Library of Congress's Blog, page 16

March 22, 2024

Elton John & Bernie Taupin: Rocking the Gershwins

“My gift is my song,” the lyric goes, and on Wednesday night America repaid the writers with the nation’s highest honor for achievement in popular music.

The Library of Congress bestowed its Gershwin Prize for Popular Song on Elton John and Bernie Taupin, the songwriting duo that over 50-plus years conquered the pop music world. They sold some 300 million records and co-wrote dozens of classics — songs whose timeless melodies today simultaneously bring back a now-long-ago era of music and win over new generations of fans.

“Thank you, America, for the music you’ve given us all over the world. It’s an incredible legacy that you have,” John told the audience at Constitution Hall. “All the wonderful blues, jazz, classical music, all the songs the Gershwin Brothers wrote. … I’m so proud to be British and to be here in America to receive this award, because all my heroes were American. … I’m very humbled by tonight.”

Taupin wrote the lyrics, John composed the music and, together, they produced a string of hits that made Elton the biggest, and most outrageously dressed, rock star on the planet. “Your Song,” “Rocket Man,” “Bennie and the Jets,” “Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me,” “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,” “Daniel,” “I Guess That’s Why They Call It the Blues” – the list goes on and on.

Some of the duo’s biggest fans — major stars in their own right — appeared onstage to pay tribute, a thrill for both the audience and the honorees. It’s like an acid trip, John quipped, seeing all these great artists onstage performing his songs.

There were previous Gershwin Prize recipients Garth Brooks and Joni Mitchell. There were ’80s pop diva Annie Lennox and rising country star Maren Morris, heavy metal icons Metallica and modern folkie Brandi Carlile. And there were contemporary popster Charlie Puth, Jacob Lusk of the Gabriels and SistaStrings, who provided support on violin and cello.

Metallica kicked off the performances, blazing through “Funeral for a Friend/Love Lies Bleeding” — doubtlessly the heaviest sounds in Gershwin Prize history. After blowing the roof off the place, the band walked offstage to a raucous standing ovation, guitarist James Hetfield and bassist Robert Trujillo tossing guitar picks to members of Congress on their way out.

Brooks gave a tip of his cowboy hat to the honorees, then delivered the plaintive ballad “Sorry Seems to Be the Hardest Word,” for which, in a reversal of their usual practice, John wrote the music first as well as the stark opening lyrics: “What have I got to do to make you love me? What have I got to do to make you care?”

Mitchell took the stage, supported by Carlile and Lennox on vocals. She has suffered serious health problems in recent years, and on Wednesday turned a high-energy John-Taupin song about living through a romantic breakup into a personal, bluesy statement of perseverance. “I’m still standing better than I ever did, looking like a true survivor,” she sang, tapping her cane in time to the shuffling beat.

But the highlight in an evening filled with them went to the relatively little-known Lusk, who took “Bennie and the Jets” to church and stole the show. Sitting next to the pianist, Lusk preached the gospel of John and Taupin’s brilliant work, then began “Bennie” as a slow-rolling gospel song. Then came the familiar, pumping beat of John’s smash-hit version, Lusk danced his way to the front of the stage, the audience rose to its feet, clapping along and trading shouts of “Bennie” with Lusk, who exited to enormous applause.

As a performer, John paved the way for other rockers with his often-outrageous stage moves and outfits. His career has been a decades-long parade of wild wigs, giant glasses and preposterous feathers, broken by the occasional appearance onstage dressed as Donald Duck or in a Los Angeles Dodgers uniform covered in rhinestones.

The evening’s host, Broadway star Billy Porter, picked up the mantle of flamboyance with a flurry of costume changes — a faux-furry white outfit with silver boots swapped for a fringed black dress with high, high heels. His appearances culminated with a performance of “The Bitch Is Back,” a number John once called, more or less, his “theme song.” Porter began in the audience, detoured by John and Taupin in the front row to sing a few lines with a bared leg propped up on their seats, then finished onstage with a flourish, tossing his jacket to the audience.

Near evening’s end, John took the stage. Seated at a red piano, he performed “Mona Lisas and Mad Hatters” and “Saturday Night’s Alright (for Fighting)” — the latter derailed by a false start. John laughed and said he’d forgotten what key the song was in, and then kicked back into it.

Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden then came onstage, along with members of Congress, Madison Council Chairman David M. Rubenstein and the two men of the hour.

“Their music has touched the nation and become part of the American songbook,” said Hayden, who, feeling the spirit earlier in the evening, had donned a pair of Eltonesque glasses. “They gave us ‘Your Song,’ and now we give them the nation’s highest award for influence, impact and achievement in popular music: the Gershwin Prize.”

John and Taupin each gave thanks for the honor and delivered a heartfelt tribute to America, its music and the musicians who inspired them long ago: Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Fats Domino, Ray Charles.

“The only good music that I heard was American music — British music sucked,” John said. “Then, suddenly, I heard ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ by Elvis Presley, and my whole world changed. Thank God it did.”

Said Taupin: “Pretty much everything that I’ve written emanates from this country. … I have an American heart, an American soul. I have an American family, I have an American wife, I have American children. I am American.”

“But he drives a Volvo,” John deadpanned to laughter.

They also paid tribute to each other, to a songwriting partnership — and a friendship — that changed the course of pop music and, after 57 years, still is going strong.

“Being able to share success with somebody is the greatest thing you can ever have,” John said. “He is some special person; I love him so much.” And, he added, “Without the lyrics, I’d be working in Wal-Mart.”

Hayden asked John and Taupin if they would favor the audience with another number. She had a particular tune in mind: “Your Song,” the ballad that in 1970 became John’s first top 10 hit — a hit that remains one of those songs everybody knows.

They obliged, together in the spotlight on a darkened stage, Taupin leaning on the piano, listening, as John played and sang: “My gift is my song, and this one’s for you.”

In return, on Wednesday at Constitution Hall, America offered them its thanks and the Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song.

“Elton John: The Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song” will be broadcast on PBS stations at 8 p.m. EST on April 8.

Set list

Metallica, “Funeral for a Friend/Love Lies Bleeding”

Annie Lennox, “Border Song”

Garth Brooks, “Sorry Seems to Be the Hardest Word”

Brandi Carlile, “Madman Across the Water”

Billy Porter, “The Bitch Is Back”

Jacob Lusk, “Bennie and the Jets”

Maren Morris, “I Guess That’s Why They Call It the Blues”

Charlie Puth, “Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me”

Brandi Carlile, “Skyline Pigeon”

Garth Brooks, “Daniel”

Joni Mitchell, I’m Still Standing”

Elton John, “Mona Lisas and Mad Hatters”

Elton John, “Saturday Night’s Alright (for Fighting)”

Elton John, “Your Song”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 19, 2024

Florence Klotz: Costume Design & Broadway History

This is a guest post by Mark Eden Horowitz, a music specialist in the Music Division. It also appears in the March-April issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

The Library’s recently acquired collection of Florence Klotz costume designs are a visual celebration of the art, craft and range of her work.

Many of her shows feature dichotomies of harsh realities and glamorous fantasies, such as in “Kiss of the Spider Woman” where one goes from ragged prisoner garb to the celluloid fantasy of Aurora — the Spider Woman. But however gritty her costumes might get, Klotz undeniably had a magical way with baubles, bangles, beads, rhinestones, sequins, feathers and furs.

In her final show before retirement, the 1994 Broadway revival of “Show Boat” directed by Hal Prince, Klotz designed 585 costumes for 72 actors covering over 30 years of American history. She won her sixth Tony Award for the costumes, more than any previous costume designer.

The Library’s Florence Klotz Collection includes those designs, as well as those for “Follies,” “A Little Night Music,” “Pacific Overtures,” “On the Twentieth Century,” “City of Angels,” “Kiss of the Spider Woman” and many others.

Unlike her costumes, Klotz’s career was not planned or designed; it evolved unexpectedly, as she described it, “mostly through luck.”

Stephen Sondheim and Florence Klotz. Photo: Unknown. Music Division; courtesy of Suzanne DeMarco.

Stephen Sondheim and Florence Klotz. Photo: Unknown. Music Division; courtesy of Suzanne DeMarco. Her parents owned a millinery store, Klotz Brothers (her father named a cloth pattern after her: Florence plaid). She attended the Parsons School of Design but assumed that, after graduating, she would get married and have a family rather than a career. Instead, she and Ruth Mitchell — who began her career as a stage manager, then worked as an assistant to and ultimately co-producer with Prince — became life partners and a theatrical power couple.

In 1941, Klotz got a call from a friend asking if she would like to “paint some materials” at the Brooks Costume Company. Unbeknownst to Klotz, Brooks was the most famous costume company in the theater world. During and right after World War II, many materials were hard to come by so “ordinary materials were painted to look like whatever cloth was desired.” As it turned out, Klotz had a real knack for it.

One day in 1951, legendary designer Irene Sharaff approached Klotz, asking if she would assist her on Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “The King and I.” For several years thereafter, Klotz worked as an assistant to virtually all the major designers of the day — Sharaff, Lucinda Ballard, Miles White, Raoul Pene Du Bois, Alvin Colt — on shows such as “Flower Drum Song,” “The Sound of Music,” “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” and “Silk Stockings.” Ballard eventually nudged a reluctant Klotz into trying her hand as the designer, not an assistant, for shows.

The idea of designing costumes for a Broadway musical alone was daunting, but in 1961 Klotz dipped her toe in, designing the costumes for the Prince-produced, George Abbott-directed play “A Call on Krupin.” (Of course, it was not unusual in those days for a straight play to have a cast of 26.)

For the next few years, Klotz continued to assist on other designers’ shows while increasingly designing for plays on her own. In 1966, again working with Prince, she designed the costumes for her first Broadway musical, “It’s a Bird … It’s a Plane … It’s Superman.” In 1970, she joined with Prince again on the first film for either: “Something for Everyone,” starring Angela Lansbury and Michael York.

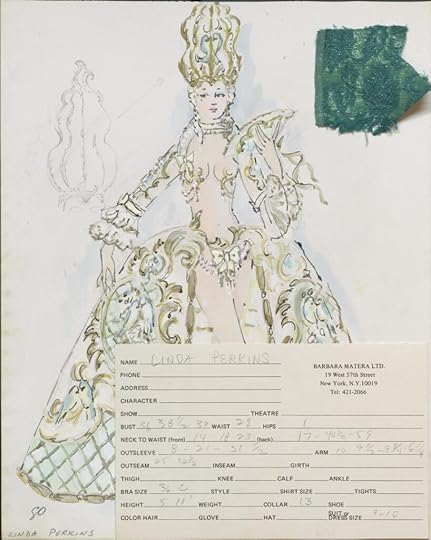

Klotz’s wardrobe sketch for a “Follies” character with a swatch of fabric attached at top right. Artist: Florence Klotz. Music Division, courtesy of Suzanne DeMarco.

Klotz’s wardrobe sketch for a “Follies” character with a swatch of fabric attached at top right. Artist: Florence Klotz. Music Division, courtesy of Suzanne DeMarco.But it was the next show that exceeded all expectations and where Klotz’s genius was widely recognized: the 1971 Stephen Sondheim musical “Follies” — a show whose extraordinary, elaborate, clever and gorgeous costumes won Klotz not only accolades and adulation but also her first Tony AwardTwo more Prince/Sondheim collaborations swiftly followed: “A Little Night Music” (a romantic operetta set in turn-of-the-century Sweden) and “Pacific Overtures,” which tracked Western influence on Japan since the Perry expedition landed on Japanese shores in 1853. Klotz won Tonys for each.

Klotz went on to design costumes for Prince’s film of “A Little Night Music,” starring Elizabeth Taylor (with Klotz receiving an Academy Award nomination). Klotz designed the violet cashmere wedding dress for Taylor’s marriage to Sen. John Warner in 1976, and they would work together again in 1981 on the Broadway revival of “The Little Foxes.” When Klotz was awarded the Patricia Zipprodt Award for Innovative Costume Design in 2002, Taylor wrote her a letter to include in the program: “You’re the best, the funniest, the most talented. If only you could have controlled my boobs when I ran.”

Florence Klotz. Photo: Unknown. Music Division, courtesy of Suzanne DeMarco.

Florence Klotz. Photo: Unknown. Music Division, courtesy of Suzanne DeMarco.Klotz worked on 58 Broadway shows, as an assistant on 26 and the designer on 32. In addition, she designed for opera, ballet (particularly in association with Jerome Robbins) and even “Symphony on Ice” for John Curry, his attempt to legitimize ice dancing as an art form.

The Library’s Klotz Collection includes approximately 2,500 designs, plus hundreds of additional pages of correspondence, notes, photographs and other items. There also are over 40 “Show Bibles” — extraordinary volumes that track every aspect of every costume for a show by performer. The designs themselves range from quick pencil sketches to beautiful hand-painted renderings, often accompanied by fabric swatches and notes.

Looking through the collection, one’s eyes are drawn to the gorgeous designs as works of art. You realize that Klotz was, indeed, an artist.

Then you begin to realize other things, too. She had to be a historian, researching her designs to be appropriate to time, place and situation. She had to be expert in textiles, knowing how each fabric folds, flows, cuts, takes the light, lays, ages and lasts — and how it can be dyed, distressed, appliqued and embellished with sequins, bugle beads, feathers and fur.

She had to be intimate with every aspect of theater: how clothing reveals character (and helps an actor become a character); how it works with sets and props and under lights whose colors change; how costume changes must happen, often at speed, and what will work with dance choreography.

A wardrobe sketch for a “Follies” showgirl includes an illustration of how the clothes will look onstage, a fabric swatch for the material and the costume measurements for the actress. Artist: Florence Klotz. Music Division, courtesy of Suzanne DeMarco.

A wardrobe sketch for a “Follies” showgirl includes an illustration of how the clothes will look onstage, a fabric swatch for the material and the costume measurements for the actress. Artist: Florence Klotz. Music Division, courtesy of Suzanne DeMarco.She also had to be a budgeter, a business manager and a shop manager. The collection includes a three-page working budget for “Pacific Overtures” costumes. The budget has separate columns for materials and construction, using two different companies for the 65 or so costumes the show required. Judging by the document, Klotz apparently was able to negotiate $90,805 down to $81,850.

More than anything, one is awestruck by the extraordinary amount of work involved. Aside from the actual time fitting and constructing the costumes, the collection shows Klotz’s method: how she researched designs, began the design process, came up with significantly different versions of outfits (presumably for the director’s final choice) and created truly ravishing pen-and-ink and watercolor works of art representing them — works that not only show the costume but suggest how it moves, how it will be worn and the character of actor playing the part.

Klotz was a designer of both the conscious and the subconscious, the surface and the hidden. Fortunately, with her collection now at the Library, all is revealed.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 15, 2024

Sandra Day O’Connor Papers Now Open for Research

A major portion of the papers of Supreme Court Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, consisting of approximately 600 containers, opened for research use this week.

Housed in the Manuscript Division, the collection documents the trajectory of O’Connor’s life in politics and law in Arizona and, later, as the U.S. Supreme Court’s first woman justice.

Appointed to the court in 1981, O’Connor served until retiring in early 2006. The case files in the collection document her role as the court’s crucial deciding vote. To varying degrees, they also capture the internal workings of her chambers as well as discussions among her eight peers in determining the constitutionality of the nation’s laws. In addition, the collection chronicles O’Connor’s rise in Arizona state politics as a legislator and judge and her ascension to the national stage.

O’Connor donated her papers to the Library in 1990 and they arrived in installments from 1991 to 2008. The papers join those of more than three dozen other justices and chief justices of the Supreme Court available for research at the Library, including John Marshall, Thurgood Marshall, Hugo Black, Earl Warren, Harry A. Blackmun, William J. Brennan, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and John Paul Stevens.

While serving more than two decades on the court, O’Connor participated in numerous significant decisions on issues ranging from the First Amendment in Lynch v. Donnelly (1983) and Wallace v. Jaffree (1984) to abortion rights in City of Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health (1982), Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992) and Webster v. Reproductive Health Services (1989).

Considered the swing vote on the court, O’Connor was often at the center of many cases when she did not author a majority opinion or dissent.

At this time, the case files and docket sheets are open to researchers through the October 1990 term. Access to cases heard by the court from the 1991 through the 2005 terms remains closed to researchers as long as any justice who participated in the decision of a case continues to serve on the Supreme Court.

Other material open to researchers from her tenure as a justice includes correspondence, administrative files relating to her nomination, speeches and writings by O’Connor. Also open for research are files relating to her political and judicial career in Arizona, book manuscripts and other writings and selected family papers.

O’Connor was born in El Paso, Texas, in 1930. Growing up in Arizona, O’Connor attended Stanford University for both undergraduate and law school. After law school, she served as the first deputy county attorney in San Mateo, California, then as assistant attorney general for the state of Arizona. She entered politics as a state legislator, rising to the position of majority leader in the Arizona state senate.

After retiring from the state senate, O’Connor was appointed to Arizona’s superior and appellate courts. President Ronald Reagan appointed her to the Supreme Court in 1981.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 13, 2024

Crime Classics: Richard Harding Davis Gets Lost “In the Fog”

This is a guest post by Zach Klitzman, a writer-editor in the Library’s Publishing Office .

A dashing explorer returned from an African expedition. A fabulously wealthy and fabulously beautiful princess. A jealous younger brother, angling for the family fortune. Smoky rooms in social clubs. Jewel thieves on trains. And the foggy streets of Victorian London.

These elements form the backbone of “In the Fog,” the latest Library of Congress Crime Classic. This 1901 novella is by Richard Harding Davis, the influential war correspondent, author and playwright. He might be largely forgotten now, but Davis was a Renaissance man of his era, as renowned for his battlefield escapades, famous friends and good looks as he was for his literary and journalistic success.

Davis starts off “Fog” with a framing device: A member of Parliament is enjoying an evening in an exclusive club in London as fellow members regale him with three interweaving tales of murder, robbery and betrayal. Davis also uses a familiar trope of the era — London draped in darkness and fog — to kick things into gear. The first story begins when its narrator, an American naval attaché to Britain, stumbles upon a murder after getting lost one foggy night.

This mysterious atmosphere appeared widely in late 19th- and early 20th-century fiction, series editor Leslie Klinger writes in the introduction. Heavyweights such as Charles Dickens, Robert Louis Stevenson and Bram Stoker often invoked London’s fog and smoke to signify danger, mystery and foreboding. Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, has his famous detective observe that the city’s fog could be so engulfing that “the thief or the murderer could roam London on such a day as the tiger does the jungle, unseen until he pounces, and then evident only to his victim.”

Richard Harding Davis, ca. 1901, the year “In the Fog” was published. Photo: Burr MacIntosh Studio. Prints and Photographs Division.

Richard Harding Davis, ca. 1901, the year “In the Fog” was published. Photo: Burr MacIntosh Studio. Prints and Photographs Division.Davis knew this sort of fog firsthand. In 1897, after leaving a Christmas party with the renowned actress Ethel Barrymore (the great-aunt of Drew Barrymore), Davis remembered that “we rode straight into a bank of fog that makes those on the fishing banks look like Spring sunshine. You could not see the houses, nor the street, nor the horse, not even his tail.” After a memorable encounter with an unexpecting family who believed Barrymore and Davis to be minor royalty, they returned home safe and sound.

Clearly, the episode stirred Davis to imagine a more violent fog-bound incident for the opening of “Fog.”

In fact, many of Davis’ fictional works were inspired by his personal experiences as a journalist abroad. His novel “The Princess Aline,” about an American artist who goes to Europe after falling in love with a portrait of the titular princess, was based on his own infatuation with the empress of Russia, Alexandra Feodorovna. Many of his other books — including “Soldiers of Fortune,” “The King’s Jackal,” “Captain Macklin” and “The White Mice” — were based on his travels.

“The Princess Aline,” 1895. Aline was based on the empress of Russia, Alexandra Feodorovna. Artwork: Charles Dana Gibson. Prints and Photographs Division.

“The Princess Aline,” 1895. Aline was based on the empress of Russia, Alexandra Feodorovna. Artwork: Charles Dana Gibson. Prints and Photographs Division.Davis specialized in war coverage, including the Boer War in modern-day South Africa, the Spanish-American War, the Russo-Japanese War and World War I. He counted Theodore Roosevelt as a friend and rode with TR’s Rough Riders in Cuba — even becoming an honorary member after rescuing wounded soldiers during a raid.

Davis posing with Lt. Col. Theodore Roosevelt during the Spanish-American War in 1898. Publisher: Strohmeyer & Wyman. Prints and Photographs Division.

Davis posing with Lt. Col. Theodore Roosevelt during the Spanish-American War in 1898. Publisher: Strohmeyer & Wyman. Prints and Photographs Division.His journalistic and literary fame led him to the top ranks of celebrity; he befriended Charles Dana Gibson, the illustrator who created the “Gibson Girl” drawings that were the turn-of-the-century paradigm for female beauty. (Gibson later used Harding’s clean-shaven good looks as inspiration for his “Gibson Man” ideal.)

Gibson, a groomsman in Davis’ wedding party, also illustrated several of the writer’s works, including the 1891 story collection “Gallegher and Other Stories.” The title story from that collection, about a newspaper office boy in Philadelphia, is also included in “Fog,” showing that Davis could spin a good yarn set on both sides of the Atlantic.

Harding died of a heart attack in upstate New York in 1916, when he was just 51. He had recently returned from the eastern front in Greece during World War I.

“In the death of Richard Harding Davis, the commonwealth of letters has lost its most picturesque and romantic citizen,” the New York Times Review of Books wrote in a posthumous review of his work.

Though his name has faded in popular culture, his adventures in Central America, Cuba, Europe and Asia — not to mention his tale of mystery in foggy London — live on in his many articles, books, plays and film adaptations.

Library of Congress Crime Classics are published by Poisoned Pen Press, an imprint of Sourcebooks, in association with the Library. “In the Fog” is available in softcover ($16.99) from booksellers worldwide, including the Library of Congress shop.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 7, 2024

My Job: Kathy Woodrell

For three decades, Kathy Woodrell helped bring the Library’s decorative arts collections to light. She recently retired. This story also appears in the January-February issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Describe your work at the Library.

I served as the decorative arts and architecture reference specialist for the General and International Collections. I responded to thousands of questions in person and virtually, identified new resources to enhance the collections and presented many programs and events. I often gave art and architecture tours of the historic Main Reading Room; it was an honor to provide service in this magnificent space.

The decorative arts encompass the history and study of the design and decoration of utilitarian items, including furniture, glass, wood, metal, ceramics, costume, clothing, textiles and crafts. A yearlong special assignment in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division enhanced my knowledge of antiquarian books and encouraged me to recommend decorative arts works for that collection.

Identifying a cherished family object, reuniting childhood pen pals, collaborating with the incredibly knowledgeable staff and mining the expansive collections were incredibly satisfying. I retired from my dream job in 2023 with 34 years of public service at the Library.

How did you prepare for your job?

I was exposed early to architecture, antiques and textiles. My great-grandmother had me quilting at 6 and sewing clothes by 12. My grandmother, an antiques dealer, taught me to look at objects and ask: “What is it, who made it and what do you think it’s worth?” My mother’s distaste for antiques and love of modernism also informed my design aesthetic.

I was raised in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, home to Frank Lloyd Wright’s only “skyscraper,” the Price Tower. Its unorthodox angles, textiles and furnishings fueled my childhood imagination.

I hold a Bachelor of Science degree and a master’s in library science.

What were some of your standout projects at the Library?

I participated in many collaborative displays, tours and presentations on topics including Civil War fashion, Georg Jensen jewelry and modernist furniture. Some coincided with exhibitions at local museums; others featured authors and collectors.

I worked closely with students and faculty in the Smithsonian’s decorative arts and design history master’s degree program for 24 years, assisting with thesis research and advising emerging scholars how to effectively mine the Library’s rich resources.

During the AIDS crisis, I helped make a quilt panel for the NAMES Project to memorialize Library employees who had succumbed. I was honored to teach staff how to sew the name of a beloved person onto the panel.

What are some of your favorite collection items?

The Library’s collections of early journals, magazines and pattern books from the 19th century forward are extensive and invaluable. I adore a small 17th-century book of Psalms with exquisite silk embroidery and seed pearls in Rare Book’s Rosenwald Collection.

Favorite items I added to the Rare Book collections include: a resist-dye pattern book with pages dyed in indigo (1791-1822); a two-volume set of embroidery patterns, each with a silk-worked sampler (1795-1798); a unique work with diagrams and suggestions for improving the Jacquard loom, with fold-out patterns and silk samples (1839); a four-volume set of 600-plus original textile designs from a Parisian design firm (1848-1852); and so many more!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 5, 2024

Womens History Month: Filling in the (Almost) Lost World of Maggie Thompson

This is a guest post by Candice Buchanan, a reference librarian in the History and Genealogy Section.

A teenage girl filling a photograph album with the images of family and friends.

Though the technology may change, the sentiment seems timeless. This girl was Margaret Virginia “Maggie” Thompson, who spent most of her life in Waynesburg, Pennsylvania, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The photographs were cartes de visite and cabinet cards, so popular in the 1870s and 1880s. We turn the album’s pages to see the girl become a woman and her social circle expand. Siblings, neighbors and classmates are eventually followed by a spouse, in-laws and children.

It’s a thick volume of 42 cardstock pages. There are 58 photos, one or two per page with a few loose images in between, nearly all of them bearing a neat, handwritten caption. Since the handwriting appears to be in a more modern style and in a different ink than the dates written on the back of the photos, it may have been one of Maggie’s descendants who affectionately sat with her, late in her life, to pen the inscriptions. Doubtless, unwritten memories and stories were shared.

Then, somehow, the album was left behind. Years later, discovered in a vacant building, Maggie’s keepsake was rescued and brought to the Cornerstone Genealogical Society in Waynesburg for preservation. Though I’m now a genealogist at the Library, I grew up around Waynesburg (in Greene County, in the far southwestern corner of the state) and still run a volunteer digitization project for the community.

When Maggie’s album was handed to me, I was transfixed. Here was this unknown woman’s personal life story, summed up in a single volume.

Photographs are historical records, not merely illustrations. A personal album is a window into the vanished social life of a family and community. Scrapbooks are particularly valuable because they amount to a visual diary, with as much unintentional historical information in the pictures — clothing and hair styles, prices, cars, roads, stores, landscapes — as intentional information.

I was further compelled by Maggie’s album because it portrayed a woman’s personal history. Any genealogist can tell you that while researching centuries of archival documents, official records and narratives of public events, one sees just how often women have been minimized or omitted completely.

So I felt a personal responsibility and an almost compulsive need to decipher her story, to reconstruct the full life only hinted in the photographs. I began to research the contents of the album, digging through local cemetery, census, courthouse and newspaper records; federal and military records; and the kaleidoscope of archival material at the Library.

First, I built genealogical/local history profiles for every person in the album to understand how Maggie may have known them so as not to miss any clues or connections.

The biological family tree was no problem.

Maggie was born in 1855, the daughter of John Thompson and Maria Meegan, in tiny Waynesburg, where the population was between 1,000 and 5,000 for all of her life. She married John Flenniken Pauley and raised five children. She died in 1937.

It turns out that Maggie’s paternal grandmother — pictured in the album — was the sister of my great-great-great-grandfather. It also was easy to distinguish family names and relationships and to identify local friends. Photographer stamps revealed where the images were taken, filling in some of the geography of her life.

But there was a mystery here, too.

Several images were not from Greene County and seemed to have no connection to her at all. I focused on nine pictures taken in Trumbull County, Ohio, during the 1870s. What made that place and these people so important to her?

There was only one clue. One man, identified as “Chas. Bradley” in the Trumbull photographs, had a surname that was also found in Greene County. So I delved into the local records on the Bradley family to see what I could find out.

Charles Bradley’s photo in Maggie Thompson’s scrapbook. Photo: O. Warren. Cornerstone Genealogical Society Collection.

Charles Bradley’s photo in Maggie Thompson’s scrapbook. Photo: O. Warren. Cornerstone Genealogical Society Collection.Charles Bradley, it turned out, was a Greene County native about a dozen years older than Maggie. He enlisted in the Union Army at 18 when the Civil War broke out and served a little over a year as a musician with Company I, 8th Pennsylvania Reserve Infantry Regiment band. His enlistment records at the National Archives list him as standing 5’7” with blue eyes and brown hair. He came home to resume his work with his father as a tanner and saddler and married a local woman, Mary Ann Cooke.

But he also apparently met a fellow musician in the Army, William Henry Dana, who had served with two units from Ohio. After his discharge, Dana pursued formal musical education and in 1869 founded Dana’s Musical Institute in Trumbull County (now known as the Dana School of Music | Youngstown State University).

Now, back at the Library, I went to the card catalog and looked up local histories of Trumbull County and bingo! There was the Dana family and the institute. Since the Library has extensive holdings in the nation’s music history, I checked the Music Division’s archives and was delighted to find original sheet music from the institute, which captures the spirit of the school’s compositions.

More importantly for my research, I discovered that the division also holds an 1875 edition of the Catalogue of Dana’s Musical Institute. It’s more or less the school’s yearbook.

Sure enough, familiar names popped up. Dana shows up as “Teacher of Theory and Organ; Conductor of Oratorio” and Bradley as “Teacher of Cornet and all Instruments in Brass Band Department, and Band Master.” In the graduates list? None other than “Maggie Thompson, Waynesburg, Pa.”

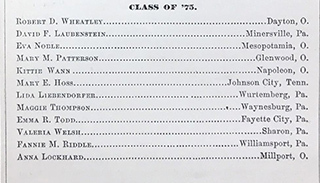

The Dana Institute’s list of graduates includes Maggie Thompson.

The Dana Institute’s list of graduates includes Maggie Thompson.So that was the connection to the Trumbull photos — she’d studied here and made friends. Four more graduates appear in her album, all of whom graduated between 1873 and 1875. Three were men. The one woman, Hettie Jones, was no doubt a friend, as she hailed from Waynesburg, too.

Charles Bradley was likely the common thread. It’s not hard to picture that he started working at the institute and told friends and acquaintances back home. In such a small town, no doubt the young women heard of this and, perhaps since a familiar and trusted face was there, decided to attend.

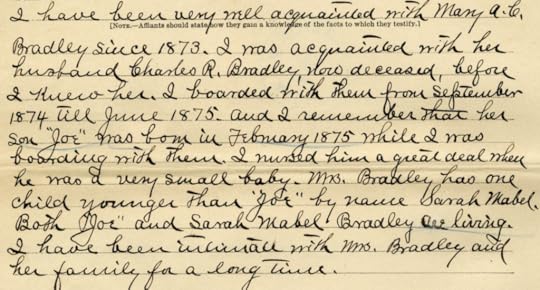

I obtained fantastic evidence of this from the National Archives in Bradley’s Civil War records. Bradley died in 1891, at just 42 years old. His widow, Mary Ann, filed for a military pension. Maggie, then 33, was such a close friend that she filed a handwritten deposition on Mary Ann’s behalf with the pension board.

“I have been well acquainted with Mary A. C. Bradley since 1873,” Maggie wrote in a clear, strong hand. “I was acquainted with her husband Charles R. Bradley, now deceased, before I knew her. I boarded with them from September 1874 till June 1875 … (their) son ‘Joe’ was born in February 1875 while I was boarding with them.”

Maggie Thompson’s handwritten deposition. National Archives.

Maggie Thompson’s handwritten deposition. National Archives.She goes on for a few lines, saying how she’d played with Joe when he was an infant, adding that the couple later had a daughter, Sarah Mabel. Mary Ann Bradley’s pension request was approved and one can see that the two women had a bond that would have lasted throughout their lives.

The connections with the Bradley family illuminate Maggie’s life in ways that could have easily been lost. Family history is always human history, and humans like to do and see and go. Full histories can rarely be assembled. But in this case, Library collections, together with resources from Maggie’s hometown and Civil War files scanned at the National Archives Innovation Hub, made it possible to reconstruct this chapter of Margaret Virginia Thompson’s story.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

February 28, 2024

Black History Month: Spike Lee and “Bamboozled”

Spike Lee has been making films that respond to “The Birth of a Nation,” D.W. Griffith’s influential 1915 film that glorified the Ku Klux Klan and made extensive use of blackface, throughout his career.

In the early 1980s while still in graduate school, he made “The Answer,” a short film about a Black filmmaker who is given $50 million to remake Griffith’s film. In 2018, he co-wrote and directed “Black KkKlansman,” based on the true story of a Black cop who infiltrated the Klan. It was nominated for six Academy Awards, including for best picture. (Lee and three other writers won for best adapted screenplay.)

And then there was “Bamboozled,” his 2000 satire about Black actors in blackface in a television series. The show’s creator, a Black television writer, intends it to be a scathing condemnation of blackface, only to see the show become a massive hit. The film, which Lee intended as a direct response to “Birth,” was inducted into the National Film Registry in December, his fifth film to be so honored.

His focus on “Birth” stems not just from its role in the early 20th century, but how it was being taught at the end of it. The day the film was screened for his class at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, he says there was nothing about the film’s glorification of the KKK, its demonization of Black people or its proud embrace of white supremacy.

“All they talked about was the great techniques, or how D.W. Griffith was called the father of cinema,” he said in an interview for the film registry. “But they never talked about the fact that this film gave new life to the Klan. This film was directly responsible for Black people being lynched, killed. … It brought back the Klan’s prominence.”

“Birth” was the nation’s first blockbuster, so much so that it is credited with being the birth of Hollywood as the film industry’s headquarters. Based on Thomas Dixon’s 1905 novel “The Clansman” and the hit play that ensued, the three-hour film version portrays the South as being the victim of Reconstruction, with white women in danger of lecherous Black men. The Klan comes in to save the day.

While the book, play and film all drew strong condemnation from several quarters of society, including Black social organizations, much of white America loved it, many thinking it to be an accurate history. This included President Woodrow Wilson, who screened it at the White House and famously called it “history written in lightning.”

Klan membership boomed across the country. Lynchings and violent racist attacks grew. In 1925, some 30,000 Klansmen marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington. As late as the 1970s, Klan leader David Duke was showing the film to potential recruits.

Blackface entertainment, meanwhile, was accepted by white audiences for most of the 20th century, before eventually becoming reviled — if not career-killing — by the turn of the century, when “Bamboozled” came out.

Not surprisingly, the film was controversial upon release, opening to mixed reviews. People just did not want to see blackface in any context, Lee remembers. The film’s advertising poster, showing caricatures of two Black children happily eating watermelon, was so shocking that Lee says The New York Times initially refused to publish it, even as an advertisement.

“ ‘Spike Lee’s off his rocker, why is he dredging all this stuff back up from the past?’ ” is how he remembers the general reaction.

He didn’t pull any punches in the movie, although he did make the film’s satirical intent plain in the opening scene, in which the movie’s main character gives the definition of “satire” in voiceover. He didn’t want anyone to miss the point.

But time has a way of telling the truth, and the issues in “Bamboozled” remain persistent. One example: “American Fiction,” the new film about a Black novelist whose book mocking Black stereotypes is also accepted as a straightforward hit, is up for several Oscars, including best picture. It’s based on the book “Erasure,” which was published the year after “Bamboozled” came out — more than two decades ago.

“Eventually people see what I was trying to do at that time and understand it

somewhat better,” Lee says. “One of the most powerful sequences I think I’ve ever done is the closing scene of ‘Bamboozled,’ where we show historically, visually, the hatefulness of white people in blackface — Judy Garland, Mickey Rooney, Eddie Cantor, Bing Crosby — just the debasement of who we are as a people.”

It’s a stark message, he says, that’s been current in cinema since “The Birth of a Nation” and the birth of the film industry.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

February 26, 2024

Library Conservation Specialists Help Save Books, Artifacts After Disasters Around the World

It was late November last year, and journalist Peter Hirschfeld waded through a dark basement on the outskirts of downtown Montpelier. More than four months earlier, a massive flood had inundated the Vermont state capital and cleanup continued.

“There’s ankle-high water, and it smells like raw sewage,” Hirschfeld said on the Brave Little State podcast. The July 10 and 11 flood, he told listeners, was the worst “anyone who lives here can remember.”

In the weeks after the flood, federal agencies, including a team from the Library’s Conservation Division, traveled to Vermont to offer services and expertise. The Library’s involvement reflects a decades-long history of advising on ways to salvage cultural artifacts after disasters.

“We’re a library, and we provide information to people and answer their questions. So, if you have questions about damaged items, we will help you,” said Andrew Robb, head of the Photo Conservation Section. “It also informs us of what we can do better internally.”

Robb coordinates the Library’s Preservation Emergency Response Team. Working with the U.S. Capitol Police, the Architect of the Capitol and the Library’s Security and Emergency Preparedness Directorate and Facility Services Division, its members respond around the clock to incidents in Library buildings that might harm collections.

By deploying off-site, Conservation Division staff members add to the division’s first-hand knowledge about how disasters, most of which involve water, can affect cultural artifacts.

After Vermont’s floods, four division staffers — book conservator Katherine Kelly, objects conservator Liz Peirce, preservation education librarian Jon Sweitzer-Lamme and Lily Tyndall, a general collections conservation technician — traveled to locations around Vermont for 16 days as part of an effort organized by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

They supported a program called Save Your Family Treasures, which provides demonstrations on how to salvage wet artifacts. The program is a joint effort of the Heritage Emergency National Task Force, a FEMA subdivision, and the Smithsonian Institution’s Cultural Rescue Initiative.

Upon arriving in Vermont, the Library team trained fellow responders in techniques such as mold mitigation. In turn, the staffers familiarized themselves with how Save Your Family Treasures operates and learned how to interact with people after traumas. Then they hit the road.

At stations in FEMA disaster recovery centers and at state fairs, they educated people about low-cost methods to rescue soaked and dirty possessions.

“If you’re talking with someone whose basement flooded, you need to give them information about things they can buy at the dollar store or in the hardware isle of their local store,” Kelly said.

Team members demonstrated how to immerse photographs in make-shift baths made from aluminum roasting trays, gently brush away grime, then hang them to dry.

“It wouldn’t look exactly as pristine as when you had those photos before, but at least you wouldn’t have lost your family history,” Kelly said.

Objects conservator Peirce spoke with people about resuscitating a “surprising range of things” — wedding sets, a cookie jar someone’s mother made, a baby book that included scraps of textiles.

The Conservation Division’s external outreach began in 1966 in Italy. A flood in Florence killed dozens of people, destroyed or badly damaged many masterpieces and submerged tens of thousands of books in the city’s Biblioteca Nazionale, Italy’s national library, in water.

English conservator and bookbinder Peter Waters, known for his work on such world historical tomes as the “Book of Kells,” traveled to Florence with a group of others to help. They came to be known as “mud angels” for their rescue of artifacts and books — not just fine art volumes but also general collections.

At the time, the Library had a preservation officer, but its conservation program was in its infancy. The flood raised a bright red flag about the need for more.

“It’s a real pivot point in the history of conservation in this country,” Robb said.

Following his work in Florence, Waters came to the Library with members of his team. As the Library’s first conservation chief, he applied lessons from Florence to care of the Library’s collections. He also established a policy of providing technical assistance beyond the Library’s walls.

“We are structured and founded in a way that’s directly related to how he responds to all of these things in Florence,” Robb said of the Conservation Division.

In the decades since Florence, Library specialists have advised disaster victims around the world.

Specialists traveled to Saint Petersburg, Russia, after water damaged millions of volumes in a 1988 fire at the Academy of Sciences Library; to the University of Hawaii, Manoa, after a 2004 flood drenched some 90,000 maps; to Japan’s National Diet Library in the wake of the country’s devastating 2011 tsunami; and to New York City after Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

Most often, though, Conservation Division experts offer guidance by phone or email. Before Robb went to New York after Sandy to help set up a recovery center recommending ways to treat water-damaged items, he answered questions from his office in the Madison Building.

“Frankly,” he said, “the most impact I had was on the phone.”

Timing was a definite impediment for conservators in Vermont — the Library team arrived weeks after the flood when mold had set in, causing permanent damage to many belongings. Even earlier, some people had thrown out valued possessions, thinking they were beyond salvage.

“The more effective teaching we were doing was how to prepare for next time,” Kelly said. “We delivered the message that with fairly swift, easy action, you can save the things that are truly treasures.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

February 15, 2024

Tim Gunn on Fashion

—Tim Gunn is an academic, bestselling author and television star. He won an Emmy Award for his role as host of “Project Runway.” He wrote this piece for the January-February issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, which is devoted to fashion.

I make a pronounced distinction between fashion and clothes. Fashion bubbles up from a context, one that is societal, historical, cultural, economic and even political. Fashion designers are a barometric gauge of our society and culture. They need to know the news headlines, what books and films are commanding attention, the frequented blogs and podcasts and the daunting content and volume of streaming platforms, not to mention social media. These elements are responsible for fashion’s constant change.

Clothes, on the other hand, don’t have to change. They can remain static for decades. Consider the L.L. Bean catalog (for which I have tremendous respect and from which I own quite a few items): Bean’s clothing staples have remained largely unchanged for years, and that’s a good thing. Let’s say you want to replace a worn out pair of blucher mocs you bought 12 years ago. That same pair is still there, waiting for your purchase.

For the sake of comfort, propriety and protection, we need clothes. But we don’t need fashion. We want fashion, but we don’t need it. The cultural forces that exist will have us believe that it’s our responsibility as citizens of the world to know, and ideally embrace, the latest fashion trends and movements. Furthermore, fashion is a pendulum; it swings one way, then another. A current trend is loose, even voluminous, pants. It’s a reaction to the prevalence of form-fitting ones. Fashion wants us to buy things. Otherwise, fashion becomes static and morphs into clothes. Ergo, trends. And a trend is only relevant if it works for you. Otherwise, don’t even consider it, because you’ll look like a fashion victim.

Personal style is a form of semiotics. The clothes we wear send a message about how the world perceives us. That’s a very tall order and one for which we must accept responsibility. I tell people that I don’t care how they dress as long as they accept responsibility for their decision making. Some people tell me that this stance is shallow and inappropriately judgmental. Is it? When we meet someone for the first time, we immediately assemble a collection of thoughts and assumptions based on how they’re dressed. Actually, we do this with everyone we see on the street! Is that person neat and tidy or an unmade bed? Are they a traditionalist or a hipster? Are they saying, “look at me!” or “go away”? People tell me this stance is overly judgmental. Yes, it is. But how do we distinguish between the staff in a restaurant versus the diners? Hospital personnel versus patients? The guides in Central Park? Answer: their clothes.

While I appreciate, and even admire, people who regularly change their fashion according to whims and impulses (my beloved Heidi Klum is one), I sincerely believe in the efficacy of a uniform; that is, clothing that you can effortlessly reach for in your closet, that looks good on you, makes you feel confident and won’t look dated in six months or a year. I personally subscribe to this belief, because, quite frankly, it’s easy.

The wonderful thing about fashion today is that you can be whoever you want to be. Gone are the decades of highly prescriptive dressing. So, consider the power of semiotics and think about how you want the world to perceive you.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

February 12, 2024

Gershwin’s “Rhapsody” at 100; Still Capturing the American Character

George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue,” a rapturous burst of music that has become a motif of the nation’s creative spirit, turns 100 today. It was first performed in New York on the snowy Tuesday afternoon of Feb. 12, 1924.

Commissioned and premiered by the popular conductor Paul Whiteman at a concert designed to showcase high-minded American musical innovations – with the 25-year-old Gershwin on piano – the concerto-like composition, mixing jazz and classical themes, eventually became synonymous with American musical flair and sophistication. In its various forms and orchestrations, it has been recorded thousands of times the world over, become a classical concert staple a theme song for an airline and was performed simultaneously by 84 pianists at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles.

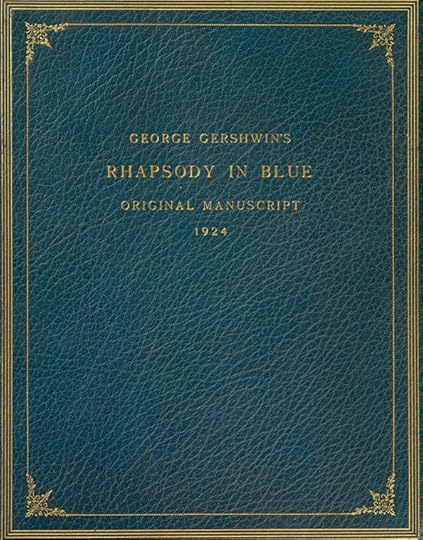

The Library is home to the George and Ira Gershwin Collection, including George’s piano and a leather-bound copy of his original manuscript of “Rhapsody.” We’re marking the centennial with several things, including an around-the-nation video tribute that highlights the piece’s continuing role in musical education, performance and spectacle.

{mediaObjectId:'10F5C80290272696E0635D0C938C9004',playerSize:'mediumWide'}“It’s one of the most recognizable pieces of music,” said Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress. “When you hear the first few notes you can’t help but start humming the rest.”

There’s a sold-out concert tonight at the Library featuring “Rhapsody” as the finale, to be performed by the U.S. Air Force Band with special guest pianist Simone Dinnerstein. The evening also features a lecture by Gershwin scholar Ryan Bañagale.

The video, meanwhile, features more than 20 performers from New York to Los Angeles to Seattle. There are stops in music havens such as Nashville and New Orleans, as well as unlikely locations, such as a Baltimore Ravens practice facility and the caverns of Luray, Virginia.

“The project shows how ‘Rhapsody’ and the rest of the Gershwins’ music is for everyone,” said Hayden. “You can enjoy their music in a grand symphony hall, in the classroom, in a parade, the practice field or while tapping your feet in the sand.”

Justin Tucker, the Ravens’ placekicker, is not only the most accurate kicker in National Football League history, but can also sing operatically in seven languages. (He graduated from the Sarah and Ernest Butler School of Music at the University of Texas.) For him, humming “Rhapsody” while practicing was a natural. Béla Fleck, the 17-time Grammy winning banjo player, soared through Gershwin’s most difficult progressions; he’s just released a new album that features “Rhapsody” in three different variations.

The cover of Gershwin’s manuscript copy of “Rhapsody in Blue,” dated Jan. 7, 1924.

The cover of Gershwin’s manuscript copy of “Rhapsody in Blue,” dated Jan. 7, 1924.Gonzalo Rubalcaba, the Cuban-born jazz pianist and composer, turns in a virtuoso performance from Florida while Kat Meoz, a singer-songwriter-composer, gives us a take from California. That’s Otto Pebworth playing the Great Stalacpipe Organ in Luray Caverns; the School Without Walls Orchestra, the Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington, D.C.,and international whistling champion Chris Ullman from the nation’s capital; the Arrowhead Jazz Band and the New Orleans Baby Doll Ladies from the Crescent City; the Nashville Symphony Orchestra and country/pop singer Nick Fabian from Music City; tap dancer and choreographer Caleb Teicher from New York, along with many others. The animated caricature of Gershwin playing “Rhapsody” is from Disney’s “Fantasia 2000.”

The origin story of “Rhapsody” is well known. Whiteman, the most popular jazz conductor of his day (though hiring only white musicians), commissioned the young Gershwin to write a composition that could show off American originality with classical sophistication. Gershwin, reluctant to take the assignment, only had about six weeks to put it together, while still keeping up his work on Broadway musicals.

The Library’s manuscript copy of his work is in pencil, with his block lettering spelling out “RHAPSODY IN BLUE – FOR JAZZ BAND AND PIANO” atop the first page. It’s dated Jan. 7, 1924, a few days into the assignment. He was greatly aided by Ferde Grofé, who arranged the score. The first performance, at a packed house at Aeolian Hall, drew mixed reviews from critics, though it was popular with the crowd.

You can hear an early recording on the Library’s National Jukebox from 1924 by Whiteman’s orchestra with Gershwin on the piano. Recording limitations of the time forced the nine-minute piece to be recorded in two sections, with the second part here.

So identified was Gershwin with the Jazz Age that when he died in 1937 at the age of 38 (a brain tumor), the New York Times obituary identified him along with “The Great Gatsby” author F. Scott Fitzgerald as a “child of the Twenties.”

“What he wanted to do most, he said, was to interpret the soul of the American people,” the Times wrote.

Ferde Grofé, the arranger of much of “Rhapsody.” Photo: Bain News Service. Prints and Photographs Division.

Ferde Grofé, the arranger of much of “Rhapsody.” Photo: Bain News Service. Prints and Photographs Division.One of the curious things about “Rhapsody” has been its elasticity. There a short versions and long versions and pieces for solo piano and full orchestras and everything in between. Leonard Bernstein, arguably the most famous American conductor of the 20th century, loved “Rhapsody” but famously noted that it had such a loose structure that you could leave out or rearrange segments and the piece would still work. Leonard Bernstein, “Why Don’t You Run Upstairs and Write a Nice Gershwin Tune?” in The Joy of Music (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1959), 52–62.

The Library also has the papers of Grofé, who also arranged the 1942 orchestral version of “Rhapsody” that almost immediately became the standard rendition and the one you likely think of today when the song comes to mind. Taken together, the Grofé and Gershwin collections give the Library all three manuscripts of “Rhapsody” that led up to its historic debut.

The nation is a far different place today than it was in 1924, but it’s part of the song’s famous elasticity, part of its peculiar magic, that enables it to still speak so eloquently, so broadly, to the national character.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers