Library of Congress's Blog, page 23

June 16, 2023

Bloomsday! The Library’s One-of-a-Kind Copy of “Ulysses”

James Joyce in 1915. Photo: Alex Ehrenzweig. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

James Joyce in 1915. Photo: Alex Ehrenzweig. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.It’s Bloomsday, the annual celebration of James Joyce’s landmark modernist masterpiece, “Ulysses.” Published 101 years ago, Joyce’s book famously examines one day — June 16, 1904 — in the life of Leopold Bloom of Dublin, Ireland. The book’s stream-of-consciousness style and dense symbolism have made it a cult favorite to fans around the world, who celebrate today with readings, festivals, dressing in period costumes and, if possible, wandering around Dublin themselves. Pubs do bang-up business.

Across the Atlantic, the Library has some of the most extraordinary copies of the book ever printed. But first, a quick recap:

Paris, 1922: Sylvia Beach, proprietor of Shakespeare and Company, the famous bookshop, decides to publish “Ulysses.” This is risky because pre-publication excerpts had been declared obscene by U.S. courts.

Beach limited her first edition to 1,000 copies. All were numbered, and 100 were signed by Joyce. It was a brilliant decision. The novel went on to be regarded as one of the premier literary works of the 20th century and Joyce one of the era’s great authors. Copies of that first print run became some of the most sought-after books of the age. (A first edition famously sold at auction in London in 2009 for the equivalent today of of $636,000; signed and personal copies have sold for much more.)

The bespoke calfskin cover of the LIbrary’s edition of “Ulysses.” Photo: Shawn Miller.

The bespoke calfskin cover of the LIbrary’s edition of “Ulysses.” Photo: Shawn Miller.And yet all of that scarcely begins to describe the first edition of “Ulysses” acquired in 2021 by the Library. It’s a marvel to behold: Copy #361 is bound in bespoke calfskin, front and back covers initialed by the author, the title page inscribed by Joyce to a friend, with inserts that include Joyce’s guide to deciphering the book.

Two other “Ulysses” first editions were included in the acquisition of the Aramont Library (the property of a private owner), including the signed #1 copy — the first copy of the first edition, an almost unbelievable find of such an important book.

“All of these copies are exceptional, but there is one that is truly unique,” said Stephanie Stillo of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, indicating the custom-made copy.

Joyce, a native of Ireland, spent years laboring over the complicated novel while living in Europe. It’s modeled on Homer’s epic poem “The Odyssey,” told in 18 chapters in almost bewildering fashion. One sentence runs 4,391 words. As the British Library sums it up “… each episode is represented by a different organ of the body, colour, symbol, technique, art, place and particular time of day.”

Beach, a friend of many modernist artists, published the first copies on Feb. 2, 1922, Joyce’s 40th birthday.

While finishing the book, Joyce befriended a young French admirer, Jacques Benoist-Méchin. Just 20 years old, Benoist-Méchin was a promising intellectual who helped Joyce finalize the book’s famous last sentences, a soliloquy by the fictional Molly Bloom.

They apparently worked together to make #361 an unforgettable copy. Joyce inscribed the copy to him. A sketch map of Dublin adorned the front, as it was the book’s setting. The back cover was a map of Gibraltar. This was a nod to Benoist-Méchin’s help in interpreting Molly’s famous closing scene; in the book, she is born in Gibraltar.

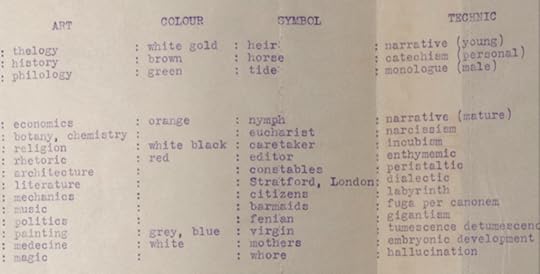

Detail of Joyce’s explanation of the book’s themes and symbols. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Detail of Joyce’s explanation of the book’s themes and symbols. Photo: Shawn Miller.But the real gems were at the back.

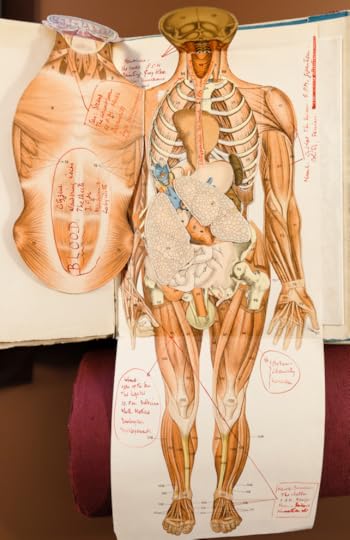

A four-page scheme, or outline, explains the book’s convoluted plot and its symbolism, including Joyce’s notation that the book was based on “The Odyssey,” without which the world might never have noticed the connection. (Only seven of these outlines are known to exist.) Then, another stunner — a full-color foldout anatomical chart of a human body, likely taken from a medical textbook, annotated in red ink, noting how each body part relates to the plot.

Tucked inside the back cover is this drawing of a human body, with notes showing how various body parts correspond to different chapters. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Tucked inside the back cover is this drawing of a human body, with notes showing how various body parts correspond to different chapters. Photo: Shawn Miller.Finally, tucked inside this copy are portraits of Joyce (likely taken by famed photographer Man Ray) and Beach. There’s also a letter from Joyce to Benoist-Méchin.

The final twist: Benoist-Méchin grew into a prominence of his own as a historian and journalist who enthusiastically collaborated with Nazi Germany’s takeover of France in World War II. He was condemned to death as a traitor after the war and eventually had his sentence commuted after seven years in prison.

All of that 20th-century history, bound in one completely original book. It’s something to behold.

The rear cover of the book features this map of Gibraltar. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The rear cover of the book features this map of Gibraltar. Photo: Shawn Miller.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 15, 2023

Ralph Ellison’s “Juneteenth” Lives on at the Library

—This is a guest post by Barbara Bair, a historian in the Manuscript Division. It appears in the May-June issue of the Liibrary of Congress Magazine.

The nation will pause for a national holiday on Monday to mark Juneteenth, the anniversary of the day when enslaved people in Texas finally heard the news of emancipation at the end of the Civil War. The Library preserves the history of that day in many ways, including Ralph Ellison’s delirium-dream of a second novel, “Juneteenth,” in which he took a deep dive into the complexities of race and violence and the costs of transformation in America.

The novel, like the struggle for equality and justice itself, was a long time in the making — a wrestling with the self and a perpetual work in progress. Ellison began to formulate the book in thoughts and notes in the 1950s, during the era of Brown v. Board of Education and the 1952 publication of his masterpiece, “Invisible Man.” But its genesis was longer, stemming from Ellison’s difficult childhood and the world he witnessed around him in his youth and as a student at Tuskegee Institute.

Ellison died in 1994, leaving behind over 2,000 pages of drafts and notes and revised episodes and passages for what he thought might be one book, or maybe three. All are now in the Ralph Ellison Papers at the Library.

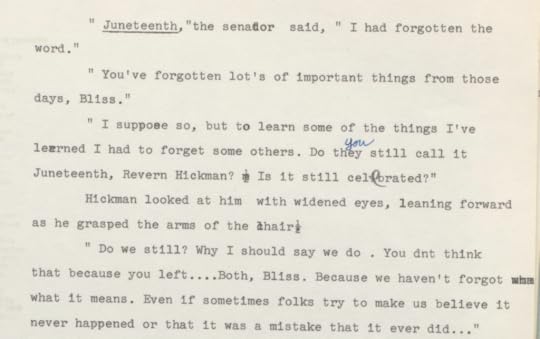

A manuscript page from “Juneteenth,” with handwritten notations. Manuscript Division.

A manuscript page from “Juneteenth,” with handwritten notations. Manuscript Division.With the blessings of his widow, Fanny Ellison, the Manuscript Division preserved and organized the papers and Ellison’s literary executor, John F. Callahan, crafted his words into the posthumous version of the novel as it is known by readers today. Callahan and Adam Bradley produced a revised version under the title “Three Days Before the Shooting …” in 2010.

“Juneteenth” is deeply rooted in historic struggle across time. It is titled for a day of revelation, also known as Freedom Day, June 19, 1865.

While the jubilation of Juneteenth was real and the day remains a holiday of celebration and independence, it also signifies — like Ellison’s unfinished, morphing, questioning novel — that the full work of freedom is longstanding and intergenerational and that the forces of chaos and human failures are strong.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 9, 2023

The Ketubah, An Ornate Jewish Marriage Tradition

This is a guest post by Maria Peña, a writer-editor in the Office of Communications. This article also appears in the May-June issue of the LIbrary of Congress Magazine.

No Jewish marriage is complete without a ketubah (plural, ketubot), a traditional legal document introduced during the wedding ceremony. The ketubah not only legitimizes the marriage but, following Jewish law, also spells out the groom’s financial and conjugal obligations to his bride during their life journey.

Most traditional ketubot are written in Hebrew and Aramaic, and their artistry reflects the time, place and culture of their creation. The earliest surviving ketubah, found in Egypt and written in Aramaic on papyrus, dates from circa 440 B.C.

The earliest illustrated ketubot, however, originated in Venice and date to the late 16th and early 17th centuries. There, some Jewish communities began decorating ketubot with lavish colors, symbols and designs — arches, columns, decorated borders, human figures and motifs inspired by nature.

Some documents, like those produced in certain Italian cities such as Ancona, included an additional financial agreement between families written beneath the standard text, a practice that faded with time. The traditional ketubah described the groom’s contractual protections for his wife and, much like a contemporary prenuptial agreement, his financial obligations to her in case of divorce or widowhood.

The Library holds 11 traditional ketubot. An 1805 ketubah from Ancona, a center of ketubah production from the 17th to the 19th centuries, is decorated with human figures. One produced 70 years later in Tetuan, Morocco, displays only nature motifs — ketubot from Islamic lands weren’t decorated with human figures, instead drawing their richness from bright plant and animal motifs.

The oldest ketubah at the Library dates to 1722, from Ancona. Written in Hebrew and Aramaic and ringed by an elaborate network of colorful flowers and birds, the document records the marriage of Diamanti, daughter of Moses ben Raphael Ha-Cohen, to Samuel ben Moses, son of David Ha-Cohen. Text at the bottom describes valuables the bride brought into the marriage and other financial arrangements agreed upon by both families.

Modern-day Jewish marriage contracts remain as ornate and personalized as wallets will allow — with some including commissioned art, silver or gold leaf, and they become family heirlooms and lifelong treasures.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 7, 2023

My Job: Megan Metcalf & LGBTQ+ at the Library

Megan Metcalf is the collection specialist and recommending officer for LGBTQ+ studies and women’s and gender studies for the general and international collections. She’s also a reference librarian in the Newspaper and Current Periodical Reading Room. This article also appears in the May-June issue of the LIbrary of Congress Magazine.

Describe your work at the Library.

A typical workday usually involves a combination of assisting researchers, working on collection development and planning or producing outreach. Librarians assist researchers in person at the Library and remotely via our Ask a Librarian service and online programming.

Outreach is a very big part of what I do. I produce events and experiences, including research talks and panels, online presentations, tours and research orientations, hands-on workshops and more. I enjoy any opportunity to share our wonderful collections, especially as part of an exhibit or pop-up display. I also regularly write for Library blogs and social media, which is a great way to raise awareness and increase engagement.

When I work on collection development, I seek out materials in a variety of formats and languages to add to the collections. In 2020, we published the first collections policy statements for LGBTQ+ studies and women’s and gender studies at the Library. This helps to further define the scope of collecting efforts in these subjects. I also create resources for researchers, which includes curating five web archive collections and several research guides.

How did you prepare for your position?

I started working in bookstores as a teenager and got my first library job as an undergrad. I earned bachelors and master’s degrees in women’s and gender studies and a master’s in library and information science from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. During my time at UWM, I worked and taught in the women’s and gender studies department as well as the university library. When I finished graduate school, I worked as the instructional design librarian and women’s, gender and LGBTQ+ studies subject specialist for the UWM libraries until I moved to Washington, D.C., in August 2015.

What are your favorite collection items?

The Library has an impressive selection of LGBTQ+ periodicals, from the mid-20th century to present day. This includes rare early titles like The Ladder, The Mattachine Review and One magazine. Periodicals and other self-published materials provide a record of LGBTQ+ voices that otherwise wouldn’t have been preserved. It’s incredibly moving to realize that when these early magazines were published, people could have been arrested just for carrying them or sending them through the mail. Nothing moves me more than self-published materials.

What have been your most memorable experiences at the Library?

Getting to show the “Queer Eye” cast around the Library and collections in 2019 was such a thrill! In general, I love the possibility for serendipity that seems to live around every corner. Recently, I was giving a tour for LGBTQ+ historian Eric Cervini, and we just happened to run into “Atonement” author Ian McEwan with the Library’s literary director, Clay Smith. Our tours joined together for a short while, and it was so delightful and unexpected. Almost as unexpected as the time I ran into a live penguin in the Main Reading Room on World Penguin Day.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 30, 2023

Kluge Scholar George Chauncey on Libraries and LGBTQ+ History

This is a guest post by George Chauncey, the DeWitt Clinton professor of history at Columbia University and the 2022 recipient of the Library’s John W. Kluge Prize for Achievement in the Study of Humanity. It also appears in the Library of Congress Magazine.

For a long time, most people thought LGBTQ+ people had no history before Stonewall and the rise of the gay liberation movement in the late 1960s. Or that if there were a longer history, it consisted only of the police repressing isolated people who hid themselves in fear and shame.

When I began the research for my book “Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940,” I knew there had to be more to the story than this. But I didn’t know what I’d find. Or where I’d find it.

So, I headed to my local library, one of the great research libraries of the world, the magnificent, marble-clad New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue at 42nd Street, and spent months in its reading room poring over old manuscripts, organizational records, newspapers and photographs.

“Gay New York,” George Chauncey’s landmark book, built on library research.

“Gay New York,” George Chauncey’s landmark book, built on library research.It quickly became clear that the records of so-called “anti-vice societies” would be among my richest sources. From 1905 to 1932, one society dispatched secret investigators across the city to inspect saloons, speakeasies, dance halls and tenements they suspected of harboring vice. They were primarily looking for female prostitution, but along the way they periodically stumbled across what they called “perversion.” I read 10,000 of their typewritten reports to find about 200 reports concerning LGBTQ+ life. The world those reports revealed was astounding.

At a Brooklyn dance hall in 1912, an investigator observed two “fairies,” known as Elsie and Daisy, partying with a group of young immigrant women, borrowing their powder puffs, singing bawdy songs and dancing together, much to the women’s delight.

In 1928, an investigator visited a Harlem tenement where 15 Black lesbians and gay men were enjoying themselves at what the hostess called a “freakish party.” “The men were dancing with one another,” he reported, “and the women were dancing with one another.” When he asked one guest if she was “a normal, regular girl,” she defiantly replied, “Everybody here is either a bull dagger or a f–, and I am here.”

That same year, other investigators attended a “Fairy Masquerade Ball” in a prominent Harlem ballroom, where they found “approximately 5,000 people, … men attired in women’s clothes, and vice versa.” It was “an annual affair,” they learned, “where the white and colored fairies assemble together with their friends,” along with “a certain respectable element who go there to see the sights.” The ball was so acclaimed that Harlem’s newspapers published flattering stories about it, with drawings depicting the most glamorous gowns.

Rather than cowering in fear, in other words, many LGBTQ+ people boldly claimed their right to live freely. Rather than despising them, many “straight” people celebrated them.

The investigators were shocked. So was I. Here was evidence that LGBTQ+ life was far more visible and accepted in early 20th-century Black and immigrant neighborhoods than I had imagined, despite the policing of the anti-vice societies. This was the story I told in “Gay New York.” I could only tell it because a library had recognized the importance of preserving boxes of yellowing typewritten reports — and countless other records — that one day would make it possible for us to see our history anew.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!May 22, 2023

A Civil War Story: Rebecca Pomroy, Lincoln’s Nurse

This is a guest post by Michelle Smiley, an assistant curator of photography in the Prints and Photographs Division. It appears in the May-June issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Chris Foard went to the Civil War collectors show in Nashville back in 2007, looking for artifacts that combined his two passions, a career as a registered nurse and a devoted pursuit of historical nursing research.

What he found was unexpected and important: a trove of material that sheds light on the sufferings of Abraham Lincoln and his family during the most trying years of his presidency — and the woman who helped them get through it.

Paging through a series of correspondence at the show, Foard discovered a handwritten letter on stationary bearing the Executive Mansion insignia and a vague connection to Lincoln.

Intrigued, he investigated further. The letters, it turned out, came from a collection of correspondence, photographs and personal artifacts related to the life of Rebecca Pomroy, who served as a private nurse for the Lincolns during a time when, in addition to facing the traumas of a bloody war, they had suffered a devastating personal loss.

The collection Foard discovered now resides in the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division, thanks to a recent donation by Civil War collector Tom Liljenquist. Lincoln’s papers are in the Manuscript Division.

Rebecca Pomroy. Photo: Brady’s National Photographic Portrait Galleries. Prints and Photographs Division.

Rebecca Pomroy. Photo: Brady’s National Photographic Portrait Galleries. Prints and Photographs Division.Pomroy, born in Boston in 1817, had tended to ailing family members as a young woman and, after she married at 19, to her husband suffering from chronic asthma. Over a five-year period, Pomroy’s husband, two of their children and her mother passed away.

The losses deeply wounded Pomroy. At a friend’s request, she attended a religious camp in Boston, where she experienced a “calling” to do God’s work. Inspired, by July 1861, she had responded to an advertisement in a local paper seeking nurses to tend to soldiers wounded in the recently begun war. By that September, she was in Washington, D.C., doing just that.

With the diversion of able-bodied men to the front lines, nursing presented a new professional arena for women. Pomroy believed they could make unique contributions: “There is so much that a woman can do,” she wrote,” that a man never thinks of.”

In February 1862, as the war raged, Lincoln and his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, lost their 11-year-old son Willie to typhoid fever, leaving the family in shambles. Their youngest, Tad, still was suffering from the disease. Mary was so distraught over the loss of another child — their son Eddie had died of tuberculosis 12 years earlier at age 3 — that she remained in bed for three weeks and didn’t attend Willie’s funeral.

Willie Lincoln shortly before his death. Photo: Mathew Brady. Prints and Photographs Division.

Willie Lincoln shortly before his death. Photo: Mathew Brady. Prints and Photographs Division.Fearing for his wife and child, Lincoln sought help. On the recommendation of Dorothea Dix, the superintendent of Army nurses, Pomroy was chosen to serve the Lincoln family. She did not, however, immediately jump at the invitation.

“Dorothea Dix meets with Rebecca Pomroy at Columbian College Hospital and tells her, ‘Pack your bags. We are going to the White House,’ ” Foard said. “But she did not want to go. She was really upset because she thought, ‘Oh, I don’t want to leave my boys.’ ”

Pomroy’s devotion to “my boys,” as she called the soldiers she tended to at the hospital in nearby Meridian Park, testifies to her deep commitment to human care.

Despite her reservations, Pomroy agreed to help the Lincolns, and her talents as a caregiver — and her own experiences of loss and grief — allowed her to grow close to the family. They confided in her. The president discussed the Emancipation Proclamation with her. He accompanied Pomroy on a carriage ride through town and made a special visit to Columbian Hospital, to the surprise and delight of the soldiers and staff.

Although hesitant to request anything in return, Pomroy asked Lincoln to award her only surviving son, George, a commission as second lieutenant in the Army. He obliged. As Pomroy later recounted, “When the President left me, he said he felt that he was still in my debt.”

Still, Pomroy’s inner conflicts lingered — she wanted to get back to the hospital but also to serve the Lincolns. So, Lincoln arranged for Pomroy to resume work at the hospital but still make frequent visits to the White House.

“I have seen the whole of the mansion, and all that pertains to it,” Pomroy wrote on April 23, 1862, “but let me be found sitting at the bed of the poor soldier, wetting his parched lips, closing the dying eyes, and wiping the cold sweat from his brow, rather than be in Mrs. Lincoln’s place with all her honors.”

The letters demonstrate a small sample of the ways in which the correspondence, photographs and artifacts — now part of the Library’s Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs — provide an unparalleled insight into Pomroy’s most intimate thoughts and experiences.

It was customary in the late 19th century for personal mementos to be made from hair. This is a cross made from Rebecca Pomroy’s tightly woven locks. Photo: Shawn Miller.

It was customary in the late 19th century for personal mementos to be made from hair. This is a cross made from Rebecca Pomroy’s tightly woven locks. Photo: Shawn Miller.The collection also includes personal objects — a cross made from Pomroy’s hair, a pair of earrings and an assortment of dried flowers picked from the White House garden — that enliven this seldom-told history of the Lincoln family’s private nurse.

“Pomroy deserves recognition given to other heroic women throughout history,” Foard said. “She was an admirable person not to be forgotten. I think that the Library of Congress will see that through.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 17, 2023

Paul Newman, Marilyn Monroe, Harry Belafonte: A Star-Studded Day at the Actors Studio

This is a guest post by Laura Kells, a senior archives specialist in the Manuscript Division. I t also appears in the Library of Congress Magazine.

Imagine all the talent in one room.

In 1951, actor, director and teacher Lee Strasberg became artistic director of the Actors Studio, an influential workshop that helped revolutionize the art of acting.

Over a quarter century, Strasberg drew an amazing assemblage of professional actors to the studio for classes in his system of “method acting,” or simply The Method. His pupils would bring a new, more realistic style of acting to stage and screen.

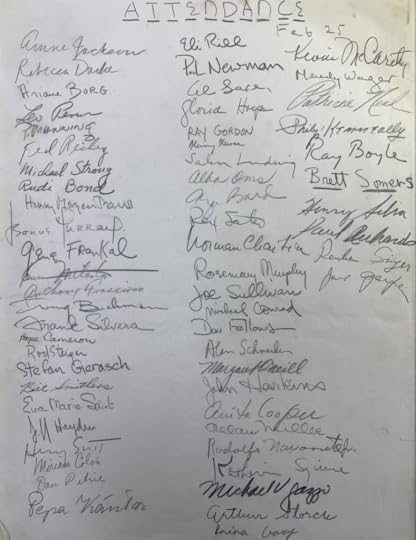

The Strasberg papers, held in the Manuscript Division, provide a unique glimpse inside the studio. Attendance sheets for 1952 to 1977 reveal which actors took part. Most are typed, alphabetized rosters of names. The sheets from 1955 are an exception: That year, attendees signed in on plain paper, usually in pencil.

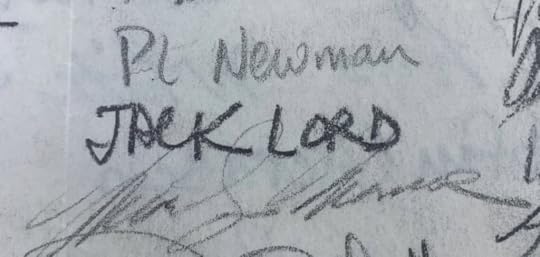

Paul Newman, Jack Lord (future star of “Hawaii Five-0”) and Marilyn Monroe consecutively signed into the Actors Studio one day in 1955. Manuscript Division.

Paul Newman, Jack Lord (future star of “Hawaii Five-0”) and Marilyn Monroe consecutively signed into the Actors Studio one day in 1955. Manuscript Division.The rosters reveal a galaxy of stars, in class honing their craft: Marilyn Monroe, Paul Newman, Harry Belafonte, Eva Marie Saint, Patricia Neal, Rod Steiger, Geraldine Page and Eli Wallach, among many others.

The pages offer signatures to analyze and connections to make: On April 29, Newman signed in boldly as P L Newman, followed soon after by Marilyn Monroe with a faint but distinctive signature. Also in class that day: television actor and director Leo Penn, who would raise one of modern cinema’s biggest stars — two-time Oscar winner Sean Penn.

Picture the scene: On Nov. 19, Martin Balsam signs in, followed immediately by Ben Gazzara, Monroe and Maureen Stapleton, who collectively would win nine Oscars, Tonys, Emmys and Golden Globes and earn 29 more nominations. Just a few spots ahead is Doris Roberts, who a half-century later would win four Emmys as the meddling mom on the TV’s “Everybody Loves Raymond.”

Presumably, the actors signed in and didn’t give it a second thought. But, today, those sheets are an invaluable resource for research into the history and influence of the Actors Studio — and intriguing artifacts for fans of movies, television and theater.

The sign-in sheet from the Actors Studio on Feb. 25, 1955. Manuscript Division.

The sign-in sheet from the Actors Studio on Feb. 25, 1955. Manuscript Division.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 10, 2023

Ada Limón Gets Second Term as Poet Laureate

Ada Limón, named the last year, will serve two more years, Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden has announced, making the California native the third laureate to serve for as long as three years.

Limón, the author of six poetry collections and winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry, is the nation’s 24th Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry, as the post is officially known. She began her her term in September 2022 and will conclude it in April 2025. She joins Joy Harjo and Robert Pinsky in serving for three years.

“During her first term, Ada Limón has done so much to broaden and promote poetry to reach new audiences,” Hayden said. “She also laid the groundwork for multiple laureate outreach efforts to come, many with federal agencies. A two-year second term gives the laureate and the Library the opportunity to realize these efforts and showcase how poems connect to, and make sense of, the world around us.”

On June 1, Limón will return to the Library to reveal a new poem she has written for NASA’s Europa Clipper mission. Limón’s poem will be engraved on the spacecraft that will travel 1.8 billion miles to explore Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons.

In August, she will appear at the National Book Festival. Later in the fall, the Library will announce details of Limón’s signature project — a first-ever partnership with the National Park Service and the Poetry Society of America to present poems in national parks across the country — as well as laureate initiatives with federal and nonfederal partners.

“I am beyond honored to serve for another two years as the poet laureate of the United States,” Limón said. “Everywhere I have traveled during my first term, both nationally and internationally, I’ve been reminded that poetry brings people together.”

During her first year, Limón participated in two events hosted by Dr. Jill Biden, first lady of the United States; one for the National Student Poets Program; and the other with Brigette Macron, wife of the president of France, during a state visit.

Limón also participated in an event hosted by Beatriz Gutiérrez Müller, wife of the president of Mexico, for the North American Leaders Summit in Mexico City. In Buenos Aires, Limón participated in a conversation with Argentine poets Laura Wittner and Daniela Auginsky for the Library’s Palabra Archive.

In April, for National Poetry Month, Limón served as the guest editor for the Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day series in a first-ever series collaboration between the academy and the Library.

Limón is the author of six poetry collections, including “The Carrying,” which won the National Book Critics Circle Award, and “Bright Dead Things,” a finalist for the National Book Award and the National Books Critics Circle Award. She is the recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center and the Kentucky Foundation for Women.

Her newest poetry collection, “The Hurting Kind,” was published as part of a three-book deal that includes publication of “Beast: An Anthology of Animal Poems,” featuring work by major poets over the past century, to be followed by a volume of new and selected poems.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 8, 2023

Researcher Story: Georges Adéagbo and Abraham Lincoln

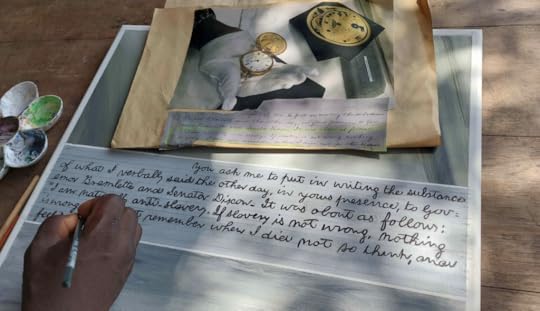

This winter, President Lincoln’s Cottage in Washington, D.C., exhibited “Create to Free Yourselves: Abraham Lincoln and the History of Freeing Slaves in America,” an installation by Georges Adéagbo. In creating it, Adéagbo visited the Library’s Manuscript Division to research Abraham Lincoln’s words and handwriting. Stephan Köhler, Adéagbo’s collaborator and interpreter, accompanied him and translated his remarks here.

Since 1971, Adéagbo has been assembling found objects into award-winning private installations and environments. He studied law in Côte d’Ivoire, continued his studies in France and returned afterward to his native Benin.

Part of Georges Adéagbo’s installation on Lincoln.

Part of Georges Adéagbo’s installation on Lincoln.How do you conceive of projects?

All my projects are site or theme specific. I do not work like a painter or sculptor, who finishes the production of his works in his studio and then sends them in crates to galleries or museums. All my installations are custom-made, and I realize them after months of preparing the components in the exhibition space, which becomes my studio so to speak. It is a dialogue of request and proposal.

When invited to a group show with a set theme, I start with its title and discuss my contribution with the curators. If it’s a solo show, I will decide on the title. I take my time to think about it, as it influences the perception of the audience.

How do you go about selecting objects?

For each project, I do a research visit to study the space and get the energy of a city or a house, as in this example of the President Lincoln’s Cottage. I see my work as archaeology of mentalities.

In many installations, I write: “Archaeology is the research and discovery of the mysteries and the energies that form a person, a city or an entire country.”

I collect over months both things and images in the city the exhibition takes place and bring them to Benin. There, I write texts about what I saw and glue them with the photos on a big sheet of brown packing paper. Then they are reproduced by sign painters and sculptors.

What drew you to Lincoln?

I first read about him in the late 1990s and was impressed by his determination to educate himself, become a lawyer, run for president and write the Emancipation Proclamation, which led to abolition of slavery.

When I was invited to have a solo show in New York City in 2000, I decided to dedicate it to Lincoln. It was called “Abraham, l’ami de Dieu.” I use references to the Bible as metaphors for justice and prudence, not because I am adherent of the Christian church. I think a lot about Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son. I think achievements and changes can be achieved only through a person making sacrifices.

In 2007, the Philadelphia Museum of Art invited me to reinstall the work in an extended version and bought the installation. At that time, my research was based only on books and the internet.

For the Installation “Create to Free Yourselves,” I received a Smithsonian Institution artists’ research fellowship and spent November 2021 in Washington, D.C.

What did your research involve?

My adviser was Nancy Bercaw, curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. She and her colleagues showed me items Lincoln used — his golden wrist watch, his black coat with worn-out edges — and life casts made of his face and hands. I also viewed the announcement of his death and many lithographs showing him with his family and satires of him by his opponents. I had these images realized by the artist Benoît Adanhoumè, and they appeared on the paintings and banners in the exhibition.

I also viewed images of Lincoln on horseback, commuting everyday between the White House and the cottage. I was impressed by him refusing to have bodyguards. So, I had a sculpture of Lincoln on horseback carved in Benin by Hugues Hountondji, who often works for me.

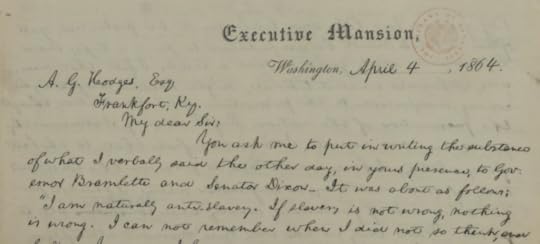

On the walls of Lincoln’s cottage, I saw quotes in Lincoln’s writing and thought they were very inspiring — reproductions of letters and the Emancipation Proclamation. Original handwriting transmits the energy and spirit of the person writing.

So, Stephan Köhler and I asked Nancy Bercaw if she could get us in touch with the curators at the Library of Congress. That’s how we met Michelle Krowl, a Manuscript Division historian, who generously showed us manuscripts by Lincoln from the Library’s collections.

I write a dozen pages myself every day, and I almost felt my hand moving in front of Lincoln’s writing as I gazed. We took photos of Lincoln’s famous April 4, 1864, letter to newspaper editor Albert G. Hodges, in which Lincoln recounts words he uttered in an earlier conversation: “I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.” That seems to me the essence of Lincoln’s attitude.

Almost exactly a year before the end of the war, Lincoln writes a newspaper editor: “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.” Manuscript Division.

Almost exactly a year before the end of the war, Lincoln writes a newspaper editor: “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.” Manuscript Division.How did you incorporate Lincoln’s writing?

I made a collage with the photo of the manuscript and my hand holding Lincoln’s golden pocket watch and gave it to Adanhoumè, who made a wonderful painting from it.

I integrated it in the installation in the Lincolns’ cottage bedroom, where he wrote the Emancipation Proclamation. The process and motivation for abolition was complex, I know, and others were involved, including Frederick Douglass, for example. Yet, Lincoln made this important first step, which opened doors for others.

What’s next for the installation?

It will soon be reinstalled in a modified version at Chesterwood, the former summer home and studio of Daniel Chester French, in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. He is the artist who created the Abraham Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. [French’s papers are at the Library.] The opening will be July 29. Then, toward the end of this year, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art will host the installation.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 5, 2023

Danny Elfman, Legendary Film Composer, Debuts Classical Work at LOC

Danny Elfman has composed or produced scores for more than 100 films, including blockbusters such as “Batman” and “Men in Black.” He’s composed themes for TV hits, as classic as “The Simpsons” and as recent as “Wednesday.”

He was at the Library this week to present something more subtle: the world premiere of his latest classical work.

“Suite for Chamber Orchestra” debuted Thursday night at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church on Capitol Hill as part of an evening concert by the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, honoring the legacy of composer Andre Kostelanetz. The Russian-born Kostelanetz moved to the U.S. in 1922, where he became hugely popular during the middle years of the 20th century. The Library has his papers and commissioned Elfman’s work along with the Andre Kostelanetz Royalty Pool, the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra and the National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland.

“The beautiful thing about concert music is that you can always go back and develop it more,” Elfman said in an interview earlier Thursday with the Music Division’s Paul Sommerfeld, while touring some of the Library’s musical treasures. “With film music, you write it, it’s recorded and it’s gone forever.”

“Suite” is Elfman’s ninth major classical piece, with commissions coming from entities such as the London Philharmonic Orchestra and the Czech National Symphony Orchestra. His first classical piece, “Serenada Schizophrana,” debuted in 2005 at Carnegie Hall in New York and was commissioned and performed by the American Composers Orchestra.

Elfman looks over a selection of classical music scores during a Library tour. Paul Sommerfeld of the Music Division points out highlights. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Elfman looks over a selection of classical music scores during a Library tour. Paul Sommerfeld of the Music Division points out highlights. Photo: Shawn Miller.It might sound like heady work for a guy who started out fronting the rock band Oingo Boingo and whose first film composition was for “Pee-wee’s Big Adventure,” but Elfman’s classical interests run deep.

He grew up in Los Angeles and didn’t take any interest in music until his parents moved across town when he was in high school, meaning that he had to make new friends. One of those was into classical music and played some recordings by Russian composer Igor Stravinsky.

It opened up a “whole new world,” Elfman said. Stravinsky led him to Dmitri Shostakovich and Béla Bartók and finally to Sergei Prokofiev, his true inspiration.

“The first time I heard Prokofiev, I just felt like this was music from my blood,” he said. “I have Russian roots, but knew nothing of Russian music. I was connecting on this deep, almost cellular level.”

Still, he had little formal training – he didn’t finish high school, only getting a diploma later, he said – and fell into a musical troupe in France while on a youthful travel jaunt that was intended to take him around the world on the cheap. Instead, after months of travel, he was back in L.A.,playing in a surrealist music group his brother was putting together, The Mystic Knights of the Oingo Boingo.

Elfman later became the front man as the group transitioned to being a more straightforward rock group just known as Oingo Boingo. The band was more of a cult favorite than a mainstream attraction, but one important fan was an aspiring film director named Tim Burton.

Burton asked Elfman to score his first feature film, “Pee-wee’s Big Adventure,” in 1985. A film/musical partnership was born. “Beetlejuice,” “Batman,” “Edward Scissorhands,” “Batman Returns,” “Big Fish,” “The Nightmare Before Christmas” and “Corpse Bride” among others followed.

The Library’s copyright deposit of Elfman’s 1988 score for “Beetlejuice,” on display for Elfman during his Library tour.

The Library’s copyright deposit of Elfman’s 1988 score for “Beetlejuice,” on display for Elfman during his Library tour.He’s also done dramas (“Good Will Hunting,” earning one of his four Oscar nominations), and any number of superhero films, from “Spider-Man” to “Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness.”

It’s this work that’s won Elfman, now 69, a host of younger fans.

David Betancourt reports on all aspects of comic books culture for the Washington Post and teaches a course on the subject at the University of Maryland. There’s a scene in “Batman” in which our hero (Michael Keaton) is driving his Batmobile with Vicki Vale (Kim Basinger) through Gotham that he always plays for students.

“I always tell the class to listen to Elfman’s score in a scene with few words and feel how impactful it is in pushing the tension, mystery, fear and suspense,” he says. “I want them to know that Elfman’s score is a strong supporting character in the movie that helped it become a classic.”

Given all this success in a high-profile industry, why pursue the hard work of composing classical music, in which the audiences and public attention are but a fraction?

“I love writing for film, but you can’t write what you want to write,” Elfman said. “You have to write to serve the film.” Besides, he added: “I’m just trying to challenge myself. You keep yourself moving or you die, artistically. You become a relic.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers