Library of Congress's Blog, page 50

December 23, 2020

A Visit from Santa…Who You Might Not Recognize

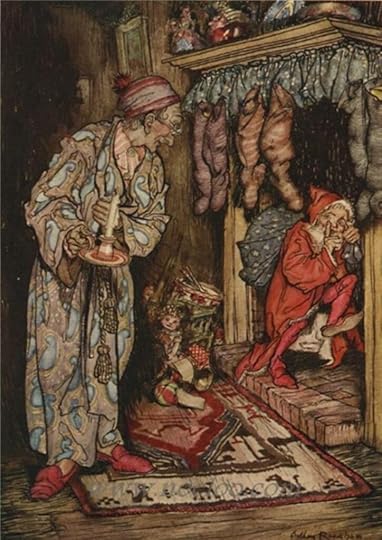

Santa, as described in “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” was a tiny, soot-covered elf who looked “like a peddler.” Illustration: Arthur Rackham.

Many thanks to Mark Dimunation, chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, for his research help with this post.

People are always talking about the “traditional” Christmas that used to grace the American landscape, one that was somehow more pure, more spiritual and not caught up in commercialism. The problem is, no one can agree when that was, other than “a long time ago.” Snow was whiter. Air was colder. People were nicer.

The seasonal theme, it seems, is nostalgia.

For example, in the ever-popular “White Christmas,” sung by Bing Crosby in 1942, even then he was longing for a season “just like the ones I used to know.” Certainly we wouldn’t go all the way back to the Puritans, who considered religious spectacles, particularly around Christmas, to be an apostasy.

How about the era of the Founding Fathers, even the early 19th century? Not quite. Christmas trees weren’t really a thing in the United States until the 1840s, and Christmas wasn’t even a federal holiday until 1870. Even then, there was a political angle. President Ulysses Grant (not exactly known as a pious teetotaler) made it a national holiday in an attempt to give the North and South something peaceful and kind to unite around after the Civil War.

But Santa, you say! Now, there’s a tradition! There’s a … soot-stained, pipe-smoking, pot-bellied elf, looking sketchy in a dirty fur coat? With miniature reindeer?

That was the man himself as depicted in “A Visit From St. Nicholas,” Clement Clarke Moore’s poem first published 197 years ago today. It’s better known by its first line — “The night before Christmas” — and has been a seasonal constant ever since. The Library’s card catalog lists more than 300 different editions/adaptations through the years, and that, boys and girls, is truly, undeniably, an American tradition.

But in Moore’s foundational, myth-making rendition, Santa is not the large, barrel-chested grandpa that we have known for the past century or so. Instead, Moore’s version of Santa was written during the midst of the Industrial Revolution, on the eve of the Victorian era and half a century before the creation of the light bulb. Santa, as we know him today, did not exist.

The poem was first published anonymously in the Troy (New York) Sentinel newspaper on Dec. 23, 1823. Moore, a Biblical scholar and wealthy real estate developer in Manhattan, eventually claimed credit nearly 15 years later. A friend had sent it into the paper without his knowledge, he later said, and, as an esteemed literary figure, he said the simple poem had been intended just for his children. (The family of Henry Livingston Jr., a military man and sometimes poet in New York, also made a later claim that Livingston was the author. Livingston himself died before Moore claimed credit. Some modern scholars support this view.)

In any event, here’s every description of St. Nicholas in the poem:

But a miniature sleigh, and eight tiny reindeer,

With a little old driver, so lively and quick,

I knew in a moment it must be St. Nick

and

He was dressed all in fur, from his head to his foot,

And his clothes were all tarnished with ashes and soot;

A bundle of Toys he had flung on his back,

And he looked like a peddler just opening his pack.

His eyes—how they twinkled! his dimples how merry!

His cheeks were like roses, his nose like a cherry!

His droll little mouth was drawn up like a bow

And the beard of his chin was as white as the snow;

The stump of a pipe he held tight in his teeth,

And the smoke it encircled his head like a wreath;

He had a broad face and a little round belly,

That shook when he laughed, like a bowlful of jelly.

He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf

One, let’s note that nowhere in the poem is “St. Nicholas” referred to as “Santa.” The actual St. Nicholas was a Christian saint, born in modern-day Turkey in the third century, who gained a reputation as a devout soul who was especially kind to children. His feast day was celebrated on the anniversary of his death, December 6.

Fast forward roughly 1,500 years. Some Dutch immigrants to New York gathered each year to celebrate his feast day, but with the Dutch nickname of “Sinter Klaas” (short for the Dutch “Sint Nicholaas.”) Washington Irving included this good-natured character in “A History of New York,” his satirical take on Dutch traditions in the region, published in 1809. Moore’s poem was written a few years later, and the jump from “Sinter Klaas” to “Santa Claus” had not yet been universalized.

Second, there’s no mention of the “fur” outfit being red, only that it’s covered in “ashes and soot,” which would render him — well, a grimy little mess. “Sinter Klaas” had no fixed appearance prior to this point, but was often portrayed as a thinner, sterner figure.

Here’s, he’s tiny and old, with a white beard, potbelly and a cheerful demeanor. In the 1931 illustration of the poem by Arthur Rackham at the top of this post, you can see something of how he was described, although by that point, Rackham skipped the soot-covered coat and the pipe.

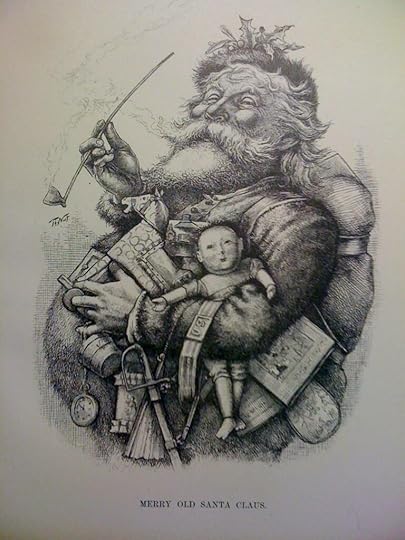

Thomas Nast, “Merry Old Santa Claus,” 1881. Prints and Photographs Division.

It was a full generation later that America got the Santa that we’d recognize today.

This image was the creation of Thomas Nash, often credited as the “Father of the American Cartoon.” (Nash also came up with the modern images of Uncle Sam, the Republican Elephant and the Democratic Donkey.) Note that “Santa Claus” by now was the character’s name. Nash introduced his sketches of Santa in Harper’s Weekly, and the image above first appeared January 1, 1881. It quickly attained a status akin to an official portrait. Many of the trappings of the Santa story were supplied by Nast’s drawings — his red coat, his pipe, his workshop, and even his North Pole location first appeared in Nast’s Santa vignettes. This made sense, as explorers had not yet reached the North Pole.

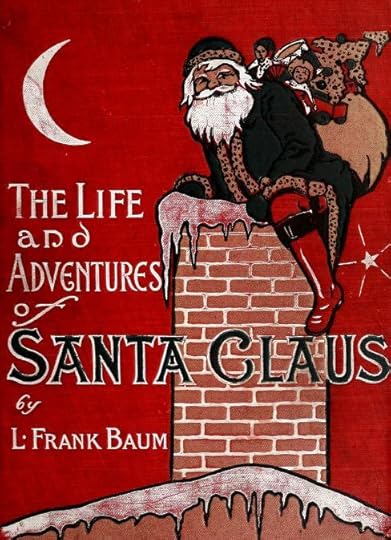

Later iconic renditions followed, such as in 1902 when L. Frank Baum (“The Wizard of Oz”) took a shot at an origin story with “The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus.”

Book cover of “The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus,” illustration by Mary Cowles Clark. Indianapolis: Bowen-Merrill, 1902

In Baum’s take, Santa did not begin life as a Greek/Turkish priest, but as a mythical creature tied into the world’s earliest mysteries. He’s found as a baby in the Forest of Burzee by Ak, the Master Woodsman of the World, and placed in the care of the lioness Shiegra. He eventually settles in the Laughing Valley of Hohaho (not the North Pole), delivers gifts to kids and is granted immortality. Here, in the illustration by Mary Cowles Clark, he’s rocking some serious red boots and pairing them with a stylish black coat with leopard-skin trim.

By that point, America had been seeing popular renditions of Santa for three quarters of a century, or about three generations. The children who had first read Moore’s poem were now grandparents or great-grandparents. The consensus had been reached on what he (mostly) looked like.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

December 22, 2020

A Seasonal Perennial: Who Invented Christmas Tree Lights?

A Christmas tree in the historic PNC Bank building, downtown D.C., ca 2000. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

We run the answer to this question every couple of years in the hopes of (peacefully) resolving holiday trivia disputeswhich may or may not occur at family gatherings, in person or online. This first ran in 2017.

Thomas Edison, inventor of the first successful practical light bulb, created the very first strand of electric lights. During Christmas 1880, strands of lights were strung outside his Menlo Park, New Jersey, laboratory, giving railroad passengers traveling by their first look at an electrical light display. But it would take almost 40 years for electric Christmas lights to become a tradition.

On Christmas Eve 1923, President Calvin Coolidge presided over the lighting of the National Christmas Tree with 3,000 electric lights. Prints and Photographs Division.

Before electric Christmas lights, families used candles to light their Christmas trees. This practice was dangerous, and led to many home fires. In 1882, Edward H. Johnson, Edison’s friend and partner, put together the very first string of electric lights meant for a Christmas tree. He hand-wired 80 red, white and blue light bulbs and wound them around his Christmas tree. Not only was the tree illuminated with electricity, but it also revolved.

But the wider world was not yet ready for electrical illumination—many people continued to greatly mistrust electricity. Some credit President Grover Cleveland with spurring the acceptance of indoor electric Christmas lights when in 1895 he asked for the White House family Christmas tree to be illuminated by hundreds of multicolored electric light bulbs.

Two children with a lighted Christmas tree in the middle of a train set. Prints and Photographs Division.

At the time, the wiring of electric lights was very expensive, requiring the services of a wireman, the equivalent of our modern-day electrician. Some have estimated that lighting an average Christmas tree with electric lights before the turn of the century cost $2,000 in today’s dollars. In 1903, General Electric began to offer preassembled kits of stringed Christmas lights, making their use more affordable.

Edison and Johnson may have been the first to create electric strands of lights. But it was Albert Sadacca, whose family owned a novelty lighting company, who saw a future in selling them. In 1917, when he was still a teenager, Albert suggested that the company sell brightly colored strands of Christmas lights to the public. Later, Albert and his brothers organized what became the National Outfit Manufacturers Association Electric Company. It cornered the Christmas light market until the 1960s.

This post draws on the science reference site, “ Everyday Mysteries: Fun Facts from the Library of Congress. ” Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

December 21, 2020

Free to Use and Reuse: Fun and Games

Will Rogers playing horseshoes. Photo Bain News Service. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Library’s Free to Use and Reuse sets of copyright-free prints and photographs collections are endlessly entertaining. Games for Fun and Relaxation, like travel posters, weddings, genealogy and so on, are yours for the taking. You can download them, make posters for your home or wallpapers for your phone. Christmas presents? Sure.

Let’s check out three.

Will Rogers was a multimedia star before the term existed. The Oklahoma-born member of the Cherokee Nation was a hugely popular film actor, author, Broadway star, standup comedian, newspaper columnist, lariat twirler and horse rider. He traveled internationally as a young man, working as a trick rider in circuses in South Africa and Australia, before returning home to become a megawatt celebrity.

His one-liners are as famous as those of Mark Twain, to whom he is often compared. “I am not a member of any organized political party. I am a Democrat.” “Last year we said, ‘Things can’t go on like this,’ and they didn’t, they got worse.” “I never met a man I didn’t like.” He opened his act with, “All I know is what I read in the papers.”

You can hear him roast a convention of bankers in New York in 1923, addressing them as “Loan sharks and interest hounds.”

“You are without a doubt the most disgustingly rich audience I have ever talked to, with the possible exception of the Bootleggers Union, Local No. 1, combined with the enforcement officers,” he told them.

The self-described “cowboy philosopher” died doing what he loved — flying planes. He perished with famed aviator Wiley Post on a seaplane trip through Alaska on Aug. 15, 1935. They were taking off from a lagoon in the late afternoon. The plane flipped. Both men were were killed instantly. Rogers was 55.

Above, we see him at his ease, playing a game of horseshoes. There’s no city or date information on the photograph, although the image is from Bain News Service, which tended to focused on New York City and was most active from 1900 to the mid 1920s. The event looks official — there is chalk marking the boundaries, and his right foot is near an iron stake that his opponent would have tossed at — and he’s leaning forward, intent, ignoring the crowd of men and boys surrounding him. Check out those two teens in short pants and white shirts, one guy with his arm slung around the other. You just want them to be skipping school for this. Rogers is wearing a fedora and a tie, but he has removed his suit coat. As a man who made his mark riding horses, you know he’d want to toss a danged horseshoe better than any city slicker.

Girls playing hopscotch. Flatbush, New York, 1942. Photo: Marjory Collins. Prints and Photographs Division.

Hopscotch was and is a beloved sidewalk game, known to children for ages. This photograph captures a picturesque day in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn. The girl in action is Chinese-American, the caption information tells us, and that she is playing in front of her house. She appears in the middle of the photograph, and appears to be the middle in age of her two playmates. It’s mid-morning or mid-afternoon, judging from the length of the shadows. (I’m going with mid-morning, as two of the girls appear to be wearing long-sleeve cardigans.) In the background, the woman walking towards the camera is carrying two bags of groceries; the gentleman in suit coat and pants appears to be wearing a Panama hat. In short, a regular summer day.

But … wait a minute.

The date on the photograph — August 1942 — tells us we’re in the middle of World War II, as does the credit line, the U.S. Office of War Information. That tells us that this almost certainly a planned photo shoot, rather a feature photography happenstance.

That month, news of the war was grim. The Nazis were beginning their siege of Stalingrad. They executed roughly 1,000 Jewish people in Stanislawów, Poland, as part of the Holocaust. The U.S. had just invaded Guadalcanal, part of the Solomon Islands, setting off one of the most vicious battles of the Pacific theater.

So, a regular summer day revisited: In August of 1942, the United States Office of War Information wanted to project the idea that the American home front was quiet, peaceful and a place where little Chinese-American girls could play hopscotch on the sidewalk with no worries at all. Rather than just a peaceful image, it was more likely a manufactured image of peace.

Buckaroos playing poker on the Ninety Six Ranch, 1978. Photo: Suzi Jones. American Folklife Center.

Lastly, we have this terrific image of cowboys playing poker in 1978 at the Ninety Six Ranch in northern Nevada from photographer Suzi Jones. It’s part of the American Folklife Collection, “Buckaroos in Paradise: Ranching Culture in Northern Nevada, 1945-1982.“

That collection includes dozens of motion pictures, sound recordings and more than 2,400 photographs. It focuses on Paradise Valley, which is both the name of a cattle-ranching valley and a crossroads community in Humboldt County.

Here, an open window provides the lighting for a midday poker hand, with a wood block doubling as a table and an empty cot doubling as a chair. You get the feeling that not a lot is at stake here, just a lunchtime diversion, but you never know. Those fellas aren’t all hat and no cattle.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

December 18, 2020

My Job: Rosemary Brawner in Copyright

Senior information specialist Rosemary Brawner helps the public understand copyright. Photo: Stan Murgolo.

Senior information specialist Rosemary Brawner helps the public understand copyright. Photo: Stan Murgolo.

Describe your work at the Library.

I am a senior information specialist in the Public Information Office at the Copyright Office. I provide expert guidance and advice on copyright regulations, policies, practices and the law. I am also a card-carrying member of the Guild and serve as its treasurer.

To have a great workplace and good morale, there has to be a balance between the organization’s and the worker’s needs. I like that I play a role in keeping that balance.

How did you prepare for your position?

In the beginning — 30-plus years ago — I didn’t desire to be an information specialist or the treasurer. I was young and had a baby, and I needed a job. I think it was lucky for me to find a job here since I love books and was in awe of the world-renowned Library of Congress.

I started temporary in the Congressional Research Service and then got my first permanent job in the Copyright Office in B-14 (where the applications were housed). I was like a sponge — if I had a question, someone in the office would answer me.

As my career progressed through the Copyright Office and doing labor union work, I knew that I wanted to help people. I worked hard to gain the experience that I needed to apply for the job. I believe that I applied for the job at least three times before getting it.

Once I joined PIO, if I didn’t know the answer to a question, I was determined to find the answer. Each day, I start off saying, “They are calling because they don’t know, so I’m gonna give them the best and correct answer.” To this day, I remember that there was always someone to answer my questions, so I make sure that I’m available to answer someone else’s questions.

What have been your most memorable experiences at the Library?

You mean meeting James Earl Jones, Chuck Brown, George Clinton, Fantasia, or speaking with Chuck Berry and Tom Benson on the telephone? No, the best memories are my interaction with staff at the Christmas parties, retirement parties, impromptu lunch meetings and outdoor events.

I like being a mentor to the work-study students and them tutoring me on “new math” and the current lingo. I like chance meetings and sharing greetings or a joke with the Librarian of Congress, Dr. Charles in the health office and other staff.

Why is sharing copyright information important to you?

Overall, I want to help people understand copyright. I like knowing that I provided a little knowledge to a person each day. I think copyright is underrated — copyright is the Cinderella team at March Madness.

My role is similar to a coach. I help the experienced players explode into stardom, the average players hone their craft, the rookies nail down the basics and fans have the best experience possible. If the team loses, I lose. If the team wins, I win.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

December 17, 2020

Mystery Photos…Solved!

Cary O’Dell at the Library’s National Recording Registry runs our Mystery Photo Contest. His most recent post, a Thanksgiving Edition, included 14 of his last 30 mystery pictures. Here’s his update.

Greetings all!

Thanks to your hard work over the past month, we solved five of 14 Mystery Photos posted just before Thanksgiving. That’s remarkable, particularly considering that readers already have figured out more than 95 percent of the original cache of 800 unidentified show business stills that we’ve been working to identify.

We’re now down to 25 pictures and we’ll post a selection from those in January. If you’d like to review the set of pictures we posted on Thanksgiving, click the link above. Meanwhile, enjoy these stories of five solved mysteries.

Marta Brennan

While it is wonderful to solve any of our mysteries, this one was especially pleasing. The identify of this All-American looking young lady had bedeviled us for the longest. We worked our way through a litany of guesses over the past few years, including Karen Valentine, Judy Strangis, Jody Fair, Dolly Read and even Joyce McKinney. To many people—including me—this lady “looked” British. Hence, I looked up many names from the British Isles, including Barbara Flynn, Janet Munro, Lalla Ward, Maureen O’Brien, Helen Worth, Suzy Mandel, and Janice Nicholls.

Finally, the magic eye of blog reader Collin Larsen identified her as Marta Brenna, an American actress. Brennan’s sole TV credit was a small part in the 1978 star-studded mini-series “Centennial.” She also worked and toured in various stage productions. Today, she’s the editor of a film industry newsletter. I reached out to her there and she confirmed that this is indeed her. Great job, Collin!

Brennan said she though this picture was taken around the time she was touring with Ray Walston in “You Know I Can’t Hear You When the Water is Running,” a set of four one-act plays by Robert Anderson about sex and relationships. (Walston himself was a character actor who appeared in dozens of hit film and television series, perhaps most famously as Uncle Martin in “My Favorite Martian” in the 1960s and, of course, as Mr. Hand, the buzz-killing teacher in 1982’s “Fast Times at Ridgemont High.”)

Tony (Anthony) Costa

Collin Larsen did it again when he plucked the name of musician Tony (Anthony) Costa out of the ether for this long-unknown pic. Costa’s son, Chad, also a musician, confirmed that that was his dad and we dutifully crossed it off the list.

Costa grew up in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and was known as a promising musician when he was a teen, appearing on local radio stations. A pianist, guitarist, vocalist and arranger, Costa formed the Town Pipers, a popular group in the 1950s. They performed in Las Vegas and Hollywood, appearing on “Tonight with Steve Allen,” the precursor of the Tonight Show. He eventually returned to Scranton and performed for years at nightclubs and recorded an album. Upon his death in 2014, the Scranton Times-Tribune dubbed him a local “musical icon” in his obituary.

“Fence Fixin’ ” — Oil painting by Luther F. Kepler, Jr.

Luther J. Kepler, Jr.

We had something of a leg-up with the photo of this painting, as we could make out the signature of the artist in the lower right-hand corner. “Kepler.” But Kepler who?

An early internet search sent us to painter Fred Kepler but he said it was not his. Then we thought this might have been a significant prop in some long-forgotten film or TV episode. Not that we could find.

But then sharp-eyed blog-reader Brenda Zook saw our Thanksgiving post! She did some adept detective work, identifying this as an early 1960s oil painting called “Fence Fixin’ ” by Pennsylvania artist Luther F. Kepler, Jr.

A native of central Pennsylvania’s Big Valley area, Zook said that she recognized the landscape and the Amish subjects. She was also familiar with the work of local artist Anne Fisher, which this painting greatly resembled.

Some online searching revealed that Fisher’s maiden name was Kepler. Aha! More online “doodling,” as Zook described it, turned up the records of a 2012 book auction at the Old Country News Library in Gordonsville, Pennsylvania, that included, among hundreds of other items, a July 1961 edition of “Mennonite Life” magazine. The auction description of the item said it included a short essay and several reproductions of paintings by Luther and Anne Kepler, but that was it. The auction listing included no images. Zook, though, was not about to quit now. She searched until she found the entire magazine online in the archives of the Mennonite Church at Bethel College. And there, lo and behold, was “Fence Fixin’.”

Great work, Brenda!

Kanza Omar

Ah, the lady in repose. This was another one I was about to give up on.

But then Collin Larsen (yes, him again), threw out a name: Kanza Omar.

Intrigued, I looked it up. Kanza Mary Omar was born in Marrakesh, Morocco, in 1912, moved to the U.S. when she was 11 and became a dancer and actress. She worked steadily enough but never quite hit the big time. Her list of IMDd credits totals only seven films and though some of them are very well known (“To Have and Have Not”), she went uncredited in all of them. Mainly, she toured the U.S. alone or with her dance company, introducing audiences to the “exotic” dances of other lands.

She was mentioned in newspapers a few times — when she became a U.S. citizen in 1943, and again in 1949, when she divorced her husband. One of their problems, she was quoted as saying, is that he had “no appreciation for her art.”

She passed away in 1958, at just 46, of a brain tumor. She left no heirs.

Collin wasn’t fully sure of this one. But two other intrepid researchers — devoted blog reader Andy Leahy and the Library’s own Laurel Howard — picked up the trail and went picture hunting on the web. One of the first things that popped up was a 1951 photo of “Princess Kanza Omar” in which she’s wearing the identical outfit/costume she is in the mystery photo. That’s one of our identifying criteria, so, ta-da! Another one of the list. Great job, all!

From left to right: Michele Metrinko, an unidentified gentleman, and Marsha Metrinko. Time, place and photographer unknown.

Michele and Marsha Metrinko

I had very little hope for solving this one, as I wasn’t at all sure it was related to show biz at all.

Certainly these two young women look pretty enough to be in a pageant. And, in fact, they were! Early on in our online guessing game, it was suggested that the lady on the left was 1963 Miss USA, Marite Ozers.

I reached out to Ozers, who looked at the photo and said it wasn’t her. Rats.

But wait! Ozers wrote in the blog’s comments that the woman on the left was actually her Miss USA runner-up Michele Metrinko. I took up the search from there.

Michele Metrinko has had an amazing career. She became a government lawyer, business executive, philanthropist and a high-profile political activist on the Republican side of the aisle in Delaware. She married John Rollins Sr., the founder of Orkin Pest Control. Her real estate holdings in Jamaica include the famous Rose Hall resort in Montego Bay.

Meanwhile, heroic reader Andy Leahy saw Ozer’s comment and used Google images to look up Metrinko. There, he quickly noticed pictures of Michele’s sister, Marsha, who looked like the woman on the other side of that Hawaiian feast. And what you know, Marsha Metrinko confirmed that was the two of them! Alas, neither of them remember the man in the middle, or when and where this photo was taken. Still, we’re counting this mystery as solved. That’s so much, Andy, Collin and former Miss USA, Marite Ozers!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

December 14, 2020

“The Battle of the Century,” Laurel and Hardy’s “Lost” Classic, Enters The National Film Registry

The climatic pie fight from “Battle of the Century,” with Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy in the middle of the action. Hal Roach Studios.

“The Battle of the Century,” Laurel and Hardy’s 1927 silent short film, famed for its epic pie-in-the-face fight sequence, quickly disappeared after its theatrical release.

The 20-minute, two-reel bit of comic relief in the latter days of the Roaring Twenties got left behind in the rush to talkies, as did most silent films. The last known surviving copy of its famed second reel was considered lost for good by the 1960s. It seemed to be a flickering bit of entertainment lost to time, disintegrating film stock and a too-late appreciation of an outdated art form. Slate magazine once described the missing second reel, containing most of the pie-fight sequence, as “one of the most deeply mourned lost treasures in film history.”

But after a California collector and historian named Jon Mirsalis stumbled across a copy of the second reel in 2015, the near-complete version of “Battle” today enters the gates of cinematic eternity, as a highlight of the 2020 class of the Library’s National Film Registry. That designation, announced by Librarian Carla Hayden this morning, caps one of cinema’s most unlikely fairy-tale endings.

” ‘Battle’ is such a well-made film with top-notch people working on it, many of whom went on to great careers,” says Rob Stone, moving image curator for the Library, talking about the film’s place in history. “It also makes for a good example to talk about how silent films were constructed, the progression of Laurel and Hardy’s work and, besides, it’s a feel-good story about how ‘lost’ films aren’t really lost. Maybe it’ll get people to start looking under their beds for other ‘lost’ things.”

Mirsalis, a toxicologist by profession and film collector by avocation, after he threaded the reel into his home film projector and saw the full pie-fight sequence: “I was watching with my jaw hanging open.”

Other 2020 entrants into the registry include pop-culture classics “The Dark Knight,” “The Blues Brothers,” and “Grease,” as well as 1918’s “Bread,” by director Ida May Park and Wim Wenders’ 1999 documentary about aging Cuban musicians, “Buena Vista Social Club.” Since the creation of the National Film Preservation Act, 800 films have been added to the registry for their contributions to the cultural, historic or aesthetic history of American cinema. The preliminary selections are made by the National Film Preservation Board and a cadre of Library specialists; the Librarian makes the final cut.

Turner Classic Movies is hosting a special Tuesday, Dec. 15, starting at 8 p.m. EST, to screen a selection of this year’s entries. Hayden and TCM host Jacqueline Stewart will introduce six films as part of the mini-marathon.

First up? “The Battle of the Century.”

It’s a fitting pride of place. When Mirsalis announced that he’d found the reel at the Library’s “Mostly Lost” film conference in 2015, the audience gasped. Newspapers and magazines wrote features. Film historian Leonard Maltin had found reel one in the 1970s in a collection at the Museum of Modern Art. He was astonished Mirsalis found its companion four decades later. “It’s been a holy grail of comedy,” he told the New York Times.

Since then, the nearly complete film (missing only a few short bits) has been pieced together from the collections of the Library, MOMA, the University of California at Los Angeles and other sources. It’s for sale on a variety of formats, often as part of larger anthologies.

The film’s storied history started simply enough. In 1927, Hal Roach Studios put together comedians Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, the beginning of what would become one of Hollywood’s most famous on-screen pairings. One of their first projects was “Battle.”

The plot: Hardy takes out an insurance policy on Laurel, his partner and a lousy boxer, and tries to engineer an “accident” that will result in a modest injury but a hefty payout. This being sketch comedy, Hardy starts throwing banana peels in Laurel’s path. One of these lands in front of a delivery man exiting a pie shop with a tray of – you guessed it – custard pies. He slips, gets up and soon shoves a pie in Hardy’s face. Hardy retaliates with a thrown pie but misses, instead hitting a passing young woman on the rump. Incensed, she grabs a pie from the delivery truck, flinging it at Hardy but hitting someone else. The fight escalates with each new victim’s throw missing its retaliatory target, instead hitting yet another innocent, who enters the fray with indignant but inaccurate results. It was farce, it was slapstick, it was a gag in which some 3,000 pies were thrown.

In 1927, people liked it fine but that was about it. Silent films of the era were routinely melted down to their chemical basics after their theatrical runs. The practice was so pervasive that 75 percent of all silent films are now believed to have been lost forever, according to a 2013 study by the Library.

But “Battle” wasn’t so quickly forgotten. As Laurel and Hardy’s fame grew and the decades passed, “Battle” became an outsized myth – that huge pie fight that everyone remembered but so few had actually seen.

In 1958, film historian Robert Youngson obtained a print of the second reel of “Battle” from the film studio as part of his research for putting together an anthology called “The Golden Age of Comedy.” He included a few clips from that reel in the final cut of his film. For decades, those clips were the only thing anyone saw of “Battle.”

Shortly thereafter, the studio’s nitrate negatives of “Battle,” by then more than thirty years old, completely decomposed. It was presumed that the film, like so many of its peers, was gone forever.

However, while it was well-known in the small world of film collectors that Youngson had made prints of his clips from the second reel – they were bought and sold – no one knew about that complete copy of the second reel he had obtained from the studio, all 400 feet of it. At the time, Mirsalis points out, no one was particularly looking for it, either. Definitive histories of Laurel and Hardy’s work had not been published, so no one knew how rare it was, including Youngson.

When Youngson died in 1974, his huge collection was bought by three other collectors: William K. Everson, Herb Graff and Gordon Berkow. Berkow ended up with most of the silent film. By then, it had been established that “Battle” appeared to be lost to history and there was a clamor to find it. But if Berkow ever saw the small, round film canister labeled as “BATTLE OF THE CENTURY R2” among the hundreds of others in the collection, it apparently never registered.

Berkow died in 2004 with the treasure still buried among the other 2,300 films in his collection. After the collection spent a decade in storage in New Jersey, his heirs shipped it out to Mirsalis’ California home for him to liquidate.

The films, collectively, weighed several tons. They almost completely covered the floor of his small home theater. The stacks were waist high.

“You could barely walk through the room,” he remembers.

The work was difficult, in part because the written inventory of the collection was in such disarray. It included more than 350 films that weren’t listed and missing some 200 that were. Given that, Mirsalis had no choice but to spend months threading up each roll of film and projecting it to make sure of what he had in front of him.

When he finally saw the canister labeled “Battle…R2” he assumed it was just a copy of the long-ago clips that Youngson had made. That was no big deal.

Still, he threaded up the film, turned on the projector … and made one of the great discoveries in film history.

“Your brain is going,’ he remembers of that moment, being the first person to see the missing reel in decades, ‘This can’t be real.’ ”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

December 10, 2020

Dolly Parton: “The Library That Dolly Built”

Dolly Parton reads to children in the Library’s Great Hall in 2018. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Dolly Parton’s documentary about her world-class book giveaway program for young children debuted on Facebook this week, highlighting her Imagination Library’s 25-year history and its ties to the Library.

“The Library that Dolly Built” chronicles how Parton, the child of impoverished parents (her father was illiterate) in rural Tennessee, built an international program that has given away more than 150 million books to young children since its 1995 inception. The program is simple: Participating children receive one free book by mail each month from birth until age five, regardless of income.

The program began in Parton’s native Sevier County, in the Smoky Mountains in east Tennessee, with a first order of 1,760 books. By 2001, it was operating with 27 affiliates in 11 states. The organization gave away its one millionth book in 2006; a decade later, it was mailing that many books each month. It’s now working across the United States and in Australia, Canada, Great Britain and Ireland.

Parton is a frequent guest at the Library — the Imagination Library was a 2014 recipient of the Library’s Literacy Awards — and stopped in for a day’s worth of programs in 2018, donating the program’s 100 millionth book to the Library’s collection. She took the stage with Librarian Carla Hayden for a talk about the program for the occasion.

{mediaObjectId:'6700973D31DF00EAE0538C93F11600EA',playerSize:'mediumWide'}

She also spoke with the Library’s Gayle Osterberg for a charming 10-minute segment about the program’s origins, including its ties to one of her signature songs, “Coat of Many Colors.”

.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

December 7, 2020

On the Passing of Sen. Paul Sarbanes

Sen. Paul Sarbanes, right, with Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden (then-executive director of the Enoch Pratt Free Library)

I am deeply saddened by the passing of Sen. Paul Sarbanes of Maryland.

In addition to his distinguished Congressional career, Sen. Sarbanes served with his wife Christine on the Enoch Pratt Free Library board in Baltimore and was a staunch supporter of literacy, an advocate for libraries, and a champion of lifelong learning. As Executive Director of the Pratt Library, I have enjoyed a long friendship with Sen. Sarbanes and his family and will remain immeasurably grateful for his support on my appointment as Librarian of Congress in 2016.

On behalf of the Library of Congress, we want to offer our deepest condolences and prayers to our congressional colleague, Rep. John Sarbanes, and to all of Sen. Sarbanes’ family.

Jason Reynolds: Grab The Mic, December Edition

This will be a short newsletter.

This will be a short newsletter.

One thing I don’t recall ever being told by any adult in my life when I was a kid, was to rest. Other than the forced nap time in nursery school and kindergarten, rest always just seemed like something I crashed into after expending every ounce of energy. It was the thing that happened when the sugar wore off. But there was never a moment when someone sat me down and explained why rest is important. And because it was never taught to me in the same way the importance of vegetables and kindness were, here I stand older than I’ve ever been with absolutely no clue how to do it.

But I’m going to learn. And to start, I’m taking a month off from writing this newsletter. So there won’t be one in January because I’ll be … resting.

What I’d love is for some of you to try it with me, this resting thing. Maybe once a day, turn off your phones and computers, close the books I know you’re reading and just sit still. Let’s all try to do it for five minutes a day. Just let your mind and body do nothing for a moment. I’m, of course, going for the gold and going to try to do this for a few hours each day, but knowing all of you are shutting down for five minutes will make me feel less anxious, like we’re all in this thing together. A communal rest, stretching across cities and states. It’s a beautiful thing to imagine, all of us who are normally connected by movement and activity, by voice and touch, by computers and cell phones, now connected through calm.

Because we can be. Because we have to be. Because now that I’m older than I’ve ever been, I realize giving your mind and body a moment of ease is just as important — as healthy — as vegetables. As important as kindness. Or maybe the most important kindness — the kindness of self.

And if an adult has never told you this, if you’ve never known that the brain needs breathing time to continue to do brain stuff, or the body needs moments to heal itself from your constantly bumping it into everything around you, if you’ve never thought of resting as an important choice for you to make, well, that’s what you’ve got me for. I’m pretty much your restie bestie. Yep … that’s my new title: Jason Reynolds, the Inaugural National Restie Bestie, here to encourage you to learn to calm your own fire so you don’t burn up everything around you or burn out everything inside you.

This is what love sounds like.

Until February, Happy Holidays and rest easy.

Jason

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

December 2, 2020

Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” – “Wait for Nod”

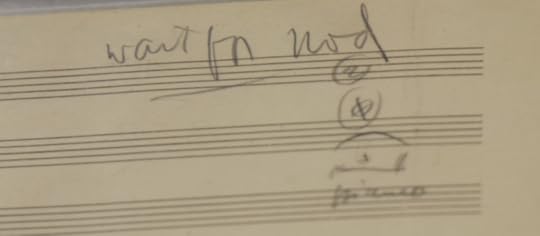

The first page of George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue,” in pencil. Music Division.

At some point during the hectic composition of “Rhapsody in Blue,” one of George Gershwin’s masterpieces of 20th-century American music, the maestro got impatient with the process. The piece, which was to debut in just a few short weeks, would eventually run to 22,000 notes over 500 measures, after all.

In Gershwin’s handwritten score of “Rhapsody,” he sketched out the notation for his piano solo but left a small section blank in the second draft, as by then copyists were helping notate each change that he was making as the piece came together. That solo section stayed blank in the third and final score arranged by Ferde Grofé, with only a note to conductor Paul Whiteman to “wait for nod” when Gershwin launched into his solo.

The “wait for nod” note marking Gershwin’s solo. Photo: Shawn Miller.

It’s a charming moment. Gershwin, 25, performing his first major concert piece, would wing it for a few measures, then give a tilt of the chin to Whiteman, the most famous conductor of the era, to bring in the rest of the band back in.

“It’s sort of like Babe Ruth calling his home run,” says Ray White, a music specialist in the Performing Arts Division, looking over “Rhapsody” manuscripts on a recent afternoon.

The Library’s vast collection of papers documenting “Rhapsody’s” birth has been a boon to researchers, academics and fans for decades. But the Library, which has prominent pieces of the George and Ira Gershwin Collection on long-term display, has now digitized George Gershwin’s original manuscript copy. It’s in pencil, with his neat, all capital block lettering spelling out “RHAPSODY IN BLUE – FOR JAZZ BAND AND PIANO” across the top of the first page. It’s dated Jan. 7, 1924, a few days after Gershwin reluctantly agreed to compose a piece for an upcoming concert by Whiteman’s band.

The Library also has the papers of Grofé, who not provided the score not only for the debut, but also for the 1942 lush, orchestral version of “Rhapsody” that quickly became the standard rendition.

Taken together, the two collections give the Library all three manuscripts of “Rhapsody” leading up to its historic debut on the afternoon of Feb. 12, 1924, at Aeolian Hall, before a packed crowd of 1,100 that included musical luminaries such as Igor Stravinsky, Leopold Stokowski, Fritz Kreisler, John Philips Sousa and jazz pianist Willie Smith.

No recording exists of that performance, but you can listen to Whiteman’s orchestra playing a shortened version of this arrangement on the Library’s National Jukebox. Recording limitations of the day required the piece be truncated; be sure to listen to the second part as well.

George Gershwin, 1937. Photo: Carl Van Vechten.

The story of how such a grand piece came together in just five or six weeks has been the subject of any number of books, musical studies and pop-culture folklore. The central debate turns on how much the young Gershwin wrote and how much the veteran Grofé completed.

“The harmonies, the melodies the rhythms — those are all Gershwin,” said Ryan Raul Bañagale, author of “Arranging Gershwin: ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ and the Creation of an American Icon,” and director of Performing Arts at Colorado College. He researched the Library’s “Rhapsody” holdings as part of his doctoral research at Harvard University. “But Grofé selected almost every instrumental assignment outside of the piano.”

Part of this was because “Rhapsody” was something of a rush job. None of them had any idea they were creating an epic. It was just a piece for a rather didactic concert of two dozen musical pieces that Whiteman was billing as “An Experiment in Modern Music.” The idea was to show that American jazz, the vibrant new music of the young country, could be just as smart and sophisticated as classical music.

At the time, Gershwin was a hot young star of the Broadway musical set. His “Swanee,” covered by Al Jolson, sold more than a million copies of sheet music. He was working on another musical, “Sweet Little Devil,” in late 1923 and initially turned down Whiteman’s request for a piece to include in his show.

He changed his mind after Whiteman leaked an article to the press saying that Gershwin would indeed perform – there was no way a youngster like him could publicly turn down Whiteman, then the biggest name in dance music.

Gershwin, as he recounted many times later, began composing the piece on a train trip to Boston. He put “Jan. 7” on a piece of sheet music and sketched out a bravura opening – a long, trilling glissando for a clarinet. Then he was off and running, working through several different themes that highlighted different aspects of American music.

But there were only five weeks until the performance and he had his musical to get ready, besides. So he sketched out a 56-page, two-piano short score for a 26-piece orchestra. This was a great start, but there was still work to do. He had a “marked and jazzy” section, for example, that he soon cut.

[image error]

This passage was struck from the final, but Gershwin notes it was to be “Marked & Jazzy.”

So in a cleaned-up, updated version – this time part of it in ink, part in pencil, with much of it filled in by different copyists – he filled out more of the score, but with assignments for only 13 instruments.

He quickly turned this second, cleaner version over to Grofé, the brilliant and innovative composer for Whiteman’s band. Grofé was a key figure in the early days of big band dance music, scoring complicated arrangements between the bass and reed sections that drove the music forward. Classically trained, his tone poem “The Grand Canyon Suite” is still well-regarded, and he went on to have a high-profile career leading his own orchestra and composing music for Hollywood films. (Fun footnote: Parts of his “Grand Canyon” were used in the holiday classic film, “A Christmas Story.”)

Ferde Grofé, Photo: Bain News Service.

So, in the first few weeks of 1924, he didn’t hesitate to use the young composer’s score as a blueprint rather than a Bible. He made changes. He added four violins and two French horns and cut out other instruments.

The result? A piece that would go on to become of the nation’s most cherished musical scores and a long-lasting debate about how much credit Grofé should receive for his contributions. Gershwin, who died of brain cancer at age 38 in 1937, was always clear that he had done the heavy lifting.

“Mr. Grofé made a very fine orchestration from my completed sketch,” he wrote to a music business executive in 1928, “but he certainly had no hand in the composing.”

[image error]

The Library’s leather -bound cover of Gershwin’s manuscript.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers