Library of Congress's Blog, page 51

November 30, 2020

Jason Reynolds: On the (Virtual) School Tour

Jason Reynolds. Photo: Adedeyo Kosokoto.

This is a guest post by Guy Lamolinara, a communications officer in Literary Initiatives.

Kids in 11 schools across the country will soon get a special treat: A visit from Jason Reynolds, the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature.

This being no ordinary time, Jason will visit virtually, but his presence will be no less deeply felt. Jason has a rare gift for connecting with young people and getting them excited about books and reading. This special two-week tour will reach middle and high school students in underserved communities and will complement Jason’s current digital offerings, a prompt-based video series titled “Write. Right. Rite.” and a monthly newsletter all available on Jason’s Library of Congress Resource Guide.

Jason’s National Ambassador platform is called “GRAB THE MIC: Tell Your Story.” He launched this platform because he wants students to embrace and share their stories. Ultimately, Jason sees sharing as a type of empowerment that helps kids become their own ambassadors.

During the first half of December, Jason will meet students from:

W. Eater Junior High School, Rantoul, Illinois

Leland Middle School and Leland High School, Leland, Mississippi

Live Oak Middle School, Denham Springs, Louisiana

Red Cloud Schools, Pine Ridge, South Dakota

Sage Valley Junior High School and Twin Spruce Junior High School, Gillette, Wyoming

Stratton Elementary School and Park Middle School, Beckley, West Virginia

Swansea High Freshman Academy and Swansea High School, Swansea, South Carolina

In each virtual event, Jason will discuss his role and will talk to two “student ambassadors”—each student will ask questions of Jason, and will be asked questions by Jason in return. All participating students will receive a free copy of Look Both Ways: A Tale Told in Ten Blocks and schools across the country may download an educator guide, both courtesy of Simon & Schuster. Each winning school was selected from almost 200 proposals submitted earlier this year.

Jason Reynolds’s goal for his ambassadorship is to visit communities that do not often have the opportunity to host authors for meaningful discussions with young people. Although he must now connect with schools virtually, his goal remains unchanged: “Though we’re living in unprecedented times, times that cause us to pivot and rethink our plans, I’m still just as excited to engage with our young people around stories,” says Reynolds. “If anything, what we’ve learned over the last eight months is that we need each other, and my desire is for that need to be partially satiated with the exchanging of our narratives, even if through a screen. I feel encouraged and am looking forward to ‘hitting the road.’”

Proposals for 2021 GRAB THE MIC tour with Jason Reynolds—currently planned for Spring 2021—are now being accepted via Library of Congress partner, Every Child a Reader.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

November 25, 2020

Mystery Photo Contest: Thanksgiving Edition

Cary O’Dell at the Library’s National Recording Registry runs our Mystery Photo Contest. He recently wrote about readers solving several photos from a September set of pictures. He’s back with another round.

Nothing beats a good Mystery Photo Contest for the holidays and we’re here for you!

After a fantastic round of photo-solving by readers this fall, we were able to identify eight of our final unidentified stars of yesteryear. From the original cache of more than 800 unidentified celebrities in a collection of entertainment industry stills donated to the Library a few years ago, we are now down to 34. Amazing, no?

So here we go again! You know the drill: Guesses and suggestions in the comments, but please check the captions to make sure that we haven’t already ruled it out.

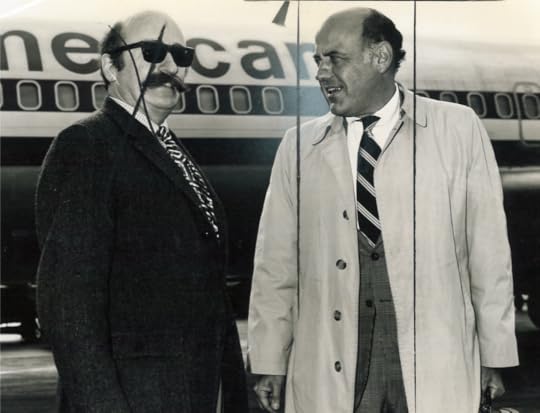

#1. That IS conductor Frederik Prausnitz on the left but we don’t know the man on the right. The photographer tells us that he worked out of out of Camillus, N.Y., and that Prausnitz was associated with the nearby Syracuse Symphony. Those might be clues that help us finally identify mystery man on the right wearing a trench coat and carrying what appears to be a briefcase. (The photo came to us with those editing markings already on it. We certainly wouldn’t be so rude as to X out Mr. Prausnitz.)

#1. That IS conductor Frederik Prausnitz on the left but we don’t know the man on the right. The photographer tells us that he worked out of out of Camillus, N.Y., and that Prausnitz was associated with the nearby Syracuse Symphony. Those might be clues that help us finally identify mystery man on the right wearing a trench coat and carrying what appears to be a briefcase. (The photo came to us with those editing markings already on it. We certainly wouldn’t be so rude as to X out Mr. Prausnitz.)

#2. Of all of mystery photos we’ve sorted through over the years, this is the one that might actually be a stock shot from an ad agency. You know, the generic “happy girl dancing” image that might appear in an advertisement. Then again, our mystery lady might be a budding recording star and this is a back-of-the-album photo. From previous guesses, we can rule out former 1980s pop stars Brenda K. Starr and Perri “Pebbles” Reid.

#2. Of all of mystery photos we’ve sorted through over the years, this is the one that might actually be a stock shot from an ad agency. You know, the generic “happy girl dancing” image that might appear in an advertisement. Then again, our mystery lady might be a budding recording star and this is a back-of-the-album photo. From previous guesses, we can rule out former 1980s pop stars Brenda K. Starr and Perri “Pebbles” Reid.

#3. This is NOT Pan Am founder Juan Trippe, although that is an excellent guess. Though this picture was found in a cache of show biz stills, this unknown gentleman might be connected to travel or shipping in some way considering the map and the photo of ships behind him. A newscaster, maybe?

#3. This is NOT Pan Am founder Juan Trippe, although that is an excellent guess. Though this picture was found in a cache of show biz stills, this unknown gentleman might be connected to travel or shipping in some way considering the map and the photo of ships behind him. A newscaster, maybe?

#4. UPDATE: Alert reader Collin Larsen correctly identified this as former actress Marta Brennan. She appeared as a young actress in “Centennial,” a star-studded 1978 mini-series that featured Raymond Burr, Robert Conrad, Barbara Carrera, Lynn Redgrave and so on. That’s her only credit on the Internet Movie Database. She now edits a film production newsletter and confirmed for us that this publicity photo is indeed her. Thanks, Collin! This one has proved to be very frustrating, as it has generated so many different guesses. Maybe it’s because that cheerful girl-next-door look resembles so many actresses? Bangs notwithstanding, we know that she is NOT: Karen Valentine, Judy Strangis, Joyce McKinney, Sheila White, Glory Annen, Janet Munro, Jody Fair, Janice Nicholls, Barbara Flynn, Lalla Ward, Suzy Mandel or Helen Worth. By the way, as an identifying feature, I’ve always been struck by the small gap between this lady’s two front teeth.

#5. This is, we assume, a silent film actress. Is it Edwina Booth, she of the tragic filming “Trader Horn” in east Africa? Booth was sick when she left the United States, then had a terrible shoot on location, including contracting malaria, suffering from a sunstroke and other ailments. The film was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture in 1931, but she sued the studio, spent six years recovering her health and never returned to prominence. Or perhaps it’s Jeanette Loff, who, after her silent film career, died of ammonia poisoning in 1942 under mysterious circumstances? She was just at 35.

#5. This is, we assume, a silent film actress. Is it Edwina Booth, she of the tragic filming “Trader Horn” in east Africa? Booth was sick when she left the United States, then had a terrible shoot on location, including contracting malaria, suffering from a sunstroke and other ailments. The film was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture in 1931, but she sued the studio, spent six years recovering her health and never returned to prominence. Or perhaps it’s Jeanette Loff, who, after her silent film career, died of ammonia poisoning in 1942 under mysterious circumstances? She was just at 35.

#6. This is NOT Maria Montez, the “Queen of Technicolor” in B movies in the early 1940s. Nor is it from the film “Sinbad the Sailor.” In fact, it might not be from a film at all—note that our heroine seems to be lying on a stage with its curtain visible in the background.

#6. This is NOT Maria Montez, the “Queen of Technicolor” in B movies in the early 1940s. Nor is it from the film “Sinbad the Sailor.” In fact, it might not be from a film at all—note that our heroine seems to be lying on a stage with its curtain visible in the background.

#7. This pictures smacks of being shot at the local mall (sorry, just calling balls and strikes here) so we probably aren’t looking for a national name. I always figured he must be a musician with a local orchestra or something similar — or, of course, not. He might be a Hollywood or New York name with a long list of behind-the-scenes credits. But who is he?

#7. This pictures smacks of being shot at the local mall (sorry, just calling balls and strikes here) so we probably aren’t looking for a national name. I always figured he must be a musician with a local orchestra or something similar — or, of course, not. He might be a Hollywood or New York name with a long list of behind-the-scenes credits. But who is he?

#8. This one is torturous! This duo is hard to identify as they look like every punk/new wave duo that ever plugged in an amp or bought a can of hairspray. In fact, we haven’t even been able to reach an agreement if—in a binary sense–this is two men, two women or one of each. We do know that it is NOT: Wendy & Lisa, T-Rex, Heart, Suicide, The Throbs, The Slits, Scarlet Fantastic, Sparks, Tik and Tok, Alannah Myles, The Motels, the New York Dolls, Christian Death, Love and Rockets, the Jacobites, Sisters of Mercy or Haysi Fantayzee.

#8. This one is torturous! This duo is hard to identify as they look like every punk/new wave duo that ever plugged in an amp or bought a can of hairspray. In fact, we haven’t even been able to reach an agreement if—in a binary sense–this is two men, two women or one of each. We do know that it is NOT: Wendy & Lisa, T-Rex, Heart, Suicide, The Throbs, The Slits, Scarlet Fantastic, Sparks, Tik and Tok, Alannah Myles, The Motels, the New York Dolls, Christian Death, Love and Rockets, the Jacobites, Sisters of Mercy or Haysi Fantayzee.

#9. This pin-up is NOT Kitten Navidad, though many readers who have apparently seen her in those kitschy Russ Myer movies thought so. She could be an actress, singer, a model or all of the above; she’s got the glamour smile and the dimples for show biz.

#9. This pin-up is NOT Kitten Navidad, though many readers who have apparently seen her in those kitschy Russ Myer movies thought so. She could be an actress, singer, a model or all of the above; she’s got the glamour smile and the dimples for show biz.

#10. We go back to an earlier era and different style of mystery guest here. The framing of the shot is straightforward; her posture is the same. There’s no vamp or vixen vibe; it’s a woman nicely dressed wearing white stockings and what might even be sensible shoes. The sepia tone, dress and hairstyle all suggests the 1920s or thereabouts. Could this be vaudeville star Stella Mayhew? Maybe Lillian Shaw, who specialized in risqué vaudeville routines, a la Sophie Tucker?

#10. We go back to an earlier era and different style of mystery guest here. The framing of the shot is straightforward; her posture is the same. There’s no vamp or vixen vibe; it’s a woman nicely dressed wearing white stockings and what might even be sensible shoes. The sepia tone, dress and hairstyle all suggests the 1920s or thereabouts. Could this be vaudeville star Stella Mayhew? Maybe Lillian Shaw, who specialized in risqué vaudeville routines, a la Sophie Tucker?

#11. The artist’s signature on this painting is “Kepler.” It’s not the artist Fred Kepler, we checked that out. But what is his/her first name? And is this work featured in a film or TV show?

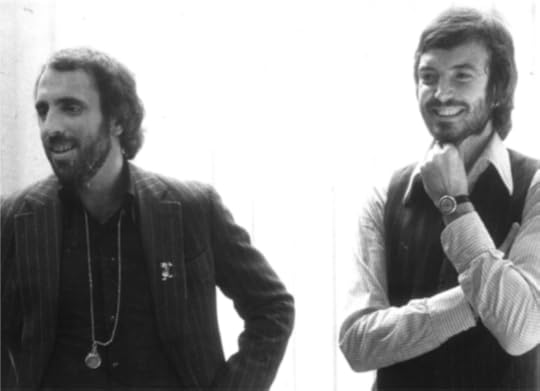

#12. These two guys have us stumped. The man on the right is NOT Richard Chamberlain and the two are NOT Chas & Dave or the Alan Parsons Project or Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager of Studio 54 fame. And, yep, that is a Donald Duck pin on the man’s lapel.

#12. These two guys have us stumped. The man on the right is NOT Richard Chamberlain and the two are NOT Chas & Dave or the Alan Parsons Project or Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager of Studio 54 fame. And, yep, that is a Donald Duck pin on the man’s lapel.

#13. Yes, the only woman at the table is a young Gloria Stuart, the actress who memorably played the late-in-life Rose character in “Titanic,” with Kate Winslet starring as the younger Rose. But, since our hearts must go on: Does anyone recognize any of the men around her?

#14. Hey kids, it’s a Hawaiian luau! But who are the two women and the man enjoying it? This looks too dressy to actually be on the beach, so maybe it’s a p.r. launch for a film, theater production or stage show?

#14. Hey kids, it’s a Hawaiian luau! But who are the two women and the man enjoying it? This looks too dressy to actually be on the beach, so maybe it’s a p.r. launch for a film, theater production or stage show?

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

November 23, 2020

A “Thanksgiving Hymn” for Lincoln

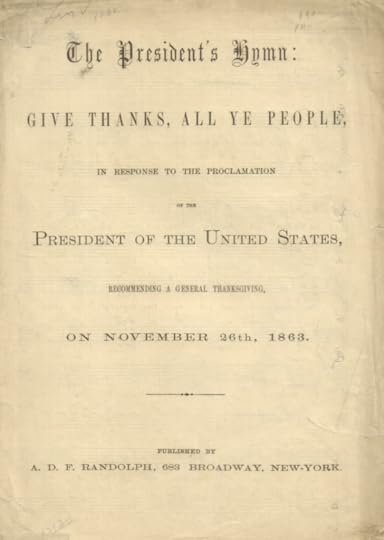

“The President’s Hymn,” William Augustus Muhlenberg. 1864.

This is a guest post by Mark Dimunation, chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

On October 3, 1863, following the hard-fought Union victory at Gettysburg, President Abraham Lincoln asked the nation to commemorate the event in a spirit of gratitude by celebrating November 26, 1863, as an official day of Thanksgiving.

Secretary of State William Seward penned the address for Lincoln. In it, the nation was called upon to set aside the fourth Thursday of November in the years to come as a national holiday. This was in part a gesture back to 17th- and 18th-century America, when days of humility and thanksgiving were announced as a means to unite the population in a moment of gratitude and prayer.

George Washington called for a day of “Public Thanksgiving and Prayer,” when he stepped into his first term as the nation’s first president. The practice fell to the side after Thomas Jefferson took office, as he rejected the overt religious tones of such a proclamation. No further official Thanksgiving announcements were made until Lincoln called upon the nation in 1863.

The Rev. William Augustus Muhlenberg, a prominent Episcopal clergyman, educator, and the founder of St. Luke’s Hospital in New York City, was so taken by Lincoln’s proclamation that he wrote the lyrics for a hymn, “Give Thanks All Ye People” (music by Joseph W. Turner) as a celebration of the moment. The hymn was a metrical version of the President’s address.

In a letter to the editor of the New York Times on November 17, 1863, Henry W. Bellows, an American clergyman and president of the United States Sanitary Commission, revealed the impetus behind Muhlenberg’s hymn: The President’s proclamation “made our ‘Harvest Home’ a National Festival; a significant and blessed augury of that ‘more perfect Union,’ in which, with God’s blessing, the war shall leave us as a people.”

It was only fitting, Bellows suggested, that the hymn be called “The President’s Hymn.”

He wrote: “Solicitous to have the highest authority given to the use of this National Hymn, I obtained the reluctant consent of its writer (author also of the music to which it is set) to ask our Chief Magistrate’s permission to style it ‘The President’s Hymn.’ The Secretary of State, through whom the application was made, telegraphed me a few hours afterwards the President’s leave — in the decisive style which has now become so familiar to our people – ‘Let it be so called.’ May we not hope that millions of our people will, on Nov. 26, be found uniting in this National Psalm of Thanksgiving, and that ‘The President’s Hymn’ will be the household and the Temple song of that solemn and joyful day? It will help to join our hearts as citizens thus to blend our voices as worshippers; and the blessings of Union, Liberty and Peace will sooner descend on a people that can thus unite in its praise and hosannahs.”

“Give thanks, all ye people, give thanks to the Lord,

Alleluias of freedom, with joyful accord,

Let the east and the west, north and south roll along,

Sea, mountain and prairie, one thanksgiving song.”

The hymn did not take hold in the American mind, but Congress officially made Thanksgiving a national holiday in 1870, although the fourth Thursday in November date was not designated. President Franklin D. Roosevelt moved up the date by a week late in the Depression in an attempt to lengthen the Christmas shopping season, but it proved extremely unpopular. Congress passed a bill that officially designated the last Thursday in November as the date in October 1941, and Roosevelt signed it that December. It has been observed on that date ever since.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

November 20, 2020

College Students: Apply Now to be a Library Junior Fellow!

The 2020 class of Junior Fellows.

This is a guest post by the Junior Fellows Program team.

College students! If you’re looking for an excellent, one-of-a-kind virtual internship next summer, you’ll want to apply for the Library’s Junior Fellows Summer Internship Program 2021. But hurry — the applications window closes on midnight on Monday, November 30.

You can check out our 2020 Fellows and what they did last year to get an idea of how your online summer job might work.

What’s this look like? It’s a 10-week paid internship, running from May 24 – July 30, 2021. It’s open to undergraduate and graduate students interested in learning and conducting research at the largest library in the world. For the second year in a row, the internship will be conducted virtually. When you apply, please be sure to list your top three choices.

This year the program will offer 23 projects across many of the Library’s divisions, such as Manuscripts, Preservation Research and Testing, Digital Strategy, the Law Library and many of the regional divisions of world study. During the summer you might work on a project that explores new ways to support digital scholars, develop new preservation techniques or make our collections more accessible. Twice weekly you will have the opportunity to explore a broad spectrum of our operations by participating in professional development opportunities, including virtual tours, lectures and forums.

Your work will be guided by a project mentor (a Library curator or specialist) in your host division. You’ll have the opportunity to explore digital initiatives and increase access to the institution’s unparalleled collections, programs and resources.

Sound interesting? Please fill out the online application right away. If you’ve got questions, please email juniorFellows@loc.gov rather than post them in the comments.

Hope to see you this summer!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

November 19, 2020

Poet Laureate Joy Harjo Gets a Third Term; Launches “Living Nations, Living Words”

This is a guest post by Rob Casper and Anne Holmes of the Library’s Literary Initiatives office.

U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Joy Harjo, the first Native American to serve as the U.S. Poet Laureate, will serve a third term in the office, the Librarian of Congress announced today, making her only the second person in the position’s 77-year history to do so. Harjo will start that third year next September. We’re hoping that health conditions in the country will by then allow her to return to traveling across the nation to read her work and champion poetry.

Today also marks the launch of Harjo’s signature project, “Living Nations, Living Words,” which features 47 contemporary Native poets through a new story map and online audio collection.

“Throughout the pandemic, Joy Harjo has shown how poetry can help steady us and nurture us. I am thankful she is willing to continue this work on behalf of the country,” said Librarian Carla Hayden. “A third term will give Joy the opportunity to develop and extend her signature project.”

When Harjo first accepted the position in April 2019, she talked about wanting to create an online map of living Native poets. She soon met with staff in the Geography and Maps Division, who introduced her to the perfect platform: ArcGIS StoryMaps, an online app geared toward storytelling that the Library uses as an immersive learning tool.

As Joy explored the platform and talked about the possibilities for her project, it became clear that she not only wanted to feature a number of Native poets, but wanted to hear from them, too, reading and discussing their work. She felt strongly that these poets should choose their own poems, while keeping in mind the theme of place and displacement, and the following touchpoints: visibility, persistence, resistance and acknowledgment.

Joy had also spent time the previous summer exploring collections in the Library’s American Folklife Center. When we started discussing the possibility of building a new collection featuring the poems and voices of Native poets, AFC seemed like the perfect home. This new collection was a first for us, and we’re delighted that it features poets such as Louise Erdrich, Natalie Diaz, Ray Young Bear, Craig Santos Perez, Sherwin Bitsui and Layli Long Soldier. The accompanying commentary by the participating poets added ethnographic value to their recordings—a key component of AFC collections.

Map of Native American poets, part of Harjo’s project.

In the months that followed, we worked and dreamed with Harjo and our colleagues in these two divisions to bring “Living Nations, Living Words” to life. In June, we began inviting poets to contribute their poems and voices to the project. In October, we began building the map.

Today, we invite you to dive in and explore all that “Living Nations, Living Words” has to offer. As Harjo writes in the introduction, “There are connections between all of the poets in ‘Living Nations, Living Words’—and connecting influences between these poets and many, many other Native poets who do not appear here, and many, many American and world poets from the present and generations before. As you explore, you too will be connected.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

November 16, 2020

Copyright: Deposits of Gold

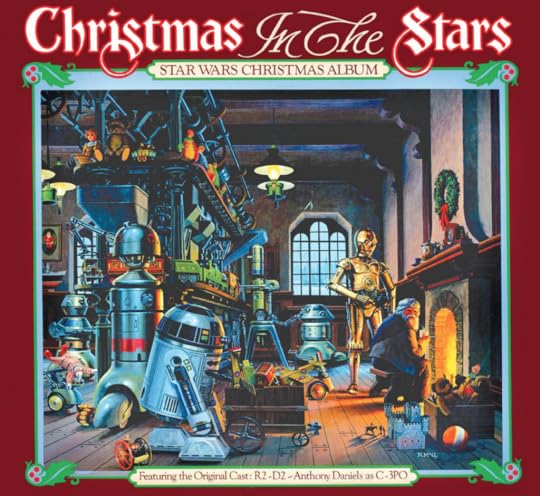

The Star Wars Christmas album, featuring the recording debut of Jon Bon Jovi.

The vast collections of creative works deposited at the Library of Congress for copyright registration over the decades chronicle the artistic genius of generations of Americans — even budding geniuses.

When Paul Simon came to the Library in 2007 to accept its Gershwin Prize for Popular Song, Music Division librarians were able to present him with the original manuscript for the first song he ever wrote, a tune he composed at age 12 or 13 called “The Girl for Me.”

Simon’s dad had written out the music and lyrics on paper and submitted it for copyright registration. The Library stored the submission away for safekeeping — years before Simon composed “The Sound of Silence” and “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” years before anyone could know the historical significance that piece of paper would one day hold.

Over the past 150 years, the Library has preserved millions of such works as submissions for copyright to the U.S. Copyright Office, located in the Library.

Those submissions preserve works everyone knows (Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech) alongside multitudes that went unheard (an unpublished musical version of “The Great Gatsby”) or were heard and forgotten (“Do the Oz,” a song based on the “Hokey Pokey” that John Lennon wrote to raise funds for the defense of Oz magazine in an obscenity trial).

In 1870, Congress passed legislation that transferred the copyright function from federal courts to the Library — a milestone in copyright history and in the development of Library collections.

The law required authors, poets, artists, composers and mapmakers to deposit at the Library two copies of each published work registered for copyright in the U.S. Later, the law also allowed for the submission of some unpublished works.

Portions of the massive collection of copyright deposits eventually were transferred to other Library divisions for preservation — a treasure trove of history that otherwise might be lost.

We know how the march played at Abraham Lincoln’s funeral in 1865 goes because the composer’s daughter submitted the music manuscript, “To the Memory of President Lincoln,” for copyright in 1911.

Copyright deposits capture milestones, even if they aren’t recognized as such until years later.

The Copyright Office holds the unpublished deposit for a 1980 “Star Wars” Christmas album that marks the recording debut of Jon Bon Jovi, who sang lead vocals on “R2-D2 We Wish You a Merry Christmas.” (Sample lyric: “If the snow becomes too deep, just give a little beep. We’ll go there by the fire and warm your little wires.”)

They reveal new dimensions to famous folks — an unpublished composition by a 14-year-old Aaron Copland, for example, or unpublished plays written by Tennessee Williams and Zora Neale Hurston.

Mae West , posing in 1948. Photographer unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Manuscript Division holds 13 such plays by Mae West, the actress and sex symbol whose ability to impart suggestive meaning to any line onscreen is immediately apparent in her writings, too. “The things I can teach you are not in the books,” a seductress slyly tells Professor Thinktank in “Ruby Ring,” a 20-page play West submitted for copyright in 1921.

In 1997, a Library staffer discovered 10 unpublished plays written by Hurston, the African American anthropologist and author who died in obscurity in 1960. She later became celebrated for her novels and work as a folklorist, but few knew of her ambitions as a dramatist until that discovery among copyright deposits nearly four decades later.

Copyright deposits record the history of events that never even happened.

The Music Division holds songs composed for productions that were begun and then called off, including dozens for a live TV musical version of “Hansel and Gretel” and “Rainbow Road to Oz,” a film project that proposed to star the Mouseketeers as characters from the Land of Oz.

They help scholars and artists better understand the works they study and perform.

William Grant Still, the “dean of African American composers,” wrote “Grief” in 1953, and a version published a few years later introduced an error into the final line of vocals. For decades, performers unwittingly sang the piece wrong.

It wasn’t until 2009 that Still’s daughter, feeling something wasn’t quite right, examined the original version submitted for copyright and discovered the mistake — finally, some 50 years on, allowing the piece to be heard as the composer intended.

Copyright deposits are a great resource for the study of early African American music.

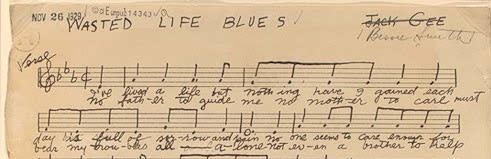

That material preserves songs by well-known figures: the original manuscript of Billy Strayhorn’s “Take the A Train” and Bessie Smith’s manuscript for “Wasted Life Blues,” on which she crossed out her husband’s name as composer and wrote in her own.

Bessie Smith (above), crossed out her husband’s name as the author of “Wasted Life Blues” and wrote in her own. Copyright Division.

But they also are invaluable for preserving works by lesser-known artists, shows such as Henry Creamer and Turner Layton’s “Ebony Nights” (1921) and Louis Douglass and James P. Johnson’s “The Policy Kings” from 1938.

Movie studios tragically threw away historical music scores to save the expense of storage — even the original music for “The Wizard of Oz” didn’t survive. Copyright deposits preserve elements of films and TV shows that otherwise might not exist.

The Music Division holds original scores for “How the Grinch Stole Christmas” and lead sheets to songs — “I’m in the Middle of a Muddle,” “Pretending,” “Raga-Daga-Day” — that didn’t make the cut for Disney’s classic “Cinderella.”

Copyright deposits preserve Elmer Bernstein’s score for “The Ten Commandments,” Jerry Goldsmith’s avant-garde work on “Planet of the Apes” and music Charlie Chaplin composed for his own films.

With the advent of sound technology, Chaplin went back and wrote scores for his silent features. In his 1919 film “Sunnyside,” Chaplin milks a cow directly into his coffee and holds a chicken over a pan to get an egg for breakfast — a scene eventually accompanied by a waltz composed by Chaplin and submitted for copyright in April 1977, eight months before his death.

Pieces of history, preserved by the copyright process for posterity.

Charlie Chaplin. Bain News Service, 1915-1920. Prints and Photographs Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

November 12, 2020

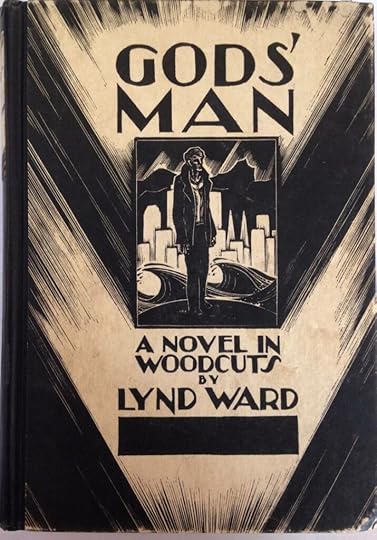

Lynd Ward’s Eerie, Early Graphic Novel, “Gods’ Man”

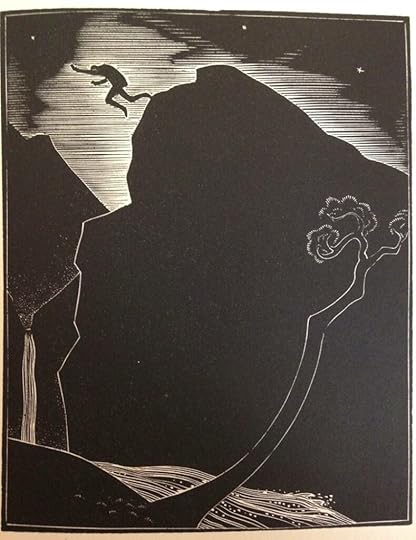

The grinning skull, from “Gods’ Man,” by Lynd Ward. Photo of book page: Mark Dimunation. Rare Book & Special Collections.

Mark Dimunation, chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, wrote about their copy of “Gods’ Man” in an internal memo recently. This is an expanded version of that piece.

We arrive on the doorstep of winter with a gift from the dark, shadowy recesses of the Library: A beautiful, eerily unsettling work of great American significance that, as the artwork above suggests, may leave you with images you cannot easily dismiss.

This is “Gods’ Man,” a 1929 black-and-white wordless novel that tells a Faustian tale of ambition, love, greed and death. It’s by the illustrator and woodcut artist Lynd Ward. It is widely regarded as the first American book of the form and the urtext of the graphic novel. The story is told through 139 uncaptioned woodblock prints, rendered in a dark, foreboding style that mixes Art Deco beauty with the stern lines of German expressionism. It can leave you breathless with its craftsmanship, vision and narrative detail.

The cover of Wards’ groundbreaking wordless novel. Photo: Mark Dimunation. Rare Books and Special Collections.

But “Gods’ Man” and Ward’s five subsequent wordless novels were not regarded as a bold new stroke for literature in their day. They were just Depression-era quirks. They sold moderately well and drew good-but-not-great reviews, and Ward moved on to more profitable lines of work. It was only decades later, after comics had matured from the funny pages into sophisticated, standalone stories called graphic novels, that his influence was fully realized.

“[Ward was] the father of pure ultimate visual,” the late Will Eisner once said, a remarkable testament considering that Eisner is one of the most influential comic artists in the second half of the 20th century and the namesake for the Eisner Awards, the comics equivalent of the Academy Awards. “I’ve tried to reach that same mountaintop and have never been able to do it.”

“Way ahead of his time, a visionary in understanding the importance of the book as an object, as a container of a kind of content,” said Art Spiegelman, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of “Maus,” the 1986 graphic novel about the Holocaust that has itself become an iconic narrative of the form.

The Library’s first-edition copy of “Gods’ Man” is part of our collection of hundreds of pieces of Ward’s work, from original prints and woodblocks to the woodworking tools he used in his craft. The collection is housed in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division and the Prints and Photographs Division. Ward died at 80 at his home in Reston, Virginia, in 1985. His collection was given to the Library in 2003 by Robin Ward Savage, his daughter. (Georgetown University has the most significant holdings of his work.)

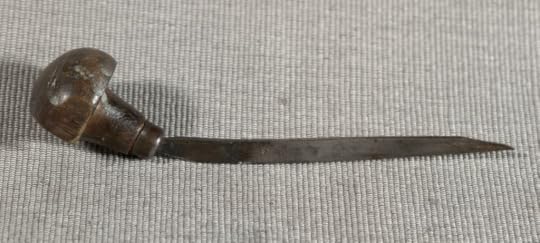

A burin, one of Ward’s many woodworking tools in the Library’s collections. Prints and Photographs Division.

Ward was born in 1905 in Chicago, survived a bout of tuberculosis and quickly developed a talent for drawing. He was raised in a progressive, forward-thinking family that soon moved to the East Coast. His father, Harry K. Ward, was a British-born minister with a strong social reform streak, and Ward would hew to socialist ideals all his life.

He earned a fine arts degree from Teachers College at Columbia University in New York and married fellow student May McNeer, who obtained her degree from the Columbia School of Journalism. The pair would work together, often collaborating on books, for the rest of their lives.

They honeymooned in Europe and stayed a year in Leipzig, Germany, where Ward studied illustration. There, his encounter with German expressionism in general, and with the Flemish artist Frans Masereel’s “The Sun” in particular, greatly influenced his thinking. “The Sun” was a wordless novel, a form then unknown in the United States.

The young couple returned to the U.S. in 1927. Ward put together “Gods’ Man” in 1929, when he was just 24 years old. (The plural “Gods” in the title was intentional, invoking a world of many gods, not just one.)

In the story, a naïve artist signs a contract with a masked stranger in exchange for a brush. The brush propels him into fame and he soon finds himself in a bloated life of wealth and excess. Disillusioned and enraged, he strikes back, only to awaken to find himself in jail. He escapes, chased by a vengeful mob, who drive him over a cliff. Badly injured, he is discovered by a simple woman who lives in the woods. They marry and have a child.

But as fate would have it, the stranger returns and asks him to paint a portrait. When the stranger removes his mask, the visage is so terrifying that the artist flees and falls to his death at the cliff – the stranger with the skull-like head has exacted his contracted price for the brush.

A woodcut illustration from “Gods’ Man.” Photo of book page: Mark Dimunation. Rare Book and Special Collections.

The images were striking and, over the next decade while working as an illustrator, Ward created five more wordless books, each concerned with major issues such as fascism, the slave trade, the Depression, the plight of workers and so on. There was “Mad Man’s Drum,” “Wild Pilgrimage,” “Prelude to a Million Years,” “Song Without Words” and, finally, his masterpiece of the form, “Vertigo,” in 1937.

“Let’s Read” Book Week Poster, 1959. Lynd Ward. Prints and Photographs Division.

There was no real market for the books, though, and Ward continued his work as a high-profile artist, illustrator, painter and author. He contributed artwork to more than 200 books for children, juveniles and adults. He did the artwork for a book of poetry by William Faulkner and a hugely influential illustration of Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein.” The first children’s book he both wrote and illustrated, “The Biggest Bear,” won the Caldecott Medal in 1953. He illustrated classic works for the Limited Editions Club.

Over time, artists in other fields found his work and were dazzled. Allen Ginsberg used a section of “Wild Pilgrimage” as the inspiration for a section of his poem, “Howl.”

And Guillermo del Toro, the Academy Award-winning director of such films as “The Shape of Water” and “Pan’s Labyrinth,” lists Ward as one of his key influences. In a 2015 tweet, the Mexican director summed up Ward’s worldwide influence in a nutshell: “LYND WARD: American, his ‘wordless novels’ combine a modern graphic approach with Old Testament damnation. Fearsome.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

November 10, 2020

The Original Lady Liberty

The picture of the model of the Statue of Liberty that Bartholdi submitted for copyright. Copyright Division.

This is a guest post by Alison M. Hall, writer and editor in the Copyright Division. It also appears in the Sept.-Oct. issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Of the tens of millions of creative works registered with the Copyright Office, the Statue of Liberty is one of the biggest and most famous.

French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi registered his “Statue of American Independence” on Aug. 31, 1876, submitting two photos of a model of the statue as the deposit copies. The first image shows just the model. The second is a rendering of how the statue would appear against the New York skyline on the pedestal. The pedestal also is registered with the office with architect Richard M. Hart listed as the author.

This second image has great significance because it shows a very early version of the statue that most people today would not recognize.

In the original design, the Statue of Liberty is shown holding a broken chain and shackle in her left hand, representing freedom newly achieved. Bartholdi later made a major change to his design by placing the chain and shackle, symbolically broken by Liberty, at her feet. He then positioned the familiar tablet, inscribed “July IV, MDCCLXXVI” (July 4, 1776), in her left hand.

In the decade before the statue was assembled in New York Harbor, newspapers and magazines popularized images of it, and memorabilia proliferated. New York publisher Root and Tinker registered a color lithograph of the statue in 1883, thought to have been commissioned to raise funds to build the pedestal. The next year, the publisher registered a reissue of the same lithograph with “Low’s Jersey Lily for the Handkerchief” imprinted on the statue’s base.

The copyright on the original Statue of Liberty sculpture has expired, which means it is now in the public domain. Creators are free to use it in any way in their works.

Copyright application of Statue of Liberty, set in New York Harbor. Copyright Division.

November 3, 2020

Election Day: Vote. That’s It.

Vote. Today. That’s all.

Works Progress Administration poster urging people to vote during World War II. 1943. Prints and Photographs Division.

November 2, 2020

Jason Reynolds: Grab the Mic November Newsletter

This is a guest post by Jason Reynolds, the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature.

Last night I had a dream I went to vote, but all the names on the ballot were of kids I knew. Some really young, and some closer to grown, but all part of the fabric we refer to as youth. I was so excited, overwhelmed with joy to blacken a bubble for a young person to run our country. Finally. Now, some of you might be saying to yourselves, “Man, I couldn’t be the leader of America. At least, not yet.”

And to you, I say, of course you could! You all could. Here’s why:

IMAGINATION: You still actually believe there are true ways and, more importantly, new ways to change the world. That there are things that could be invented to shift the way we live. It doesn’t matter how strange and far-reaching it is, or even how frustrating it makes older people feel: You aren’t afraid to let your imaginations run wild. And right now, we need that.

FAIRNESS: Once I was in an interview with a young person who expressed how absurd he thought racism was. And he felt this way about all the isms. None of them made sense to him.

I asked him, “How do you think we fix it?”

He thought for a moment, then responded. “People just gotta stop being mean.”

Such a simple statement (that even I, in this moment, want to dismiss as naïve) holds such profundity. Kindness. What if we could actually be kind? It’s easier to do it. Easier on our minds and bodies. It’s healthier for us. And this young man said it with such resolve. Such certainty. It was as broad and as big as his imagination was; he couldn’t imagine a reason for prejudice and hatred. And neither can I. And I’d like to believe most of us feel this way.

COLLABORATION: In my generation, and all the generations before me, there’s been a belief that a single person should sit in the top seat. Of everything. The gold medalist. The first placer. The winner. The boss. And everyone else is pretty much … everyone else. It’s a competitive energy I honestly think is healthy for many things. It teaches persistence and helps to structure life in a (sort of) functional way.

Your generation is a little different. You play together, and you celebrate together for playing together. We tease you about the whole “participation trophy” thing, because our fear is that you won’t have enough grit to compete with the world. But … I wonder if there’s something to be said for the fact that because you all push back against the single winner, you can see value in all your teammates. You can more easily acknowledge the strengths of each individual and how they all have a part to play. Which means as president you’d truly understand the power of a diverse and dynamic cabinet. As a matter of fact, maybe you all would make it so that the presidential seat was a bench shared by a few people at a time. Each important for different reasons. The presidents.

TECHNOLOGY: You all understand it better than the rest of us, which means you’d be able to use it better than the rest of us. The coolest part about it is you—through social media, video games and YouTube—have developed relationships with young folks from all over the world who are going to someday lead their countries. And it’s harder to go to war with whom you used to talk to everyday through a headset. Whom you partnered with in zombie killings. Whose cultural differences you’ve learned about through YouTube and whose cultural similarities you’ve celebrated through TikTok. Not to mention, it’s harder to hate people you can call by name.

FUN: It’s still a priority. You understand why it’s important to have it, and you will do anything for it not to be taken from you. And I like that about you. So maybe you’d invent a few new holidays. Like Block Party Day, where the whole country has to throw block parties, and we all have to get to know our neighbors. That would be cool. And maybe the most patriotic thing EVER. I’m sure you all could come up with something better than that, but … yeah.

Of course there are other things you have to know as far as policy and law and blah blah blah, but all that can be learned. It’s much, much harder to learn imagination, fairness, collaboration, technology and fun. But more than anything, what you all have is courage. And it’s that courage I believe in most.

I would tell you that you’d have my vote—like in my dream—but the truth is, you’ve had it for a long time now. Whether your name is on the ballot or not, just know you already are the leaders of the free world. I’m just trying to make sure I stay close to you, waiting for the day you create the world of the free leaders.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers