Library of Congress's Blog, page 47

March 17, 2021

Women’s History Month: Latinas!

The is a guest post by Hispanic Division Huntington Fellows Maria Guadalupe Partida, Herman Luis Chavez, and reference librarian Maria Thurber.

Images used clockwise from top left – El Dia Internacional de la Mujer, by Deborah Dosamanes; Dia Internacional de la Mujer; Mis Madres, Easter Hernandez; We the people – defend dignity, by Shepard Fairey and Arlene Mejorado.

Last summer, as the global pandemic raged on and the need for digital resources continued, a group in the Hispanic Division decided to collaborate on projects highlighting the rich history and contributions of the Latina/o/x community. With support from supervisors, mentors, and colleagues, we — Huntington Fellows Lupita Partida and Herman Luis Chavez and Reference Librarian Dani Thurber — formed a group we call the Latinx Dream Team. Aided by video chats, calls, and text messages, we focused on all things Latina/o/x, from discussing the term “Latinx” to planning virtual events during National Hispanic Heritage Month. Despite working remotely from three different time zones and never having met in person, our combined efforts resulted in the publication of two new research guides: A Latinx Resource Guide: Civil Rights Cases and Events and Latinx Studies: Library of Congress Research Guide.

In celebration of Women’s History Month, we share the stories of Latina Luminarias whose lives, actions, and bravery inspired our work. We call these women Luminarias (luminaries) because they “lit the way” during challenging times. Luminarias, sometimes referred to as farolitos (“small lanterns”), are traditionally made out of paper bags with a small light source inside and weighted down by sand. A historical tradition from New Mexico, these little lights illuminate towns during winter’s darkness.

Jovita Idar’s El Progreso Park in Laredo, TX. Photo: Lupita Partida.

Jovita Idar

Journalist and community activist Jovita Idár was born in the border town of Laredo, Texas in 1885. Her parents founded “La Crónica,” a local Spanish-language newspaper that uncovered prevalent discrimination against Mexicans and Mexican Americans and roused activism among individuals residing in both Laredo and Nuevo Laredo. In 1911, Idár helped assemble the first Mexicanist Congress, a political convention that addressed socioeconomic discrepancies within Mexican and Mexican-American communities. Idár joined the journalists of “El Progreso” newspaper, where she criticized President Wilson’s military intervention at the U.S-Mexico border during the Mexican Revolution. After reading Idár’s political editorial, Texas Rangers arrived to shut down “El Progreso.” Idár firmly stood outside, prohibiting the Rangers from entering. Ultimately, Texas Rangers shut down “El Progreso,” but Idár remained an activist, writing pro-suffrage editorials for both “La Cronica” and “Evolución,” a newspaper founded by Idár alongside her brother.

Pura Belpré

Pura Belpré arrived in New York City in 1921 and discovered a need to connect the growing Hispanic communities across the city’s boroughs. As one of the first bilingual assistants hired by the New York Public Library, Belpré found fertile ground for bilingual cuentos folklóricos (folkloric stories) from her native Puerto Rico. Belpré wrote and published her own cuentos and went around the city telling stories and inspiring literacy. Belpré’s legacy lives on through ALA’s Pura Belpré Award, which honors her as one of the most influential librarians to promote children’s literature and for her service to the Latina/o/x community. In the Hispanic Division, we honor Belpré’s work by recommending diverse children’s and YA materials for the Library’s collections and hosting the annual Américas Award ceremony. Last year, Planting stories: the life of librarian and storyteller Pura Belpré received a commendation from the Américas Award committee.

Celia Cruz, 1962. Prints and Photographs Division.

Celia Cruz

The music of Celia Cruz can lift spirits even on the gloomiest day. Cruz grew up in Havana, Cuba exposed to diverse music and musicians. Known worldwide as the “Queen of Salsa,” Cruz recorded more than 70 albums and received countless accolades. In 2005, Cruz was awarded posthumously the Congressional Gold Medal. In 2013, the Library added Cruz’s collaborative album with Johnny Pacheco, “Celia & Johnny” (1974) to the National Recording Registry. With her distinctive shout “¡Azucar!” (“Sugar!”) while singing, Cruz’s voice and her music’s uplifting rhythm are wonderful reminders that life is beautiful despite adversity.

Sylvia Rivera

Sylvia Rivera, born Ray Rivera Mendoza, was a Latina transgender activist and drag queen with Puerto Rican, Venezuelan, and Mexican roots. During the 1969 Stonewall Uprising, Sylvia demonstrated against the police raid of the Stonewall Inn. Following this event, a wave of political activism emerged within the LGBTQ community, leading Rivera to press for New York City’s first gay rights ordinance. In 1970, Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson (1945-1992) founded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), a NYC-based organization that supplied lodging for homeless transgendered and queer youth. The Sylvia Rivera Law Project (SLRP), a non-profit organization that provides free legal services for transgender and gender non-conforming individuals was founded in 2002 to honor Rivera’s life-long activism for queer and trans people of color.

Rachael Romero. Stop forced sterilization. 1977. Prints and Photographs Division.

Antonia Hernández (1948-)

Antonia Hernández, born in Torreón, Mexico in 1948, is an attorney, civil rights activist, and the current president and CEO of the California Community Foundation, a philanthropic nonprofit organization that supports marginalized communities in Los Angeles, California. Hernández defended the women of Madrigal v. Quilligan, a class action lawsuit filed by 10 Mexican-American women against the Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center for involuntary or forced sterilization. From 1985 to 2004, Hernández was the president and general counsel of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF), a nonprofit organization that advocates for the civil rights of the Latina/o/x community.

Photo: Fajardo-Anstine by Graham Morrison. Photo of Antonia Hernández used with permission.

Kali Fajardo-Anstine (1987-)

Kali Fajardo-Anstine is a novelist from Denver, Colorado with Indigenous, Latina, and Filipino roots and a 2020 winner of an American Book Award. Fajardo-Anstine is the author of “Sabrina and Corina: Stories,” finalist for the National Book Award, a novel that captures the lives of Indigenous Latina characters in the American West. Winner of multiple awards and widely translated, “Sabrina and Corina” promotes a narrative of identity, heritage, and feminine empowerment. Listen to Fajardo-Anstine’s inspiring presentation and Q&A session during last year’s virtual National Book Festival.

The Latinas highlighted here are only a few of the women who inspired us this year. Please tell us in the comments about the Luminarias who have encouraged, nurtured, or taught you!

March 15, 2021

Was My Female Ancestor a Suffragist?

Suffragists Katharine McCormick and Mrs. Charles Parker (first name not recorded). April 1913. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Candice Buchanan, a research librarian in the local history and genealogy section of the Main Reading Room.

Finally. After seven decades spent lecturing, debating, writing, parading, suffering, and all-out fighting for it, women had the right to vote. The 19th Amendment was ratified on August 18, 1920. History was made, although as a practical matter, these gains only applied to white women at the time. Still, the paradigm had shifted.

Did your ancestor take part? Was she for or against such decisive reform?

It can be challenging to discover records that give dimension to the women in our genealogy. Suffrage provides an opportunity.

The enormous suffrage movement produced national superstars whose names are forever connected to the cause. Those women earned their prominence because they rallied broad participation across the country.

The boots-on-the-ground suffragists were the women in your community and family tree. These women labored for reform in their states, counties, cities, churches, schools, social clubs and families. At every level, women had to convince a majority of male voters and legislators to endorse suffrage. Only men could cast the ballots that would grant the same right to women.

Not all women were suffragists. A strong anti-suffrage movement coexisted and counteracted the cause. Some women kept their opinion private. Others avoided the topic altogether. To find out where your relatives were on that spectrum, you can begin with some basic genealogical research.

The suffrage movement lasted from the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 to the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920. To get started, first identify the women in your family whose lifetimes intersect that era. They did not have to be members of an official pro- or anti-suffrage organization to take a side. Investigate the positions of their social clubs, religious affiliations, political parties, family members, and communities for insights into how they may have viewed suffrage.

Library of Congress Collections and Exhibits

Next, the Library is home to significant historical material related to the suffrage movement, including the special exhibit, “Shall Not Be Denied: Women Fight for the Vote.” The exhibit has a virtual counterpart to explore online, which includes original papers of suffragists and suffrage organizations, photographs, historical accounts and more. Browse digital collections such as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) Records and utilize resources identified in the 19th Amendment research guide to understand the national movement and provide historical context for the roles your ancestors played.

Suffrage Organization Archives

Each suffrage organization had philosophies and action plans. Knowing which one(s) your ancestors belonged to will help you to understand their perspectives.

The most well-known suffrage organizations were the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), which merged in 1890 to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). After the 19th Amendment passed in 1920, NAWSA merged with the National Council of Women Voters to form the League of Women Voters, which is still active.

Similarly, the National Federation of Afro-American Women and the National League of Colored Women merged in 1896 to become the National Association of Colored Women (NACW). In 1904, NACW became known as the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC). Their work to overcome the challenges women of color face in the fight for equal rights is ongoing.

As the movement evolved, these groups continued to merge, adapt, or split. A prominent example of the latter, occurred in1917, when Alice Paul broke away from NAWSA to form the National Woman’s Party.

Other groups, though not specifically created to fight for suffrage, supported the cause. These organizations, such as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, became important allies.

To find out if your ancestors were members, search for the records of each organization. Seek out state and local chapters from the communities where your ancestors lived. In addition to Library, ArchiveGrid is a useful tool to locate collections at over 1,000 institutions nationwide. Reach out to state or university archives, county historical societies and community libraries. Most archives do not have every-name indexes. You’ll want to find the most likely collections and study their contents for ancestors’ names. If you do not find actual membership rosters, look for alternatives such as meeting minutes, correspondence, newsletters, and programs that may identify ancestors or their neighborhoods.

Newspapers

Suffragist activities were often reported in local newspapers. Sometimes members were identified or quoted. For example, in November 1920, many articles were written about the first women at the polls on Election Day.

The Library provides free access to Chronicling America, a collection of historic newspapers. It’s important to find the newspapers local to your ancestors’ neighborhoods. If those hometown papers are not yet posted to Chronicling America, use the U.S. Newspaper Directory to see which repositories house the archives.

Poll Taxes and Voter Registrations

If her state required a poll tax, find out if she paid it. For some areas, poll taxes have been digitized or published, but in most cases you will need to contact the county tax office or courthouse to access the original records. Voter registrations are also generally maintained at the local level. For family history purposes, these documents may reveal additional facts like name changes, birthdays, occupations, residences and taxable property.

There are limitations to poll tax and voter registration records because, in spite of the 19th Amendment, not everyone was given an equal opportunity to participate. Women of color, like men of color, were forced to overcome intentional obstacles such as literacy tests and the poll tax itself. If your ancestor does not appear as a registered voter, you may want to dig deeper into the local history of their town, county, and state to determine what tactics may have inhibited their opportunity to register to vote.

Poll taxes and voter registrations indicate what your ancestor did with her new right. They do not tell you how she felt about it or whether or not she took an active role in the fight for it. Nevertheless, this historic moment in the lifetimes of our female ancestors should be documented for every woman in the family tree who was qualified to vote on Election Day, November 2, 1920. Whether or not she registered to vote, or tried to register to vote, in the first election for which she was constitutionally eligible, is a relevant part of her story and her place in history

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 10, 2021

New! Read Around the States

This is a guest post by Guy Lamolinara, head of the Center for the Book and the communications officer for Literary Initiatives.

America’s rich literary heritage is reflected in its states and territories.

Today we are launching a project called Read Around the States. It features videos with U.S. members of Congress who have chosen a special book for young people that is connected to their states – either through the book’s setting or author, or perhaps simply because it is a favorite of the member.

Each video also includes an interview with the book’s author, conducted by the Affiliate Center for the Book in the member’s state. The Center for the Book is a Library program whose mission is to promote books, reading libraries and literacy nationwide. The mission is achieved with the help of a network of 53 Affiliate centers – one in each state, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. These centers work with the Library on its National Book Festival and other literary programs and events.

Three members have already recorded, and their videos go online today:

French Hill, of Arkansas’ 2nd Congressional District, reads from Kate Jerome’s “Lucky to Live in Arkansas” (Arcadia Kids Publishing). Jerome is in conversation with Jennifer Chilcoat and Ruth Hyatt of the Library of Congress Arkansas Center for the Book.{mediaObjectId:'BAEDD126BB00D591E053CAE7938CD55D',playerSize:'mediumWide'}Bob Latta, of Ohio’s 5th Congressional District, reads from Douglas Brinkley’s “American Moonshot: John F. Kennedy and the Great Space Race” (HarperCollins). Don Boozer, head of the Ohio Center for the Book at Cleveland Public Library, interviews Brinkley, who grew up in the state.{mediaObjectId:'BAEDD122FDD5D58FE053CAE7938C1270',playerSize:'mediumWide'}In this recording, Rep. Chellie Pingree, of Maine’s 1st Congressional District, reads from “The Circus Ship” by Chris Van Dusen (Candlewick Press). Hayden Anderson, executive director of the Maine Humanities Council and home of the Library of Congress Maine Center for the Book, interviews Van Dusen.

{mediaObjectId:'BAEDD12A95EED593E053CAE7938CAA68',playerSize:'mediumWide'}New videos will become available as they are recorded. Even if you or your children aren’t from these states, the videos are still a great way to see and hear these members of Congress reading favorite books and talking about what inspired them to make their choices.

Why not read a book yourself or read one with your children that is connected to your home state? It is sure to make you proud of your own state’s literary heritage.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 8, 2021

Researcher Story: Michelle Farrell

Michelle Farrell. Photo courtesy of the author.

Michelle Farrell has been writing since she won a citywide contest in the fourth grade for an essay titled ”What America Means to Me .” Later, as a journalist in New Hampshire, her favorite stories were about what brings people and places together, a theme she pursues now as a freelance writer. Her latest story, researched at the Library, explores the experiences of W.W. Denslow, the original illustrator of “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz,” in Bermuda. Denslow bought an island there in the early 1900s using royalties from his works.

Tell us a little about your writing career.

Most of my career was spent at a newspaper in southern New Hampshire, just up the highway from where I grew up in central Massachusetts. An expat journey through London and Bermuda came next. Twenty years after that adventure began, I host my own web site, combining all my different worlds.

What drew you to W.W. Denslow?

I started my research after a friend told me that Bermuda sunsets had inspired the yellow brick road in “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.” The timing of that tale isn’t right — Denslow arrived in Bermuda after “Oz” — but I was intrigued just the same.

Later, I took a tour boat ride with some visitors. Our guide pointed out the white turreted house that Denslow lost in 1911 when his money ran out and the island fantasy ended. Off I went to find out more.

Farrell’s work at the Library. Photo: Michelle Farrell.

What collections did you use at the Library?

First, I read the score for “The Pearl and the Pumpkin” in the Performing Arts Room. The 1905 songbook is a record of Denslow’s musical extravaganza, a show inspired by his new island home. Denslow designed the scenes and costumes for what was supposed to be his next-big-thing — a spectacle to rival “Oz.”

In taking the time to read the old songbook firsthand, I had hoped to find a link — in lyrics, in tone, in color — to his beloved Bermuda.

Second, I requested a playbill from the Library’s Theater Playbills Collection from December 1905. This is when the musical played at the New National Theatre in Washington, D.C. The playbill’s detailed scene list hints at a Bermuda vibe, ending, “On the South Shore, midnight” — one of the loveliest nighttime settings I know. Perhaps the fairy-tale artist felt the same.

Third, I looked at the digital collection of “The Wizard of Oz: An American Fairy Tale,” a 2000 exhibit at the Library. For my research, two pieces in the collection stood out.

First, there was “Oz” author L. Frank Baum’s letter to his brother Harry in April 1900 anticipating the upcoming publication of “Oz” later that year. “Denslow has made profuse illustrations for it and it will glow with bright colors,” Baum wrote. Later, he would seek to downplay his illustrator’s contributions, according to research cited in my article.

Second, there was a copyright registration filed in the U.S. Copyright Office with both men’s names inked in. The two collaborators would later disagree on just what that copyright permitted. Baum, for example, felt Denslow had no right to use the “Oz” images in his later works.

What was your experience like at the Library?

As a first-time Library user, I was a bit in awe, but there was no need for me to be intimidated. Even a beginner is treated like a scholar.

Can you comment of the value of the Library’s collections to researchers?

Viewing the original documents for me was invaluable, although perhaps on more of an emotional versus scholarly level. I could have saved myself the trouble and viewed the score and the playbill online. But reading the pieces firsthand helped me to find some of that long-ago island wonder that captivated the “Oz” artist.

For example, there’s the musical piece “Lily White” near the end of the musical. It was inspired by the cultivated lilies in Bermuda and maybe the wild ones around Denslow’s island home with its sunset views. With a little imagination, I could picture those same flowers on the browned pages dancing on Broadway more than 100 years ago.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 4, 2021

Jason Reynolds: Grab the Mic, March Edition

My mother is 75. And that means a lot. It means she’s lived over 27,000 days, which is a whole bunch of days. It means she remembers when watching television was for fancy people—a luxury. Same as running water. And electricity. She remembers the civil rights movement, the March on Washington, the death of Dr. King and President Kennedy. She remembers America going to war and to the moon and to the disco. She remembers the first computer, the first beeper (ask your parents) and the first cellphone. And it’s this last one, the cell phone—well, really the “smart” phone—that’s stumped her. It’s the smart phone, its glowing touchscreen and cartoonish icons, that’s turned her 75 years into what feels to her like 75 minutes.

My mother is 75. And that means a lot. It means she’s lived over 27,000 days, which is a whole bunch of days. It means she remembers when watching television was for fancy people—a luxury. Same as running water. And electricity. She remembers the civil rights movement, the March on Washington, the death of Dr. King and President Kennedy. She remembers America going to war and to the moon and to the disco. She remembers the first computer, the first beeper (ask your parents) and the first cellphone. And it’s this last one, the cell phone—well, really the “smart” phone—that’s stumped her. It’s the smart phone, its glowing touchscreen and cartoonish icons, that’s turned her 75 years into what feels to her like 75 minutes.

Don’t get me wrong. She can answer the phone, and make calls. She can even text message, but this would require an entirely different newsletter to explain how long it took me to convince her to even try (she was always afraid she’d hit the wrong letters, as if that matters). I’ve even—and you won’t believe this—but I’ve even gotten her to FaceTime with me over the last year, even though she still doesn’t quite grasp the idea that she’s on speakerphone and doesn’t need to put the phone to her ear. And when she does, I get a full glimpse of what’s going on in her head. Literally.

But last week, she called me (on her house phone), distressed.

“J, I need you to teach me how to send pictures to people on my phone,” she said.

“You want to send someone pictures?”

“No,” she said. “But I want to know how to.”

So, I went to her house, and started the tutorial. First, I had to teach her how to take a photo. Then, I had to show her how to find the photo she’d taken. Then, I had to show her how to send it through text.

It took hours. HOURS. And she kept thanking me. Kept apologizing for not understanding this new language, this new (to her) technology. And I kept telling her it was fine. Because it was fine. As a matter of fact, it was better than fine. It was fantastic. Sure, there were frustrating moments, especially when she’d get frustrated with herself. And it was challenging for me to figure out new ways to explain things, reworking my own definitions to help her understand. To meet her where she was. We practiced and practiced, tried and tried, running through it again and again, me trying to help, her begging me not to. And eventually, that weird series of sounds we’ve all gotten used to came through. The sound of a cartoon droplet chimed from her phone, and the ding of a bell from mine. She’d sent. I’d received. She was happy. And I … was something else. I mean, I guess happy is one of the words I’d use. But I was also … full. Because I’d taught my mother something. I’d given the woman who has given me everything a new language. A new skill. A new opportunity to express joy. And in that moment, a moment where learning was recycled between the two of us like breath—she breathing out while I breathed in, only to breathe out again for her to inhale my breath, which was technically her old breath—life unto life, I realized that this is the true meaning of relationship. Of family.

Young reader, I want this for you. You know things your parents don’t know, just like they know things you don’t know. But the only way our specialties are activated is if we’re all open to learn, which means we all—yes, even your parents who are basically older kids—have to be willing to admit when we don’t know. Willing to make that call. Because it’s in the I don’t know where the new experience is. And it’s in the willingness to learn, where love feels electric.

And yes, she sends me pictures all the time.

And no, I can’t make out what any of them are.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 3, 2021

Rodney King Beating Was 30 Years Ago Today; Courtroom Sketches Now at Library

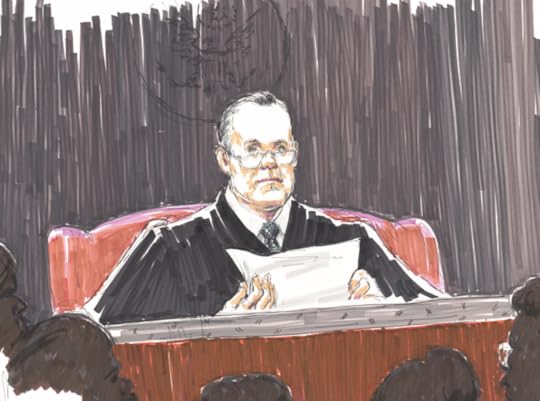

Rodney King on the witness stand. Artist: Mary Chaney. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by María Peña, a public relations strategist in the Library’s Office of Communications.

In a hushed Los Angeles courtroom, Rodney King recalled in a faint voice the blows he took from four white police officers wielding metal batons on March 3, 1991. King, who was Black, told a prosecutor that he tried to flee because he was “just trying to stay alive.”

As jurors leaned forward to hear King’s riveting testimony during that 1993 trial, Mary Chaney took to her sketch pad. Chaney, then one of the nation’s top courtroom artists, created 269 sketches from King’s federal and civil trials between 1992 and 1994. “It’s like walking a tightrope without a net,” she told the Los Angeles Times about the pressure she was under.

The beating of King was one of the most pivotal moments in recent American history. It took place 30 years ago today. The Library marks the occasion by announcing that it has acquired those sketches from Chaney’s estate.

“The sketches from the federal trial against the police officers for violating Rodney King’s civil rights and his civil lawsuit against the city of Los Angeles stand out as the type the Library should be collecting and making available to researchers,” said Sara Duke, curator of Popular and Applied Graphic Art.

Chaney, who died of cancer at 77 in 2005, would have been thrilled to see her artwork added to the Library’s collection of landmark court trials, said Lark Ireland, her daughter. Chaney’s sketches joins those of , Aggie Kenny, Pat Lopez, Arnold Mesches, Gary Myrick, Joseph Papin, Freda Reiter, Bill Robles, David Rose, Jane Rosenberg and among others.

“It gives me chills, it really does,” Ireland said in a recent phone interview. “Recognition was not her goal in life, she lived for her art; it was sacred to her.”

King’s beating — caught on tape by a witness who saw the event unfold from his apartment balcony — shocked the nation because it laid bare the problems of police brutality and racial bias in law enforcement, themes that are still relevant today.

King’s run-in with police began as fairly routine. He was unarmed but on parole for robbery when police attempted to pull him over, suspecting him of driving under the influence. Instead, he led them on a high-speed chase on I-210.The officers beat him viciously after he was finally stopped. Police log records would later reveal that one of the officers seemingly boasted about his role in the beating.

The four defendants listen to testimony in the Rodney King trial. Artist: Mary Chaney. Prints and Photographs Division.

The trials against officers Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, Stacey Koon and Ted Briseno are considered a critical moment in legal history. The acquittal on state criminal charges in 1992 unleashed five days of looting and rioting in Los Angeles, leaving more than 60 dead, thousands injured and about $1 billion in damages. Businesses left in smoldering ruins took years to recover. It became a landmark moment in U.S. culture.

Chaney did not begun her career in courtrooms, as she started out in commercial art. But cameras are generally forbidden in courtrooms, so sketch artists helped pull back the curtain and catch the essence of significant legal proceedings. At the suggestion of a colleague, she switched from commercial to courtroom art in the mid-1980s. She practiced by sketching her seven children.

“She was the worst cook in the world, but she was always painting or sketching, and we would be her subjects when she’d try to figure out something,” Ireland recalled.

Disciplined and passionate about her art and social causes, Chaney sketched life in downtown L.A., where her drawings of the homeless later became an exhibit. Her pieces were also exhibited at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles.

Chaney was “invisible” in the courtroom, but her poignant sketches became prominent, featured on television and on the the covers of major newspapers, magazines and law journals. She had already worked on many high-profile cases by the time the four LAPD police officers were indicted for excessive use of force in arresting King and would go on to document many more. Her career included trials ranging from that of “Night Stalker” Richard Ramirez to “Hollywood Madam” Heidi Fleiss, the Menendez brothers and O.J. Simpson.

U.S. Judge John G. Davies in King’s 1994 federal trial. Artist: Mary Chaney. Prints and Photographs Division.

Her work during the King trial shows dozens of indelible moments. On the stand, King described the racial epithets the police officers hurled as they beat, kicked, stomped, tasered and taunted him. When they were done, King had a fractured skull, broken bones and teeth as well as permanent brain damage. Others show King up close on the witness stand, pointing to a video clip or describing his arrest for drunken driving. Ireland still remembers an illustration where King was asked to read something out loud and he confessed that he was illiterate.

Chaney “had quite a passion for civil rights, so when the beating occurred… so many people were horrified about it, as she was,” said Ireland.

Still, she kept her composure through the testimonies, the grainy video of King’s beating and graphic photos of his injuries. The various trials stretched out, in all, for more than three years. After the officers were acquitted of criminal charges in 1992, she sketched the sentencing of officers Powell and Koon on federal civil rights charges in 1993, as well as the civil trial in which a jury awarded King $3.8 million in damages in 1994.

King, who had further arrests and convictions for traffic violations after the trials, accidentally drowned in the backyard pool of his home in Rialto, California, in 2012.

Chaney continued drawing all of her life. Even in hospice, Ireland said, when her mother could no longer string words together, she’d sketch. She’d like to be remembered, Ireland said, simply as someone who “showed up and did her job.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 1, 2021

The Aramont Library: Stunning Private Collection Now at Library of Congress

“Constellations,” 1959, Joan Miró, with commentary by poet Andre Breton. Aramont Library. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

This is a guest post by Stephanie Stillo, curator of Rare Books in the Rare Books and Special Collections Division. It appeared in slightly different form in the Jan.-Feb. issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

What makes a perfect book? Is it the typography? The illustrations? The binding? Is it what someone adds, like a signature, a note or a drawing? Or is it what they take away, like a perfectly trimmed edge?

For the collector of the Aramont Library, a recent donation of over 1,700 volumes to the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, the answer is clear: A perfect book is one that is unique, surprising or personal.

James Joyce’s hand-drawn map of Dublin. Aramont Library. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

It is a rare first edition of James Joyce’s “Ulysses” with a curious annotated anatomical drawing tipped in. It is a signed 23-volume set of the collected works of Joseph Conrad with a unique leather vignette on every cover. It is a 20th-century edition of the poems of Baroque poet Luis de Góngora with original illustrations and commentary by Pablo Picasso and bound by Paul Bonet. While beauty certainly resides in the eye of the beholder, it is quite easy to share the vision of the collector of the Aramont Library.

In private hands for over 40 years, the Aramont Library consists of 1,700 volumes of literary first editions, illustrated books, and an astonishing collection livres d’artiste (books by artists) by some of the most important artists of the 20th century. Many of the books in the collection are enclosed in fine bindings; stunning expressions of craft that are more appropriately described as works of art than simple bindings.

The library began in the early 1980s with signed and inscribed first editions of modernist literature, a genre that critically explored topics such as alienation, disillusionment and fragmentation in the industrial, postwar West. These range from the poetry of Miguel de Unamuno and Ezra Pound to the novels of William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, Virginia Woolf and Willa Cather.

Nothing captures the Aramont Library’s hunt for perfection better than the collection’s three first editions of Joyce’s bawdy, stream-of-consciousness novel “Ulysses,” first published in Paris in 1922 by Shakespeare & Company. Loosely based on Homer’s “Odyssey,” the novel follows Joyce’s protagonists as they meander the streets of Dublin one day in June, exploring the drama and heroism of everyday people. The rare, and highly sought-after, first editions in the Aramont Library include inscriptions, signed letters by Joyce, photographs, a rare copy of Joyce’s 1920 schema for his “dammed monster novel,” as well as a unique and unusual anatomical figure that corresponds to the structure of the book, perhaps in the author’s hand.

The heart of the Aramont collection is a thoughtful assemblage of illustrated books and livres d’artiste that span from the late 18th to 20th centuries. The Aramont begins its exploration of illustration with the most important Spanish painter and graphic artist of the Baroque period, Francisco Goya (1746-1828). Goya used the technique of printing to level piercing critiques about the world around him. His two most famous series, both in the Aramont, are “Los Caprichos” (1799), a visual critique of the hypocrisy and foolishness of the Spanish Royal Court, and “Los Desastres de la Guerra” (1810-20, published posthumously in 1863), a graphic and disturbing expose about the horrors of the Peninsular War.

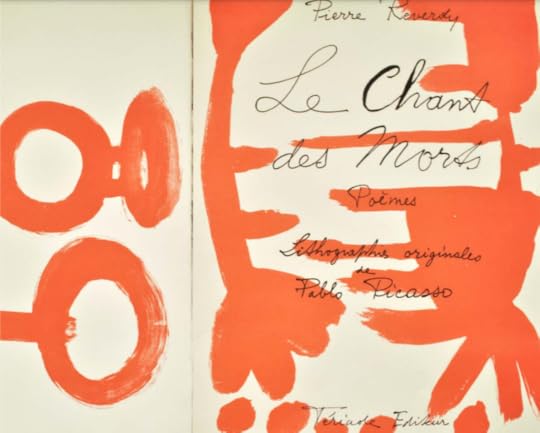

“Les Chants des Morts,” (“The Songs of the Dead”), 1948. Handwritten poems by Pierre Reverdy. Illustrations by Pablo Picasso. 1948. Aramont Library. Rare Books and Special Collections Division.

From the continental conflicts of the early modern period to the aesthetics movements of the 19th century, the Aramont Library focuses specifically on the illustration and bindings of the arts and crafts and art nouveau movements. Disillusioned with the impact of industrialization on the aesthetics of the everyday, notable artists and intellectuals like William Morris (1834-1896) sought to reestablish the close relationship between artists, craftsman and final product.

The Aramont demonstrates how the arts and craft movement held a special significance for book binders. From the bejeweled bindings of Sangorski & Sutcliffe to the intricate pointelle patterns of Doves Bindery, binders of the late 19th and early 20th centuries challenged the mass production of commercial binderies by crafting customized binding for everything from single books to multivolume sets.

The late 19th century also witnessed the rise of art nouveau. Defined by an artistic preference for the sensual, wild and unkempt, the art nouveau aesthetic shaped the appearance of everything from commercial advertising to furniture design until the start of World War I.

The impact of art nouveau in graphic art is best represented in the Aramont Library by the illustrations of Aubrey Beardsley. In 1894, Beardsley created illustrations for the English translation of Oscar Wilde’s play about the biblical femme fatale, Salome. Wilde’s play (by the same name) dramatized an evening of carnal desire that concluded in the decapitation of the itinerant prophet John the Baptist. Banned from stage performances until 1896, Beardsley’s illustrations offered the play its first visual performance through fantastic and erotic imagery that skillfully elucidated Wilde’s story of female domination, sexual desire and death.

Detail from an Aubrey Beardsley illustration from Oscar Wilde’s “Salome.” Aramont Library. Rare Book and Special Collections Divisoin.

The Aramont Library’s greatest strength is its assemblage of livres d’artiste, a corpus of material that reveals the deep and meaningful collaborations between artists, authors and publishers during the 20th century. These range from the early post-Impressionist work of Pierre Bonnard and Henri Matisse to the fauvist revelations of George Rouault and André Derain. From the geometric cubism of George Braque and Jacque Villon to the unbridled surrealist visions of Marc Chagall, Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning. For example, “À Toute Épreuve” (1958) was a visual meditation on the surrealist poetry of Paul Eluard.

In the early 1940s, Swiss art dealer and publisher Gérald Cramer enlisted the expert vision of surrealist painter Joan Miró to illustrate Eluard’s prose. The now-iconic “À Toute Épreuve” was the result of a 10-year collaboration between the artist, poet and publisher, cut short only by the death of Eluard in 1952. The result was a monument to the book as an art object. To create distinctive graphic texture to the images that would interlace the letterpress pose, Miró glued wire, stones, bark and sand to his woodcuts, assembled discrete collages from old prints and added visual embellishments from mail order catalogs.

Many of the livres d’artiste in the Aramont Library are enclosed in bespoke bindings that meditate on the major themes of the text or the visual contribution of the artist.

Rose Adler’s binding for Jean Cocteau’s “The Human Voice,” with illustrations by French expressionist Bernard Buffet, used an assemblage of dyed leather and abalone shells to depict a large rotary phone, a gesture to Cocteau’s emotionally charged narrative about a woman on the phone with her former lover. The Aramont Library also holds six bindings by the most celebrated binder of the 20th century, Paul Bonet. This gathering includes Bonet’s famous sunburst pattern. Perfected by Bonet in the 1930s and 1940s, the pattern uses a combination of gold lines and colored leather to create the illusion of dimensionality and depth. In the Aramont Library, Bonet’s sunburst announces George Rouault’s “Circus of the Shooting Star,” an illustrated rumination on human frailty as seen through the daily lives of circus performers, a common theme for many post-impressionist artists.

Cover of “Circus of the Shooting Star,” by George Rouault, bound by Paul Bonet. Aramont Library, Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

When taken as a whole, the Aramont Library is both a measure of Western creativity over the last two centuries and a reflection of a collector’s pursuit of the perfect balance between book design, illustration and binding. We in Rare Book look forward to sharing more with you about this extraordinary collection in the months and years to come.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

February 25, 2021

Afro-Latinos: Shaping the American story

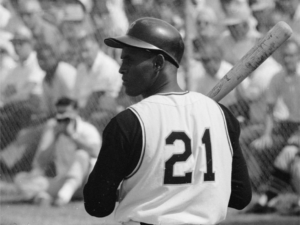

Roberto Clemente at bat for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1967. Photo: Jim Hansen. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by María Peña, a public relations strategist in the Library’s Office of Communications.

No discussion around Black History Month would be complete without exploring the significant contributions of Afro-Latinos to American culture and society. The Library provides a rich sampling of some of these icons who have enriched the national mosaic.

Latinos can be of any race, and according to the Pew Research Center, about 25 percent of Hispanics in the U.S. self-identify as Afro-Latinos. As members of the African diaspora, they have faced discrimination for being black and alienation because of their language and accent.

Orlando Cepeda, the Hall-of-Fame first baseman from Puerto Rico, summed it up this way after a brilliant 17-year career in Major League Baseball from 1958 to 1974: “We had two strikes against us: One for being black, and another for being Latino.”

Spanish-speaking Africans were present in North America before the arrival of English settlers and Afro-Latinos came to be an integral part of American history. Their stories and struggles interweaved with those of Africans enslaved by English settlers and added to the nation’s cultural tapestry. Still, because white society seldom sought to understand or differentiate differences between Blacks, Afro-Latinos have often been underreported in the news media or are barely mentioned in history textbooks.

“Afro-Latinos have had a long history and strong presence in U.S history since the mid-16th century and very few Americans are aware of the term ‘Afro-Latinos,’ ” said Carlos Olave, head of the Hispanic Reading Room.

Nevertheless, as D.C. AfroLatino Caucus founder Manuel Méndez points out, the world would not be the same without prominent Afro-Cuban musicians like Mario Bauza. And no one can forget Johnny Pacheco, the Dominican-American music legend who co-founded Fania Records in the 1960s and helped create the genre of music known today as salsa. When he died on Feb. 15, the world lost an icon. There was also the heroic efforts of Dominican-born Esteban Hotesse, a Tuskegee Airman during World War II, to integrate the military.

Here are just a few more of the names who have changed American history, many of whom you can find in the Library’s collections.

— Puerto Rican historian Arturo Alfonso Schomburg was a key intellectual figure in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and spent his life championing Black history and literature. His collection of books, documents and artifacts from and about Black history from around the world helped establish the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem in 1926, within the New York Public Library.

Before Jackie Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color line with the Dodgers in 1947, several Afro-Cuban players had made inroads decades earlier for people of color in the nation’s pastime, including Estevan Enrique Bellán, Rafael Almeida and Armando Marsans. During the ensuing decades, Roberto Clemente, Orlando Cepeda, Minnie Miñoso and the Alou brothers (Felipe, Manny and Jesus) were among the sport’s most important Afro-Latino players, setting the stage for future generations to become some of the brightest stars in the game. In 2020,10.7 percent of MLB’s entire roster was from the Dominican Republic alone.

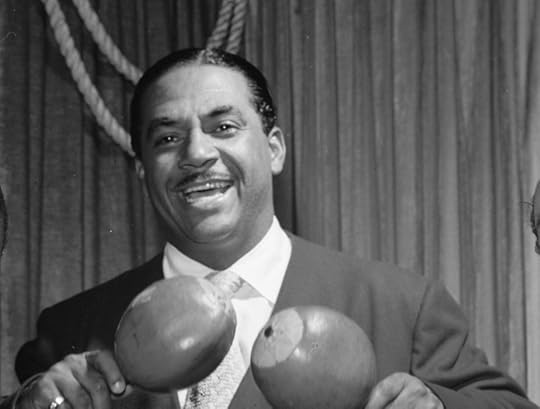

Machito, performing in 1947. Photo: William P. Gottlieb. Prints and Photographs Division.

— The arts and entertainment world of the early to mid-20th century was flavored with the rhythms of Afro-Latino mega stars like Sammy Davis Jr. (his mother, Elvera Sanchez, was of Afro-Cuban descent), Celia Cruz, Machito (Frank Grillo) and Negrura Peruana. Machito fused traditional Cuban dance rhythms with big-band arrangements to dominate the post-war Latin music scene during the Golden Age of Latin Music; the Library has a huge trove of his papers. Cruz, also known as the “Queen of Salsa”, won numerous awards throughout her 60-year career, with sold-out performances where her battle cry “¡Azúcar!” (“Sugar!”) alluded to African slaves working in sugar cane plantations in her native Cuba.

As in baseball, these Afro-Latino artists founded a platform so broad that is taken for granted today; Mariah Carey, Rosario Dawson, Esperanza Spalding and Zoe Saldana and just a few names to drop.

—In literature, Afro-Latino authors have added their voices to the national dialogue for years, with their works attracting an international following. The list includes Junot Díaz, (“Drown,” “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao”) born in the Dominican Republic and raised in New Jersey; Brazilian author Paulo Lins (“City of God,” adapted to film in 2002); Dominican-American author Elizabeth Acevedo (“The Poet X,” winner of the National Book Award For Young People); Veronica Chambers, the Panamanian-American journalist and author; and Puerto Rican authors Mayra Santos Febres and Dahlma Llanos Figueroa.

–In science, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson has talked about his Afro-Latino heritage as the son of a Puerto Rican mother and an African-American father and has written about his experiences with racial profiling. Growing up in the Bronx, deGrasse Tyson developed a passion for astronomy after a visit to the sky theater at the Hayden Planetarium at the age of nine. He became the fifth director of the New York City-based planetarium in 1996, and he continues to promote science literacy and to popularize science through lectures, seminars, and national book tours.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

February 22, 2021

Black History Portraits: The Famous and The Forgotten

William Pettiford, 1908. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Elizabeth Gettins, a digital library specialist in the Digital Collections Management and Services Division.

William R. Pettiford was born in Birmingham, Alabama, coming of age in the turbulent years after slavery ended and Reconstruction was a violent, uncertain business. In this tumultuous environment, he was smart, studious and devoutly religious. Early in his career, he worked as a minister and teacher in various towns across Alabama. In 1890, when he was in his late 40s, he founded the Alabama Penny Savings Bank. which greatly spurred black economic development in the region, with an emphasis on home ownership. Starting out with initial deposits and stock of $2,500, in 20 years deposits were $420,000 (roughly $11 million in 2021). He’s credited with being one of the most significant Black bankers and lenders of the era.

His is one of many portraits in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division’s new digital gallery of African American Portraits, the most recent addition to the digitized African American Perspectives Collection. It’s a fascinating collection of nearly 800 items that show the famous and the forgotten in a generation of Black Americans who strived, fought, prayed and kept making a way out of no way during the early decades of freedom.

Taken together, the portraits show the character and humanity of the individuals who fought to better their circumstances against the headwinds of bigotry, enforced poverty and discriminatory laws. Scrolling through the images, you’ll see well-known social activists and religious leaders including Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Alexander Crummell. However, you may be surprised to see so many unfamiliar faces that accomplished so much and made such impressive inroads.

This mosaic of faces brings together those that came before us, from many places across the country and from many walks of life. Together, they form the story, both told and untold, upon which future generations built their own successes. It is our hope that this gallery will encourage further research into the lives of these intriguing historical figures and to give them the credit they so richly deserve.

In addition to Pettiford, here are two more stories. The larger catalogue, and the stories they contain, are yours for the seeking.

Gertrude Bustill Mossell, 1902. Prints and Photographs Division.

Gertrude Emily Hicks Bustill was born in Philadelphia in 1855 to a prominent African American family during the last of the antebellum era. She would lead a remarkable life over her 92 years, playing an active, socially-engaged role in all of it. She was a child during the Civil War. She saw Blacks gain freedom from slavery but then be forced into the “separate but equal” lie of segregation. She lived through World War I and worked to help get women the right to vote. She endured the Great Depression, watched World War II unfold and lived to see the United States emerge as the world’s greatest power. She died in 1948, the year after Jackie Robinson integrated professional baseball.

Her father, who had worked on the Underground Railroad to help enslaved Blacks escape to freedom, encouraged her education from an early age. It was a rare opportunity for a woman in that era. She worked her way into being a journalist, author, teacher and activist who strongly supported black newspapers and advocated for more black women to enter journalism. She served as a writer and editor for several newspapers and magazines and published a number of books.

When she married, it was to Nathan Mossell, a prominent Black doctor who helped co-found and then direct the city’s Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital and Training School. She was an outspoken advocate for Black women in particular and an ardent supporter of all women’s right to the ballot. She was 65 when the 19th Amendment passed and she was finally eligible to vote.

By the time she died in January of 1948, only part of her life-long goal of a fair life for African Americans had been achieved, but she had left in an indelible mark in her city.

Robert Reed Church. Prints and Photographs Division.

Robert Reed Church was an imposing figure who rose from slavery to become one of the richest and most influential Black men in the South in the late 19th century – and his oldest daughter, Mary Church Terrell, became one of the most important educators, activists and female suffrage advocates in American history. Her papers are at the Library and you can help digitize them in this month’s By the People Transcribe-A-Thon.

Church, born in 1839 in north Mississippi, was the son of slave-owner Charles Church and one of his enslaved women, Emmeline. Charles Church owned and piloted steamboats. Emmeline Church died when Robert was 12. He said later in life that his father had never treated neither him nor his mother as slaves — but his father never acknowledged him as his child, didn’t have him educated and only allowed him to work on his steamships in menial jobs that were reserved for Blacks.

His break in life came in the Civil War when Union troops seized his father’s ship (with him on it), and then dropped off the crew in Memphis. From there, Church began to run a series of saloons, shops, stores and buy land that, over time, made him a fortune. In the 1866 riot by white mobs in Memphis – 46 Black people were killed, an unknown number of women were raped, a dozen churches were burned – whites shot Church and, believing him dead, left him. He survived. A few years later, a sheriff shot and wounded him yet again.

Undaunted, he became a hugely influential city booster and founded Solvent Savings Bank & Trust Company, the first black-owned bank in the city, which extended credit to Blacks so they could buy homes and develop businesses. As a philanthropist, he also used his wealth to fund and develop prominent parks, concert halls and entertainment facilities for Blacks who were excluded by racial segregation from nearly all other amenities. President Theodore Roosevelt spoke at one of his venues, as did Booker T. Washington. W.C. Handy performed there.

By the time Church died in 1912, his family was an institution in city life. His children continued the family tradition of education, service and devotion to civic causes and African American achievement.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

February 18, 2021

Kluge Prize Winner Danielle Allen Hosts “Our Common Purpose”

Danielle Allen. Photo: Laura Rose.

This is a guest post by Andrew Breiner, a writer-editor in the Kluge Center.

Danielle Allen, winner of the Library’s 2020 Kluge Prize for Achievement in the Study of Humanity, will host a series of exciting conversations at the Library to explore the nation’s civic life and ways that people from all political beliefs and social causes can build a stronger, more resilient country.

The series is called “Our Common Purpose—A Campaign for Civic Strength at the Library of Congress.” It consists of three public events this spring that are free and open to everyone. Each event will be accompanied by a workshop for K-12 educators and public librarians, in which teachers from across the country will connect, explore, experiment and create new ways of making civic ideals come to life in their classrooms.

The American Academy of Arts & Sciences is supporting Our Common Purpose and recently released a report, co-edited by Danielle Allen, “Reinventing Democracy for the 21st Century.”

The series begins March 11 with an event highlighting civic media as a promising counterpoint to the polarizing universe of social media. The second event, in April, will explore how voting systems can be a deciding factor in political decision-making, and how they might be reformed. The final event, in May, will look to history and search for ways we can create an inclusive narrative of America’s past. Each will feature Danielle Allen as the moderator with leading thinkers in social and civic media, reform in political institutions and the American historical experience.

The poster for the campaign, created by artist Rodrigo Corral, showcases the shared iconography of American civic life as well as the Juneteenth flag, a symbol that is known to some, but unknown to many others. This illustrates the theme of invisibility – that not everyone’s American experience is broadly understood or apparent.

“The art celebrates so much of what the Kluge Prize and Danielle Allen stand for: togetherness, connectivity, action, and above all else the bonds we have in our communities no matter our differences,” Corral said.

Allen, a native of Takoma Park, Maryland, grew up in California and is a multi-talented academic, political theorist, author and columnist. She is the James Bryant Conant University Professor at Harvard University and Director of Harvard’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics. Librarian Carla Hayden announced Allen as the Kluge Prize honoree last June. She was awarded the prize for her internationally recognized scholarship in political theory and her commitment to improving democratic practice and civics education. Her books include “Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Defense of Equality,” “Why Plato Wrote,” and a memoir about her cousin’s tragic experiences in the criminal justice system, “Cuz: The Life and Times of Michael A.”

The Kluge Prize recognizes the highest level of scholarly achievement and impact on public affairs and is considered one of the nation’s most prestigious award in the humanities and social sciences.

“At a time when trust in both civic and scientific institutions seems to be at a low point, Allen’s research, writing, and public engagement exemplify the societal value of careful scholarship and inclusive dialogue,” Hayden said. “Her engagement with public policy issues, including societal responses to the Covid-19 pandemic, demonstrates the possibility and value of careful, judicious, and rational deliberation among individuals from multiple academic disciplines and vastly different political backgrounds.”

Here’s the schedule of events.

Using Civic Media to Build a Better SocietyMarch 11, 2021

Panelists will explore the role of information in democratic society and addressing the challenges citizens face in identifying trustworthy sources of information in the digital age. They will consider the potential of civic media to inform and educate within the context of the broader social media ecosystem, where the incentives are to spread information regardless of its truth or value. Panelists will consider what civic media looks like and how it can it compete with social media.

Moderator: Danielle Allen

Panelists:

Talia Stroud (University of Texas) is a nationally-renowned expert on examining commercially viable and democratically beneficial ways of improving media.

Brendesha Tynes (University of Southern California) is a leader in the study of how youth experience digital media and how these early experiences are associated with their academic and emotional development. She is also interested in equity issues as they relate to digital literacy.

Richard Young is the founder of CivicLex, a non-profit that is using technology, media, and social practice to build a more civically engaged city. CivicLex aims to build stronger relationships between citizens and those who serve them.

How Political Institutions Shape Outcomes and How We Might Reform ThemApril 15, 2021

In the U.S., political institutions are often seen as neutral, but in fact they reflect choices and compromises about how we balance between majority and minority interests. Panelists will look at the way different systems of electoral decision-making in a democracy can, by themselves, lead to very different outcomes, and what can be done to reform them in ways that result in more responsive and deliberative legislative bodies.

Moderator: Danielle Allen

Panelists:

Lee Drutman (New America Foundation) is an influential and prolific author on reforming political parties, electoral systems and Congress.

Katie Fahey (Of The People) leads an organization dedicated to pursuing reforms to empower individuals in the political system.

Cara McCormick (National Association of Nonpartisan Reformers) is an activist and leader of organizations dedicated to electoral reforms at all levels.

Finding a Shared Historical NarrativeMay 13, 2021

Speakers will discuss the changing interpretations of the nation’s founding documents and the principles they were founded upon. They will also explore the tension between celebrating what is good about the U.S. and its history, while addressing the exploitation and inequality that are also part of the American legacy.

We have not finalized the panelists for this program

In addition, late in the year the Library will be reaching out to public librarians across the country to explore ways in which they guide citizens of all ages in finding credible information on the internet. Hundreds of librarians will participate in six weeks of moderated, online discussion. After these six weeks of conversation, a smaller, representative group of librarians will share with Danielle Allen and the president of the American Library Association a report that summarizes the group’s insights on separating fact from fiction on the internet.

“Our Common Purpose” featuring the Juneteenth flag with one star. Artist: Rodrigo Corral.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers