Library of Congress's Blog, page 24

May 2, 2023

LGBTQ+ at the LOC!

Lilli Vincenz on a personal camping trip. Photo: Unknown. Lilli Vincenz collection. Prints and Photographs Division.

Lilli Vincenz on a personal camping trip. Photo: Unknown. Lilli Vincenz collection. Prints and Photographs Division.

One evening in the late summer of 1961, a young woman named Lilli Vincenz walked into a “kind of a lesbian bar” called the Ace of Spades in Provincetown, Massachusetts. She had never been in such an establishment before, and this was a “very strange-looking shack, half-hidden behind a restaurant, with all kinds of old utensils hanging on the outside as ornaments.”

She was never the same again.

“I feel different,” she wrote that night in her journal. “To look at someone and smile and see the smile returned by a girl — this has never happened to me before. … Oh, it was wonderful to flirt with a girl!”

Vincenz, whose papers are preserved at the Library, would go on to be one of the nation’s most influential lesbian activists in the early days of the gay rights movement. Her delightful moment of self-discovery is just one dot in the Library’s sprawling collection of LGBTQ+ material that captures the joy, pain and perseverance of a demographic that has challenged the nation to uphold its post-Enlightenment ideals of fair play.

“Vincenz is a really important collection,” said Ryan Reft, who, along with fellow historian Elizabeth Novara, oversees LGBTQ+ collections in the Manuscript Division. “First, her papers, along with those of activist Frank Kameny, serve as a window into the homophile movement of the midcentury and its fight for equal rights, as well as documenting the developments in the LGBTQ+ community that followed. Second, Vincenz also provides a lesbian voice, which our collections sometimes lack. While one can discover in our collections pockets in which notable figures appear, we are working to diversify the voices archived in the division generally but particularly as it pertains to LGBTQ+ history.”

Frances Benjamin Johnston

. 1896 Self portrait. Prints and Photographs Division.

Frances Benjamin Johnston

. 1896 Self portrait. Prints and Photographs Division.Major American lives and subjects fill significant collections — Frances Benjamin Johnston, Leonard Bernstein, Alvin Ailey, Alla Nazimova, Cole Porter, the AIDS Memorial Quilt Archive — as well as midcentury activist groups such as the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society.

Behind the big names, there are countless moments of smaller lives and subjects. There is the tiny collection of photographs of gender-nonconforming older adults by photographer Jess Dugan from the 2018 book “To Survive on This Shore.” There are wonderful moments, such as the recording of Audre Lorde reading her poetry in a 1982 appearance in the Coolidge Auditorium.

Today, the Library collects LGBTQ+ material at the research level, and the Pride in the Library: LGBTQ+ Voices in the Library’s Collections research guide is an excellent starting point. There also are specially curated exhibits such as “Serving in Silence: LGBTQ+ Veterans.”

“I’m glad that we’re able to talk now,” said Tedosio Louis Samora, a U.S. Army veteran who served in the 519th Military Intelligence Battalion in Vietnam, in a filmed interview with the Veterans History Project. Samora, part of a Mexican-American family that has a tradition of military service, discussed the confrontational, even violent emotions involved in coming out to his brothers, who also served in the conflict.

Bayard Rustin at a press conference on the Civil Rights March on Washington. Photo: Warren K. Leffler. Prints and Photographs Division.

Bayard Rustin at a press conference on the Civil Rights March on Washington. Photo: Warren K. Leffler. Prints and Photographs Division.The nation’s engagement with queer issues began almost as soon as the first settlers landed at Jamestown in 1607. Take, for instance, the 1629 Virginia General Court case of Thomas(ine) Hall. Hall was an intersex person whose genitalia and gender identity confounded local authorities. A judge finally ruled that Hall was both a “a man and a woeman” and ordered Hall, then about 28, to always wear a man’s breeches and shirt and a woman’s apron and cap.

Skip to a summer night in 1870 and we find Walt Whitman, the nation’s poet, dashing off a few quick lines to Peter Doyle, his intimate companion two decades his junior: “Good night, Pete, — Good night my darling son — here is a kiss for you, dear boy — on the paper here — a good long one.” The final “o” is smudged, as if Whitman did indeed give the page a smack.

A generation later, Johnston — a renowned photographer of everything from U.S. presidents to architecture — took a provocative self-portrait. She posed as a “new woman” in 1896: Hiking her skirt to the knee, holding a beer stein in one hand and a cigarette in the other. She would go on to become not just a pioneer of photography but as a lesbian icon.

In the 1910s, few people were more glamorous than stage actress, director and producer Eva Le Gallienne. Among her other female lovers, she sometimes dated the equally glamorous actress and producer Alla Nazimova.

Alla Nazimova, one of the most famous actress in the first three decades of the 20th century. Photo: Unknown. 1908. Prints and Photographs Division.

Alla Nazimova, one of the most famous actress in the first three decades of the 20th century. Photo: Unknown. 1908. Prints and Photographs Division.Nazimova’s papers at the Library document her larger-than-life persona. A Russian actress and accomplished violinist who studied under the legendary actor and director Konstantin Stanislavski, she immigrated to the U.S. and became a huge stage and film star. In 1918, she was making $13,000 per week, even more than Mary Pickford.

She was also “Broadway’s most daring lesbian,” according to “The Sewing Circle,” a 1995 history of “Female Stars Who Loved Other Women” by Axel Madsen. (She had a “lavender marriage” for several years to help disguise her relationships.)

Most famous for her work in the plays of Ibsen and Chekhov, she produced and starred in the avant-garde silent film “Salome,” a 1922 adaptation of the Oscar Wilde play. It was a disaster when released but was added to the National Film Registry in 2000 and today is regarded as a key moment in the history of gay cinema. In a 2013 book, “The Girls: Sappho Goes to Hollywood,” author Diana McLellan dubbed Nazimova “the founding mother of Sapphic Hollywood.”

Nazimova’s most lasting contribution to Hollywood-wide lore may have been her Sunset Strip estate, which she called, tongue firmly in cheek, “the Garden of Alla.” It was a huge mansion on 2.5 acres and a haven for exclusive parties. She sold it in the late ’20s with the stipulation she could stay rent-free for the rest of her life. The new owners added an “h” to “Alla,” to complete the Islamic reference, and two dozen private villas.

It became a prominent (often scandalous) backdrop to the golden age of Hollywood, the subject of histories and novels, mentioned in films and plays. A name-check of guests is astonishing: Clara Bow, Errol Flynn, Greta Garbo, Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Frank Sinatra, D.W. Griffith, Barbara Stanwyck, Eartha Kitt and Ronald Reagan.

By the 1940s, Nazimova was in her 60s and her career, a good bit of her health (she’d had cancer) and most of her income was gone. Still, she was the affectionate godmother of actress Nancy Davis, who later married Reagan and became first lady of the United States. And she was living openly with her longtime partner, actress Glesca Marshall.

A new era began just a few years later, with activists beginning to wage battles for open acceptance at work, play, military service, worship and marriage. The Daughters of Bilitis, a lesbian activist group, was formed in 1955, published a magazine called The Ladder and was a mainstay to early activists such as Vincenz.

Frank Kameny at DC’s Capital Pride Parade in 2010. Photo: Elvert Barnes.

Frank Kameny at DC’s Capital Pride Parade in 2010. Photo: Elvert Barnes.Which brings us to the vast collection of Frank Kameny, founder of the Mattachine Society of Washington.

A native New Yorker, gay World War II combat veteran and a Harvard-educated astronomer, he became one of the nation’s most influential gay voices from the late 1950s until his death in 2011. He was particularly involved in the “homophile movement” of the 1960s before the Stonewall Riot in 1969 in New York created the modern gay-rights era. So profound are his contributions to the American cause that his house in northwest D.C. — the Mattachine Society’s headquarters, salon and nerve center — is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

His papers at the Library are vast — more than 56,000 items. Perhaps his greatest victory came in 1973, when his decadelong campaign to have homosexuality removed from the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders finally bore fruit. The organization declared that being gay was no longer considered a mental illness.

“VICTORY!!!!” he wrote in the subject heading of a Dec. 15, 1973, letter to his friends and supporters. “We have been ‘cured’!”

He might have been premature in predicting the acceptance of LGBTQ+ life in the U.S., but his enthusiasm at the moment is preserved at a pivotal moment in national history.

This article appears in the May-June issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

April 27, 2023

Jeffrey Yoo Warren: Seeing Lost Enclaves

This is a guest post by Sahar Kazmi, a writer-editor in the Office of the Chief Communications Officer. It also appears in the March-April issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

The Library boasts many ways history-lovers can immerse themselves with its treasures from afar. They can explore online collections, tune in to virtual lectures, discover extraordinary tales on our blogs.

Now, 2023 Innovator in Residence Jeffrey Yoo Warren is building another doorway to the past with his project, “Seeing Lost Enclaves: Relational Reconstructions of Erased Historic Neighborhoods of Color.”

Using 3D modeling techniques and insights from the collections, Yoo Warren is developing a virtual reconstruction of the once-bustling Chinatown district in Providence, Rhode Island. A vibrant enclave 100 years ago, the Chinatown of Providence largely has been erased from historical memory.

In his work with the Library, Yoo Warren will expand his research to include other early 20th-century Chinatowns in places such as New Orleans, Denver and Truckee, California.

Using the Library’s archival photos, newspapers, maps, film and audio recordings as well as work with local communities, Yoo Warren’s “relational reconstruction” process aims to make these places “visitable” again, if only virtually. He’ll also experiment with multisensory elements like virtual weather and soundscapes.

The full effect, he hopes, will give audiences a visceral — and maybe even deeply personal — feeling of walking into a forgotten reality.

Although his 3D visualization is centered on Chinatowns, Yoo Warren’s work also will produce a “relational reconstruction toolkit” to inspire the public to develop similar recovery efforts for other ancestral spaces. The toolkit will feature resources and tutorials on using the Library’s place-based materials to reclaim lost histories through immersive digital reconstructions.

As an artist and educator, Yoo Warren believes the historical erasure he’s addressing is not only a challenge of archival documentation but a matter of community meaning and loss. In creatively rebuilding the sights, sounds and emotion of lost spaces, his work will help the Library enrich the nation’s cultural memory and, with some technological help, construct another bridge between the records of the past and the potential of tomorrow.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

April 20, 2023

Midori: Music and the Instrument That Makes It

This is a guest post by Midori, a classical violinist who made her debut with the New York Philharmonic at age 11. She plays the 1734 Guarnerius del Gesù “ex-Huberman” and uses four bows — two by Dominique Peccatte, one by François Peccatte and one by Paul Siefried. This article appears in the March-April 2023 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

What is the relationship between musicians and musical instruments and the music that, together, they ultimately produce? To me, that is almost a spiritual question, of alignments, of meldings of purpose.

I consider my violin to be my partner in music-making. It is almost 300 years old, with so much history animating it. Any number of renowned violinists have played this august instrument over time, so that it is a repository of our legacy of iconic music — a keeper of many secrets, as it were — now abetting me in my own forays as an interpreter of so many amazing works that have enriched and continue to enrich humankind through the centuries.

For me, this instrument is all but alive. When I hold my violin in my hands, I know it so well. I feel that the violin has a personality, it has force of character, and its particularity has become a part of what I do.

After several hundred years, this violin does not merely defer. A long-lived instrument, one that requires ongoing maintenance (at certain times it must be deeply cleaned, or a new bridge is needed, the fingerboard planed, etc.), it is changeable and it is challenging. It plays differently from day to day, depending on the weather and the atmospheric conditions in a performance space. But that constant challenge, of responding to the different colors this great instrument provides in different circumstances — it inspires me.

An instrument of so many moods and needs, my violin forces me to work hard to commune with it successfully. In return, it has so much to offer, an incredible range of colors and sounds. Its sound can be rich but also velvety at times and light as a feather at other times. The music it is prepared to yield is crystal clear, deep and complex — all at the same time.

A great instrument, tested over centuries, ever changing and ever deepening, does not merely succumb to any player, but through joined effort it offers great rewards. My violin may be a “diva” (as my luthier calls it), but I respect its lineage and its prideful uniqueness. Music-making is a living process, and I work hard to bring out this instrument’s brilliance, allowing our music to reach toward a higher place.

This partnership spurs me ever forward, now over decades. I continue to strive to interpret great compositions of many eras both thoughtfully and boldly, while carrying our art form forward into future realms. In today’s increasingly interconnecting world, I pursue the added goal of bringing music to people who in some ways are left out, who often don’t have ready access to live performance (because of trying circumstances or where they live) — in the doing providing joy, consolation, solace, healing, contemplation. My violin, finicky as it may be, has survived and thrived over centuries, and so long as I treat it carefully and lovingly, we can sing out together, sharing an endless range of timeless ideas and beauty — and, hopefully, inspiration.

This article first appeared in the March-April issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

April 17, 2023

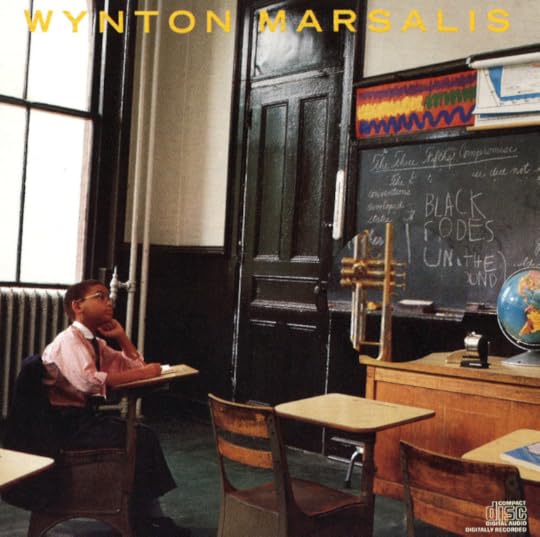

Wynton Marsalis, “Black Codes” and Thoughts on the Highway

It is midafternoon on a recent weekday and jazz legend Wynton Marsalis is driving across the Southwest, taking the call on speakerphone that his 1985 album, “Black Codes (From the Underground),” has been inducted into the 2023 class of the National Recording Registry.

“Where are we now?” he asks fellow passengers in the car. “New Mexico?”

“New Mexico,” a voice confirms.

Travel has been hectic of late. Marsalis, trumpeter, bandleader, the managing and artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York and perhaps the most internationally recognized jazz musician of the era, has just wrapped up a tour in Asia with multiple stops in South Korea and Japan.

The man is 61. He’s been working gigs for 48 years, since he was a 13-year-old child prodigy on Bourbon Street. He’s recorded more than 60 jazz and classical albums, won the Pulitzer Prize, 9 nine Grammys and been a star of numerous documentaries, not least Ken Burns’ “Jazz.”

Now, he’s on the road again, heading east into the middle of America, empty desert stretching out in all directions.

“We left Los Angeles at 12 o’clock midnight — I mean, Santa Barbara — and now it’s 1:51 p.m., where we are, and we’re just in New Mexico.” He’s got time to chat, he laughs.

“Black Codes” is one of 25 pieces inducted into the NRR this year, ranging from 1908 mariachi recordings to a 2012 release of a classical piece by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Ellen Taaffe Zwilich. The Library has nearly 4 million recordings; only 625 are in the NRR.

“Black Codes” is the first recording by Marsalis to make the list. He points out that after a career that spans five decades, the Library selected an album he recorded when he was 23.

“People like it, it’s an OK record,” he allows. “But it’s some (expletive) before I even learned how to play.”

This doesn’t come across as false modesty given his straightforward, cheerfully profane delivery, but as a common assessment of most people of a certain age — who among us wants to be reminded of our work product in our early 20s?

Still, he’s happy to reconstruct the basics.

The album was recorded in New York over four days in 1985. It was his sixth record. It’s seven songs of hard-swinging jazz that addressed, if in abstract fashion, the lingering societal effects of the Black Codes, the notorious post-Civil War laws that his native Louisiana and other Southern states used to keep black citizens in a violent state of oppression. One of his brothers, Branford, himself a renowned musician, played sax. His youngest brother, Jason, then just 7, is pictured on the album cover as a school student.

“A lot of 20th-century civil rights cases were based on the Black Codes, on laws that tried to politically undress the achievements of the Civil War,” Marsalis explains.

“From the Underground” refers to Black resistance to those laws: “No matter how defeated things seem, there’s always an idea in the pursuit of freedom that is subversive to anti-democratic thinking. I was very conscious of that (when recording).”

The album cover wasn’t subtle. It’s a schoolroom photograph of a lone black child (the aforementioned Jason Marsalis), gazing at a blackboard where the “Three-Fifths Compromise” — the constitutional measure that described enslaved Black people as three-fifths of a human being — was written out in chalk as the lesson of the day. Part of it is erased. Replacing it are words also written in chalk: “Black Codes (From the Underground).” A trumpet rests on the teacher’s desk.

On the album, the family and cultural inspirations are also practical.

Marsalis drew on his father’s history as a jazz musician and teacher in New Orleans, particularly a 1960s song called “Magnolia Triangle,” for the melody line of the title cut. The bass line was inspired by the classic New Orleans standard “Hey Pocky A-Way,” by The Meters.

“We live here for whatever our time is, and people represent us in different ways,” Marsalis is saying, the miles whizzing past. “The art forms, of course, speak across time. They tend to speak more successfully than philosophy because philosophy has to be written in a symbolic language that’s easily misconstrued. Art is much more direct.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

April 12, 2023

The 2023 National Recording Registry – Mariah Carey, Eurythmics, Jimmy Buffett, Wynton Marsalis, John Lennon (And Lots More)

Madonna’s cultural ascent with “Like a Virgin,” Mariah Carey’s perennial No. 1 Christmas hit, Queen Latifah’s groundbreaking “All Hail the Queen” and Daddy Yankee’s reggaeton explosion with “Gasolina” are some of the defining sounds of the nation’s history and culture that will join the Library’s 2023 class of the National Recording Registry, Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden announced today.

The 25 additions in the 2023 class span more than a century, from 1908 to 2012. They range from the first recordings of Mariachi music and early sounds of the Blues to radio journalism leading up to World War II, and iconic sounds from pop, country, rock, R&B, jazz, rap, and classical music. It also includes the first sounds of a video game to join the registry with the Super Mario Bros. theme.

Carey, Jimmy Buffett, Annie Lennox and Dave Stewart (the Eurythmics), Graham Nash, Wynton Marsalis and Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Ellen Taaffe Zwilich joined the Library for interviews about their defining works. You can see them in the video above and in longer interview segments on the Library’s social media channels. The interviews will be added to Library archives as well.

“The National Recording Registry preserves our history through recorded sound and reflects our nation’s diverse culture,” Hayden said. “The national library is proud to help ensure these recordings are preserved for generations to come, and we welcome the public’s input on what songs, speeches, podcasts or recorded sounds we should preserve next. We received more than 1,100 public nominations this year for recordings to add to the registry.”

A 1994 promotional still from the release of “All I Want For Christmas Is You.”

A 1994 promotional still from the release of “All I Want For Christmas Is You.”“Christmas” is Carey’s first song to make the NRR and she was delighted with the news. She cowrote the song in 1994 when she was just 22, thinking back on her often turbulent childhood years in Long Island and how she had always longed for Christmas to be a lovely holiday for the family. It rarely was, and she turned that longing into what is now a cultural touchstone.

“I tried to tap into my childhood self, my little girl self, and say, ‘What are all the things I wanted when I was a kid?’” she said. “I wanted it to be a love song because that’s kind of what people relate to, but also a Christmas song that made you feel happy.”

After working out a the lyrics and a melody line, she brought a demo tape to her then-songwriting partner and producer Walter Afanasieff, and the pair worked together to create its retro “wall of sound” production, as if it might have been a recorded in the 1960s. A modest success upon release, it’s grown to be a cottage industry unto itself. It has been featured in films, Carey wrote a children’s book based on it and filmed three different music videos. It’s hit No. 1 on pop charts each of the last four years, setting Carey’s pop-culture image as the Queen of Christmas.

“I’m most proud of the arrangements, the background vocal arrangements,” she said, describing the sessions with her supporting vocalists as one of the best experiences of her recording career.

“‘All I Want for Christmas…’ is sort of in its own little category,” she said, “and I’m very thankful for it.”

The recordings selected for the NRR bring the number of titles on the registry to 625, representing a minuscule portion of the national library’s vast recorded sound collection of nearly 4 million items.

This year’s selections features the voices of women whose recordings have helped define and redefine their genres. Madonna’s 1984 smash hit album “Like a Virgin” would fuel her ascent in the music world as she took greater control of her music and her image. Of the nine songs originally on the album, four became top 10 hits. Queen Latifah is the first female rapper to join the registry with her debut album “All Hail the Queen” from 1989 when she was just 19 years old. Her album showed rap could cross genres including reggae, hip-hop, house and jazz — while also opening opportunities for other female rappers.

Annie Lennox and Dave Stewart in their Eurythmics heyday. Photo: Eurythmics.

Annie Lennox and Dave Stewart in their Eurythmics heyday. Photo: Eurythmics.By the 1980s, Annie Lennox and Dave Stewart had been in and out of British-based music groups for some time without much success. Flat broke in 1982, Stewart managed to borrow enough money to buy a couple of synthesizers and a prototype of a drum machine so basic that it was housed in a wooden case.

One night in their studio — the loft of a picture-framing factory in central London — he got the drum kit going and hit a couple of chords on the synthesizer. Lennox sat up bolt upright, as if she’d touched an electric wire. She went to her own synthesizer, played a riff against his beat and soon ad-libbed a lyric, a wry, ironic comment on their impoverished status: “sweet dreams are made of this.”

“It’s a mantra, almost like a Haiku poem, a coded message, a commentary about the human condition,” Lennox said of the song. “You can use it as a happy birthday song or a celebratory song…it could be anything. Looking back, I love the way people have identified with it.”

With roots in Panama in the 1980s, reggaeton has been described as reggae, reggae en Español, dancehall, hip-hop and dembow. But it was Daddy Yankee’s 2004 hit single “Gasolina” that ignited a massive shift for reggaeton with its crossover appeal from Latin radio to broad audiences. “Gasolina” appeal was so great that it even moved some radio stations to switch formats from English to Spanish to tap into this revolution.

New Orleans jazz legend Wynton Marsalis explained that his “Black Codes (From the Underground)” album – recorded in 1985 when he was just 23 – was hard-swinging jazz that addressed the lingering societal effects of the Black Codes, the notorious post-Civil War laws that his native Louisiana and other Southern states used to keep black citizens in a violent state of oppression.

“A lot of 20th century civil rights cases were based on the Black Codes, on laws that tried to politically undress the achievements of the Civil War,” he said in an interview. The “From the Underground” part of the title refers to Black resistance to those laws: “No matter how defeated things seem, there’s always an idea in the pursuit of freedom that is subversive to anti-democratic thinking. I was very conscious of that (when recording).”

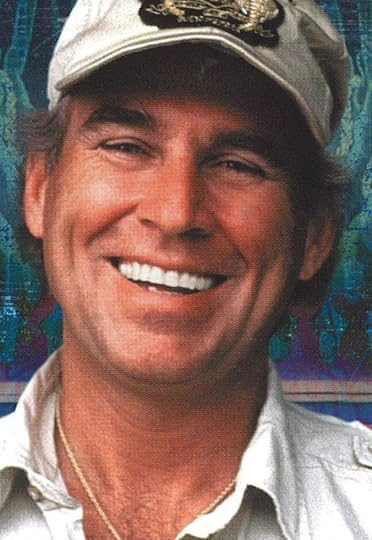

Photo courtesy of Jimmy Buffett.

Photo courtesy of Jimmy Buffett.And finally, for everyone who has been near a beach in the past four decades, “Margaritaville.”

It’s hard to believe now, but early in the 1970s Jimmy Buffett was a little-know singer/songwriter who had one modest hit, “Come Monday.”

But, hanging out in Austin, Texas, with friends Jerry Jeff Walker and Willie Nelson, he had a long night on the town. The next afternoon, he he had a tasty Margarita at a bar. Still sipping, he started scribbling a song on a cocktail napkin, finished it later while stuck in a traffic jam on the Seven Mile Bridge in the Florida Keys and played “Margaritaville” for the first time in a little bar in Key West that night when it was “probably six hours old.”

People liked it and he routinely played it during his live concerts for a couple of years. When he finally recorded it in 1977, it was an instant Top 10 hit and has since become a pop culture staple. Buffett, a working-class kid from the Mississippi Gulf Coast, was appalled by the standard music contracts of the time that did not let songwriters keep the publishing rights to their works, so he was always attuned to making money on his tours and selling merchandise to fans as a means of more lucrative income.

Over time, this entrepreneurship with his biggest hit morphed into an astonishing array of “Margaritaville” themed businesses and products — now including bestselling books, a popular chain of restaurants, a radio channel, a cruise line and 55-and-older living communities. His tours are still wildly popular, too.

The key to the song’s resonance in American culture, Buffett told the Library, was that people were looking for a song to make them feel good and be happy.

“You’re lucky enough at some point to put your thumb on the pulse of something that people can connect with,” he said. “It’s an amazing and lucky thing to happen to you, and that happened with ‘Margaritaville.’”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

April 4, 2023

Q & A: Michael Stratmoen

Michael Stratmoen is a program specialist for the John W. Kluge Center.

Tell us about your background.

I am a Washington, D.C., area local. I was born in Columbia Hospital for Women (since converted into a condo complex), near Dupont and Washington circles in D.C. My parents met when they worked for the Department of Agriculture in the 1970s, and they raised me in Herndon, Virginia. My mother still lives in the house I grew up in.

I went to Bishop O’Connell High School in Arlington, Virginia. From there, I went to James Madison University, then George Mason University for graduate school. I have bachelor’s and master’s degrees in public, or applied, history — history degrees with an emphasis on fields such as museum studies, archival studies, archaeology and historic preservation.

While studying, I worked at university libraries to support myself. I had jobs in special collections at James Madison University’s Carrier Library and as a graduate assistant in George Mason University’s library system. Then, I worked in the Access Services Division at Georgetown University’s Lauinger Library.

Initially, I hoped to use my degree in a museum setting. But I found myself building a pretty strong library resume with my employment record.

What brought you to the Library, and what do you do?

My first job at the Library was in the Copyright Office. I began in 2010, shortly after my 25th birthday, and worked for seven years as a materials expediter with a couple stints in the office’s registration and recordation programs.

In 2018, I joined the Kluge Center’s staff. My work in libraries and my degrees in public history have really come together in my current position as a program specialist.

I help run the Kluge Center’s fellowship and internship programs and events for members of Congress, congressional staff and the public. Each year, the center brings about 100 scholars from around the world to research in the Library’s collections and offers many excellent associated events.

I feel as if the work I do helps scholars perform cutting-edge humanities research and helps the Library call attention to their work. It is very fulfilling. No two days are alike, and I am constantly learning and getting to know an array of interesting scholars.

I’ve also been able to develop relationships with staff members from all over the Library. That has given me a much bigger understanding of the scope of activity that happens here at the world’s largest Library.

What are some of your standout projects?

When the Kluge Center needed a new application portal for our in-house fellowship programs, I was put in charge of the process. It took some time, but we now have a great system that we are using for the third year.

I also took a leading role in working with scholars who were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. That involved rescheduling scholars who could not come during the pandemic or who had to leave and return because of it — not to mention scheduling scholars who received placements for 2022. Most of the affected scholars have now been accommodated, and I am thrilled to have made it work for them.

I’ve also been heavily involved in several event series for members of Congress and senior staff. It feels like a great accomplishment to see members and congressional staff enjoy themselves; we try our best to nurture bipartisanship and collegiality, and I believe we are doing good work in this regard.

What do you enjoy doing outside work?

I love to travel with my husband. Last year, we went to Montreal, Rome, Split (in Croatia) and Istanbul. This year, we plan to go to Portugal and Costa Rica.

We also spend a great deal of time with our friends in Bethesda, Maryland, where we live. We frequently allow our 3-year-old nephew to ransack our apartment.

What is something your co-workers may not know about you?

I am big into cycling. Friends and I have been training to do the entirety of the C&O canal towpath from Cumberland, Maryland, to Georgetown. This October, we may finally make it happen!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 30, 2023

Baseball Opening Day, and the Library Adds MLB History Online

The following guest post was written by Peter Armenti and Darren Jones, research specialists in the Library’s Researcher and Reference Services Division.

Buy me some peanuts and Cracker Jack — it’s Major League Baseball’s Opening Day!

To celebrate the start of the 2023 season, the Library is pleased to announce a new digital collection: Early Baseball Publications. The collection, which will grow over time, provides full-text digitized access to more than 120 early baseball publications.

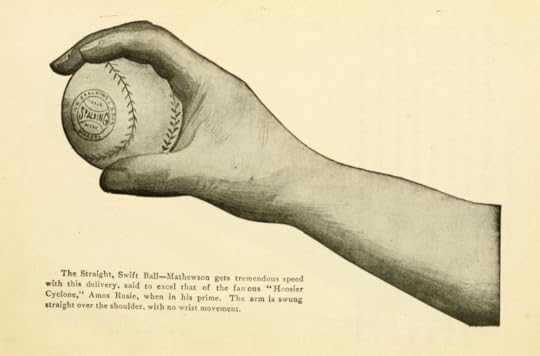

The initial release includes a large selection of 19th- and early 20th-century annual baseball guides, including many volumes of Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide, one of the premier baseball publications of its day. Also included are rule books, record books, scorekeeping guides and books on how to hit and play different positions.

Early Baseball Publications updates and expands the Library’s long-standing Spalding Baseball Guides digital collection, which will be retired in several months once its content has fully migrated to the new collection. The new collection will include the 15 Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guides published between 1889 and 1939 in the legacy collection as well as the 20 Official Indoor Base Ball Guides also found there (“indoor baseball” developed into what we know today as softball).

Many of the more than 120 publications in the new collection were published by Albert Spalding’s American Sports Publishing Company. Among these are not only the annual Spalding guides, but also a number of rule books and instruction manuals. The 1911 manual How to Pitch, for instance, provides detailed illustrations showing how to grip the ball to throw different pitches, such as the “straight, swift ball” (fastball) thrown by New York Giants ace and future Hall of Famer Christy Mathewson:

“The Straight, Swift Ball.” Illustration from “How to Pitch.” American Sports Publishing Company, 1911.

“The Straight, Swift Ball.” Illustration from “How to Pitch.” American Sports Publishing Company, 1911..The collection also includes a number of unexpected finds, such as The Orr-Edwards Code for Reporting Base Ball, an 1890 instruction manual for sports journalists covering the game. It focused on shorthand to use on the telegraph.

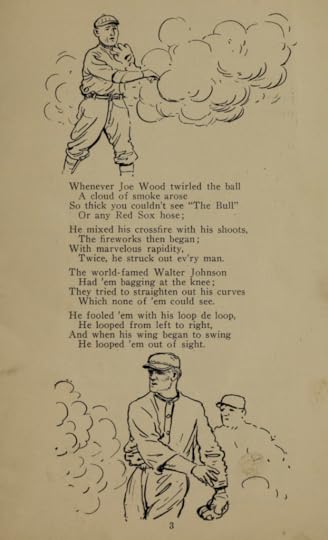

While the collection is focused on works of nonfiction, one poetic surprise we discovered was “Chick Gandil’s Great Hit” from 1914. Written by Gilbert Marquardt Eiseman, the poem adapts “Casey at the Bat” by imagining a tense game between the Washington Senators and Boston Red Sox. The hero is Washington first baseman Gandil, whose talent would be overshadowed several years later by his involvement as the ringleader of the 1919 Chicago “Black Sox” game-fixing scandal, for which he and eight other players were permanently banned from baseball.

First page of “Chick Gandil’s Great Hit.” Judd & Detweiler, Inc. c1914.

First page of “Chick Gandil’s Great Hit.” Judd & Detweiler, Inc. c1914.Early Baseball Publications represents only a fraction of the baseball materials at the Library. You can learn more about our extensive baseball holdings — among the largest in the world — and many other baseball materials by exploring our online Baseball Resources at the Library of Congress.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 28, 2023

Mark Dimunation, Master of Rare Books and Excellent Anecdotes, Retires

It’s difficult to say if Mark Dimunation is better at curating rare books or telling stories about them. Probably not possible to make the call, actually.

He’s displayed both abilities in person, in print, onstage and on television since he was appointed chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library — the largest collection of rare books in North America — a quarter of a century ago, in 1998.

And both were on display for a final time last week during an open house displaying some of the sparkling finds the division has acquired under his tenure. Dimunation, 70, who is retiring this week, was seated at the front of the Rare Book reading room, greeting a stream of well-wishers from across the Library and the antiquarian community.

“Starting at the LOC and buying books was a little bit daunting, because there’s a million books here,” he said, referring to the section’s holdings. “We cover everything from cuneiform tablets and medieval manuscripts all the way up to the 21st century. So, what do you buy in your first week is a very good question.”

One of the answers: “The Word Returned,” a 1996 artist book by Ken Campbell, the famed British printer who passed away last year. Campbell became regarded as one of the most influential book artists of the century, and the Library is one of the few institutions in the world with a complete run of his works.

Spread across the reading room — classical architecture, high ceilings, a chandelier, study tables set with small lamps, the room filled with murmurs and conversations — were more than 100 other books and printed material gathered in Dimunation’s tenure, showcasing the Library’s sweep of culture and history.

On this table, a first edition of Galileo’s “Starry Messenger,” published in 1610, the key work by the world-changing Italian astronomer, acquired by the Library in 2008. Here’s a flavor of Dimunation’s narrative style, explaining the book’s significance at a forum with the Librarian of Congress, Carla Hayden: “At dusk on November 30, 1609, Galileo shifted his telescope in the direction of the moon …”

There, that’s it, the Dimunation Anecdote: A startlingly specific scene, a famed personality at the moment of discovery … and, voila, centuries later, the very book, in the creator’s hand, right in front of you.

Another delightful acquisition lies on a nearby table: A first edition of Edward Gorey’s charmingly sinister “The Gashlycrumb Tinies,” a 1963 series of dark pen-and-ink sketches that walked readers through the alphabet by means of soon-to-be deceased children. The book is open to one of its most famous pages: “N is for Neville who died of Ennui.” The book’s page, part of a Gorey collection acquired in 2014, showed hapless little Neville, only his black-dot eyes and top of his head visible above the windowsill, gazing at a world of gray. It’s sad and funny and strange and surreal all at once.

In between, and spread across the hall to the Rosenwald reading room, were a constellation of books and papers from across the centuries, including 19th-century children’s books that doubled as pop-up theaters, the 20th-century Harlem Renaissance and art books made of almost everything, including leather and steel. Joan Miró’s 32-foot-long scroll, “Makemono” was there, but only partially unrolled.

Dimunation, a Minnesota native, grew up in a Ukrainian household, imbued with the culture of his immigrant grandparents. He was fascinated with maps, history and the larger world.

After getting his master’s degree in history from the University of California, Berkeley, his professional niche became 18th- and 19th-century English and American printing. He came to the Library from Cornell University.

Since then, he’s often been one of the more public faces of the Library. He’s taught seminars at the Rare Book School, appeared on several of the episodes of the History Channel’s “Hidden Treasures at the Library of Congress,” delivered dozens of lectures at museums and book events and written for publication often, including this blog.

He has also hosted dozens, if not hundreds, of show-and-tell events for Library guests. When actor, magician and author Neil Patrick Harris appeared at a 2019 National Book Festival Presents event, Dimunation wowed him by presenting a copy of some of the Library’s Houdini collection.

Other prominent guests visited in more low-key settings. At the open house, he regaled a small crowd with the story of the time Irish actor Pierce Brosnan came through the division. Dimunation, knowing his audience, set out a rare copy of “Ulysses,” by fellow Irishman James Joyce, at a side table. Brosnan instantly recognized the copy in its rare blue cover and, transfixed, asked to see it.

The one-time James Bond star paged through it for a moment and, without looking up, “suddenly starts reading in this Irish brogue,” Dimunation recounted. “We’re sitting there for a good 10 minutes, while he read Joyce, and you’re just transfixed.”

It’s those kind of moments, Dimunation said, that makes the Library an endlessly fascinating place. You never know who, or what, you’ll find.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 24, 2023

My Job: Carol Lynn Ward Bamford and the Flute Vault

Carol Lynn Ward Bamford curates collections of musical instruments.

Describe your work at the Library.

I take care of the musical instruments collections in the Music Division. The Library has over 2,000 instruments — mostly woodwinds and bowed stringed instruments — that are available for study, performance and exhibition.

My days are spent managing their care; their use in public performances, displays and exhibitions; and visitor requests to see, examine or copy them. The Dayton C. Miller flute collection comprises not just the flutes themselves but also an entire reference collection of related books, music scores, patents, iconography, statues, photographs and more. So, I often work with different divisions at the Library and many types of visitors!

How did you prepare for your background?

I went through graduate school in music and performance on the flute. I taught flute, freelanced, played with an orchestra and worked in a flute manufactory. One day, literally, I just felt I had accomplished all I wanted to do on the flute. After considering further studies in musicology, I decided instead to be a librarian.

Off I went to library school at Simmons University. Next door was the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. I started work there in the musical instruments department, and that was that! I knew I was in the right place. At the same time, I took a publishing class at Simmons. For my final project, I created a catalog of the Miller flute collection and was told to show it to the Library’s Music Division. So, I did!

I applied for a temporary job here at the Library and got hired for 120 days. That was good enough for me. I eventually got a permanent job here and turned that final school project into the Library’s Dayton C. Miller website.

I feel that working here with researchers, visitors, the public and our staff and fielding all their questions that I am at work on a Ph.D. in “how to answer”!

What have been your most memorable experiences at the Library?

Before the visit of singer-songwriter Lizzo to the Library’s flute collection: getting my first thank you note. It was from a young girl, filled with her words and drawings of flutes. I have it in my office, where I see it every day. I was so grateful she sent it because that made me realize we can have an impact, no matter what the age of the visitor.

Also before Lizzo: the power of collaborating with other divisions and institutions. I worked as part of a team with the Library’s Preservation Research and Testing Division, Catholic University and George Washington University studying our glass flutes via a three-year major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Then there was the visit to the Library by Lizzo and the concert at Capital One Arena the next day at which she played our Madison flute onstage. While that event was one of the hardest days of my Library life, it also was one of the best. It had great impact on the Library and the flute in general.

And everyday memories: the power of donors and their generosity.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 20, 2023

Fabulous Flutes

Call it the flute heard ’round the world.

Standing in the Great Hall last fall, Grammy-winning singer-songwriter Lizzo gave an impromptu performance on one of the Library’s most-prized musical instruments: a rare crystal flute that once belonged to President James Madison.

The next night, she and the flute reprised the performance at her Capital One Arena concert before thousands of adoring fans, holding their phones aloft to record the scene for posterity and TikTok.

“I want everybody to make some noise for James Madison’s crystal flute, y’all,” said Lizzo, who then advised the crowd about the difficulties of playing such an unusual instrument: “It’s crystal — it’s like playing out of a wine glass!”

The combination of Lizzo and Madison set social media afire: A behind-the-scenes video of her Library visit drew record (for the institution) views — nearly 7 million on the Library’s main Twitter, Facebook and Instagram accounts. The concert performance likewise drew millions of views elsewhere in the social media universe and coverage from dozens of media outlets.

The instrument that helped set off the bedlam is the most prominent piece in a collection donated to the Library in 1941 by physicist, astronomer and major flute aficionado Dayton C. Miller. The collection is not just the world’s largest of flute-related material, it is perhaps the largest collection on a single music subject ever assembled — and it’s what drew Lizzo to the Library in the first place.

The Miller collection contains nearly 1,700 woodwind instruments spanning five centuries; over 10,000 pieces of sheet music and 3,000 books; some 700 prints, etchings and lithographs; more than 2,500 photographs; scores of bronze statues and porcelain and ivory figurines; plus patents, trade catalogs, news clips, correspondence and autographs.

Plexiglass flute in C with chromium plated fittings, produced by Markneukirchen in 1937, Dayton C. Miller Collection/Music Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Plexiglass flute in C with chromium plated fittings, produced by Markneukirchen in 1937, Dayton C. Miller Collection/Music Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.The flutes cover an enormous range of cultures, materials, shapes and sizes. Collectively, they tell the story of the history of the flute. Many of the individual instruments have their own stories.

The crystal flute played by Lizzo was created in 1813 years ago by French maker Claude Laurent and presented to President Madison on the occasion of his second inauguration —a silver joint on the instrument is engraved, in French, with Madison’s name and title. It’s believed that Madison’s wife, Dolley, rescued the flute from the White House when the British burned the capital during the War of 1812.

Another flute, stored in a plush porcelain casket, once belonged to 18th-century Prussian monarch Frederick the Great, one of history’s most famous amateur musicians. Frederick maintained an excellent court orchestra and composed music for it himself; the Miller collection includes not only the king’s flute but original music manuscripts of his compositions.

There are instruments made of gold, silver, glass, jade, tortoiseshell, boxwood, bamboo, ivory, bone and cocus, a West Indian tree that furnishes a fine green ebony. Some take most-unlikely forms: a gavel, walking sticks, birds, a four-legged mammal and what appears to be a horned toad climbing a tree.

They span continents and cultures: xaios from China and flageolets from England, Egyptian zummāras, Bulgarian kavals, Japanese shinobues, Chippewa moose calls, northern Italian panpipes and a Cheyenne courting flute decorated with a stag’s head and the sun and moon.

The flute that inspired Miller’s interest — listed as item No. 1 in his ledger — is a fragment of a humble rosewood fife his father played in the Union Army during the Civil War.

The collection reflects the man who created it more than a century ago — Miller possessed a deep and practical mind and an inquisitive nature. Even given his passion for music and an artistic bent, he remained a scientist first.

“A comprehensive appreciation of the art of the flute requires, besides a knowledge of music in general, also a knowledge of the physical principles of the flute as a sound producing instrument, of the mechanical devices by which these principles are used …” he wrote in his treatise, “The Flute.”

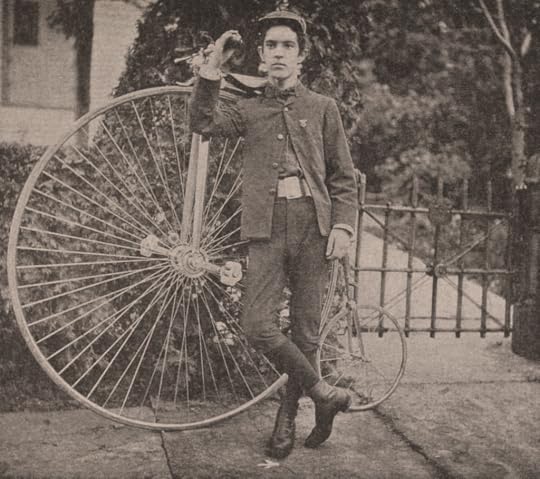

Dayton Miller at 17 with a bicycle, about 1883. Photo: Unknown. Music Division.

Dayton Miller at 17 with a bicycle, about 1883. Photo: Unknown. Music Division.Miller grew up in a small Ohio town, obsessed with science and music — at his graduation from Baldwin College, he delivered a lecture about the sun and, as part of the ceremony, played a Beethoven piano concerto on the flute.

He earned a Ph.D. in astronomy from Princeton and taught physics at the Case School of Applied Science in Cleveland for a half-century. He debated Albert Einstein about ether drift theory and hosted him at his home — Einstein signed the Miller guest book.

Miller pioneered the use of X-rays in medicine. In 1896, he learned of the discovery of X-rays by a German scientist, promptly built his own apparatus and began experiments. He made a composite, full-length X-ray of his own body. He photographed a boy’s broken arm and produced what perhaps was the first X-ray used for surgery in America. He delivered more than 70 lectures around the U.S., promoting the use of the X-ray.

He became an expert on acoustics and invented the phonodeik, a device that converted sound waves into visual images — among other uses, he employed the machine to compare waves produced by flutes made from different materials. During World War I, Miller studied the pressure waves caused by the firing of large guns, providing material for medical investigations of shell shock.

Armed with a passion for music and a knowledge of the physics of sound, Miller also became one of the world’s foremost experts on the flute. He developed into an excellent amateur player. By the 1890s, he was a serious collector of all things flute: instruments, books, scores, images, statues, you name it.

He also came along at the right time: Few other serious collectors were around to compete for prize pieces, making the market affordable.

The Miller collection contains, for example, 18 crystal flutes from the early 19th-century Paris workshop of Laurent. In 1923, Miller paid $200 (about $3,500 in today’s dollars) for the Madison flute — an incredible bargain for an instrument that is both of a rare type and, by its association with the president, an irreplaceable, one-of-a-kind historical object. In 1940, he bought an 1815 Laurent glass flute from the British firm Rudall Carte for 10 pounds (about $40 at the time, according his ledger, and around $850 today).

Interior view of a 1937 Gebrüder Mönnig plexiglass flute in C with chromium plated fittings, produced by Markneukirchen. Photo: Shawn Miller. Music Division.

Interior view of a 1937 Gebrüder Mönnig plexiglass flute in C with chromium plated fittings, produced by Markneukirchen. Photo: Shawn Miller. Music Division.Given his nature, Miller wouldn’t be content to merely collect.

He composed music for the flute: Two pieces, “A Lover’s Prayer” and “The Audacious Jewel,” were dedicated to his wife, Edith Easton. He built several of his own instruments — he had learned to make things in the tin shop at the rear of his dad’s hardware store in Berea, Ohio.

In 1901, he built a flute of silver at a cost of $44 in material and special tools. He once played a gold flute in London and thought it the finest instrument he’d ever played. So, he built his own. Miller kept an elaborate log of each procedure and the time required to complete it — the entire process took over 3-1/2 years. The finished flute featured a tube of 22-karat gold and a mechanism of 18-karat gold and included fingering and tuning features not incorporated together on any other instrument.

He was such an expert that flutemakers from around the globe traveled to him to consult on manufacturing their instruments, to gain insight from his personal knowledge and from the collection he had amassed.

Today, 82 years after Miller’s death, folks still do, in a way.

Researchers and musicians, like Lizzo, from around the world still come to the Library, to see and to study the greatest flute collection ever assembled.

—Mark Hartsell is editor of the Library of Congress Magazine. This article appears in the March/April 2023 issue.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers