Library of Congress's Blog, page 18

December 27, 2023

Black Dressmakers for First Ladies

This story also appears in the January-February 2024 issue of the LIbrary of Congress Magazine.

Two Black seamstresses have left their mark on White House fashion history, as Elizabeth Keckley and Ann Lowe designed dresses for two of the nation’s most famous first ladies, Mary Todd Lincoln and Jacqueline Kennedy, respectively.

Both designers developed their craft despite the brutal influences of slavery and Jim Crow segregation. Keckley (also spelled Keckly) was born into slavery in 1818 in rural Virginia until buying freedom for herself and her son in her mid-30s. Lowe, born in 1898 in Alabama, learned from her grandmother, who was born into slavery, and her mother, who ran the family’s dress shop.

Both women designed for famous women other than first ladies. Keckley, just a few years out of slavery, made custom dresses for, ironically, Varina Davis, wife of U.S. Sen. Jefferson Davis from Mississippi, the future president of the Confederacy. Lowe, nearly a century later, designed couture for the Rockefellers, the Roosevelts and other high-society names.

Both also left an indelible mark on how their most famous clients are remembered.

Elizabeth Keckley, 1870. Photo: Unknown. Wikimedia commons.

Elizabeth Keckley, 1870. Photo: Unknown. Wikimedia commons.Keckley is remembered by historians today not so much as a groundbreaking fashion designer but as an activist (she was a co-founder of the Contraband Relief Association) and the author of “Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House,” her memoir of her close friendship with the emotionally volatile first lady. She was such a regular part of the Lincoln family’s domestic life that she combed Abraham Lincoln’s hair before his public appearances. He addressed her as “Madam Elizabeth.”

An excerpt from after Lincoln’s assassination:

“Returning to Mrs. Lincoln’s room, I found her in a new paroxysm of grief. Robert was bending over his mother with tender affection, and little Tad was crouched at the foot of the bed with a world of agony in his young face. I shall never forget the scene — the wails of a broken heart, the unearthly shrieks, the terrible convulsions, the wild, tempestuous outbursts of grief from the soul.”

The memoir was such an outrage at the time — viewed as a shocking breach of privacy, though it had been a well-intentioned effort to gain sympathy for Lincoln — that it was withdrawn from circulation almost immediately. (The Library has a copy.) Lincoln never spoke to her again. Her career and health slowly declined and she spent her last years in the National Home for Destitute Colored Women and Children, which had been founded by her relief association. She died in 1907.

Mary Todd Lincoln wore this purple velvet skirt and daytime bodice for the social season of 1861-62. It is believed to have been made by Elizabeth Keckley. Smithsonian National Musuem of American History.

Mary Todd Lincoln wore this purple velvet skirt and daytime bodice for the social season of 1861-62. It is believed to have been made by Elizabeth Keckley. Smithsonian National Musuem of American History.But the book had a second life for historians and writers, including George Saunders, winner of the Library’s 2023 Prize for American Fiction. Saunders drew on Keckley’s details of the Lincoln’s grief after the death of their 11-year-old son, Willie, in “Lincoln in the Bardo,” which won the Man Booker Prize.

“I don’t think (the book) would exist, if I hadn’t read her memoir,” Saunders told the New York Times in 2018.

By contrast, Lowe only made one dress for Jacqueline Kennedy, but it was a stunner: Her wedding dress for her 1953 marriage to John F. Kennedy, then a U.S. senator. That storybook wedding was perhaps the cornerstone of the Camelot myth of the Kennedy administration, and Lowe’s dress was a central character in that foundational event.

Vanity Fair, describing the dress earlier this year:

“The pristine pleating on the gown’s bodice, intricate scallop pin tucks, and complex rosette embellishments with dainty wax orange blossoms nestled in the center — all meticulously done by hand — are trademarks of Lowe.”

The future first lady wasn’t a fan of the dress — she had wanted a French designer — and only told reporters that it was made by a “colored dressmaker.”

Lowe was not deterred. Her career in New York high fashion flourished. In 1965, she told television talk-show host Mike Douglas that the sole point of her career, from her roots in the violent racism of 19th-century Alabama to the civil rights movement, had been “to prove that a Negro can become a major dress designer.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

December 22, 2023

Holiday Cheer? Try These Seasonal Favorites

Every year, a handful of holiday stories pop up as reader favorites in the Library’s archives.

During the last three weeks of December, familiar stories return to the top of our “most read” list. Some are more than a decade old, others just a few years. Some are sentimental, others are relate the backstories of holiday traditions. But they all share something that people like during these short days, long nights and chilly weather — a good story.

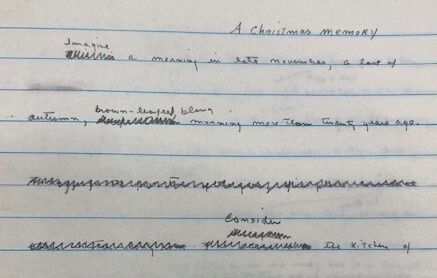

Here’s the beginning of one: “Imagine a morning in late November.”

That’s the start of Truman Capote’s 1956 classic short story, “A Christmas Memory.” It’s the bittersweet tale, heavily autobiographical, of his childhood relationship with his eccentric elderly relative, Nanny Rumbley Faulk.

Famously, she arises one morning each year, their old Alabama house so cold that frost ices the windowpanes, and exclaims, “Oh my! It’s fruitcake weather!”

The Library has a significant collection of Capote’s early-career papers, including his handwritten first draft of the story. We wrote about how the story came to be two years ago and it grows more popular each holiday season. Readers comment that they are moved not just by a nostalgia for the rural, innocent era he describes, but by their own childhood memories of seeing stage, film and television adaptations of the story.

The opening page of “A Christmas Memory” in Capote’s handwriting. Manuscript Division.

The opening page of “A Christmas Memory” in Capote’s handwriting. Manuscript Division.Elsewhere, readers are in more of an investigative mood, pondering the age-old question: Who the heck invented Christmas tree lights, anyway?

We addressed this question early in our online history and revisit it every few years. As it turns out, the answer is pretty straightforward: Thomas Edison, the inventor of the light bulb, and Edward H. Johnson, his friend and business partner. The takeaway is that almost as soon as there were electric lights, people started putting them on Christmas trees. (The Library has a phenomenal collection of Edison’s early films and recording, by the way.) Still, that didn’t mean it caught on with the masses. It took more than four decades for the idea to catch on across the country and that eventual explanation involves President Grover Cleveland and a teenager name Albert Sadacca.

Hard to imagine the National Christmas Tree without lights. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith, 1997. Prints and Photographs Division.

Hard to imagine the National Christmas Tree without lights. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith, 1997. Prints and Photographs Division.Other readers are piqued by the ubiquity of those lovely red flowering plants you see in every office lobby at Christmas. The plants are native to Mexico and Central America, where they have been known for ages as cuetlaxóchitl in Nahuatl, the regional language.

We call them poinsettias, and buy them in astonishing numbers each holiday season, due to the efforts of Joel Poinsett, a U.S. diplomat in Mexico in the early 19th century, who brought them back to the U.S. and first popularized them. As to their commercial success today, that involves a California flower-growing businessman named Albert Ecke and his son, Paul.

Curl up with any of these short pieces and enjoy the holidays!

A “Gibson girl” style illustration, 1910. Illustrator/publisher unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

A “Gibson girl” style illustration, 1910. Illustrator/publisher unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

December 15, 2023

All I Want for Christmas Is … Mariah Carey at the Library?

Is it even Christmas if Mariah Carey doesn’t drop in on your holiday party?

The entertainment icon surprised a festive crowd during the Library’s Santa Claus edition of “Live! At the Library“ last night, making an entrance as her signature hit, “All I Want For Christmas Is You” played in the Great Hall.

Decked out in a stage-worthy sparkling dress and pink high heels, she picked up the song’s framed certificate of induction from the National Recording Registry from Librarian Carla Hayden and – like most everyone else at the party – posed for a couple of pictures by the Christmas tree.

Carey made the visit during a whirlwind trip through Washington during a one-day break from her Christmas concert tour. She’s back in concert tonight in Baltimore.

She was delighted earlier this year when “All I Want” was inducted into the recording registry, earning a forever home in the Library as part of the country’s official heritage in music and sound recordings. During an interview about the honor, she accepted an invitation to visit when she was next in Washington, leading to last night’s appearance.

Carey cowrote the song with Walter Afanasieff in 1994. Billboard Magazine puts it at No.1 in its list of “Greatest Of All Time Holiday 100 Songs.”

“I wanted (the song) to embody all the things I didn’t have when I was a kid,” she said.

Mariah Carey at the Christmas tree in the Great Hall. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Mariah Carey at the Christmas tree in the Great Hall. Photo: Shawn Miller.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

December 13, 2023

Home Alone? Check Out The 2023 National Film Registry!

Brett Zongker, chief of media relations, contributed to this report

Twenty-five influential films from the past 102 years have been selected for the 2023 National Film Registry, Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden announced today, inluding blockbusters such as “Fame,” “Home Alone” and “Apollo 13,” the popular romance “Love & Basketball” and influential feature films and documentaries such as “12 Years a Slave,” “Matewan,” “Alambrista!” and “Maya Lin: A Strong, Clear Vision.”

“Films are an integral piece of America’s cultural heritage, reflecting stories of our nation for more than 125 years,” Hayden said. “We’re grateful to the film community for collaborating with the Library in our goal to preserve the heritage of cinema.”

Spike Lee, whose “Bamboozled” became the fifth film he’s directed to be inducted into the registry, was thrilled at the news, as was Hollywood veteran Ron Howard, whose “Apollo 13” marked his directorial debut on the registry.

“An absolute highlight,” Howard said of his experience shooting the film, which drew on the real-life story of the aborted Apollo 13 mission to the moon. “It’s a very honest, heartfelt reflection of something that was quite American, which was the space program at that time and what it meant to the country and the world.”

Lee’s “Bamboozled,” a biting satire about the racial dynamics of blackface in pop culture, was not loved by critics or the box office when it came out in 2000, but has since gained an appreciation for its willingness to confront the issue in cinema history.

“It’s my fourth decade of filmmaking and I don’t remember saying to myself, ‘Don’t do this because the audience might not like it,’ ” he said. “….That didn’t matter to me because I was showing the truth as I see it.”

Jacqueline Stewart, chair of the Library’s National Film Preservation Board, said this year’s selections show the nation’s cultural diversity and storytelling range, finding deep humanity across a range of genres.

A particular theme this year was Asian Americans and their experiences. “Maya Lin,” the documentary about the young Asian American architect who designed the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and the Civil Rights Memorial, won the 1995 Academy Award for best documentary feature for director Freida Lee Mock, herself of Asian American heritage.

“Maya, her work and the film – it has a national resonance and is an important part of who we are as Americans,” Mock said in an interview.

A scene from “Matewan,” John Sayles’ 1987 film about a coal workers strike in West Virginia. Image courtesy of Anarchist and Criterion.

A scene from “Matewan,” John Sayles’ 1987 film about a coal workers strike in West Virginia. Image courtesy of Anarchist and Criterion.Other Asian-themed films include “Cruisin’ J-Town,” a 1975 documentary about jazz musicians in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo community, and the Bohulano Family Film collection, home movies from the 1950s-1970s shot by a family in the Filipino community of Stockton, California.

Finally, there’s Ang Lee’s 1993 film, “The Wedding Banquet,” a comedy about a Taiwanese immigrant in New York City who sets up a marriage to a Chinese woman to conceal his gay relationship from his visiting family. The film was a surprise international hit, propelling Lee on to an Academy Award-winning career, directing films such as “Sense and Sensibility,” “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” and “Brokeback Mountain.”

“I didn’t make the movie to be influential, but it was,” Lee said in an interview. “I see since the movie, whether it’s cross-culture or gay issues, some major breakthroughs, certainly in Taiwan and the Chinese community because the movie was well-liked. It just eased into people’s lives quite naturally.”

Twenty-five films are selected each year for their cultural, historical or aesthetic importance and must be at least 10 years old. The selections bring the number of films in the registry to 875. Some of these films are among the 2 million moving image collection items held in the Library. Others are preserved by the copyright holders or other film archives.

The public submitted 6,875 titles for consideration this year. Several titles selected this year drew significant support, including “Home Alone” and “Terminator 2: Judgment Day.” (Submit a nomination for the 2024 registry here.)

A scene from 1977’s “Alambrista!” Photo: “Alambrista!” (1977). Image courtesy of Criterion.

A scene from 1977’s “Alambrista!” Photo: “Alambrista!” (1977). Image courtesy of Criterion.This year’s selections date back to a 1921 Kodak educational film titled “A Movie Trip Through Filmland” about how film stock is produced. The most recent films are 2013’s Oscar-winning “12 Years a Slave” and the Oscar-winning documentary “20 Feet from Stardom.”

McQueen, the British director of “12 Years a Slave,” said he was attracted to the story of the film’s real-life protagonist, Solomon Northup, because he saw him as “an American hero.”

“Slavery for me was a subject matter that hadn’t been sort of given enough recognition within the narrative of cinema history,” he said. “I wanted to address it for that reason, but also because it was a subject which had so much to do with how we live now.”

Other Hollywood releases this year include Disney’s 1955 beloved animation “Lady and the Tramp” and the Halloween and holiday favorite “The Nightmare Before Christmas.” Plus, there’s “Love & Basketball,” which has grown new audiences over the years as a classic love story.

Released in 2000, the film was an intensely personal project for director Gina Prince-Bythewood. She grew up in Pacific Grove, California, and was a high-school basketball and track star. She ran track while in college at UCLA.

“A great deal of this film was autobiographical,” she said. “Monica’s (the film’s heroine) character, growing up as an athlete, all the feelings she felt, feeling ‘othered’ and different as if something’s wrong with her because she loves sports. All those were things that I had to deal with growing up, being a female athlete and with my parents.”

Turner Classic Movies will host a television special Thursday, Dec. 14, starting at 8 p.m. EST, to screen some of this year’s selections.

The Library will show two of the films in December: “The Nightmare Before Christmas” on Dec. 21 at 6:30 p.m. and “Home Alone” on Dec. 28 at 6:30 p.m. Free timed-entry passes are available at loc.gov/visit.

Films Selected for the 2023 National Film Registry

A Movie Trip Through Filmland (1921)Dinner at Eight (1933)Bohulano Family Film Collection (1950s-1970s)Helen Keller: In Her Story (1954)Lady and the Tramp (1955)Edge of the City (1957)We’re Alive (1974)Cruisin’ J-Town (1975)¡Alambrista! (1977)Passing Through (1977)Fame (1980)Desperately Seeking Susan (1985)The Lighted Field (1987)Matewan (1987)Home Alone (1990)Queen of Diamonds (1991)Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991)The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993)The Wedding Banquet (1993)Maya Lin: A Strong Clear Vision (1994)Apollo 13 (1995)Bamboozled (2000)Love & Basketball (2000)12 Years a Slave (2013)20 Feet from Stardom (2013)Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!It’s

December 7, 2023

Carl Sagan: Childhood Dreams of Space Flight

This is a guest post by Sahar Kazmi, a writer-editor in the Office of the Chief Information Officer. It appears in the November-December issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Children often dream of flying, of traveling to distant worlds. For Carl Sagan, contemplating the unfathomable vastness of the universe was a practically spiritual experience.

The man who would eventually become one of the world’s most distinguished and beloved cosmologists was fascinated by the wonders of space as a young boy.

Captivated by dazzling visions of the future at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, Sagan developed a lifelong passion for the mysteries beyond our planet and the technology that might bring humanity closer to them.

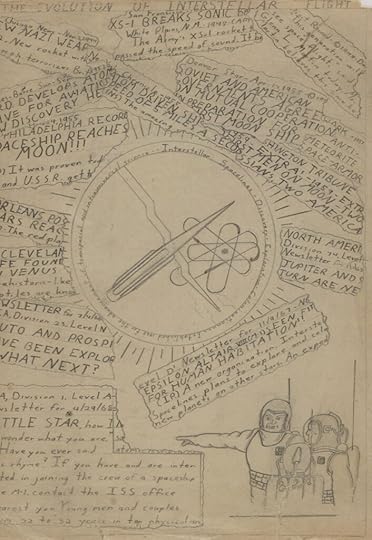

Among the 595,000 items in the Library’s Seth MacFarlane Collection of the Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan Archive is a childhood drawing titled “The Evolution of Interstellar Flight.” Created sometime between 1944 and 1947, when Sagan was 10 to 13 years old, the sketch offers a wondrous vision of adventurers crossing the galaxy.

Carl Sagan’s childhood drawings of space travel. Manuscript Division.

Carl Sagan’s childhood drawings of space travel. Manuscript Division.A collage of hand-drawn headline clippings wraps around a sleek logo for Sagan’s imagined multinational exploratory organization, “Interstellar Spacelines.” A decade before the start of the moon race, one headline proclaims, “Soviet and American Governments Agree on Mutual Cooperation in Preparation for First Moon Ship.” Others read triumphantly, “Spaceship Reaches Moon!!!” and “Life Found on Venus.”

In one of the most thrilling notes of foresight from the young Sagan, three astronauts appear at the bottom right corner of the page. Their uniforms feature bubble helmets, thick jumpsuits and backpacks with antennae — familiar sights to modern readers, but unexpectedly savvy visions from a school kid in the 1940s.

That boyish wonder never left Sagan. Today, his enchantment with the cosmos lives on in an impressive body of work, ready to inspire a new generation of dreamers.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

December 5, 2023

Q & A: Guy Lamolinara, at the Center for the Book

Guy Lamolinara is head of the Center for the Book.

Tell us about your background.

I grew up in a Cleveland suburb. After high school, I attended Ohio State, thinking I wanted to be a dentist. I took all the prerequisites — biology, physics, chemistry — but quickly learned what I most liked to do was write.

I also took a lot of English lit and earned enough credits for a major. I then went to grad school and got a master’s degree in journalism, thinking it was a great way to have a writing career.

Before coming to the Library, I worked at various publications, including the Kansas City Star, Army Times and Congressional Quarterly Weekly Report.

What brought you to the Library, and what do you do?

I came to the Library out of desperation. I hated my job at the time and was willing to go anywhere that would have me. A friend who worked at the Library told me about a job in the Public Affairs Office (now Communications) as editor of the Library’s magazine (then called the Information Bulletin). I was thrilled when I got the call that the job was mine!

But I also thought I would not stay long, that I would be bored and miss the adrenaline dose of daily deadlines. Clearly, I was very wrong.

Thirty-three years later (34 this coming May), I can honestly say I’ve never been bored, that I learn something new almost daily, thanks to the extraordinary people I get to work with and the collections we have. I never cease to be amazed at the knowledge of staff members and how eloquently they talk about the amazing things we have.

I worked in Public Affairs for 12 years, editing the magazine but also doing press relations for this new invention called the World Wide Web. When the internet came along, the Library was way ahead of just about every institution. It had already digitized thousands of items and had been distributing them to schools nationwide on CDs. So, we could immediately put thousands of items online.

The media were intently interested. It gave me the chance to get our name in the pages of virtually every major publication. Networks and newspapers like The New York Times, CNN and PBS were frequently here working on stories.

Did I mention the luminaries I got to meet or see in person? Queen Elizabeth, Prince Philip, Jane Fonda, Mikhail Gorbachev, the Empress of Japan, Ruth Bader Ginsburg. I shook hands with Angela Lansbury. “How lucky you are to work here,” she told me.

After Public Affairs, I went to Strategic Initiatives (now the Office of the Chief Information Officer). That unit directed the National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program. That mouthful of a name was for a project that made grants to institutions wrestling with preservation of born-digital materials. I was the communications officer.

I’ve been with the Center for the Book for about 16 years and its head for about six. The center is a network of 56 affiliates in 50 states, Washington, D.C., and five U.S. territories. Our mission is to promote books, reading, libraries and literacy nationwide. The centers also have a mandate to promote their local literary heritage. Each center takes the lead on how it meets the mission.

The job has taken me to at least half of the states, including Alaska (twice) and Hawaii, and to Puerto Rico. Tracy K. Smith, then poet laureate, read her work during the launch of the Puerto Rico center.

What are some of your standout projects?

The Roadmap to Reading is one of the most rewarding projects I manage. It brings representatives from all the centers to Washington, D.C., during the National Book Festival to promote their state’s literary heritage. It’s inspiring to see families crowd the tables, eager to learn about authors and literature from across the country.

I was also part of the creation of major programs that still exist today, including the National Book Festival, the Prize for American Fiction, the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature program and the Literacy Awards program.

What do you enjoy doing outside of work?

It would be no surprise if I told you I love reading, but you might be surprised to learn that I mostly read classic fiction of dead writers. America has many great living writers. But I think William Faulkner was the greatest writer who ever lived, and Toni Morrison was America’s last literary genius.

What is something your co-workers may not know about you?

My wife and I love taking Amtrak to New York and seeing Broadway shows. For us, there is nothing that compares with seeing a show in the theater district. We’ve been able to travel and stay for free this year in Amsterdam and Italy thanks to my miserly collection of hotel points over many years.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

December 1, 2023

Beer Runs to the White House and Other Long-ago Radio Delights

As the clock struck 12:01 a.m. on Dec. 5, 1933, a truck full of beer departed Anheuser-Busch in St. Louis — a seemingly unremarkable event. That shipment, however, was something special: Prohibition had just ended. Beer was on its way to the White House.

KMOX CBS Radio in St. Louis was on hand to broadcast the celebration to the nation.

In real time, listeners heard brewing magnate August Busch’s delight at releasing the first case of beer bottled at the plant in 14 years. “May I just add a word about good, wholesome beer, which contributes so much to good cheer, good health and true temperance?” he asked.

This slice of American history is just one example of thousands upon thousands of recorded broadcasts that members of the Library’s Radio Preservation Task Force have brought to light or helped to preserve in archives across the country since its launch in December 2014.

The task force enters its 10th year this month with a solid record: It has sponsored three major conferences, each connecting hundreds of specialists; created a searchable database of more than 2,500 radio collections at archives nationwide; and supported dozens of successful grant applications to preserve at-risk recordings.

Its newest project is Sound Submissions, an initiative to facilitate donations of digitized recordings to the Library.

The task force’s work has been “incredibly important” to communicating the breadth and depth of radio collections across the U.S. while underlining the urgency to preserve recordings, said Patrick Midtlyng, head of the Recorded Sound Section.

The National Recording Preservation Board established the Radio Preservation Task Force after a major Library study found that many broadcast recordings had been destroyed or were no longer traceable.

From the mid-1920s until well into the 1950s, radio was the nation’s major source for entertainment and news, as well as a mirror of the times, the 2010 report states. Yet “little is known of what still exists, where it is stored and in what condition,” threatening “an irreplaceable piece of our sociocultural heritage.”

The task force — a consortium of academics, archivists, recording professionals and independent scholars — has responded by raising awareness of the riches of radio history and its power to fill gaps in the American story.

“One thing we started to find almost immediately was different primary source trails in sound that you don’t necessarily find on paper,” Josh Shepperd, the task force director, said. “In other words, the manuscript reading room might have NAACP history, but maybe it doesn’t have the sound history of civil rights activism in Indianapolis.”

Shepperd is a media studies professor at the University of Colorado Boulder. The Library’s vast radio collections and its expert staff and technology quickly attracted him and many others to the project.

“The Library of Congress name has so much resonance with historians,” Shepperd said.

The Library started collecting radio broadcasts in 1938, not long after recording technology — 16-inch lacquer discs at the time — made it possible to capture more than a few minutes of broadcasts.

Networks, with their ample budgets, recorded most early radio.

The NBC collection — around 40,000 hours of news, comedy, live music and drama from 1935 to 1978 — is the Library’s largest and most used radio collection. It includes such iconic recordings as the network’s June 5–6, 1944, broadcast narrating D-Day and Marian Anderson’s April 9, 1939, concert at the Lincoln Memorial after DAR Constitution Hall refused to let her perform because of her race.

The task force’s first project involved inventorying lesser-known American radio collections in archives around the country and developing a searchable database to expand their use.

Shepperd estimates the effort has identified about 80% of existing collections. “I’m certain we haven’t found everything, but we’ve been pretty successful,” he said.

Researchers anywhere can now easily find the Gay Peoples Union Records at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, including the nation’s first regularly scheduled gay and lesbian radio show; a public radio collection on rural life at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, that includes programs like “Shepherds, Bumpkins and Farmers’ Daughters”; and Campus Radio Voice at Columbia University, provider of content to U.S. college radio stations in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Following the task force’s first conference in 2016, its project attracted major media attention. Shepperd recalls doing 30 to 40 interviews, leading to stories on NPR and in The Atlantic, Time and elsewhere.

“All these people realized the same thing we realized, that there’s this whole history here,” Shepperd said. “Why haven’t we touched this?”

An elevated profile led to funding to digitize and preserve collections, including projects previously rejected for support. “Before the task force, there really wasn’t much funding for radio preservation,” Shepperd said.

In 2018, University of Oklahoma Libraries, for example, received $49,900 from the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) to digitize the “Indians for Indians” radio show, broadcast from 1941 to 1976 on the University of Oklahoma’s AM radio station.

Broadcasts include host Don Whistler’s April 20, 1948, entreaty to listeners to “run, don’t walk, to the nearest telegraph station or post office, and get your protest on the way to Washington.”

A congressional committee was then considering abolishing the commission that decided tribal claims against the U.S. government.

Now available online, the recordings are “an important microcosm of U.S. history told through a Native perspective,” in the words of task force member Lina Ortega, a curator at the university.

Shepperd and others helped draft applications to CLIR, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Mellon Foundation and other funders to preserve collections curated by task force members and affiliates — other radio research and preservation groups — and they’ve written letters to support upward of 90 applications.

“We’ve been very successful at attracting grants over the years,” Shepperd said.

He believes the biggest challenge now is saving the local and community collections, many fast deteriorating, that are still out there.

“They’re in people’s basements, attics or garages. It’s usually the people who did their own show,” he said. “So, you have a local talk show host, and they saved all of their recordings. But the station didn’t want it, and they just have it at home.”

Once such collections are digitized, they need an archival home.

Shepperd sees Sound Submissions, the task force’s latest project, as a potential model. Based at the Library, it seeks donations of already digitized small radio collections for the permanent collections.

“Digitization removes a large obstacle to getting a collection,” Midtlyng said. “Much more work and resources are needed to take in a physical collection.”

Task force member Frank Absher, a longtime St. Louis broadcaster and media historian, obtained and digitized the live broadcast documenting the end of prohibition.

“It’s still fun,” he said. “You can hear the end of prohibition the way the rest of the world heard it.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

November 22, 2023

“Maestro” — A Look at Leonard Bernstein’s Papers at the Library

“Maestro,” the film biography of composer Leonard Bernstein, hits theaters this week starring Bradley Cooper as the world-famous musician. Bernstein’s life is documented at the Library in a collection that also seems almost larger than life — some 400,000 items, brought to the Library over half a century.

Not suprisingly, the filmmakers researched the Library’s holdings, spending time particularly on his correspondence. But they also drew on many other items to help the props and costume departments recreate things accurately. The full sweep of the collection includes original music manuscripts, personal letters, photographs, scrapbooks, film scores, audio and film recordings, business papers, concert programs and date books. “Maestro” is a feature film, not a documentary, but it draws deeply from the Library’s well of Bernstein material.

Mark Horowitz, a senior music specialist at the Library and the archivist for the Bernstein Collection, gives a brief tour of the material and its cultural significance in the video above, offering a peek behind the scenes at some of the images and moments that the film dramatizes. (One hint: Bernstein really did have a license plate that read “MAESTRO1.”)

“He was such a larger-than-life figure that I think he fascinates people as a human being, not just as a musician, but the life he led, the influence he had on people and social issues — it just reverberates,” Horowitz says.

Bernstein burst onto the public stage at the age of 25, when he had to fill in as conductor for the New York Philharmonic Orchestra on short notice. His debut, broadcast live on national radio, was such a success that the New York Times published a story about it on the front page. He would go on to lead the Philharmonic for four decades, write the unforgettable score for “West Side Story” and other productions, as well as composing, writing, conducting and educating on almost every platform that existed at the time.

He died in 1990 at the age of 72 after a heart attack.

He has remained such a towering figure that in 2018, on the 100th anniversary of his birth, “More than 2,000 concerts are scheduled on six continents, along with exhibits, including a Grammy Museum touring exhibit; several books; two documentaries in Germany alone; a 25-CD box set of just his musical compositions; and a 100-CD box set of him conducting,” Horowitz noted in a Library of Congress Magazine story that year.

Since then, Stephen Spielberg directed a new version of “West Side Story” and now, in theaters across the country, Cooper is directing and starring in a new feature film about the man himself.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

November 17, 2023

160 Years Later … Where Did Lincoln Stand While Delivering the Gettysburg Address?

“Four score and seven years ago….” those six words, spilling out into the Pennysylvania air in 1863, marked the beginning of one of the greatest speeches in American history and a new era in the life of the nation.

The 160th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address falls on Nov. 19. Thanks to some creative work by researcher Christopher Oakley, historians now have a bit more insight into exactly where the Civil War president stood when he called for a new birth of freedom in the country.

Following a long career in animation — Oakley’s credits include “Dinosaur,” “Stuart Little 2,” “Scooby Doo” and the videogame “Medal of Honor” — he transitioned to a position at the University of North Carolina, Asheville, as a new media studies professor.

There, he has combined a lifelong interest in all things Lincoln with 21st-century digital technology and, for his latest discovery, Library of Congress photographs.

How did your Lincoln Gettysburg Address project come about?

I transitioned from being a digital 3D character animator to an educator in 2009, when I began teaching animation at UNC Asheville.

To challenge advanced students learning Maya, one of the main programs used for digital animation, I created an undergraduate research endeavor in which we would digitally re-create and animate someone everyone knew. I’d always had a fascination with Abraham Lincoln, so I chose him as our subject.

In “The Virtual Lincoln Project,” over 100 students and I spent several years modeling Lincoln in digital 3D, then animating him delivering the Gettysburg Address.

What led you to research where Lincoln was standing?

Our initial plan was to animate Lincoln delivering his Gettysburg Address against a gray, neutral background. But as the project progressed, I decided to put Lincoln in the Soldier’s National Cemetery (now Gettysburg National Cemetery), since he was in Gettysburg to consecrate it.

However, my first foray into what the scene looked like revealed that Lincoln probably was standing in neighboring Evergreen Cemetery when he delivered his remarks. We wanted our depiction of Lincoln delivering the address to be as accurate as possible, and I realized there was a great deal more digging to be done.

I told the students to continue developing the tech, while I did the research on the location, shape and size of the speaker’s platform. Little did I know this would add years to the project!

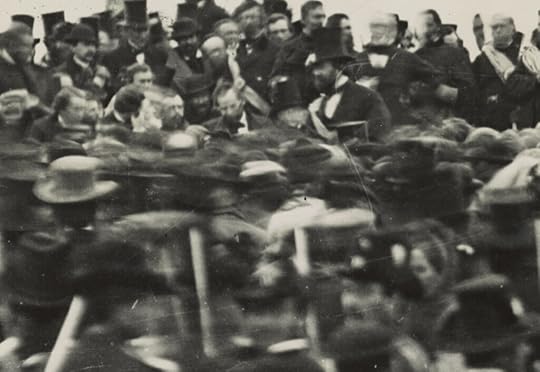

Experts say Abraham Lincoln is the hatless, bearded man, apparently seated, in the middle of the frame. He is just to the left of the tall, bearded man with a stovepipe hat. Photo: Attributed to David Bachrach. Prints and Photographs Division.

Experts say Abraham Lincoln is the hatless, bearded man, apparently seated, in the middle of the frame. He is just to the left of the tall, bearded man with a stovepipe hat. Photo: Attributed to David Bachrach. Prints and Photographs Division.Which photographs at the Library did you use?

There are only six known photographs of the actual dedication of the Soldier’s National Cemetery on Nov. 19, 1863. Experts attribute them to three photographers: Alexander Gardner, Peter Weaver and David Bachrach.

Three of the photos are attributed to Gardner, two to Weaver and one to Bachrach. Bachrach’s is the most famous because, when you zoom in, you can clearly see Lincoln seated on the speaker’s platform. But all six photographs were absolutely critical to the success of my research.

We needed each of them in Maya, combined with Civil War-era maps, Google maps and 3D geographical information system topological maps, to determine definitively where the speaker’s platform was located.

One other Library photograph also played a crucial role. We know that Weaver took the photo held by the Library from the second floor of Evergreen Cemetery’s iconic gatehouse. But the other photograph attributed to Weaver (the one in the private collection) was taken from the attic of the house of local resident William Duttera. The house is no longer standing, and no photographs of it were known to exist, which made it difficult to place Weaver’s location with certainty.

I had a Civil War-era map that indicated the location and footprint of the Duttera house, but I didn’t know what it looked like. I spent a few days looking through the Library’s online Gettysburg photograph collection in hopes of catching a glimpse of it.

In a turn-of-the-20th-century photograph, I found a structure that matched the footprint and was situated exactly where the map indicated the Duttera house was. If not for the photo’s availability on the Library’s website, I would never have been able to confirm that Weaver took his photo from the attic of the Duttera house.

Different locations have been suggested. How did you reach a conclusion?

The written record and eyewitness accounts of where the speaker’s platform stood vary wildly.

In Maya, you can create something called an image plane, which sits in front of the software’s digital camera lens. By loading each Gettysburg photograph into this plane, you can move the camera around in a digital re-creation of the cemetery until what the computer sees exactly matches the photograph.

When you do this for each photograph, you get a highly accurate map of where each photographer stood and what their angles of view were. And because the three photographers were triangulating each other, you can determine the size, shape and location of anything within their views.

We determined the size, shape, and location of our digital platform by how it matched the photographers’ views through our image planes.

If we moved the digital platform just a few inches in any direction that wasn’t correct, it didn’t match any of the views. The same is true for the platform’s size and shape. We also added digital people into our re-creation and placed them according to the photographs, and they match.

What value does the platform’s location add to the historical record?

For well over 150 years, its size, shape and location have been hotly debated. According to the National Park Service, the most-asked question among Gettysburg visitors is about where Lincoln stood.

For the past four decades, scholarship has placed the speaker’s platform — and therefore Lincoln — entirely within Evergreen Cemetery. My research reveals that the speaker’s platform straddled Evergreen and Soldier’s National cemeteries and that Lincoln stood well within the Soldier’s National.

So, for the first time in 40 years, Lincoln is back to where he was actually supposed to be — standing near the graves of the fallen soldiers.

For visitors to Gettysburg, knowing you are standing on the very spot where Lincoln delivered his immortal address transports you in time. In your imagination, you can become a living witness to the event.

A National Park Service marker shows the photo (above) of Lincoln at Gettysburg and notes that he stood nearby while delivering his address. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

A National Park Service marker shows the photo (above) of Lincoln at Gettysburg and notes that he stood nearby while delivering his address. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.View a lecture Oakley delivered about his research at the Lincoln Forum last fall.

November 13, 2023

My Job: Nathan Dorn, Curating Rare Books in the Law Library

Nathan Dorn is the curator of the rare books collection in the Law Library.

Describe your work at the Library.

I am the curator of the rare books collection at the Law Library of Congress, which is mostly a collection of historical printed law books from Europe, the British Isles and the Americas. That role includes a handful of different tasks. I’m the recommending officer for the collection, which means I spend a lot of my time analyzing the collection and shopping for books to acquire that would grow it in useful directions. I’m the reference librarian for questions that relate to objects in the collection or to the subject matter it covers. In addition, I do a lot of outreach work. That includes frequent table-top displays and also longer-lived presentations. I’ve curated two Library of Congress exhibitions. I also write for the Law Library’s blog.

How did you prepare for your position?

Like most of the librarians at the Law Library, I have a Juris Doctor and a master’s in library science. When I was finishing my master’s, I had the good luck to work as an assistant to the previous rare book curator here at the Law Library. I was studying history of the book and descriptive bibliography, so I was really grateful for the opportunity to engage with the collection in hands-on ways.

Before I worked in libraries, I studied classics and then religious studies at the University of Chicago and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. I was in a doctoral program at the University of Chicago when the subject of religion and law pried my attention away from the history of mysticism, which had been occupying me for several years. When I started to look at the history of law, I came to the subject with a raft of foreign language skills that definitely helped prepare me for my work today.

What are your favorite collection items?

This definitely changes all the time. New acquisitions always get my attention. The Law Library recently acquired a copy of the Hamburg Quran, an early edition of the Quran printed in Europe in 1694, and I’m excited to grow the Law Library’s Islamic law collection.

But I also like oddities of law — publications in which law and the administration of the state bump up against the edges of what can be known or realistically controlled: for instance, works on prosecution for witchcraft or heresy; adjudication of miracles; early laws related to mental illness; and medieval and early modern criminal procedure and rules of evidence. Some of my favorite items have been examples of renaissance mnemotechnics, or the art of memory training for lawyers. For example, the works of Johannes Buno are jaw-dropping just from the point of view of their ingenuity.

What have been your most memorable experiences at the Library?

My interactions with visitors are some of the most memorable. Here’s just one unexpected experience: I’m a huge fan of the movie “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” so it was especially fun that I had a chance to take the actor Richard Dreyfuss and his wife on a tour of the Jefferson Building along with a colleague of mine. Dreyfuss and I found our way into a long conversation about historian Nancy Isenberg’s book “Fallen Founder,” which tries to rehabilitate the reputation of Aaron Burr. He was a big fan of the version of Burr that came out of that book, and he told me about it in detail.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers