Library of Congress's Blog, page 12

August 20, 2024

Annalee Newitz and “Weaponized Stories” at the National Book Festival

Stories can be a lot of things, as journalist and novelist Annalee Newitz writes in “Stories Are Weapons,” but in the end they are powerful instruments that can be used for good or evil, to comfort the afflicted or afflict the comfortable.

“The thing about stories is that they are emotional and oftentimes appeal to us on a personal level in a way that is very difficult for facts to do,” she said in a recent phone conversation. “They get used as a great system of conveying information within an emotional shell.”

The subtitle of her 2024 book is “Psychological Warfare and the American Mind,” and she’ll be discussing the subject with British author and journalist Peter Pomerantsev, whose “How to Win an Information War: The Propagandist Who Outwitted Hitler” also came out this year. The two will present “Words at War: Misinformation Then and Now” at the Library’s National Book Festival in D.C. on Saturday, Aug. 24.

Both writers have a modern take on the issue — social media platforms continue to spread disinformation campaigns at lightning speed around the planet, infusing international conflicts and domestic cultural debates with a kinetic, off-balance energy.

“Methods of information warfare that seemed novel in 2016 are now part of our everyday lives,” Newitz, who uses they/them pronouns, writes. The nation has entered a period of “chaotic” terrorism, they observe, when campaigns on social media are designed to trigger someone into violence, but it’s impossible to predict who, when or where or exactly why.

Still, both writers acknowledge that this is a very new wrinkle in a very old game.

“All warfare is based on deception” is one of the most famous passages of “The Art of War,” the Chinese classic attributed to Sun Tzu about 2,400 years ago. Confusing your enemy about where, when and how you’ll attack is essential.

After the warfare is over, conquering nations have always written narratives that portray them as heroes, with their defeated foes as anything from misled enemies to barbaric hordes. They do not, of course, portray themselves as simply more ruthless, better armed and better organized combatants who got lucky on a particular day.

Instead, they create narratives — stories — that they or their cause has been ordained for power by a supernatural deity, or they are higher forms of human beings. These stories become the foundational myths, and very real cornerstones, of societies and civilizations.

Newitz, 55, who writes both science fiction and nonfiction, takes their story of American military psychological operations (“psyops”) from the 19th century forward. “Though World War I was the first time that psychological war was identified as such, the practice of combining propaganda and mythmaking with total war began with the Indian Wars.”

Pomerantsev, who was born in Ukraine and has written several books on propaganda (particularly of the Soviet variety) writes from more of an international perspective.

What’s striking to Newitz is that the American military’s techniques, once deployed at foreign targets, are now being used by domestic political and cultural groups against one another. American psyops moved into official existence in the late 1940s when an intelligence officer named Paul Linebarger wrote a manual called “Psychological Warfare” for the U.S. Army that became so influential that it is still used today.

Newitz observes that Linebarger also wrote science fiction under a pen name and was quite accomplished at “worldbuilding,” or creating a fictional universe that seems complete unto itself.

“The more I immersed myself in Linebarger’s work,” Newitz writes, “the more obvious it became that his skill as a science fiction writer was a crucial part of his success with military psyops. … Linebarger believed that words, properly deployed, were more powerful than bombs.”

Further propelled by the powers of advertising, with its calls to action in a few words or images, such psyops or disinformation campaigns gained new power as they blurred the lines between reality and fiction. In this way, Newitz says, current cultural warfare uses a troika of elements to wage disinformation: scapegoating, deception and threats of violence.

“These weapons are what separate an open, democratic public debate from a psychological attack,” they write.

Still, stories can also be used for greater inclusion and more open societies. Psychologist William Moulton Marston created Wonder Woman for DC Comics in 1941 as “psychological propaganda for the new type of woman.”

The superhero story of Diana Prince was perceived as action-based comic book heroine, not crude propaganda. Still, from Marston’s perspective, his campaign worked beyond his wildest dreams. Today, the character is a pop culture staple.

There are other positive campaigns, Newitz writes, such as the Southwest Oregon Research Project, which shows that local Native Americans did not disappear, as government authorities had long insisted, and that they were still part of the community.

Still, those battles are never fully won, Newitz writes, and won’t be over anytime soon: “… the culture wars over who counts as an American, or even as a human being, are far from over. They return, like repressed memories, to retraumatize us.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 15, 2024

Gregory Lukow, Library’s Film Preservation Leader, Retires

Gregory Lukow, chief of the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center, retired July 31. He tells us about his career and future plans.

Tell us about your background.

Born and raised on a farm in Nebraska, I studied broadcast journalism and English as an undergraduate at the University of Nebraska. My college jobs included photochemical processing of 16 mm news film I and my fellow students shot in the J school. I also disc jockeyed for the university radio station and the then most-powerful FM station in Nebraska, KFMQ. My English degree was achieved primarily by taking all the film courses that department offered.

Knowing farm life wasn’t for me, I moved to Los Angeles in 1975 and applied for grad school at UCLA. Happily, I was accepted. I obtained graduate degrees in film and television studies. My first experience with archival film programming was a founder of the student-run UCLA Cinematheque in 1979 showcasing prints from the UCLA Film & Television Archive.

In 1984, I began working at the American Film Institute’s National Center for Film and Video Preservation. I was there 14 years, the last five as director. I’m proud to have been a principal founder of the Association of Moving Image Archivists, in 1991, and to have served five terms as the association’s first elected secretary.

What brought you to the Library?

In 1998, the American Film Institute abolished the NCFVP, and for the next two years I worked at the UCLA Film & Television Archive. My primary responsibility there was to establish UCLA’s Moving Image Archive Studies program — the first such graduate degree offered in the U.S.

In 2000, I was hired as assistant chief in the Library’s Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division by division Chief David Francis. My first days on the job, in January 2001, were spent in Dayton, Ohio, where I stopped on my cross-country drive from Los Angeles to D.C. to meet the Film Lab and Nitrate Vault staff at the Library’s Motion Picture Conservation Center.

Francis retired in February 2001, and I served as de facto head of MBRS under acting Chief Diane Kresh, the director of Collections Services, just as the design of what was to become the Packard Campus was getting underway. In 2003, the Library conducted its search for a new chief, and I was immensely gratified to be selected.

What achievements are you most proud of?

Certainly, my first seven years when I was the Library’s lead representative in overseeing the design and construction of the Packard Campus, guiding one of the Library’s most advanced technological undertakings to its opening in 2007.

It was an extraordinary privilege to create a new national audiovisual archive and library as close as possible to the ideal while working with the architects and design engineers that David Packard’s Packard Humanities Institute (PHI) brought to the table and with individuals at the Architect of the Capitol and the Library, including the NAVCC staff. That yearslong effort was by far the most educational, challenging and fulfilling experience of my professional life.

What are some standout moments?

The July 2007 ceremony conveying the completed Packard Campus from PHI to the Library — with numerous members of Congress present — was the capstone moment of those first seven years. Also, the opportunity in 2014 to testify before the House Judiciary Committee on NAVCC’s work and copyright issues important to audiovisual preservation and access.

The live concerts we presented at Packard were immensely enjoyable: We hosted members of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame (Roger McGuinn of the Byrds), the Country Music Hall of Fame (Connie Smith, accompanied by husband Marty Stuart) and the Songwriters Hall of Fame (Jimmy Webb).

Finally, last year’s inaugural Library of Congress Festival of Film & Sound was a fantastic opportunity to showcase the Library’s audiovisual preservation work, and the four-day festival marked the peak movie-going experience of my 24 years at the Library.

What’s next for you?

My wife, Rachel, and I won’t be leaving Culpeper soon. We’ve got a lot of downsizing to do, including preparing a range of collection materials I hope to donate to the Library.

My main retirement project will be organizing my photograph collection. In 1988, I started photographing old and surviving movie palaces and theaters around the world. In doing so, I began “collecting” U.S. highways and back roads, and I look forward to taking many more road trips with Rachel and adding more theaters to the collection. Thus far, I’ve photographed over 3,800 theaters. Over half of them were shot on 35 mm film between 1988 and 2003, so one of my main retirement projects will be to digitize those negatives.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 13, 2024

The (Newly Revealed) Wonders of a 16th Century Portolan Chart of the North American Coast

It’s not often that the Library has a chance to acquire a portolan chart — an early nautical map, hand drawn on animal skin, that explorers used to navigate the seas. Not many still exist, so the Library leaped at the chance last fall to acquire a circa 1560 portolan depicting the North American East Coast by Portuguese cartographer Bartolomeu Velho.

Extending from the coastline of what is now Texas, around the Gulf of Mexico to Florida then up the entire present-day East Coast, the original map and a high-resolution enhanced version, produced by the Preservation Research and Testing Division, are now on the Library’s website. The latter reveals previously illegible place names — including some of the earliest known uses of names by European explorers for locations on the Atlantic coast. The enhanced map, producing by multispectral imaging, illuminates things that the human eye cannot see. It’s the first time the Library has posted a PRTD-enhanced image.

“It’s exciting,” Fenella France, PRTD’s chief, said of the web availability of the image. “It is now a resource for scholars from anywhere.”

It required coordination between two Library’s divisions — Geography and Map and PRTD. PRTD’s work, said G&M cartographic acquisitions specialist Robert Morris, “added even more value to what was already a valuable chart.”

For more than 15 years, PRTD has used noninvasive techniques, chief among them multispectral imaging, to glean information from Library collection items that the human eye cannot see. Multispectral imaging involves digitally photographing an object at multiple wavelengths. Through imaging and subsequent processing of the data it generates, PRTD can obtain information about inks or colorants used in an object, for example, or detect a watermark that helps to date it. In some cases, an ink may almost melt away, revealing another ink below.

“It provides more information than our eyes can perceive because the camera can see in ultraviolet, and the camera can see in infrared,” said Meghan Hill, a PRTD preservation science specialist.

A close-up of the Velho portolan chart that reveals place names by using multispectral technology. Photo: Preservation Research and Testing Division.

A close-up of the Velho portolan chart that reveals place names by using multispectral technology. Photo: Preservation Research and Testing Division.Most famously, multispectral imaging at the Library confirmed in 2010 that Thomas Jefferson scrawled the word “citizens” over “subjects” in the rough draft of the Declaration of Independence to describe the people of the fledgling United States.

In the years since, PRTD has imaged hundreds of Library holdings using increasingly sophisticated instruments and techniques.

In this case, Morris asked PRTD to examine it in advance of purchase — PRTD often images prospective acquisitions to confirm (or not) that they coincide with the information vendors provide.

“I asked PRTD to verify that nothing was anomalous for a mid-16th-century chart,” Morris explained. “If there had been inks, for example, not used during the period, it might indicate doctoring.”

PRTD found nothing inconsistent with the vendor’s description but noted extreme fading of iron gall ink on certain areas. PRTD agreed, should G&M purchase the portolan, to do further processing of imaging data to enhance details. Morris was particularly interested in the place names along the coast, many too faded to discern.

Typical of charts of its kind, the portolan features toponyms, or place names, set at an almost perpendicular angle to the coast and limited geographical detail beyond the coast.

Once G&M purchased the chart, PRTD initiated in-depth analysis.

“The actual imaging might take a day,” France said. “It’s the processing to pull out the information that can take a couple of weeks or longer.”

Using specialized software, PRTD applies different hues, called false colors, to different components in an object and brings forward certain components while diminishing others. The team draws on techniques that complement multispectral imaging — infrared, reflectance and the X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy.

Infrared analysis provides data about the substrate of an item — parchment, for example — while reflectance spectroscopy gives rise to details about color components within the visible spectrum, including plant-based materials. X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy offers information about trace metals in pigments, such as copper, iron or mercury.

“Essentially, what we’re doing is using different types of light to identify materials,” Hill said.

These techniques showed not only place names that had been illegible, but a scale, numbers and flags of European claimants to regions.

“Processing made them pop out more, made the details more visible,” Hill said.

Scholars mine such details, Morris said. “Place names, for example, can be used for dating,” he explained. “And when they are referenced beyond cartography, they can verify that people were at a certain location.”

The Velho portolan made its way to the Library by way of a circuitous route, to say the least.

It was found in 1961 — roughly 400 years after its creation — at Rye Castle Museum in Sussex, England. By then, however, the entire chart was no longer intact, having been cut into quarters and repurposed for its vellum, or animal skin.

The segment the Library purchased — the upper-left quadrant — was used to bind a 17th-century English manuscript before being identified as a portolan and separated from the book, according to Portuguese cartography experts Armando Cortesão and Avelino Teixerada Mota.

The Rye Castle Museum holds another quadrant of the chart. The two others “appear to be lost to mankind,” Morris said.

When the Philip Lee Phillips Society, G&M’s donor group, heard that the Library was considering purchasing the portolan last year, the society’s board quickly voted to contribute, Morris said.

Already, scholars are researching the chart, drawing on the rich details PRTD uncovered. Morris knows of at least one major article scheduled to publish within the year.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 8, 2024

Kwame Anthony Appiah Awarded Kluge Prize

This is guest post by the Office of Communications media relations team.

Kwame Anthony Appiah, the internationally recognized philosopher, scholar and author, will receive the 2024 John W. Kluge Prize for Achievement in the Study of Humanity, Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden announced today. The prize recognizes individuals whose outstanding scholarship in the humanities and social sciences has shaped public affairs and civil society.

Appiah is the Silver professor of philosophy and law at New York University. He is internationally recognized for his contributions to the study of philosophy as it relates to ethics, language, nationality and race.

Appiah also writes “The Ethicist” in The New York Times Magazine, a column and newsletter that explores ethical approaches to solving interpersonal problems and moral dilemmas.

“Dr. Appiah’s philosophical work is elegant, groundbreaking and highly respected,” Hayden said. “His writing about race and identity transcends predictable categories and encourages dialogue across traditional divisions. He is an ideal recipient for the 2024 Kluge Prize, and we were thrilled to select him for this award.”

The Library is developing programming on the theme of “Thinking Together” that will showcase Appiah’s work for a public audience.

Appiah earned a Bachelor of Arts degree and a doctorate from Cambridge University. Over the years, he has taught at Yale, Cornell, Duke, Harvard and Princeton universities.

He is the author of more than a dozen books, including academic studies of the philosophy of language, a textbook introduction to contemporary philosophy and “In My Father’s House: Africa in the Philosophy of Culture,” considered a canonical work in contemporary Africana studies.

Since the 1990s, Appiah’s work has been widely regarded as having deepened the understanding of ideas around identity and belonging, concepts that remain deeply consequential.

Debra Satz, who served on the Library’s Scholars Council, called Appiah a “giant who influenced the academy and beyond.”

Satz is the Vernon R. and Lysbeth Warren Anderson dean of the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford University and the Marta Sutton Weeks professor of ethics in society.

“His work is of unusually broad scope, ranging from technical work in the philosophy of language to core ethical issues about identity to questions of the value of work,” Satz said. “What unites his writings on all of these diverse topics is a consistent wide-ranging humanity and a courageous refusal to fit his views into any narrow boxes.”

Scholars Council member Martha Jones, the Society of Black Alumni presidential professor and professor of history at Johns Hopkins University, said Appiah’s work is of “tremendous breadth of interest, expertise and engagement, from scholarly to serious popular writing.”

“Kwame Anthony Appiah moves effortlessly between academic and public discussions on difficult topics, such as race, identity, privilege and power,” said Timothy Frye, the Marshall D. Shulman professor of post-Soviet foreign policy at Columbia University and Scholars Council member. “His academic work is rooted in philosophy, but the range of topics that he has addressed in his research and public writing is astonishing.”

Frye further noted that that “while many scholars are satisfied probing hard and important questions without taking the next step of offering guidance for how to solve them, Appiah is unafraid to offer solutions that recognize the complexity of the problems under study.”

Other books by Appiah include “The Ethics of Identity,” “Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers,” “Experiments in Ethics,” “The Honor Code: How Moral Revolutions Happen,” “Lines of Descent: W.E.B. Du Bois and the Emergence of Identity,” “As If: Idealization and Ideals,” and “The Lies That Bind: Rethinking Identity.” He was coauthor of “Color Conscious: The Political Morality of Race” with Amy Gutmann.

Appiah has also co-edited volumes with Henry Louis Gates Jr., including “Africana: The Encyclopedia of African and African-American Experience.”

Appiah is the current president of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He has served as president of the PEN America Center, as a member of the advisory board of the National Museum for African Art, as chair of the board of the American Council of Learned Societies and as president of the Modern Language Association and of the Eastern Division of the American Philosophical Association.

Awarded every two years, the Kluge Prize highlights the value of researchers who communicate beyond the scholarly community and have had a major impact on social and political issues. The prize comes with a $500,000 award.

Appiah joins a prestigious group of past prizewinners, including, most recently, historian George Chauncey, a trailblazer in the study of American LGBTQ+ history; Danielle Allen, renowned scholar of justice, citizenship and democracy; and historian Drew Gilpin Faust, former president of Harvard University.

Hayden selected Appiah from a short list of finalists following a request for nominations from scholars and leaders all over the world and a three-stage review process by experts in and outside of the Library.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 6, 2024

Eliot’s Bible

This is a guest blog by María Peña, a writer-editor in the Office of Communications. It also appears in the July-August issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

After arriving in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1631, English Puritan minister John Eliot made history not only with his steadfast mission to convert Native Americans to Christianity but also for his evangelical method: translating the Bible into the Wampanoag language of the region’s Algonquin tribes.

Eliot believed Indigenous communities would be more receptive to the message of Christianity if the holy scriptures were written in their language, also known as Natick. He learned the previously unwritten language and spent years translating the Geneva Bible into it, getting significant help from Native Americans such as James Printer and John Nesutan, according to the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Printed in Cambridge between 1660 and 1663, the Eliot Indian Bible today represents a landmark in printing history: It was the first Bible printed in North America in any language.

Eliot was a pivotal figure among the Puritans. He helped settle the intertribal communities of Christian converts, called “praying towns,” that dotted the New England landscape between 1646 and 1675. The establishment of these communities — 14 in total — was part of an attempt to impose Puritan rules, mores and lifestyles on recent Indigenous converts.

Eliot’s efforts to convert more Native Americans ultimately failed, in part because of bubbling animosity between white Colonists and the Wampanoags. And most copies of his Bible were destroyed during King Philip’s War (1675-1676), a conflict that took a toll on the region’s Indigenous population. A second edition of the Eliot Bible was published in 1685 — the edition held by the Library today.

In recent decades, the Wampanoag nation has used the Eliot Bible as a tool to help resurrect its ancestral language, which declined soon after the Mayflower Pilgrims arrived and went extinct in the 19th century.

Founded by MIT-trained linguist Jessie Little Doe Baird in 1993, the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project uses the Eliot Bible and archival records to bring the language back to Wampanoag households, one student at a time.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 2, 2024

My Job: Karen Werth

Karen Werth is deputy chief of the Exhibitions Office.

Tell us about your background.

I grew up in the Washington, D.C., metro area and earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts in sculpture from Winthrop University and a Master of Fine Arts in jewelry design and metalsmithing from the University of Michigan.

As a student, I volunteered in galleries at both of my universities. While serving as an adjunct professor at Winthrop University, it became apparent to me that the museum profession was a viable and exciting direction.

My journey took me first to the National Museum of Women in the Arts, where I served as exhibit designer, then to the University of Maryland, where I created and taught undergraduate courses in museum studies in addition to designing and producing exhibits.

Later, I served as project manager for museum exhibit fabricators and design firms, overseeing the design and production of high-profile, large-scale, multimillion dollar projects for cultural institutions across the country.

What brought you to the Library, and what do you do?

I joined the Exhibits Office in 2011 as a production officer, charged with managing procurement and production for the Library’s exhibits and displays.

In 2018, I was promoted to deputy chief of exhibitions. Now, in addition to overseeing the production of exhibitions, I actively participate in planning, budgeting, design development and procurement for them.

What are some of your standout projects?

I have had the privilege of working on many exceptional projects at the Library, including the Magna Carta exhibit, “Baseball Americana” and the Rosa Parks exhibit, to name a few. But the recent Treasures Gallery opening has been one of my more challenging and exciting adventures.

It required countless hours of planning, collaborating and creative problem solving involving the Exhibits Office, the exhibit design firm, an exhibit fabricator and stakeholders from across the Library in partnership with the U.S. Capitol Police and the Architect of the Capitol.

The final design features monumental and elegant glass display cases that allow visitors to experience the Library’s collections from many perspectives.

One of the greatest challenges for this project was getting these large glass cases into the Jefferson Building. They had to be carefully craned into the building in sections through a second-floor balcony door, an effort that took many weeks to coordinate and two full days to complete.

After the delivery, the project team spent several weeks assembling casework and installing collections, graphics and audiovisual components to create a magical and engaging exhibit experience — one that I hope will captivate visitors!

What do you enjoy doing outside of work?

I am an accomplished fine craft artist. Since 2010, I’ve created fused glasswork that I display and sell at craft shows and festivals around the region. I continue to explore new techniques and processes and occasionally attend workshops and artist residencies at places such as the Corning Museum of Glass in Corning, New York, and Penland School of Craft in Ashville, North Carolina.

What is something your co-workers may not know about you?

I have been an active member of the Capital Rowing Club since 1996, and I row out of the Anacostia Community Boathouse. I learned to row with Capital and competed as a master rower for 12 years, winning gold on a regional, national and international level. I’ve since retired from competition, though I still row for fun and exercise.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 31, 2024

William Crogman’s Daring “Race Textbook” of 1898

This is a guest post by Jordan Ross, a Junior Fellow in the Office of Communications this summer.

At the end of the 19th century, William Henry Crogman dared to think of a revolutionary idea: a textbook on African American history, achievements and survival for Black students both in and outside of the classroom.

Textbooks for Black children were rare and oftentimes impossible to develop in the era. Reconstruction had ended two decades earlier. “Black Code” laws targeted African Americans for police harassment and abuse. Racialized policies such as the 1896 Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson mandated separate-but-equal facilities in public accommodations, effectively legalizing segregation. And instead of “equal” funding, legislatures spent little on educating Black children.

But Crogman’s 1897 “Progress of a Race; or, The Remarkable Advancement of the Afro-American Negro from the Bondage of Slavery, Ignorance and Poverty to the Freedom of Citizenship, Intelligence, Affluence, Honor and Trust,” written with fellow educator H.F. Kletzing, sought to fight that bigotry. (The link above is to a later, digitized edition with several editorial changes, including the title and co-author.)

It told the history of Black Americans as a heroic quest against overwhelming odds. It was advertised with tantalizing taglines such as “the information contained in this book will never appear in school histories.”

“Springing from the darkest depths of slavery and sorrowful ignorance to the heights of manhood and power almost at one bound, the Negro furnishes an unparalleled example of possibility,” wrote Booker T. Washington in the introduction. Washington’s intellectual rival in the era, W.E.B. Du Bois, also praised the book.

In this history, “Slavery” was just one chapter, while others dealt with the “History of the Race,” “The Negro in the Revolution,” “Anti-Slavery Agitation,” “Moral and Social Advancement,” “Club Movement Among Negro Women,” “Financial Growth” and so on.

The authors also portrayed it as a bold new step: “… to our knowledge there has been no attempt made to put into permanent form a record of his [Black peoples’] remarkable progress under freedom — a progress not equaled in the annals of history,” they wrote.

Containing over 600 pages with zinc engravings and beautiful pictures, the textbook caught on quickly, was heavily circulated and sold door-to-door through subscription for decades. A copy of the 1898 original textbook is preserved at the Library and a later edition is digitized.

Shortly after its publication, Daniel Alexander Payne Murray, one of the Library’s assistant librarians, had the foresight to include it on his list of books by Black Americans at Du Bois’ seminal exhibit the 1900 Paris Exposition, “The Exhibit of American Negroes.”

Murray’s bibliography, “Preliminary List of Books and Pamphlets by Negro Authors,” was not the first of its kind but probably the most influential. It included books on the emerging genre that Crogman’s “Progress” exemplified, often called “race textbooks” or what literary scholar Elizabeth McHenry has coined “racial schoolbooks.” These textbooks were subscription-based primers on African American history and progress throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Largely forgotten now, these textbooks were daring and innovative, drawing praise from across Black intelligentsia. These predated Carter G. Woodson’s 1922 landmark “The Negro in Our History” and contributed to the celebration of Black history almost three decades before Negro History Week debuted in 1926.

Who was Crogman, and how did he come to write such an influential work?

He was born free in 1841 on the small Caribbean island of St. Martin and was orphaned at age 12. He was mentored by an American sailor, though, and traveled with him as a seaman through various ports in South America, Europe and Asia.

Intellectually curious, he saved money during these voyages and enrolled at Pierce Academy in Middleborough, Massachusetts. He quickly completed his studies and then enrolled in the classical course program at Atlanta University in Atlanta. Again, he was a dedicated and talented student, completing his studies in three years instead of four and was a member of the university’s first graduating college class.

Now armed with his bachelor’s degree, Crogman became one of the first faculty members of another famous Atlanta institution — Clark University. He became the university’s first African American president. (The two institutions later consolidated to form Clark Atlanta University.)

An aerial view of the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia. Designer: W.L. Stoddart. Prints and Photographs Division.

An aerial view of the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia. Designer: W.L. Stoddart. Prints and Photographs Division.Crogman’s academic passion was not only in the classroom but also in the wider public sphere.

In 1895, he and 14 other African American men developed a Negro exhibit for the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta. The exhibit, centered around the 25,000-square-foot Negro Building at the fair, displayed different forms of African American life throughout the South and highlighted their intellectual achievements. Scholars think it likely that Crogman was inspired by this exhibit and decided to put these experiences into a textbook – “Progress of a Race.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 25, 2024

Einstein’s Love Affair at Princeton

This is a guest post by Rachel McNellis, an archivist in the Manuscript Division and Josh Levy, a historian in the same division. It also appears in the July-August issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

In 1945, Margarita Konenkova was returning to Russia with her homesick husband, sculptor Sergey Konenkov. Before she left, she entrusted her New York neighbor with six letters received from Albert Einstein during their passionate affair. The neighbor left instructions that in case of her death, the letters be “burned without further ado.”

The letters were never burned. Instead, they ended up in the Library of Congress, closed to researchers until 2019.

Einstein, clearly infatuated, penned the letters between 1944 and 1945. One includes a sketch of a “Half-Nest,” a cozy room that resembles his home study. Though the sketch is simple, Einstein clarifies, he was not drunk when drawing it. He simply wished to capture the space he most associated with Konenkova.

The letters mix Einstein’s humanity with his genius. We see him incapacitated by illness, grounding his sailboat in stormy weather, railing against birthday parties as “stupid bourgeois affairs” but attending them anyway and smoking pipes that Konenkova sent him.

Then he becomes the renowned physicist again, debating Robert Oppenheimer, Bertrand Russell, Wolfgang Pauli and Kurt Gödel in his home. Occasionally, politics emerge. “I admire Stalin’s sagacity,” Einstein declares, without context. “He does it significantly better than the others, not only militarily but also politically.” He worries over nuclear secrecy and calls the growing alienation between Russians and Russian-Americans “a kind of personal expatriation.”

The affair was, of course, a secret. While Einstein was a widower, Konenkova remained married. Still, their friends were discreet. When asked later whether an affair had occurred, one only offered, “I certainly hope so! They were two lonely people.”

In 1994, a Russian newspaper finally revealed the affair. Later, Sotheby’s, having read the discredited memoir of an ex-Soviet spymaster, announced that Konenkova had been a spy, pressing Einstein for intelligence about the bomb. Several historians have since declared the claim implausible.

Of course, these letters contain no evidence that Konenkova really was a spy. But they do shed a little light on a clandestine encounter between two lonely people.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 24, 2024

Du Bois and the Paris Exposition of 1900: Three Pictures

This is a guest post by Lauryn Gilliam, a Junior Fellow in the Office of Communications.

The Paris Exposition of 1900 was an influential world’s fair devoted to technological achievements of the age, with awe-inducing buildings such as the Palace of Electricity, the Water Castle and the Grand Palais. But one of its most lasting contributions to international culture was simply called The Exhibit of American Negroes.

That display, composed of hundreds of photographs, charts, books, maps and diagrams, was organized by W.E.B. Du Bois, the writer, activist and sociologist; Thomas Calloway, a lawyer and activist; and Daniel A.P. Murray, an assistant librarian at the Library of Congress. They wanted to show the world — or at least the international visitors to the fair — that three decades and change after gaining their freedom, Black Americans were making vast intellectual and social gains. Their exhibit, within the Palace of Social Economy and Congresses, was to advocate for the preservation and positive representation of Black Americans, their literature, culture and history.

Du Bois curated some 550 photographs (click on blue “View all” hyperlink to see the thumbnails) into albums showing the diverse lives, patterns and personalities of African Americans, an important collection that is now preserved at the Library. There were formal portraits, snapshots, pictures of homes and streets and businesses. His intent with the photographs, as with the rest of the exhibit, was to combat the racist, stereotypical caricatures and scientific “evidence” that were being used to marginalize and discriminate against Black Americans.

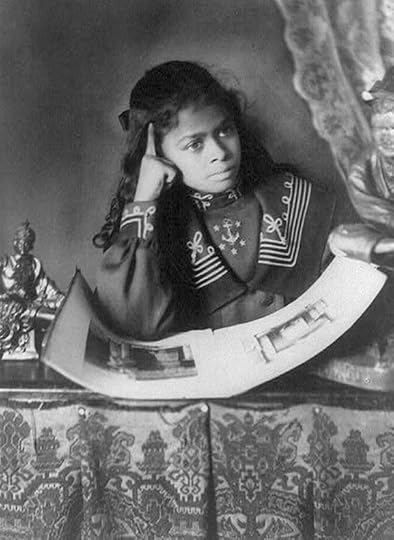

Here are portraits he selected of three unidentified Black women at three different stages of life — adolescent, adult and senior. In each, you’ll notice that the subjects are carefully dressed to exemplify the best qualities of their respective ages. Du Bois carefully curated the compositions.

A girl pictured in the 1900 Paris Exposition. Photo: Thomas E. Askew. Prints and Photographs Division.

A girl pictured in the 1900 Paris Exposition. Photo: Thomas E. Askew. Prints and Photographs Division.First, we have the promise of the future, a precocious girl reading a book or magazine. She’s in her Sunday best, seated at a desk covered in brocade and framed by small statues on her right and left. This is no barefoot waif running the streets, but a child of privilege, comfort and leisure. The elements of her pose — the gaze into middle distance, the serious expression, the hand and pointed finger at the side of her face — are clearly meant to show her in deep thought. This intelligence and critical thinking were qualities that most whites believed did not apply to Black adults in the era, much less to Black children. For Du Bois, who helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1909, these were the necessities upon which a new generation of Black achievement would be built.

In her youth and potential, the girl also embodies a symbol of freedom and new possibilities in a difficult era. The U.S. Supreme Court had ruled just four years earlier that “separate but equal” public accommodations were legal, thus solidifying segregation for generations. Further, it was not until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that racial discrimination in voting would be prohibited and Black people would gain meaningful access to the ballot. This child would have been in her 70s by then.

The privilege she displays here did know bounds; outside the photographer’s studio, she might have been educated but not considered worthy of white respect; admired for her intelligence but given a very limited universe in which to pursue it.

A young woman poses in fashionable clothes. Photo: Unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

A young woman poses in fashionable clothes. Photo: Unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.Next, we have a beautiful young woman dressed in upscale fashion. In many of the portraits in this collection, women appear in fancy clothing, no doubt to exhibit the finer qualities in life, to show them as wealthy and sophisticated. Again, this was to cut against the stereotypes of the era, in which Black women were portrayed as maids, cooks or as sex objects.

Here, the fancy headpiece, feathers and nice lace dress suggest Parisian fashions. She, too, is caught in a thoughtful pose, looking off camera. She leans into a style of idealized femininity, of the “New Woman” prototype that illustrator Charles Gibson used in his popular and influential drawings. The “Gibson Girl” was what smart society deemed a well-rounded woman — educated, socially polished and well-mannered. She strove to embody elegance and charm.

This is just what our unknown young lady portrays, but as a Black woman. In 1900, this was a bold new ideal in itself.

An unidentified woman featured in the Paris Exposition photo albums of Du Bois. Photo: Unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

An unidentified woman featured in the Paris Exposition photo albums of Du Bois. Photo: Unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.Finally, we have a dignified woman in her later years. Like our other two subjects, she’s dressed fashionably. But here, there’s a matronly presence to the outfit — the buttoned-to-the-neck dress, the close-worn cap and the long sleeves — all meant to show practicality, poise and stability. Elders are notably represented in this collection, suggesting Du Bois’ respect for the older generation that had survived so much. If we assume this woman is 60, then she would have lived more than a third of her life during slavery, seeing (and perhaps enduring) many of its horrors.

It’s worth noting that the photographer draws attention to her countenance by only pulling her face into full focus. The girl had a book and props, the young woman had her dress and jewelry, but here we are being directed only to the subject’s face. I see a strength and a caring nature there. One has to wonder: What did it mean to her to have her photo taken? What did her life look like?

Given that there are few surviving photographs of people who had been enslaved, this image, like so many in this collection, lingers in the mind.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 18, 2024

Gerrymandering: The Origin Story

—This is a guest post by Mark Dimunation, the former chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

The term for the political tactic of manipulating boundaries of electoral districts for unfair political advantage derives its name from a prominent 19th-century political figure — and from a mythological salamander.

The term, originally written as “Gerry-mander,” first was used on March 26, 1812, in the Boston Gazette — a reaction to the redrawing of Massachusetts state senate election districts under Gov. Elbridge Gerry.

Though the redistricting was done at the behest of his Democratic-Republican Party, it was Gerry who signed the bill in 1812. As a result, he received the dubious honor of attribution, along with its negative connotations.

Gerry, in fact, found the proposal “highly disagreeable.” He lost the next election, but the redistricting was a success: His party retained control of the legislature.

One of the remapped, contorted districts in the Boston area was said to resemble the shape of a mythological salamander. The newly drawn state senate district in Essex County was lampooned in cartoons as a strange winged dragon, clutching at the region.

The person who coined the term gerrymander never has been identified. The artist who drew the political cartoon, however, was Elkanah Tisdale, a Boston-based artist and engraver who had the skills to cut the blocks for the original cartoon.

Gerry was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, a two-term member of the House of Representatives, governor of Massachusetts and U.S. vice president under James Madison. His name, however, was forever negatively linked to this form of political powerbroking by the cartoon shown above, which often appeared with the term gerrymander.

The Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division holds the original print of the image, and the Geography and Map Division holds Tisdale’s original woodblocks — preserving the origins of a political practice that continues over two centuries later.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers