Library of Congress's Blog, page 33

May 9, 2022

Historical Documentaries are the Key to Understanding Our Common History as Americans

Elizabeth Coffman, director of “Flannery,” accepts the 2019 Library of Congress Lavine/Ken Burns Prize for Film from from Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden and filmmaker Ken Burns. Photo: Shawn Miller.

This is a guest post by Courtney Chapin, Executive Director of The Better Angels Society.

Looking together at our common history is a way for Americans to see one another, to celebrate what makes us similar and what makes us different. The turbulence of the present moment is a wake up call for us to reflect deeply on how we arrived here, and the medium of film makes that history accessible to as many as possible – providing a hearth around which we can gather to consider the ideas and events that bind us together across time.

There’s never been a greater need for historical documentaries. They are essential to examining our past, understanding ourselves, and building a national discourse on what defines us as Americans. They have the power to educate, inform, and provoke thoughtful discussion with friends and family, making us wiser and our democracy stronger. That’s why The Better Angels Society, the Library of Congress and the Crimson Lion/Lavine Family Foundation established the Library of Congress Lavine/Ken Burns Prize for Film in 2019.

The Prize annually recognizes a history documentary in the late stages of completion that uses original research and compelling narrative to tell stories that bring American history to life using archival materials. Our goal when establishing the prize was to lift up the abundance of talent in documentary filmmaking, which might not otherwise have a path to sharing their work more widely. The winner receives a $200,000 finishing grant to help with the final production and distribution of the film. In addition, one runner-up receives a grant of $50,000 and three to four finalists each receive $25,000. These funds are used for finishing, marketing, distribution and outreach.

Last year’s winner, “Gradually, then Suddenly: The Bankruptcy of Detroit” (directed by Sam Katz and James McGovern), paints a vivid picture of city once heralded as the spirit of American manufacturing, music, and democracy. But Detroit kicked its fiscal can down the road for decades, eventually plummeting into insolvency and culminating in the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history. The film tells the inside story of how a state-appointed Emergency Manager and the people of Detroit confronted financial ruin and navigated a treacherous path towards a new beginning.

Other films have focused on lesser known stories. A 2021 finalist, “The Five Demands” (directed by Greta Schiller), paints the picture of the 1969 student strike at the City College of New York. Although waves of student activism took place in the late ’60s, most stories widely known today revolve around white, middle- to upper-class students. Yet, Black and Puerto Rican students led a little-known national Black student movement that transformed the culture, mission and curriculum of higher education. And 2020 finalist “Punch 9 for Harold Washington” (directed by Joe Winston) told the story of Chicago’s first African-American mayor, who paved the way for many future political leaders–including former President Barack Obama.

Since we established the Library of Congress Lavine/Ken Burns Prize for Film, we’ve experienced countless events that have united and divided us – a pandemic, a presidential election, global conflict, cultural shifts and environmental flux. In times like these, we are committed to bringing philanthropy to American history documentaries so that Americans have quality history stories to turn to in order to gain a clearer perspective on the present. Submissions for this year’s prize are open, and we encourage documentary filmmakers to share their work and help us understand the past and provide greater depth to the present. To learn more about submission guidelines and deadlines, visit The Better Angels website.

May 5, 2022

The Roots of Cinco de Mayo: The Battle of Puebla

A poster for a Cinco de Mayo celebration in San Francisco in 1984. Artist: Réne Castro. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Maria Peña, a public relations strategist in the Library’s Office of Communications.

A batch of 36 Mexican letters recently acquired by the Library not only offers a vivid description of the last months of the Second French Intervention in Mexico, including the Battle of Puebla (Cinco de Mayo) in 1862, but also the complex alliances of global powers jousting for influence in the Americas against the backdrop of the U.S. Civil War.

The letters, obtained from a rare books dealer, offer a reminder that Cinco de Mayo is not a celebration of Mexican independence, as is often assumed in the U.S., but rather an unexpected victory over French invaders that also helped sound a death knell for the Confederates in the Civil War.

“The United States was divided in civil war at the same time, with concurrent definitive battles in Arizona and New Mexico — all part of the area ceded to the United States by Mexico just 14 years earlier,” said Suzanne Schadl, head of the Latin American, Caribbean and European Division. “These letters offer researchers an opportunity to examine another piece of a complex puzzle during the mid-1800s in North America.”

The new collection of letters by Mexican historical figures, still to be digitized, includes descriptions of complex military planning, weapon inventory and movement, and even how to deal with deserters.

Cinco de Mayo has its roots in an 1861 decision by Mexican President Benito Juárez. Facing a nation in financial ruin after two years of civil war, he suspended payment of foreign debts to the United Kingdom, Spain and France. All three nations sent warships to Mexico to seize payment, landing in Veracruz, on the Gulf Coast. The first two soon cut deals for repayment and withdrew. The French, led by Emperor Napoleon III, had more on their minds, planning to conquer the nation and establish a pro-French monarchy to rule it.

An elite French military force headed for Mexico City was stopped on May 5, 1862, at Puebla, a city about 80 miles southeast of the capital city. The Mexican forces were led by Texas-born general Ignacio Zaragoza. Working with a ragtag army, he defeated the superior French forces. The French withdrew and were forced to await reinforcements, which took nearly a year. The victory only delayed the eventual French victory (that government lasted until 1867, when it was overthrown) but it was a significant morale boost for a beleaguered nation.

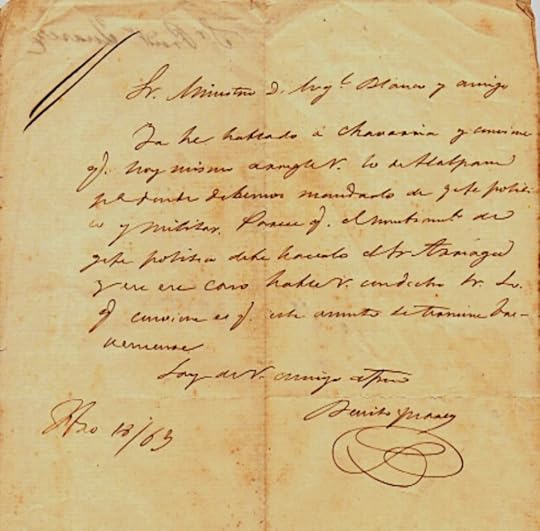

Benito Juarez letter. Latin American, Caribbean and European Division.

One of these letters from the Library’s recent acquisition was written by President Juárez while Puebla was still under Mexican control. He fired off a letter on March 18, 1863, to his minister of war, Col. Miguel Blanco, asking that a local leader, Feliciano Chavarría, be named political and military chief.

The letter — brief, handwritten — is now fragile and yellowed with age. In it, Juárez orders Blanco to take care of the issue because “what is convenient is that this matter be dealt with briefly,” according to a Spanish-language transcription. It’s the only one penned by Juárez in the collection.

But in the United States, the victory at Puebla played an important role by delaying French rule in Mexico. France had not recognized the Confederacy — no nation ever did — but was considering it. According to Clark Crook-Castan, a historian, former U.S. diplomat and vice president of the United States-Mexico Chamber of Commerce, the victory at Puebla delayed French consideration of a plan that might have helped the Confederates.

“The French hoped to circumvent the Union naval blockade by shipping long-range artillery overland to Texas and on to the Confederate armies in the east,” he said.

By the time the French gained control of the Mexican border with Texas in the summer of 1863, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had already won the Battle of Vicksburg, cutting off the Confederates’ access to weapons from the west.

The subsequent Cinco de Mayo celebrations in California and elsewhere in the Southwest were fitting because California Latinos were strong Union supporters and had helped finance Juarez’s army.

Some of the earliest American celebrations of Cinco de Mayo date back to 1866, when the Mexican Patriotic Club in Virginia City, Nevada, held a party with “grand success,” according to the Gold Hill Daily News. As the Mexican flag waved on the club’s flagstaff, the party stretched into the afternoon with celebratory gunfire, a live music band “and a good social time.”

In 1867, leaders from Mexico and the Mexican American community celebrated Cinco de Mayo at a fancy hall in California, where political speeches in English and Spanish filled the air, while “tastefully attired” ladies, mostly young and “slowing with ardent sentiment,” made up a third of the audience, according to the Daily Alta California.

In 1870, a wire-service roundup of news from San Francisco published a one line item: “The Mexicans are celebrating the anniversary of the defeat of the French at Puebla, by salutes, to-day.”

Statue of Ignacio Zaragoza Seguin in San Agustin Plaza in Laredo, Texas. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

Other articles in the Library’s Chronicling America, an online directory of American newspapers published between 1836 and 1922, detail celebrations over the ensuing decades in places like San Francisco, Santa Fe, New Mexico, and San Antonio, Texas.

A 1936 celebration on both sides of the Arizona-Mexico border made front page news in the Nogales International, while another Arizona newpaper, El Sol, published a lengthy profiles of Zaragoza in 1942, calling him a “hero” and highlighting his Texas roots.

So as you gather with friends for the 160th anniversary of Cinco de Mayo, you might have to remind some that is is not Mexican Independence Day (that’s Sept. 16). But now, as you sip a beer and munch tortilla chips dipped in guacamole, you can share a story about how, as Crook-Castan, the retired American diplomat puts it, the French defeat at Puebla had a profound impact on the Civil War and “it may well have saved the Union.”

May 4, 2022

Joan Miró’s “Makemono” Scroll — All 32 Feet of It!

A colorful section of “Makemono,” unrolled by Library staff. Photo: Shawn Miller. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

—This is a guest post by Stephanie Stillo, a curator in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Throughout his career, pioneering surrealist Joan Miró pushed the boundaries of art.

In a piece recently acquired by the Library, Miró took that experimentation to new, extreme lengths — 32 feet, to be exact.

The artwork, “Makemono,” is a colorfully illustrated silk scroll that the Spanish artist created in collaboration with French lithographer Aimé Maeght in Paris in 1956.

In the years following World War II, Miró became increasingly experimental, initiating projects that employed lithography, pochior, woodcuts, calotypes and various forms of texturizing and defacement in printmaking.

It was in this period of great creativity that Miró partnered with Maeght to create “Makemono” — a showcase of vibrant colors and technical prowess.

As its name suggests, Miró modeled the scroll after picture and calligraphic scrolls of ancient East Asian origin. Similar to traditional Asian scrolls, which present a narrative journey for the viewer, Miró filled “Makemono” with his own biomorphic characters, such as birds, eyes and the moon — an evolving visual language of figures that became the artist’s trademark throughout 20th century.

To complete the experience, the scroll is housed in a hand-carved, painted and varnished wood box, also composed by Miró.

The acquisition of “Makemono” complements the notable holdings of Miró material in the Aramont Library, a collection donated to the Library several years ago. In private hands for over 40 years, the Aramont Library consists of 1,700 volumes of literary first editions, illustrated books and an astonishing collection of “livres d’artiste” — books produced by some of the most important modern artists of the 20th century.

“Makemono” achieves a distinct blend of East and West, with an added taste of Miró’s native Catalonia — a true landmark in his own notorious experimentation with different forms of visual storytelling.

May 2, 2022

Researcher Story: Elizabeth D. Leonard

Elizabeth Leonard. Photo courtesy of the author.

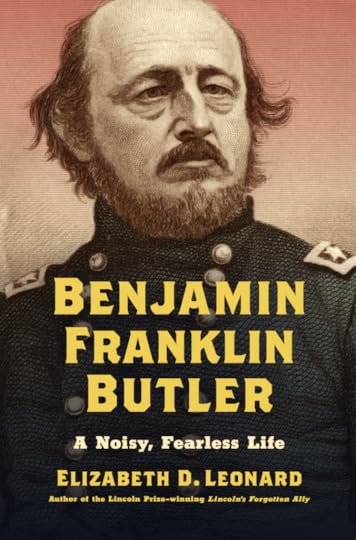

Civil War historian Elizabeth Leonard has written a number of books about the role of women on the battlefield and the social and political reverberations of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. She’s researched those books, including her soon-to-be-published title, “Benjamin Franklin Butler: A Noisy, Fearless Life,” in the Library’s Manuscript Division.

Tell us about your background and research interests.

I am a native of New York City and received my Ph.D. in U.S. history from the University of California, Riverside, in 1992.

While pursuing my doctorate, I took a particular interest in a course on the American Civil War and was struck by the absence of women in any of our readings. The assumption seemed to be that women had been irrelevant to the war effort and had not been affected by the war itself in any meaningful way. I was sure that these assumptions were false, and my desire to fill such a glaring gap in the literature led me to my dissertation topic, which became my first book, “Yankee Women: Gender Battles in the Civil War.”

All of my subsequent research has been on the Civil War (or the Civil War era), though it has moved away from a focus on women specifically.

How do you select subjects?

For an Americanist, the Civil War era is, of course, a topic of unending interest and importance. Having begun my career as a scholar of “Yankee women” who sustained the Union effort in various ways, I have generally been guided from project to project by one or more questions that remained unanswered at the time I put the previous project to bed.

In the course of my research on “Yankee Women,” I began to wonder about the experiences of women from both sides who did go into battle on behalf of their respective causes and so were planted the seeds of my second book, “All the Daring of the Soldier: Women of the Civil War Armies.”

While completing that book, I found myself questioning why so many of the “she-rebels” I encountered had avoided harsh punishment despite their often violent anti-Union behavior, while Mary Surratt had been tried, convicted and summarily executed shortly after the war as one of John Wilkes Booth’s co-conspirators in assassinating President Lincoln. One could argue that Surratt, whose involvement in the conspiracy was actually rather murky, bore the brunt of all the restraint exercised by the Union against she-rebels during the war. Researching her led me to the story of Joseph Holt — the prosecutor of the Lincoln assassination conspirators — and so on.

Leonard’s latest book, “Benjamin Franklin Butler.”

Why did you decide to delve into Butler’s story?

Anyone who studies the Civil War era in any depth eventually meets up with Benjamin Butler. A prominent lawyer and Democrat in Lowell, Massachusetts, before the war began, Butler volunteered for military service early and thus became Lincoln’s senior “political” general, in which capacity he famously established the “contraband” policy that protected slavery’s runaways from being returned to bondage.

After the war, Butler served for a decade in the U.S. House of Representatives — defending and advancing the rights of Black Americans, women and workers — and for a term as governor of Massachusetts.

Butler was also an alumnus of Waterville (now Colby) College in Maine, where I taught for nearly 30 years. Indeed, I consider him easily Colby’s most important Civil War-era alumnus, though Elijah Parish Lovejoy has traditionally gotten much more attention.

During my early years at Colby, when I still knew very little about Butler beyond the epithets that so commonly attached to his name, I envied neighboring Bowdoin College’s association with the dashing and widely celebrated Joshua Chamberlain, who not only attended Bowdoin but also taught there before leaving to join the Union army.

Then, at a conference in the early 2000s, I confessed my Bowdoin-envy to the great historian Gary Gallagher, who quite appropriately (and gently) chastised me for not digging deeper into Butler’s wartime — and indeed life — story. I eventually decided to take Gary’s advice, and here we are.

When did you first start using the Library’s collections?

I began doing research at the Library when I started work on my dissertation in 1989. I have published seven books since then, all of which have relied to a greater or lesser extent on the magnificent collections in the Library’s Manuscript Division as well as the generous assistance of its congenial and deeply well-informed staff. I am grateful!

Do you have any advice for other researchers on navigating the Library’s collections ?

Be focused. Do whatever planning you can do in advance (much information and many detailed finding aids are available online); come with a clear idea of the materials you hope to examine (but be prepared to experience both happy and frustrating surprises); and do not hesitate to avail yourself of the expertise of the gracious and generous archivists there who know the collections so well!

April 28, 2022

Frederick Law Olmsted: A Well Designed Bicentennial

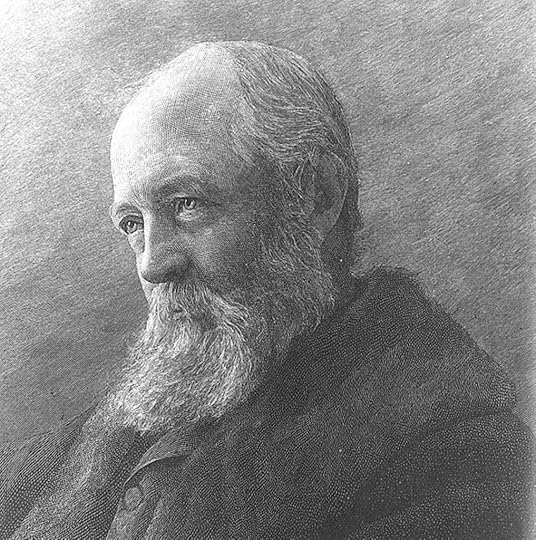

Frederick Law Olmsted. Engraved by T. Johnson; from a photo by James Notman. 1983. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Barbara Bair, a historian in the Manuscript Division.

This month, the Library is recognizing this week’s bicentennial of the birth of writer, administrator and landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of the U.S. Capitol grounds and public parks and spaces around the country. Activities include an Olmsted Bicentennial exhibit in the Jefferson Building and a series of By the People crowdsourcing transcription challenges for online volunteers.

The Library holds the largest collection of manuscript materials in the nation related to Olmsted’s long career, as well as the records of the 20th-century successor firm operated by his sons.

The Manuscript Division holds both Olmsted’s personal papers and the records of Olmsted Associates. The landscape architecture firm based in Brookline, Massachusetts, was operated by Olmsted sons Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. and John Charles Olmsted, and featured many talented associates. These collections are digitized and available online.

The bicentennial exhibit charts Olmsted’s life from his youth through modern reinterpretations of the public parks he designed. The five-case display is on view on both sides of the Great Hall through June 4. It features items from the Manuscript Division, the Prints and Photographs Division and the general collections in combination with reproductions of drawings and photographs from the National Park Service’s Olmsted Archives at the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site in Brookline.

A crowd lunches during a 1907 May Day party in Central Park, one of Olmsted’s most famous projects. Prints and Photographs Division.

In April up to the anniversary on the 26th, the Library’s By the People crowdsourcing transcription program also hosted a weekly series of special “By Design: Frederick Law Olmsted and Associates” campaign challenges. Based on the subject file in the Olmsted papers manuscript collection, the challenges gave online volunteers a chance to get up close and personal with Olmsted. The volunteers transcribed select printed and handwritten materials from his papers or items from various geographical regions that were the focus of Olmsted’s many projects and proposals.

Olmsted gained experience growing up in the woodlands of the Connecticut Valley and on trips in New England and New York, including to Niagara Falls and Lake George. He widened his observations through travels as a young man to England, Europe and China. As a journalist and travel writer in the fraught decade before the Civil War, he published observations of park and garden systems internationally and wrote of the economy and sociology of the slaveholding American South and Texas.

His breakthrough as an innovative planner of public parks came just before the war, when he partnered between 1857 and 1861 with architect Calvert Vaux to implement their award-winning design for Central Park in Manhattan. After the war began, Olmsted served as general secretary for the U.S. Sanitary Commission and helped devise a system of “floating hospital” ships to transport the ill and wounded of the Union Army.

After the war, he proposed projects located in all regions of the country and parts of Canada, emerging as the foremost spokesperson for the public parks movement. His treatises on the planning, access and use of public parks influenced the creation of the Emerald Necklace system of greenways in Boston and the formation of Yosemite National Park by an Act of Congress in 1890. The Olmsted legacy reached into Canada with Mount Royal Park, and was manifested at Niagara Falls, in the Stanford and University of California, Berkeley, campuses in California and Gallaudet University in the District of Columbia.

He was an important mentor to his son, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and step-son, John Charles Olmsted. He also mentored a stream of young associates, most affiliated with Arnold Arboretum and Harvard University. After his death in 1903, the work of the Olmsted firm was carried on into the next half-century from his Fairsted home and headquarters in Brookline. Associates of the firm included Edward Clark Whiting, who was responsible for much of the firm’s planning for Rock Creek Park in Washington, D.C.

The Library joins the American Society of Landscape Architects, the Cultural Landscape Foundation, the National Association for Olmsted Parks, the National Park Service, local Olmsted park conservancies and many other institutions and organizations across the nation in recognizing the ongoing impact and history of Olmsted’s theories of public parks and two generations of Olmsted family landscape designs.

April 27, 2022

Ulysses S. Grant: 200th Birthday

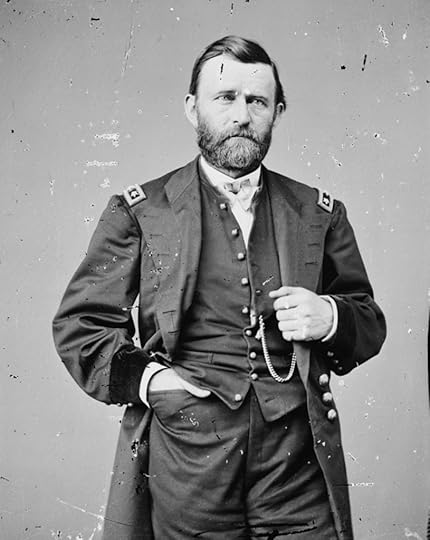

General Ulysses S. Grant. Brady-Handy photograph collection. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Michelle Krowl, a historian in the Manuscript Division.

“In June 1821 my father, Jesse Root Grant, married Hannah Simpson. I was born on the 27th of April, 1822, at Point Pleasant, Clermont County, Ohio.”

In his typically concise way, General Ulysses S. Grant, 18th president of the United States, recounted in his manuscript memoirs his own start in life. His unremarkable birth, however, was the beginning of a remarkable life that would see him more than once plummet to the depths of despair and rise to the pinnacle of success. What better way to commemorate his 200th birthday than to explore his extraordinary life through his papers at the Library?

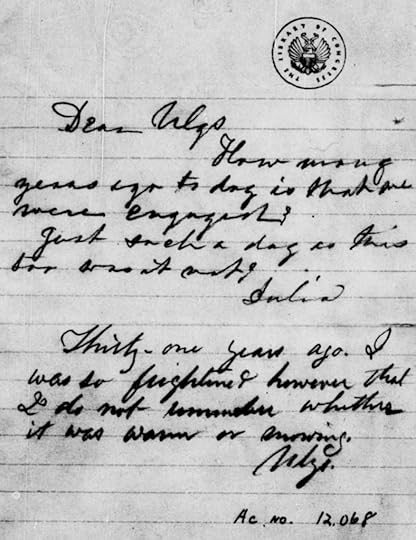

The most personal of Grant’s papers are the letters to his wife, Julia Dent Grant. While stationed in St. Louis, Missouri, after his graduation from the United States Military Academy in 1843, Grant visited the nearby family home of his West Point friend, Frederick Dent. There Grant met Fred’s sister, Julia, and fell helplessly in love. The couple quietly became engaged in May 1844, although “Ulys” would later admit that he had been “so frightened” on the day he proposed that he could not “remember whether it was warm or snowing.” Grant’s military postings and the Mexican War (1846-1848) contributed to their long engagement. He wrote faithfully when they were apart, sending flowers he picked on the bank of the Rio Grande River, sharing his observations of the war in Mexico, expressing his devotion to her, and always urging her to write more often.

Ulysses Grant note to his wife, Julia, on May 22, 1875, on their 31rst wedding anniversary. Manuscript Division.

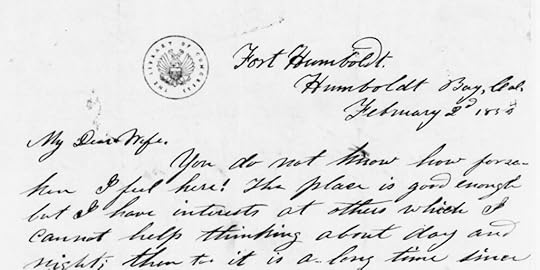

The couple finally married in 1848 and shared several happy years living together at military posts in Michigan and New York. In 1852, the army sent him to outposts in California and Oregon. The devoted family man missed his wife and their two young sons. An air of desperation crept into his letters home. “You do not know how forsaken I feel here!” he wrote in 1854. “How very much I want to see all of you.” Not being able to “endure this separation” any longer, Grant resigned from the military in April 1854 and returned to St. Louis. Although reunited with his family, he struggled to find steady employment as a civilian. The name Grant gave to a family farm summed up the bleak years just before the Civil War: Hardscrabble.

“My Dear Wife…” Fort Humbolt, California, February 2, 1854. Manuscript Division.

At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Grant returned to the U.S. Army. His series of battlefield successes eventually elevated him to the highest rank of lieutenant general. Despite his increasing responsibilities, he frequently wrote to his wife when she could not join him at the front. In a short but endearing letter on June 7, 1864, for example, the general-in-chief of the Union army thoughtfully enclosed a lock of hair she had requested. Before sending his usual “love and kisses for you and the children,” he joked that “war will get to be so common with me if this thing continues much longer that I will not be able to sleep after a while unless there is an occasional gunshot near me during the night.”

On the professional side, Grant’s military correspondence from 1861 to 1869 is reflected in volumes of Headquarters Records. The content encompasses both the mundane and momentous, including Grant’s notorious December 1862 order expelling Jews from the Department of the Tennessee (which was quickly revoked by President Abraham Lincoln) and the negotiations resulting in Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox in April 1865.

Cartoon of Grant in clothing of various countries he visited on global travels — but always shown with his familiar cigar. Manuscript Division.

After completing two terms as president in 1877, the Grants embarked on a trip that ultimately took them around the world. He learned about foreign governments, the people of other nations, and met Americans abroad, while she recalled in her memoirs the entertainment, sightseeing, and shopping opportunities. The correspondence Grant received between 1877 and 1879 reflects the countries to which he traveled and honors accorded him. A scrapbook of newspaper clippings provides readers a further glimpse into his international travel experiences.

A section of Grant’s insert in his manuscript expressing regret for ordering a disastrous final assault at Cold Harbor in 1864. Manuscript Division.

Grant suffered two crushing blows in 1884.

First, he went bankrupt after the collapse of a Ponzi scheme in which he had invested. Second, and far worse, his persistent throat pain was diagnosed as cancer of the tongue. Fears for his family’s solvency prompted him to write his memoirs, of which his handwritten pages reside in the Grant Papers. The manuscript pages reveal Grant’s writing process, including corrections and additions, notably the later insertion of a section beginning, “I have always regretted that last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made.” The nation went on a death watch as Grant raced against time to complete the manuscript. Children wrote encouraging letters to him. Unable to speak at the end, Grant wrote notes to visitors to the Mount McGregor, New York, cottage in which spent his last weeks. He died in July 1885, just days after completing the memoirs that would earn both critical and commercial success.

From the highest highs to the lowest lows, Grant’s story is always compelling.

April 25, 2022

The Gorgeous Jazz Age Photography of Alfred Cheney Johnston

Legendary actress Mary Pickford poses for Alfred Cheney Johnston in 1920. Prints and Photographs Division.

In the Jazz Age, when the hot new music and racy new sensibilities were sweeping across pop culture, it perhaps reached its zenith in the Ziegfeld Follies. The Broadway musical revues produced by Florenz Ziegfeld Jr., began in 1907 and ran for more than two decades at the New Amsterdam Theatre. The shows featured dance numbers, comedy acts and shapely young women in skimpy outfits. The shows, particularly those at midnight, became legendary for their style, pizzazz and sex appeal.

The court photographer for the Follies, Alfred Cheney Johnston ̶ who later donated more than 200 of his photographs to the Library ̶ captured the era and helped create the celebrity glamour shot, soon to become an industry standard. These were soft-focused, well-composed, sepia-toned portraits with Old Master lighting. In so doing, Cheney also became one of the first celebrity photographers, and certainly one of the most famous of the day.

“I try to make not just a photograph of a girl’s face and figure but one of her personality as well,” Johnston told a newspaper columnist in 1928. “I suit everything to the personality of the person whose picture I’m making. Lights, background, composition – everything.”

Barbara Stanwyck, who would go on a long career in film and television, began her career as a Ziegfeld showgirl in the 1920s. Photo: Alfred Cheney Johnston. Prints and Photographs Division.

Stars flocked to him. Mary Pickford. Clara Bow. Helen Hayes. John Barrymore. Barbara Stanwyck. Dorothy and Lillian Gish. Marilyn Miller. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. Helen Hays. Mae Murray. Billie Dove.

“His spellbinding portraits … adorned a vast array of newspapers and magazines of the era,” writes author Robert Hudovernik in “Jazz Age Beauties: The Lost Collection of Ziegfeld Photographer Alfred Cheney Johnston,” which draws in part on the Library’s photographs. The book was published in 2006 and reissued late last year. “They dramatically contributed to the adoration of stars by their fans, who worshipfully pasted them in their scrapbooks or tacked them onto their bedroom walls.”

Alfred Cheney Johnston, circa 1921. Photo: Unknown, Public domain, Wikipedia commons.

At the height of Johnston’s career, he sometimes charged $500 to $1,400 for a set of a dozen prints, the equivalent of $14,000 to $40,000 today. In these celebrity shots, and in his stylish, high-end photos for advertising campaigns, he created a sensuous atmosphere. Many stars (and private clients) posed nude and semi-nude, with furs and gowns and scarves draped just so. The oriental rugs and draperies in the background, the ornate furniture, the formal poses, the sepia-toned images were all designed to make the photographs look like classic paintings from an earlier era.

The twist, Hudovernik says, is that he “jazzified” them, with portraits of “modern women in the ’20s.”

This wasn’t by accident; Johnston came from a wealthy New York banking family and studied art as a student. His wife, Doris, was a painter. He was a classy, upscale sort, friends with Norman Rockwell, Ansel Adams and and Charles Dana Gibson, the last of whom had created a standard of female beauty a generation earlier with his “Gibson Girl” sketches.

Johnston’s studio was in the Hotel des Artistes, a luxury co-op on the Upper West Side. He shot with a large view camera on a tripod, which produced a large glass-plate negative. He often painted the background onto the negatives.

“Jazz Age Beauties,” by Robert Hudovernik.

As Johnson’s fame grew, he became regarded as a new arbiter of female beauty. In 1928, he wrote a series of articles for a newspaper wire service about different kinds of classic female archetypes. One was headlined, “Typical Girl of U.S. Blends All Styles of Beauty.” In the article, Johnson dispensed step-by-step makeup advice: “When face rouge is used, it should be applied to the center of both cheeks, skillfully toned from light to dark, and just the merest speck to the center of the chin.”

The Follies came to an end in 1931 and Zeigfeld died in 1932. Still, there were Broadway revivals during the 1930s and a film, “The Great Ziegfeld,” won the Oscar for Best Picture in 1938. But Johnston’s star began to fade by World War II, when he left New York for a rural Connecticut studio, rejecting Hollywood. Times were changing, but he kept to his ways and big box camera, which began to seem not so much classic as old-fashioned. By the time he died in a 1971 car crash at age 86, he was a widower living alone; he and Doris had no children. Hudovernik writes that only two people attended his funeral.

Fine-art connoisseurs never took to his work – too focused on celebrity, too commercial – and thousands of his prints, left to no museum or established collection, began to be pieced out and sold off in various sales and auctions. Hudovernik discovered Johnston’s work in the late 1990s and spent more than five years of research before publishing the first edition of his book in 2006. Cheney’s growing popularity — his prints now routinely sell for a few thousand dollars each — led to the book’s reissue in 2021.

The Library’s collection, featuring stars from the stage and film and from advertising campaigns, were hand-selected by Johnston decades earlier, Hudovernik says, when his life’s work was intact.

“It’s a gem of a collection,” he says. “These are prints he picked out as some of his best work.”

Actor Tyrone Power. Photo: Alfred Cheney Johnston. Prints and Photographs Division.

His photographs still catch the eye; several of his signed prints were pulled out for display on a recent afternoon in the Prints and Photographs Division. Framed in brown mattes, they were a portal to a previous era’s ideals of sensuous beauty.

Julie Newmar, the legendary stage and screen actress (she was the first Catwoman in the original “Batman” TV series), posed nude for Johnston in the 1950s. Her mother, a Follies dancer, had posed for him decades before.

In the introduction to Hudovernik’s book, she remembers him as “distinguished,” and that his studio, even during the mid-century, like a time capsule from the Jazz Age. She lovingly recounts his legacy as a “treasure trove of magnificent photographic images that capture (his subjects) individual incandescence, as well as the energy and glamour of the dizzy, gilded era of which these stars were born.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

April 21, 2022

How “It’s a Small World” Turned Into One of The World’s Most Played Songs

The National Recording Registry badge for “It’s a Small World.” Graphic: Ashley Jones.

The National Recording Registry has inducted plenty of popular songs over the years, but few come close to “It’s a Small World,” the theme song to the Disney theme park ride of the same name, as it has been played more than 50 million times since its 1964 debut.

One of 25 songs added to the NRR this year, the little song about world peace was likely the most–played song in global history until the advent of streaming services, where worldwide views and listens can soar into billions of plays. “Small,” though never a radio hit, has played constantly at the Disney theme park rides of the same name, over and over again, all day long, as just about every parent can attest.

“People either want to kill us or kiss us,” laughs co-writer Richard Sherman, now 93, in a recent phone interview from his California home. His brother and songwriting partner, Robert, died in 2012.

They pair didn’t intend for “Small” to become an earworm of historic proportions. The Oscar-winning pair wrote much of the Walt Disney songbook of the 1960s, turning out the music for film hits such as “Mary Poppins,” “The Jungle Book,” “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang,” “Winnie the Pooh,” “The Happiest Millionaire” and “Tom Sawyer.” For good measure, they wrote “You’re Sixteen,” a hit in 1960, which then went to No. 1 in 1974 for Ringo Starr.

The songs from their Disney movies, including “I Wan’na Be Like You,” “Chim Chim Cher-ee” and “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious,” became almost universally known to children of the 1960s and ’70s. Today, “Be Like You,” from “The Jungle Book,” has been viewed more than 64 million times on YouTube alone. Disney eventually renamed its Soundstage A for the pair. When their sons filmed a documentary about them in 2009, “The Boys: The Sherman Brothers’ Story,” the list of stars and studio executives who turned out to be interviewed seemed endless: Julie Andrews, Angela Lansbury, Dick Van Dyke, John Landis and Samuel Goldwyn Jr., to name a few.

“We loved to write songs,” Sherman said. “Our father was a great songwriter. It was just a natural thing for us.”

Indeed, their father, Al, whose family had fled Jewish persecution in Ukraine (then part of the Russian Empire) had an impressive career in the first half of the 20th century. He wrote or co-wrote hundreds of songs for Broadway, Tin Pan Alley and film.

Robert and Richard were born in the 1920s, growing up in the Los Angeles area. Urged by their father to work together in music, they began writing pop songs and were working directly for Walt Disney himself by the early 1960s.

Their film scores were immediate hits. But in 1964, “Small” was just a simple ditty the brothers banged out for what they thought was to be a short-term exhibit at the 1964-65 World’s Fair in New York. The fair’s theme was “Peace Through Understanding” and the Disney exhibit was part of a salute to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

The exhibit was a water ride that would take visitors through models of different nations. Animatronic dolls, portraying children from around the globe, would sing about world peace. The first idea for the music — the dolls singing different national anthems — didn’t work. So, while the project was still being designed, Disney assigned the Shermans to come up with a kids’ song for the ride.

“Just don’t preach,” Sherman remembers Disney telling them.

The context of the era, mostly lost on listeners today, was the Cold War. Threats of atomic bombings by the Soviet Union dominated the national mindset. Schoolchildren practiced duck-and-cover drills; the “Fallout Shelter” sign — orange-and-black with three inverted triangles set inside a black circle — became common on sturdy buildings. The Cuban missile crisis in October 1962 elevated the situation to a fever pitch. (The second line of “Small” is, “It’s a world of hopes and a world of fears.”)

“It came pretty easily,” Sherman remembered. “We didn’t sweat blood over it.”

They previewed it for Disney, he liked it and that seemed that. Then, not knowing of Disney’s plans to create multiple theme parks (only one existed at the time) and that “Small” was going to be a theme park attraction after the World’s Fair was over, the pair mentioned during a brief car ride that they planned to donate the song’s copyright to UNICEF. It seemed like a symbolic gesture, Sherman said, as the World’s Fair would come and go and so would the song.

“He stopped the car, turned and said, ‘Don’t you give that away! That’s for your grandkids! It’ll put them through college!’ ” Sherman laughed. “He was right. It’s our biggest copyright by far.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

April 18, 2022

Motown’s Songwriting Stars and “Reach Out I’ll Be There”

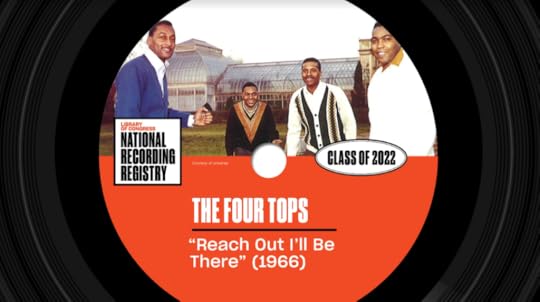

“Reach Out I’ll Be There” by the Four Tops was inducted into the 2022 National Recording Registry. Graphic: Ashley Jones.

Lamont Dozier grew up in the last days of Detroit’s Black Bottom, the rough-hewn neighborhood just north of downtown that was adjacent to the jazz clubs and nightlife of the Paradise Valley section of the city.

By the early 1960s, he and his songwriting partners, brothers Brian and Eddie Holland, were in their early 20s. In a furious three-year span, they helped rewrite the city’s history as the home of Motown, the Black-owned record label that reshaped American pop music.

Holland-Dozier-Holland songs, recorded by acts including the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, the Four Tops, the Isley Brothers and Martha and the Vandellas, topped the charts and defined the Motown Sound. “Heat Wave,” “Baby Love,” “I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch),” “Stop! In the Name of Love,” and “This Old Heart of Mine” were just some of the hits they wrote between 1964 and 1966.

“Reach Out I’ll Be There,” inducted into the 2022 class of the Library’s National Recording Registry, was a smash for the Four Tops in 1966. The H-D-H trio wrote it, like their other hits, in an upstairs office at Motown Studios, a converted two-story house on West Grand Boulevard. They worked from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., much like the auto factory workers in town. About the only thing in the room was a piano.

“It was a fun time, like kids playing in a playground,” Dozier, 80, said recently in a phone interview from his California home. “Everything we touched turned to gold.”

Life certainly didn’t start out that way for Dozier. Like nearly all of his Motown peers, he grew up in racism-based hardship. Blacks had fled the South for better-paying northern manufacturing jobs in the Great Migration during the first decades of the 20th century. But Detroit, among other destinations, proved to be “the promised land that wasn’t,” in the words of Rosa Parks, who fled Alabama for Detroit.

The new arrivals were forced into downtrodden neighborhoods, such as Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, where living conditions were segregated and often harsh.

“Whatever you called it, it was the ghetto,” Dozier remembers.

But jazz, the pop music of the day, had created a class of Black musicians who recorded, toured and made good money. In Detroit, Black kids grew up on that music. Many of them, like Dozier, also had relatives who played classical piano. Combined with the gospel played every Sunday in churches, a fusion emerged that would create soul, rhythm and blues and greatly influence rock and roll.

Dozier, who took to the piano after his aunt would come to their house and play Chopin and other classical composers, jumped into the local music scene when he was a teenager. He got his breakthrough from Berry Gordy, another musically minded, ambitious entrepreneur who was a few years older.

Soon after Gordy established Motown, Dozier began teaming with the Holland brothers. He and Brian Holland composed the music, sitting side by side at the piano. Eddie Holland added lyrics. They’d take the results to any number of the acts — many of whom were teenagers — who were constantly flowing through the studios.

They had their first national hit in 1963 with “Heat Wave,” recorded by Martha and the Vandellas. The next year, they emerged from their office with a song called “Where Did Our Love Go.” Dozier had composed it with the Marvelettes in mind, but they turned it down. The Supremes, who did not yet have a hit, reluctantly agreed.

It was not a happy recording session. In a 2020 interview with American Songwriter, Dozier said that he and lead singer Diana Ross were “throwing obscenities back and forth” about the key in which the song was to be recorded, and the other two singers did not like his complex arrangements for the backing vocals. They eventually agreed, he said, to just sing, “baby, baby.”

The song became the Supreme’s first No. 1 hit. (It was inducted into the registry in 2015.) The Supremes would go on to become one of the most successful acts in American music history, with 12 No. 1 songs. H-D-H wrote 10 of them.

Dozier remembers it all now with pride, saying it was remarkable how quickly the songs came to the trio in the little upstairs room.

For “Reach Out,” they were partly inspired by Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone,” in which Dylan half sang, half shouted the title refrain. They put “Reach Out” in the highest reaches of lead singer Levi Stubbs’ range, forcing his vocals to sound rough and urgent. The galloping percussion sound at the beginning of the song, which helped make it so instantly identifiable, came from musician and producer Norman Whitfield hitting a modified plastic tambourine — they removed all the jingles before the recording session.

“Brian and I came up with the melodies on the piano, sitting side by side, he would start ‘danh danh da danh’ and I’d push him over a bit and I’d play the next bar,” Dozier said. “Eddie would listen and get an idea of what should be said. The music and lyrics would come at the same time. The collaboration was something. The energy was just flying around in the room.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

April 15, 2022

How Alicia Keys Got Her “Hit a High Note” Nickname

Alicia Keys talks about recording her first album in her Harlem apartment.

We caught up with Alicia Keys recently, talking about her electrifying 2001 debut album, “Songs in A Minor,” and its induction into the 2022 class of the National Recording Registry.

She started writing the first songs on it at age 14 and released it to great fanfare at 18. She described her influences on the album as a “fusion of my classical training, meshed with what I grew up listening to,” which included the jazz from her mother’s record collection, along with the classic R&B and hip-hop that was prevalent in her New York City neighborhood.

What is about that set of songs that has resonated with listeners for two decades?

“It was so pure,” she said. “You felt the truth that was coming from me. I think that the New Yorkness in me was definitely a new energy. People hadn’t quite seen a woman in Timberlands and cornrows and really straight 100% off of the streets of New York performing classical music and mixing it with soul music and R&B and these songs that had big choruses and meaning … and people could find themselves in it.”

She was a perfectionist for the sound she wanted, turning her apartment — a sixth-floor walkup on 137th Street in the heart of Harlem — into an improvised studio. Her all-out vocals, belted out night after night, led to neighborhood fame long before the songs found their way to radio stations.

“We took the one bedroom that we had and turned it into a studio,” she said. “The closet was my little booth. I figured if we hung blankets on it, it would like create the sound we needed. The bed was still in the room. There was a bunch of equipment all around… I remember people on the street when I would come home, they would be calling me ‘Hit a High Note” because all night they heard me singing at the top of my lungs in this little Harlem apartment with the windows open because it was burning hot. So that became my little nickname on the block, ‘Hit a High Note.’ ”

The album would create a sensation due to her songwriting, vocals and piano playing. “Fallin’” was a No. 1 smash, with “A Woman’s Worth,” “Rock Wit U” and her take on Prince’s “How Come You Don’t Call Me Anymore” getting significant airplay. It’s an album that became part of the national soundtrack that year, a postcard from the era, that is now preserved in the national library.

Alicia Keys National Recording Registry badge. Graphics: Ashley Jones.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers