Library of Congress's Blog, page 44

May 28, 2021

My Job: Shannon Gorrell

Shannon Gorrell, Health Services Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

During Public Service Recognition 2021, we’re recognizing some of the unique people who make the Library special. Shannon Gorrell is senior clinical manager in the Health Services Division.

Tell us a little about your background.

I grew up mostly in San Diego but went to high school in Charlotte, North Carolina, and attended the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill, where I majored in biology and chemistry. I joined the Marine Corps after graduation and served on active duty as an intelligence officer for eight years, including a deployment in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Afterward, I returned to UNC-Chapel Hill and completed a Bachelor of Science in nursing. During that time, I was activated by the Marine Corps and deployed to Afghanistan for Operation Enduring Freedom. Upon graduation in 2007, I moved to Washington, D.C., and worked in the emergency departments of Georgetown University Hospital and Bethesda Naval Hospital.

In 2014, I earned a Master of Science in nursing from George Washington University as a family nurse practitioner and started working for Medical Faculty Associates as an urgent care and primary care nurse practitioner in downtown Washington, D.C.

I was recalled back to active duty again in 2017 and spent three years in the Pentagon developing intelligence strategy and policy for the Marine Corps.

What brought you to the Library, and what is your role?

I was excited to see the senior clinical manager job advertised — I saw it as a great opportunity to combine my leadership, policy and clinical experiences. I started in spring 2020 and supervise the clinical staff and operations of the Health Services Office under the direction of Dr. Sandra Charles, the Library’s chief medical officer.

What have you been focusing on during the pandemic?

Since I was hired in the middle of the Library’s pandemic response, I have been learning the ropes and trying to make sure we keep the Library a safe and healthy place for our employees. I am very proud of the great team we have in the Health Services Division and what we have been able to accomplish.

What do you enjoy doing outside work?

I currently command the Marine Corps Reserve detachment at the Marine Corps Intelligence Activity in Quantico, Virginia. When I am not fulfilling those responsibilities, I enjoy taking advantage of all the great indoor and outdoor activities D.C. has to offer, traveling and hanging out with my 10-year-old miniature Australian shepherd dog, Angie. Also, every year, my father and I raise money for the National Multiple Sclerosis Society by riding 100 miles in a cycling event in North Carolina.

What is something your co-workers may not know about you?

In 2010, I was selected for a congressional fellowship through the Department of Defense. I worked in the office of Sen. Dianne Feinstein on defense and veterans’ issues. It was a great opportunity to learn about Congress and the legislative branch. I was also fortunate to have access to and benefit from the great work that the Congressional Research Service does — it definitely made my job easier and more fulfilling!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

May 26, 2021

How to Research the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

Tulsa’s Greenwood District after the massacre. Photo: American Red Cross. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Wanda Whitney, Head of History & Genealogy, Researcher and Reference Services.

This week marks the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre, in which a mob of whites invaded and burned to ashes the thriving African American district of Greenwood, also known as Black Wall Street.

It was, then and now, among the bloodiest outbreaks of racist violence in U.S. history. The official tally of the dead has varied from 36 to nearly 300. White fatalities are documented at 13. Some 35 square blocks of Black-owned homes, businesses, and churches were torched; thousands of Black Tulsans were left homeless – and yet no local, state or federal agency ever pursued prosecutions. The event was so quickly dismissed by local officials that today, a century later, several local organizations are still investigating reports of mass graves.

I became interested in what happened in Tulsa when I watched the 2019 HBO series, “Watchmen,” which opens with a depiction of the massacre. I had heard about the Greenwood massacre before but didn’t know much about its history. Then late last year, a patron contacted our Ask a Librarian service with a question about racial massacres. That spurred me to investigate the Library’s collections to see what I could find out about the Tulsa massacre and similar events that occurred in the United States in the post-World War I era.

The Researcher and Reference Services Division put together a guide to conducting your own research. But first, let’s establish some context and basic facts, as the massacre occurred against the broader canvas of post-World War I racial unrest that bubbled up across the nation.

In 1919, Black soldiers, returning from the battlefields of Europe, expected that their sacrifices and service to the nation would be recognized by whites, that Jim Crow segregation and state-sponsored racism would be eased. That was not so. By and large, white society sought to enforce the segregated status quo that had existed before the war. A series of racist attacks and deadly fights ensued. It was so bloody that it became known as the “Red Summer.” You can research this era in our research guide, Racial Massacres and the Red Summer of 1919.

In Tulsa, two years later, the situation was much the same on the morning of May 30, Memorial Day, when Dick Rowland, who worked as a shoe shiner, got on an elevator in the Drexel Building in downtown Tulsa. The elevator operator was a white teenager, Sarah Page.

It has never been clear what transpired, but Page said Rowland “attempted to assault” her. Police arrested Rowland the next day, as the Tulsa Tribune ran a short story with the headline: “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in an Elevator.”

By early evening, an angry group of several hundred white Tulsans assembled outside the county courthouse where Rowland was being held. Some were intent on lynching him and tried to break in. Groups of black men, from 25 to 75 strong, many of them veterans carrying their service revolvers, came to help defend Rowland, but were ordered to leave by police.

Then, around 10 p.m., shots were fired in the crowd. Chaos and mass violence broke out, spreading far from the courthouse. The Black groups were quickly outnumbered and outgunned, in part because local officials provided weapons to white men whom they “deputized.” Black residents retreated into their Greenwood neighborhood, but it was no protection. Thousands of white people rushed into the neighborhood at dawn the next morning, looting, burning and killing. Mount Zion Baptist Church billowed smoke and flames. The Dreamland Theater was destroyed. The neighborhood was reduced to rubble.

It was over by noon.

Black citizens being held at the local fairgrounds. Photo: American Red Cross. Prints and Photographs Division.

Thousands of the Black survivors were forced into the city’s fairgrounds, released in the coming days only if a white person vouched for them.

Despite this shocking violence, no city, state, or federal criminal prosecution was ever mounted. The narrative was minimized or scarcely mentioned in public discourse and history books for nearly 50 years. As a commission appointed by the Oklahoma legislature reported nearly eight decades later: “There had been a pattern of deliberate distortion of facts regarding the riot and even the destruction of vital documents and a subsequent coverup.”

This was a sobering record to confront. I suspected that finding information about the Tulsa massacre might not be an easy task. While there were differing newspaper reports and oral histories published at the time of the event, there still remained a dearth of official primary sources or official records to bear witness to what happened. And although we now refer to the event as a “racial massacre,” it was called a “race riot” for many years.

The Library has already begun retitling this event as a “massacre” in our catalog descriptions. Please note, however, that we do not change descriptions of any events in our collection items themselves, such as newspaper accounts or other records contemporaneous with the massacre.

So, to begin your research in our collections, use the keywords, “Tulsa race riot” in the search field on our homepage. For photos, you can filter your initial results to the Photos, Prints, Drawings category. Most of the images come from the NAACP records or the American National Red Cross photograph collection.

You can get a block-by-block look at Tulsa and the Greenwood district in that era with our Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of the city in 1915.

The Greenwood Business District was bordered by Archer Street at bottom, Detroit Avenue at left and railroad tracks at right. Greenwood Avenue is in the middle of the map, going north to south. Almost all of this area was burned. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map. Geography and Maps Division.

Various newspapers, both local and national, reported the event. You can search our Chronicling America collection for articles about the massacre. For helpful search tips, check out our research guide, Tulsa Race Massacre: Topics in Chronicling America.

The Tulsa World, Thursday, June 2, 1921. Chronicling America.

The public’s renewed interest in the massacre began with publications about it in the 1970s and 1980s and culminated in the 1997 establishment of The Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, mentioned above. This legislative Commission put out a national call for survivors who could give interviews for oral histories. It also worked with historians who gathered information about what happened. Their report, published in 2001, became part of the official history. The Library has a print copy of the report. For additional books in our collection, take a look at the print bibliography in the Racial Massacres research guide. There are many books devoted to the massacre, including “Tulsa 1921,” “The Burning,” and “Death in a Promised Land.”

For eyewitness accounts, the Library has oral histories of 3 survivors of the massacre interviewed by Camille O. Cosby for the National Visionary Leadership Project. Other accounts appear in the HistoryMakers database, a subscription database available onsite at the Library. They are fascinating to watch. If you can’t come to the Library, see what your local public library may have on the Tulsa massacre. Other sources of oral interviews, documents, and photos include the Oklahoma Historical Society, Tulsa Historical Society & Museum, and the electronic library, Oklahoma Digital Prairie, among others.

The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, created in 2015, continues the work of the Oklahoma Commission to tell the history of Greenwood. Look for events in May and June that coincide with the 100th anniversary of the event.

Finally, one note of irony. Rowland, the original target of the violence, was neither harmed nor charged with any wrongdoing. He left town and the rest of his life could not be traced, the Tulsa World reported last year. “Dick Rowland,” the name he gave to police, may not have even been his real one, the newspaper reported. Page, the teenaged elevator operator, had only recently arrived in the city and left soon thereafter, the paper said, and could not be tracked down, either.

I wish you success with your research into this troubling episode in our history. If you have a more specific research request, or need assistance searching for resources, please use our Ask a Librarian service.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

May 24, 2021

Roman Totenberg: A Symphony of a Life

Roman Totenberg, 1936, at his U.S. debut. Music Division.

Roman Totenberg was born in Poland in 1911 and died in the United States in 2012, a 101-year odyssey that was more an era than a lifespan.

His papers at the Library tell the story: A child prodigy on the violin who played on Moscow street corners to help his family survive famine after the Bolshevik Revolution, he later fled the Holocaust to become a virtuoso who played in the world’s greatest concert halls, alongside the century’s greatest composers and on hundreds of recordings.

He won major European music prizes, played for the Italian king, toured with legendary pianist Arthur Rubinstein and dined with President Roosevelt by the time he was 25. When he was 70, he was named the Artist Teacher of the Year by the American String Teachers Association. At 85, Boston University, his longtime teaching home, named him as the university’s top professor.

In his last days, former students — many of whom had been toddlers when he was old enough to retire — came to play for the maestro one last time. He beckoned to one after a bedside performance. Barely able to whisper, he said, “The D was flat.”

“He was a tender soul,” said Nina Totenberg, his daughter and NPR’s legal affairs correspondent, in a recent interview, “and a lot of fun.”

The Totenberg family: (clockwise, from upper left) Melanie, Nina, Roman, Jill, Amy. Music Division.

The collection of his papers forms a vibrant testament to the intensity, brilliance and creativity of one of the 20th century’s greatest violinists, given particular relevance during Jewish American Heritage Month.

His cosmopolitan story unfolds in family photographs, postcards, letters (including from Albert Einstein and Leonard Bernstein), handwritten notations on his sheet music, and dozens of his recordings. There are also surprises, such as the sketches, woodcuts and paintings of Ilka Kolsky, a close friend in pre-war Paris.

Amy Totenberg, another daughter and a senior U.S. District Court Judge in the Northern District of Georgia, said that their childhood in the artistic household was “normal, but charged with a great sense of my father’s musical world and adventurous life that swept us up too. Our parents’ loving embrace of life was infectious.”

A promotional poster. Music Division.

Roman Totenberg’s remarkable life began in Lodz, a small city in what is now Poland. But in 1914, during World War I, the family had to flee a German invasion of the territory, moving to Warsaw. His father, Adam, was an engineer and architect, soon moved the family to Moscow to work on railroads and hospital projects.

As it happened, the Totenbergs moved in next door to the concertmaster of the Bolshoi Orchestra. The man took an interest in young Roman, sometimes serving as his babysitter, and was amazed by the boy’s proficiency on the violin. Roman, it became evident, had perfect pitch. After the Bolshevik Revolution, when the nation fell into starvation-level poverty and the borders were closed, he began playing on street corners, bringing home bread, butter and sugar. It was more than his father could provide, he said in later interviews.

Still, when he would march out on stage for larger shows, introduced as “Comrade Totenberg,” the audience laughed, he told interviewer Leon Botstein, president of Bard College.

“They … expected a big person,” he said, “so I was terribly offended and that’s my first memory of performing.”

The days were bleak. The family was so desperate for food that when a lame horse was put down, the whole neighborhood cut it up for food. The Totenberg family got the head. The young boy would always remember his mother knocking out the eyes before cooking it.

The family was finally able to return in May 1921 to Warsaw, capital of a newly independent Poland. Roman became a child star, making his debut with the Warsaw Philharmonic at 11. He moved to Germany while still a teen in order to study and perform. But in 1932, when he was 21, Hitler’s rise and the wave of antisemitism made it impossible to stay. “I saw that it was really coming; the SS beat up some colleagues and friends,” he told Botstein.

He lived and studied in Paris, returning briefly to Warsaw in 1935 after the death of his father, bringing his mother back with him. He was soon touring with Rubinstein (also a native of Lodz) in South America. He made his American debut late that year with the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, a performance that drew six encores and an invitation to the White House.

He returned to the U.S. to stay in 1938. With World War II imminent, he got his mother, Stanislawa, on one of the last ships out of Portugal and brought her safely to the U.S.

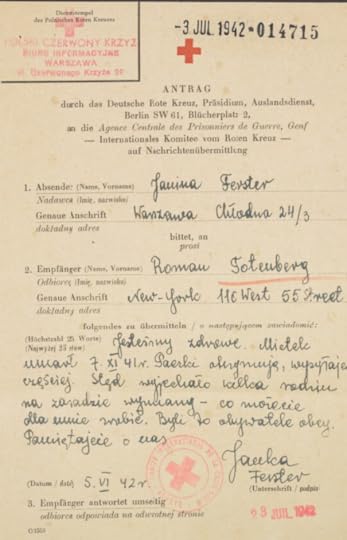

The war years were pure anguish. His papers show the efforts he put into trying to get family, friends and relatives away from the Nazi death camps. His sister, Janina Ferster, her husband and child were trapped in Warsaw. He was able to get money to them, his papers attest, but he could not find a way to help them escape.

The Nazi regime sent the family to the Warsaw Ghetto, where Jews were held in an atmosphere of “fear, menace and terror,” his niece, Elizabeth, then a young child, later remembered at the 2016 Righteous Among Nations Awards ceremony.

Totenberg’s brother-in-law, Mieczyslaw, died in the ghetto on July 11, 1941, likely of typhoid fever. It was nearly a year before Ferster managed to send Totenberg a Red Cross postcard. Limited to telegram-like shorthand, using her husband’s nickname, the entire note reads:

“We are healthy. Mietek died 7/XI/41. The package I received. Send them more often. From here a few families left on the principle of exchange — What can you do for me. They were foreign citizens. Remember us.”

Janina Ferster’s letter from the Warsaw Ghetto.

He did. And his name was so revered in Poland that when a local musician learned that his sister was trapped in the ghetto, he helped create false papers t o get her and her daughter out. Ferster and Elizabeth survived the rest of the war in Warsaw, moving from place to place, always a step ahead of the gestapo. After the war, Elizabeth lived with the Totenbergs, eventually settling in the United States.

Despite the agony and loss associated with the Holocaust and the war, Totenberg went on to establish a brilliant career as a performer and teacher, winning major prizes for both and becoming an international star. He worked with composers such as Bernstein, Samuel Barber, Igor Stravinsky and Aaron Copland.

He performed with most of the world’s major orchestras and appeared on hundreds of recordings. He bought the Ames Stradivarius violin and performed with it for decades, until it was stolen from his office in 1980. It was recovered after his death — a young musician had taken it — and returned to the family by the FBI.

His wife, Melanie, was also his secretary, part-time promoter and served as an extra set of ears at recording sessions. They raised three daughters, all of whom went on to successful careers (Jill Totenberg is the chief executive officer of a corporate communications firm in New York). The household was lively, but he demanded manners at the dinner table. He worked and performed into his 90s — even jumping on a grandchild’s bicycle at that age to show her how to ride it – and taught until the day he died.

“He was so engaged in all that he did and the world at large,” Amy Totenberg said. “He was a man of endless talent, love, brilliance, charm, and humanity.”

Totenberg, with his beloved Stradivarius violin, in 1947. Family photo. Music Division.

Subscribe to the blog — it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

May 21, 2021

Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month: The Rock Springs Massacre

Chinese miners in Tuolumne County, California, 1866. Photo: Lawrence & Houseworth. Prints and Photographs Division.

The fight began in a coal mine on the morning of Sept. 2, 1885, in Rock Springs, a rough-hewn village in the Wyoming Territory that lay along the Union Pacific Railroad.

White and Chinese miners, already at odds about wages, argued about who was going to work a rich vein of coal. A Chinese worker was killed in the ensuing fight, setting off the Rock Springs Massacre. That afternoon, a mob of at least 100 white men and women carrying rifles, shotguns, pistols, axes and knives surrounded and then rampaged through the Chinese neighborhood, killing 28, wounding dozens more, burning some 70 wooden houses to the ground and expelling all 500 or so Chinese residents.

“…nothing but heaps of smoking ruins marks the spot where China Town once stood,” the Las Vegas Gazette reported two days later. The newspaper noted that there were no Chinese in Rock Springs “except the dead and wounded.” Twenty-two white men were arrested, but none were prosecuted. The U.S. government eventually paid the Chinese government $147,000 in damages.

The Rock Springs Massacre is not a moment that rings out in the national narrative, as much of the violence directed at Asian immigrants in the 19th century is not widely remembered. But the rampage was the culmination of years of white workers’ resentment of Chinese laborers in the West and one of the deadliest. As Jean Pfaelzer writes in “Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans,” there were dozens of such incidents: “…thousands of Chinese people who were violently herded onto railroad cars, steamers or logging rafts, marched out of town or killed” across the region in the second half of the 19th century.

As Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month comes to a close, the Library’s collections show that understanding our complete national story means understanding that Asians in the frontier territories were frequent targets of white violence, despite their invaluable work on railroads, in mines and other industries. The Old West was burnished into a gauzy myth by Hollywood cowboy movies and country songs in the early 20th century, but the reality was far less romantic and much more brutal.

Illustration of Rock Springs Massacre in Harper’s Weekly, Sept. 26, 1885. Artist: Thur de Thulstrup. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Library’s collections document the issue, including Chinese immigration to the U.S. and the resulting waves of bigotry. There are Research Guides to building of the Transcontinental Railroad, which depended heavily on Chinese workers; the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882; the Rock Springs attack; and years of newspaper and magazine articles in Chronicling America.

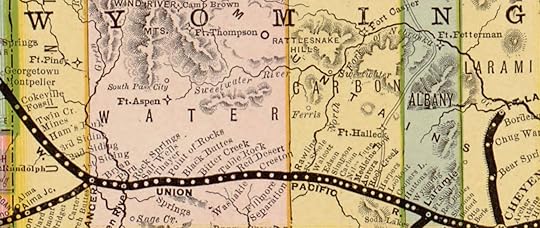

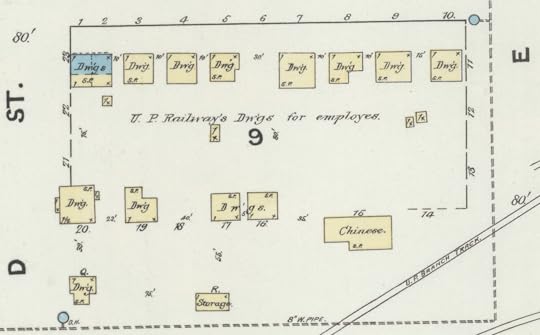

But there is more to flesh out the narrative. Maps and photographs of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads show settlements exploded across the region in the years after the nation was united by rail and the passage of the Homestead Act. And there’s a Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of Rock Springs that shows what the town – population, 2,900 — looked like, street by street, in 1890.

This 1883 map shows how towns in Wyoming sprung up along the Union Pacific Railroad. Rock Springs is the fifth stop before the railroad forks. Rand McNally and Company. Geography and Map Division.

Together, they piece together the story.

The California Gold Rush in the late 1840s drew some 25,000 Chinese workers, almost all men, to the state by 1851. Others followed. But the riches were largely an illusion, and the men, now stranded without the wealth they’d hoped to accrue and send back home, began to work in a number of hard-labor trades, often accepting lower wages than whites. This led to anger, resentment and attacks from whites.

In 1850 and 1862, California passed laws that charged Chinese miners and workers an extra tax. Also in 1862, Congress passed a law prohibiting Americans from bringing any more Chinese workers to the country, using a slur for Chinese workers in the official title. Conviction meant the ship’s forfeiture for the owner, and up to a year in prison and a $2,000 fine for anyone involved.

That didn’t mean the U.S. didn’t need the Chinese laborers’ work, though.

When Congress passed the Pacific Railway Act, also in 1862, it set into play the logistics for building the Transcontinental Railroad. Much of the dangerous work soon fell to thousands of Chinese workers. They labored on mountainsides, in gullies and ravines, with explosives and steel. Hundreds died. “On the Central Pacific Railroad alone, more than 10,000 Chinese workers blasted tunnels, built roadbeds, and laid hundreds of miles of track, often in freezing cold or searing heat,” the Library’s essay on the subject notes.

After the Golden Spike was driven in Promontory Summit, Utah, in 1869, Chinese workers were no longer so necessary to the national cause. They turned to working in mines and resentments grew. This culminated in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which prevented Chinese citizens from immigrating to the U.S. for an initial 10 years, but stayed in effect until 1943.

Such was the anti-Chinese mood in September of 1885 in Rock Springs.

The town, a collection of wood-frame businesses and houses, was centered around the mine and the railroad. A few hundred Chinese workers bunked together, mostly in houses provided by Union Pacific. White miners, organized by the Knights of Labor, wanted to strike for higher wages. The railroad was happy to use Chinese laborers but pay them less. The Chinese miners, in a far more vulnerable position than their white counterparts, had little interest in striking.

So, when the fight started in mine No. 6 that morning, white miners saw it as an opportunity to get rid of the group that was undercutting their demands. The mob assembled quickly, newspaper accounts reported. They surrounded the small Chinese district, giving the men an hour to get out, but descended on them beforehand, newspapers reported, setting fire to houses as they went. The Chinese fled, “without offering resistance,” but were shot at as they ran for hills about a mile outside of town. Others, who tried to hide in their houses, burned to death.

The attack made national news and was almost universally condemned. Some Chinese workers were brought back to the mine by the railroad company – mostly against their will – but the community dwindled. By 1890, Union Pacific designated only one building in Rock Springs to house Chinese workers, down from 50 at the time of the massacre, according to the Sanborn map.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of workers’ housing in Rock Springs, Wyoming, 1890. Chinese quarters at bottom right. Geography and Map Division.

Today, a small museum in nearby Evanston documents the history of the Chinese miners in the region, but most had departed the region by the 1930s. The U.S. Census Report for 2019 shows that only 1.1 percent of Wyoming’s population is Asian (of any national background). In Rock Springs, the Asian population is 0.6 percent, or about 260 people.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

My Job: Maurice Carter

Maurice Carter.

Maurice Carter is a head of the receiving and warehousing unit in the Logistics Services Division of Integrated Support Services. He’s kept the Library’s shipping docks open during the COVID pandemic.

Tell us a little about your background.

I was born in a small town called Lottsburg, Virginia, and attended Northumberland High School. Before coming to the Library in 1992, I worked for a freight company called Roadway Express. A relative was working at the Library, and he always talked about how great it was to work here. So, I applied for a warehouse position and got the job.

Describe a typical day.

A typical day begins with a safety briefing for staff. After that, my team lead and I review FAME — the Library’s integrated facility-management system — to see what jobs we are going to complete for the day. Staff enter requests into FAME for tasks such as removing excess computers or furniture, replacing carpets and delivering recycling and moving bins. We also help with relocating staff; moving copyright materials to off-site storage; and transporting books, newspapers and supplies from the loading dock to the Jefferson and Adams building and different divisions.

Our loading dock and transport staff carry out all duties on the dock, such as preparing recycle material for pickup by an outside vendor.

Some of the requests we receive require staff to use materials-handling equipment to transport materials or read blueprints — for carpet installation and relocation of staff, for example. Staff also use special equipment to remove furniture and computers and send them to our Cabin Branch facility for storage or disposal.

Once we decide on what jobs need to be done, we distribute work to different staff members for completion.

How has your work changed during the pandemic?

I worked in the Madison Building with a small crew from early on in the pandemic to keep the loading dock open, starting during the period of maximum telework.

Otherwise, work in my division has slowed down somewhat, as fewer FAME requests are being put into the system now. Many staff from other divisions are teleworking, so there are not a whole lot of people on-site to put in FAME requests.

What accomplishments are you most proud of?

I have several accomplishments that I am proud of from my 28 years of work at the Library. But my proudest is helping to transport the 1507 Waldseemüller world map from the Madison Building’s loading dock to the Jefferson Building for display in the Great Hall. This transport included using seven U.S. Capitol Hill Police officers for escort and a 22-foot truck. Then, we had to have five staff members walk the map up the flight of stairs in the front of the Jefferson Building. Once we got the map upstairs, we had to uncrate it and place it in a display case in the Great Hall, where it now resides.

What do you enjoy doing outside work?

I like being with family, watching my kids play basketball and riding my Harley Davidson motorcycle.

What is something your co-workers may not know about you?

In 2002, I sang the national anthem at Madison Square Garden in New York City for the National Invitation Tournament. Over 20,000 people were present to see this championship basketball game.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

May 20, 2021

“Transforming the World” — The Magic of Making Books

Russell Maret. Photo: Annie Schlechter.

This is a guest post by Russell Maret, a book artist, type designer and private-press printer working in New York City. It first appeared in the Library of Congress Magazine.

Two of the earliest-known pieces of European printing made with moveable metal type are an indulgence — a promissory note granting its holder a shorter stay in purgatory in exchange for a small fee — and the Gutenberg Bible, widely considered one of the most beautiful books ever printed. (The Library’s copy is one of three perfect vellum copies known to exist.)

These two objects describe the outer limits of what we now call the book arts, an amorphous field populated by printers, papermakers, type designers, engravers and bookbinders; craftspeople who spend their lives reckoning with their materials, trying to find some middle ground between Gutenberg’s lofty heights and the more ephemeral objects of commerce.

Like any creative field, each branch of the book arts is characterized by a kind of alchemical awe, that out of these base materials of paper, lead and ink we can make something that is greater than the sum of its parts. To print is literally to transform a blank piece of paper into a messenger of ideas, and it is a permanent transformation.

That last bit is one of the trickier aspects of printing to navigate — its permanence. It is why we are so careful about committing thoughts to paper, and why opponents of ideas are so determined to prevent their being printed or distributed (The Tyndale Bible, “Ulysses,” etc). But even permanence is relative, in as much as the permanence of an idea is subject to the shifting interpretations of time (The earth is the center of the universe!). And books, as we all know, can be burned.

In my experience, the transformational power of print is not only technical, it is existential. In 1989, I inked up a printing press and pulled a proof for the first time. I was 18 years old, and in that instant I changed from a dreamy kid who had never worked with his hands into a determined apprentice. Printing was literally the first thing I ever wanted to do and now, over 30 years later, I am still determined to do it better.

Then, in 1996 I had a sudden vision for the design of a typeface, having never studied type design or calligraphy before. Since then type design and alphabetical form have become the primary focus of my work. The books that I make likewise feed from and into each other, changing the way I think of the work I made 10 years or 10 days ago. They map new pathways for me to pursue in my books and, in the process, they change my understanding of myself.

Making a book is not an easy task. It involves hard physical work, a high level of attentiveness and, ideally, a willingness to reevaluate and change. It is a pursuit that is simultaneously primed with the excitement of permanence and transformation while being undercut with the melancholic knowledge that one’s efforts might fall short of both.

I have made some books that have come close to communicating what I wanted to say. I have made others that I would prefer not to see distributed, and I have made a few books that I would not mind burning. But when I was making each of them, no one could have persuaded me that I was doing anything short of transforming the world.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

May 17, 2021

Herencia, the Library’s Spanish-Language Crowdsourcing Project, Has Banner First Year

One of the documents being transcribed in the Herencia project.

This is a guest post by Geraldine Davila Gonzalez.

The debut of the Library’s first Spanish-language crowdsourcing campaign seemed ill-fated at first. Just days before the launch of “Herencia: Centuries of Spanish Legal Documents” last spring, the Library closed due to COVID-19.

But the staff quickly pivoted to a virtual opening, holding an online transcribe-a-thon. Then they added other outreach initiatives, including a remote internship program. Now, a little more than a year after its launch, more than 800 volunteers have transcribed more than 3,000 pages.

“The pandemic disrupted our plans to host Herencia transcription and review events on-site,” said Robert Brammer, chief of the Law Library’s Office of External Relations. “As it turns out, we have been able to host more events virtually and invite people across the world to participate.”

Herencia is a collaboration between the Law Library; the Hispanic Reading Room; the African, Latin American and Western European Division; and the Library’s inaugural crowdsourcing transcription team, By the People. It focuses on a collection of Spanish legal documents in Spanish, Latin and Catalan dating from the 15th to the 19th centuries. By making the documents more searchable and accessible online, the campaign aims to open the legal, religious and personal histories of Spain and its colonies to greater discovery.

Herencia, which translates roughly to “heritage” or “inheritance,” operates the same way By the People does and uses the same platform. Volunteers transcribe historical documents word-for-word or peer-review transcribed documents. Completed transcriptions are then put online, making them searchable by keyword.

The Law Library acquired the Spanish Legal Documents collection in 1941. Most of documents relate to disputes about inheritance and titles of nobility, taxes and privileges of the Catholic Church. Items of special interest include rare print and manuscript documents pertaining to the Spanish Inquisition, opinions of legal scholars of the Church, decisions rendered by the king’s court and other decrees by Spanish kings and government officials.

In the early 1980s, the Library got funding to organize, index and microfilm the collection. Digitization began in 2017.

Herencia was selected for crowdsourcing because of its value as a collection and its appeal to historically minded volunteers. Still, the pool of potential volunteers is smaller than for big-picture By the People projects, even though volunteers don’t have to speak Spanish to participate.

To build participation, the Law Library introduced a remote Herencia internship in January. Interns are transcribing documents and reviewing transcriptions, helping to identify names, places and dates missing from existing descriptions and researching secondary sources that provide context about documents. They are also inviting new volunteers.

Among this spring’s seven interns are a first-generation Mexican American undergraduate at Texas A&M International University who seeks to learn more about Spanish history and culture; a first-year student at Claremont McKenna College who wants to put her knowledge of Latin to use; a librarian born and raised in Lima, Peru; and a historian specializing in Latin America who is pursuing a master’s in library and information science.

“The Law Library is fortunate to be able to host such a talented group of multilingual interns who can perform original research and help us share Herencia with a broader audience,” said Jay Sweany, chief of the library’s Digital Resources Division.

To celebrate the first anniversary of Herencia, the Law Library hosted a review challenge in March in which volunteers peer-reviewed 159 transcriptions in four days. A similar project last July took 10 days to complete 140 transcription — showing that the nascent project had doubled its pace in less than a year.

The Library also hosted an online conversation with interns in a “lunch and learn” webinar series to mark the anniversary. The panel explored the interns’ experiences and favorite discoveries,

We’re delighted to say that Herencia is now accepting applications for summer internships.

“It’s hard to believe that this campaign started over a year ago and that we now have thousands of fully transcribed pages that will become part of the Library’s permanent collection,” Sweany said. “We are grateful for the work of our volunteers, our interns and our staff for making this possible.”

Now that the Law Library has a full year of experience with a crowdsourcing project, it’s time launch another. In honor of Law Day 2021, the Law Library and By the People will release “Historical Legal Reports” from the Law Library. Look for an announcement next week on In Custodia Legis, the Law Library’s blog!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

May 13, 2021

Not Gutenberg’s Book: Wild Innovations in Handcrafted and Art Books

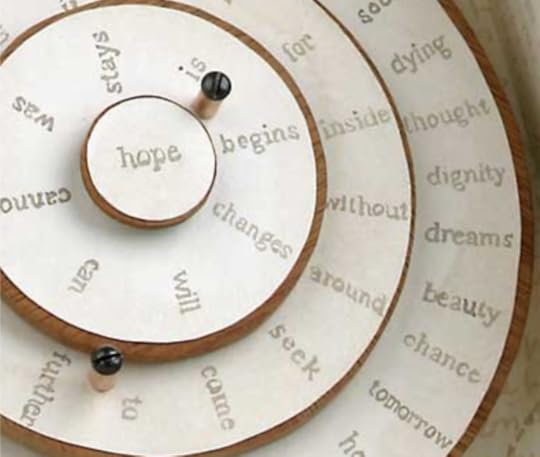

“Random Thoughts on Hope,” Laura Davidson. The wheel creates a poem each time each wheel is spun. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

This is a guest post by Mark Dimunation, chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. It appeared in slightly different form in the Library of Congress Magazine.

When William Morris produced his Kelmscott Chaucer in 1896, he did more than create a monument to his notion of the handcrafted book — he launched the revival of letterpress printing in England and America. More than a century later, that impulse has emerged as its own art form.

Books printed on the handpress using hand-set type, fine paper, woodcut and engraved illustrations and hand-sewn bindings have been the mainstay of the fine press movement. Over the years, they have transformed from their origins as an elegant and restrained homage to quality and the craft to wildly innovative and expressive print objects that celebrate the blending of text, type and image into a singular artistic vision.

Because this movement in many ways continues the story first told by Gutenberg and the introduction of the printed book, the Rare Book and Special Collections Division collects exemplars of the fine press movement. The foundation of the Library’s holdings of book arts is built on the narrative thread of the story of letterpress printing. With 500 years of the history of the printed book preceding the Fine Press Collection, it is, in effect, the extension of the rare book collection into the contemporary realm of the fine press book.

“Four Gospels,” Eric Gill. Golden Cockerel Press, 1931. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

An extremely strong book arts collection has been built over the years — one that is highly representative of the field and, in many cases, comprehensive. Thousands of titles plot the chronology of the modern letterpress tradition, beginning with a comprehensive collection of the Kelmscott Press, then moving through the decades of presswork from the early English movement to the American fine presses, from the California printers to the present.

Many printers and printmakers are represented by complete and comprehensive holdings, such as those by artist Leonard Baskin and his Gehenna Press, printmaker and printer Claire Van Vliet and her Janus Press, Steve Clay’s Granary Books, the publications produced by the Women’s Studio Workshop, and many others representing the work of printers such as Ken Campbell, Peter Rutledge Koch, Carolee Campbell and Julie Chen.

But the division also holds in other collections large gatherings of materials that sit at the fringe of our consideration — shaped books, graphic novels, pop-up books, miniatures. All in all, the Library has a vast collection of the modern fine press tradition and one of the earliest established efforts in collecting artists’ books.

The books tell the story of how contemporary book arts have transformed over time. Leaving behind the elaborately designed pages of the arts and crafts movement, letterpress printers in America and England turned their attention to the simply crafted, beautifully printed book. New movements brought with them a new visualization of the page — new type, new layout design, new materials, new visions of traditional texts. Those that were to follow closely after Morris brought their own viewpoints forward. In its English Bible (1905), the Doves Press countered with a spare, unmanipulated space with a straightforward typographic sensibility.

In the decades that followed, the Grabhorn Press, the Ward Ritchie Press, John Henry Nash, William Everson and Adrian Wilson at the Press at Tuscany Alley, all experimented with the printed page and the relationship between words and illustrations. English book illustrator and typographer Eric Gill, for example, was uniquely innovative in combining typography and the figurative arts. For the “Four Gospels,” Gill designed both the typeface and the wood-engraved initials.

Beginning in the 1960s, book artists reconsidered the entire notion of the book. Artists’ books arrived on the scene, breaking all boundaries in terms of format, content and production. They issued the challenge, demanding to be placed in juxtaposition with more traditional book arts and redefining the notion of the book as a material object. Some arrived at wholly new ideas of a book. Koch created a book with lead pages, Chen produced books that could be manipulated and reshaped and Laura Davidson made unique book objects that paired her exquisite handwork with the book format. In “Random Thoughts on Hope” (2003), Davidson offers a poem that changes randomly as wheels of words are spun to fashion another line of poetry.

These collections are bolstered by archival collections in the book arts that provide significant opportunities for research. The division holds the archives of two of the greatest American book designers of the first half of the 20th century: Frederic Goudy and Bruce Rogers. Goudy commands a special place in American book arts. In addition to his work as a printer, book designer and writer, he was the first American to make the designing of type a separate profession. Rogers, a typographer and type designer, is known for his classical style, his own design of the Centaur typeface and the production of the Oxford Lectern Bible.

Recent additions include the papers of the artist cooperative Booklyn, the archives and publications of innovative printer and designer Walter Hamady and his Perishable Press, and the papers and a comprehensive collection of the work of typographer and printer Russell Maret, whose recent work has redefined the relationship between the letterform and the illustration.

“Interstices & Intersections or, An Autodidact Comprehends a Cube.Thirteen Euclidean Propositions.” Russell Maret, 2014. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Finally, printmaking is documented directly in the division’s Artists’ Books Collection, which includes examples of illustrations from the traditional livre d’artiste to the dynamic experiments of futurism. Today, this collection is the repository for hundreds of contemporary artists’ books, highlighting collaborative ventures between artist, printer and binder that characterize the postmodern book.

Artists’ books challenge the notion of a book. New materials, new processes, new formats and new approaches to content are highlighted in these contemporary efforts, and they make up an important part of the story of the book told at the Library.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

May 12, 2021

Library Preservation: Making Models of Ancient Books

A book model under construction. Photo: Shawn Miller.

This article first appeared in the Library of Congress Magazine.

Inside every historical book is a hidden story, one that reveals how the object itself was made.

Conservators at the Library study the construction of ancient volumes in order to learn more about their inner structure and how to better preserve them for future generations.

One way they do so is by building models that let them “see inside” a book’s covers to its invisible or hidden structural components — the board attachments, endbands, fastenings and sewing that hold a book together and allow it to withstand centuries of use.

Detail of a book model. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Books from different regions and eras have unique methods of construction and are built from place-specific materials: A book made in England in the 1400s was not made in the same way as one crafted in Armenia even during the same time period. The textblock and endbands were sewn in distinctive and completely different ways, as well as the board attachment and the decoration.

The models help conservators identify construction methods and materials specific to regions and to identify damage that has been caused over time by use, such as how the boards have become loose or detached, or the sewing or sewing supports have weakened or broken. Then, armed with a better understanding, conservators can chart the best course for treatment.

Tamara Ohanyan of the Library’s Conservation Division has built models of works both from Library collections and those of other institutions: Armenian, Byzantine, European, Persian and Ethiopian bindings as well as bindings of the Nag Hammadi library, a cache of leather-bound, Gnostic Christian texts from the fourth-century that were discovered buried in a sealed jar in Egypt in 1945. You can watch her creating a traditional Armenian endband, step by step, as part of her work. It’s a master class in the art of book preservation.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

May 10, 2021

New! Joy Harjo’s “Living Nations”

Joy Harjo. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Delighted to write this piece with Brett Zongker, chief of media relations.

When Joy Harjo became the 23rd U.S. Poet Laureate, she knew she wanted to take the country back to its beginnings, long before whites arrived from Europe.

Harjo, a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, wanted to document and amplify the voices of her fellow Native Americans who see the land through a different lens, different languages and a different sensibility.

“As the first Native Nations poet laureate, I was aware that indigenous peoples of our country are often invisible or are not seen as human,” Harjo writes in the introduction to her new anthology of poems from Native poets. “You will rarely find us in the cultural storytelling of America, and we are nearly nonexistent in the American book of poetry.”

Her new book, “Living Nations, Living Words: An Anthology of First Peoples Poetry” ($15, available at the Library’s bookshop) is edited by Harjo and closely tracks the work she’s undertaken as poet laureate to bring Native poets into mainstream recognition. It’s published by the Library in association with W.W. Norton & Company.

Her signature project at the Library has been to create a digital map of “First People’s Poetry.” It gathers the work of 47 contemporary Native poets into a multi-media telling of their lives and work, ranging from New York to the Hawaiian islands. The project also includes a new online audio collection developed by Harjo and housed in the Library’s American Folklife Center, which features poets reading and discussing their work.

The new anthology is a companion volume to that project, featuring poets including Natalie Diaz, Ray Young Bear, Craig Santos Perez, Sherwin Bitsui and Layli Long Soldier. The poems, chosen by the poets themselves, reflect on the themes of place and displacement with focal points of visibility, persistence, resistance and acknowledgment. It moves from east to west, from the “Becoming” of the morning sun, to the “North-South” of the central heartlands, and finishes in the West, or “Departure.”

In “Daybreak,” the first poem, Jake Skeets, a Navajo poet and winner of a 2020 Whiting Award, mixes the ancient past with the clanging modern present, writing, in part:

above a passing plane or marsh hawk or maybe a crow

casts its wing on the sweet yellow clover and field weed

on the rubble of rust tin can and car axle and wheel barrow

a basketball backboard crafted from sheet metal and

piping

The poems in the following 222 pages showcase “that heritage is a living thing, and there can be no heritage without land and the relationships that outline our kinship,” Harjo writes.

Championing this kind of work has shaped Harjo’s lifelong trajectory. Born (and still based) in Tulsa, Oklahoma — the place where the Trail of Tears ended — she earned her undergraduate degree at the University of New Mexico and an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

Her subsequent career has centered around poetry, music (she’s a saxophonist), teaching and social justice issues She’s the author of nine poetry collections, most recently “An American Sunrise.” Her memoir, “Crazy Brave,” won the PEN USA Literary Award for Creative Nonfiction. She’s won the Wallace Stevens Award from the Academy of American Poets, the William Carlos Williams Award from the Poetry Society of America and the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize.

First named as U.S. Poet Laureate in 2019, she was recently appointed to a third term — only the second poet to do so since the position was established in 1943.

And, while her focus is often on the past, her point is always about the present.

“The mapmaking represented by this anthology comes at a crucial time in history,” Harjo writes, near the end of her introductory essay, “a time in which the failures to acknowledge, listen to, and consider everyone when making the map of American memory has brought us to a reckoning.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers