Library of Congress's Blog, page 46

April 12, 2021

Medieval Pandemic Cures That Were…Medieval

Illustration from “Herbarium.” Rome, 1481. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

This intriguing look into the medical practices of Europe some 600 years ago was written by Andrew Gaudio, a reference librarian in the Researcher and Reference Services Division.

As the world grapples with containing the COVID-19 pandemic with a range of vaccines, each with varying rates of effectiveness, it’s worth remembering that cure-alls for deadly pandemics have often proven to be more of a mirage than a reality.

The Library’s collection of medical texts from the ravages of the bubonic plague in 14th -century Europe, known as the Black Death for the color of the swollen lymph glands it caused, are an uneasy reminder of this, showing that the best practices of the era would horrify us today.

Many of these volumes are found in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Also, some medieval medical texts have been edited and reprinted and can be found in the Library’s general collections. They offer a window into an earlier time when even the most sophisticated doctors lacked knowledge of germ theory and microbiology. Medieval physicians had little to work with other than their own observations and past experiences in treating different illnesses; a deadly virus like the plague simply overwhelmed them. Mortality rates for the most virulent forms of the disease were reportedly as high as 95 percent.

Medical reference journals of the time show “cures” that could have helped only a little, and in some cases greatly exacerbated their patients’ suffering. Plasters made of various herbs (including, we must report, excrement) were common as treatment for buboes, as the painfully-swollen sores were called. It was thought that the technique of “bleeding” a patient in a bid to remove excess blood would restore the balance of the humors or bodily fluids of the patient to its normal state. From ancient times up to the 19th century, it was thought that the bodily fluids consisted of four humors (black bile, yellow bile, phlegm and blood) and that health could only be achieved when all humors were present in the same proportions. Bleeding a patient removed an excess amount of blood and therefore was thought to restore the humors of the body to their proper levels.

The location of bloodletting was thought to be relevant to the ailment. In one reference volume dating to about 1410 — a sort of early almanac — the authors published a rough drawing of a “vein man,” detailing where and how to bleed a patient. Each vein and location on the body was provided with instructions as to how the bleeding should be carried out, depending on the medical problem.

A “vein man” drawing from about 1410, published in southern Germany. Book and Special Collections Division.

In their quest for a cure, some doctors reported more success than others. French physician Guy de Chauliac, who was personal physician to Pope Clement VI, claimed that he was afflicted with the plague but had cured himself.

De Chauliac’s narrative of this event is found in “Inventarium sive chirurgia magna,” Latin for “The Inventory or the Great Surgery,” published in 1363. A modern printed edition of this text is available in the Library’s general collections.

Here’s his tale. The parentheticals are mine, to help modern readers understand the text.

Regarding a cure, venesection [bloodletting], purging [most likely an emetic or a laxative] and electuaries [medicine mixed with honey] and syrupy cordials were available. The external buboes were softened with figs and cooked onions ground up and mixed with yeast and butter. Afterwards, the buboes would open and were healed. The sores were bled by applying a cupping glass, sliced open, and cauterized.

And I, to avoid defaming my reputation, did not dare to flee. With constant fear I protected myself with the preceding methods as much as I could. Nevertheless, towards the end of this mortality [the plague], I developed a continual fever with a bubo in my groin and I was sick for almost six weeks, and I was in such danger that my friends believed that I was about to die. By softening and treating the sore, as I have said, I escaped death by the command of God.

This comes from the book “Canonical medicine: Gentile da Foligno and scholasticism,” by Roger French which is in the Library’s general collections. A prominent doctor in 14th-century Italy named Gentile da Foligno was famous for treating plague patients. He ultimately died of the plague in 1348 in his quest to help the sick. That is heroic, no doubt, but some of his recommendations will cause a 21st-century reader to raise an eyebrow.

Here’s one of his mixtures for a salve: extract from an umbelliferous plant (the parsley family, including carrots and celery), the root of a lily and human excrement. It could be that of the patient. These ingredients were to be mixed together and rubbed onto the bubo. Da Foligno thought that this concoction would aid in withdrawing fluids from the sores and would therefore reduce swelling. Needless to say, this concoction actually would have worsened the patient’s condition.

The use of plants and herbs for plasters and aroma therapy were common to the era. Guidebooks on medical plants, called herbals, identified and illustrated their uses and properties. These books were prevalent in the medieval period.

In “Herbarium,” a manuscript printed in Rome in 1481, a cure for gout is offered. The text, translated from Latin: “For gout in the big toe and gout in the knee. The peridcalis plant is boiled in water and with that water you will warm your foot or knee. Next you will place on your feet or knees the crushed plant [mixed] with hog fat in a cloth. You will heal remarkably.”

That last observation, alas, is likely more hope than medical reality.

April 9, 2021

Prince Philip at the Library of Congress

Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh and husband of Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, died on Friday at Windsor Castle in England.

Prior to her ascension to the throne, then-Princess Elizabeth and the Duke visited America and made a stop at the Library. Here’s an account of their visit from our Library of Congress Information Bulletin, v.10 n.45, November 5, 1951:

Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh visiting “Shrine” documents at the Library of Congress, November 1951. Library of Congress Archives

Their Royal Highnesses, Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh, expressed great pleasure that [the Library of Congress] was included in their tour on Friday, and the Princess was deeply impressed with the fact that so many staff members turned out to greet them. Mr. Clapp conducted the 20-minute tour of [the Library], which included viewing the Main Reading Room from the Gallery and exhibits on the second floor.

In addition to Their Royal Highnesses, the Royal party included the British Ambassador Sir Oliver Franks and Lady Franks, Canadian Ambassador Hume Wrong and Mrs. Wrong, Canadian Secretary of State for External Affairs Lester Pearson and Mrs. Pearson, the Princess’ Lady in Waiting, Their Royal Highnesses’ Equerry, the Secretary of the Royal Household, and Mr. John F. Simmons, chief of protocol in the State Department. Official photographers and press representatives also accompanied the party. LC staff members who were presented to the Royal couple were: Messrs. Buck, Mearns, Andreassen, Adkinson, Wagman, Keitt, Fisher, Gilbert, Krould and Webb.

Besides viewing the Main Reading Room and the Shrine documents, the visitors saw the memorabilia of the Presidents, the “Milestones of American Achievement” and other regular LC exhibits, and a special display arranged in their honor, which included: A letter of condolence on the death of President Lincoln from Queen Victoria to Mrs. Lincoln; a letter from Thomas Jefferson to James Monroe calling attention to the importance of friendship with Great Britain; a letter in King George V’s handwriting to President Wilson expressing “deep satisfaction” that the two English-speaking nations were working together; and a sketch of the Battle of Trafalgar between Lord Nelson and the combined fleets of France and Spain, with a letter describing the action.

Both the Princess and the Duke expressed keen interest in the exhibits. They had learned the Gettysburg Address and were pleased to see the original; the Princess was particularly interested in Queen Victoria’s letter, asking how LC happened to have it; the Duke studied the sketch of the Battle of Trafalgar; and both of them asked questions about the Shrine documents and the new preservation processes. It is reported that they were still talking about the LC visit and the fact that so many people were there to see them when they went up into the Capitol after seeing the Supreme Court Building.

Our collections include several more images of Prince Philip and Queen Elizabeth — including a wedding portrait and a Herblock cartoon.

Thanks to Library of Congress archivist Cheryl Fox for finding this account.

April 7, 2021

More Jazz, More Mingus? The Library Has It

The following is a guest post by Music Division archivist Dr. Stephanie Akau; it originally appeared on the In the Muse blog.

Charles Mingus, circa early 1950s. Photo: Not known. Music Division.

The Library was delighted to recently welcome four additional holograph manuscript scores of Charles Mingus, the legendary jazz double bassist, pianist, composer and bandleader, to our existing collection of his life’s work.

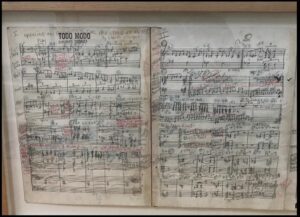

They came as a gift from Sue Mingus, his widow. I recently reprocessed them with processing technician Pam Murrell. The scores that comprise this gift are “Alive and Living in Dukeland,” “Three or Four Shades of Blues,” “Cumbia and Jazz Fusion” and “Todo Modo.”

“Alive and Living in Dukeland” is one of many of Mingus’s tributes to Duke Ellington, who had an enormous influence on Mingus and countless other musicians. Mingus performed briefly with Ellington’s band before a physical altercation with trombonist Juan Tizol lead to his dismissal in 1953.

Mingus composed and recorded the other three charts, “Three or Four Shades of Blues,” “Cumbia and Jazz Fusion,” and “Todo Modo” in the mid-1970s, shortly before he died from complications of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). “Three or Four Shades of Blues” was the title track of an album assembled from March 1977 recording sessions under a contract from Atlantic Records.

The other pieces on the LP are “Noddin’ Ya Head Blues” and “Nobody Knows,” along with Paul Jeffrey’s new arrangements of Mingus standards “Better Git Hit in Your Soul,” and “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat.” Mingus responded negatively to the “Three or Four Shades of Blues” LP but listeners loved it; the album sold 50,000 copies in just two months. It was a Cadence magazine Editor’s Choice for one of the top albums of 1977, a list that included Cecil Taylor’s “Dark to Themselves,” Gerry Mulligan’s “Idol Gossip,” Dexter Gordon’s “Swiss Nights,” and the reissue of the Red Norvo Trio with [Tal] Farlow and Mingus.

The 1977 Atlantic Records contract allowed Mingus to expand his ensemble for “Cumbia and Jazz Fusion,” which is nearly a half-hour long and takes up the entire side of an LP. The recording features congas and South American percussion, and the ensemble even includes a bassoonist, Gene Scholtes. The score is comprehensive and a listener can follow along with the recording.

“Todo Modo” is on the flipside of the “Cumbia” LP. Mingus had written the music for director Elio Petri’s 1976 film “Todo Modo,” also known as “One Way or Another” in the United States (not to be confused with the Blondie song released a couple years later). However, Petri did not use Mingus’s music or his arrangements for the film. Instead, he asked Ennio Morricone to compose a new soundtrack. Critics enjoyed the Cumbia/Todo Modo album, one writing that Mingus was “a national treasure” and that “ ‘Todo Modo’…swing[s], struts, sings and sighs.”

Charles Mingus. “Todo Modo,” holograph score. Music Division.

The condensed scores are heavily annotated with instrumentation notes, as shown in the photo of “Todo Modo,” and performance directions explaining who is supposed to solo and when, seen in “Cumbia and Fusion.”

Charles Mingus. “Cumbia and Jazz Fusion,” holograph score. Music Division.

The annotations provide a glimpse into Mingus’s compositional process. The collective improvisation, in which more than one person improvised at a time, that characterized his music may sound chaotic at times, but these scores demonstrate how clearly Mingus conceived of a piece’s structure. They are a welcome addition to the collection!

When the Library is once again open to the public, the Charles Mingus Collection is available for research in the Performing Arts Reading Room. For more In the Muse posts about Mingus, see Pat Padua’s “Meditations on Mingus” and Pam Murrell’s “The Thingus About Mingus”.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

April 5, 2021

Jason Reynolds: Grab the Mic April Newsletter.

It’s April, which means it’s … NATIONAL POETRY MONTH! Honestly, this might be my favorite month of the year besides February, and July. Oh, and there’s December, which is my birthday month. And there’s something about September, too. Anyway, April is here. Which means poetry is here. Poetry is always here, but during April it’s pushed onto the main stage to shine. So, this newsletter will be a poem. I’ve been hiding out in the woods working on some things, and, well … that’s where my head is.

It’s April, which means it’s … NATIONAL POETRY MONTH! Honestly, this might be my favorite month of the year besides February, and July. Oh, and there’s December, which is my birthday month. And there’s something about September, too. Anyway, April is here. Which means poetry is here. Poetry is always here, but during April it’s pushed onto the main stage to shine. So, this newsletter will be a poem. I’ve been hiding out in the woods working on some things, and, well … that’s where my head is.

BREWSTER, NY

it’s cold in the morning.

my bones are late for work

and so am i. and so i am

preparing a wood burning stove,

twisting a section of yesterday’s

and today’s times into wick and fuse,

tucking it into an iron belly,

lying logs on top and lighting.

learning a new way to warm.

it looks like sun blazing through

a small window and bullies the shiver

from the room. my bones crackle.

i am thawing and grateful for kindling,

melting awake in the morning,

glad to burn up bad news, first thing.

and trying not to think about

what else is up in flames locked

behind that door. because

it’s cold here. and i have too much

work to do to think about what’s been axed

for me to feel my fingers.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 31, 2021

New Book Draws on the Library’s Bob Hope Collection

Bob Hope and his USO troupe visiting a hospital ward in the South Pacific (from left) Tony Romano, Jerry Colonna, Bob Hope, Patty Thomas, and Frances Langford, 1944. Bob Hope Collection.

This is a guest post by Becky Brasington Clark, Director of Publishing.

In the spring of 1941, Bob Hope couldn’t understand why his producer was pushing him to broadcast his hit radio show from a California military base instead of the Burbank studio. He was a celebrity, a big star, a comedian who worked on stage, radio and film. And yet his producer, Al Capstaff, wanted Hope to perform in front of an audience of enlisted soldiers at a busy training installation known as March Field.

The comedian reluctantly agreed, taking the stage on a sweltering day in a gym packed with nearly 2,000 soldiers. There was no air conditioning, no cue cards. But the thunderous sound of laughter introduced radio’s hottest star to his most important audience.

After Pearl Harbor was bombed seven months later, thousands of men and women volunteered or were drafted for the war effort. Hope could have enlisted as a lieutenant commander in the Navy, but President Franklin D. Roosevelt had other ideas. Hope could best serve his country by entertaining the troops.

From 1941-1944, Hope and a core group of regulars (Frances Langford, Jerry Colonna, Tony Romano, Patty Thomas and Barney Dean) performed the radio show from a different armed forces base nearly every week during the broadcast season.

They also traveled to the front, enduring long, uncomfortable flights in military aircraft, tropical downpours, giant mosquitoes and incoming bombs to deliver laughs, music and news of home.

They took the show to Britain, North Africa, and Sicily in the summer of 1943 and to the South Pacific and Australia in the summer of 1944. Impromptu performances in remote locales and hospitals supplemented scheduled shows in each area.

These performances inspired thousands of letters and postcards of appreciation from soldiers, nurses, wives and parents. Some were penned on paper bags, coconut shells and toilet paper, others addressed only to “Bob Hope, in care of Paramount Studios,” or “Bob Hope in Hollywood.”

Hope answered as many of them as he could, sending holiday cards, autographs, toiletry kits—even fruitcakes—to the soldiers, and he relayed messages from them to their parents, spouses, and sweethearts.

Hope with secretary Marjorie Hughes. Hope Collection.

Meticulously organized by Hope’s secretary, Marjorie Hughes, this remarkable body of correspondence is among 557,000 items now preserved in the Bob Hope collection at the Library. A new book, “Dear Bob….Bob Hope’s Wartime Correspondence with the GIs of World War II” captures and celebrates the mutual affection and admiration between Hope and the service members he would entertain over the course of five decades.

Hope was a celebrity, but he didn’t act like one when he visited the troops. He mingled with the soldiers, listened to their complaints and ate with them in the mess halls.

Eager to give the “G.I. Joes” the best laughs possible, Hope sent writers to the bases in advance of the performance to learn specifics about the soldiers and their lives, working the information into jokes that seemed tailor-made for the moment.

Written and compiled by Hope’s longtime staff writer Martha Bolton, along with his daughter, Linda Hope, “Dear Bob…” paints a vivid picture of a typical performance. “Whenever a Bob Hope monologue touched on familiar topics such as military food, physical demands, or dealing with superiors, the laughter was deafening” they write. “The soldiers couldn’t figure out how Bob knew them so well. Had he been trailing them around the base, eavesdropping on their bunk-side complaints, listening to them in the chow lines? And how did he know which officers were the most demanding, or that the camp had just had an air raid the night before?”

Some of the letters he received over the years:

Aug. 9, 1944

The jolt in the arm which we so sorely needed was supplied with your humorous hypodermic. I cannot express in adequate English how much your visit meant to all of us. . .

Jan. 22, 1945

There is nothing which makes a man happier than good music from his favorites and a heap of laughs. My morale goes up forty points whenever I hear one of your programs.

Undated

A sailor laughed so during your show at the canteen Thanksgiving afternoon that he split his pants—the back seam from waist to——. I know. I am the girl who sewed it back.

Some of the letters to Hope. David Jackson, Library of Congress.

Hope always made time to visit with the wounded, often proving the adage that laughter is the best medicine. Men who hadn’t spoken or interacted since their injury responded to him immediately.

As Bolton and Linda Hope recall, “The wounded appreciated how he would look beyond their injuries to see the man (or woman) bearing them. Whatever the prognosis, no matter how grim the situation, Bob’s goal was to get a smile or laugh out of each of them, which wasn’t always easy. For some, it was their first laugh in months.”

Oct. 15, 1944

I’m in a hospital and was almost dead. But I started to get well, and last night I saw a short about you and Lana Turner frying steaks, and Betty Hutton and Judy Garland. I laughed myself almost sick again, but you really lifted up my spirits. Thanks a million, Mr. Hope, and God bless you.

May 21, 1946

I had just came from Guam on a stretcher a couple days before you and your troupe arrived and I mean I really appreciated the way you acted.

March 7, 1948

….on the morning of the day that I saw you I had been told that I could take my choice of two things: keeping what legs I had left with the probability of never walking again, or having them amputated with the possibility of walking with artificial limbs. I’ll not lie . . .I was plenty scared . . . I know of no other man whom I have ever encountered who could have so well lifted a lowered man’s spirits than you did that day. .. You stayed within range of my hearing about 20 minutes that day, and if I live to be a million, I will always treasure it as the outstanding day of my life.

Hope knew that many of the young men he entertained wouldn’t make it home alive. While he couldn’t erase the specter of death, he managed time and again to give the soldiers of World War II a brief respite of non-stop jokes amid gales of laughter.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 29, 2021

Library Photographer Carol Highsmith: Documenting the Nation’s Beauty and Resilience

Yardi Gras in New Orleans, replacing Mardi Gras during COVID. Photo: Carol Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by María Peña, a public relations strategist in the Library’s Office of Communications.

Even in the midst of a pandemic that has buried dreams and kept a tight grip on the nation’s psyche, Library photographer at large Carol M. Highsmith wants us to fall in love with America — to see its washed-face beauty and, through it, all that unites us.

Although she’s traveled in every state shooting life in urban and rural settings since 1980, her road trips during the COVID-19 pandemic have been challenging. Her vivid photographs have captured crowd-less landmarks and street scenes, empty highways and shuttered businesses. But, she says, the images also denote American resilience. You just have to look closely.

Carol Highsmith (and friend). Prints and Photographs Division.

Having traveled to the former Soviet Union in the 1970s and later through China and Europe, Highsmith, 74, says she developed a deeper appreciation for the U.S.

“Obviously a lot of small towns are hurting… but on the whole I’m showing you the sunny side of America, because that’s what I want you to see; that’s what I see and love,” says Highsmith.

“It’s a gift to be in this country. If you see my work, you will know it’s America; it’s about us, who we are and how we operate. Life can be tough, not every day is 100% perfect, but the horrible days sort of meld into wonderful days where the sun shines and flowers bloom and everything is fabulous again,” she said.

As part of Women’s History Month, Highsmith often considered “America’s Photographer,” takes us on a metaphorical journey through some of the most iconic moments of a storied 41-year career. The Prints and Photographs Division houses her life’s body of work – close to 100,000 photographs— making her the only living photographer documenting America’s milestones to have an individual namesake collection.

Self-described as a “visual documentarian” and “an architectural photographer with a twist,” Highsmith found inspiration in legendary female photographers before her, like Frances Benjamin Johnston and Dorothea Lange, whose works are also featured at the Library.

Highsmith launched her career in 1980, working for the Corcoran School of Photography on a 3-year project at The Willard Hotel, the “hotel of presidents” two blocks from the White House, which was undergoing a massive restoration. There were no architectural photos of the building’s interiors to guide crews, only those Johnston had made decades earlier. The building had since deteriorated until, Highsmith said, it looked as if it had been hit by a “nuclear blast.” Side-by-side pictures of Johnston’s and Highsmith’s sum up the hotel’s trajectory.

The Willard Hotel, in days of disrepair. Photo: Carol Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

Just as Johnston had documented some of America’s presidents, national events and landmarks, so too Highsmith pledged to become the nation’s unofficial photographer.

Tethered to her 151-megapixels digital camera, Highsmith also found inspiration in Lange, whose haunting depiction of breadlines, destitute farmers and hardscrabble migrant workers during the Great Depression left its mark in photojournalism. Lange’s “Migrant Mother,” taken in 1936, is one of the Library’s most downloaded images, and during a road trip in California, Highsmith was thrilled to find the very spot of the migrant camp where that iconic photo was taken.

Richard Ortiz, a migrant worker in Nipomo, California, at the spot where Dorothea Lange photographed migrant worker Florence Owens Thompson in 1936. Photo: Carol Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

The pandemic has made her work a lot easier in virtually deserted tourist traps, like Louisiana’s historic antebellum plantations, New Mexico chapels or Santa Fe’s plaza, that normally would be teeming with thousands of visitors. While the pandemic robbed Louisiana of the festive Mardi Gras parades, Highsmith photographed “Yardi Gras,” the beautiful artwork on people’s front lawns and porches that resembled Mardi Gras floats.

“What I’m showing you in these photographs is five months of ‘Hello, is anyone there?’” she said of her work during the pandemic. “I remember on a weekday morning at Union Station (in DC), not a soul but a policeman and his dog, can you fathom that?”

Other photographs depict, in Highsmith’s words, “poignant vestiges of simpler times,” like those she took of Iowa’s unpaved roads and tidy farmsteads in 2018. The dilapidated buildings, sagging wooden barns and abandoned grain elevators ooze a certain sadness and nostalgia for what she calls “disappearing America.”

But ever the eternal optimist and storyteller, Highsmith’s camera captured red-colored buildings and early morning sun rays that bathed the bucolic scene in a special glow. An unplanned “selfie” moment, for sure.

Recalling events that have impacted her work and perspective, Highsmith brings up memories of 9/11. She had taken photographs of the Manhattan skyline two months prior to the terrorist attacks that wiped the Twin Towers off the cityscape forever.

It’s all part of her quest for preserving a piece of history for the ages, and she’s not done yet. Her epic state-by-state study has yielded thousands of photos, and many more will pivot to people. In a field stubbornly dominated by men – female photographers face barriers in some of the world’s major newspapers, according to a 2020 study— Highsmith stands out precisely because her multi-year, multi-state study is a rare feat.

Growing up in Minneapolis, Highsmith remembers her dad photographing and documenting her young life, and she credits him for helping her find her life’s passion. Guided by a can-do attitude and a strong work ethic, this septuagenarian advises young women pursuing careers in photography and other male-dominated professions to “never, never, give up… you got to knock on 3,000 doors, somebody might say ‘yes’ at the last one.”

Highsmith has leaned on Ted Landphair, her husband of 40 years, for moral, logistical and production support. And, of course, for much-needed banter in a nomad’s life, during months-long stretches away from home in Takoma Park, Maryland, a D.C. suburb, and their four beloved cats.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 25, 2021

Kermit! On Fame, Fortune and the 2020 National Recording Registry

We get a fair number of famous people passing through your favorite national Library, but it’s not everyday that the world’s most famous (and only singing) frog hops on a video interview with the Librarian herself.

But Kermit the Frog did indeed chat with Carla Hayden about his induction into the 2020 class of the National Recording registry and his notable breakthrough of being the first frog to ever make the list. His entry was “The Rainbow Connection,” the huge hit from 1979’s “The Muppet Movie,” which made him a banjo-strumming star.

The list, announced yesterday, is an annual 25-recording addition to the nation’s historical archives of music, broadcasts or other recordings. There are now 575 recordings on the list. Highlights from this year include Janet Jackson’s “Rhythm Nation;” Louis Armstrong’s “When the Saints Go Marching In;” Phil Rizzuto’s broadcast of Roger Maris hitting his 61rst home run, breaking Babe Ruth’s single-season record; Jackson Browne’s “Late for the Sky;” Kool & the Gang’s “Celebration,” and one of Thomas Edison’s first recordings. (You can nominate songs yourself; about 900 were suggested this year.)

In the interview, Hayden asks the Muppet star about the film’s shooting, how he handles fame and the lasting meaning of “Rainbow.” There’s also a guest appearance by songwriter Paul Williams, who co-wrote the piece with Kenneth Ascher. Williams, the Oscar Award-winning writer of “Evergreen” and recipient of the Johnny Mercer Award, says the song is about “the immense power of faith.”

Kermit agreed, and was excited by his induction.

“Well, gee, it’s an amazing feeling to officially become part of our nation’s history,” he told Hayden. It’s a great honor. And I am thrilled — I am thrilled! — to be the first frog on the list!”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 24, 2021

The 2020 Class of the National Recording Registry: A New “Rhythm Nation”

Brett Zongker and Leah Knobel of the Library of Communications media relations staff contributed to this story.

It was 1989, and Janet Jackson’s “Rhythm Nation 1814” hit the eardrums and radio airwaves like a dance track for a social-justice protest. The title track, “State of the World,” “Miss You Much” and “Escapade” helped set records for Top 1o hits off a single album. Its call for social action was one of the strongest in pop music since Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On.”

That album, with most tracks written and produced by James “Jimmy Jam” Harris III and Terry Lewis, helps headline the Library’s 2020 class of the National Recording Registry. The other 24 recordings now preserved for posterity as part of the nation’s history range from rap to opera to baseball to one of Thomas Edison’s first recordings.

Janet Jackson. Press photo from “Rhythm Nation.“

“We wanted ‘Rhythm Nation’ to really communicate empowerment,” Harris said. “It was making an observation, but it was also a call to action.”

Highlights of the Class of 2o2o: Nas’ “Illmatic,” Louis Armstrong’s “When the Saints Go Marching In,” Jackson Browne’s “Late for the Sky,” Flaco Jiménez’s “Partners,” Franklin Roosevelt’s 1941 Christmas Eve radio address with Winston Churchill, Leontyne Price’s “Aida” and Kermit the Frog’s “The Rainbow Connection.” First timer: A podcast, a 2008 episode from “This American Life” about the mortgage crisis then sweeping the country.

“The National Recording Registry will preserve our history through these vibrant recordings of music and voices that have reflected our humanity and shaped our culture from the past 143 years,” said Carla Hayden, the Librarian. “We received about 900 public nominations this year for recordings to add to the registry.”

There are now 575 recordings on the registry, a tiny fraction of the Library’s 3 million sound recordings.

Flaco Jiménez. Photo: Leonard Jiménez.

The contributions come from all over the nation, parts of the Caribbean and from earliest days of recorded sound. Jiménez, for example, has been playing his south Texas music since he was a kid in the 1940s, in both English and Spanish.

He heard his grandfather and father playing it. He picked up his signature instrument, the accordion, as a boy. Over a seven-decade career, he’s recorded his “energetic happiness” with some of the most accomplished country and pop musicians of the day, including Ry Cooder, Dwight Yoakam, John Hiatt, Linda Ronstadt and Los Lobos.

“People used to regard my music as cantina music, just no respect,” he said in a recent interview. “The accordion was considered something like a party joke…I really give respect to everyone who helped me out on this record and I’m flattered by this recognition.”

Jimmy Cliff brings Jamaica into this year’s list, with his acting and singing role in “The Harder They Come,” the first film produced on the island, in 1972. The soundtrack features six songs recorded by Cliff (“Many Rivers to Cross,” the title track, “Sitting Here in Limbo,”) and has been credited with taking reggae worldwide .

Going back to the early 20th century, songs by then-recent immigrants from Europe made the list. Hjalmar Peterson, a Swedish immigrant who settled in Minnesota, became a popular entertainer, including his hit “Nikolina.” Marika Papagika, a Greek immigrant, settled in New York City and became one of the most popular singers of the Greek-American community for years.

The first frog to be featured on the list showed up this year, too. Muppet fans know Kermit the Frog’s “The Rainbow Connection” from 1979’s “The Muppet Movie.” Songwriter Paul Williams, who wrote the music and lyrics with Kenneth Ascher, said the song is about “the immense power of faith.”

“We don’t know how it works, but we believe that it does,” Williams said. “Sometimes the questions are more beautiful than the answers.”

Kermit was excited by the news: “Well, gee, it’s an amazing feeling to officially become part of our nation’s history. It’s a great honor. And I am thrilled — I am thrilled! — to be the first frog on the list!”

The new class showcases one of the earliest recordings of an American voice by Thomas Edison in 1878, just months after he had invented his recording machine. It also captures the dramatic moment in baseball when Roger Maris broke Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record, and the soap opera “The Guiding Light” as it began on radio.

NPR’s “1A” will feature several recordings in the series on “The Sounds of America,” including interviews with Hayden and artists in the weeks ahead.

Musician Branford Marsalis credits Armstrong’s recording for making a previously regional song an international one. He recalled playing “The Saints” with his brother Wynton Marsalis while growing up in New Orleans.

“As kids in the late 1960s, Wynton and I learned it when I was still playing clarinet; Wynton playing the melody, and me playing the bass notes. … It’s the first song we played together,” Branford Marsalis said. “I can’t imagine New Orleans’ culture without this song. It is an indelible part of our history.”

Connie Smith, press photo.

A new country selection for the registry adds the voice of Connie Smith, who has been called one of most underrated vocalists in country music — and who is greatly admired by her peers, including Dolly Parton.

“I never dreamed when I walked into RCA’s Studio B in Nashville on July 16, 1964, to make my first record that a song from that session called ‘Once a Day’ would become a hit,” Smith said.

Under the terms of the National Recording Preservation Act of 2000, the Librarian of Congress, with advice from the National Recording Preservation Board, selects 25 titles each year that are “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” and are at least 10 years old. You can nominate songs yourself.

The Library’s Packard Campus for Audio Visual Conservation in Culpeper, Virginia, works to ensure that the recording will be preserved. This can be either through the Library’s recorded-sound preservation program or through collaborative ventures with other archives, studios and independent producers.

The Packard Campus is a state-of-the-art facility where the nation’s library acquires, preserves and provides access to the world’s largest and most comprehensive collection of films, television programs, radio broadcasts and sound recordings.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 22, 2021

Researcher Story: Kimberly Hamlin

Kimberley Hamlin. Photo courtesy of the author.

Kimberly Hamlin is a history professor at Miami University in Ohio and a distinguished lecturer for the Organization of American Historians. She researched her latest book, “Free Thinker: Sex, Suffrage and the Extraordinary Life of Helen Hamilton Gardener,” in the Library’s Manuscript Division.

Who was Helen Hamilton Gardener?

Helen Hamilton Gardener is the most interesting and influential suffragist that no one has ever heard of. When she was 23, she was outed in Ohio newspapers for having an affair with a married man (he told her he was divorced). Rather than slink away in shame as a “fallen woman,” she moved to New York City, changed her name (she was born Alice Chenoweth) and reinvented herself.

By 1893, Gardener was one of the most sought-after speakers and writers in the country. In 1910, she moved to Washington, D.C., and joined the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Her colleagues called her their “diplomatic corps” and “the most potent factor” in congressional passage of the 19th Amendment. In 1920, President Woodrow Wilson appointed her to the U.S. Civil Service Commission, making her the highest-ranking woman in federal government and a national symbol of what it meant, finally, for women (at least white women) to be full citizens.

What inspired you to tell Gardener’s story?

wrote about Gardener’s brain donation (yes, brain donation) in my first book. She donated her brain to science when she died in 1925 to prove the intellectual equality of women, and I wanted to learn all about her.

So, I started tracing her life with support from a National Endowment for the Humanities Public Scholar Award. One day, in the Library’s Manuscript Reading Room, I came across a coded letter Gardener wrote revealing her scandalous 25-year-long relationship with Charles Smart, the man she had the affair with. I knew then that I had to tell her remarkable story. I documented her life with research at the Schlesinger Library and, especially, the Library of Congress, along with probate and military records, digitized historical newspapers and her vast writings.

Given Gardener’s influence in the suffrage movement, why is she less well known now than other prominent suffrage advocates?

Gardener is less well known for two main reasons. First, she mandated in her will that her papers be destroyed. So, telling her story was not easy or obvious. Second, much of her “diplomatic work” for the 19th Amendment took place behind closed doors with President Wilson and his top staff, with her friends in Congress and with her next-door neighbor, House Speaker “Champ” Clark.

Can you comment on your use of the Library’s collections?

“Free Thinker” draws most heavily on the Adelaide Johnson collection — I found the letter revealing Gardener’s relationship with Smart there — and the papers of Woodrow Wilson and his top staff, especially Joseph Tumulty.

I also looked at the papers of the members of Congress Gardener lobbied to see how the 19th Amendment got through the Senate after languishing just a few votes shy of passage throughout 1918 and half of 1919. Here, the most instructive sources came from the papers of Sens. John Sharp Williams of Mississippi and William Borah of Idaho. Both collections have small subject files on suffrage, but the frankest debates are documented in chronological correspondence folders from the weeks leading up to key votes in the Senate. The most eye-opening source is a letter from Williams to Gardener explaining why he would never vote to enfranchise Black women in Mississippi.

Do you have advice for other researchers on navigating the Library’s collections?

Consult the expert archivists and staff at the Library and brainstorm together! My second piece of advice — especially for those working on topics related to women, sex and gender — is to take finding aids and indexes with a grain of salt. The stories we seek to tell most certainly exist in the archive, but they may not be indexed or labeled.

What’s next for you?

My next book will be a history of the temperance movement. Temperance advocates tend to get short shrift as killjoys who wanted to shut down the party when in fact I think they were the #MeToo movement of the 19th century. I have done some preliminary research in the Library’s Mabel Walker Willebrandt collection and am excited to return when the Library reopens to the public.

Another Little Piece: A New Way to Study Medieval Manuscript Fragments

This is a guest post by Marianna Stell, a reference assistant, Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

When most of us think of Janis Joplin’s hit song “Piece of My Heart,” it’s her raspy voice that worms its way into our brains, and we start humming, “come, on, come on, take another little piece of my heart now, baby!”

Though Joplin’s version topped the charts in 1968, the song was recorded two years prior by Erma Franklin, Aretha Franklin’s older sister. Both versions express the protagonist’s experience of feeling torn apart. She is appreciated, the song goes, but not enough. Internal fragmentation results.

If medieval manuscripts in the United States had a voice beginning in the early part of the 20th century, they might have sung a similar tune. In the hands of the famous bookdealer Otto Ege, (1888-1951), they were appreciated, but not enough to be supported as whole entities. Ege was a book breaker. He called himself a “Biblioclast.”

Detail of fragment from a 1310 Bible from one of Ege’s portfolio boxes. Rare Books and Special Collections.

“For more than 25 years,” Ege explained in the March 1938 issue of the hobby journal Avocations, “I have been one of those ‘strange, eccentric, book-tearers.’” An art professor in Cleveland, Ohio, Ege purchased manuscripts, cut them up, and turned them into portfolio books, which he sold to libraries across North America. A detail from one of these, from a 1310 manuscript “Paris Bible,” is pictured at left. It’s written n Latin vulgate in a gothic script. Ege included it in a portfoloio box, “Fifty Original Leaves from Famous Bibles. ”

Ege justified his actions as being democratically motivated. He reasoned that few university libraries and collectors could afford a complete medieval manuscript. By his logic, in breaking these treasures and providing buyers with a sample of manuscript leaves from various times and places, he allowed more people to enjoy access to these fragments of history.

Ege’s argument was sincere if problematic.

Then, as now, a clear financial benefit existed to breaking a manuscript. A bookdealer makes a lot more money by selling individual leaves to different buyers than by selling an entire manuscript to a single buyer. This problem remains well-known to circumspect curators and ethical antiquarian bookdealers, who rely on well-documented provenance records in order to prove that the purchase of an item does not support the dismembering of cultural artifacts.

While no one can turn back the clock and spare these manuscripts from Ege’s destructive appreciation, a new field of digital humanities has emerged as an answer. The Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library is collaborating with the international initiative Fragmentarium.ms to help pioneer what’s called digital fragmentology.

Fragmentarium is building an international community around the ability to identify, search, compare, and collect data on medieval manuscript fragments. What does that mean? For one, it means that libraries across the world can work together to create complete virtual reconstructions of Ege’s manuscripts. One of the most famous reconstructions is the Beauvais Missal for which leaves from more than 60 locations were brought together.

Here in Rare Books, we’re in the process of bolstering our fragment identifications and descriptions so that our fragments—loose leaf fragments, those added to manuscripts or books, and those used as waste in the bindings of other books—can be discovered.

While important information is lost when a manuscript is broken apart, fragments in-and-of themselves can be quite important. During the medieval and early modern period, manuscripts deemed no longer useful were often used as structural support within book bindings. Now, some of these in situ fragments are of greater historical interest than the text block the binding was once fashioned to protect.

Fragment of Ivo of Chartre’s “Dectrtum” pasted to the back board of Leonardus de Utino’s Quadragesimale aurem Venice, Francisus Renner, 1741.

We were recently reminded of this fact when, upon opening a rather homely looking Venetian imprint we discovered a late 11th-century manuscript fragment pasted on the inside of the back board (above). Written in a late Caroline scribal hand that is not especially refined, the text of this fragment is clear enough to be identified as the work of Ivo of Chartres.

Ivo was bishop of Chartres Cathedral in Paris from 1090 until his death in 1115. His writings were foundational to the development of the late medieval legal tradition, and his influence was immediate and widespread throughout Europe.

The Library’s fragment corresponds to the section of Ivo’s Decretum—a collection of decisions and judgments in canon law—in which the bishop discusses baptism. Based on the scribal hand, the Library’s fragment likely dates to the end of the 11th century, right around the time the Decretum was being created, and toward the end of Ivo’s life.

This fragment was likely later used as binding waste because it had no aesthetic value and the text was for some reason not considered useful.

Piecing together the narratives of these fragments helps scholars reconstruct portions of history that would otherwise remain locked in vaults or portfolios. In making the fragment collection more accessible, we hope to encourage a healthy appreciation of fragments that leads to constructive conversations and discourages destructive collecting habits.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers