Library of Congress's Blog, page 22

July 26, 2023

NLS Debuts Site for Spanish-Language Audio and Braille

This is a guest post by Kathryn Marguy, a public affairs specialist at NLS.

At the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled (NLS), we’ve been delighted by the enthusiastic reader response to the rollout of a Spanish site at the top of our home page.

Since the site’s February debut, readers have jumped at the chance to find the newest reading materials in Spanish-language audio and Braille. The new site also features Spanish-language guides to our most popular resources, including frequently-asked questions about our BARD Mobile reading app, information about our accessible music scores and details on how to obtain a free currency reader for blind and visually impaired users.

News of the site was picked up in the media by the likes of Telemundo and Voice of America. Our network libraries across the country have been good partners in getting the word out. For months after the February launch, NLS sitewide traffic was led by areas with large Spanish-speaking demographics, including Puerto Rico.

This focus on Spanish readers is part of NLS’s efforts to expand our offerings of books in international languages.

Thanks to a landmark international copyright agreement known as the Marrakesh Treaty in 2013, NLS has built its collection to offer accessible-format books in more than 26 languages (and counting!) including Japanese, German and Arabic. We’ve seen our catalog of books in languages other than English bloom from a few hundred to tens of thousands. This includes popular new releases, beloved classics and everything in between. More than 50 countries now participate.

The result? NLS readers have downloaded more than 100,000 books made available through the treaty. That’s part of the explosion of titles that helped us launch our new Spanish-language site.

Of course, this is just an extension of what NLS has always done. For more than 90 years, we have distributed free books in audio and Braille to patrons across the country who otherwise cannot read print books because of a visual, physical, or reading disability. We are always adopting new technologies — from circulating the first ever audiobooks on vinyl records in the 1930s to designing our celebrated BARD Mobile app and our Braille eReaders, where patrons can download titles instantly, from a library of hundreds of thousands of books and magazines.

In the years ahead, we look forward to helping more of our patrons share the transformational power of reading. If you or someone you know could benefit from accessible reading materials, visit us anytime.

July 21, 2023

Remembering Tony Bennett, Gershwin Prize Winner

Tony Bennett, the Gershwin Prize-winning singer who knew his way around torch ballads, jazz standards and just about every nook and cranny of the Great American Songbook, has passed away at 96. He dazzled and charmed everyone at his Gershwin concert in 2017 and we won’t forget him, his grace and his impeccable touch with a song, anytime soon.

“Tony’s music and voice transcended generations and musical categories and his name is synonymous with the ‘Great American Songbook,’ which he has enriched with a multitude of songs known and loved throughout the world,” Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress, said in a statement. “Most importantly, he has stood for ‘the best of the best’ in music, with an unshakeable commitment to excellence and integrity. Our thoughts are with his family and friends.”

His 2017 Gershwin Concert was a stunner, including him performing a spirited version of George and Ira Gershwin’s “They All Laughed.” Stevie Wonder sang, as did Gloria Estefan, Vanessa Williams, Josh Groban and Brian Stokes Mitchell.

“The Gershwins created some of our most beautiful music,” Bennett said at the time. “Their songs had gorgeous poetry and wonderful musicality.”

He sold more than 50 million records in a 70-year career that resulted in a stunning number of awards. He was a Kennedy Center honoree, won a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Grammy Awards and was recognized as a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master.

The Library’s Gershwin Prize for Popular Song honors the legendary Gershwin songwriting team. Bennett was a natural fit. From his first big hit “Because of You,” to his signature song, “I Left My Heart in San Francisco,” to his late-career duets with an array of stars, Bennett found his way into everyone’s playlist. He was the elder statesman of the Gershwin Awards, as other recipients have included Paul Simon, Stevie Wonder, Sir Paul McCartney, Carole King, Willie Nelson, Smokey Robinson and, most recently, Joni Mitchell.

His life was a journey through the heart of the 20th century. Born Anthony Dominick Benedetto in Queens, New York, on August 3, 1926, he was just 10 years old when his father died. It was 1936, the Depression hung over the nation, and the family had little money. He had already started singing, though, and with an uncle involved in vaudeville, he had a start. He also had already begun developing his other lifelong artistic endeavor, drawing and painting.

He was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1944 and fought in the infantry as the allies marched across France and into Germany. His unit took part in liberating a concentration camp.

He was back home in 1946. After three years of studying and singing, he got his first big break when jazz star Pearl Bailey asked him to open for a show in New York. Bob Hope was in the audience and took Bennett on the road with him. That first No. 1 hit, “Because of You,” a lush ballad, came when he was 25.

It was 1951, and he was on his way.

Tony Bennett waves farewell to the audience at his 2017 Gershwin Prize concert, surrounded by fellow performers. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Tony Bennett waves farewell to the audience at his 2017 Gershwin Prize concert, surrounded by fellow performers. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Barbara Millicent Roberts is at the Library — But Just Call Her Barbie

Barbara Millicent Roberts debuted in 1959, when Elvis reigned supreme and Berry Gordy had just founded what would become Motown. “The Twilight Zone” dazzled television viewers. It was long ago and far away.

Sixty-four years down the road, Barbie is bigger than ever and hasn’t aged a day. Her latest film adventure, “Barbie,” hits theaters today, turning the world pink for just a little while, but it seems certain she’ll still be a pop-culture icon long after this escapade fades into the rear view.

Since she’s a veteran pop-culture staple, Barbie has a dream home in the nation’s library. The Barbies in the Geppi Collection, above, are held in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. They appear to come from the early 1960s, when the bubble cut was all the rage. That’s the original, 1959 style of bathing suit on the far right, but Barbie’s hair has already shifted from the original pulled-back look. Fans will recognize the early version of Midge, her best friend, on the left. Ken, who debuted in 1961, skipped our photo shoot.

Ken accessories from the early 1960s. Rare Book and Special Collections. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Ken accessories from the early 1960s. Rare Book and Special Collections. Photo: Shawn Miller.Their adventures would grow to include several pop-culture formats, notably including the comic book.

All these came to the Library in 2018, courtesy of collector and entrepreneur Stephen A. Geppi as part of his landmark 3,000 item collection of comic books, photos, original art, newspapers, buttons, pins and badges, all documenting pop culture. (It included the original storyboards that show the creation of Mickey Mouse.)

Barbie was the creation of Ruth Handler who, along with her husband Elliot, headed up the toy company Mattel. Ruth Handler had seen a racy 1950s German newspaper cartoon, Lilli, which was turned into a doll that was marketed as a gag gift for men. But Ruth saw a market for grown-up dolls intended for girls who could play-act with them, dress and change their looks. They were not asked to be a mother to Barbie, but a best friend.

They sold 300,000 Barbies the first year and have gone to sell more than a billion. It’s a story about a doll who grew up to tell America something about itself.

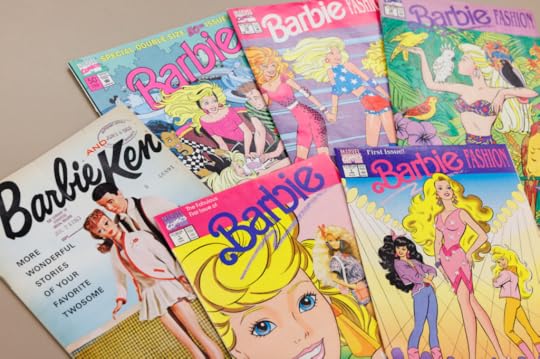

A colorful selection of Barbie magazines from over the years. Serial and Government Publications Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Subscribe

to the blog— it’s free!

A colorful selection of Barbie magazines from over the years. Serial and Government Publications Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Subscribe

to the blog— it’s free!

July 20, 2023

Oppenheimer: The Library’s Collection Chronicles His Life

Julius Robert Oppenheimer, leader of the Manhattan Project and father of the atomic bomb, is the subject of “Oppenheimer,” due out in theaters tomorrow.

His morally complex, intellectually voracious life has been the subject of an astonishing amount of worldwide scientific, cultural, political and historic interest since 5:29 a.m., July 16, 1945, when the first atomic bomb was detonated in New Mexico, ushering in the nuclear era. The test site was named Trinity and the plutonium device was called Gadget. The scientific director of the project, the American who beat the Germans and the Russians to create the world’s most devastating weapon, was J. Robert Oppenheimer.

The Trinity explosion. Image courtesy of the National Security Research Center at Los Alamos National Laboratory.

The Trinity explosion. Image courtesy of the National Security Research Center at Los Alamos National Laboratory.Weeks later, the bomb was put to devastating use in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

So cataclysmic were the bombs that the world was permanently altered by the work Oppenheimer led at what is now known as the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico.

“I think it is true to say that atomic weapons are a peril which affect everyone in the world,” Oppenheimer said in a speech in November 1945, when the atomic age was just a couple of months old.

The Gadget, the first atom bomb. Image courtesy of the National Security Research Center at Los Alamos National Laboratory.

The Gadget, the first atom bomb. Image courtesy of the National Security Research Center at Los Alamos National Laboratory.Today, the heart of the world’s fascination with Oppenheimer’s life lies in the Manuscript Division of the Library, where his papers are preserved in more than 300 boxes that occupy a line of files that would stretch, if stacked end to end, more than 120 feet. That’s not including more than 70 boxes of research files compiled over 20 years by Martin J. Sherwin for his part of the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer.” (Kai Bird shared the Pulitzer as a co-writer.) Those stretch another 27 feet.

It’s a stunningly complete and intellectually dizzying collection.

It’s filled with more than 76,500 items, including handwritten letters, transcripts of illegal FBI wiretaps, brain-busting physics, Nobel Prizes, Red scares, New Deal politics, his own early struggles with his Jewish identity, stormy personal letters and granular detail of lives lived under immense pressure.

Most of all, the files belie its subject’s staggering intellect. Oppenheimer, a polymath genius, spoke six languages and authored dozens of influential research papers, widely regarded by his peers as a phenom. He was friends with Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr and a vast array of world-changing scientists.

He was born in 1904 into a wealthy New York family from the upper East Side and always supported by a trust fund, but seemed uncomfortable with such privileges. He often gave friends extravagant gifts, picked up the tab on group nights out and dressed plainly.

He blew through his studies at Harvard University and the University of Cambridge in the U.K. before obtaining his PH.D. at the University of Göttingen, in Germany. He was a professor in physics at two different California universities by the time he was 25.

He was charismatic and cheerfully eccentric (that ubiquitous porkpie hat), beloved by his students and adored by many of the women who passed through his life. Friends remarked on his empathy, his impeccable manners and his good taste in art, wine and literature.

He was rail thin – standing 5’10”, he often weighed less than 125 pounds – but was an accomplished sailor and horseback rider. After a family vacation in a remote area of New Mexico, bought a bare-bones house in the region, falling in love with the high mesas and the austere desert beauty. He became adept at horseback and hiking expeditions into the mountains that could stretch for more than a week in spartan conditions. Later in life, he bought a remote beachfront property on the north shore of St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands, building a house there for his family. (It is today known as Oppenheimer Beach.)

Despite his personal wealth and professional fascination with theoretical physics, he was deeply interested in the practical aspects of social injustice.

The civil war in Spain and the rise of Hitler in Germany worried him, as it did many American intellectuals in the 1930s. Domestically, he was active in causes for civil rights for African Americans, wage rights for workers and immigrants, and took leadership roles in union causes. He helped German Jews escape Nazi Germany and joined a campaign to racially integrate San Francisco swimming pools. He was sympathetic to many causes supported by communists, though he apparently never joined the party.

He never second-guessed his work in building the atom bomb, not even after its use on Japan when the war was nearly over, but he did not support nuclear proliferation and specifically opposed building a hydrogen bomb, which caused much suspicion in government circles.

Oppenheimer and Gen. Leslie Groves, military director of the Manhattan Project, at the Trinity Site. Image courtesy of the National Security Research Center at Los Alamos National Laboratory

Oppenheimer and Gen. Leslie Groves, military director of the Manhattan Project, at the Trinity Site. Image courtesy of the National Security Research Center at Los Alamos National LaboratoryFor the rest of his life, he was hounded by federal agents for any real or perceived ties to the communism. This including being followed, his home and work phones being illegally wiretapped and FBI listening devices being placed to capture his private speech. Eventually, the Atomic Energy Commission concluded in 1954 that he was a “loyal” American, but still stripped him of his security clearances. It was, historians have agreed, one of the lowest points of the McCarthy Era.

He spent the remainder of his life leading the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton. He died in 1967 at the age of 62, felled by throat cancer, a result of his decades of chain-smoking.

He was widely viewed as a victim of McCarthyism excesses. Last year, the U.S. Department of Energy vacated the AEC’s 1954 ruling, saying the process was a “flawed process that violated the Commission’s own regulations.”

The passage of time and the development of research, Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm wrote in a statement, had revealed the bias and unfairness of the hearings, “while the evidence of his loyalty and love of country have only been further affirmed.”

The Trinity monument. Images courtesy of the National Security Research Center at Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Subscribe

to the blog— it’s free!

The Trinity monument. Images courtesy of the National Security Research Center at Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Subscribe

to the blog— it’s free!

July 17, 2023

When Susan (B. Anthony) Met Harriet (Tubman)

This is a guest post by Amanda Zimmerman, a reference specialist in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. It appears in the July-August issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

The 15 lines, scrawled inside an aged biography on the Library’s shelves, casually record a singular moment in suffrage history: the chance meeting of two larger-than-life women at the dawn of a new century, as they looked back on past struggles and ahead to the possibilities of the next generation.

In 1903, Susan B. Anthony, pioneer of the American woman’s suffrage movement, donated her personal library to the Library of Congress. Anthony, helped by her sister Mary and suffragist Ida Husted Harper, prepared the books for their journey from Anthony’s home in Rochester, New York, to the nation’s capital.

Susan B. Anthony. Photo: Bain News Service.

Susan B. Anthony. Photo: Bain News Service.During this process, Anthony annotated many of the volumes, often including personal remembrances and commentary. One noteworthy annotation recalls the day Anthony unexpectedly met another figure that looms large in U.S. history: abolitionist and suffragist Harriet Tubman.

Tubman led more than 300 slaves to freedom on the Underground Railroad. After the Civil War, she settled in Auburn, New York, and turned her attention to women’s rights.

In 1869, she had been the subject of a biography, “Scenes in the life of Harriet Tubman,” based on author Sarah Bradford’s interviews with her the year before. Anthony owned a copy of the second edition, retitled “Harriet, the Moses of her People,” and before sending the book to the Library inscribed it with a personal memory of meeting Tubman at a gathering in 1903:

Lines from Susan B. Anthony’s book inscription, with “Harriet Tubman” underlined for emphasis. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Lines from Susan B. Anthony’s book inscription, with “Harriet Tubman” underlined for emphasis. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.“This most wonderful woman — Harriet Tubman — is still alive. I saw her but the other day at the beautiful home of Eliza Wright Osborne, the daughter of Martha C. Wright, in company with Elizabeth Smith Miller, the only daughter of Gerrit Smith, Miss Emily Howland, Rev. Anna H. Shaw and Mrs. Ella Wright Garrison, the daughter of Martha C. Wright and the wife of Wm. Lloyd Garrison Jr. All of us were visiting at Mrs. Osbornes, a real love feast of the few that are left, and here came Harriet Tubman!”

The recollection, short and matter of fact, nevertheless reveals the thrill Anthony felt: She underlined Tubman’s name each time and finished it off with an exclamation point.

Tubman was friendly with prominent suffragists and helped inform their understanding of the particular struggles Black women faced in the fight for suffrage and equality. Anthony came from a family of staunch abolitionists and met and befriended Tubman, Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth and others throughout her life.

This is not to say that the campaigns for Black suffrage and women’s suffrage were in perfect accord. From the early days of the suffrage struggle, there were heated clashes over whether white women should include Black suffrage in their campaign. This tension complicated both efforts but ultimately left Black women out of the suffrage fight for many years.

While these two women fought parallel, though separate, battles, their paths occasionally did cross. Anthony introduced Tubman at the 1904 meeting of the National American Women’s Suffrage Association in New York. Perhaps it was at the chance meeting at the Osborne house that Anthony asked Tubman to participate in the association’s meeting the following year.

Though neither Tubman nor Anthony lived to see women attain the right to vote in 1920, both left legacies of progress. This book, and the happy memory it brought to Anthony, marks a moment of joy and hope between two influential women soon to pass their batons to the next generation.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 13, 2023

Crime Classics Returns: “The Thinking Machine”

This is a guest post by Grace Conroy, an intern in the Library’s Publishing Office .

Intriguing, astonishing, mind-boggling — such are the intellectual feats of professor Augustus S. F. X. Van Dusen, otherwise known as “The Thinking Machine” in Jacques Futrelle’s short story collection of the same name. The 1907 volume, the latest in the Library’s Crime Classics series, follows the eccentric scientist on a series of exploits as he attempts to prove there is no such thing as a perfect crime.

As Crime Classics series editor Leslie S. Klinger states in the introduction, Futrelle’s first story about the Thinking Machine introduced “one of the most admired creations in the history of crime fiction.”

Born in Georgia in 1875, Futrelle was a journalist who worked his way from Atlanta to Boston by the time he was in his late 20s. He dabbled in crime writing until 1905, when his newspaper, the Boston American, published “The Problem of Cell 13.” Published in six parts, the story follows neurotic professor Van Dusen, nicknamed the Thinking Machine, as he vows to break out of prison using only his cleverness and ingenuity. In the story, the details of his eventual escape astonished the professor’s colleagues and the prison’s warden. In real life, it fascinated readers around the country.

The Thinking Machine’s frail body, wild blond hair and aloof mannerisms made him a peculiar protagonist. Stories featuring the enigmatic professor proved so popular that Futrelle left his newspaper job and churned out more than 40 crime stories to meet the public’s demand, as well as several novels.

This Crime Classics entry includes “The Problem of Cell 13” and six other stories dedicated to the Thinking Machine’s clever mind. Standouts include “The Flaming Phantom,” revealing how Van Dusen debunks the theory of a haunted house; “The Scarlet Thread,” in which he solves the mysterious case of a murderous gas light; and “The Mystery of a Studio,” in which he takes on the case of a missing girl from an infamous painting. Throughout these adventures, the Thinking Machine is accompanied by journalist Hutchinson Hatch, who serves alternately as accomplice, interlocutor and stand-in for the reader, in the tradition of the Holmes-Watson partnership.

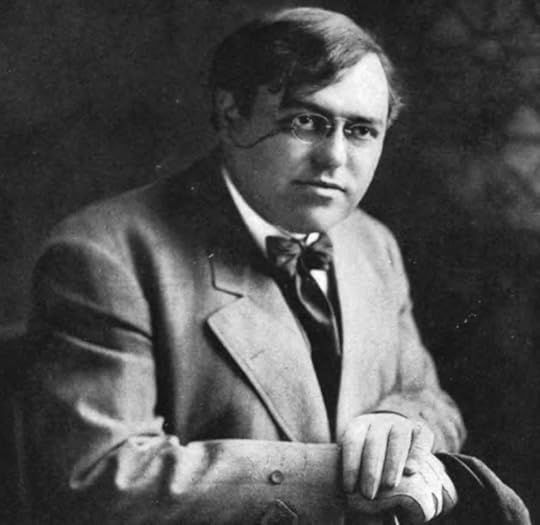

Jacques Futrelle. Photo from the frontispiece of “My Lady’s Garter.”

Jacques Futrelle. Photo from the frontispiece of “My Lady’s Garter.”Futrelle’s life ended prematurely. He and his wife, May, booked first-class passage on the Titanic’s maiden voyage. On April 14, 1912, the “unsinkable” ship failed to evade a large iceberg. May recounted her final moments with her husband in the April 20, 1912, edition of The Pensacola Journal:

“Jack died like a hero. … He was in the smoking room when the crash came. The noise of the smash was terrific. I was going to bed. I was hurried from my feet by the impact. I hardly found myself when Jack came rushing into the room.

“‘The boat is going down; get dressed at once,’ he shouted. When we reached the deck everything was in the wildest confusion. The screams of women and the shrill orders of the officers were drowned intermittently by the tremendous vibrations of the Titanic’s deep bass fog horn. …

“I didn’t want to leave Jack but he assured me that there were boats enough for all and that he would be rescued later.

“‘Hurry up, May! You’re keeping the others waiting,’ were his last words as he lifted me into a lifeboat and kissed me good-bye. I was in one of the last lifeboats to leave the ship. We had not put out many minutes when the Titanic disappeared. I almost thought as I saw her sink beneath the water that I could see Jack standing where I had left him and waving at me.”

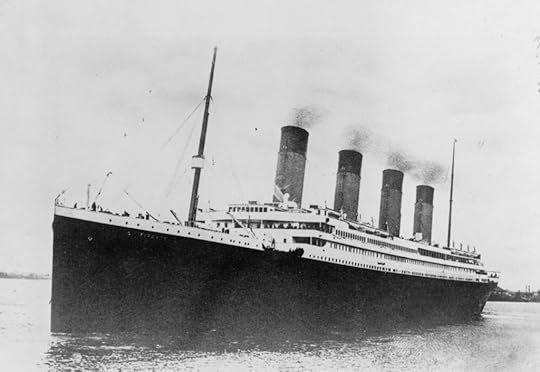

Approximately 1,500 people died aboard the Titanic, including Jacques Futrelle. Photo: New York World-Telegram & Sun. Prints and Photographs Division

Approximately 1,500 people died aboard the Titanic, including Jacques Futrelle. Photo: New York World-Telegram & Sun. Prints and Photographs DivisionAfter her husband’s death, May published two of Futrelle’s novels. She also published two of her own, “Secretary of Frivolous Affairs” and “Lieutenant What’s-His-Name.” (During their marriage, May had helped write the first part of “The Grinning God,” as a creative challenge for Futrelle to finish the second half.)

A few of Futrelle’s stories had lives beyond their pages. “The Problem of Cell 13” was adapted into two television episodes; other novels, unrelated to the Thinking Machine, were also adapted into films.

Paramount Artcraft Pictures used “My Lady’s Garter” to produce the 1920 silent film of the same name. Futrelle’s “thrilling mystery-romance,” as it was promoted by Paramount, centered around the Countess of Salisbury’s stolen jeweled garter. Raymond L. Schrock also adapted Futrelle’s novel about a battle of wits between English and American diplomats, “Elusive Isabel,” into a six-reel picture. The Library also has descriptive material relating to copyright registrations for “A Model Young Man” and “The Diamond Queen.”

To promote “My Lady’s Garter,” Paramount Artcraft Pictures released a press book. National Audio-Visual Conservation Center.

To promote “My Lady’s Garter,” Paramount Artcraft Pictures released a press book. National Audio-Visual Conservation Center.His influence wasn’t lost on other writers, either. More than a century after Futrelle’s death, Gene Weingarten, the two-time Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist at the Washington Post, nicknamed his laptop Augustus Van Dusen because it was. of course, a thinking machine.

The world lost an incredible crime author on the Titanic but his legacy endures in his short stories and novels and their film adaptations. This most recent publication of the Library’s Crime Classics series reintroduces readers to the excitement of Jacques Futrelle’s mysteries.

Library of Congress Crime Classics are published by Poisoned Pen Press, an imprint of Sourcebooks, in association with the Library of Congress. Each volume includes the original text, an introduction, author biography, notes, recommendations for further reading and suggested discussion questions from mystery expert Leslie S. Klinger. “The Thinking Machine,” published on June 6, is available in softcover ($14.99) from booksellers worldwide, including the Library of Congress shop.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 10, 2023

Library’s Baseball Card Collection: It’s (Mostly) the Topps!

This story also appears in the July-August issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Baseball’s best players come together each summer for the annual All-Star Game, as they will tomorrow night in Seattle. An even greater gathering of stars permanently resides in the baseball card collections of the Library.

The 2,100 cards in the Benjamin K. Edwards Collection, for example, depict many legendary figures from the sport’s first half-century: Ty Cobb, Christy Mathewson, Walter Johnson and Cy Young. To those, the Library recently added over 45,000 cards — most produced by Topps — that illustrate stars of more recent decades.

The cards were collected by Peter G. Strawbridge, who preserved complete sets of every major league team from 1973 through 2019 along with some Boston Red Sox cards from earlier years. His family donated the collection to the Prints and Photographs Division, which recently placed a sampling online.

Behind each card is a story of dreams realized or lost.

Derek Jeter was drafted sixth in the 1992 draft. He made his Major League debut in 1995. Prints and Photographs Division.

Derek Jeter was drafted sixth in the 1992 draft. He made his Major League debut in 1995. Prints and Photographs Division.Here’s a fresh-out-of-school Derek Jeter, just drafted by the New York Yankees and looking every bit a kid. No one who picked up that card could know what glory lay ahead: Jeter went on to win five World Series and play in 14 All-Star Games, and in 2020 he was inducted into the Hall of Fame.

In his final at-bat of the 1972 regular season, Pittsburgh Pirates great Roberto Clemente doubled to left center and became just the 11th player in history to reach the 3,000-hit milestone. Three months later, on New Year’s Eve, he died in a plane crash while trying to deliver supplies to earthquake victims in Nicaragua.

Early the next year, Clemente was voted into the Hall in a special election, the first Latin American player inducted into the shrine. Around that time, Topps decided to issue the Clemente card now in the Library’s collections — a tribute to one of baseball’s brightest stars, fallen too soon.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 3, 2023

Our Invitation to You: Celebrate America’s 250th Anniversary

In 2026, just three years from now, we will commemorate the United States Semiquincentennial and the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

The Library of Congress, along with other Federal agencies, will be taking part in this commemoration. We’ll be sharing our great collections and insights from our incredible staff, and inviting you to rediscover the Library of Congress for yourself.

In the lead-up to this milestone, the America250 Commission has launched America’s Invitation, a nationwide campaign for all Americans to share stories and hopes and dreams for our future.

America’s Invitation is an opportunity for Americans across the country, from every background, to take part in reflecting on our past and looking to the future by sharing their stories, and the things they love about America, as we continue to strive for “a more perfect union.”

Taking part in America’s Invitation is easy — visit stories.america250.org to share photos, videos, artwork, essays, songs, poems, or anything else that highlights what America means to you and how you hope to commemorate this milestone. This content may be showcased by America250 on its website, in videos, on social media, and more. Together, these contributions will highlight what makes America unique and ensure we are building a commemoration that includes all of us.

For some inspiration, you might enjoy this “From the Vaults” episode about the Dunlap Broadside, the first printing of the Declaration of Independence that was printed throughout the night of July 4, 1776. This is how the text of the Declaration was first sent out into the world:

And if you’re looking for more about the history of the Declaration of independence, we have you covered.

Over the next three years, America250 will continue to host commemorative events across the country. To learn more, visit America250.org, and follow the Commission on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

June 27, 2023

The Lasting Magic of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

Mari Nakahara, curator of Architecture, Design, and Engineering in the Prints & Photographs Division, chooses favorite collection items related to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. This article appeared in slightly different form in the May-June issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Architect and Artist Together

In 1981, Paul S. Oles, one of the world’s premier architectural illustrators, created a drawing to reveal Chinese American artist and architect Maya Lin’s design for the memorial in a realistic style. Lin shyly asked Oles to include her in the drawing; Oles agreed on one condition: She would appear on his arm. In the image at the top of this post, you can see them walking together along the top of the monument at the left.

Portrait of Maya Lin

Lin poses in front of her wax piece “Phases of the Moon” in this photograph by Nancy Lee Katz at the Gagosian Gallery in Los Angeles in 1998.

Detail from photo portrait of Maya Lin. Photo: Nancy Lee Katz. Prints and Photographs Division.

Detail from photo portrait of Maya Lin. Photo: Nancy Lee Katz. Prints and Photographs Division.Vietnam Memorial Original Design

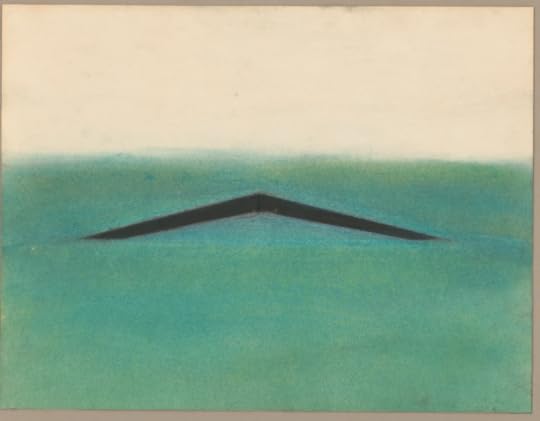

The Vietnam War resulted in over 58,000 U.S. military fatalities and divided the nation. Veteran Jan Scruggs proposed a memorial to help bring people together. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund received over 1,400 proposals for the design competition, held in 1981. Maya Lin, a 21-year-old student at the Yale School of Architecture, created the winning drawings, one of which is seen below. Lin situated the wall so that one invisible axis connects the Vietnam Veterans Memorial to the Lincoln Memorial and one of the black granite walls vanishes into the ground in the direction of the Washington Monument.

One of Lin’s original drawings, showing a front, slightly elevated view of the black granite wall of the memorial. Prints and Photographs Division.

One of Lin’s original drawings, showing a front, slightly elevated view of the black granite wall of the memorial. Prints and Photographs Division.A Living Memorial

Since its completion in 1982, the Vietnam Memorial has remained a popular site for visitors to Washington, D.C. Many leave personal mementos and letters commemorating lost family members or friends — the men and women whose names are inscribed on the walls. The National Park Service collects and archives these tributes.

Items left at the memorial. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

Items left at the memorial. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 20, 2023

Historical Newspapers Reveal Hidden LGBTQ+ History

This is a guest post by Megan Metcalf, a reference librarian in the Newspaper and Current Periodical Reading Room.

The Library’s collections of historical newspapers uniquely illuminate the spectrum of LGBTQ+ history.

These rich resources provide a record of LGBTQ+ lives that otherwise would have gone undocumented. In these pages, one can find the history of resistance, community and, of course, love.

In a story entitled “Thirteen Years a Girl-Husband,” The Ogden Standard issue of June 13, 1914, dedicated almost an entire page to the story of Ralph Kerwineo of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Born female, Kerwineo lived as a man and even married a woman — twice.

Kerwineo was eventually outed and arrested on charges of disorderly conduct. But, on May 15, 1914, The Tacoma Times published Kerwineo’s own account of their experiences on the front page. These stories were picked up by other papers around the country. This kind of firsthand perspective is rarely available and offers a glimpse into how LGBTQ+ individuals and couples survive when their love and identities are criminalized.

The Ogden Standard issue of June 13, 1914, devoting coverage to the story of Ralph Kerwineo. Chronicling America, Serial and Government Publications Division.

The Ogden Standard issue of June 13, 1914, devoting coverage to the story of Ralph Kerwineo. Chronicling America, Serial and Government Publications Division.“Evidence of Homosexuality,” published by the Evening Star on Oct. 3, 1955, reports on a police raid on the Pepper Hill Club in Baltimore and the arrest of 162 people. The Cumberland Evening Times provided more context the same day, describing a woman who was “… convicted of assaulting policemen who tried to load her into a paddy wagon.”

This Pepper Hill raid occurred 14 years before the Stonewall riots of 1969. News coverage of this raid and similar ones allows researchers to expand the timeline of LGBTQ+ resistance, which began long before Stonewall.

More than a half-century later the Ogden newspaper’s report on Kerwineo, The New York Times described the first Pride march in a June 29, 1970, story headlined, “Thousands of Homosexuals Hold a Protest Rally in Central Park.” Newspaper coverage of Pride events through the years can include attendee estimates, photographs, quotes, names of participants or sponsoring organizations as well as locations of events.

The articles highlighted in this piece can all be found online in Chronicling America and in print or on microfilm in the Newspaper and Current Periodical Reading Room. Many newspapers can also be accessed on eresources.loc.gov.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers