible through reliable digital means. I discovered a remarkable diary of a late 12th century monk who had traveled with the crusaders and provided a detailed account of Muslim polygamy and offered his own critical reactions to the practice. All this has been a wonderful treat.

Q: Who do you hope comes to the Library to hear this lecture on November 1?

A: All people of good will interested in the future of marriage and family, interested in the contest between religious freedom and sexual freedom, and interested in the relationship between Islam and the West will, I hope, find this topic interesting. I hope we can have the kind of serious conversation that the topic deserves, and that is one of the hallmarks of Kluge Center events.

Mapping Slavery

Edwin Hergesheimer. “Map Showing the Distribution of the Slave Population of the Southern States of the United States Compiled from the Census of 1860.” Washington: Henry S. Graham 1861. Geography and Map Division.

According to the 1860 census, the population of the United States that year was 31,429,891. Of that number, 3,952, 838 were reported as enslaved. The 1860 census was the last time the federal government took a count of the Southern slave population. In 1861, the United States Coast Survey issued two maps of slavery based on the census data: the first mapped Virginia and the second mapped Southern states as a whole.

The landmark map of the Southern states provided a graphic breakdown of those census returns, specifically focusing on slave population per county as a percentage of the total population in the southern portion of the nation. Using statistical cartography, low percentages were shown in light grey while higher percentages were illustrated using more intense shading. This provided a dramatic representation of slavery across the region. The counties along the Mississippi River and in coastal South Carolina show the highest percentage of slaves, while Kentucky and the Appalachians show the lowest.

According to Susan Schulten, history department chair at the University of Denver, the map reaffirmed the belief of many in the Union that secession was driven not by a notion of “states’ rights,” but by the defense of a labor system. A table at the lower edge of the map measured each state’s slave population, and contemporaries would have immediately noticed that this corresponded closely to the order of secession. However, the map also illustrated the degree to which entire regions – like eastern Tennessee and western Virginia – were largely absent of slavery and thus potential sources of resistance to secession.

(Schulten spoke about the map at a Library of Congress symposium last year. You can view the webcast here.)

The Southern stages slavery map is a featured item in the “The Civil War in America” exhibition, opening next month, and has never before been displayed by the Library to the public.

This map was, by some accounts, consulted by Abraham Lincoln throughout the course of the Civil War. It even appears in the famous 1864 painting of the president and his cabinet, titled “First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Lincoln,” by artist Francis Bicknell Carpenter — a print of which is in the Library’s collections.

Next Wednesday’s post will be the final spotlight on items from the exhibition. You can read about others in these previous blog posts:

October 26, 2012

Growing a Library

(The following is an article from the September-October 2012 issue of the Library’s new magazine, LCM, discussing how the Library acquires its collections.)

By Audrey Fischer

Beginning with a purchase of 740 books by Congress in 1800, the Library of Congress collection has grown to nearly 152 million items. But purchase is just one acquisition method that the nation’s library uses to build its unparalleled collection in all formats, on myriad subjects, from all over the world.

On April 24, 1800, President John Adams approved an act of Congress establishing the Library of Congress. The legislation also appropriated $5,000 “for the purchase of such books as may be necessary for the use of Congress.”

The bulk of the Library’s nascent collection of 740 volumes was purchased from London booksellers Cadell & Davies in June 1800. Fourteen years later, the British would burn those volumes—and several thousand additional tomes—when they pillaged the U.S. Capitol during the War of 1812.

The collection got a big boost when former president Thomas Jefferson agreed to sell his personal collection of 6,487 volumes to Congress in 1815 to rebuild the congressional library. Congress appropriated $23,950 for that historic purchase.

But perhaps the biggest boon to the Library’s collection came on July 8, 1870, when President Ulysses S. Grant approved an act of Congress that centralized all U.S. copyright registration and deposit activities at the Library of Congress. Copyright deposits—copies of work submitted for copyright registration—make up the core of the collections, particularly in the Library’s holdings of maps, music, motion pictures, prints and photographs. Last year, the Copyright Office forwarded more than 700,000 copies of works with a net value of $31 million to the Library’s collections.

In addition to purchase and copyright deposit, materials are acquired by gift, exchange with other libraries in the U.S. and abroad, transfer from other government agencies and through the Cataloging in Publication program (a pre-publication arrangement with publishers).

On average, the Library acquires about 2 million items annually. Some 22,000 items arrive each working day, from which about 10,000 items are added to the collections—according to guidelines outlined by the Library’s collection policy statements (and in consultation with Library specialists and recommending officers).

Items not selected for the Library’s collections are made available to other federal agencies and are then available for donation to educational institutions, public bodies and nonprofit tax-exempt organizations through the Surplus Books Program.

Download the September-October 2012 issue of the LCM in its entirety here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

MORE INFORMATION

October 25, 2012

Terminology in Office

(This is the third in a series of posts featuring presidential campaign items from the Library’s collections. Read the others here and here.)

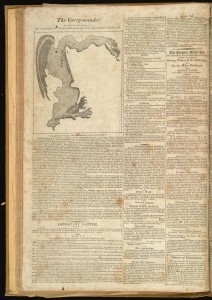

“The Gerrymander. A New Species of Monster.” Boston Gazette, March 26, 1812. Serial & Government Publications Division

Every election year, as candidates go head to head during their campaigns, a new wave of vocabulary is born. Political idioms that have found their way into our lexicon include POTUS, left-wing, right-wing, working class, bipartisan, pork barrel, pundit, swing state and the list goes on and on.

So, what’s the genesis of the jargon? Let’s take a look at one:

In 1812, Jeffersonian Republicans forced through the Massachusetts legislature a bill rearranging district lines to assure them an advantage in the upcoming senatorial elections. Although Gov. Elbridge Gerry had only reluctantly signed the law, a Federalist editor is said to have exclaimed upon seeing the new district lines, “Salamander! Call it a Gerrymander.” A political cartoon-map delineating these redrawn electoral districts first appeared in the Boston Gazette for March 26, 1812. Therein lies the origin of the modern day term “gerrymandering.”

The Library also holds the original woodblocks from the 1812 Boston Gazette cartoon “The Gerry-Mander.”

“Words Like Sapphires”

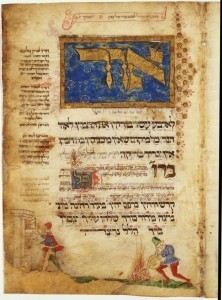

(The following is a guest article written by my colleague Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library’s staff newsletter, The Gazette, about today’s opening of a new exhibition celebrating the 100th anniversary of the institution’s Hebraic collection.)

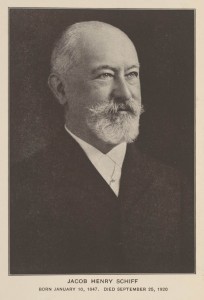

A simple label inside thousands of rare books bears witness to the origins of one of the great collections of Hebrew material in the world: “Deinard Collection Presented by Jacob H. Schiff.”

Beginning next week, the Library of Congress will celebrate the 100th anniversary of its Hebraic Collection – started with a gift from Schiff in 1912 – with a five-month exhibition that explores the Jewish experience through the written word.

“Words Like Sapphires: 100 Years of Hebraica at the Library of Congress, 1912-2012” opens on Oct. 25 in the South Gallery of the Jefferson Building and closes March 16.

The exhibition showcases more than 60 items dating from the seventh century to the present: Hebrew manuscripts, incunabula (pre-1501 books), a Torah scroll, the first Hebrew book published in the United States, a Yiddish-language version of the U.S. Constitution – and more than a dozen books donated by Schiff a century ago.

“We are pleased to be able to bring to the American people and visitors from around the world items from the collections of the Hebraic Section that have never before been exhibited, plus treasures that haven’t been on view at the Library in more than two decades,” said Peggy Pearlstein, head of the Hebraic Section.

Medieval rabbis and poets used the image of sapphires to convey the clarity of carefully selected words and the beauty of the written page – an idea that provided the exhibition with its title and inspired the presentation of the objects.

“Every exhibition at the Library is unique, based first on its content but also on its unique design,” said Kim Curry, a senior exhibition director in the Interpretive Programs Office. “For ‘Words Like Sapphires,’ we were inspired by the beauty of the objects in the exhibition, while the exhibit’s title inspired us to create a sumptuous, jewel-like presentation. We also worked closely with our designer to create a wide-open design because we expect the exhibition to be very well attended.”

The collection of Hebraica at the Library got its start in the early 1900s as part of an effort by then-Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam to build an institution that more fully represented the breadth of world knowledge and cultures.

“This was part of his overall vision of having a much broader library,” Pearlstein said.

Washington Haggadah (1478)

In this, Putnam sought the help of Jacob Henry Schiff, one of the most influential bankers and philanthropists of the age.

As head of the Kuhn, Loeb and Co. investment bank, Schiff helped finance America’s growing railroads, emerging companies such as Westinghouse and Western Union, and even Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05.

Schiff made a lot of money – he was worth an estimated $50,000,000 upon his death in 1920 – and donated large portions of it to charitable causes.

“Mr. Schiff spends almost as much time giving away money as in making it,” Forbes magazine reported at the time.

Schiff felt strongly about his Jewish heritage and devoted much of his life and fortune to supporting Jewish causes and institutions. His philanthropy helped support Hebrew Union College, the Jewish Theological Seminary and the Jewish Division of the New York Public Library.

To Putnam, Schiff seemed a natural choice to help establish a Hebraic collection at the Library of Congress. He also knew exactly what kind of help he wanted Schiff to provide.

In a letter to Schiff written on April 1, 1912, Putnam described a Hebraic collection owned by bookseller Ephraim Deinard and gently proposed that Schiff buy the material and offer it as a gift to the Library of Congress.

“I venture to lay this suggestion before you,” Putnam wrote.

Schiff obliged.

He purchased 10,000 books and pamphlets from Deinard – a collection that spanned nearly 500 years – and donated them to the Library. He also went Putnam one better: Schiff provided funds to hire a person specially designated to maintain the collection.

Schiff’s original gift and another donation in 1914 formed the basis of a collection that now includes more than 200,000 items in Hebrew, Yiddish, Ladino, Judeo-Persian, Judeo-Arabic, Aramaic, Syriac and Amharic.

“Washington wasn’t a large city at the time. It was small, and there wasn’t a large Jewish community,” Pearlstein said. “But scholars in the United States would be able to come here and do research. It put us on a par with the great national libraries of Europe.”

The exhibition, part of the Library’s multiyear “Celebration of the Book,” was made possible with support from the Abby and Emily Rapoport and the Naomi and Nehemiah Cohen trust funds at the Library of Congress.

Several other programs are planned in conjunction with the exhibition.

Earlier this year, the Library published “Perspectives on the Hebraic Book: The Myron M. Weinstein Memorial Lectures at the Library of Congress.” The book will be the subject of a free, public program at the Library on Oct. 29.

On Oct. 25, Emile Schrijver, curator of the Jewish special collection at the University of Amsterdam, will discuss “The Jewish Book Since the Invention of Printing.” On Nov. 5, poet Peter Cole will discuss “One Hundred Years of Hebrew Poetry.”

“It’s an exciting moment to be able to celebrate a centennial, and we’re looking forward to the next century of collecting material and making it available to researchers and the public,” Pearlstein said. “It’s not an end. It’s really just a stop along the way for what I hope will continue to be more wonderful materials we can acquire for the Library.”

October 24, 2012

Dear Diary

LeRoy Gresham (1847-1865) was a teenaged invalid who kept a diary for nearly every day of the Civil War, recording the news, his Confederate sympathies and perceptive details about life on the homefront as he experienced the conflict through newspapers, letters and personal visitors. The son of an attorney, judge, and plantation owner in Macon, Ga., Gresham’s diaries provide a poignant record of his suffering and that of his family during those trying times.

LeRoy Wiley Gresham, diary entry of November 17, 1864. Lewis H. Machen Family Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

Gresham had just turned 17 when Gen. William T. Sherman’s Union forces left Atlanta for the army’s “March to the Sea,” November-December 1864. Macon was thought to be in the line of advance, and LeRoy Gresham’s diary reflects the uncertainties felt by many Georgians who feared their homes would be in Sherman’s path.

An entry chronicling the historic event, dated Nov. 17, 1864, will be featured in the Library’s “The Civil War in America” exhibition, opening Nov. 12. The diary has never before been on public view.

“Clear and warmer. Rode down to Dr. Emerson’s and found the town in an uproar about the approach of the enemy, who are this side of Griffin and ‘marching on,’ 10 & some declare 15,000 strong. The trains have been running in all day with the stores, etc. The College will be broken up tis thought. We have about 10 or 11,000 to oppose them & I can’t see why Macon should give up. 8 P.M. We have received the following from Mr. Bowdre which I copy for future reading:

‘Mrs. Gresham: The news is bad enough: our forces have been compelled to retreat, & were at Barnesville last night (40 miles from Macon) & Gen. Toombs tells me they will be some 15 miles from Macon tonight—I mean ours— Sherman’s army is coming on as rapidly as they can; his cavalry camped last night, it is said, only 10 miles from Forsythe in Butts co. He is coming in two columns—it is thought by those who ought to know that Sherman’s forces will be here on Sunday or Monday, possibly sooner, unless opposed & we have too small a number to do anything much I fear. We may fight him in this vacinity [sic] but I fear not with any chance of success. Gen. Toombs advises all ladies & children to get away if they can. He is now at our store. I am greatly disturbed myself about my family. Yours in haste P.E. Bowdre.’

“We do not know what to do or think. We have no place to run to, where we could be safe, and we feel awfully about it. The town is in a furor of excitement & I fear little or nothing will be done to save the town. If Father were only here!”

Gresham began a final diary entry on June 9, 1865, and died nine days later due to causes unknown.

His “voice” will also be lent to a special blog featuring historical Civil War figures and complementing the upcoming exhibition. You can read more about it here.

Stay tuned next Wednesday for another spotlight on other items from “The Civil War in America.” Until then, you can read about them in these previous blog posts:

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers