Library of Congress's Blog, page 38

December 14, 2021

“Return of the Jedi,” Mark Hamill and the 2021 National Film Registry

The National Film Registry’s 2021 class is the most diverse in the program’s 33-year history, including blockbusters such as “Return of the Jedi,” “Selena” and “The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring,” but also the ’70s midnight-movie favorite “Pink Flamingos” and a 1926 film featuring Black pilots in the daring new world of aviation, “The Flying Ace.”

The 2021 selections, announced today, include movies dating back nearly 120 years and represent the work of Hollywood studios, independent filmmakers, documentarians, women directors, filmmakers of color, students and the silent era. Most pointedly, the inductees also include a trio of documentaries that addressed murderous violence against Blacks, Asians and Latinos, respectively, in “The Murder of Fred Hampton,” Who Killed Vincent Chin?” and “Requiem-29.”

“The National Film Registry will preserve our cinematic heritage, and we are proud to add 25 more films this year,” said Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden. “The Library of Congress will work with our partners in the film community to ensure these films are preserved for generations to come.”

Mark Hamill as Luke Skywalker in a scene from “Return of the Jedi.” Photo: Lucasfilm/Walt Disney Company.

Mark Hamill, who plays Luke Skywalker in the “Star Wars” series, was one of a dozen key players in this year’s class of films to join the Library for interviews about their work. He emphasized that at the time “Star Wars” made its 1977 debut, it was largely understood to be for children.

“It had a princess, it had a pirate, it had a wizard, a farm boy, a big bad boogie-man,” he said of the original “Star Wars” trilogy, of which “Return of the Jedi” was the third installment. “It was clearly a fairy tale, but just put in the context of, you know, a Flash Gordon, Buck Rogers-type space opera, serial play.”

One of the reasons the films have gone on to make such a lasting cultural impact, he said, is because they were so optimistic during an period of national disillusionment.

“It was an era of great cynicism in film,” he said. “Post-Vietnam, post-Watergate, action films usually had revenge and anti-heroes (as) the order of the day … so for George (Lucas, the films’ creator) to make something like this, he almost had to set it in a galaxy far, far away and put it forward as a fantasy, because you couldn’t tell a contemporary story with that sense of optimism. It just seemed too corny.”

This year’s selections bring the number of films in the registry to 825, representing a miniscule portion of the 1.7 million films in the Library’s collections. The list is chosen by the National Film Preservation Board and the Librarian of Congress, selecting films that were influential and important to the history of film and American society. The films must be at least 10 years old to be considered. The public can nominate films, but the final selections are not a popularity contest and they are not necessarily an endorsement of the film itself.

Baltimore’s iconic, often cheerfully outrageous director John Waters made his first appearance on the list this year with 1972’s “Pink Flamingos,” which has the subtitle, “An Exercise in Bad Taste.” Making an underground icon out of Divine, its drag queen star, the film played for years on the midnight movie circuit. Waters’ father loaned him the money to make the film but refused to see it.

“The National Film Registry preserves films that are, well, remembered, loved, hated or whatever caused people to continue to talk about them for a long time,” he said in an interview with the Library, “and I am thrilled to be on the list.”

Actress Liv Tyler stars in “Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring.” Photo: Warner Bros.

The list this year was typically eclectic. The Pixar love story between two robots, “WALL-E,” made the cut, as did the Talking Heads, with their 1983 concert film “Stop Making Sense.” “Sounder,” a 1972 film about a Black family persevering through 1930s Louisiana poverty and racism, was admitted, thus including actress Cicely Tyson’s iconic run across a field to meet her husband returning home.

Alfred Hitchcock’s “Strangers on a Train” from 1951 was selected, joining a host of his other films on the list. The 1963 horror/thriller, “Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?” that featured Hollywood icons Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, was listed, as was the ’80s campy teen horror romp, “A Nightmare on Elm Street.”

Robert Altman’s 1973 “The Long Goodbye” saw iconic detective Philip Marlowe in a hippie-filled Los Angeles, stumbling through a murder mystery. Elliot Gould’s mumbling portrayal of the detective was worlds apart from Humphrey Bogart’s classic turn as Marlowe in “The Big Sleep” a generation earlier, but found a spot in the registry for its unconventional, genre-bending take on the hard-boiled private eye motif.

“Selena,” the 1997 biographical film of Tejana star Selena Quintanilla-Pérez, starred Jennifer Lopez in her first major movie role. Directed by Gregory Nava, it told the story of the young singer’s rise to fame and her tragic death at 23 when she was shot to death by the head of her fan club after a dispute. Selena’s life, music and the film became touchstones in Latin American culture, and her infectious appeal crossed over to audiences of all kinds.

Edward James Olmos in “Selena.” Photo: Warner Bros.

Edward James Olmos, who played Abraham, the father and manager of the family band, said the movie stands out as a universal family story that happens to be about Mexican-Americans along the Texas-Mexico border.

“It will stand the test of time,” Olmos told the Library. “(It’s) a masterpiece because it allows people to learn about themselves by watching other peoples’ culture.”

Two more silent films from the early 20th century portray Black Americans without the degrading stereotypes common to the era. “The Flying Ace,” from 1926, is a straightforward romance. It was made by the Norman Film Manufacturing Company of Jacksonville, Florida, an important producer of “race films” — movies made specifically for Black audiences.

Although owned by Richard Norman, a white man, the studio’s films tended to portray a world in which whites, and thus racism, was absent.

‘The Flying Ace’ is a really special film because it represents Black technical expertise and bravery,” said Jacqueline Stewart, chair of the NFPB and chief artistic and programming officer at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. “It has been said that future Tuskegee Airmen were inspired when they saw this film in their youth.”

Turner Classic Movies (TCM) will host a television special Friday, Dec. 17, starting at 8 p.m. ET to screen a selection of motion pictures named to the registry this year. Stewart will host Hayden in discussing the films. Also, some titles from the NFR are freely available online in the National Screening Room. You can Follow the conversation about the 2021 National Film Registry on Twitter and Instagram at @librarycongress and #NatFilmRegistry.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

December 10, 2021

Football: Bowl Season, the NFL and the Galloping Ghost

Red Grange turns the corner in the 1925 Illinois vs Michigan game. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Susan Reyburn is a writer-editor in the Publishing Office. She is the author of “Football Nation.”

As college football bowl games are about to get underway, with the NFL playoffs starting in a a few weeks, the specter of Red Grange — the Galloping Ghost — looms above the sport’s history, a legend of days gone by. Grange starred for the University of Illinois in the mid-1920s and brought respectability to the sketchy professional sport. He lives on in many ways, but vividly so in photographs from the Library’s collections. You can find them in our Free to Use and Reuse collections, which are copyright-free and are yours to use as you like.

During the Golden Age of Sports, baseball, boxing, horse racing and college football reigned supreme, and Grange, whose shifty moves left would-be tacklers holding nothing but air as he vanished into the end zone, was a household name with the likes of Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey and Man o’ War. If anyone could compel college football fans to give the precarious National Football League a second look, it was the flame-haired Grange. Despite his fame, he was a relentlessly humble man from a modest background — he delivered ice to put himself through college — but whose on-field exploits made him an icon.

In the late fall, especially after baseball season, college football teams dominated the sports pages and drew huge crowds. But at the professional level, the nascent NFL (founded in 1920) struggled to sign college stars, fielded teams that regularly folded and was regarded by sportsmen as disorganized, if not a bit shady.

When Grange signed with the Chicago Bears in 1925 and played his first pro game just five days after his last collegiate contest, those closest to him objected.

“My [college] coach, Bob Zuppke, didn’t talk to me for four years,” Grange later said. “My father wasn’t happy about it. All of my friends looked upon me as if I was a traitor or something, as if I had done something terrible.”

Grange turned out to be exactly what the NFL needed and wanted: He filled stadiums, gave the pro game a sense of legitimacy and showed that with the right personnel in place, the league could be a profitable venture. As the first vital link between the college and pro games, Grange has a place in football history like no other.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

December 7, 2021

Collecting the Globe: The Library Abroad

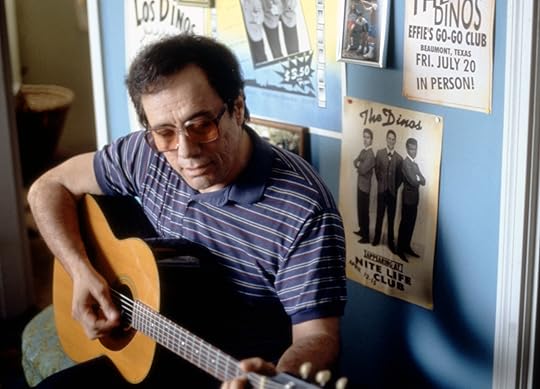

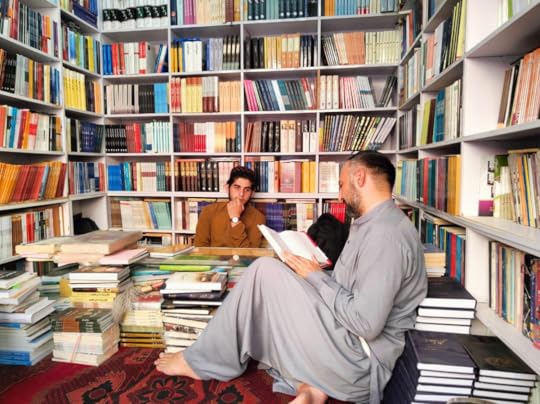

Acquisitions librarian Abdus Salam (right) selects titles from a local bookshop in Peshawar, Pakistan.

Collecting at the Library of Congress literally never stops.

The massive collections of the world’s largest library are the product, in part, of a staff that acquires material around the world, around the clock.

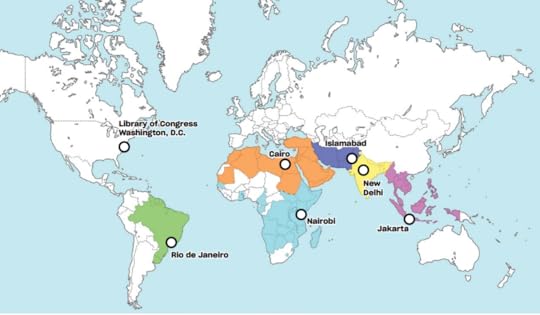

To facilitate its acquisitions work, the Library operates six field offices abroad, stationed across 11 time zones from South America to Southeast Asia.

At any given moment somewhere on the globe — perhaps in Rio, maybe in New Delhi — an employee is acquiring an item to add to the more than 171 million others already in the Library’s collections.

They do so in the face of all manner of challenges: everyday hassles like bureaucratic red tape and unreliable transportation and extraordinary events such as violent social unrest, coups or natural disasters.

The hard-to-find material these offices acquire helps provide Congress, analysts and scholars critical information they need to do their work, today and in the decades ahead. Their mission is unique: The Library of Congress is the only library in the world that operates such a network abroad.

“We are at the forefront of preserving today’s scholarly and cultural output for future access in one shape or form for the generations to come,” said William Kopycki, who for 12 years has served as field director for the Cairo office and temporarily also oversees the Nairobi office. “There is no other institution operating on the scale that the Library does, and that is what makes it the world’s greatest library and a name familiar to all people.”

In the early 1960s, the Library established nearly two dozen field offices around the world — a recognition of the importance that developing regions would play in post-World War II affairs and of the need to better understand these places.

Six of those offices still exist today, set in cities across South America, Africa and Central and Southeast Asia: Rio, Cairo, Nairobi, Islamabad, New Delhi and Jakarta.

These offices confront significant challenges in carrying out their mission.

They cover vast geographic areas, deal with an enormous variety of languages, rely on underdeveloped infrastructure, negotiate bureaucratic processes across dozens of countries and even persevere through natural disasters — in 2015, the Kathmandu suboffice survived a magnitude 7.8 earthquake.

The employees there, at times, face conditions that make just getting to work dangerous.

Massive, violent protests in 2011 and 2013 forced the temporary closure of the Cairo office (located in the U.S. Embassy) and the evacuation of its director from Egypt. In 2012, protestors targeted the embassy and actually came over its walls; the Library’s staff was sent home just an hour beforehand. Pakistan is so risky for Americans that the director of the Islamabad office oversees its operations from neighboring India.

The Library’s offices around the globe.

Oppressive governments pose another challenge.

In some cases, Library staffers have been detained and questioned by authorities. In the past year, the Kuala Lumpur suboffice went to great lengths to get books the government had banned. In some places, suppliers may face difficulties if it’s known that they are acquiring for a “foreign entity”; suppliers sometimes risk their livelihoods, and in some cases their lives, for performing work for the Library.

But the offices persevere, no matter the circumstances — even through coups.

“Coups, whether in Myanmar or another country at a different time, do not stop our staff from seeking to find library resources that make our collections the best in the world,” said Carol Mitchell, who serves as the field director of the Jakarta office and previously held the same position at the Islamabad office. “When there is a regime change — whether Suharto or the next regime change — our staff with their incredible intellectual curiosity and contacts developed over decades will help the Library document those changes.”

Despite the challenges, the overseas offices manage to collect a huge range and volume of material — in fiscal 2020, over 179,000 newspapers, magazines, government documents, academic journals, maps, books and other items that represented about 120 languages and 77 countries and jurisdictions.

As one might imagine, such work gets complicated.

Each office is responsible for a group of countries in its region — the Nairobi office alone covers 30 countries and jurisdictions in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Jakarta office, which covers Southeast Asia, processed material in 43 languages in fiscal 2020: English, Malay, Chinese, Tamil, Tetum, Portuguese, Indonesian, Filipino, Thai, Burmese, Khmer, Vietnamese and Lao in addition to many subnational or minority languages. The two dozen staffers in Islamabad collect in three countries that speak a combined 19 different languages.

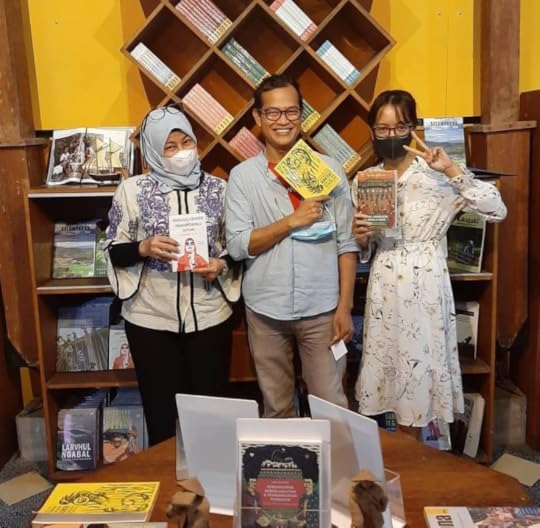

Ade Farida (left), head of acquisitions for the Jakarta Office, meets with representatives of Insist Press Book Stores.

Such an effort requires knowledgeable people at the source, wherever that may be.

Each office is led by an American field director and staffed by Library employees recruited from the local populations — 212 locals across the six offices.

They serve as librarians, linguists, accountants, administrators, IT specialists, preservationists and shipping experts and use many of the same tools as their Capitol Hill counterparts — they perform, for example, real-time cataloging work in the Integrated Library System. In fiscal 2020, the offices created or upgraded nearly 31,000 bibliographic records.

Their knowledge and skill is the key to accomplishing work that requires negotiating so many different languages and cultures. They know what material to get and where to get it, how to navigate cultural nuances and often-tricky political terrain.

To gather material, field office staffs establish relationships with commercial vendors, who regularly acquire material on their behalf. They also work with individuals to find hard-to-get items — such as academic journals and government publications — not readily available in the marketplace.

They also make acquisition trips into the field: a literary festival in Singapore, say, or a local market six hours south of Yangon to get books in the Mon language.

For the offices, these trips are among the most rewarding and challenging work they do.

“Such acquisition trips are important so we can see for ourselves what the state of publishing in a given country is, make connections and contacts with government and other persons who can help facilitate our work, meet with our vendor or representative and otherwise get a front-line view of things,” Kopycki said. “The book publishing industry and distribution in most of our countries is still in dire need of development and modernization, and even if there is good distribution of books within one country, it does not mean that that distribution extends outside its borders.”

The offices select material in collaboration with collections divisions on Capitol Hill, choosing works for the importance of the subject matter, the quality of scholarship and the extent to which they add to the knowledge of a topic.

All that collecting requires a lot of something else: shipping, which sounds simple but often is anything but. Shipping out of country may require navigating a gantlet of bureaucracy: export permits, reviews by censors, payment of taxes.

Then there are the sheer logistics of moving large quantities of items from one far-away place to another.

Books printed in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, must be moved to the Library’s representative in Riyadh, where they are combined with other material and shipped to Cairo. At the Cairo airport, they must be cleared and moved to the Library’s offices at the U.S. Embassy. From there, staffers process the materials and then, after a sufficient quantity is ready, send them off to Washington.

The work of these offices benefits more than just the patrons of the Library of Congress; employees there, in effect, serve as the eyes and ears for other libraries via the Cooperative Acquisitions Program.

Through the program, the overseas offices provide material to 80 institutions in the U.S. and 26 in other countries. Those resources allow analysts and scholars everywhere to gain new perspective on the world — and will allow future generations of scholars to do the same.

“It is not just the Library’s collections that make what we do unique,” Mitchell said. “It is the concept behind those collections that is equally important. That concept remains. It is important that we as global citizens have the capacity to learn and understand.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

December 1, 2021

Maps: A 17th-Century Korean View of the World

Tae Choson Chido, made circa 1874. Artist unknown. Geography and Map Division.

This is a guest post by Ryan Moore, a senior cataloging specialist in the Geography and Map Division. It first ran in the Library of Congress Magazine May-June 2021 issue.

Ch’onhado is a type of Korean quasi-cosmographical depiction that means “map of the world beneath the heavens.”

Koreans developed this view in the 17th century, and it remained popular until the 19th century. Scholars debate its origins but agree that the perspective is uniquely Korean. It exists in many iterations and often was included in atlases.

Sino-centricity is an essential element of the Cho’nhado.

In the Tae Choson Chido, above, China is front and center, shown as a red circle with a yellow interior. Korea — known as Choson — is a yellowed-bordered rectangle with a red interior. To its right is Japan, pictured as a yellow rectangle.

The proximity of these lands is relatively correct. The surrounding rings of land and sea, however, represent both real and mythological peoples and places, whose source was primarily classical Chinese literature.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

November 29, 2021

Sondheim at the Library: A Friendship with “Steve”

Stephen Sondheim in New York, 1972. Photo: Bernard Gotfryd. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post Mark Eden Horowitz, a senior music specialist in the Music Division.

Musical theater reached its apotheosis in the work of Stephen Sondheim. His passing last week at the age of 91 leaves a void that can never be filled.

It is perhaps unfair to make the death of such an important and iconic figure into something personal, but I think that’s part of what makes Sondheim and his work so extraordinary. For many of us, his work became something deeply personal. His songs gave voice to thoughts and feelings we often didn’t have the words to express. He accomplished what one hopes for in most works of art—to connect us to our humanity, to help us realize we aren’t alone. And to many of us who knew him personally, we were blessed by generous and honest advice and thoughtful kindnesses. He was an exemplar for leading a good and meaningful life.

In my case, I owe him my entire career. I grew up as a fan of musicals but thought of them as entertainments. When Sondheim’s work began to inculcate itself into my psyche as a teenager, musicals suddenly became richer, more meaningful and important. I had found an art form to which I could dedicate my life. And I’ve endeavored to do so.

I first met Steve—as he insisted on being called—in January of 1980 when I was a senior in college. We next met in December 1989, when I was working on a production of “Merrily We Roll Along” at Arena Stage here in Washington. By 1993, I was working in the Music Division of the Library and learned that he would be visiting the area. I invited him to the Library for a show-and-tell of some of the choice items in our collections. He accepted.

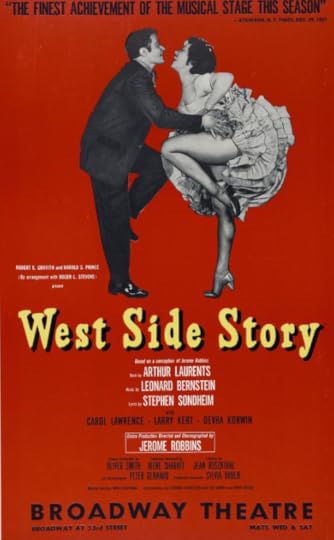

Some of the items, as I recall, were directly related to him, such as lyric manuscripts by his mentor, ; original music manuscripts by Richard Rodgers for “Do I Hear a Waltz?” for which he had written the lyrics; and the letter he wrote to Leonard Bernstein on the opening night of their show, “West Side Story.”

1958 poster for “West Side Story.” Prints and Photographs Division.

Rounding out the display were music manuscripts by several of his favorite classical composers, such as Brahms, Ravel, Rachmaninoff, Bartok and Stravinsky. But the moment that’s seared into my memory is when I showed him Gershwin’s manuscript for “Porgy and Bess” and he began to cry.

Afterward, we discussed the possibility of his papers ultimately coming to the Library. We arranged for me to visit his home and look through his papers, so I could guide him in exactly what we would be interested in. Not long after that visit, tragedy struck: His home caught fire.

It started in the second-floor office of his brownstone. Steve kept his manuscripts in a closet off that office—paper manuscripts in cardboard boxes on wooden shelves. After the fire, he moved to temporary digs for over a year while his house was repaired and remodeled. I returned to the house in 1997. In the meantime, a cinderblock vault had been built in the basement to house his manuscripts. They were still in the same cardboard boxes. When I took boxes that had been on the bottom shelf of the old closet and lifted the manuscripts out of them there were dark singe marks outlining where the music lay in the boxes – probably seconds from going up in flames. It is the one time in my life I believe I have witnessed a true miracle.

That 1997 visit was to conduct three days of videotaped interviews to serve as a complementary crib to his manuscripts. My goal was to clarify markings and try to anticipate the questions of scholars and researchers who would come to examine his manuscripts at the Library. As it happened, the interviews became far more wide-ranging than I expected, and he agreed that they could be published. “Sondheim on Music” is now in its third edition.

In 2000, the Library produced a concert in honor of Steve’s 70th birthday. He and I discussed several possibilities about what the concert’s structure and content might be. He quickly settled on two notions—the evening would begin with a concert version of his obscure musical version of Aristophanes’ “The Frogs” (which had had its premiere in and around a swimming pool at Yale in 1974; both Sigourney Weaver and Meryl Streep were students in the cast). “The Frogs” would be newly orchestrated – by Jonathan Tunick.

This would be followed by a section he titled: “Songs I Wish I’d Written (At Least in Part).” This excited him in particular. He loved the notion of being able to share his enthusiasms and introduce people to a raft of songs they may not know or would be surprised to learn he held in such high esteem. The “(At Least in Part)” was important, because he wanted to make clear that, one, these songs were not a complete list; and two, it might be just one aspect of a song that made it a favorite.

Steve began sending me faxes as songs occurred to him; the final compilation totaled 55 songs. There were five each by Harold Arlen and Cy Coleman; four by Hugh Martin; and three each by Irving Berlin, Jerry Bock, Cole Porter, and Arthur Schwartz. The most contemporary song was Adam Guettel’s “The Riddle Song” from “Floyd Collins” (1994); there was an art song by Aaron Copland, “The Golden Willow Tree”; and a Brazilian folk song, “Bambalelê.”

But I think the most surprising numbers were “Hard Hearted Hannah (The Vamp of Savannah)” and “Waiting for the Robert E. Lee.” Sondheim selected 15 songs to be performed in the concert and, as I recall, the order in which they would be performed. The cast included Nathan Lane, Audra McDonald, Marin Mazzie, and Brian Stokes Mitchell.

I got what I thought was a great idea: I would contact all 15 living songwriters on Sondheim’s list and ask them to write something about Steve for the program. All agreed. Tunick and music director Paul Gemignani asked to contribute as well. The day of the concert, I presented Steve with the program and with, I’m afraid, a bit of a Cheshire Cat grin, mentioned that he might want to look at the things written by the living songwriters. His eyes lit up, and then he began reading them and they dimmed. He had hoped they would write about their own songs and was disappointed that they were accolades to him. This tells you a lot about Stephen Sondheim.

Steve’s relationship with the Library was enduring. He helped us acquire at least two collections from his collaborators—producer/director Hal Prince, and librettist/director Arthur Laurents. He also recommended the Library to others.

One of my last emails with Steve was just last month. He blurbed a book I’d compiled and edited of Oscar Hammerstein correspondence, due out next year. It reads:

What a generous man Oscar was. To write so many letters that actually went into detail about the art and the craft (and life itself) was a time-consuming job. Reading them makes me feel proud and privileged to have known him. And sad that he isn’t around. – Stephen Sondheim

I echo that sentiment now: What a generous man Steve was, in many more ways that I have space to recount here. I feel proud and privileged to have known him. And sad that he isn’t around. And I’d like to think that he and Oscar are now reunited.

Sondheim’s letter to Leonard Bernstein, upon the opening of their “West Side Story.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

November 24, 2021

Researcher Stories: Civil War Photographs, “Chlorophyll Prints” and Robert Schultz

One of Robert Schultz’s chlorophyll print process images, made from a Civil War photograph of an unidentified Union soldier and his daughter. Photo: Prints and Photographs Division.

For years, artist Robert Schultz has made creative reuse of historical Civil War-era images, developing photographs from the Library’s Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Portraits in the flesh of tree and plant leaves found on former battlefields. In turn, the Library has acquired some of his art.

Tell us about your background.

I grew up and went to college in Iowa, then did graduate degrees in creative writing and literature at Cornell University. I taught at Cornell; the University of Virginia; my alma mater, Luther College; and Roanoke College, where I served as the John P. Fishwick Professor of English until my retirement from teaching in 2018. Since then, I’ve worked full time as a writer and artist.

Over the years, I have published seven books — poetry, a novel, biography, memoir — but my work in the visual arts is a fairly recent development. Especially since my retirement from teaching, I have begun to make and exhibit work, most of which is done in photographic “alternative” processes — camera-less work in the chlorophyll print process and creative uses of a scanner.

How did you come to use leaves in your art?

I learned the chlorophyll print process from its modern originator, Binh Danh. I first saw his work in an exhibition that traveled to Roanoke, Virginia — big tropical leaves with portraits of Khmer Rouge victims in them and smaller leaves with images out of the Vietnam-U.S. war.

They floored me, and I started writing poems in response. When I contacted Binh with questions, he responded generously, and we struck up a correspondence. Then, when Hollins University brought him to Roanoke for a residency, he and I met and began to travel to Civil War sites, where he took photographs and I made notes for poems and essays.

This was the beginning of a collaboration that has yielded two books and two art exhibitions. When we prepared the exhibition “War Memoranda” for Roanoke’s Taubman Museum in 201), Binh taught me his process and I took on the task of making Civil War-era portraits in leaves to accompany Binh’s portraits of Vietnam-era soldiers he had made in mats of grass-like leaves.

Why, in your estimation, is chlorophyll print making especially apt for memorializing the Civil War?

My very first glimpse of Binh’s leaf prints made me think instantly of Walt Whitman, and the central metaphor of “Leaves of Grass” is the guiding trope of my work: “Tenderly will I use you, curling grass, / It may be you transpire from the breasts of young men, / It may be if I had known them I would have loved them.”

For Whitman, and now for me, the grass and leaves are “hieroglyphics” and “uttering tongues” speaking elegies in spring’s renewals. Also, for Whitman and for me, the grass is a figure for the American ideal of democracy, “Growing among black folks as among white, / Kanuck, Tuckahoe, Congressman, Cuff, I give them the same, I receive them the same.”

When did you first use the Library’s collections, and what is a favorite photo or two you’ve discovered?

In 2012, the Ric Burns Civil War documentary on PBS drew heavily from Drew Gilpin Faust’s 2008 book, “This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War,” and made liberal use of portraits held in the Library’s Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Portraits. That’s when I became aware of the magnificent Liljenquist collection of cased daguerreotypes, tintypes and ambrotypes.

That these portraits were made available on the Library’s website in high-resolution digital images made my work possible. I could download a portrait, print it onto a plastic transparency, place the transparency onto a leaf and put it out for the sun to do its work. Under clear areas of the transparency the leaf would bleach, but under dark areas the shielded parts of the leaf would retain their natural coloration, making the image in the flesh of the leaf.

I was drawn particularly to the portraits of very young soldiers whose expressions are so open, who look so vulnerable. In their new uniforms they appear mildly astonished by their unfolding fate. I’m thinking, for instance, of this unidentified young soldier in a Union uniform and forage cap or Sergeant William T. Biedler of Company C, Mosby’s Virginia Cavalry Regiment, or this unidentified young African American soldier in a Union uniform. I am drawn also to the heartbreaking images of family members in mourning, such as this unidentified girl in mourning dress holding a framed photograph of her father.

Robert Schultz. Photo:

Which works of yours has the Library acquired?

Tom Liljenquist has acquired five of my portraits for the Library. They are based on an African American soldier in a Union uniform holding a rifle-musket and a revolver; the young soldier in a Union uniform and forage cap mentioned above; an officer in Confederate uniform with his wife and baby; a boy holding a photograph of a soldier in Confederate uniform atop a Bible; and Mathew Brady’s 1862 portrait of Walt Whitman.

It is ideal that these pieces will be held with their source material — the small, cased portraits — and near the Library’s great Whitman collection. My work on the leaf prints began with visits to the Library and the Liljenquist Collection, and the Library is the best possible repository for the chlorophyll prints. I know the work will receive excellent care, and I’m honored to have my work made available to its researchers and visitors.

What are you working on now?

A chlorophyll print is a one-of-a-kind piece; a leaf cannot be editioned. So, I have been using my scanner to make digital images of leaf prints that have not yet been cast in resin for framing.

In one new series, “Being Seen,” I scan a leaf portrait, then enlarge the image on my computer and crop it tightly, showing just the face from eyes to mouth. In this work, I’m sharing the intense gaze I have encountered on my computer monitor while preparing images — repairing scratches, adjusting contrast and so on — for use in my processes. The gaze peering intently from my monitor seemed to ask hard questions about the human cost of war.

In another series, “How the Dead Speak,” I make compositions on the scanner using leaf print portraits in combination with fresh plant specimens of various kinds. I make these scans in a darkened room with the scanner’s lid removed. The resulting image shows the composition against a deep, black background. In this work, inspired by Whitman’s great poem, “This Compost,” the dead speak in leaves — in nature’s cycles.

I’ve continued to explore new uses for leaf print portraits. Now I’m making poet boxes, inspired by Joseph Cornell’s three-dimensional compositions made in found wooden boxes. I’ve found a variety of old boxes in antique shops and am currently working on boxes for Walt Whitman, Ezra Pound and Robinson Jeffers. For instance, traveling in California I visited Jeffers’ Tor House, where I was able to gather a few stones, eucalyptus pips and other materials that I will arrange in my box with short poem excerpts and chlorophyll prints of the poet.

I am spending less time in my studio, however, and more time at my desk, working on a novel in which the 1939 World’s Fair figures prominently. Its title will be “How the Future Was.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

November 22, 2021

It’s As If It Was Written in…Clay. For 4,200 Years.

One of the Library’s cuneiform tablets, more than 4,200 years old. African and Middle Eastern Division.

This is a guest post by Leah Knobel, a public affairs specialist in the Office of Communications.

Perhaps the oldest pieces in the Library’s collection of 171 million items are a group of clay tablets from ancient Mesopotamia that date to the dawn of civilization.

The tablets contain an ancient writing system known as cuneiform developed by the Sumerians, who thrived during the third millennium B.C. Sumerians influenced culture and development beyond their original home in Mesopotamia (present-day southern Iraq) — the site of the world’s earliest civilization.

The materials used to create cuneiform — clay and reeds — were both readily available in this region at the time. Initially, cuneiform signs were pictograms but later became based on symbols, causing some ambiguity in their interpretation.

The Library acquired this collection of cuneiform materials in 1929 from art dealer Kirkor Minassian. The items were part of Minassian’s collection of Islamic book-bindings, manuscripts, textiles and ceramic and metal objects that demonstrate the development of writing and book art in the Middle East.

The oldest tablets in the collection date from the reign of Gudea of Lagash, from 2144–2124 B.C. That makes them more than 4,200 years old.

The tablets’ contents are diverse. Several contain inscriptions pertaining to the receipt of and payment for goods and services, while others appear to have served as school exercise tablets, used by scribes learning the cuneiform writing system. These latter tablets were originally unfired, as they were meant to be erased and reused; the account records, on the other hand, were fired and stored for future reference.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

November 19, 2021

China’s Colossal Encyclopedia

Detail from a page in the Yongle encyclopedia. Asian Division.

This is a guest post by Qi Qui, head of scholarly services in the Asian Division. It first appeared in the Library of Congress Magazine’s March/April 2021 issue.

At the dawn of the 15th century, four decades before Johannes Gutenberg introduced the metal movable-type printing press in Europe, the third emperor of China’s Ming dynasty, Zhu Di, ordered the kingdom’s leading scholars to compile a comprehensive work containing all forms of knowledge known to Chinese civilization.

The resulting Yongle encyclopedia, named after the emperor’s reign, comprised 22,937 hand-copied sections bound into 11,095 volumes.

Covered in striking yellow silk, these volumes incorporated a diverse range of topics, from history, art and the Confucian classics to astronomy, medicine and divination. Most of the content was drawn from sections of earlier publications. To facilitate quick searching, compilers arranged entries phonetically into groups according to a standardized rhyming scheme.

More than a century later, after a disastrous fire nearly destroyed the encyclopedia, the Jiajing emperor, Zhu Houcong, ordered a copy of the entire set. A team of 109 court scholars labored over five years before finally completing an exact reproduction in 1567.

Over ensuing decades, however, the original edition was completely lost. Even now, how and when it went missing remains a mystery. Fortunately, parts of the duplicate set have survived — but just barely. Today, only 420 volumes, or 4 percent of the complete set, remain. This includes two newly discovered volumes that sold for more than $9 million at an auction in Paris in July 2020.

Of these, the Library of Congress holds 41 unique, inconsecutive volumes in its Asian Division. Acquired during the early 20th century via purchase and donation, they form the largest assemblage of Yongle specimens outside Asia.

Thanks to collaboration among custodial, cataloging, conservation and digitization teams, the Library’s Yongle collection is now fully cataloged and undergoing careful preservation work. Upon completion of a digitization project in progress, all 41 volumes of this 450-year-old encyclopedia will be made available online for readers around the world to study and appreciate up close.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

November 15, 2021

Researcher Stories: Armand Lione and the Search for Native American History in D.C.

Armand Lione.

American Indians walked the land where the nation’s capital city now stands long before Europeans arrived. Local historian Armand Lione researches that history at the Library.

Tell us about your background and what inspired your research project.

I earned a Ph.D. in pharmacology and toxicology at the University of Rochester in the 1970s and have worked since 1986 as a reproductive toxicologist in D.C. In 2008, I started visiting Melbourne, Australia, and I went back every other year through 2020. Indigenous issues are very important in Australia. When I came back to D.C. in spring 2016, I decided to start researching the Native people of Washington.

I live only a block away from Garfield Park and the former Daniel Carroll Estate on Capitol Hill. To my surprise, those locations turn out to be two of the best documented sites related to the Anacostan Indians (the Latin version of their original name, Nacotchtanks) who once lived in what is now Washington, D.C.

What resources have you used at the Library?

I’ve consulted books from the collections, including works by former National Park Service chief archaeologist Stephen Potter and historian Helen Rountree, as well as articles from online databases — full access to JSTOR at the Library was very productive. I’ve also used maps, such as Andrew Ellicott’s 1790 map, which labeled the eastern branch of the Potomac River as the “Anna Kostia,” and images, including drawings by John White from the 1500s that provide visual records of everyday life among the Algonquins.

What are some striking stories from your Library research?

Samuel Proudfit, in his 1889 work about the Native history of D.C., refers repeatedly to block 736. So, I visited the Geography and Map Division and asked if any information was available about the block. To my pleasant surprise, a staffer brought out a map of the Daniel Carroll Estate. On it, I found there was a spring, which helped explain why Carroll chose the site for his estate and why the Natives before him chose to live there.

Two personal journals also stood out to me — those of colonist and explorer Henry Fleet and physician Almon Rockwell — because they reveal some of the character of the men and aspects of everyday life in the 17th and 19th centuries.

Fleet was captured by the Anacostans in the early 1620s and lived among them for five years until he was 27. Reading his journal, which I accessed in the Main Reading Room, allowed me to document how little he actually said about living with the Indians. “I spent my youth with the Natives,” he wrote just once.

Rockwell, whose journal is also available through the Main Reading Room, was present at the deaths of Presidents Lincoln and Garfield, and he oversaw the construction of Garfield Park in honor of the fallen president. Unfortunately, Rockwell never commented on the Native remains his workmen found when creating the park.

Tell us how you share your findings.

I publish a blog and share my research on a website that features an interactive map showing locations around D.C. where artifacts have been found.

In addition, at the encouragement of Ruth Trocolli, the chief archaeologist of Washington, who is also very interested the city’s Native history, I started the D.C. Native History Project. It consists of a growing group of volunteers who work with local Pistacaway/Conoy tribe members to get recognition for the Anacostan heritage of the area. Our Facebook site now has nearly 150 members.

Also, in 2019 and again this summer, I set up a display in Garfield Park for a day to talk with neighbors about the Native history of the park and Native artifacts found on the Carroll Estate. The Washington Post wrote about my display this year.

Any advice for others who might be interested in researching a topic of interest at the Library?

Delving into the incredible holdings of the Library is made much easier and more productive with the help of the Library’s excellent staff. Talking with an expert staff member about your research interest may open up avenues you haven’t considered and lead you deeper into the wonderful materials in the Library!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

November 10, 2021

Friends, Gifts & Giving: Kaffie Milikin

Kaffie Milikin. Photo: Shawn Miller.

A version of this article first appeared in the November/December 2021 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

This week, the Library launched its new Friends of the Library of Congress program, which brings together a community of donors committed to preserving this nation’s cultural memory. This group is integral in advancing our mission to engage, inspire, and inform and help make everything possible from digital resources to public programming to exhibitions.

We thought it would be a good time to talk to Kaffie Milikin, the Library’s director of development, about the her job and the importance of outside gifts in the overall mission of the Library.

Describe your work at the Library.In a word — thrilling. Each day, I work with some of the most passionate people who want to advance the Library’s mission. My job and the job of every member of my team is to identify philanthropic resources to support that mission. We seek to connect equally passionate philanthropists with the work of the Library. It’s that simple. It’s also very competitive; there are so many worthy causes and opportunities.

How did you prepare for your position?I graduated with a degree in international studies and quickly realized that I had confused it with my love of foreign travel. Since academia always appealed to me, I thought being a professor was the right path. I am proudly “all but dissertation.” It was when my father died that I thought about philanthropy. My mother endowed a scholarship at the University of Florida, and it was a therapeutic experience. My dissertation became unimportant, and an opportunity to learn about fundraising opened at the Whitman Walker Clinic in Washington, D.C. From there, I worked at Georgetown University, George Washington University and the Smithsonian Institution, learning from the ground up. So, my nerd background coupled with my professional experience prepared me to take on the challenge of building a strong philanthropic foundation for the Library.

Why is private support for institutions like the Library so important?Although the U.S. Congress has been the Library’s largest benefactor, support from the private sector amplifies the Library’s core mission; it allows the Library to reach a bit further, stretch in new directions without sacrificing what it does best — preserving and providing access to a rich, diverse and enduring source of knowledge to inform, inspire and engage people everywhere in intellectual and creative pursuits. Our recent success in securing a record $15 million from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation rested on the collaboration and experience of Library staff and their deep knowledge of audiences and collections and purpose. And, yet, every gift matters from every person whether it is $15 or $15 million. Those gifts educate new interns, allow for the acquisition of collection items, make possible new exhibitions and expand our important public-facing initiatives like the Gershwin Prize for Popular Song and the National Book Festival.

What memorable experiences have you had at the Library?In my first few days, I was invited to tour the Preservation Directorate. The Library’s head of book conservation, Shelly Smith, showed me Lincoln’s second inaugural address — the handwritten version and the printed copy believed to be the one from which he read. Whew. It brought up some powerful emotions. When we share the treasures of the Library with our donors, whether on a special tour or through one of the exhibitions, we want to evoke those same powerful feelings about the Library, its staff and collections and the importance of its mission.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers