Library of Congress's Blog, page 32

June 17, 2022

The Genius of Cameroon’s Sultan Ibrahim Njoya

It was the late 19th century in western Africa. European nations had just carved up the continent’s resources (and people) in the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, the major chapter in what historian Thomas Pakenham described, in a term commonly used for the era, as the “scramble for Africa.” In the ensuing three decades, European colonial powers took control of almost 90 percent of the continent.

In the interior of a territory the German occupiers called Kamerun, a sultan named Ibrahim Njoya held sway over the kingdom of Bamum (also spelled Bamoun). He was the most recent in a line of a royal family that had ruled the grasslands region for hundreds of years.

He was a remarkable man, a polymath scholar, probably the most visionary of all the rulers of his kingdom.

Born in the midcentury, Njoya grew to be a thoughtful leader who melded the modern techniques of the colonizers with the wisdom of his ancestors, taking power in the late 1880s in his capital city of Foumban. He oversaw the first surveyed map of his kingdom, called the Lew Ngu, or the “Book of the Country.” He wrote, with assistance from several scribes, the first history of his people. He created his own spoken and written language and built dozens of schools to teach it. Over time, he developed a unique religion that brought together Bamum’s spiritual practices with Islam and Christianity.

The map of Bamum that Sultan Njoya commissioned. The text is in the language he created. Geography and Map Division.

He built a mansion that still stands today as a museum, and was a devout patron of education and the arts. His half first cousin – who shared his name – became an accomplished artist and is now regarded as the nation’s first prominent cartoonist.

Today, the Library preserves several of Njoya’s achievements, including several of the maps and sketches he commissioned, along with examples of his language. There are also dozens of photographs from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, showing men on horseback, women with unique hairstyles, buildings with elaborate carvings, and Njoya in variety of formal settings. (Most of these were purchased from an arts dealer within the past decade.) Together, they form a window into the intellectual and artistic life of African populations before they were obliterated by colonialism.

“One of the many things we do is provide research and stories that are not widely known,” says Lanisa Kitchiner, chief of the African and Middle Eastern Division. “One of those is of Sultan Ibrahim Njoya. In creating (his maps, language and alphabet), he preserved not only a snapshot of his kingdom’s physical boundaries when European colonialists were erasing them, but also a picture of his nation’s hopes, dreams and aspirations.”

But Njoya was born in the wrong era for self-determination in that corner of the world.

Locked inland, with no way to match German military or economic might, he thought the best path forward was one that did not interfere with German plans. Though a man of modern aspirations, he also hewed to his ancestral practice of polygamy, claiming hundreds of wives and more than 100 children. This bifurcated approach to lifestyle and governance had its risks, most notably from more traditional military men in his own region, who did not endorse his cooperative approach to colonizers.

By the time World War I came and went, leaving the French in charge of the region, Njoya was running out of room to maneuver. French colonialists sidelined him in 1931. He died two years later, though one of his sons would later take regain power, and the family remains influential today.

Still, Njoya’s reign during a period of great upheaval and transition managed to preserve his kingdom’s remarkable history for the ages.

Blog tagline: Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 6, 2022

My Job: Mark Horowitz, from Broadway to the Beltway

Mark Horowitz (l) and Lin-Manuel Miranda (r) looking over Jonathan Larson’s collection at the Library.

Mark Horowitz in the Music Division works with some of the biggest names in musical theater.

Describe your work at the Library.

I’m a senior specialist in the Music Division’s acquisitions and processing section, where my specialty is American musical theater. I acquire collections for the Library — these have included the papers of Howard Ashman, Adam Guettel, Marvin Hamlisch, Jonathan Larson, Hal Prince, Jeanine Tesori and a promised bequest from Stephen Sondheim.

I process special collections — sorting, organizing, identifying, foldering, labeling and writing finding aids. I provide reference. And I get to do special projects, such as co-producing concerts and exhibits and conducting interviews for the Library’s website — including interviews with Sondheim, Burt Bacharach and Randy Newman.

Mark Horowitz. Photo: Shawn Miller.

What are some of your standout projects?

Producing a 70th birthday celebration concert for Sondheim. Our cast included Nathan Lane, Audra McDonald, Marin Mazzie and Brian Stokes Mitchell. It included a newly orchestrated concert version of his “The Frogs,” which was then recorded for the first time and led to an expanded version of the show premiering on Broadway. That concert included a segment of Sondheim’s “songs he wish he’d written,” the complete list of which was then published in the New York Times and led to a series of Barbara Cook “Mostly Sondheim” concerts and recordings.

In 2018, I received the Kluge fellowship reserved for a Library staff member. My project allowed me for one year to seek out, read, review, select and transcribe correspondence from and to the lyricist, librettist and producer Oscar Hammerstein II. Among the shows Hammerstein wrote were “Show Boat,” “Oklahoma!,” “Carousel,” “South Pacific” and “The King and I.” His correspondence represents a who’s who of show business, but he was also deeply involved in social issues, including working with the NAACP. I ended up transcribing over 4,500 letters. The plan is that these transcripts, accompanied by scans of at least some of the originals, will become a Library website. I believe these letters will be a revelation to many and prove a vast source for research.

What have been your most memorable experiences at the Library?

Making Stephen Sondheim cry when I showed him Gershwin’s manuscript for “Porgy and Bess.” Doing a show-and-tell for Angela Lansbury, during which she sang “Beauty and the Beast” for me, first as Ashman and Alan Menken had performed it for her (up-tempo), then the way she insisted on singing it (as a ballad).

What are your favorite collection items?

There are hundreds, but the first that comes to mind: Oscar Hammerstein’s lyric sketches for “My Favorite Things” (“Riding down hill on my big brother’s bike/These are a few of the things that I like”) and “Do-Re-Mi,” where for several pages he gets stuck on the line “Sew — a thing you do with wheat.” Larson’s lyric sketches for “Seasons of Love,” where you see him do the math that calculates there are 525,600 minutes in a year. A letter from George Bernard Shaw to a 19-year-old Jascha Heifetz, cautioning him to play something badly every night instead of saying his prayers so as not to provoke a jealous god.

Lin-Manuel Miranda tweets an acknowledgement to Horowitz on the release of “tick, tick … BOOM!”

June 3, 2022

Einstein Fellow: Lesley Anderson

Lesley Anderson.

Lesley Anderson is a 2021–22 Albert Einstein Distinguished Educator at the Library. The fellowship program appoints accomplished K–12 teachers of science, technology, engineering and mathematics to collaborate with federal agencies and congressional offices to advance STEM education. Anderson teaches high school math, chemistry, biology and environmental science in San Diego.

As a STEM teacher, what resources at the Library have captivated you?

Beyond the obvious collections, such as the Wright Brothers or the Alexander Graham Bell papers, there are many artifacts that can be used in a STEM classroom. I particularly loved working on a free-to-use photo set of natural disasters to be featured on the Library’s homepage this summer. I also enjoyed compiling a related primary source set for teachers that will appear on the Library’s site for teachers.

I found so many interesting interdisciplinary connections that enable students to consider not only the scientific explanation for the cause of a disaster, but also the response to it and potential future mitigation.

How has the pandemic affected your fellowship?

The first half of my fellowship was all remote, which made it challenging to learn about how the Library is structured and how all of the departments work together. In the past two months, however, I’ve had the privilege of coming into the office twice a week, and I’m learning even more about the Library in different ways. It’s almost like having a second fellowship.

You’ve worked with federal agencies previously doing hands-on science.

I started my first teacher-research experience with NASA at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, looking at photocopies of old records of Arctic expeditions to compile an archive of historical sea ice thickness measurements.

Then, I further fueled my enthusiasm for polar science with a PolarTREC expedition to the South Pole in 2017, retracing the steps of polar explorers who risked everything to be the first to study the Arctic and Antarctic.

Coming to the Library, I was immediately drawn to searching for polar science artifacts in the collections. I could barely hold back my excitement when I had the chance to sit in a room with materials from explorers and expeditions — Admiral Byrd’s scrapbook with pictures from Antarctica, the Frederick Cook papers and Finn Ronne’s notebook from the Byrd Antarctic expedition. Years ago, at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, I never would have guessed that I would have the opportunity to hold the original copies of those old photocopied notebooks in my very own hands.

Even though I have conducted research with federal agencies in the past, I came to the Library with an open mind and the intention to learn as much as I could from the experts in the field so I can take that back into the classroom with me.

How will your experience at the Library inform your classroom teaching?

Spending a year at the Library has renewed my passion for lifelong learning and curiosity. When I look at a primary source, I immediately begin asking questions and find myself starting to “go down the rabbit hole” as I begin researching other related topics to answer my own questions. I hope that I can inspire that authentic inquisitive process, reflected in the scientific method, with my students when I return to the classroom.

How are you sharing the resources you’ve discovered?

I’ve enjoyed writing blog posts, publishing articles, hosting webinars and presenting at conferences to share the word about how to use primary sources in STEM classrooms. My posts are searchable on the Library’s blog for teachers, and my webinars will be available on the Library’s website in coming months.

What do you want STEM educators to know about the Library?

I hope that STEM educators can see the Library as I now do — the site of a rich collection of STEM resources, including curated primary sources that are ready to be used in K–12 classrooms. Primary sources can provide new access points to phenomena that may engage students who are typically disinterested in STEM topics. Additionally, primary source analysis can be a tool to enable students to think critically about a resource and incorporate science and engineering practices into their interdisciplinary learning.

For more information about this program, visit the Library’s Teacher in Residence Programs page.

June 1, 2022

“Top Gun” — The Library of Congress Keeps Receipts

Tom Cruise, the first time around, in a publicity still from “Top Gun.” Photo: Paramount Pictures.

“Top Gun: Maverick” took your breath away, did it?

The sequel to the 1986 blockbuster is, if anything, a bigger hit than the original. The film, in which Tom Cruise reprises his role as Pete “Maverick” Mitchell, took in a Memorial Day weekend record of an estimated $156 million at the box office. Fighter jets, “Danger Zone” and popcorn. Good times.

Your friendly national library is making sure this cinematic love affair is preserved on several fronts, particularly with the first film. We were mildly surprised at just how many.

First, the Library’s National Film Registry’s class of 2015 added the original to the the Library’s list of “culturally, historically or aesthetically” important films worthy of national preservation. Second, it turns out the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center has the original 35mm movie film print. The real reels! Third, the Music Division has the commercial sheet music for the film’s songs, which might be expected, but also (unexpectedly) has the gold-record award given to Tom Whitlock for cowriting, among other hits on the soundtrack, “Take My Breath Away.”

The Library’s 35mm prints for “Top Gun” in the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center. Staff photo.

When the film was added to the registry, the Library’s film staff noted its pop-culture indulgences in their official summary, but also that it “actually comprises a deft portrait of mid-1980s America, when politicians promised ‘Morning in America Again,’ and singers crooned ‘God Bless the U.S.A.’ The U.S. Navy, for one, did not complain: Applications to naval aviation schools soared in part as a result of this relentless, pulsating film famed for its vertiginous fighter-plane sequences.”

They also noted that director “Christopher Nolan has highlighted ‘Top Gun’ for the clear influence of the film’s celebrated visual style on future filmmakers.”

Whitlock’s songwriting contribution, part of the Library’s collection from the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers, shouldn’t be overlooked. The song, which he wrote with the influential producer Giorgio Moroder, won both an Academy Award and Golden Globe for Best Original Song.

The movie, and the song, really did catch the nation’s imagination in the 1980s, and that’s the kind of thing the Library was meant to preserve.

Tom Whitlock’s framed gold record award for “Take My Breath Away,” the love song from “Top Gun.” Staff photo.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 31, 2022

The Eye of Jazz: The Photographs of William P. Gottlieb

New York City’s 52nd Street on a rainy night in July 1948. Photo: William P. Gottlieb. Prints and Photographs Division.

This story first appeared in the Library of Congress Magazine.

One of the world’s great collections of jazz photos got its start with a questionable piece of pork and a bad case of trichinosis.

The victim, a Lehigh University student named William P. Gottlieb, was laid up for some time, and his friend Doc would come by to help him pass the hours, bringing along jazz records from his collection.

Gottlieb, no fan of the genre beforehand, was hooked.

After graduating in 1936, he accepted an advertising job at The Washington Post for $25 a week and, wanting to earn extra money, persuaded the editors to let him write a weekly jazz column for an extra $10.

They agreed but told Gottleib he’d have to take his own photos, so he bought a Speed Graphic camera and taught himself to use it.

Working for the Post and later for DownBeat magazine over a 10-year span, Gottlieb captured the era’s greatest musicians in their element — Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and countless others. He left jazz journalism and photography in 1948, when he was just 31. He went into the educational film business, wrote some children’s books and was a serious amateur tennis player. He died in 2006, at age 89.

In 1995, the Library purchased Gottlieb’s collection — some 1,600 negatives and color transparencies, plus exhibition, reference and contact prints. In 2010, the photos entered the public domain, in accordance with Gottlieb’s wishes.

The legendary Charlie Parker playing at the Three Deuces in August 1947. Photo: William P. Gottlieb. Prints and Photographs Division.

Gottlieb was paying for his own film and flashbulbs, so he quickly learned to make each picture count.

“I knew the music, I knew the musicians, I knew in advance when the right moment would arrive,” he wrote decades later in his book of photographs, “The Golden Age of Jazz.” “It was purposeful shooting.”

He tried to capture not just a moment but the musicians’ inner qualities — the cool of Monk at the keyboard, wearing a goatee and a beret; the playful Gillespie peeking out from behind Fitzgerald at the mic; Ellington in his dressing room, as sophisticated as the music he created.

When he photographed Django Reinhardt, Gottlieb made sure to show the mutilated fingers of the guitarist’s fret hand — the result of a fire that left Reinhardt badly burned and forced him to learn to play his instrument again.

His photo of Holiday, lost in a mid-song moment, is perhaps the most famous image in jazz; decades, later, it served as the basis for a postage stamp. You could, Gottlieb wrote, look at the photo and feel the anguish in her voice.

Gottlieb’s columns and his book are full of stories of his encounters with musicians — revealing, heartbreaking, funny.

Armstrong carried copies of his diet in his jacket pocket and would hand one to folks he thought could use the help. Gottlieb once ran into him at a dentist’s office, and they stopped to chat. Armstrong started to leave, then turned back, looked Gottlieb up and down and pulled a sheet of paper from his pocket. “Hey, Pops,” Armstrong said. “There’s this diet, man. The greatest. Try it.”

This 1947 photo of Billie Holiday, is one of the most iconic images in jazz. Photo: William P. Gottlieb. Prints and Photographs Division.

By late 1948, drugs and alcohol had taken such a toll on Holiday that she frequently failed to show up for gigs. At one such show, Gottlieb, on a hunch, went to the dressing room and found her there, half dressed and totally out of it.

“I helped her get herself together and led her to the microphone,” he later wrote. “She looked terrible. Sounded worse. I put my notebook in my pocket, placed a lens cap on my camera and walked out, choosing to remember this remarkable creature as she once was.”

The hundreds of photos of the Gottleib collection allow us to do the same, to remember this remarkable American art form, as it once was.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 26, 2022

Pocket Globes: The Whole World in Your Hand

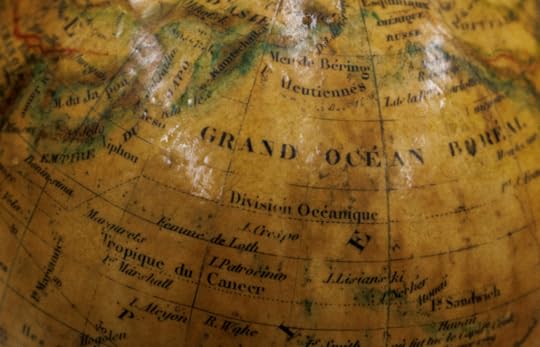

A pocket globe that turns on a spindle, housed in a protective box, from the collection of Jay I. Kislak. Photo: Shawn Miller. Geography and Map Division.

Pocket globes, the colorful, world-in-miniature creations of 17th- to 19th- century cartographers, were never a serious venture. Charming trinkets, 3-inch art objects for a gentleman’s desk. A child’s toy. A bygone artifact of the age of exploration.

“They were the kind of thing you’d keep on your desk next to the inkwell and blotting paper,” says John Hessler, curator of the Library’s Jay I. Kislak Collection.

He’s standing in a storage room of the G&M Division, a large, clean space with horizontal filing cabinets for maps and prints. Set out on top of one of these is a collection of 74 pocket globes, given this month to the Library by Kislak’s family and the foundation he left behind. It was, to the best of the Library’s knowledge, one of the largest private collections in the world. It’s now part of the national library.

The dozens of tiny globes, crafted between 1740 and 1875 in Europe and the U.S., are made of everything from ivory to papier-mache. The largest can fit in the palm of your hand. The smallest, in the center of your palm. There are some on stands and others in plush round boxes. Some feature a tiny globe covered in vellum, with continents and countries painted in delicate colors.

The exteriors of their encasing boxes are made of shark skin. Open other boxes and you’ll find the interior – curved, to accommodate the globe – painted with constellations, as if the night sky were a sphere of its own. Some turn on tiny spindles; others are fixed in place.

The lettering and artwork on the globes reveal the world as it was understood in earlier centuries. Photo: Shawn Miller. Geography and Map Division.

The donation brings the total number of pocket globes in the Library’s collections to nearly 100, an extraordinary size, as Kislak was a prodigious collector. His collection at the Library of Mesoamerican art, artifacts, rare books and manuscripts – more than 3,000 items in all – dates from around 2000 BCE to the 21st century.

The pocket globes are a British creation, believed to be first made by mathematician and printer Joseph Moxon in 1673, according to the Whipple Museum of the History of Science, part of the University of Cambridge in the U.K. While globes are believed to date back 2,000 years to the Greeks, the oldest surviving one (the Erdapfel, or “Earth Apple”) was made in Germany in 1491 or 1492. Famously, it did not include the Americas.

Moxon started making his miniature globes, about 3 inches in diameter, more than 150 years later, when the curvature of the Earth and its land masses were much better understood. The little globes reached their peak popularity in the late 18th century.

They were not serious scientific objects but artistic ones, with the continents and countries outlined in different colors, complete with place names, tiny paintings of fanciful animals or zodiac signs in the ones with constellations in their shells. Finer ones, made of ivory, were likely “status symbols for wealthy gentlemen,” the museum notes, a desktop ornamentation in a proper library that would have shown a taste for fine art in the sciences. Simpler models were toys for children, perhaps to show how the globe spun.

Today, anyone can buy a tiny globe, made of rubber or plastic, things that only cost a few cents to make, the geographic world a known entity. This collection of pocket globes is a reminder of an earlier time (not all that long ago) when the complete planet was something bold and original to consider; something that was a marvel to be able to hold in the palm of one’s hand.

Dozens of pocket globes from the private collection of Jay Kislak, recently donated to the Library. Photo: Shawn Miller. Geography and Map Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 24, 2022

Free to Use and Reuse: Athletes!

The cover of Fawcett Publication’s Jackie Robinson comic #5 from 1951. Serial and Government Publications Division.

This is a guest post by Amelia Torres, a spring intern in the Office of Communications.

The Library’s Free to Use and Reuse sets of copyright-free prints and photographs are, as always, yours for the taking. You can explore sets that include compilations of travel posters, autumn and halloween, weddings, movie palaces and dozens more.

Since summer sports are upon us, let’s check out this one on … athletes!

Jack Roosevelt Robinson — Jackie — is one of the most consequential athletes in national history, and arguably the most.

In 1947, when brutal Jim Crow segregation still ruled most of American life, Robinson broke the color line in professional baseball, at the time the nation’s preeminent sport. Playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers, mostly at second base, he endured innumerable death threats to become Major League Baseball’s Rookie of the Year, later its Most Valuable Player and a first-ballot Hall of Famer.

He went on to a second career as a prominent activist for civil rights and social justice, setting the template for the athlete-activist that continues today. His daughter, Sharon, was at the National Book Festival in 2019, discussing her memoir on growing up with her father and his commitment to social justice, “Child of the Dream.”

Today, Major League Baseball has not only retired Robinson’s jersey number, 42, from the entire league, but on April 15 — the anniversary of Robinson’s debut — every player on every team wears his number. No player in any other sport is honored in this way.

Even when he was still playing, though, Robinson seemed larger than life: He got the comic-book treatment as a hero then, too.

The photo above is the cover of Fawcett’s #5 in its “Jackie Robinson” series, which ran for six original issues over four years. (The Library has four of these.) This one from 1951 is 36 pages and includes biographical stories about Robinson, from a narrative of a series against the St. Louis Cardinals to his college days at UCLA.

The cover features Robinson wearing his blue Dodgers cap, his name in raincoat yellow, the rest of the type in bright white with lots of exclamation points. All of this was set against a bright orange background, the type of eye-popping color scheme typical of Fawcett comics.

Comic books in the midcentury covered all sorts of things, from romance to superheroes, but it’s important to keep in mind that Robinson’s comic was before segregation was overturned. It was more than a decade before the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965 transformed much of American life. Before all this, Robinson was inspiring the nation — even its young readers — to believe in a future that they couldn’t yet imagine.

All for just 10 cents.

Joan Newton Cuneo behind the (sizable) wheel in the 1910s. Photo: Harris & Ewing. Prints and Photographs Division.

Joan Newton Cuneo, people! Race driving queen!

The lady was born into a wealthy family in Holyoke, Massachusetts, in 1876. As a kid, she learned how to operate one of the family’s steam trains. She took to newfangled automobiles, too.

By 1905, she was 29, a wife, mother, and race car driver, initiating a trailblazing career that lasted a decade. She hit the Glidden Tour for several years, road rallies that went several hundred grueling miles across parts of the country; roads, having never been made for automobiles, were terrible. She crashed. She came back. She had great success at a series of races in New Orleans. In every race, she held her own against male competitors. She once hit 111.5 mph on the Long Island Motor Parkway, a record for female drivers. She was a national celebrity.

Racing officials never warmed to the idea of a woman behind the wheel, though, and women were soon banned from races in the American Automobile Association. She kept on for a while, but a divorce, more bans against women drivers and a remarriage to a wealthy mill owner led to a more traditional life in Ontonagon, Michigan, a small village on the shore of Lake Superior.

She died in 1934 at the age of 57, her fame and exploits mostly forgotten.

“Mad for Speed: The Racing Life of Joan Newton Cuneo,” a 2013 biography by Elsa A. Nystrom, revisited her extraordinary career. In June 2018, the National Automobile Museum put her on the cover of its magazine, Precious Metal, describing her as a “racing hero.”

Above, we catch up with her in her prime, sometime between 1910 and 1917. Oddly, she posed without one of her signature hats. Nystrom writes that Cuneo always appeared in public as “feminine, not a feminist, dressed as a lady should … (but) not afraid to challenge the male establishment.”

You can see that sensibility here, in the common-sense bun, the wedding ring and a driving uniform with what appears to be a pleated skirt. It’s a picture that says power, direction and drive.

Women in a low-hurdle race in Washington, D.C., in the 1920s. Photo: National Photo Company. Prints and Photographs Division.

Lastly, let’s check out a track event, the low hurdles. This was particularly challenging for women in the early years of the 20th century, as proper ladies were deemed to be too delicate for most forms of strenuous exercise, much less competitive athletics, so our hurdlers had to make do with bloomers, skirts and blouses.

Women were allowed in a few events in the second modern Olympics in 1900, but of the 997 athletes in those games, only 22 were women. There were no Olympic track events for women until 1928. (Today, all Olympic events have female competitions and 48 percent of all Olympic athletes are women.)

The photograph above was taken in the 1920s at Central High School (now Cardozo) in Washington, D.C. The clothing certainly suggests we’re not fully in the Jazz Age, so it’s likely this was early in the decade.

Our hurdlers don’t appear to be teenagers, they’re not wearing school colors and there are no students in the stands, so we’re guessing this was not a school function but some festive holiday event — perhaps the Fourth of July, Memorial Day or Labor Day weekend. The sailors in uniform and the large American flag at the bottom left give that idea some support.

Some lively music, lemonade, a civic speech or two and some light-hearted athletic competition; look, the ladies are running the hurdles! The sun is out, there’s a light breeze, it’s a good time. World War I and the flu pandemic are over now; the Roaring Twenties are upon us.

Title IX, the landmark legislation that would pave the way for equality in women’s sports, was still half a century away.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 19, 2022

War as They Saw It

A Soviet tank rusts in the Afghan countryside. Photo: Dean Baratta. Veterans History Project.

— This is a guest post by Nathan Cross, an archivist in the American Folklife Center. It first appeared in the Library of Congress Magazine.

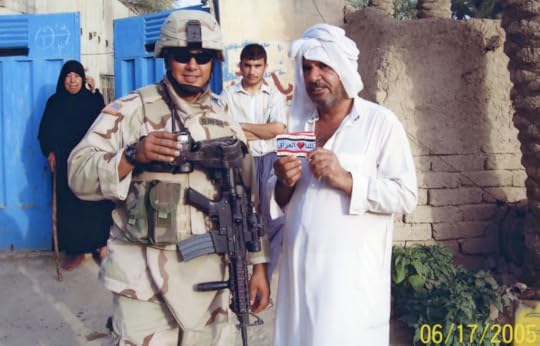

Service members long have used photography as a means of capturing the essence of their experiences. As technology improved, cameras became more available, and pocket-sized digital cameras gave service members in Iraq and Afghanistan the freedom to take hundreds of photographs without having to worry about running out of film.

Today, hundreds of those images are housed in the collections of the Library’s Veterans History Project. The project recently released a research guide focused on photo collections contributed by veterans of the global war on terror that followed the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

Joseph Beimfohr’s photos let viewers peek into his war.

Beimfohr enjoyed his time in the Army, as can be seen by his broad smile in photos with Iraqi soldiers and civilians. But he did not shy away from harsh realities, either, and he prepared himself and his soldiers for the worst situations they could face. In his photos, he and his section undergo medical training, learning to start IVs — an unpleasant but necessary skill when lives hang in the balance.

Joseph Beimfohr in Iraqi in 2005 in full battle gear. Photo courtesy of Joseph Biemfohr. Veterans History Project.

On July 5, 2005, Beimfohr faced one such worst-case scenario. An improvised explosive device detonated under his feet, grievously wounding him and killing another soldier. Injured in both legs, his hand and abdomen, Beimfohr had both legs amputated. Despite being told by doctors he wouldn’t walk again, Beimfohr was walking on prosthetic legs within six weeks and went on to compete in adaptive sports such as paramarathons and paratriathlons.

“I’ve learned that we place the limitations on ourselves as far as what we think we can’t do,” he said. “People will tell guys that are injured, ‘Oh, you won’t be able to walk, you won’t be able to do this and you can’t do that.’ And then we go out and do it.”

Beimfohr gutting it out in rehab. Veterans History Project.

Dean Baratta served as an Army intelligence specialist deployed to Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan as part of a task force responsible for base security.

In an early email home, Baratta characterized his unit’s mission in optimistic terms: “So many armies have come to Afghanistan to fight and die for prestige, money or power. We actually have the opportunity to make the lives of countless people better and, in turn, the world safer for everyone.”

The photos in his VHP collection convey a palpable sense of dashed hope, of shattered idealism. There are joyous scenes, such as a Christmas parade at Bagram, and idyllic vistas of the Afghan mountains and countryside are captured in rich colors. But there also are heart-wrenching pictures of poverty and the detritus of decades of war — often in stark black and white.

In his day-to-day work analyzing security threats around Bagram, Baratta learned firsthand the frustrations of trying to bring about positive change as part of an unwieldy international intervention while navigating complex and often cynical local politics.

“I’m an idealist at heart, and I went in really hoping to see some change and being able to point to one thing that I really improved some lives or made things a lot better or something,” Baratta said in his VHP oral history. “And I left not really feeling that way.”

The photos of other Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in VHP’s holdings provide many other visual accounts of service and sacrifice. Captured in the oral history interviews they gave and the personal photographs they took, these veterans’ stories offer a human collage of the American military experience in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free.

May 16, 2022

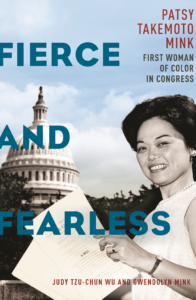

Researcher Story: U.S. Rep. Patsy Takemoto Mink, First Woman of Color in Congress

Congressional portrait of U.S. Rep. Patsy Takemoto Mink, 1994. Prints and Photographs Division.

Judy Tzu-Chun Wu and Gwendolyn Mink co-wrote “Fierce and Fearless: Patsy Takemoto Mink, First Woman of Color in Congress,” published this month. Wu is a professor of Asian American studies at the University of California, Irvine. Mink is a scholar and writer, who with her father donated her mother’s papers to the Library in 2007. Their biography is the first to delve into the life of the trailblazing legislator and champion of Title IX.

How did the two of you decide to collaborate?

Wu: When I started conducting research on Patsy Mink, Wendy Mink was one of the first people I contacted. We began with conversations and oral history interviews, then we decided to become co-authors. Wendy lives near the Library, so I would visit her and have dinner at least a couple of times a week while I was in D.C. for research.

Patsy wanted Wendy to write her biography, but I believe Wendy felt uncertain as to how to move ahead. As a political scientist, she did not want to write a completely personal biography of her mother. And as the daughter of Patsy Mink, Wendy did not want to write like a political scientist about someone she knew so intimately.

I’m so grateful for this collaboration, because Wendy authored beautiful and moving memoir vignettes that begin each chapter. She also read and edited all the chapters for accuracy and to add some details. I think it’s fitting that we have this feminist partnership to collectively write about someone who practiced feminist political collaboration.

Mink: Meeting Judy was a godsend, our decision to collaborate resolving my own inner drama over how to write as one person with two voices, the personal and the political-historical, simultaneously memoir-ish and scholarly. Writing was sometimes painful, especially when excavating certain experiences, but working with Judy was always a joy, and our common project was always motivating.

Tell us about Patsy Mink and why she’s important.

Judy Wu. Photo courtesy of the author.

Wu: Patsy Mink is largely overlooked in academic studies and popular memories of feminist politics of the 1960s onward. The recent Hulu miniseries, “Mrs. America,” exemplifies this historical amnesia. Mink was not even a character on the show, even though she was a key feminist, antiwar and environmentalist legislator and political leader during the so-called second and third wave of feminism.

Mink advocated for intersectional feminist policies that carefully considered how race, class and gender shaped women’s lives. As a third-generation Japanese American from Hawaii, she brought a Pacific worldview with her to Washington, D.C. And, she worked collaboratively with those outside of the halls of Congress, particularly movement activists, to develop and advocate for policies to achieve equity. Given how jaded most Americans are about politicians, I believe Mink served as a model for ethical political leadership.

What resources did you use?

Wu: I became inspired to research Patsy Mink because I saw a feature on the Library website about her papers. As a historian, I relish the exploration of archives. However, I don’t think I understood how much archival materials the Library holds (over 2,000 boxes). I began researching Mink in 2012, and the book is coming out 10 years later. That’s how long it took to go through the materials, and I wasn’t even able to read everything or write about everything that I read. I also researched other collections, but the Library’s constituted the central source.

Mink: I began exploring my mother’s papers episodically in 2007–08. I started at the beginning of the collection and worked my way through chronologically, collecting scans of materials I expected to consult later when I was ready to put a story together.

I began to work in the papers systematically around 2010 or 2011 and was prepared to begin writing about the early period but was stymied by inner debates over voice. Even with writer’s block, I continued to collect and organize scanned materials from the collection.

Once Judy and I decided to collaborate and the idea of vignettes emerged, I began to chart my explorations in the collection based on topics I needed to cover. The finding aid worked miracles in helping me reach across the collection to find materials in varied locations about common subjects.

Did your research lead you to any surprises?

Wendy Mink. Photo courtesy of the author.

Mink: Given my close relationship to the subject, I can’t really say that I was surprised by my encounters with the collection. But I was delighted to be reminded that my mother kept everything. So, there’s lots of context material, third-party material, movement/activist material in the collection that help to flesh out decisions she made, projects she was part of, struggles she engaged.

Wu: There were many surprises for me. One of the periods of Mink’s life that I find fascinating is her time away from the House of Representatives. She served both on the Honolulu city council and in the State Department as assistant secretary of oceans and international environmental and scientific affairs. It was so interesting to see how consistent Mink’s political values were, whether she was in the halls of Congress or in the city council.

Also, Mink’s time in the State Department revealed profound differences between the executive versus the legislative branches of government. On the one hand, Mink had greater reach as an assistant secretary. On the other hand, she was so hamstrung by the bureaucracy, particularly one that privileged male knowledge and expertise and organizational hierarchies. Although Mink also faced obstacles as a legislator, she definitely thrived and preferred the role of being a lawmaker.

What advice do you have for other researchers using the Library’s collections?

Wu: I benefited so much from being able to talk to Meg McAleer, the historian in the Manuscript Division who processed Mink’s papers. Her insights about the collection and how Mink’s presence in the paper archives differed from other congressional papers were really helpful. So, if you have a chance, talk to the person who processed the collection!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 11, 2022

Letters Straight to Your Heart: The Library’s Centuries of Correspondence

Jacqueline Kennedy at the memorial service for Robert Kennedy. She wrote conductor Leonard Bernstein afterwards, in a letter now at the Library. Photo: . Prints and Photographs Division.

This article also appears in the Library of Congress Magazine.

The letter, written on vellum, is more than 500 years old. It is one of the most consequential missives in world history. It is one of the top treasures of the Library, sealed away in a secure cocoon.

Written in the wake of Christopher Columbus’ 1492 voyage to the west, the letter from Pope Alexander VI to the Spanish monarchy gives them papal authority to forever claim “all islands and lands, discovered and to be discovered, toward the west and south, that were not under the actual temporal rule of any Christian powers.”

Many scholars believe it is the first written reference to the New World, and it lays out the deadly course of colonialism that Europeans were to inflict on the peoples of the Americas.

The Library’s scribal copy of the letter, a papal bull known by its Latin name of Dudum siquidem, is from around 1502. It is one of three copies known to still exist.

As world-changing as it was, it’s only one letter in the Library’s stunning collection of correspondence that has helped shape the world as we know it, stretching back more than a thousand years. Written by the famous and the forgotten in any number of languages and dialects from all over the world; penned, etched, scrawled, typed and penciled in by kings, presidents, scholars, soldiers, nurses, artists, trade workers, escapees from slavery, musicians, baseball players and beauticians; about subjects from the weighty to the whimsical; the letters can be found on everything from ancient vellum (as calfskin is called) to dime store postcards.

Let’s look at a couple of thank you notes, those timeless missives of good manners, to get an idea of the range we’re describing.

Here’s one in Latin that Ivo, the bishop of Chartres in France, wrote to Matilda of Scotland, queen consort of Henry I, around 1100 A.D., thanking her for help in repairing his church’s roof. And here’s one from Fred MacMurray, cast as the antihero in 1944’s “Double Indemnity,” to James M. Cain, author of the original book, thanking him for saying kind words about his performance.

Dates and documents record the bare bones of history, of what happened when and where. Personal letters tell what it felt like at the time, capturing the humanity of the age. Intimate, rarely written for publication, they are poignant reminders that while epochs and eras change, the affairs of the heart do not.

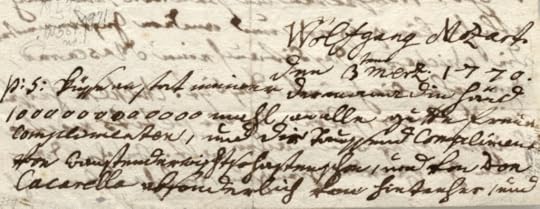

“Wolfgang Mozart.” The young musician signed this letter in 1770. Music Division.

“Kiss mamma’s hand for me 1000000000 times,” wrote Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, a sunny 14-year-old, on March 30, 1770, to his sister, Marie. He was performing in Italy. Like most kids, musical prodigies or no, who are way from home, he was missing his mom.

“It’s 4:00 in the morning — after this long day,” Jacqueline Kennedy wrote to Leonard Bernstein on June 8, 1968, sleepless after the funeral of her brother-in-law, Robert F. Kennedy, who had been assassinated. Bernstein, a close friend, had conducted the music at the service.

Now, as the nation reeled in the long hours of the night, she was huddled alone at a desk in her mother’s Georgetown home, no doubt haunted by the earlier assassination of her husband, President John F. Kennedy. “Everyone has gone to bed — but I just want to stay up by myself — to think about so many things — and about today — In awful times — I think the only thing that comforts you is the goodness in people —”

Love, one is reminded in this cascade of letters, takes many different forms in many different eras. John Carvel Arnold, a Union soldier in the Civil War, was stationed near Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, on Aug. 28, 1864, pining for his wife, Mary Ann, back home in Pennsylvania.

“I want you to write to me oftener than you do,” he wrote, even though she was illiterate.

“Dear and Beloved Husband,” she had a friend write back two months later, showing a trace of marital affection and irritation, “you no (sic) that i can’t write myself and so i can’t write back when i pleas (sic).”

The Library, the largest in world history, has hundreds of thousands — if not millions — of these moments, frozen in time.

Here is Ralph Waldo Emerson, the great American poet and philosopher of his day, writing to an obscure newspaper reporter named Walt Whitman on July 21, 1855. Emerson was extolling Whitman’s self-published book of poetry that almost no one had read. It was called “Leaves of Grass.”

“I greet you at the beginning of a great career,” Emerson famously wrote, his letter launching Whitman to fame, saying that his “free brave thought” had resulted in “incomparable things said incomparably well.”

The collections are also filled with other voices, singing not of America’s glorious raptures, but railing against discrimination, violence and oppression, the fiery American determination that insists on the freedoms promised in the Constitution.

“I will never consent to have our sex considered in an inferiour (sic) point of light,” wrote Abigail Adams, the second first lady of the United States on July 19, 1799, to her sister.

Elizabeth Blackwell, the nation’s first female physician, on March 4, 1851, wrote a spirited rebuke to her friend Lady Noel Byron, who had suggested that women physicians should take a “second place” to men.

“I do not wish to give (women) a first place, still less a second one — but the most complete freedom, to take their true place whatever it may be.”

“Parks, my dear husband…” Rosa Parks wrote to her husband on October, 11, 1957. Manuscript Division.

In January of 1966, during the heyday of the civil rights movement, jazz singer and activist Nina Simone (famed for her iconic “Mississippi Goddam”) urged her friend and fellow jazz artist Hazel Scott, who had been living in Paris, to come back home: “…everybody is in fight now, Hazel — everybody — And it’s exciting!!!”

There are also moments when one can see great names of history caught up in frustrations known to us all. Who, in an era when email and texting has replaced much of traditional letter writing, hasn’t written out an angry email — and then, upon mature reflection, hit the delete button?

Abraham Lincoln knew your pain.

On July 14, 1863, he wrote a three-page letter to the nation’s chief military leader, Gen. George Meade, chastising him for not pursuing the defeated Confederate Army after Gettysburg. And then, thinking the better of it, stuffed it in an envelope, writing on the outside: “To Gen. Meade, never sent or signed.”

And finally, there are glimpses of moments that make the nation what it is.

Woody Guthrie in 1943. Photo: Al Aumuller. Prints and Photographs Division.

Woody Guthrie, one of the most influential singers of the 20th century, was always moved by the idea that the nation belonged to the millions of its unknowns, the sorts of hardworking men and women that Whitman and Zora Neale Hurston and so many others had written about. He wrote the first draft of “This Land Is Your Land” in 1940 to emphasize the point, with lyrics that would be finalized as:

This land is your land, this land is my land

From California to the New York Island

From the Redwood Forest to the Gulf Stream waters

This land was made for you and me

A few months later, on Sept. 19, he wrote to Alan Lomax, his friend who, along with his father, John, headed the Library’s Archive of American Folk Song (now part of the American Folklife Center). Guthrie’s letter hums with his twangy Oklahoma accent, his wisdom of the prairies, the ribbon of highway peeling away into the distance, the song of the nation at the tip of his pen:

“All I know how to do Alan is to keep a plowing right on down the avenue watching what I can see and listening to what I can hear and trying to learn about everybody I meet every day and try to make one part of the country feel like they know the other part and one end of it help the other end.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers