Library of Congress's Blog, page 43

June 24, 2021

Pride Night Online! Coming June 28

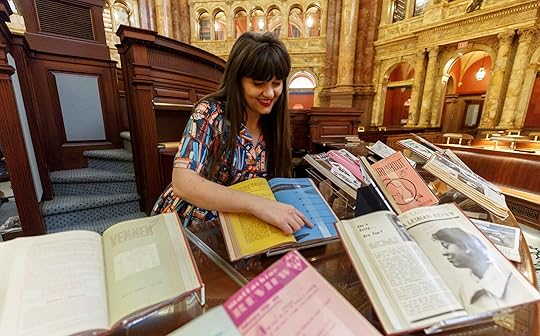

Megan Metcalf with some of the Library’s LGBTQ collections. 2019. Photo: Shawn Miller.

This is a guest post by Megan Metcalf, the Women’s Gender and LGBTQIA+ studies librarian and collection specialist.

The Library is celebrating LGBTQ+ Pride month with a slate of programs to help readers understand and find LGBTQIA+ collections from across the Library. (LGBTQIA+ is an acronym used in the Library’s collection policy statement to signify lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and asexual.) One of the key resources for you to explore our collections is our Research Guide on the subject.

To get a great understanding of that and other resources, join us for Pride Night Online, June 28 at 6 p.m. I will explore the breadth and diversity of LGBTQIA+ collections and services at the Library. I’ll provide a brief overview of what’s available in each reading room and research center and offer a detailed introduction into the rare and unique holdings in the Library’s general and international collections.

Finding trans and gender nonconforming histories through historical newspapers from Chronicling America.

Using local history and genealogical resources to trace LGBTQIA+ people.

Exploring the first LGBTQIA+ magazines published in the U.S., including the Mattachine Review (1955–66), ONE Magazine (1953–69) and The Ladder (1956–72).

Locating historical resources on LGBTQIA+ activism and organizing.

Understanding LGBTQIA+ digital collections, including the LGBTQIA+ studies web archive.

Learning LGBTQIA+ research tips and tricks, including how to find and request materials.

The event is free, but we suggest you register beforehand.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

June 21, 2021

The Great Buchanan Inheritance Hoax

President James Buchanan’s name was used to lend credibility to the hoax. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Candice Buchanan, a reference librarian in the local history and genealogy section of the Main Reading Room. Her most recent piece was a guide to finding female suffragists in family histories.

Ninety years ago, as the Great Depression drained hopes and finances across the country, a Texas grocer named Lorenzo D. Buchanan stepped forward with one of the great hoaxes of 20th-century American pop-culture life, a genealogical fabrication that continues to resonate today.

Lorenzo, who ran a modest store in Houston, told reporters a whopper: The $850 million estate of one of his ancestors was ready to be distributed among eligible heirs who could prove kinship.

This ancestor, he said, was William Buchanan, who had left the bequest tied up in recently expired, 99-year land leases across the country, which included prime Manhattan real estate. William was said to be a cousin of former President James Buchanan, which lent the story credibility.

Genealogical pandemonium ensued.

Americans went bananas. Everyone named Buchanan, or related to someone named Buchanan, or who thought they might possibly have a distant cousin twice removed was suddenly researching Buchanan history. Others just made up connections and hoped nobody noticed.

It went on for five incredible years, even after Lorenzo and his lawyer said the story was completely fabricated, even after judges and economists said the estate didn’t exist, even after genealogical experts at the Library said there were no family ties to claim. Then it resurfaced from generation to generation, as the aging children of parents who had been taken in by the scam came across old paperwork in attics, family Bibles, scrapbooks that showed…they could inherit millions!

I know this because my family was caught up in the hysteria, too.

I came across my family’s claim as a teen in my small Pennsylvania town. It didn’t come with a warning label. There was just paperwork, waiting to be notarized, that showed we were eligible heirs. It was incorrect and had been assembled by an apparently unscrupulous agent, but it certainly looked official.

That happened all over the U.S. when the hoax was at its height and people were desperate for any sort of financial hope.

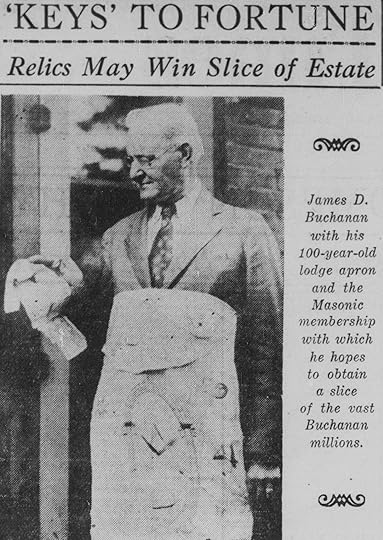

James Buchanan of Indianapolis thought he was heir to the multi-million dollar estate. Indianapolis Times, June 2, 1931. Chronicling America.

Newspapers across the country were filled with sensational stories about a local family who was anticipating their enormous inheritance any day now.

The Library was inundated with Buchanan genealogical requests. Overwhelmed librarians prepared a standardized memorandum, in which they explained that the most reliable records in our collections did not support a relationship to the fabled William Buchanan. Nor could they be sure that such a person had even existed.

At the same time, New York state surrogate judges, who presided over wills and estates, faced an onslaught of inquiries from people insisting to see a probate file of which the court had no record. The judges implored the state’s governor (and soon-to-be presidential candidate), Franklin D. Roosevelt, to intervene.

It should have ended then. Lorenzo, who had grown weary of the hoax, said that he had “ceased all operations in connection with the supposed estate.” Newspaper articles show that he even signed an agreement with the U.S. Postal Inspector to return — unopened — the thousands of letters people were sending him.

And yet, the hoax just gained steam. Mysterious “agents” suddenly appeared, saying they could help aspiring heirs file claims. In New York state, fees ranged from $15 to $250 — about $280 to $4,700 in 2021 dollars.

The issue came to a final showdown in a civil suit against Lorenzo Buchanan in 1936. It was thrown out of court, with his attorney mocking plaintiffs for having believed his client’s tall tale. Buchanan cited poor health, never appeared in court and never explained why he had concocted the hoax. He likely made some money off the episode, but it wasn’t the type of scam, or Ponzi scheme, from which he would have pocketed much.

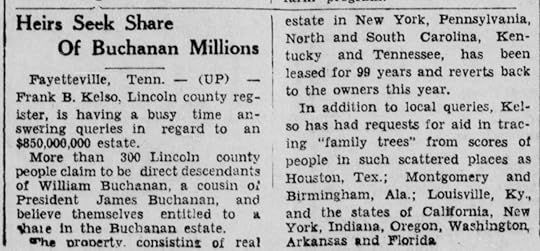

More than 300 people in Lincoln County, Tennessee, claimed to be descendants of the fictional William Buchanan. The Frontier, Holt County, Nebraska. August 20, 1931. Chronicling America.

Why had so many people believed in something that was so easily proven false?

Part of it is natural, as any genealogist can tell you. There is an inherent curiosity that can make us wonder if we are related to people who share our name. No scam is required to draw potential descendants towards branches of the family tree that ascend to celebrity ancestors such as heroes, leaders, founding fathers or nobility. The problem with many of these trees is that they are intended to connect living generations to a particular ancestor rather than to an accurate ancestor.

The Buchanan estate not only combined name recognition with celebrity, it also offered a mirage of financial relief during a period of extreme economic hardship. Buchanan family trees, many of them false, began to grow toward the former president. Since he was a bachelor with no known children, Buchanans attached themselves to the President’s siblings or to his father’s siblings, allowing more room for false hopes and fabricated claims.

“The Buchanan Book,” published in 1911, includes a small section devoted to the lines of American Buchanans. During the hoax, people used the book as a guide, but often mistakenly (or fraudulently) inserted one of the included names into their own family tree as a distant relation of the former president. Presto! You had a legitimate-looking family tree that showed you could inherit millions. That was the type of document I came across in my family’s papers so long ago.

I was hardly alone in coming across these kinds of claims. In the 1960s, three decades after the hoax was exposed, Library records show congressmen were still asking the Library for help in tracking down Buchanan claims sent in by constituents.

Today, genealogists are unlikely to believe they can still inherit from the alleged 1930s estate, but they do get misled by the fake family trees handed down to them. It’s easy to see why.

Family heirship claims leave behind documents that have the appearance of authenticity. They may be notarized, published, or written in a beloved grandmother’s hand. Then these family papers are inherited by unsuspecting descendants.

One of the reasons these genealogy mistakes are hard to correct is because genealogy is so personal. It’s not just history, it’s our history. We bond to it, especially if it’s a story that has been shared in our families. If we’ve been told that we have a famous ancestor or we come from a certain part of the world, those things get ingrained in our identity. It’s very hard to help people change their minds because it’s not just in their minds, it’s in their hearts.

Fortunately, genealogists can overcome these obstacles by doing their own research. Climb the family tree by beginning with yourself and working backwards one generation at a time. Collect and evaluate records, interview relatives and address conflicts. Be mindful of facts that don’t fit – and be wary of any claims to fame or fortune!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

June 18, 2021

The Birth of Juneteenth Wasn’t Big News in 1865

Betty Bormer, who was freed by the military order that founded Juneteenth. Fort Worth, Texas. June 26, 1937. Photo: Works Progress Administration. Prints and Photographs Division.

Journalism is often called the first draft of history. As any writer can tell you, first drafts are often messy.

So on this momentous day, the first federal holiday of Juneteenth, let’s look at how 19th-century media covered the birth of what would become the nation’s official holiday marking the end of slavery. That was the June 19, 1865, order by Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger in Galveston, Texas, that abolished slavery in that state, the last Confederate holdout.

Granger did not bury the lead. He established the legal authority to assume military command in the state and named his staff in two brief general orders, or military proclamations. Then he cut to the heart of the matter in “General Orders, No. 3.”

“The people are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves.”

Clear and concise. Not a word wasted. Black people in Texas, the last in America to find out that the Emancipation Proclamation applied to them, were out of bondage. Slavery was dead. A terrible era was over.

Today, we mark that announcement as a very big deal. The nation, founded on the ideal of equality, fought the deadliest war in its history over slavery, yet waited 156 years to officially mark the demise of the institution. There’s a lot to unpack in that, and we, as a nation, continue to do so.

But how did newspapers report it at the time?

By and large, they didn’t. Or just barely.

Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger. Photo: Brady’s National Photographic Portrait Galleries. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Galveston Tri-Weekly News, the Galveston News and the Houston Telegraph all reported Granger’s orders on June 20. These notices would, in the coming weeks, be picked up by other newspapers across the country. “The Slaves Declared Free,” ran a small front-page headline in the New-York Daily Tribune on July 7, prioritizing that declaration above the other four that Granger issued that day.

But by and large, most newspapers that can be found in the Library’s Chronicling America archives and in other databases available on-site show that most newspapers paid scant attention. The slavery order, if mentioned at all, was often just a one-sentence notice, deep in the sea of tiny type that characterized newspapers of the era, a pointillist’s dot in a newspaper mural.

Surprisingly, the only major dispatch from Galveston that week, which focused on the mood of the city, didn’t mention the orders.

“Jatros,” a correspondent for the New-York Daily Tribune, on June 20 filed a first-person account of walking through Galveston. He seemed unaware the order had been issued the previous day. “Galveston is a city of dogs and desolation,” Jatros wrote, in a colorful piece that would take two weeks to be printed in his own paper, then be republished by several others. He noted that “colored” Union troops kept the peace, but still referred to the local black population as “slaves.”

William Moore, who was freed by the military order that founded Juneteenth. Dallas, Texas. Dec. 21, 1937. Photo: Works Progress Administration. Prints and Photographs Division.

Jatros noted that livestock roamed the streets at will, that the city’s low-slung houses were often painted yellow, that the stores were dingy and devoid of merchandise, that the people were “stunted and scraggy” like the local trees. It was, by far and away, the most in-depth report from the place where Juneteenth originated, and yet it did not note that Black people were now free.

On Saturday, July 1, the weekly Dallas Herald printed all of Gordon’s orders but buried the item on the paper’s second page, along with noting that there had been a fine rain recently. On July 8, the Cincinnati Daily Inquirer reported the “all slaves are free” passage in a news round-up under the headline of “Afternoon Telegraph From the South-West.”

While all this might today seem a historical omission, that wasn’t necessarily true at the time.

Almost everyone outside of Texas already knew that slavery was over. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, freeing enslaved people in the secessionist states, had gone into effect on January 1, 1863. The Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery, had passed the U.S. Congress in January, 1865, and was being ratified by the states. Robert E. Lee, the Confederate military leader, had surrendered his army at Appomattox, Virginia, on April 9, 1865.

By June, Lincoln had been assassinated and the trial for his killers was underway. Debate raged about the fate of former Confederate troops and politicians. The new president, Andrew Johnson, was in the midst of appointing provisional governors to take control of the rebellious states.

In this turbulent, pell-mell of violence and the after-shocks of four years of war, the fact that a little-known military officer read a proclamation reiterating that slavery was indeed over in one far-flung state was not exactly earth-shaking.

“While it is difficult to know precisely why Gen. Granger’s General Orders No. 3 did not receive more press coverage, it coincided with a time when other national news likely took precedence for newspaper editors,” says Michelle Krowl, the Library’s Civil War and Reconstruction specialist.

Besides, whites in Texas did not exactly regard Granger’s orders as good news, as a New York Times piece on July 16 made clear. The paper reported that nine days after Granger’s orders were issued, the mayor of Galveston called a meeting of the city council to address the “altered condition of the colored population, which required new regulations for the protection of the citizens.”

Granger took quick action. The next day, he decreed that “No persons formerly slaves will be permitted to travel on the public thoroughfares without passes or permits from their employers, or to congregate in buildings or in camps at or adjacent to any military post or town.”

In less than 10 days after obtaining “absolute equality,” Black Texans were ordered – by the federal government, their supposed liberators – to get permission from their former owners to so much as walk down the street. It was a harbinger of the false promises of Reconstruction.

Still, for the one group of people who did regard Granger’s order as a revelation — Black Texans — the news was earth-shaking. They staged celebrations on the first anniversary of Granger’s order and, by 1872, a group had pooled resources to buy what is now known as Emancipation Park in Houston for their observation of what became known as Juneteenth.

It seems plain that is the spirt which today, a century and a half later, marks this as a federal holiday. Juneteenth is not a holiday simply because of Granger’s order. It exists because black Texans celebrated it for years, decades, more than a century, in the teeth of Jim Crow segregation and racist violence, in the unyielding belief that the United States might someday become a land of the free.

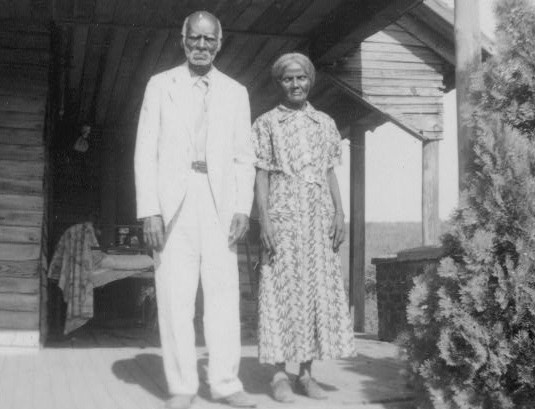

Anderson and Minerva Edwards, who were freed by the military order that founded Juneteenth. Marshall, Texas, Aug. 3, 1937. Photo: Works Progress Administration. Prints and Photographs Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

June 16, 2021

Free to Use and Reuse: The Photographs of Bernard Gotfryd

CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite reporting on the 1980 presidential election. Photo: Bernard Gotfryd. Prints and Photographs Division.

The photographs of Bernard Gotfryd, now free for anyone to use from the Library’s collections, are a remarkable resource of late 20th-century American pop-culture and political life, as he was a Newsweek staff photographer based in New York for three decades.

In his work, you’ll find film stars such as Dustin Hoffman on the set of “Midnight Cowboy,” novelists, painters, singers and songwriters, politicians at podiums and any number of passionate people at street protests. Gotfryd, who died in 2016 at the age of 92, left the bulk of his photographs to the Library and designated that his copyright should expire at his death.

Gotfryd was a Holocaust survivor. The Germans overran his Polish hometown of Radom days after World War II started. Late in life, he wrote and spoke eloquently about the horrors of those years, touching thousands of listeners and readers. His 1990 book of autobiographical sketches, “Anton the Dove Fancier and Other Tales of the Holocaust,” was written after Newsweek assigned him to photograph fellow Holocaust survivors at a White House ceremony, then sent him back to Poland for the first time since the war to cover a trip by Pope John Paul II, a fellow Pole, to their home country.

”It was a very emotional time, and the memories flooded my mind more than ever,” he told The New York Times in a 1990 article, ”And I remembered my mother, the day she was being deported to the death camp, begging me to stay alive so that one day I could tell the world what the Nazis were doing. When I returned from Poland, I knew that day had come.”

Both his parents and grandmother were killed by the Nazis, as were the vast majority of the 33,000 Jews in Radom. Gotfryd worked as a teenage photo-lab apprentice in the Radom Ghetto for four terrifying years. People were shot, hanged, tortured, dragged off to death camps. He saw pictures of all these, as Nazi officers brought pictures of atrocities to his lab to be developed. He leaked copies of those to Alexandra, a young woman in the Polish Resistance, where they were widely circulated. She was killed in the Warsaw Uprising; he was caught and sent to Majdanek, a forced-labor and concentration camp, and then to a succession of five others before being liberated by American troops in May 1945.

“People entered the showers, but never came back,” he told students at St. John’s University in 2007. “I imagined that this is what hell looked liked.”

He was just 21 when he immigrated to the United States, joined the Army as a combat photographer, and eventually settled in the New York borough of Queens. He married Gina, a fellow death-camp survivor whom he met in New York. They had children and he settled into a job at Newsweek.

After he left the magazine 30 years later, he wrote “Anton” and other books about the Holocaust. He published a collection of his photographs, “Intimate Eye: Portraits by Bernard Gotfryd,” in 2006.

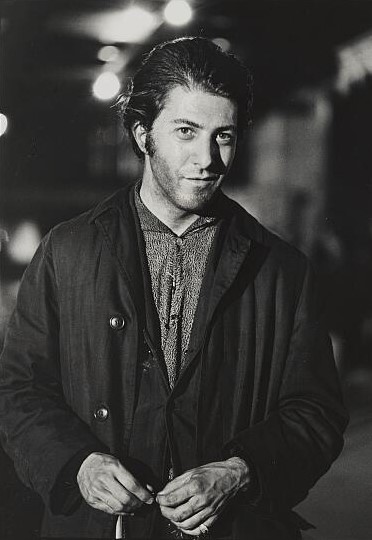

Dustin Hoffman on the set of “Midnight Cowboy.” 1968. Photo: Bernard Gotfryd. Prints and Photographs Division.

Much of his professional photography is now at the Library, with scans of 8,803 color slides now online. Due to his generosity, they may be used by anyone, free of all copyright restrictions. More than 11,000 of his black-and-white photographs are available through contact sheets and prints that can be viewed by visiting the Prints & Photographs Reading Room. (Other parts of his papers are held by the New-York Historical Society Library & Museum and the Hoover Institution.)

Gotfryd was a working photojournalist often limited by time and availability with his subjects, resulting in a clear and straightforward style, devoid of pretense, almost always using natural light. One can see the practicality of how he learned his craft. This captures his famous subjects without the artifice of elaborate photo shoots. They look like regular people.

His photograph of Walter Cronkite on the set of CBS News reporting the 1980 election (above), is an excellent matching of photographer and subject – both men practiced their craft in an unadorned manner that belied the technique behind it. There’s the U.S. map looming behind Cronkite, framing the national story against the smaller man narrating it. Today, it’s a postcard from another time; an era when people trusted network television anchors, when cable television was still just a novelty, when the internet and cell phones did not exist. There was Walter Cronkite telling you that was the way it was on this particular day and that was it.

Night falls on Manhattan. Photo: Bernard Gotfryd, 1983. Prints and Photographs Division.

Another image to which time has lent a pathos – his lovely twilight photograph of the Gotham skyline, the Twin Towers serene and majestic in the dusk, the shadows already deep across the canyons of downtown.

But I think my favorite of the lot is a simple picture of children he took on that decisive trip to Poland. It was June 1983, nearly four decades since he’d left the horrors of that place, and we know from the books that followed how deeply this trip affected him. Most of the pictures are journalistic images of the pope, the huge processions that greeted him and so on.

Polish kids waiting for Pope John Paul II in Katowice, Poland, 1983. Photo: Bernard Gotfryd. Prints and Photographs Division.

But here, he stops and turns his camera to the side. These are five girls, in traditional dress, perhaps for part of one parade or another, waiting along with two adults (chaperones?) for Pope John Paul II. Four are chatting and giggling. One is yawning. You can feel the sense of belonging, of nostalgia, that makes a man of nearly 60 turn his camera this way and see the humor, the fondness in it.

Still, it could not have felt like his place in the world any longer. There were about three million Jews in Poland before World War II; about 85 percent were killed during the Holocaust. Survivors were subject to occasional pogroms, causing more to flee. After a nationwide anti-Semitic government crackdown in 1968, some 13,000 Jews left the country in the next few years, roughly half of the nation’s already decimated Jewish population.

By the time of Gotfryd’s visit, there were only about 10,000 Jews in the nation. How it must have felt, this sense of alienation amid the nostalgia of home. It’s the kind of thing he wrote about until the end of his life, and captured in this deceptively simple image.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

June 14, 2021

Reading Rooms Reopen!

Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden greets researcher Jay Driskell following the opening of the reading room. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Reading rooms around the Library are reopening to researchers for the first time in more than 14 months, including four this week, as the Library begins to emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Performing Arts, Recorded Sound, Prints and Photographs and Moving Image reading rooms are opening this week, joining other rooms that opened on June 1. It’s not quite yet business as usual — appointments are required, and sessions are from 9:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. and 1 to 4 p.m. — but researchers were in the building as soon as doors opened.

They came in the dozens — both familiar faces and newcomers — to engage with an assortment of collections. One photographed Sanborn fire insurance maps; another examined Colonial-era legal documents; and yet another scrolled through microfilmed newspaper issues for stories documenting historical U.S. railroads. Library staff members were delighted.

“I missed being with the collections and excitement of the reading room,” said Lara Szypszak, a Manuscript Division reference librarian, whose division opened June 1. “There’s something about it that is impossible to replicate in the virtual world.”

The reading rooms of the Law Library, the Geography and Map, and Serial and Government Publications divisions also opened at the start of the month. The reopening is the first step in the Library’s plan to gradually resume on-site public services as the COVID-19 pandemic diminishes. Reading rooms, along with all other Library facilities, closed to the public on March 12, 2020, to reduce the spread of the COVID-19.

To visit one of the four newly opened reading rooms, researchers have to complete a reference interview and make an appointment at least 24 hours in advance, either by telephone or through Ask-a-Librarian. Two appointment times are offered: 9:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. or 1 to 4 p.m. During these times, only a limited number of researchers can be present to allow for social distancing. The Library has also installed plexiglass shields to protect staff and researchers from infection, and everyone in reading rooms must wear masks and follow the Library’s health and safety protocols.

None of these measures dampened enthusiasm among researchers. “We had people calling and writing in droves in the two weeks leading up to reopening,” Szypszak said. On June 1, 30 researchers visited the four reopened reading rooms. By the end of the first week, 97 had.

Historian and author Jay Driskell took a 9:30 a.m. appointment on June 1. He is the chief consulting historian for the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project at Northeastern University, and he came to consult the NAACP papers in the Manuscript Reading Room. He has used the papers extensively in the past to locate and document more than 1,000 cases of racial homicide in the South between 1930 and 1970.

Driskell first visited the Library about a decade ago to research his book, “Schooling Jim Crow: The Fight for Atlanta’s Booker T. Washington High School and the Roots of Black Protest Politics.” Since then, he has used multiple collections, both for his own research and writing and for his clients.

During the pandemic, he put the archival portion of his research on hold, although he continued to use the Library’s collections online for clients. The Prints and Photographs Division online collections “proved invaluable” for this purpose, he said, although “there’s only so much you can do with electronic sources.”

He explained: “There’s … something about the materiality of documents, about holding [them] in your hands that tells you something about the past you can’t get from an online database.”

Of the experience of returning to the Manuscript Reading Room, he said, “It really was fantastic to see everyone. … Even though I don’t work for the Library, I still view everyone here as my co-workers.”

Johanna Bockman, a sociologist at George Mason University, was equally effusive. “I’m a biased person” when it comes to the Library, she said, noting that she publishes a blog titled “The Library of Congress Is Great.”

She visited the Newspaper and Current Periodical Reading Room on June 1 to research microfilmed issues of the historical Washington Afro-American newspaper for a book she is writing about gentrification of Washington, D.C. “It’s wonderful” to be back, she said. “People are so helpful.”

Writer John O’Conor was in Newspaper and Current Periodical Reading Room the same day. He came to consult microfilmed newspapers published in New York, Philadelphia and Chicago between the 1880s and early 1900s for information about railroads. He’s been visiting the Library for 20 years and, like the others, was glad to return. “People remember me, I remember them,” he said.

For some researchers last week, it was their first visit. Benjamin Haller, a classics professor at Virginia Wesleyan University, is writing about the influence of Homer’s “The Odyssey” on Ralph Ellison’s work, and he came to the Manuscript Division to view the manuscript of Ellison’s “Invisible Man” and the author’s correspondence with scholars.

“It’s a huge honor to be able to come,” Haller said. “This is my initiation.”

Bruce Linskens is an analyst for the law firm Baker McKenzie. He visited the Law Library’s reading room to look at British Colonial appeal papers for an international case he is working on. He found both the manuscripts and librarian Nathan Dorn, “who pulled documents out beyond our initial request,” very helpful. “I hope I have another project that I can come back,” Linskens said.

Reference librarians had a similarly upbeat attitude about the reopening. “It went very smoothly,” Julie Stoner, a reference librarian in the Geography and Map Division. “Our patrons were happy to be back, and there was a feeling of celebration … as well as a sense of finally returning to normal.”

Librarian Gary Johnson said Newspaper and Current Periodical Reading Room staff tried provide the best service possible to patrons while the reading room was closed — he has been coming to the Library twice a week since July 2020 to respond to reference inquiries that required use of on-site resources. “But there are certain types of work that researchers can only do for themselves, so it is really satisfying to see that work begin again,” Johnson said.

Elizabeth Osborne of the Law Library said she is likewise pleased to facilitate access to collections, adding that she “missed the serendipitous interactions with … researchers and colleagues, which only occur when we are all together in the same room.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

June 10, 2021

The Birth Certificate for “America”

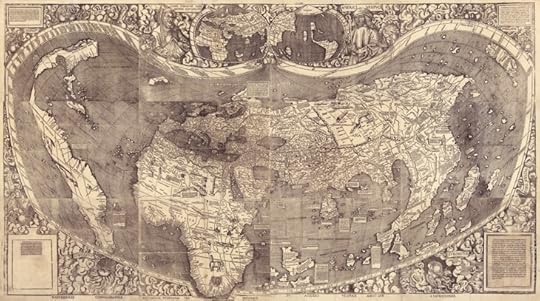

Martin Waldseemüller’s 1507 map used the term “America” for the first time in describing the New World.

–– This piece was co-written by Mike Klein, a reference specialist in the Geography and Map Division.

Few articles on the Library’s website in general, and this blog in particular, have stirred as much debate and discussion as a July 4, 2016, post titled, “”

The piece reports basic history: The name “America” originated with the famous 1507 map by Martin Waldseemüller, who named the newly-discovered lands for the sea-faring voyages of Amerigo Vespuccui a few years earlier. The German cartographer suggested the land be named “ab Americo Inventore…quasi Americi terram sive Americam,” translated as, “from Amerigo the discoverer…as if it were the land of Americus or America.”

With this map (the Library holds the sole surviving copy), Waldseemüller added the Western Hemisphere to the conception of the world, asserting the existence of a separate continent in the west, surrounded by water and lying apart from Asia. It was also the first time the word “America” had been applied to it. The map is one of many featured in the current issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, “Mapping our Place in the World.”

In “Cosmographiae introductio,” Waldseemuller wrote of his map: “Today these parts of the earth have been explored more extensively than a fourth part of the world, as will be explained in what follow, and that has been discovered by Amerigo Vespucci [. . . .] I can see no reason why anyone would object to calling this fourth part Amerige, the land of Amerigo, or America, after the man of great ability who discovered it.”

Obviously, the name “America” predates “the United States of America,” which was founded in 1776, and Waldseemüller was clearly referring to what we now call South America. But for five years now, that 2016 post has bounced around the internet’s chat rooms, taking on a life of its own, as readers from around the world have debated the origin of “America” and its modern usage as shorthand for the United States. It is so popular that is has racked up 100,000 more views than the second-most popular story on this blog.

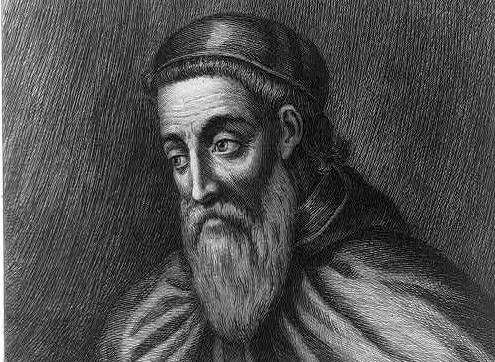

Amerigo Vespucci, 1902 etching by Jacques Reich. Prints and Photographs Division.

The map also portrays several of the Caribbean Islands and a small arch of land that we now recognize as North America. It shows the Pacific Ocean, although neither Magellan nor Balboa had yet reached it. As the Library’s interactive guide to the map notes, the cartographic sources that Waldseemüller used for his depiction of the New World remain a mystery, although he mentions some unknown Portuguese charts in “Cosmographie.”

The map was part of an era of world-shaking discoveries. Just 36 years later, Copernicus revolutionized our perception of Earth’s place in the universe, establishing that the sun, not the Earth, was the center of the solar system.

The revolutionary advances of Copernicus and Waldseemüller shifted the understanding of the Earth during the Renaissance, when European artists and scientists combined inspiration drawn from classical sources with information derived from Spanish and Portuguese voyages to put forth a more humanistic form of geography and self-awareness.

Waldseemüller knew the map would be shocking to many and seemed to anticipate the controversy that it would entail.

“This one request we have to make,” he wrote, “that those who are inexperienced and unacquainted with cosmography shall not condemn all this before they have learned that it will surely be clearer to them later on, when they have come to understand it.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

June 7, 2021

Grab the Mic: Jason Reynolds June Newsletter

You know what’s weird? Washing clothes. It’s like some kind of strange sorcery I can’t quite get a grip on. This isn’t to say I don’t do laundry. I do. Often. Doing it right now, as a matter of fact. Which is why I’m so fascinated by the whole experience. I mean, can you explain to me how putting dirty clothes in a machine, adding some soap and then pushing a button, which causes the internal chamber of this machine to fill with water and then just … move around for 20 minutes, cleans clothes? I mean, if I cover myself in soap, and get caught in the rain and then just jump up and down for a few minutes, will I come out cleaner? I don’t think so. So, how does the washing machine work? How? How?

You know what’s weird? Washing clothes. It’s like some kind of strange sorcery I can’t quite get a grip on. This isn’t to say I don’t do laundry. I do. Often. Doing it right now, as a matter of fact. Which is why I’m so fascinated by the whole experience. I mean, can you explain to me how putting dirty clothes in a machine, adding some soap and then pushing a button, which causes the internal chamber of this machine to fill with water and then just … move around for 20 minutes, cleans clothes? I mean, if I cover myself in soap, and get caught in the rain and then just jump up and down for a few minutes, will I come out cleaner? I don’t think so. So, how does the washing machine work? How? How?

The answer is, who knows? But I’ve been thinking about it anyway and wondering if life works that way, maybe not when it comes to cleaning our skin, but maybe when it comes to refreshing our minds and our hearts. Renewing our perspectives. What if we have been in some kind of strange washing machine for the last 15 months, filled with water, bumping us back and forth, rocking us, spinning us, jerking us around? And maybe the soap, the cleaning agent, has been, somehow, our teachers, our parents, our friends. Maybe we’ve been cleaning agents for other people, someone’s Tide Pod, which is also interesting to think about because the cleaning agent is in the storm of the machine just like the clothes. It has to be in it in order to help. It has to be able to understand the weight of the water and the unpredictability of the process. And after all the wishy-washy, and that violent spin at the end (which happens to be my favorite part … a Ferris wheel of FURY!), what if we’re made better? Fresher. What if there are things we’ve been able to finally release from our fibers. Stains we’ve finally been able to let go of?

I don’t know. It’s just something I’ve been thinking about as I put another load in. Something I’ll be thinking about all summer, as the world slowly reopens. Will life fit differently on us. Will we wear it with more pride, more confidence, more gratitude?

Something I’ve been thinking about. Or … I mean … maybe I just want to go swimming. Could also be that.

Have a good summer, everyone, and I’ll check in with you in fall!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

June 4, 2021

The White House Scientist and the Ancient Jewish Book

Vice President Kamala Harris swears in Eric Lander as Director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy. Lori Lander holds the 1492 Perkei Avot for her husband. (Official White House Photo by Cameron Smith)

Once upon a time – May 8, 1492, to be precise – a Jewish printer in Naples made the first printed text of the Mishnah, the collection of Jewish laws, ethics and traditions that had been kept orally for centuries. In the post-Gutenberg world of early printing, this was a rare and important part of Hebrew “incunabula,” as books printed before 1501 are known.

Centuries passed.

The New World was explored. Copernicus proved the Earth was not the center of the universe. Shakespeare came and went. Nations rose and fell. Plagues, wars and famines swept across continents.

And still, part of that 1492 Mishnah survived, in particular a 13-page fragment of the “Pirkei Avot,” or “Chapters of the Fathers,” a short, oft-quoted tract that sums up Jewish ethics and moral advice, often in easy-to-remember adages.

At some point, the fragment made its way across the Atlantic to the United States, bound in a bland Victorian-era-looking volume with a nondescript brown cover. It probably arrived in the Library in 1912, lost in a sea of about 10,000 volumes donated by Jacob H. Shiff, the railway magnate and Jewish philanthropist.

Another century passed.

And then this week, that 529-year-old book made a starring appearance under the hand of Eric Lander, a man who helped map the human genome, when he was sworn in by Vice President Kamala Harris as the director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. Lander, 64, who is Jewish, used the book as the sacred text upon which he swore his oath to uphold the values of a nation that was not even a notion when the book was printed.

“I just had this sense that books tell stories and the place to go was the Library of Congress,” Lander said, explaining how his search for a historic copy of the Mishnah led him to the Library’s Hebraic section.

Lander zeroed in on chapter 2, verse 16 of “Pirkei Avot,” which speaks to the value of Tikkun Olam, or the endless task of repairing the world: “It is not incumbent upon you to finish the task, but neither are you free to absolve yourself from it.”

That espouses, Lander says, his family’s deepest values.

“We are (all) part of a continuous chain of people who are devoted to repairing the world,” he said. “That’s what keeps the world, you know, livable and good. And we make it better in this way.”

It’s a nice story, but the book had survived half a millennium only to nearly be lost to the ages. Had it not been for Ann Brener, the specialist in the Hebraic Section, neither Lander nor anyone else would have known the book still existed. And here the story becomes one of how the work of libraries preserve world cultures, from lifetime to lifetime, from century to century.

Brener found the book a decade ago, while sorting through about 40,000 rabbinic texts in the Library’s collections, nearly all from the 19th and early 20th centuries. They were fine copies but not particularly striking. But as soon as she touched the paper of this copy, she knew this book was far older. It was rag paper — “strong, thick, a bit fibrous to the touch.” This was a gem.

It was a major find – there are only about 160 copies of Hebrew incunabula known to still exist; the Library has 37 of them.

In her entry describing the work, she listed these among the “crown jewels” of the Hebraic Section at the African and Middle Eastern Division. She wrote: “These Hebrew ‘cradle books’ or incunabula, as they are more generally known, offer a truly representative view of early Hebrew printing, with works ranging from rabbinical commentaries and responses to poetry, belles-lettres, and Arabic philosophy. They come from the presses of some of the best-known Hebrew printers of late fifteenth-century Europe and span the three major centers of Hebrew printing during the first crucial decades of its existence: Spain, Portugal, and Italy.”

The place and year of the book’s printing – Naples, Italy, in 1492 – carried even more cultural context. The kings of Naples and of Spain were cousins, each named Ferdinand. But while the Spanish king instituted the Spanish inquisition, driving Jews from the region, the king in Naples offered Jews refuge.

To Lander, this made the book as meaningful as the words printed on its pages.

“The book itself told the story of a world in which some places were tolerant and some places were intolerant. It spoke about refugees and in a whole new dimension that merely downloading a PDF with the words would not.”

Still, even though Brener had found, identified and described the book in a Library document called a finding aid, the book wasn’t listed in Library’s online catalog, meaning it was invisible to anyone who looked for it via a computer search. (The Library has so many millions of items that getting them all online is an ongoing, massive task.)

To get the book listed online required the efforts of David Reser, a metadata librarian. In 2019, Eugene Flanagan, Chief of the Library’s General and International Collections Directorate, directed Guadalupe Rojas, an intern from the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities program, to transfer information about these ancient Hebrew texts onto a searchable spreadsheet. From there, Reser was able to upload the basic record of the book into the Library’s online catalog, even though the book itself is not yet catalogued.

It was, Brener said, “incredible magic” to get a book that had been lost to world view for five centuries to suddenly being available to anyone who typed in a few words on a computer.

And so it was from this daisy chain of events that a Harvard and MIT biologist and geneticist was able to go online to the largest library in world history and find a 13-page book from another age that spoke directly to him. Lander was so moved that he invited Brener to the swearing-in ceremony, bringing the 1492 “Pirkei Avot” with her. Lander’s wife, Lori, held it for him to place his hand upon while Harris administered the oath. It was really quite a moment.

“Although I chose a Jewish text, because it is my tradition and deeply meaningful to me,” he said, “it is also quite universal.”

June 3, 2021

Mark Twain Tonight! (1860s Edition)

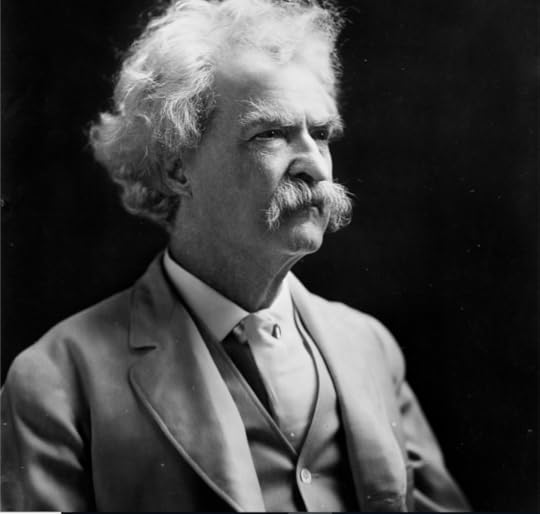

Mark Twain, 1907. Prints and Photographs Division.

Mark Dimunation, chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, wrote this piece on how the young Samuel Clemens perfected his wildly popular speaking tours.

A fledgling reporter in 1866, Mark Twain traveled to Hawaii, then called the Sandwich Islands, as a correspondent for the Sacramento Union. Over the five-month tour, he filed 25 vivid reports of his travels to various California newspapers and the stories captured an audience. Upon his return, he launched a speaking tour throughout California.

Initially, Twain was a hesitant and somewhat awkward presenter. His early take on the subject established his comical recounting of the values and the vices of the islanders. He closed his early programs with an apology for subjecting the audience to his talk, explaining that he needed the money. One early critic noted that his “method as a lecturer was distinctly unique and novel. His slow, deliberate drawl, the anxious and perturbed expression of his visage, the apparently painful effort with which he framed his sentences … All this was original, it was Mark Twain.”

That initial tour was so extraordinarily profitable that it established a new career for him.

Twain repackaged the lecture three years later for a tour of the Northeast. The talk was called, “Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands.” (As one would imagine, this is a talk infused with Twain’s comic sensibility as well as a decidedly 19th-century notion of social/political correctness. His comic lines are the ones that endure.)

He would eventually give this talk in various locales more than 100 times. “I shall tell the truth as nearly as I can,” he always liked to say, “and quite as nearly as any newspaperman can.”

A flyer advertising Twain’s speaking tour. He made up the insulting reviews, including the cannibalistic review from the Sandwich Islands. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

His cultural observations ranged from fairly serious tales of the islands’ volcanoes to a more relaxed view of the social life and customs of the residents. “They have some curious customs there; among others, if a man makes a bad joke they kill him. I can’t speak from experience on that point, because I never lectured there. I suppose if I had I should not be lecturing here.”

And a moment he used to great effect – his disavowal of the contemporary existence of cannibalism on the islands — “In other cities I usually illustrate cannibalism on the stage,” he admitted, “but being a stranger here I don’t feel at liberty to ask favors, but still, if anyone in the audience would lend me an infant, I will go on with the show.”

The talk was a huge success, so much so that in February 1873 he delivered his lecture on the Sandwich Islands at Steinway Hall for the benefit of the Mercantile Library Association. Steinway Hall was the same venue in which Twain heard Dicken’s American lectures while in New York as a special correspondent for the San Francisco Alta California newspaper in January 1868.

The New York Times reviewer noted that Twain “kept the audience convulsed with laughter…. His attitudes, gestures, and looks, even his very silence were provocative of mirth.” In this handbill announcing his New York lecture, Twain supplied the poster’s fictional editorial comments: “The most stupid lecture we ever heard;” “Twain is the homeliest man living;” “His lecture is a tissue of lies;” and, finally, a positive quote from the mythical Sandwich Islands Daily Express, offering up a cannibalistic appreciation of his performance!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

June 1, 2021

Now Online! Presidential Papers – Love and Heartbreak, War and Politics

Woodrow Wilson, a man in love. Prints and Photographs Division.

This story first appeared in the Library of Congress Magazine.

When President Woodrow Wilson’s name comes up, romance isn’t typically the first thing that comes to mind.

Yet, late on May 7, 1915, the recently widowed president penned these words to Edith Bolling Galt, days after confessing his love for her: “I know you can give me more, if you will but think only of your own heart and me, and shut the circumstances of the world out.”

That day, the circumstances of the world were weighing heavily on Wilson’s mind. Earlier, a German U-boat had torpedoed the British-owned luxury liner RMS Lusitania, killing 1,195 people, including 128 Americans. Wilson spent his afternoon and evening receiving updates about the horrific attack that threatened U.S. neutrality in a war that had already engulfed Europe and would eventually draw in the United States.

Researchers using Wilson’s papers at the Library may be surprised to encounter the private — and passionate — Wilson behind the formal and somewhat aloof public figure they recall from history books or World War I-era film footage.

“I must do everything I can for your happiness and mine,” Wilson continued. “I am pleading for my life.”

President Wilson, with his wife, Edith Bolling Galt. Photo: Harris & Ewing. Prints and Photographs Division.

Wilson’s plea apparently was persuasive: He and Galt, a wealthy Washington, D.C., widow, married before the year was out.

The Library’s collections of presidential papers hold some of the most important manuscript treasures in the nation, but they also shed light on the daily lives of the leaders and the inner circle of family, staff and confidants who helped mitigate the isolation every president feels.

Those collections are more accessible than ever before: All 23 sets of presidential papers held by the Library — a total of more than 3.3 million images — now are available and searchable online, an accomplishment more than two decades in the making.

“Arguably, no other body of material in the Manuscript Division is of greater significance for the study of American history than the presidential collections,” said Janice E. Ruth, the division’s chief. “They cover the entire sweep of American history from the nation’s founding through the first decade after World War I, including periods of prosperity and depression, war and peace, unity of purpose and political and civil strife.”

Those vast papers include documents fundamental to U.S. history: George Washington’s commission as commander in chief of the American army and his first inaugural address; Thomas Jefferson’s rough draft of the Declaration of Independence; the two earliest known copies of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address; the handwritten manuscript memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant; and Wilson’s shorthand draft of his famous 1918 Fourteen Points speech envisioning post-World War I peace.

They also reveal the personal side of these great figures.

There’s a small paperbound book recording Washington’s expenses in 1793–94 and receipts from Chester A. Arthur’s household (including for immense quantities of alcohol and cigars, likely purchased for entertaining). There are love letters from Grant to his wife Julia Dent Grant; James A. Garfield’s final diary entry, the day before his assassination in 1881; and details of the aftermath of the death of Maj. Archie Butt, an aide to Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft who died in the sinking of the Titanic in 1912.

A bereft Taft told mourners at a memorial service for Butt that, because a president’s circle is so circumscribed, “those appointed to live with him come much closer than anyone else.”

The Library’s collection of presidential papers begins with George Washington and ends with Calvin Coolidge. The National Archives and Records Administration, founded in 1934, administers a system of geographically dispersed presidential libraries that house and manage the records of presidents from Herbert Hoover onward.

The Library doesn’t hold the papers of all 29 presidents before Hoover. The papers of John Adams and John Quincy Adams, for example, are at the Massachusetts Historical Society, and the Ohio Historical Society holds those of Warren G. Harding. Rutherford B. Hayes’ family retained his papers and opened a library in 1916 at his home in Fremont, Ohio.

But the collections the Library possesses, acquired through donation and purchase, are of such high value that Congress enacted a law in 1957 directing the Library to arrange, index and microfilm the papers for distribution to libraries around the nation, an enormous job that concluded in 1976.

When it became possible to digitize collections in the mid-1990s, microfilm editions of presidential papers were among the first selected for scanning. Between 1998 and 2005, the papers of Washington, Jefferson, James Madison and Lincoln were digitized and put online: What once was available only on clunky microfilm machines became accessible to anyone with an internet connection.

Several years later, work resumed on digitizing the Library’s remaining presidential papers and, eventually, to migrate already-digitized collections to the Library’s updated web platform, which enables easier access, including on mobile devices. Some original documents were rescanned in high resolution at that time, and others — those not captured in the microfilm editions, along with documents subsequently acquired — were added.

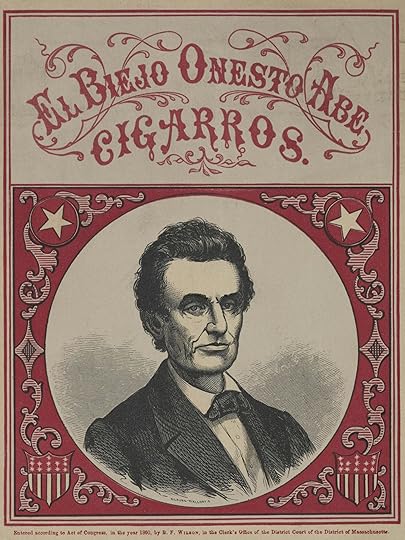

“Honest Abe” Lincoln cigar box label, spelled in phonetic Spanish, 1860. Manuscript Division.

In 2017, for example, the Library made a reading copy of Lincoln’s second inaugural address showing his editorial changes available on its website for the first time (it was not included in the microfilm edition), as well as a cigar-box label from his 1860 presidential campaign rendering his “Honest Old Abe” nickname in phonetic Spanish.

During just the past fiscal year alone, about 1.5 million new images were made available online, culminating in the release over the summer of the collections of Benjamin Harrison, Grover Cleveland, Coolidge and Taft.

Taft’s papers, consisting of 785,977 images, are the largest among the Library’s presidential papers, perhaps befitting a man who stood around 6 feet tall and weighed well north of 300 pounds. Wilson’s papers are the second biggest (622,211 images), followed by Theodore Roosevelt’s (462,638 images).

The mammoth feat of making all these collections available online involved many hours of labor by staffers and contractors at the Library.

Among the multitude of tasks performed, they scanned documents, provided necessary conservation treatments, performed quality review of images, set up server space, created digital files, indexed records and connected them to digital images, consulted on rights issues, wrote contextual frameworks for individual collections and created web presentations on the Library’s platforms.

“As they say, it takes a village,” Ruth said.

All the work was, however, well worth it.

“Like the original presidential papers and the microfilm copies, the online presidential papers are being used extensively by historians, educators and lifelong learners,” Ruth said.

Charles Calhoun is one such historian. Calhoun has used the Manuscript Division’s collections for 50 years and last year consulted the presidential papers of Garfield, Andrew Johnson, Harrison and Grant online.

The availability of these papers online, he said, is a godsend in an era of shrinking academic research budgets and dwindling travel funds — difficulties compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic and its attendant restrictions.

“The Library’s decision to offer these indispensable resources online represents a tremendous boon to scholarship,” Calhoun said. “It is a service that has rapidly become not merely conducive but vital to the advancement of historical scholarship.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers