Library of Congress's Blog, page 49

January 21, 2021

Congratulations to Amanda Gorman!

Amanda Gorman, delivering her poem at the inauguration. Photo: Architect of the Capitol.

This year’s presidential inauguration ceremony had so many connections to the Library, but I would like to highlight one in particular: the recitation of the Inaugural Poem, “The Hill We Climb,” by Amanda Gorman.

In 2017, I met Amanda when she read one of her poems at a Library event. Our Poetry Office staff had suggested Amanda read a poem to kick things off that night. She was the first National Youth Poet Laureate, a program run by Urban Word NYC as an extension of their city and regional poets laureate. Even then, she was a sensation.

The night of the reading, I saw first-hand her power, passion and intensity as she recited her poem, “In This Place (An American Lyric).” And I wasn’t the only one — Dr. Jill Biden saw it too. It led her to ask Amanda to serve as the youngest-ever Inaugural Poet.

I would like to congratulate Amanda on another amazing performance and say how delighted I am that her appearance on the Coolidge Auditorium stage in 2017 led her to the U.S. Capitol yesterday.

Joy Harjo, the U.S. Poet Laureate, soon to start her third term. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Let me also take this opportunity to say more about Joy Harjo, the Library’s current U.S. Poet Laureate. Joy occupies a position established in 1937 that has featured some of our nation’s greatest poets, including Gwendolyn Brooks, Rita Dove, Robert Pinsky and Tracy K. Smith. Joy is the first Native American to hold the position.

Her signature project is “Living Nations, Living Words,” and I invite you to explore its interactive map and collection of recordings featuring 47 contemporary Native poets from across the country. I’m sure you’ll be as inspired as I am by the voices it celebrates.

We are lucky to live in a moment in which the country contains so many poets laureate, a testament to the power of the Library’s laureate position and the many poets who have held it. This week, Amanda showed us the power of poetry and reminded us of what such positions as the National Youth Poet Laureate can offer the country. Kudos to her. I’m happy she stands alongside her poetry elders in promoting the art to all Americans.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Inauguration Stories: Lincoln’s 1865 “With Malice Toward None” Speech

Since it’s inauguration week, we’re looking at a few of the most important ones in national history.

We tend to see presidential inaugurations as staid events with a familiar refrain and symbolism. It wasn’t always that way — no one had any idea George Washington was going to give a speech after his 1789 inauguration as the nation’s first president — but the passing centuries have given the event a common ceremony and narrative arc.

Most inauguration speeches, like most all speeches, are not long remembered. But some are burned into the national memory, like Washington’s phrase, “the sacred fire of liberty,” from his unexpected speech.

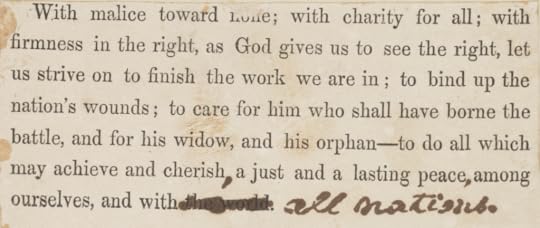

The last lines of Lincoln’s first inauguration speech, with “the better angels of our nature” in the last line.

Both of Abraham Lincoln’s inaugurations were memorable, in part because of his eloquence but in larger part because of the Civil War that was unfolding at his first inauguration and ending during his second. Both speeches featured phrases that are still quoted. In the first, there was “the mystic chords of memory,” and, no doubt the most famous, “the better of angels of our nature,” scrawled in at the very bottom of the last page.

As Michelle Krowl, the Library’s Civil War and Reconstruction expert, details in the video above, Lincoln took his second inaugural oath on March 4, 1865. The war was all but done. Robert E. Lee, the Confederate general, would surrender just a few weeks later on April 9. Lincoln would be assassinated six days later, on April 15.

This second speech, given after a morning of wet, miserable weather, took place on the East Portico of the Capitol. It was the first inauguration after the Capitol dome was completed, and it was the first at which African Americans — some wearing their Union army uniforms — were allowed to attend.

Lincoln’s vice president, Andrew Johnson, a former senator from Tennessee, took his oath of office in the Senate chamber around noon. The gathering then moved outside for Lincoln’s oath and address. The weather, so awful for most of the day, had calmed. Just before he began speaking, the sun came out, casting the day in a new light.

Abraham Lincoln delivering his second inaugural address. Prints and Photographs Division.

The typeset speech — Lincoln cut and pasted paragraphs onto the page — ran just 700 words and fit on a two-columned page. He stood behind a small metal table, put on his glasses and read. It could not have taken more than a few minutes.

Lincoln began with a recounting of the situation of his previous inauguration. He noted that “insurgent agents” had been in the city then, intent on tearing the nation apart. He soon got to the point of what the war had ultimately been about — slavery. Though he said that the government had not originally sought to abolish slavery before the war, just to limit its territorial expansion, it was now committed to destroying it:

“Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.”

Then, in his concluding lines, he turns to the future with hope. It was a vision of reconciliation, of renewed peace and of a nation united once more. The monumental phrase is “With malice toward none; with charity for all.” It was the perfect summation for a president trying to bring a fractured republic, then in the last throes of the war, back together.

The final lines of Lincoln’s second inaugural address, with handwritten notes. Manuscript Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

January 20, 2021

Inauguration Day: George Washington’s 1789 Oath of Office

Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress, uses George Washington’s 1789 copy of “Acts Passed at the First Congress of the United States of America,” which includes the U.S. Constitution, to tell a short story on how the presidential oath of office has been unchanged since the founding of the nation. It’s the same oath that Joe Biden will swear to today, 232 years later.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

January 16, 2021

Amanda Gorman Selected as President-Elect Joe Biden’s Inaugural Poet

National Youth Poet Laureate Amanda Gorman reads her work, “An American Lyric,” at the inaugural reading of Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith, September 13, 2017. Photo by Shawn Miller.

The following post by Peter Armenti, literature specialist for the Digital Reference Section, first appeared on our blog, “From the Catbird Seat: Poetry and Literature at the Library of Congress.”

The Presidential Inaugural Committee for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris has announced that former National Youth Poet Laureate Amanda Gorman will perform her poetry at the 59th Presidential Inaugural Swearing-In Ceremony, set to take place on Wednesday, January 20, on the West Front of the U.S. Capitol. Amanda, who was appointed the first-ever National Youth Poet Laureate in April 2017, will become only the 6th poet to perform at a presidential inauguration, and the first inaugural poet since Richard Blanco, who read his poem “One Today” at Barack Obama’s 2013 inaugural. She is also the youngest ever inaugural poet. Here is a complete list of previous inaugural poets and the poems they performed:

Robert Frost, who recited “The Gift Outright” (text) at John F. Kennedy’s 1961 inaugural. Frost recited the poem from memory after he was unable to read the text of the poem he’d written for the inauguration, “Dedication” (), because of the sun’s glare upon the snow-covered ground.Maya Angelou, who read “On the Pulse of Morning” (text; video) at Bill Clinton’s 1993 inaugural.Miller Williams, who read “Of History and Hope” (text; video) at Bill Clinton’s 1997 inaugural.Elizabeth Alexander, who read “Praise Song for the Day” (text; video) at Barack Obama’s 2009 inaugural.Richard Blanco, who read “One Today” (text; video) at Barack Obama’s 2013 inaugural.Amanda’s reading will be bookended by a rendition of the National Anthem by Lady Gaga and a musical performance by Jennifer Lopez. It will no doubt reflect and amplify the overarching theme of the presidential inauguration, “America United,” which, according to the Inaugural Committee, “reflects the beginning of a new national journey that restores the soul of America, brings the country together and creates a path to a brighter future.”

Amanda, we’re thrilled to point out, has a direct connection to the “From the Catbird Seat” blog. In her capacity as National Youth Poet Laureate she contributed a monthly guest post from October 2017 to April 2018 for the blog. Her connection to the Library of Congress does not end there—like the previous five inaugural poets, she has performed her work at the Library of Congress. Most notably, she served as the “inaugural poet” for the 22nd U.S. poet laureate, Tracy K. Smith, at Tracy’s 2017 inaugural ceremony. Tracy, who like Amanda is a Harvard alumna, had asked Amanda to read a poem to open the program. Amanda agreed, and wrote and performed a new and powerful poem for the occasion—”In This Place (An American Lyric).” You can view a video of Tracy’s inaugural below, skipping to 01:19 to watch Librarian of Congress Dr. Carla Hayden introduce Amanda. Amanda’s performance of the poem begins at 04:57:

{mediaObjectId:'5C66A315A9B9004EE0538C93F116004E',playerSize:'mediumWide'}While as of this writing the poetry that Amanda will read at President-Elect Biden’s inaugural is not known, I wouldn’t be surprised to see her perform “In This Place (An American Lyric),” which offers a much-needed message of hope and unity as this moment in American history. (UPDATE: A January 15 Associated Press article notes that Amanda was recommended as inaugural poet by Jill Biden and will perform an original poem for the occasion, titled “The Hill We Climb.” Read more here.)

Amanda was kind enough to publish “In This Place (An American Lyric)” in her October 11, 2017, blog post recounting her experience as Tracy’s inaugural poet, and I reproduce it below:

In This Place (An American Lyric)

There’s a poem in this place—

in the footfalls in the halls

in the quiet beat of the seats.

It is here, at the curtain of day,

where America writes a lyric

you must whisper to say.

There’s a poem in this place—

in the heavy grace,

the lined face of this noble building,

collections burned and reborn twice.

There’s a poem in Boston’s Copley Square

where protest chants

tear through the air

like sheets of rain,

where love of the many

swallows hatred of the few.

There’s a poem in Charlottesville

where tiki torches string a ring of flame

tight round the wrist of night

where men so white they gleam blue—

seem like statues

where men heap that long wax burning

ever higher

where Heather Heyer

blooms forever in a meadow of resistance.

There’s a poem in the great sleeping giant

of Lake Michigan, defiantly raising

its big blue head to Milwaukee and Chicago—

a poem begun long ago, blazed into frozen soil,

strutting upward and aglow.

There’s a poem in Florida, in East Texas

where streets swell into a nexus

of rivers, cows afloat like mottled buoys in the brown,

where courage is now so common

that 23-year-old Jesus Contreras rescues people from floodwaters.

There’s a poem in Los Angeles

yawning wide as the Pacific tide

where a single mother swelters

in a windowless classroom, teaching

black and brown students in Watts

to spell out their thoughts

so her daughter might write

this poem for you.

There’s a lyric in California

where thousands of students march for blocks,

undocumented and unafraid;

where my friend Rosa finds the power to blossom

in deadlock, her spirit the bedrock of her community.

She knows hope is like a stubborn

ship gripping a dock,

a truth: that you can’t stop a dreamer

or knock down a dream.

How could this not be her city

su nación

our country

our America,

our American lyric to write—

a poem by the people, the poor,

the Protestant, the Muslim, the Jew,

the native, the immigrant,

the black, the brown, the blind, the brave,

the undocumented and undeterred,

the woman, the man, the nonbinary,

the white, the trans,

the ally to all of the above

and more?

Tyrants fear the poet.

Now that we know it

we can’t blow it.

We owe it

to show it

not slow it

although it

hurts to sew it

when the world

skirts below it.

Hope—

we must bestow it

like a wick in the poet

so it can grow, lit,

bringing with it

stories to rewrite—

the story of a Texas city depleted but not defeated

a history written that need not be repeated

a nation composed but not yet completed.

There’s a poem in this place—

a poem in America

a poet in every American

who rewrites this nation, who tells

a story worthy of being told on this minnow of an earth

to breathe hope into a palimpsest of time—

a poet in every American

who sees that our poem penned

doesn’t mean our poem’s end.

There’s a place where this poem dwells—

it is here, it is now, in the yellow song of dawn’s bell

where we write an American lyric

we are just beginning to tell.

(This poem was first published by Split This Rock.)

All of us at From the Catbird Seat are thrilled to see Amanda, and (once more) poetry, take center stage at the inaugural events.

January 14, 2021

News! Library Wins 2021 Galvez Prize

Bernardo de Galvez. Undated, artist unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by María Peña, a public relations strategist in the Office of Communications.

The Library is the 2021 recipient of the Bernardo de Gálvez award, awarded annually by the Fundación Consejo España-Estados Unidos to American citizens or institutions who help promote and nurture relations between Spain and the United States, a stirring bit of international recognition for the work of the Hispanic Division.

This week, the organizers recognized the Library’s “valuable contribution to preserving the world’s bibliographic and documentary heritage,” in particular the comprehensive collection of items related to the Iberian peninsula, Latin America and the Caribbean.

“The Hispanic Division is honored to work with many colleagues in the Library of Congress and researchers across the country in acquiring, preserving and making available many different kinds of materials from and about Spain,” said Suzanne Schadl, chief of the Hispanic Division. “This recognition … is an acknowledgment of many peoples tremendous work.”

Let’s take a moment to remember who Bernardo de Gálvez was and his role as an unsung patriot and key ally in the foundation of the United States.

His military prowess was an outgrowth of the Hispanic presence in North America dating back to 1565, when Spaniards established the first permanent European settlement in what is now the continental United States, at St. Augustine, Florida. They settled in vast areas of the country and established towns, missions, trading posts, and infrastructure projects in over half of today’s states. During the Revolutionary War, while the Spanish government gave aid to the struggling colonial forces, his military exploits helped defeat the British in present-day Louisiana, Mississippi, Florida and Alabama.

Born to a wealthy family in Macharaviaya, a small mountain village in the southeastern province of Málaga, Gálvez grew up hearing stories about seemingly endless wars in Europe, in which Spain often sided with France against England.

Like many of his social set, he attended an elite military school in Ávila, where he was groomed for a career of battles and conquests on behalf of the Spanish royals. He came to the Americas as a teen, fighting on behalf of Spain, and was governor of Spanish Louisiana by the time he was 30.

“Prise de Pensacola,” Nicolas Ponce, 1784. Painting shows the munitions explosion at the British fortress. Spanish troops, possibly under the command of Gálvez, are on the attack. Prints and Photographs Division.

In the war, his strategy was a win-win effort: He provided much-needed weapons, uniforms, medicine and other supplies to the Continental Army, while he advanced the interests of Spain against a common enemy. He helped found Galveston, Texas, which was then named for him.

In 2014, Congress passed a bill awarding Gálvez honorary citizenship, 228 years after his death, joining eight other foreign leaders, including Winston Churchill and Mother Theresa. The joint resolution, signed by President Barack Obama, called him a “hero of the Revolutionary War,” highlighting his two-month siege of Pensacola, Florida in 1781, when he cut off British access from the south; the taking of the Port of New Orleans; and other feats that helped George Washington on the battlefield. When he drove the British from Pensacola, they never returned.

The Library’s vast Hispanic collections – one of the world’s most comprehensive – include more than two dozen manuscripts on Gálvez and his military accomplishments. Among the rare items is a 1781 letter in George Washington’s correspondence, from Gálvez to François Joseph Paul, Comte de Grasse, about the “capitulation of Pensacola” and the British prisoners’ “word of honour not to take arms.”

Gálvez’s pivotal role in the American Revolution is a testament of Hispanics’ long presence and contributions to the rich cultural tapestry of the United States, where they now number over 60 million and are the country’s largest minority.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

January 11, 2021

Free To Use and Reuse: The Art of the Book

From an 1830 copy of “Historia de Mexico,” by Juan de Tovar. Artist unknown. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

January’s Free to Use and Reuse sets of copyright-free prints and photographs is one of our favorites, as it beholds the beauty of the book. The book itself, of course, is one of mankind’s greatest inventions; the art that goes into the making, shaping, designing and illustrating of books around the world is another set of art forms. If you’re interested in seeing what other free prints and photographs the Library has online, just flip through the sets of them — travel posters are always a favorite, as are presidential portraits and the Gottlieb Jazz Portraits.

The collection of book images, meanwhile, gives a tour of the planet, of the dreams and images of people as they have evolved through time. And as far as craftsmanship: The inks and dyes in these images are often as brilliant today as they were when pressed to paper, cloth or vellum, often long before the United States existed.

Our first image stems from Juan de Tovar’s “Historia de Mexico,” first published around 1585. Library curators note that Tovar a famous Jesuit priest and missionary, an expert in the Nahuatl language who collected pre-Columbian Aztec codices. The original images in his “Historia” were made by the Aztecs.

The image above is a watercolor from an 1830 copy of the book from the staggering collection of Sir Thomas Phillipps, a wealthy British collector who had, at one point in the early 19th-century, perhaps the largest private collection of books in the world. (He was known to buy the entire stock of bookstores.) The colors here — the reddish maroons, the stark yellow — bring us into worlds gone by, when the Aztecs dominated what is now central and southern Mexico.

From “Milton: A Poem in 2 Books.” William Blake, 1811.

Speaking of worlds gone by, William Blake, anyone? The above hand-colored illustration is taken from the British painter/author/engraver/mystic’s “Milton: A Poem in 2 Books,” a stunning work finished in 1811. The book is in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, part of the Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection.

Blake’s work in this dazzling vision is to imagine — in poem, prose and art — a spiritual union with John Milton, the author of “Paradise Lost,” in a fierce quest to save “Albion,” or Britain. The preface contains a brief poem that recites the legend that Christ once visited Britain: “And did those feet did in ancient time/Walk upon England’s mountains green…” that was eventually used for the beloved hymn, “Jersusalem.” It’s still often called Britain’s second national anthem.

The muscular, dramatic illustrations over 50 pages were made with etched plates that were washed over with watercolors and a gray wash. As Library curators note: “(Blake’s) mature style depicts the struggles of human nature in its deepest psychological and spiritual sense and gives Milton’s poem a meaning unfathomable by most readers of his day.”

Here, you can see the orange coloring is often wide of the flames, giving the work a flash of Blake’s intense passion. It’s been on the page for more than two centuries and yet you can still feel the dazzling heat, the energy, the vision, that drove Blake like a man possessed.

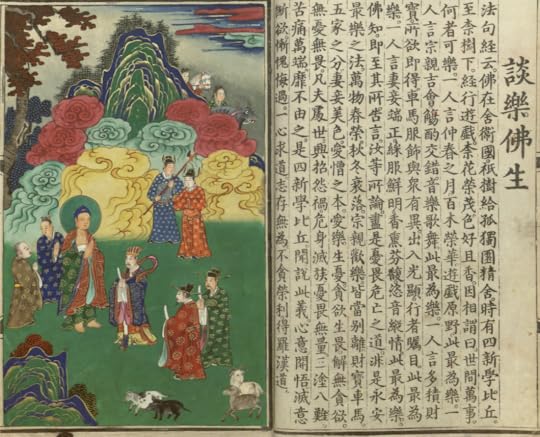

Illustration from “The Origin of Buddhism and Its Development in China,” circa 1486. Chinese Rare Book Collection, Asian Division.

Lastly, we come to China in the 15th Century.

This is a woodblock print from 1486 titled, “The Origin of Buddhism and Its Development in China.” The image is taken from volume 2 of the original 6 volumes of the work, and depicts Gautama Buddha during the period of his ministry. Buddhism originated in India more than 2,500 years ago, and likely migrated to China with Silk Road merchants and travelers some 2,000 years ago. The brilliant colors here — those blues! those greens! — are testament to the beauty hidden between book covers, patiently waiting through to the centuries to enchant viewers in a new age.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

January 6, 2021

Researcher Stories: Charles W. Calhoun and the American 19th Century

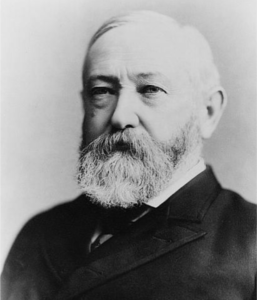

Historian and author Charles W. Calhoun. Photo: Bonnie Calhoun.

Charles W. Calhoun is Thomas Harriot distinguished professor of history emeritus at East Carolina University. He has spent countless hours immersed in the Manuscript Division’s collections. His discoveries have informed multiple books, including his most recent, “The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant.”

What first brought you to the Library?

I have long thought of the Library of Congress as my second home. My research in the Library’s Manuscript Division extends back more than 50 years. As an undergraduate at Yale University in the late 1960s, I wrote my senior essay on the political career of Walter Q. Gresham, a Civil War general, federal judge and cabinet officer. The Library holds a good-sized collection of Gresham’s papers, and I traveled by train from New Haven, Connecticut, to Washington, D.C., to examine them. I had previously used microfilm editions of the Manuscript Division’s collections of presidential papers, but now there I was, holding in my hands actual documents. I was hooked.

I can’t recall how many trips I made to the Library that year. I consulted not only Gresham’s papers but several other collections as well. Conducting this research and writing the essay was transformative for me. I switched my long-held career goal of becoming a lawyer to going to graduate school in history.

The Gresham essay wound up being the germ of my doctoral dissertation which evolved into my first book. My specialty is late 19th-century American political history, a subject for which the Manuscript Division’s holdings are particularly rich. Whenever I am developing a new project, one of the first questions is always: What pertinent collections are in the Library of Congress?

Over the years, I have used other parts of the Library, including the general book collection, the Law Library and the Newspaper and Prints and Photographs reading rooms — all of them, of course, superb. But I have spent most of my time in the Manuscript Reading Room. Its staff is absolutely top-notch.

Which collections have you used?

They are too numerous to list by name. For my Grant presidency book alone, I read more than 40 manuscript collections at the Library. Many of the presidential papers collections are quite large. But others rival them, including the 600-plus bound volumes of the letters of John Sherman, the senator and cabinet secretary. Some collections are small, comprising only a folder or two, but even these can yield useful gems. In addition to the Library’s own holdings of manuscripts, the division houses many microform editions of collections held elsewhere.

What are some of your favorite discoveries?

The examples abound, so I’ll mention just a few.

Benjamin Harrison in 1896. Prints and Photographs Division.

I was struck by how many of the ideas that Benjamin Harrison expressed in his college papers informed the policies he later pursued as a senator and president. The understated prose of Hamilton Fish’s diary takes us behind the scenes during the Grant administration — he served as Grant’s secretary of state. He not only brings policymaking and political maneuvering to life, but he also offers numerous choice nuggets, such as Grant’s thoughts of resigning within a year of taking office. In processing John Sherman’s papers, were the Library’s archivists dutifully preserving a manifestation of obsessive compulsion when they included a receipt Sherman kept for an umbrella he had left on a train? And the tiny collection of Jacob William Schuckers, private secretary to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Salmon P. Chase, contains a marvelous memorandum describing Sen. Charles Sumner as “an extremely intolerant man; a species of Sir Anthony Absolute in politics; very easy to get along with if you always humbly agreed with him.”

Tell us about your use of the presidential collections online.

In the era of shrinking research budgets and dwindling travel funds, the Library’s decision to offer these indispensable resources online represents a tremendous boon to scholarship. The shutdown associated with the COVID-19 pandemic underscores the wisdom of that decision. I am delighted to see that additional collections are being made available even while the Library is closed.

Viewing the materials online is a bit more cumbersome than flipping pieces of paper, but the payoff is the same. And you can do it in the comfort of your own home any time of day or night, seven days a week.

How would you advise researchers new to navigating the collections?

The reading rooms house finding aids for a great many of the collections. These describe in detail the materials in the collections (kinds of documents, dates covered and so forth), so that readers can target their research on what is pertinent. Over the past few years, the Library staff has updated and improved many of these finding aids. Many of them are also available online, so that one can plan one’s research effort in advance of making a trip to the Library (or in conjunction with using a digitized collection).

And, a point that is relevant to research in other repositories as well: You have to know cursive. Now that elementary schools are omitting instruction in this basic skill, graduate departments are enjoining their rising scholars to acquire it. But even for researchers of earlier generations for whom cursive is second nature, reading the handwriting found in historical collections can be challenging.

Oddly enough, I have discovered that many 19th-century newspaper editors suffered from terrible penmanship, sometimes making their letters practically illegible. Horace Greeley, John W. Forney and Murat Halstead seemed locked in competition for the prize for most indecipherable hand. Halstead’s letters are sometimes accompanied by a “translation,” perhaps prepared by a clerk to make them intelligible to the recipients.

But it is also true that handwriting may suggest something about an individual’s personality or character. I’m no handwriting expert, but it strikes me that Benjamin Harrison’s supposed cold rigidity may be reflected in his writing, which is precisely uniform but as jagged as a readout of an EKG. James Harrison Wilson’s brash egotism shines through in his bold, rounded, well-formed words.

What’s next for you?

I am currently working on a project examining the presidential elections of 1868 and 1872 won by Grant. I am particularly interested in these campaigns and elections as critical steps in the reconstruction of the American political system after its profound disruption by the Civil War and its immediate aftermath. Once again, the Manuscript Division is the first stop in the journey.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

January 4, 2021

Citizen DJ, Noah Webster and the Value of Copyright

Brian Foo, the Library of Congress 2020 Innovator in Residence and the creator of Citizen DJ, doesn’t always hang out like this. But it’s fun when he does. Photo: Shawn Miller.

It started, the story goes, with a back-to-school jam in the Bronx in 1973. There, in a basement rec room, DJ Kool Herc — aka Clive Campbell — stood between two turntables, switching between records to extend the instrumental breaks so his sister’s friends could dance longer. His parties became so popular he had to move them to clubs and even outdoors.

The movement he’s often credited with igniting — hip-hop — dominates music today. Fans can now mix their own beats from a source not often associated with the genre: the Library of Congress.

Citizen DJ, an experimental music sampling tool that launched on the Library’s website this summer, enables musicians to browse the Library’s collections — vintage audio, interviews, musical performances — and integrate them into their own productions.

The tool combines public-domain content — works available for anyone to use — with material copyright owners have consented to include. It is the brainchild of Brian Foo, computer scientist, visual artist and one-time break dancer. He’s also one of the Library’s innovators in residence, a program of LC Labs that encourages creative use of the Library’s digital collections.

“I was very much embedded in hip-hop culture and later in life appreciated sampling and collage and referencing as means for self-expression through historical interrogation,” Foo said.

Foo’s reuse of content carries out a vision from America’s earliest days. The framers wrote copyright into the Constitution to “promote the progress of science and useful arts” — that is, to add to the growing nation’s wealth of culture and knowledge.

Copyright law gives creators certain exclusive rights to benefit from their works for a limited time. After the copyright term expires, the works become free to use and reuse. By allowing early Americans to reap the rewards of their efforts — by selling their books or maps, for example — the framers intended to encourage creativity. By limiting the term of copyright protection, they aimed to make knowledge accessible and foster still more creativity.

Noah Webster, whose spelling book and dictionary became staples of American education. Prints and Photographs Division.

Noah Webster — famous for his dictionary — played an outsized role establishing copyright in U.S. law. On Aug. 14, 1783, Webster obtained a Connecticut copyright for his 120-page spelling book.

Webster’s small volume became America’s first bestseller — schools that had closed during the Revolutionary War were reopening and needed books. The first 5,000-copy print run sold out within nine months and, the following year, the book sold 500 to 1,000 copies a day. Webster’s earnings allowed him to support his family and compile his dictionary.

His state, Connecticut, was the first to enact a copyright law — individual states had such laws before copyright was written into the Constitution. After Webster registered his book, he toured the country to press other states and the new federal government to implement copyright laws. His efforts earned him the moniker “father of copyright.”

Jedidiah Morse, author of bestselling geographies, not long afterward earned the distinction of filing the first reported federal copyright case. Represented by statesman Alexander Hamilton, Morse sued New York City bookseller John Reid for selling a geography that borrowed liberally from Morse’s work. Reid was ordered in April 1798 to cease publishing the offending geography and to pay Morse $262.50.

The U.S. Copyright Office, which today administers the copyright system within the Library, oversees the world’s largest database of copyrighted works and copyright ownership information.

Like Foo, many of these creators drew on works of earlier artists. Edgar Allan Poe’s poems, for example, gave rise to a long list of musical compositions — “Nevermore” by the rock band Queen, “The Fall of the House of Usher” by composer Philip Glass, versions of “Annabel” by Frankie Laine, Joan Baez and Stevie Nicks.

Bob Dylan pays tribute in his music to poets William Blake, Robert Burns, Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman and Archibald MacLeish — a Librarian of Congress from 1939 to 1944. The web series “Epic Rap Battles of History” draws on Dr. Seuss, Dickens and other literary figures. Robert Frost’s poem “The Road Not Taken” has inspired pop music lyrics, episodes of “Twilight Zone” and “Battlestar Galactica” and more than a few commercials.

Foo’s ambition is to share the riches of the Library with new creative audiences. Citizen DJ features thousands of sound clips — each about a second long — from holdings across the institution.

Aspiring composers can draw on the Joe Smith collection, for example, featuring interviews with music legends such as Elton John, Ben E. King, Aerosmith. Or, they can use the Tony Schwartz collection of New York City soundscapes: honking horns, jackhammers, snippets of conversation. Or, they can incorporate audio from a Library musical performance by U.S. poet laureate Joy Harjo, who donated reuse rights to the performance.

“From a copyright point of view, we have a really high bar that we’re setting,” Foo said. “We want to be able to say from a legal point of view, you can use this material for creative reuse, even commercial.”

Like Foo, documentary filmmaker Elizabeth Coffman incorporates earlier works into something entirely new, a long tradition in filmmaking — the blockbusters “The Wizard of Oz,” the “Harry Potter” film series and “Avengers: Endgame” are but a few examples of motion pictures adapted from literary works.

Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden and Ken Burns present Elizabeth Coffman the Lavine/Ken Burns Prize for her film “Flannery,” 2019. Photo credit: Shawn Miller.

Last fall, Coffman was awarded the Library of Congress Lavine/Ken Burns Prize for Film for “Flannery,” a feature-length documentary she produced and directed with Mark Bosco about Georgia writer Flannery O’Connor.

Because of the film’s widespread distribution and broadcast potential, “I knew it needed copyright protection,” Coffman said.

Under current U.S. law, copyright protection takes effect the moment a work is created. But timely registration with the U.S. Copyright Office is required to secure certain remedies in cases alleging copyright infringement. So, Coffman registered “Flannery” with the Copyright Office once the film was completed.

That final step was probably the easiest task related to the film.

Telling O’Connor’s story required an intensive search for archival footage that was “funny, dark, weird,” reflecting the writer’s life and iconic fiction, Coffman said. Thanks to a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Coffman was able to hire two research assistants to help her track down materials, including “every photograph we could possibly find of O’Connor,” Coffman said. The grant also supported rights clearance, including payments to copyright owners for reuse of content, and the hiring of a composer and actors. Actress Mary Steenburgen narrated O’Connor’s voice. Three animators worked up graphics.

“Flannery had a good analogy for filmmaking,” Coffman said in her acceptance speech. “Writing is like giving birth to a piano sideways. Those who persevere are either talented or nuts.”

But in the end, Coffman said that documenting the writer’s place in American literature and winning the prize ended up being “one of the highlights of my life.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

December 30, 2020

Library’s Web Archiving: COVID-19 Challenges

This is a guest post by Joe Puccio, a collection development officer in the Collection Development Office.

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented challenges to the Library’s web archiving program not seen since the terrorist attacks against the U.S. on Sept. 11, 2001. The program had just begun in 2000, and the Library rushed to pull together online material from all across the country after the attacks. The resulting archive is part of the Library’s permanent collection.

Since then, the web archiving program has collected an enormous amount of materials (more than two petabytes of data and over 21 billion files) primarily in event or theme-based collections that are proposed, approved and set up in a process that can take several weeks to complete.

In mid-March, the Library’s reading rooms were closed and practically all staff began teleworking because of COVID-19. By that point, the Library was already capturing pandemic web content even before there was a formal collection plan in place. In addition, since the Library is a member of the International Internet Preservation Consortium, there was a desire to suggest sites for its global Novel Coronavirus collection. Our staff nominated sites for that effort. Also, by May, those same staff had recommended a substantial number of sites to be harvested for the Library’s collection, with more than 75 percent from outside the U.S.

Several things then became obvious.

First, we were rapidly expanding the number of sites to be collected, but still without a full collecting plan, as events were moving so fast. Second, the Library was approaching its crawling capacity under its current web harvesting contract. Third, there was growing uncertainty regarding the Library’s next annual budget, which had not yet been appropriated but was set to take effect on Oct. 1. Fourth, many other groups across the U.S. had already started COVID-19 archiving projects.

The Collection Development Office and the Web Archiving Team of the Digital Collections Management and Services Division developed a collecting proposal that took into account both the scope and funding of the project. Robin Dale, the associate librarian for Library Services, approved the plan in mid-June.

The plan has three primary objectives that are being carried out by a collection team led by subject experts from the Science, Technology and Business Division. The first objective is to fill major gaps in our pandemic web collection. The second is to determine high-priority sub-topics within the U.S. The final objective is to better identify and organize material we’ve already collected.

The team has been highly selective regarding new nominations, with a primary focus on the U.S. The team is also planning for the eventual public launch of the collection, which has a working title of the “Coronavirus Web Archive.” Since the Library’s web archives program observes a one-year embargo on harvested content, that collection will likely be made fully available in the latter half of 2021. Small parts of it will be available before the full launch.

The goal is to have a well-balanced collection of archived pandemic-related websites that will be preserved and made accessible to the Library’s users. Subject areas will include government information, social and cultural impacts, scientific material, personal narratives and everyday life. Examples of sites being collected:

U.S. Department of Education: Covid-19 Resources for Schools, Students, and Families

Pandemic Poems

Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium (BDCC)

Independent Restaurant Coalition | Save Local Restaurants Affected by COVID

American Farm Bureau Federation: Impact of Covid-19 on Agriculture

Together LA Festival

Eventually, the Library will have materials in its collections on this world-changing pandemic in a variety of formats, both physical and digital. Web archives will be prominent amongst them. If you’d like to submit your own collection of covid-related photographs, you can apply to this Library program.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

December 28, 2020

Curator’s Picks: Copyright

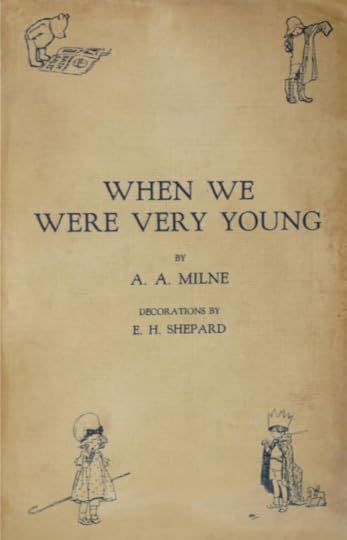

A.A. Milne’s “When We Were Very Young,” featuring the first appearance of the bear ultimately known as Winnie the Pooh.

George Thuronyi, the deputy director of Public Information and Education for the Copyright Office, chooses some of his favorite historical items submitted for copyright registration.

Aka ‘Winnie’

Alan Alexander “A.A.” Milne registered many works with the Copyright Office during his lifetime — plays, novels, short stories, music. In 1924, he published a collection of children’s poems, “When We Were Very Young,” inspired by his son and his stuffed animals. What makes this work meaningful is that it included the first appearance of a character, Edward Bear, Milne soon would make famous under another name: Winnie-the-Pooh.

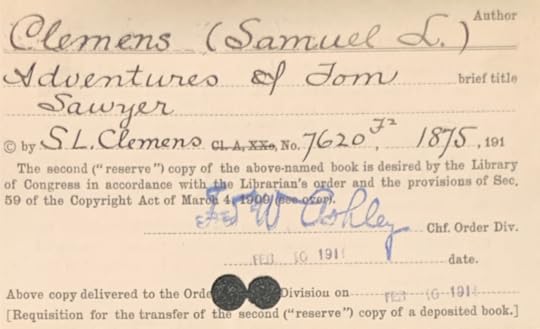

Twain’s Masterpieces

Twain’s Masterpieces

Mark Twain was a stalwart defender of authors’ rights and lobbied hard for international copyright protection, which finally was enacted in 1891. Detailed registration records for his literary masterpieces were painstakingly handwritten onto 4-by-6-inch catalog cards, including this one for “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” under the name Samuel Langhorne Clemens.

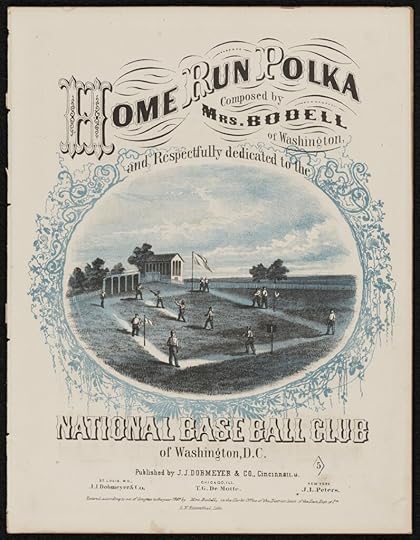

A Polka for Baseball

A Polka for Baseball

Perhaps no sport has inspired more music — and produced more copyright registrations — than baseball. This piece, “Home Run Polka,” was composed by Mrs. W.J. Bodell of Washington, D.C., and registered for copyright in a U.S. District Court in 1867. Bodell “respectfully dedicated” her polka to the National Baseball Club of Washington, a team of government workers, clerks, lawyers and war veterans who that year embarked on baseball’s first “tour of the West.”

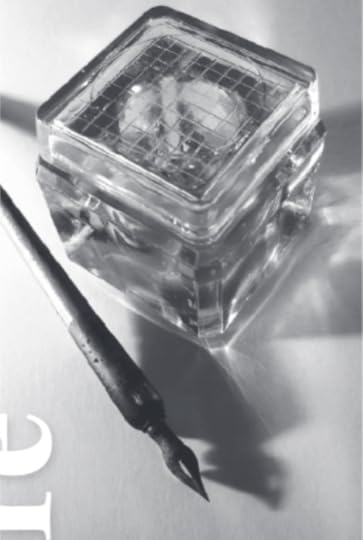

The long forgotten pen. Copyright file photo.

Tool of the Trade

In the early 20th century, Copyright Office clerks used dip pens to record copyrights in ledger books. A busy clerk likely left this one inside a manuscript for the George Scarborough play “What is Love?” when it was registered in 1913, and the pen remained tucked among the pages until it was discovered decades later. This style of dip pen also is notable because it was the inspiration for the Copyright Office seal used between 1978 and 2004.

Gloria Gaynor performs in concert at the Library on May 6, 2017: Shawn Miller.

“I Will Survive”

Gloria Gaynor scored a No. 1 hit in 1979 with this iconic dance-floor anthem of determination and perseverance. Dino Fekaris and Freddie Perren wrote “Survive” as a made-for-hire piece for Perren-Vibes Music Co., which submitted the original copyright application. Polydor Inc. submitted the application for the original sound recording of the single and for the album, “Love Tracks,” from which it was drawn. “Survive” was added to the Library’s National Recording Registry in 2015.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers