Library of Congress's Blog, page 34

April 13, 2022

That Night in Detroit: Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’ “

Steve Perry talks about the Detroit inspiration for “Don’t Stop Believin'”

Steve Perry grew up in Hanford, California, a little town about 30 miles south of Fresno, the son of Portuguese immigrants. It was a small farm town with not much happening. Even though he was singing as a 3-year-old, his childhood fantasies of life in the music business seemed oceans away.

But the small-town kid with the big-city dreams not only grew up to be a world-class rock star as the lead singer for Journey, but his unforgettable lead vocals on “Don’t Stop Believin’” helped put the song into the National Recording Registry this year, enshrined as one of the nation’s signature recordings.

“I’m stunned for my parents and my grandparents, who are no longer here, and came to this country as immigrants,” said Perry, 73, in a streaming interview recently. He left Journey and the spotlight more than three decades ago, resides comfortably in California, doesn’t look back on his arena-rock days and rarely gives interviews. But he called the song’s induction into the Registry “the greatest honor of my life.”

“It’s one of those ‘only in America’ kind of things,” he says of his family’s sojourn into the heart of the nation’s culture.

Steve Perry. Photo: Myriam Santos.

Since the song’s 1981 debut, it has become a worldwide hit record, a stadium anthem embraced by multiple sports teams and a key part of the final episode of “The Sopranos,” widely regarded as one of television’s finest dramas.

“That song, over the years, has become something that has a life of its own,” he said. “It’s about the people who’ve embraced it and found the lyrics to be something they can relate to and hold onto and sing.”

Stardom didn’t come easily for Perry, no matter how early his talent showed up.

He followed a high school friend to the Bay Area in the ’60s, sending demo tapes to record labels, but for years nothing worked out. He was in his late 20s, living in a tiny apartment and had all but given up on the business when an executive asked him if he might want to sing with a band called Journey.

They had not had much success and were looking for a new musical direction. He crushed the subsequent audition, then showed up with a flair for songwriting and piercing vocals. Rock fans know the rest. During its heyday in the late ’70s through the ’80s, Journey filled stadiums and sold millions of records with hits such as ” Who’s Crying Now,” “Separate Ways,“Faithfully,” “Lovin’, Touchin’, Squeezin,’ ” “Any Way You Want It” and “Open Arms.”

But nothing shined brighter than “ Don’t Stop Believin’ ” a piece written by Perry and fellow group members Neal Schon and Jonathan Cain. As he recalls it, some of the lyrics came from a concert stop in Detroit, while the finished product was worked out in a warehouse in which the band rehearsed in Oakland, California.

Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin.'” Graphic: Ashley Jones.

Perry is sometimes teased for one of the opening lines in the song, about a character being raised in “south Detroit,” as there is no such district (Detroit rests on a curve in the Detroit River, with Windsor, Canada, being directly south of downtown). He good-naturedly points out that back in the day there was a southbound exit sign on I-75 north of the city that read “South” on one line and “Detroit” beneath it, giving rise to the misunderstanding. Besides, he says, no other direction (east, west or north) sounded right vocally.

The band had finished an enthusiastic show in Cobo Arena in downtown Detroit on tour one night and were staying the night on the top floor of a nearby hotel. Perry, sleepless after the high-energy show, found himself looking out the window, gazing down at people on the sidewalk, milling about.

“The streetlights in Detroit at the time were this kind of orange color…it’s like three in the morning and these people were still standing around, and I thought, ‘Wow, look at these streetlight people, they’re just out in the night.’ ”

Later, it worked into the song this way:

Strangers waiting

Up and down the boulevard

Their shadows searching in the night

Streetlight People

Living just to find emotion

Hiding somewhere in the night

It’s a real-life rock-and-roll story that’s now part of American music history, preserved in the National Recording Registry. Steve Perry, the man who belted it out into late 20th century pop culture, is just glad it resonated with so many people for so long.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Alicia Keys, Journey, “Livin’ La Vida Loca” and the 2022 National Recording Registry

Brett Zongker, chief of the Library’s public relations team, contributed to this article.

The 2022 Class of the National Recording Registry includes albums such as Alicia Keys’ “Songs in A Minor” and singles such as Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’” and Ricky Martin’s “Livin’ La Vida Loca,” along with with important inductions of hip-hop and Latin music, including recordings by Linda Ronstadt, A Tribe Called Quest, Wu-Tang Clan and the Buena Vista Social Club.

Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden today named 25 recordings ̶̶ from a list of nominees by the public and by the National Recording Preservation Board ̶̶ as audio treasures worthy of formal preservation, based on their cultural, historical or aesthetic importance in the nation’s recorded sound heritage.

“The National Recording Registry reflects the diverse music and voices that have shaped our nation’s history and culture,” Hayden said. “The national library is proud to help preserve these recordings, and we welcome the public’s input. We received about 1,000 public nominations this year.”

There are now 600 recordings on the registry, a miniscule portion of the Library’s collection of nearly 4 million recorded items.

Steve Perry, former lead singer of Journey. Photo: Myriam Santos.

“This is the greatest honor of my life,” said Steve Perry, former lead singer for Journey, citing his family’s history as Portuguese immigrants to a small town in California. “I’ve gotten platinum albums and gold albums and I’ve gotten inducted into the Hall of Fame. But for my mother, my father, my grandmother and grandfather, I am truly beside myself that this is happening…it’s an ‘only in America’ kind of thing.”

Alicia Keys, who burst onto the national music scene as a teen prodigy with her 2001 debut album, “Songs in A Minor,” credited her youthful sincerity and original appearance for the album’s lasting resonance.

Alicia Keys’ debut album, “Songs in A Minor,” was inducted into the 2022 class of the National Recording Registry. Graphic: Ashley Jones.

“It was so pure,” she said with a smile during in a recent interview. “You felt the truth that was coming from me. I think that the New York-ness in me was definitely a new energy. People hadn’t quite seen a woman in Timberlands and cornrows and really straight 100% off of the streets of New York performing classical music and mixing it with soul music and R&B and these songs that had big choruses and meaning … and people could find themselves in it.”

The latest selections named to the registry span from 1921 to 2010. They range from rock, pop, R&B, hip-hop and country to Latin, Motown, jazz and news broadcasts. The new class includes speeches by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, WNYC’s broadcasts on 9/11 and Mark Maron’s podcast interview with comedian Robin Williams.

Interviews with several of this year’s artists ̶ including Keys, Perry, Maron and songwriter Desmond Child ̶ are featured on the Library’s website and across social media channels. There will be radio interviews on NPR’s “1A” with several artists in the series, “The Sounds of America. Here on the blog, we’ll feature stories with many of the artists starting tomorrow.

Several recordings joining the registry were influential in helping to deepen the genres of Latin, rap, hip-hop and R&B in American culture. A Tribe Called Quest’s 1991 album, “The Low End Theory” was the group’s second studio release and came to be seen as a definitive fusion of jazz and rap.

Wu-Tang Clan’s 1993 album “Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers)” would shape the sound of hardcore rap and reasserted the creative capacity of the East Coast rap scene. The group’s individual artists would go on to produce affiliated projects that deepened the group’s influence for decades.

While Linda Ronstadt is best known for her work in pop music, in 1987 she paid tribute to her Mexican heritage with her album, “Canciones de Mi Padre,” recorded with four distinguished mariachi bands. The album went double platinum, won a Grammy and is the biggest-selling non-English recording in American recording history.

“I always thought they were world-class songs,” Ronstadt said in an interview with the Library. “And I thought they were songs that the music could transcend the language barrier.”

While she was learning the music and lyrics, Ronstadt said she never worked so hard in her life. By the time she opened a show for the album in San Antonio, it all paid off.

“I looked out to the faces of the audience; it was packed,” Ronstadt said. “There were three generations of families there. They all sang along with the songs. They knew them all. It was really fun.”

When guitarist Ry Cooder and producer Nick Gold assembled an all-star ensemble of 20 Cuban musicians in 1996, the island’s Buena Vista Social Club was reborn to record some of the key Cuban musical styles of son, danzón and bolero. The album’s surprising popularity helped fuel a resurgence of Cuban and Latin music, propelled the band to concert dates in Amsterdam and New York City’s Carnegie Hall and led to a popular film by director Wim Wenders.

Ricky Martin’s self-titled 1999 album cover.

Soon after, a young Puerto Rican singer named Ricky Martin shook things up with “Livin’ La Vida Loca,” a worldwide smash hit in 1999. Written by Draco Rosa and Desmond Child, the song went to No. 1 in 20 countries and was certified platinum in the U.S., the UK and Australia. It remained at No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 for five consecutive weeks. It was named the ASCAP Song of the Year, the BMI Latin Awards Song of the Year and won four Grammys.

“I believe that the energy of a movement is what dominates in that song about Latinos, the empowerment of Latinos,” said Rosa in Spanish. “Life is full of great suffering, and ‘La Vida Loca’ is the total opposite. Let’s live it up, right?!”

Here’s this year’s complete list in chronological order:

“Harlem Strut” — James P. Johnson (1921)Franklin D. Roosevelt: Complete Presidential Speeches (1933-1945)“Walking the Floor Over You” — Ernest Tubb (1941) (single)“On a Note of Triumph” (May 8, 1945)“Jesus Gave Me Water” — The Soul Stirrers (1950) (single)“Ellington at Newport” — Duke Ellington (1956) (album)“We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite” — Max Roach (1960) (album)“The Christmas Song” — Nat King Cole (1961) (single)“Tonight’s the Night” — The Shirelles (1961) (album)“Moon River” — Andy Williams (1962) (single)“In C” — Terry Riley (1968) (album)“It’s a Small World” — The Disneyland Boys Choir (1964) (single)“Reach Out, I’ll Be There” — The Four Tops (1966) (single)Hank Aaron’s 715th Career Home Run (April 8, 1974)“Bohemian Rhapsody” — Queen (1975) (single)“Don’t Stop Believin’” — Journey (1981) (single)“Canciones de Mi Padre” — Linda Ronstadt (1987) (album)“Nick of Time” — Bonnie Raitt (1989) (album)“The Low End Theory” — A Tribe Called Quest (1991) (album)“Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers)” — Wu-Tang Clan (1993) (album)“Buena Vista Social Club” (1997) (album)“Livin’ La Vida Loca” — Ricky Martin (1999) (single)“Songs in A Minor” — Alicia Keys (2001) (album)WNYC broadcasts for the day of 9/11 (Sept. 11, 2001)“WTF with Marc Maron” (Guest: Robin Williams) (April 26, 2010)Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

April 11, 2022

Jason Reynolds: April Newsletter

You know what I’ve been thinking about lately? Awards. Maybe that’s because we’re in the midst of awards season in the entertainment industry, the Oscars and Grammys having just recently taken place. And every year, during this time, I’m glued to the television, watching people get nominated for their talent. And every year, I watch about 90 percent of them lose. The handful that win, they usually get on stage and thank their fellow nominees, their families and their teams, but most of them also make it a point to take a moment to shine light on something a bit more serious than a movie, or a song.

You know what I’ve been thinking about lately? Awards. Maybe that’s because we’re in the midst of awards season in the entertainment industry, the Oscars and Grammys having just recently taken place. And every year, during this time, I’m glued to the television, watching people get nominated for their talent. And every year, I watch about 90 percent of them lose. The handful that win, they usually get on stage and thank their fellow nominees, their families and their teams, but most of them also make it a point to take a moment to shine light on something a bit more serious than a movie, or a song.

This is usually the part of the speech that brings me to tears. The reason being, it’s the part of the speech that actually matters to me. Because though I am happy for the winner (usually), I don’t know their families, or their agents and managers, or the directors of their movies, or the producers of their albums. I don’t know any of the people who have helped to get them where they are, on that big stage with the bright lights, dressed in gorgeous garb, glammed up from head to toe. That feels far away. But to bring light to an injustice, to some of the loose threads in our world, some of our jaggedness, I am suddenly transported from my living room into the theater. Or maybe they are transported from the theater into my living room, and we are now crying together. On my couch. Crying for our lives, or loves, or world.

And sometimes, I wonder if some of the artists who didn’t win had something even more poignant to say. What if one of the nominees who stayed seated had the key to some part of my emotional prison and could’ve set a sliver of me free? Or could’ve said the thing to spark a global movement? Or could’ve honored a quieted human who deserves more light than any of our entertainers? How would we ever know? What if? What if?

What’s the point of all this, you ask? Well … I don’t know. I guess, as someone who has received awards, I’m just thinking about how we want to win them for our work, to be praised for our efforts and abilities, but I’m not always sure our work is worth anything if the people we make it for can’t be free. It doesn’t mean we can’t provide a smile or a moment of respite, but a broken world can’t be healed by a Band-Aid, no matter how creative it might be. So maybe we — or at least I — will start thinking of awards as just opportunities to shine light on someone other than myself. And if we all were to think of awards that way, no one, or at least the people who actually matter, could ever lose. We’d be fighting, yearning, hoping for the victory of us all.

Or at least the opportunity to say that victory, as it pertains to free life, should stretch beyond any red carpet or ballroom.

Thinking of Ukraine. And you.

As ever,

Jason

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

April 7, 2022

Jelly Roll Morton at the Library

Jelly Roll Morton. Photo: Unknown. American Folklife Center.

This is a guest post by Stephen Winick, folklore specialist at the American Folklife Center. It first appeared in the Library of Congress Magazine. He has also discussed Jelly Roll Morton’s work at a Library seminar.

In the early history of jazz, no figure looms as large as Ferdinand LaMothe, better known as Jelly Roll Morton.

The New Orleans native, who claimed to have invented jazz itself in 1902, was a bandleader and pianist on numerous recordings in the 1920s but fell into relative obscurity in the 1930s.

Then, in the spring and summer of 1938, Alan Lomax, the assistant in charge of the Library’s Archive of American Folk Song, recorded over nine hours of Morton’s singing, playing and boasting — the first extensive oral history of a musician recorded in audio form.

The sessions were born when BBC radio journalist Alistair Cooke advised Lomax to seek out Morton at the Music Box, a small Washington, D.C., nightclub where he played piano, regaled the audience with tales of his glory days and expressed his strong views on jazz history.

Lomax visited the Music Box and chatted with Morton, who suggested the recording sessions as a way to cement his place in history as the inventor of jazz. This suited Lomax, who had his own agenda for the sessions: in his words, “to see how much folklore Jelly Roll had in him” and capture it for posterity.

Seated at a grand piano on the Coolidge Auditorium stage, Morton filled disc after disc with blues, ragtime, hymns, stomps and his own compositions. He embedded the music in a series of swinging lectures on New Orleans music history and its influence on his style — everything from 19th-century opera to formal French dance music to the chants he sang as a “spyboy,” or scout, for a Mardi Gras Indian krewe.

Morton, posing in formal wear for a publicity shot. Photo: Unknown. American Folklife Center.

The recordings not only documented Morton’s playing and his stories, they were the first — and last — significant documentation of Morton as a singer.

Shortly after the Lomax interviews, Morton was stabbed by a Music Box patron and never fully recovered. He left for New York and then Los Angeles, intending to restart his career, but died in 1941. Lomax used the interviews to write a 1950 biography, “Mister Jelly Roll,” which still is considered a classic of jazz literature.

The Library’s Morton recordings were released as a piano-shaped box set by Rounder Records in 2005 and won Grammy awards for best historical album and best liner notes. Today, the recordings are a priceless document of American musical history, rightly enshrined by the Library in the National Recording Registry.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

April 5, 2022

New from Library’s Crime Classics: “The Conjure-Man Dies”

“The Conjure-Man Dies,” by Rudolph Fisher. Cover art is adapted from a photograph by Camilo José Vergara. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Zach Klitzman, the editorial assistant in the Library’s Publishing Office .

The latest entry in the Library’s acclaimed Crime Classics series is a new edition of “The Conjure-Man Dies,” a product of the Harlem Renaissance and the most important work of long-overlooked writer Rudolph Fisher. First published in 1932, the book was the first full-length mystery novel to feature an all-Black cast of characters, including detectives, suspects and victims.

In the 1920s and the 1930s, African Americans in New York and other cities produced a major outpouring of arts, music and literature. This explosion of culture—nicknamed the Harlem Renaissance after the New York neighborhood where many of these artists lived—was the result of several factors, most notably the Great Migration, when millions of African Americans sought job opportunities in northern cities like New York, Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. Many luminaries from this period, such as poet Langston Hughes, musician Duke Ellington, actor Paul Robeson, writer Zora Neale Hurston and singer Bessie Smith remain among the most celebrated figures in American arts and letters.

Fisher, though, faded from view as the years passed.

A writer, orator, musician, physician and radiologist, he was a renaissance man. Hughes, a close friend, noted in his autobiography that Fisher “frightened me a little, because he could think of the most incisively clever things to say—and I could never think of anything to answer.” Fisher passed away from cancer at the age of 37 in 1934, cutting short a promising career.

“Conjure-Man” is a fitting title for the Crime Classics series. Launched in 2020, the series features some of the finest American crime writing from the 1860s to the 1960s. Drawn from the Library’s collections, each volume includes the original text, an introduction, author bio, notes, recommendations for further reading and suggested discussion questions from mystery expert Leslie S. Klinger. This special edition also features exclusive reminiscences from Fisher’s granddaughter, Laurel Fisher.

The book’s plot: N’Gana Frimbo, the titular “conjure-man” from Africa, is discovered bludgeoned in his consultation room. Perry Dart, one of Harlem’s few Black police detectives, arrives to investigate. Together with Dr. Archer, a physician from across the street, Dart is determined to solve the mystery, while Bubber Brown and Jinx Jenkins, local hustlers keen to clear themselves of suspicion of murder, undertake their own investigations. The book is full of local slang, what Fisher called “Harlemese,” adding a distinct authenticity to this groundbreaking novel.

Fisher received bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Brown University (he graduated Phi Beta Kappa) before graduating from Howard University’s medical school with more honors in 1924. He soon moved to Long Island with his family, where he began a medical practice specializing in X-rays. The same year he graduated medical school, he published his first piece of fiction, a short story entitled “The City of Refuge” in the Atlantic Monthly. He published 15 more short stories, which were highly regarded.

A Federal Theater Project photograph from the 1936 production of “The Conjure-Man Dies.” Music Division.

His first novel, “The Walls of Jericho,” appeared in 1928. The novel centers on a Black lawyer who buys a house in a white neighborhood bordering Harlem, and the ensuing antagonism of his new neighbors. The tone is more satirical than menacing, with Bubber and Jinx also making appearances, prefacing their comic turns in “Conjure-Man.”

When Fisher died in 1934, he was in the middle of adapting “Conjure-Man” as a stage play. Two years later, the play debuted at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem, produced by the Negro Unit of the Federal Theatre Project. The FTP was a New Deal program that provided grants to actors, directors, and other theater professionals from 1935 to 1939. Two dozen photos of the play can be seen as part of the Federal Theater Project’s online collections.

Detail from the playbill of “The Conjure-Man Dies.” Music Division.

The Library is home to a wealth of resources related to the Harlem Renaissance. Jazz enthusiasts will dig William P. Gottlieb’s photographs of musicians like Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. Ten of Zora Neale Hurston’s original plays are held in the Manuscript Division. And the Federal Writer’s Project contains many first-hand narratives of life in Harlem during this time period. For more Harlem Renaissance material, check out this research guide.

Crime Classics are published by Poisoned Pen Press, an imprint of Sourcebooks, in association with the Library of Congress. The Conjure-Man Dies, published on April 5, is available in softcover ($14.99) from booksellers worldwide, including the Library of Congress shop.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 31, 2022

Shackleton’s Antarctic “Turtle Soup” Book

The classic night photo of the Endurance, stuck in polar ice. Photo: Frank Hurley. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Abby Yochelson, a reference specialist in the Main Reading Room.

When the well-preserved wreck of the Endurance recently was discovered deep in the Antarctic’s icy waters more than a century after it sank, international headlines followed.

The Endurance was last seen in 1915, when it became trapped and slowly crushed by pack ice during an expedition headed by renowned polar explorer Ernest Shackleton. The three-mast, 144-foot ship sank beneath the ice and waves of the Weddell Sea, falling some 10,000 feet to its watery grave. Shackleton and his crew of 27 survived, but only by a series of death-defying ocean voyages in a lifeboat. It’s widely celebrated as one of the great survival stories of modern times; the Library’s online catalog lists 75 titles about the expedition.

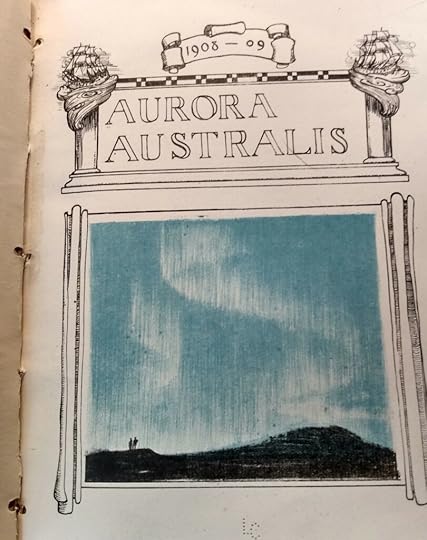

But an earlier Shackleton voyage to Antarctica also produced a remarkable book, if one not nearly so dramatic. “Aurora Australis,” put together during Shackleton’s 1907-1909 polar voyage, is the first book “written, printed, illustrated and bound in the Antarctic,” as Shackleton put it. Fitting for its harsh native environment, about 25 copies were bound with packing crate boards repurposed from the ship’s pantry. The Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division has one of these, marked with “turtle soup” and “honey” for their original contents. About 60 or 70 more were printed, but were never bound. Scholars think about 75 total copies, bound or unbound, still exist.

The frontispiece of “Aurora Australis.” Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

“Aurora,” edited by Shackleton and illustrated by George Marston, is an illustrated anthology with three poems, seven articles of fiction and nonfiction, all written by crew members and scientists while they were huddled at the expedition’s cramped winter quarters. The lovely title is taken from the sky lights seen in the Southern Hemisphere, similar to the more familiar aurora borealis in the Northern Hemisphere.

It doesn’t have a daring plot of survival but it does have those wooden covers!

The inside cover of the Library’s copy of “Aurora,” made from a packing crate of turtle soup. The book has been turned sideways for the photo. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

They’re marked for mouth-watering items such as butter, sugar, stew, petit pois, beans, chicken and oatmeal. The Library’s copy, with “turtle soup” and “honey,” make for an unlikely combination gastronomically, but these boards cover our book in fine fashion.

This Shackleton expedition was the first to ascend 12,448-foot Mount Erebus, the volcanic peak that is the second highest point on the continent, so much of the book covers that work. There’s an illustration, “Under the Shadow of Mt. Erebus,” by Marston; a nonfiction account of the climb, “The Ascent of Mt. Erebus,” by T.W. Edgeworth David, director of the scientific staff; and a ballad in rhymed couplets, “Erebus,” by Nemo, presumably a pseudonym for one of the crew.

One would think that “Life Under Difficulties” describes the harsh conditions experienced by the crew. Instead, James Murray, a biologist, provides a detailed examination of rotifers, “beautiful little cone-shaped animals of crystal transparency, with a ruby-red eye in the middle of the large head.” (At least this is what these sea creatures might look like if you could examine them under a microscope.)

Undated photo of Ernest Shackleton . Photo: Bain News Service. Prints and Photographs Division.

While some of the articles describe daily life, others are more fanciful. “An Interview with an Emperor” features an Emperor Penguin speaking in something like a Scots accent – and accusing the crew’s geologist (the article’s author) of stealing rocks. “An Ancient Manuscript” is written in Biblical prose for comic effect:

“Go thou therefore, dwell in this land, travel over the face of the same, tear out its secrets, and should it also be that thy hand shall uproot the great pole which the wise men do call the South Pole; then do I say unto thee that it shall not be forgotten of thee in the years which are to come.”

The discovery of the Endurance will undoubtedly trigger new fascination in that expedition’s story and admiration for the polar explorers of the era. Reading “Aurora Australis,” though, provides a glimpse into the creative and often humorous side of these adventurous men and their determination to gain an understanding about unknown parts of our world.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 28, 2022

“Not an Ostrich” Exhibit Now at the Library

An unnamed photographer for the H.C. White Company nonchalantly checks his camera, perched on a steel beam 250 feet in the air. Detail from a stereograph. Photo: H.C. Hine Co. Prints and Photographs Division.

The title of the Library’s just-opened exhibition, “Not an Ostrich,” is certain to make some people scratch their heads, wondering, “What on earth could this be about?” For many of them, the Library hopes, it will inspire a trip to the Jefferson Building to find out. Since we’re now open again, we invite you to see for yourself — but you can check out the exhibition online, too.

Either way, you’ll discover the power of photography. More than 400 pictures from the Library’s holdings take viewers on a journey through America’s history — from the beautiful and the heartening to the disturbing and the humorous.

Along the way, they’ll learn about the Library’s vast photographic collections, the art of photography and some of the women and men who have gone to extraordinary lengths to document the American scene. The pictures extend from the earliest photographic process (Robert Cornelius’ 1839 daguerreotype self-portrait) to the latest in digital photography (a Camilo José Vergara’s 2017 Harlem streetscape).

“Please take a moment to stop by the show. You can dip in and out, and you’re sure to find at least one image that will stop you in your tracks for a closer look or bring a smile to your day,” said Helena Zinkham, chief of the Prints and Photographs Division.

Renowned photography curator Anne Wilkes Tucker organized the exhibition, whose full title is “Not an Ostrich: And Other Images from America’s Library.” It debuted in 2018 in Los Angeles at the Annenberg Space for Photography, which enlisted Tucker as curator. At the Library, it will open in the Jefferson Building’s southwest gallery.

To put the show together, Tucker visited the Library monthly for a year and a half, working closely with photography curator Beverly Brannan and other specialists to identify images to feature. The task was enormous, considering that the division holds more than 14 million photographs, and Tucker was asked to include undigitized and never-before-exhibited items among her selections.

“I just sat there, and the staff brought me pictures,” Tucker told the New York Times in 2018. “I never knew what I was going to get. I looked at slides. I looked at contact sheets. I looked at prints. I looked at stereos. … I loved it.”

Tucker estimates that she looked at nearly a million images. “I would pick pictures that struck me visually,” she recounted in an interview with the magazine Hyperallergic. First, she whittled her choices down to about 3,000, then to around 400 that she feels are “a true representation of the Library’s collection.”

Her selections include icons such as “Migrant Mother” by Dorothea Lange, “American Gothic” by Gordon Parks, a photo of the Wright Brothers’ first flight and a recently acquired portrait of a young Harriet Tubman.

But they also include hundreds of images of everyday people going about their lives over the decades from West to East, North to South. Some are joyous (a girls’ soccer team celebrating a win). Some are troubling (a Black teenager being harassed at a North Carolina school). And others are fascinating — some in a scary way (a photographer perched atop an under-construction highrise).

The exhibit’s signature photo, “Not an Ostrich,” depicts actress Isla Bevan holding a goose — definitely not an ostrich — at a 1930 poultry show in Madison Square Garden. For those interested in actual ostriches, there’s even an 1891 photograph of a peddler of feather dusters, often made from ostrich plumes.

British actress Isla Bevan holding an exotic, Sebastopol goose as the 41st annual Poultry Show at Madison Square Garden in 1930. Photo: Unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

Tucker made sure to include the work of photographers of many different interests and backgrounds — more than 140 — in the exhibit. For example, the show includes a photo of the Apache leader Geronimo by Emme and Mayme Gerhard, trailblazing early 20th-century camerawomen; a hula-hooping grandmother by Sharon Farmer, the first African American woman to serve as White House photographer; and a self-portrait by Will Wilson of the Navajo Nation.

In support of the Annenberg show, the Library released more than 400 photos online from the exhibit, many newly digitized and rarely seen publicly before.

The Library’s presentation of “Not an Ostrich” is mostly, but not exactly, the same as the Annenberg exhibit. That’s because the Library’s gallery does not perfectly mirror the more modern Annenberg space, and some captions were edited for the Library’s audience, said Cheryl Regan of the Exhibits Office.

At the Library, the show has 11 sections mounted across 10 walls. About 70 framed reproductions are included — the exhibit consists exclusively of reproductions — accompanied by digital slide shows featuring hundreds more photographs and a 30-minute documentary, “America’s Library.”

Eight exhibit sections explore the categories of photographers; panoramas; portraits; icons; the built environment; arts, sports and leisure; social, political and religious life; and science and business. Another three cover the work of Vergara, Carol M. Highsmith and the Detroit Publishing Company.

The latter two share a wall, offering views of America separated by a half century or so. Highsmith has been documenting the nation’s culture, people and landscapes for more than four decades. Before her, the Detroit Publishing Company, one of the world’s major image producers from 1895 to 1924, chronicled natural environments and cities across the U.S.

“Taken together, the scope and sheer tenacity applied by both Carol Highsmith and the Detroit Publishing Company in creating a visual portrait the United States is awe inspiring,” Regan said.

Besides the juxtaposition of Highsmith and Detroit Publishing, Regan said she finds photos by Stanley Kubrick especially intriguing — there are two in the show. One is a 1947 photo of the bodybuilder Gene Jantzen with his wife and baby son; the other is a quirky image of three men testing a mattress at a 1950 furniture convention.

Lookit those baby biceps! Iconic film director Stanley Kubrick took this kinda strange picture of bodybuilder Gene Jantzen with wife Pat and eleven-month-old son Kent. Photo: Stanley Kubrick. Prints and Photographs Division.

Known for his films — “Lolita,” “Dr. Strangelove,” “2001: A Space Odyssey,” “A Clockwork Orange” — Kubrick was a staff photographer at Look magazine before he pursued filmmaking.

“It’s interesting to look at young Stanley Kubrick and try to figure out, is his aesthetic getting established early on, so that it comes out in his later film work in interesting ways?” Regan said.

Personal tastes aside, Regan believes visitors will find the exhibit exciting. “I hope that they find surprises, that it piques their curiosity,” she said. “I hope they go online to see millions more images in the Library’s collections.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

March 25, 2022

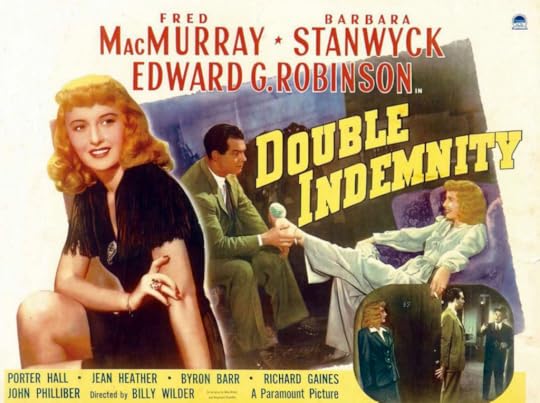

The (Very Polite) Letters Behind “Double Indemnity”

“Double Indemnity” was so daring by 1944 standards that some lobby cards tried to make the crime noir tale look more like a romantic comedy. Paramount Pictures.

“Double Indemnity” is one of Hollywood’s classic films, the standard-bearer for noir cinema and a career highlight for stars Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray. With the Oscars being handed out Sunday, it’s good to keep in mind that the Billy Wilder-directed “Double,” with a legendary script by Wilder and crime-writer icon Raymond Chandler, was nominated for seven Academy Awards in 1945.

It’s also good to keep in mind that it won exactly zero.

In Hollywood lore, it’s one of the all-time snubs, joining cultural touchstones such as “Singin’ in the Rain” and “Vertigo” as films that won a place in history but not at the Oscars. It was, however, inducted into the Library’s National Film Registry in 1992, recognized as a film of national cultural importance.

The Library has a fascinating exchange of letters between the “Double” stars and novelist James M. Cain, whose book was the basis for the film. (Cain also wrote “” also made into a noir classic that also won no Oscars.)

The letters, contained in Cain’s papers at the Library, give us a glimpse into Hollywood history, how scandalous the movie was at the time and at the manners of a bygone era. Today, stars tag their peers in tweets; in the 1940s, they sat down at a typewriter or picked up a pen and wrote letters. There was a formality, a way things were done, that has been obliterated by changing times and technology. It’s almost impossible to imagine the following exchange taking place today.

“Dear Mr. MacMurray,” Cain typed on Feb. 4, 1944, after they both attended a Los Angeles premiere of “Double” from which MacMurray had ducked out early, meaning Cain had missed him at the ensuing reception. “Your portrayal of that character is simply terrific, and the way in which you found tragedy in his shallow, commonplace, smart-cracking soul will remain with me a long a time … (if) I ever weaken and begin to pretty my characters up, I shall remember your Walter and be fortified.”

Cain’s congratulatory note to MacMurray, Feb. 4, 1944. Manuscript Division.

This was more than Tinseltown gushing.

“Double” was outrageous and dangerous, the kind of fare that gave stars pause about lending their names to it, particularly in the era when Hollywood was governed by the censors at the Motion Picture Production Code.

First published as a magazine serial in 1936, “Double” is the tale of lusty Los Angeles insurance agent Walter Neff (MacMurray), who makes a house call on a rich client, the scent of honeysuckle in the air, only to find the husband absent and his bewitching spouse, Phyllis Dietrichson (Stanwyck), clad in nothing more than a towel and a smirk.

Swilling bourbon and trading double-entendres, the pair soon kill the husband, framing it as an accident so they can collect a fat insurance payout. It ends in double-crosses, gunfire and regret.

“I killed (the husband) for money and a woman,” MacMurray’s character says in the movie’s most famous line. “I didn’t get the money and I didn’t get the woman.”

“I killed a man for money and a woman….” MacMurray and Stanwyck in a key moment from “Double Indemnity.” Paramount Pictures.

Few mainstream stars wanted to play such a role, and MacMurray, a straight arrow if ever there was one, seemed spectacularly unfit for it. He grew up in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, for heaven’s sake, and spent the 1930s in the studio system playing nice guys in lighthearted pictures. By the early’40s, he was one of the highest–paid actors in the trade, making $430,000 (about $7 million today), according to his biography on the Internet Movie Database.

We can deduce that MacMurray was a polite man who observed social courtesies because he answered Cain’s letter immediately, with a space of just five days between the two letters. But he responds to Cain’s typewritten missive with a handwritten note — a personal touch. He was a big star, after all, and perhaps didn’t want Cain to think he’d had a secretary knock this out.

“Dear Mr. Cain — I want to thank you for your very nice letter,” he began, in keeping with the social graces of beginning a thank you note with — well — a thank you.

Then he politely addressed the elephant in the room.

“As you’ve probably been told, it took a lot of persuading by a number of people to get me to tackle the part. I was crazy about the story — but having never done anything like it, I was afraid to take a crack at it. Even after seeing the finished picture, I was sure I’d given an Academy performance — in underacting! But if you, the author, liked it — that’s good enuff for me!”

Excerpt of MacMurray’s note to Cain, with the intentional misspelling of “enuff” in the final line. Letter dated Feb. 9, 1944. Manuscript Division.

Here, we pause to note the aw-gee-shucks intentional misspelling of “enough,” and you can see that while Fred MacMurray was indeed a big-bucks Hollywood movie star, he had not forgotten his humble roots in dear old Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, and wanted Cain to know that he was still a regular fella.

I happened across this letter a couple of years ago in Cain’s papers. It was unmarked, just another letter among his correspondence, in a folder headed “Miscellaneous — M.” It was so unexpected, so absolutely charming, such a valentine from one of the most famous movies in Hollywood history, that I was transfixed.

Then, wondering if lightning might have struck twice, I went to the folder of Cain’s letters marked “Miscellaneous — S” to see if there might be something from Stanwyck.

Bingo! On personalized stationery, even, a thing which serious people had back then.

“Dear Jim,” she began in her flowing penmanship, on Feb. 23, 1950, not only dispensing with the formality of a typewriter but also with the “Mr. Cain” business. Six years had passed since the movie had been a critical and commercial hit. She’d been nominated for an Oscar as best actress for her portrayal.

“Dear Jim, Thanks so much for your letter regarding our ‘Indemnity’ broadcast. Believe me, it’s my favorite and always a joy for me to do…” the first lines of Stanwyck’s letter to Cain, Feb. 23, 1950. Manuscript Division.

“Double” had proved such an enduring hit, in fact, that she had reprised her role in a nationally broadcast radio play of the tale in 1945 with MacMurray, and then again in 1950 opposite actor Robert Taylor. Cain, who had moved back to his native D.C. region, sent her a complimentary note after hearing this later version.

She responded quickly, writing him that playing the wicked Phyllis was “my favorite” and “always a joy.” She then noted that he’d promised to write a new book with a tailor-made role for her to perform on film; was that what he was working on now? “If not Jim — remember your promise before I get too bloody old. Good luck my friend and I hope to see you when you return here. Fondly, Barbara.”

Cain went on to write more than a dozen novels, but nothing ever matched his previous intensity and there was never another part for Stanwyck. He later said he should have never left Hollywood. He spent his last years in Hyattsville, Maryland, writing grandfatherly like columns for The Washington Post.

MacMurray, with the exception of “The Apartment,” returned mostly to playing Mr. Nice Guy roles, anchoring a series of Disney films in the ’60s (“The Absent-Minded Professor,” “The Happiest Millionaire,”) and as the cardigan-wearing, pipe-smoking dad on television’s “My Three Sons” for more than a decade.

Stanwyck worked in films until the late 1950s, then switched to television, becoming a small-screen star on “The Big Valley” in the ‘60s and in the ’80s nighttime soap, “Dynasty.”

But there’s no doubt the most enduring work of all three was in that hot, sexy, dangerous film of 1944, when they all stepped out of themselves to play mean little people doing mean little things — and then wrote each other such nice, polite letters about how fun it all had been.

“I hope I may sometime have another opportunity to do one of your very interesting characters — Thanks again — Fred MacMurray” The close of MacMurray’s thank-you note to Cain. Manuscript Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 23, 2022

Madeleine Albright: A Life of Courage and Commitment

Madeleine Albright, the first female Secretary of State, died today in Washington.

She was 84. The cause was cancer, her family said in a statement.

Albright, who donated her papers to the Library in 2014, was a key figure in the administration of Bill Clinton, serving first as ambassador to the United Nations and then as Secretary of State during his second term. Her no-nonsense foreign policy was informed by her childhood experiences as her family fled from her native Czechoslovakia, first running from the Nazi regime of Germany and then the Communists from Russia. Her family came to the U.S. in 1948.

After her trailblazing career as a public servant, she wrote several bestselling books, including “Madam Secretary: A Memoir,” “Fascism: A Warning,” and “Hell and Other Destinations: A 21st-Century Memoir.” She was at the National Book Festival in 2020. In an interview with David Rubenstein, she mused that she was irritated, if not angered, by women who did not support one another: “There is a special place in hell for women who don’t support each other,” she said.

She was never out of touch with world events, writing an op-ed in the New York Times in late February, warning about Russian leader Vladimir Putin’s decision to mass troops on the border of Ukraine. The piece is vintage Albright, mixing her role in world affairs with her unapologetically blunt viewpoint.

“Should he invade,” she wrote, “it will be a historic error.”

She is remembered fondly at the Library, where she toured her collection in the Manuscript Division in 2020, chatting with the staff and posing for photographs.

“Madeleine Albright shined on the world stage as a symbol of peace & diplomacy,” Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress, said in a statement. “As the first female Secretary of State she was a trailblazer and role model. Her memory will live on at the Library of Congress where we are honored to be custodians of her papers.”

March 22, 2022

My Job: Elizabeth Novara, Historian of Women and Gender

Elizabeth Novaro. Photo: Pete Duvall.

Elizabeth Novara is the historian of women and gender in the Manuscript Division.

Tell us about your background.

I grew up in a rural area in western Maryland and have lived in various places around the state, so I’m a local to this region. I attended Saint Mary’s College of Maryland as an undergraduate, majoring in history and French. Then, I earned master’s degrees in history and in archives, records and information management through the history and library and information science programs at the University of Maryland (UMD), College Park.

After getting married and becoming a mom, I decided to return to graduate school at UMD part time while continuing to work full time. I earned a graduate certificate in women’s studies, and I am now a Ph.D. candidate in American history focusing on women’s suffrage history.

Before arriving at the Library, I was a tenured faculty curator of historical manuscripts for UMD Special Collections for over 10 years, and I held other positions at the UMD Libraries. As a manuscripts curator, I was responsible for special collections materials relating to Maryland history and culture, historic preservation and women’s studies.

What brought you to the Library, and what do you do?

The amazing women’s history collections in the Manuscript Division and throughout the Library — and the fact that the Library is just amazing!

Early in my professional career, I became involved in the Women’s Collection Section of the Society of American Archivists. When I realized there were jobs in the archives field focused on my specific research and writing interests, a position concentrated on women’s history became a professional goal. I was also very fortunate to have a job at UMD that allowed me to work with women’s studies collections and to hone my scholarly pursuits on women’s history.

My position at the Library as a manuscript historian for women’s and gender history really is the perfect intersection of my expertise, training and interests. My major responsibilities include acquisitions, outreach and reference related to the Manuscript Division’s women’s history collections.

What are some of your standout projects?

When I first arrived at the Library, I was immediately immersed in the task of being a co-curator of the exhibition “Shall Not Be Denied: Women Fight for the Vote” with Janice Ruth and Carroll Johnson-Welsh. I was also involved in many outreach initiatives (exhibit tours, lectures, conferences, published works) related to the exhibition from 2019 through 2021.

I am also very proud to have been the Library’s main point of contact for the recent acquisition of a major addition to the National Woman’s Party (NWP) records. The addition, dating from the 1860s to the 2020s, contains over 300,000 items and is currently being processed by Manuscript Division archivists and technicians.

An important scholarly resource, these materials document the efforts by the NWP to promote congressional passage of the federal women’s suffrage amendment and the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), as well as to ameliorate the legal, social and economic status of women in the U.S. and around the world.

Most recently, with Manuscript Division reference librarian Edie Sandler, I published a revised and updated version of American Women: Resources from the Manuscript Collections, part of the Library’s larger American Women Guide Series. The guide highlights many of the women’s history collections in the Manuscript Division. It was a pleasure to collaborate with Edie and division reference staff on its publication.

What do you enjoy doing outside work?

Outside of work, I enjoy spending time with family; taking long walks or runs in Rock Creek Park; gardening; visiting museums and other cultural heritage institutions (especially ones that are local and off the beaten path); and, oh yeah, researching for my dissertation. When I have time, I also love baking pies with locally grown fruit.

What is something your co-workers may not know about you?

As an undergraduate, I spent my junior year studying and living abroad in Paris and traveling as much as possible. This experience had a lasting impact on my life, opening my perspectives to other cultures and creating lifelong friendships.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers