Library of Congress's Blog, page 28

November 1, 2022

Indigenous Cultures at the Library: Kislak Family Foundation Gives $10 Million for New Gallery

An artist’s sketh of part of the new Kislak exhibition.

The Kislak Family Foundation is donating $10 million to create a new exhibition at the Library that will share a fuller history of the early Americas, featuring the Jay I. Kislak Collection of artifacts, paintings, maps, rare books and documents, the Library announced today. The new Kislak Gallery will be part of a reimagined visitor experience at the national library in the years ahead.

The gift will both develop the exhibition gallery and establish a permanent endowment for its maintence and renewal over time. The announcement of this major gift was announced on the 125th birthday of the Library’s historic Thomas Jefferson Building.

“The Kislak Family Foundation continues to be such a special partner to the Library of Congress in telling the magnificent story of our world,” said Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden. “With this generous gift, we are honored to continue Jay Kislak’s legacy through this newly renovated gallery that thoughtfully shares with visitors the rich and complex histories of those who came before us.”

“Voices of the Early Americas: The Jay I. Kislak Collection” is slated to open in 2024. The exhibition will explore both the history of the Native cultures of the Americas before and after European colonization. Curators aim to show how complicated this story is, how Native American cultures were violently conquered, sometimes enslaved, and how vibrant they are today. This deep past continues to inspire many people, including modern artists, writers and poets, whose works will also be featured.

“My father wanted this collection to live on well beyond his own time at the finest institution in the world,” said Paula Kislak, chair of the Kislak Family Foundation. “By reimagining how this unparalleled resource informs and inspires the American people, the Library of Congress will ensure that his vision comes to fruition for future generations. We are pleased to make this gift to the Library of Congress.”

In 2004, Kislak first donated nearly 4,000 items from his collection to the Library. Select pieces from the collection were featured in a previous exhibition. These included rare masterpieces of Indigenous art, maps, manuscripts and cultural treasures documenting more than a dozen Native cultures and the earliest history of the Americas.

The new exhibition will provide a fuller narrative and chronology to tell the story in an immersive and informative new gallery. It will display more items from the Kislak collection as well, with some artifacts dating back some 3,000 years. Many objects will be displayed for the first time through a state-of-the-art, transparent artifact wall. The exhibition also will incorporate select items from other Library collections, mixing in textiles, rare books, manuscripts, photography, and other artistic works. These will put the Kislak collection in context and provide visitors with a comprehensive view of the profound impact of these early civilizations.

An artist’s sketch of the Kislak exhition.

“‘Voices of the Early Americas’ will give voice to the pre-Columbian cultures of the Americas,” said John Hessler, the exhibition curator. “It is my hope that our visitors will have a different idea of the history of the early Americas after they explore this gallery. A central theme will examine how the Americas we know today grew out of a polyphony of voices – a mixing of Indigenous, African and European cultures.”

An external advisory committee of scholars and curators will help shape the exhibition’s development. Ralph Appelbaum Associates is designing the exhibition.

The Library is committed to observing legal and ethical standards in acquiring and displaying cultural artifacts. Kislak acquired many of the pieces between 1981 and 2003. He donated his collection to the Library in 2004 so that the public might better appreciate the history and cultures of the civilizations in the ancient and early Americas.

Each object that will be on display has a significant story to communicate to current and future generations about the craftspeople, painters, potters and metalworkers who produced them.

The gallery is part of the Library’s plan to build “A Library for You,” transforming the experience of its nearly 2 million annual visitors, sharing more of its treasures with the public and showing how Library collections connect with visitors’ own creativity and research.

The Kislak gift will build on the significant investments of Congress and private philanthropy in the Library’s infrastructure, exhibitions and programs, all delivering on the Library’s commitment to open its doors wider to all people everywhere. In 2020, philanthropist David Rubenstein announced a lead gift of $10 million to support the visitor experience plan. Congress has appropriated $40 million as part of this public-private partnership.

October 26, 2022

Ida B. Wells, W.E.B. Du Bois, and the Maps of American Racism

Ida B. Wells, the investigative journalist and activist from Mississippi. Illustration from “The Afro-American Press and Its Editors,” 1891. Prints and Photographs Division.

Ida B. Wells was 30 years old in 1892, living in Memphis and working as a newspaper editor, when a mob lynched one of her friends.

Distraught, the pioneering journalist set out to document the stories of lynching victims and disprove a commonly asserted justification — that the murders were a response to rape. Wells’ own friend was killed after a dispute over a marble game.

Wells is renowned for her fiery writing and for her precise reporting that now is recognized as trailblazing: She won a posthumous Pulitzer Prize in 2020 for destroying the myth about rape and lynching and for her reporting generally on racist violence. She is not known, however, for her contributions to demographics.

Yet, she compiled extensive place-based statistics on lynching deaths, mostly from newspaper reports. This summer, two interns injunior fellows progmam in the Geography and Map Division mined Wells’ numbers using geospatial tools and combined them in a StoryMap with historical cartography, 20th-century redlining maps and census data to offer insights of racial injustice, from the legally systemic to incidents of violent terrorism.

“Often, maps reflect our history in deep and profound ways, allowing us to grasp what they have to communicate immediately, as if we are looking into a mirror and seeing ourselves,” said John Hessler of G&M, who directed the work.

The project was inspired by a discussion Hessler had last year with Rep. Jim Himes of Connecticut, chair of the House Select Committee on Economic Disparity and Fairness in Growth. For a committee report, Himes asked Hessler how the Library’s GIS (geographic information system) data visualization capabilities might make the committee’s findings come alive for readers.

Himes also wanted to bring to light “some of the missing history of how we got to where we are today and how inequality developed, especially in the post-Civil War period,” Hessler said.

Himes’ inquiry led Hessler to search through historical maps he knew were relevant and to discover additional sources.

One of W.E.B. Du Bois’ maps of Georgia, circa 1900.

The civil rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois is perhaps the most well-known Black intellectual and activist to use cartography to bring attention to racial disparities. Du Bois also mapped African American land ownership and wealth in the late 19th century.

The Library has held a selection of Wells’ and Du Bois’ work for many years, but the resources are not heavily used. Likewise for related but more ephemeral maps in the collections, including those published in The Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP, of which both Wells and Du Bois were founders.

“Much of this material is completely unknown,” Hessler said.

He concluded it warranted a deep dive, and he organized a junior fellows project as an initial step. The result is “The Mapping of Race in America: Visualizing the Legacy of Slavery and Redlining, 1860 to the Present,” a StoryMap by junior fellows Catherine Discenza and Anika Fenn Gilman.

It pulls together Wells’ lynching statistics, Du Bois’ maps and much more — the project expanded as the fellows discovered new resources and information.

The list of lynchings in Wells’ “A Red Record” was used to create this map, showing how widespread the killings were.

Some historical maps appear as they were published, but Discenza and Gilman also used GIS to create their own visualizations from data. All the data in the StoryMap is downloadable, and links take researchers to sources used. About 75% of the content originates from Library collections — population and census data from the nation’s earliest years, images from digitized statistical atlases, county-by-county maps of the enslaved population.

Also included are redlining maps from the 1930s to ’60s from the University of Virginia’s Richmond Center. Redlining maps “are something that came up right away” in discussions with Himes and his committee, Hessler said.

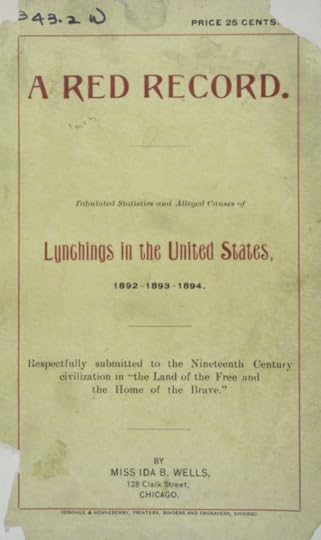

Cover of “A Red Record,” Ida B. Wells groundbreaking research into lynching. Image: New York Public Library

Unlike Wells’ data tracking racial injustice and Du Bois’ maps visualizing African Americans’ economic contributions, redlining maps served an entirely different purpose. Banks used them to deny loans to homeowners and would-be homeowners in neighborhoods deemed undesirable, leading to neighborhood decline. Red shading marked these neighborhoods, in which people of color had been forced to live, hence the maps’ name.

Combining redlining maps with the other data from the project highlights important questions: What does the history of mapping of race look like in the United States? Who was doing it? Who was using it? What were they using it for?

The redlining maps in the StoryMap focus on three cities: Baltimore; Tampa, Florida; and New Orleans. Baltimore served as an initial case study. Hessler and the fellows combined redlining data from the city with more recent spatial data, including modern median income, health insurance coverage and housing occupancy.

“The correlations between redlining and economic development and growth was very clear in Baltimore,” Hessler said.

Next, he invited Discenza and Gilman to each elect a city. A senior at the University of Florida, Discenza majors in medical geography and minors in health disparities. Originally from Tampa, she chose that city.

Gilman is a senior at Tulane University double majoring in mathematics and international relations, and she has a certificate in GIS. She selected New Orleans, home to Tulane.

Both found inspiration in the project. “I’m really happy to be getting this specific experience. It’s the sort of thing that I’m genuinely interested in pursuing,” Discenza said.

“Seeing how what I’m interested in can play out in a public arena definitely gives me a lot of ideas about how I can use the skills I’m developing now,” said Gilman, who plans a career in geopolitical analysis.

The StoryMap builds on a growing body of research and documentation about the nation’s history of white supremacist violence and policies that have created the physical landscape we live in today.

Historian Richard Rothstein, for example, wrote about redlining in the bestselling 2017 book “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America,” showing that boundaries of urban slums were often created by white-run governments, monetized by banks, legalized by courts and enforced by police. The history of lynching is also well documented, and in 2018 the Equal Justice Initiative opened the nation’s first memorial documenting the nation’s centuries of violence targeting Black Americans: the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

The project points to how other complex issues might be examined, too — one need only look at its treatment of Wells’ data to understand the power of the approach.

“GIS and a StoryMap application can bring this data back and show that these were real people, not just old lifeless statistics.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free.

October 24, 2022

Leslie Jordan: Farewell, and We Are Not Doing Okay.

The late Leslie Jordan. Photo credit: Sean Black.

Leslie Jordan died of an apparent medical emergency this morning while driving in Los Angeles. His beloved BMW crashed into the wall of a building. He was pronounced dead at the scene. No one else was hurt. He was 67.

Adorable, generous and hilarious to the very end, one of his last public appearances was at the National Book Festival in September. He was on the main stage to talk about his latest book, “How Y’all Doing? Misadventures and Mischief from a Life Well-Lived” with Megan Mullally, his Will & Grace co-star. Well, technically he was promoting the book. Actually, he was just cutting up, at which he was very accomplished, as television, film and Instagram devotees well know.

Here’s their conversation:

I interviewed him via Zoom a few weeks before the festival and again on camera that day. (“Interview” is a loose term; one just lobbed him softball questions and let him swat them out of the park.) We both grew up in very conservative Southern Baptist households, one state over and about half a generation apart, and both moved on to different lives. As soon as I clicked into the video call, he said, “We’re just gonna’ have at it.”

We did, and that was his magic: He made everyone feel they not only knew him, but that they had always known him. His humor and public persona were based on his unique identity: very Southern, very openly gay and very short. (He stood 4’11” and proudly referred to himself as a “Southern Baptist sissy.” He pronounced his hometown of Chattanooga, Tennessee. as “Chattanugga.”) He was never conflicted about his sexuality, he often said, and his literary heroes as a young man were Truman Capote and Tennessee Williams, two Southern writers who were among the most flamboyant gay men of their generation. That took a lot of guts for those men, and I don’t think their bravery was lost on him.

“Truman Capote and Tennessee Williams saved my life,” was one of his go-to quotes on this book tour.

He was exactly like you think he would be, too: a complete lack of pretension, good natured, ready to laugh and ready to make you laugh. Surprise of the conversation? He said that he was once cast as Capote in a play — which would seem like perfect casting — but had to withdraw just before opening night. He couldn’t get past Capote the public character and the find the man himself. And, he candidly said, the part required him to memorize large chunks of monologues, which he just couldn’t nail down.

Here’s a clip that was perfectly him. It’s from near the end of our conversation, after I asked when he knew for certain that he was gay. Like a true Southerner, he did not respond with an answer; he answered with a story:

That wit is the sort of talent that propelled him to rack up more than 130 television and film credits in a 36-year career. Most famously, he starred in “Will & Grace,” for which he won an Emmy. He also popped in several seasons of “American Horror Story,” had a supporting role in “The Help,” The United States vs. Billie Holiday” and “Sordid Lives.” He was starring in “Call Me Kat,” opposite Mayim Bialik at the time of his death.

It was not easy for him to succeed in public life during his generation with his over-the-top manner, of course. Overcoming the religious and social strictures of his youth and the larger social mores of the 1970s and 1980s took its toll in drugs and alcohol abuse, the same demons that had tormented Capote and Williams. But he found a way past it. He went sober at the age of 42 in 1997, he said, after a stint in L.A. county jail. An earlier book, “My Trip Down the Pink Carpet,” was “full of angst,” he said in our conversation, something that he was “done with.”

That was one reason why his late-in-life success was so charming — because it was so clearly earned. He had won this peace, this self-acceptance, this good humor. He became a hero of the COVID-19 quarantine (when he was in his mid 60s) by filming short comic bits and filing them to Instagram. One after another went viral, to the point he amassed some 5.8 million followers, and a whole new generation found him as he was.

“It’s very young and it’s all female,” he said of his audience, when I asked. “I don’t have a single man following me … It’s young girls and they just adore me.”

Most everyone else did, too.

So, today, to answer his frequent conversation-starting question — “How y’all doing?” — today we have to answer, with a long sigh and a lowered gaze, “Not so good, partner. Not so good.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

October 20, 2022

A Fond Farewell to John Hessler, LOC Polymath

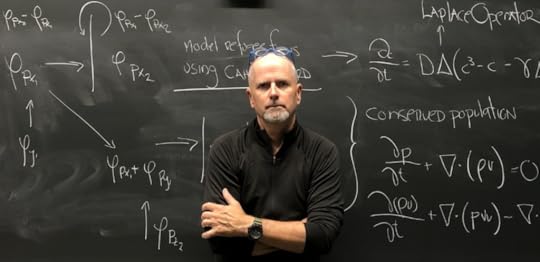

John Hessler. Photo: Courtesy of John Hessler.

Every institution has its institutions, and one of the Library’s is John Hessler, who will retire from the Geography and Map Division at the end of this month. He holds many titles, official and unofficial. One of the official ones is curator of the Jay I. Kislak Collection of the Archaeology & History of the Early Americas; one of the unofficial ones, playfully given to him by Librarian Carla Hayden, is the “Indiana Jones of the Library of Congress.” We will miss his erudition, energy and endless curiousity.

Tell us about your background.

I grew up in New York City and spent most of my youth wandering around the American Museum of Natural History.

When I was 9 years old, one of the geology curators who noticed I was there all the time invited me behind the scenes. Later, he took me on field trips and to the Rutgers Geology Museum, where I was the youngest member of the museum’s volunteer fossil preparers. It was there that I really learned about science and fieldwork.

While attending Villanova University as an undergrad, I became an avid mountain climber; I have always been drawn to remote and wild places. My graduate work and writing on Indigenous ethnobotany and linguistics in the Amazon reflects my love of fieldwork. Even now, I am studying the ethnobotany of the Cahuilla people in the deserts of Joshua Tree National Park.

What brought you to the Library?

I came to the Library after working for many years at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, where I was part of the entomology and botany departments.

My work there was in support of field biologists — mapping species distributions for biodiversity studies. My own research centered on mapping the biogeography of high-altitude Lepidoptera in the Alps.

I was paid not as a museum employee but out of research grants. So, at 40 years old, I thought I should finally get a real job, and I came to the Library in 2002. I’m a specialist in geographic information science in G&M.

You’ve contributed to diverse projects at the Library. How did your career evolve?

I have had a great deal of support and freedom to explore at the Library. Over the course of my time here, I have somehow managed to write 12 books, including the New York Times bestseller, “Map: Exploring the World,” which combines my thoughts on the modern and historical parts of the field.

I have also written books and edited facsimile editions about some of the Library’s great masterpieces like Galileo’s “Sidereus Nuncius,” Columbus’ “Book of Privileges,” Henry David Thoreau’s maps and, of course, the famous 1507 world map by Martin Waldseemüller.

What achievements are you most proud of?

The thing I am most proud of is what I have been able to do with the Jay I. Kislak Collection. When I was asked to become its curator a little more than a decade ago, I was just finishing a stint as a Kluge staff fellow. Since that time, I feel that we have really put this collection on the map (no pun intended).

I was able to present classes on Mesoamerican archaeology and language, train my own docents, give lots of gallery talks, mentor 17 archaeological research fellows and sponsor scholarly conferences. Now, we are designing a new gallery that will open in early 2024.

Besides this, I was able to write a book about the collection called “Collecting for a New World: Treasures of the Early Americas.” For the first time, it tells the story of the collection’s amazing objects, books and manuscripts. This fall, my second book about the collection, “Exposing the Maya: Early Archaeological Photography in the Americas,” will publish. I dedicated it to Kislak’s memory.

What are some standout moments from your time at the Library?

Perhaps the two things that stand out the most are the acquisition of the Codex Quetzalecatzin and the recent purchase of the San Salvador Codex, yet to be digitized.

For someone who is interested in the Indigenous languages of the Americas, the ability to bring these spectacular objects into the Library collections is the standout moment. Never in my wildest dreams did I think it would be possible to bring two manuscripts of this rarity into our collections.

They are truly amazing pieces of Indigenous history, written in Spanish, Nahuatl and Mixtec hieroglyphs. The purchase of these manuscripts was, of course, not exclusively by me. G&M’s acquisitions specialist, Robert Morris, with whom I have worked with on numerous additions to the collections, first brought both of them to my attention. We worked closely with Library management to acquire these priceless objects.

What’s next for you?

In the coming months, I will be relocating to Nice, on the French Riviera, and I will also continue my teaching at Johns Hopkins University, where I have been on the faculty for more than a decade. I will also continue my teaching in the summer at Sorbonne Université in Paris.

Besides that, I have lots of travel in the coming months and will carry on with my writing for Alpinist Magazine, where I have been a frequent contributor for many years.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

October 18, 2022

“The Big Bang” of Cinema: Library Researcher Finds First Copyrighted Film

Some of the images from the first film to be copyrighted.

The perfectly folded letter opened, and pictures dropped out — 18 small images imprinted in two strips on a single sheet. Three men stand around an anvil, enacting a scene from a blacksmith’s shop, hammering and then drinking.

“I froze,” says Claudy Op den Kamp, the film scholar who extracted the letter from a Library archival box this summer. “I couldn’t grasp what I was holding.” She certainly hadn’t expected the pictures.

Dated Nov. 14, 1893, the letter was signed “W.K.L. Dickson.” She knew him as the head photographer at Thomas Edison’s New Jersey laboratory at a time when Edison was racing against competitors to establish himself as the father of motion pictures — as if, she says, having invented the light bulb and the phonograph wasn’t enough.

Dickson wanted to know the status of a copyright application he’d submitted to the Librarian of Congress, Ainsworth Rand Spofford, several weeks earlier. At the time, Spofford was also head of copyright operations.

The application was for a motion picture Dickson described only as “Kinetoscopic Records.” Dickson said the pictures contained in his letter were samples from the film. He had recorded them on a new machine perfected in Edison’s lab.

The machine could take 40 pictures a second, each an inch by three quarters of an inch in size. Imprinted on film stock and viewed through a kinetoscope — another Edison breakthrough — the images appeared to move. Dickson was making new films daily, he wrote, and he wanted to protect the lab’s work from the competition.

Kluge Center scholar Claudy Op den Kamp surveys notes from her research at the Library on early motion pictures. Photo courtesy of Claudy Op den Kamp.

Op den Kamp caught her breath, then cried out. In her hands, she held evidence from the birth of American cinema, a piece of paper that solved a longstanding mystery: What was the first U.S. motion picture ever copyrighted?

For years, scholars had known that an unidentified film registration had been made in 1893. But no one had been able to tie that registration to an actual motion picture title with any kind of certainty — until now.

Mike Mashon, head of the Library’s Moving Image Section, came running from a nearby office after hearing Op den Kamp’s cry. “It was a wonderful moment,” he says.

To the uninitiated, motion picture copyright might seem an arcane subject. But not to film scholars. For decades, they’ve mined copyright records at the Library — home to the U.S. Copyright Office — to piece together the story of early cinema. Under copyright law, registrants have to submit copies of their works when they apply.

When Dickson and other early producers registered, they couldn’t have known they were documenting the start of a world-changing industry.

“It only becomes clear in retrospect,” Mashon says. “But it’s from those early efforts that global cinema eventually emerges. Copyright has played an incredibly important role in preserving the record.”

Edison patented an extraordinary 1,000-plus inventions in his lifetime and zealously used legal means to protect his achievements. Dickson himself had been registering photographs with Spofford for years. So it’s not surprising Edison’s lab turned to copyright for its films.

Now, we know from Op den Kamp’s research that the first copyrighted motion picture was Edison’s “The Blacksmith Shop,” also known as “The Blacksmith Scene” or “The Blacksmithing Scene.” It runs just under 30 seconds.

The second film copyrighted, also from Edison’s lab, has long been known. Registered on Jan. 9, 1894, and inscribed in the official copyright record book as “Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze,” it’s often called “Fred Ott’s Sneeze.”

A still frame from “Fred Ott’s Sneeze.”

Ott was an employee in Edison’s lab, and he’s filmed sneezing as part of the lab’s motion picture experimentation. Prints submitted with the registration were transferred from copyright archives to the Library’s collections in the 1940s, and the Library has often displayed the prints and written about the film.

Although Spofford recorded a registration in 1893 as “Edison Kinetoscopic Records” — the same registration Dickson was asking about — neither Dickson’s original letter nor any prints from the film were known to exist. Until the blacksmith pictures dropped onto the table in front of Op den Kamp.

A lecturer in film and intellectual property at Bournemouth University in England, she was in residence at the Library’s John W. Kluge Center for six months this year to study Spofford’s role in the formation of the Library’s paper print collection — rolls of photographic contact paper the earliest producers submitted to register motion pictures.

Most early films were made on nitrate stock, which is highly flammable and prone to deterioration — the Library didn’t have the capacity to house them safely at the time. Nor did a category exist in copyright law for motion pictures until 1912.

Pioneering producers, starting with Edison, exposed their nitrate film negatives on rolls of photographic contact paper to register them, mostly as photographs, a category established in 1865.

The Library has about 6,500 paper prints — now including the blacksmith images — more than any other institution in the world by far. They’re a goldmine for researchers, because most nitrate films no longer exist.

That is not the case, however, for “The Blacksmith Shop.” Business magnate Henry Ford, Edison’s close friend, had a copy, and it survived. The Museum of Modern Art later preserved it.

“The idea that Ford had that copy, that Edison perhaps gave it to him or sent it to him, shows that Edison deemed it special,” Op den Kamp says.

It even made its way onto the Library’s National Film Registry in 1995. According to the registry, it features the first screen actors in history, one of whom is allegedly John Ott, brother of Fred, and another Edison employee.

Shown to audiences in Brooklyn, New York, on May 9, 1893, the film is also considered the first of more than a few feet to be exhibited publicly. “It shows living subjects portrayed in a manner to excite wonderment,” a Brooklyn newspaper reported the following day.

For Op den Kamp, connecting “Edison Kinetoscopic Records” from the copyright record book to “The Blacksmith Shop” didn’t involve dangers beyond a little dust. But her quest did have an almost Indiana Jones quality to it.

By the time she opened Dickson’s letter, she’d consulted around 30 staff experts, current and retired; used five reading rooms; and become intimately familiar with evolving copyright archival practices. All this led her to request five pallets from storage from the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, each containing 50 boxes, each associated with 2,000 registrations. And inside one of the boxes, she found the letter.

“It sat exactly where it was supposed to sit,” Op den Kamp says. She just had to figure out its path over the past 129 years.

Film scholars, she says, had long assumed “Kinetoscopic Records” implied multiple motion pictures. “The Blacksmith Shop” was strongly suspected to be among them. Other contenders included Edison’s

“Carmencita,” “Caicedo” and “Serpentine Dance” films.

“We now know that ‘records’ meant the multiple images in strips,” she says, as in the sample in Dickson’s letter.

“In some ways,” Mashon says, “the letter Claudy found is the Big Bang. Everything sort of flows from that. It was exciting to be part of that discovery.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

October 13, 2022

Crime Classics: Ed Lacy’s Edgar Award-Winning “Room to Swing”

“Room to Swing” is the newest addition to the Library’s Crime Classics series. Cover art adapted from Federal Art Project poster advertising the Sioux City Camera Club.

This is a guest post by Hannah Freece, a writer-editor in the Library’s Publishing Office.

“I broke par in Bingston.”

With this enigmatic statement, private eye Toussaint Moore opens “Room to Swing,” Ed Lacy’s Edgar Award–winning 1957 novel, the newest addition to the Library of Congress Crime Classics series.

It’s the hard-hitting story of a Black detective battling racism, a murder frame-up and the mysteries of an early reality television series about unsolved crimes. It’s a compelling story, popular when it was released in midcentury America, and the most influential of Lacy’s prolific career.

The narrative wastes no time. After that one-sentence opener, Moore continues, “It took me less than a minute to learn all I wanted to know—that I’d made a mistake by coming here.”

Here’s the set-up: A private detective in Harlem, “Touie” Moore is hired by the producers of a true crime reality television show to tail a suspect. When Moore finds his quarry dead—and himself framed for the crime—he must travel to the suspect’s hometown in fictional Bingston, Ohio, to solve the case. He encounters hostility and suspicion from the town’s white residents who balk at cooperating with a Black detective. To clear his name, Moore returns to New York to trap the murderer and confront his accusers.

Lacy was the pen name for Leonard S. Zinberg, a New Yorker who knocked out more than two dozen tough-guy crime novels published as paperback originals (“Go for the Body,” “Shakedown for Murder,” “Sin in Their Blood”) and more than one hundred short stories in a career that spanned nearly three decades. He was Jewish, married to a Black woman, a communist for many years, and an early and ardent advocate of civil rights for Black Americans. (Ralph Ellison, who moved in many of the same New York literary and social circles, reviewed Zinberg’s first book in 1940 in New Masses, a Marxist magazine.) When Zinberg died in Harlem of a heart attack in 1968 at age 56, the New York Times reported his inexpensive books, part of the midcentury love affair with pulp fiction, had sold more than 28 million copies.

He wrote “Swing” in mid-career, earning a footnote as the first white writer to place a Black detective at the center of a noir mystery. Published in 1957, it won the Edgar Award the following year for the best mystery novel.

As Crime Classics series editor Leslie S. Klinger describes in his introduction, the noir genre features “cynical, morally ambiguous protagonists [who] often found themselves caught in a whirlpool of events, slowly sucked into disaster.” Lacy created a tense drama in which Moore fights unseen forces—not only the true killer, but the racism that pervades American society.

While Lacy was not writing from lived experience, he made an earnest effort to capture the unique struggles of a Black man in the 1950s. Moore’s simultaneous skepticism and determination to exonerate himself place him firmly in the hard-boiled tradition.

Lacy was also innovative in setting “Swing” in the context of a reality television show called “You—Detective!” The producer who hires Moore describes the show as follows: “We rehash some unknown but factual crimes, and offer a reward if any viewer can nab the criminal. It’s been done before; you’ve probably seen similar shows.”

Unidentified actors recording “Gang Busters,” 1950. Phillips H. Lord Collection. National Audio-Visual Conservation Center.

Modern audiences surely have, but in 1957, the format was still novel. The concept of a true crime program with audience participation had its roots in radio. The “Gang Busters” radio show debuted in 1935 featuring dramatized plots pulled from the headlines. Actors portrayed key figures in each case, including heroic law enforcement officers, all accompanied by thrilling sound effects: sirens, whistles, gunfire, and fisticuffs. The show was wildly popular, ran for two decades, coined the phrase “coming on like gang busters” and sought to valorize the police while teaching audiences that “crime does not pay.”

The show, the creation of veteran radio star Phillips H. Lord, also featured descriptions of real fugitives gleaned from local police departments and the FBI. Listeners were encouraged to contact law enforcement with any information, just as viewers are in the fictional “You—Detective!”

FBI Wanted bulletin for Ruth McElvain, 1954. Phillips H. Lord Collection. National Audio-Visual Conservation Center.

The success of “Gang Busters” led to its television adaptation in 1952. Other TV programs soon followed, though it would be decades before the genre’s longest-running shows, “America’s Most Wanted” and “Cops,” premiered in 1988 and 1989, respectively. The popularity of true crime in new formats like the podcast “Serial,” which debuted in 2014, shows Americans’ enduring enthusiasm for the genre. (“Gang Busters” was added to the National Recording Registry in 2008.)

With its republication of “Room to Swing,” the Library celebrates another under-recognized masterpiece, the 12th in the Crime Classics series. Launched in 2020, the series features some of the finest – if faded from popular memory – American crime writing from the 1860s to the 1960s. The list includes “The Conjure-Man Dies,” “That Affair Next Door,” and “Last Seen Wearing.” Drawn from the Library’s collections, each volume includes the original text, an introduction, author biography, notes, recommendations for further reading and suggested discussion questions from mystery expert Klinger.

Crime Classics are published by Poisoned Pen Press, an imprint of Sourcebooks, in association with the Library of Congress. “Room to Swing,” published on October 4, is available in softcover ($14.99) from booksellers worldwide, including the Library of Congress shop .

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

October 6, 2022

Researcher Story: Julie Centofanti

Julie Centofani. Photo courtesy of the author.

Julie Centofanti, a biology student at Youngstown State University, started a club at her university in 2020 to transcribe historical documents included in the Library’s By the People project. A longer version of this interview appears on the Signal blog.

How did you find out about By the People?

I’m a member of the Youngstown State University Sokolov Honors College, and we are required to earn 60 volunteer hours per year. Serving the community can be challenging for any college student, and the COVID-19 pandemic made it even harder.

So, I did what any college student would do: research virtual volunteer opportunities on the internet. Through my travels, I found BTP. I have always loved learning about history, and I discovered that the Library offers the perfect way to preserve history and earn volunteer hours!

Tell us about your club.

In summer 2020, I met with Mollie Hartup, the associate director of my honors college, and we discussed possibly hosting a virtual event for other honors students to transcribe historical documents. In August, we organized the first transcribe-a-thon on WebEx. Since then, we have hosted multiple transcribe-a-thons and now have biweekly two-hour meetings for students to earn volunteer hours in a virtual environment.

We start each meeting with a tutorial in which we review available BTP campaigns and documents to transcribe and review. Afterward, students log into the Library, choose a campaign and transcribe. During the session, students can ask questions by sharing their screens, and they collaborate to determine words or phrases that may be difficult to read.

At the end of the meeting, we discuss interesting documents we transcribed, along with the number of pages we transcribed or reviewed. Students earn Transcribing Club prizes, such as pins, pens and other gifts when they attend a certain number of meetings.

What are some interesting documents you’ve come across?

I have found countless documents interesting.

The first project I worked on was the Theodore Roosevelt campaign. I have always enjoyed reading about the personal documents that Roosevelt received, either from family or friends. While transcribing, I found an 1899 letter he received when he was governor of New York particularly interesting. It discusses the conditions of troops in the Philippines and promotions of exemplary officers.

As a biology student in the premedical track, I am also fascinated by health care from the past. Many documents in the Early Copyright Title Pages campaign discuss remedies for health problems. It is interesting to see similarities and differences in health care from the 1800s to today.

What advice do you have for first-time transcribers and students who might want to organize their own club?

For new transcribers, I would recommend treating each campaign or document with an open mind. Transcribing documents in cursive or illegible handwriting can be challenging, but each document has its own story.

To start, I would suggest a short document that is easy to understand. This will build confidence and a sense of accomplishment. If you cannot complete a page, save your work and move to the following document. Your time and dedication to the Library will be greatly appreciated.

For students looking to organize a college transcribing club, I would recommend reaching out to other students through a university newsletter, online forum or promotional posters or forming a group within your major.

Then, create a transcription tutorial on paper or video, so students are not intimidated or nervous to begin transcribing. The Library has resources to help you put together a transcription presentation. And I created a tutorial to use during my meetings.

From there, set up a meeting date. In a university setting, your transcribing club can be virtual or in person. Many students enjoy collaborating in person, so they can meet other students and help each other with difficult documents.

In any case, it is imperative to encourage students as they first begin transcribing. To do this, ensure that the students choose a campaign they would like to learn about or something that relates to their major.

Another way to encourage students is to set goals for them to attend meetings. For example, we have Transcribing Club levels for students who attend meetings. Students who attend 15 meetings earn the Bronze Award, students who attend 20 meetings earn the Silver Award and students who attend 30 meetings earn the Gold Award. Students also earn small prizes for reaching a new milestone.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

October 3, 2022

Amelia Earhart, in History’s Hands

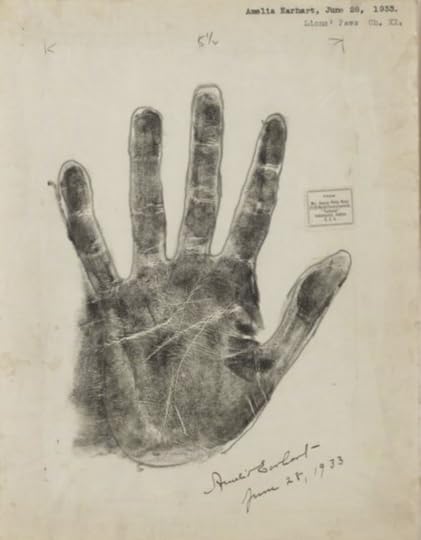

Amelia Earhart’s handprint, signed by famed pilot. June 28, 1933. Manuscript Division.

A shorter version of this story appeared in the July/August edition of the Library of Congress Magazine.

The best clues to a person’s character lie right in the palms of their hands. That, at least, is what Nellie Simmons Meier believed.

Meier, you see, was one of the world’s foremost practitioners of the “science” of palmistry in the 1920s and ’30s. She and other palmists thought they could divine one’s character, personality and, perhaps, even their future by studying the shape of the hands and the lines of the palms.

Meier was so renowned for her work that some of the world’s most famous folks — Albert Einstein, Eleanor Roosevelt, George Gershwin, Booker T. Washington and Susan B. Anthony, among others — sought her insight. Many trekked all the way to Tuckaway, her cottage in Indianapolis, for consultations.

Sitting in the parlor, Meier examined their hands, seeking clues to what made them tick. She also made prints of their hands and wrote character analyses based on her readings. In 1937, she published her work in a book, “Lions’ Paws: The Story of Famous Hands.”

Eventually, she donated a portion of her original material to the Library — the Manuscript Division holds autographed handprints and photographs of 135 notable figures as well as the character sketches she wrote for each.

In 1933, Meier examined a pair of hands that, wrapped around the controls of a Lockheed Vega 5B, helped make aviation history. Just a year earlier, Amelia Earhart had flown from Newfoundland to Ireland — the first solo, nonstop flight across the Atlantic by a woman. When visitors see Earhart’s handprint in the Library today, they often comment upon its size. Earhart stood 5 feet and either 7 or 8 inches (both are listed in official records) tall, about four inches taller than the average American woman in 1930, and the handprint gives an impression of athletic, physical capability.

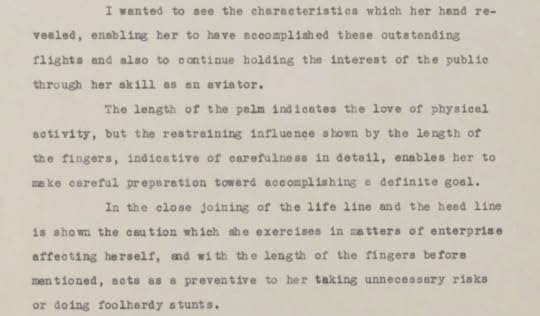

In her own examination of Earhart’s hands, Meier saw signs of a natural caution that, she wrote, “acts as a preventive to her taking unnecessary risks or doing foolhardy stunts.”

Part of Meier’s analysis of handprints: “I wanted to see the characteristics which her hand revealed…” Manuscript Division.

Yet, flying was inherently risky, and Earhart was pushing boundaries.

So it was that, four years after that meeting with Meier, Earhart took flight on another attempt to make history, this time as the first woman to fly around the world, aided only by navigator Fred Noonan.

Following a shakedown flight from Oakland, California, Earhart and Noonan departed Miami on June 1, 1937, in a twin-engine Lockheed Electra bound for Puerto Rico, South America and points far beyond. After covering more than 19,000 miles over the next month, the pair took off from Lae, New Guinea, on July 2, headed for the pin-drop-sized Howland Island, more than 2,500 miles away. The uninhabited island, little more than a coral atoll, covers less than one square mile and rises just 20 feet above the sea.

Amelia Earhart in the cockpit of a Lockheed Electra. Undated. Acme News Service. Prints and Photographs Division.

The U.S. Coast Guard cutter Itasca, anchored off Howland Island, made radio contact with the pair repeatedly over the course of seven hours in the early hours of July 2. The signal was eventually strong and the reception clear, with Earhart’s plane reporting at one point they were less than 100 miles from Howland. The Itasca sent up a smoke screen to help the pilot and navigator spot them in the early morning glare.

But something went amiss; the cutter and the plane never spotted one another. After a few hours, Earhart reported they were running out of fuel and still couldn’t find the island. Radio contact ended. By 11 a.m., the ship’s officers concluded the plane had gone down.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt immediately authorized the most extensive (and expensive) air and sea search in U.S. history. It turned up nothing. Earhart and Noonan were declared lost at sea by the end of the month. A government report concluded the pair had run out of gas and crashed in the open sea, but books, theories and searches continue to this day, spurred by radio signals that some say came from Earhart days after the plane went down. High-tech expeditions have searched the ocean floor around Howland Island, while others have focused on an uninhabited atoll 350 miles away, Nikumaroro, on the theory that the pair managed to land on a reef that was dry at low tide, were badly injured and survived for several days. None has been proven conclusively.

Today, though, Earhart’s pioneeering legacy lives on, and the Library still preserves the images of those hands that made history.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 28, 2022

It’s About (Danged) Time: Lizzo at the Library!

Lizzo checks the sheet music while playing one of the LIbrary’s flutes. Photo: Shawn Miller.

It all started with a tweet.

Last Friday, Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden saw that the one and only Lizzo was coming to D.C. for a concert. The pop megastar is a classically trained flautist. The Library has the world’s largest flute collection.

Taking to Twitter, the Librarian played matchmaker, tagging Lizzo in a tweet about the world-class flutes.

“Like your song,” she tweeted, “they are ‘Good as hell.’ ”

One of about 1,700 flutes in the collection, she teased, is the crystal flute made for President James Madison by Claude Laurent — a priceless instrument that Dolley Madison rescued from the White House in April 1814 as the British entered Washington, DC during the War of 1812.. Might she want to drop by and play a few bars?

Lizzo did a hair toss, checked her nails and took to Twitter herself. The 34-year-old has been training on the flute since she was a child. As a college student, she played in the University of Houston marching band. She even performed online with the New York Philharmonic orchestra during the pandemic.

“IM COMING CARLA! AND I’M PLAYIN THAT CRYSTAL FLUTE!!!!!” she tweeted the next day.

She pulled up to the Library on Monday. Hayden and the Music Division staff ushered her into the flute vault, giving her a tour of the highlights. It’s quite the sight. The main body of Library’s collection was donated in 1941 by Dayton C. Miller, a renowned physicist, astronomer and ardent collector of flutes who was intrigued by their acoustics. His collection includes a walking stick flute, which may now be on Lizzo’s wish list for the holidays.

Now. About that crystal flute.

Laurent was a French craftsman, a clockmaker by trade, who was born in the late 18th century. He took an interest in flutes as a pastime. He patented a leaded glass flute in 1806. Most flutes at the time were made of wood or ivory, but Laurent’s glass invention held its pitch and tone better during changes in temperature and humidity. They were popular for a few decades, but he was almost alone in making them and they faded from popularity after flutes began to be made of metal in the mid-19th century. Today, only 185 of his glass flutes are known to survive, and his crystal flutes are even rarer. The Library holds 17 Laurent flutes, by far the largest collection in the world.

They were near the height of their popularity when Laurent sent a particularly elegant crystal flute to President Madison upon the occasion of his second inauguration. Its silver joint is engraved with Madison’s name, title and the year of its manufacture — 1813. It’s not clear if Madison did much with the flute other than admire it, but it became a family heirloom and an artifact of the era.

President James Madison’s crystal flute, engraved with his name and the year it was made — 1813. Photo: Library of Congress.

Before Lizzo arrived, the Library’s curators in the Music Division made sure that it could be played safely and without damage. This sort of thing is not as unusual as it might sound. Many of the Library’s priceless instruments are played every now and again, even the five stringed instruments by Antonio Stradivari. Those, in fact, were given to the Library by Gertrude Clarke Whittall with the stipulation that they should be played from time to time. Music fans can hear the Library’s Stradivari and some of our other classic instruments — the 1654 Nicolò Amati violin and Wanda Landowska’s Challis clavichord — during the fall 2022 Concert Series.

So, Monday. Our two stars meet cute.

Lizzo reverently took Madison’s crystal flute in hand and blew a few notes. This isn’t easy, as the instrument is more than 200 years old. She blew a few more when she was in the Great Hall and Main Reading Room. Then, reaching for a more practical flute from the collection, she serenaded employees and a few researchers. It filled the space with music as sublime as the art and architecture.

Cameras snapped and video rolled. For your friendly national library, this was a perfect moment to show a new generation how we preserve the country’s rich cultural heritage. The Library’s vision is that all Americans are connected to our holdings. We want people to see them.

Lizzo with Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden in the Library’s flute vault. Photo by Shawn Miller

So when Lizzo asked if she could play the flute at her Tuesday concert in front of thousands of fans, the Library’s collection, preservation and security teams were up the challenge. When an item this valuable leaves any museum or library, for loan or display in an exhibition, preservation and security are the priorities. At the Library, curators ensure that the item can be transported in a customized protective container and a Library curator and security officer are always guarding the item until it is secured once more.

For obvious reasons, we don’t say much more about security in public. But when the Library sent Thomas Jefferson’s Koran to the World Expo in Dubai last year, conservation, preservation and strict environmental requirements were enforced. The Library and the State Department executed a plan to transport and securely display the Koran. A Library professional with experience preserving and maintaining the security of important cultural items accompanied the Koran at every step.

The same sort of security was in place for the Madison flute to rejoin Lizzo onstage at Capitol One Arena. When Library curator Carol Lynn Ward-Bamford walked the instrument onstage and handed it to Lizzo to a roar of applause, it was just the last, most visible step of our security package. This work by a team of backstage professionals enabled an enraptured audience to learn about the Library’s treasures in an exciting way.

As some of y’all may know I got invited to the Library of Congress,” Lizzo said, after placing her own flute (named Sasha Flute) down on its sparkling pedestal, which had emerged minutes earlier from the center of the stage. Following the aforementioned, highly popular Twitter exchange between Lizzo the Librarian of Congress, the crowd knew what was coming.

“I want everybody to make some noise for James Madison’s crystal flute, y’all!” They made more noise than the instrument, having been at the Library for 81 years, has been exposed to in quite some time. Maybe ever.

She took it gingerly from Ward-Bamford’s hands, walked over to the mic and admitted: “I’m scared.” She also urged the crowd to be patient. “It’s crystal, it’s like playing out of a wine glass!”

Lizzo played just a few notes on the flute, “trilling” the instrument, but she threw her signature twerk into the short performance, sending the audience into a fresh frenzy.

“We just made history tonight!” she exclaimed. “Thank you to the Library of Congress for preserving our history and making history freaking cool! History is freaking cool you guys!”

And now, thanks to Lizzo, it’s just that much cooler.

September 27, 2022

The Work of George Chauncey, LGBTQ Historian and Kluge Prize Honoree

George Chauncey took to the stage in the Library’s Great Hall last Wednesday night to formally accept the 2022 Kluge Prize for Achievement in the Study of Humanity. It was a black tie event that had an emotional undercurrent that belied both the formal wear of the crowd and the formal nature of academic dinners.

Chauncey, the DeWitt Clinton Professor of American History at Columbia University and director of the Columbia Research Institute on the Global History of Sexualities, is the first LGBTQ scholar to win the Kluge’s prestigious $500,000 prize. After four decades helping pioneer the field in academia – and of testifying or filing briefs in court cases that helped establish gay rights – the awards ceremony had the feeling of a victory lap.

“With pride tonight, it is my honor to say that Dr. Chauncey is the first scholar – the first scholar, not the last – in LGBTQ+ studies to receive the Kluge Prize,” said Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress, before draping the Kluge medal around Chauncy’s neck, in front of an applauding crowd of Madison Council members, members of congress and invited guests. “The Library of Congress’ mission is to connect and engage with all Americans, and that means telling the rich, diverse stories of all citizens of this country.”

Chauncey, acknowledging the award by joking that he was “never going to win an Olympic medal,” thanked friends, family and colleagues, but most emotionally his spouse, Ronald Gregg. Gregg, a film historian and director of the master’s program in Film and Media Studies at Columbia, met Chauncey in Chicago three decades ago. They have been together for 28 years and married for eight – the latter due in no small part due to Chauncey’s key work on the Supreme Court cases that legalized gay marriage. Without Gregg, Chauncey said, “I could barely imagine my life.”

Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden bestows the Kluge Medal on George Chauncey, while Kluge Director Kevin Butterfield looks on. Photo: Shawn Miller.

“I gratefully accept this prize not just for myself but on behalf of a field of study and a group of courageous scholars whose work on the LGBTQ past was marginalized for far too long,” he said in his 15-minute acceptance speech. “To have the Library of Congress recognize the scholarly quality and significance of this field is profoundly important.” 18:57

Chauncey’s research over the decades has shown that laws criminalizing homosexuality are not millennia-old traditions of western society, but mostly creations of mid-century American conservative politics, beginning in the Depression and continuing for the next half century.

“Chauncey’s work gives us that story that we need to tell about ourselves so that we can be our better selves,” said Martha S. Jones, a professor of history at Johns Hopkins University, in an interview before the ceremony.

“Gay New York” is Chauncey’s best known book.

Chauncey’s landmark 1994 book, “Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World 1890-1940,” documented that in the first three decades of the 20th century gay life in many American cities was often relatively open and tolerated, reaching a peak in the Jazz Age 1920s. During Prohibition, speakeasies serving illegal liquor became a popular attraction for millions of otherwise law-abiding citizens, creating an realm where social rules were far more relaxed.

In this environment, openly gay, cross-dressing acts became popular (particularly in New York), making camp humor standard fare in many nightspots. Singers such as Gladys Bentley (who performed wearing a tuxedo) and Gene Malin, who performed camp novelty songs, were headliners. The “pansy” craze swept the east coast, drawing thousands gay and straight partygoers of all races and economic backgrounds to drag balls.

At the same time, Chauncey wrote, the societal understanding of what made a man “gay” was profoundly different than today for a number of reasons. For one, the growth of cities brought millions of people, many of them single young men, into urban environments and away from the strictures of family and small-town life.

In these cities, societal norms of the era also prohibited women from being in many workplaces, almost all saloons (unless they were prostitutes) or even to be unaccompanied in public. In these overwhelmingly male environments, men who sometimes or even frequently had sex with other men were not considered to be homosexual unless they were openly effete, known at the time as “pansies” or “faeries.”

In “Gay New York,” Chauncey demonstrated this now-forgotten world, showing that particularly among working-class men there was far more acceptance of such relationships, particularly if they were private.

Only a reactionary wave of laws that began in the austerity of the Depression created an entire class of people as “gay” and then discriminated against them in almost every facet of society. This created the realm of the gay “closet.”

Chauncey, born in the 1950s, grew up as the son of a Presbyterian minister in the Deep South who campaigned for civil rights. He learned early that stands for social justice were often unpopular and greatly discouraged, sometimes with violence.

He received his undergraduate and doctoral degrees from Yale University. After a difficult time finding work as a young historian specializing in what was then considered to be a small and unimportant field, he landed a teaching position at the University of Chicago from 1991 through 2006. He returned to Yale as the Samuel Knight Professor of History & American Studies from 2006 to 2017. He then moved to Columbia.

In court, he’s been involved in 30 cases that targeted gay rights, testifying or filing amicus briefs about his research. Four of those cases went to the U.S. Supreme Court, including landmark cases Lawrence v. Texas in 2003, which overturned the nation’s remaining sodomy laws; and the marriage equality cases, United States v. Windsor in 2013 and Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015.

Chauncey joins a prestigious group of Kluge winners that includes the most recent honoree, Danielle Allen, a political theorist at Harvard University; Jürgen Habermas, the German philosopher; Fernando Henrique Cardoso, a former president of Brazil; Drew Gilpin Faust, a Harvard historian; and John Hope Franklin, the veteran scholar of African American history.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers