Library of Congress's Blog, page 13

July 15, 2024

The Blackwell Family Tree Is … My Family Tree

This is a guest post by Mila Hill, a junior fellow in the Office of Communications.

When I started my summer fellowship at the Library, I knew that it would be a catalyst for professional development — but I never expected to learn so much about myself and my family.

One night, while scrolling through my friends’ Instagram stories, I noticed one had reposted an incredible family tree that would soon be on display at the Library’s new Treasures Gallery. The tree’s size and artistry alone made me want to know more, but I soon saw that the tree documented the Blackwell family. Now I was especially intrigued.

Blackwell is a family name on my mom’s side. An even better clue was the presence of tennis legend Arthur Ashe’s name. My family has always known that Ashe is our cousin, so his name, inscribed on a gold-painted leaf, confirmed that this wasn’t just any Blackwell family from Virginia: It was ours.

My direct connections to the tree are Minnie Blackwell and Thomas Reese, my great-grandparents. Minnie and Thomas had two children, Willie and my grandmother Dorothy. I’ve always known Minnie’s name because I’m named after my great-grandmothers: Minnie, Ida, Lazelle and Audrey. Their first initials spell my name, Mila. After conferring with my mom and grandma, I knew to look for my great-grandfather Thomas Reese as well.

The Library has great scans of the tree, so from my tiny phone screen I was quickly able to find my great-grandfather Thomas above the Ashe branch of the tree; he is listed with his parents, Carrie and Edward Reese.

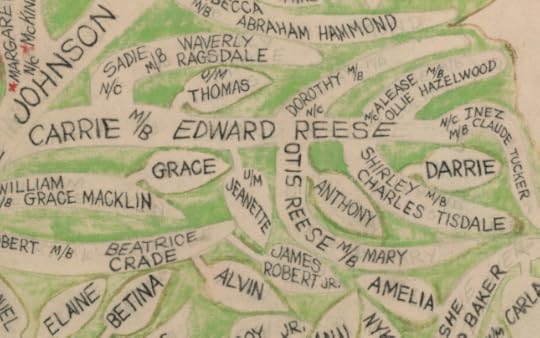

Carrie and Edward Reese on the Blackwell’s Kinfolk Family Tree with their son Thomas. Artist: Wilfred T. Washington. History and Genealogy Section.

Carrie and Edward Reese on the Blackwell’s Kinfolk Family Tree with their son Thomas. Artist: Wilfred T. Washington. History and Genealogy Section. Finding my family on the canvas was quite a shock. No one in my branch of the family knew of the tree’s existence, but we were all quick to embrace our newly discovered extended family. My mom has since reminded me that there can be only so many African American Blackwells in the Virginia countryside.

I was also emotional at the tangible connection that I’d been given to my family. The tree is accompanied by a book of family history going back to the 1730s. Knowing your ancestors’ names is one thing but seeing them on a piece of folk art, really knowing that they existed and mattered in the world, is entirely another.

To fully appreciate the tree, I think it’s necessary to appreciate Thelma Short Doswell, a renowned genealogist and my newfound cousin, who took on the massive project of making the tree. She did most of her research in the 1950s, when records could only be accessed in person at courthouses or at various record keepers across Virginia. She worked on this tree, and others made later with even more names, for more than 25 years. The tree is not just a memory of her life’s work but also of her life’s passion.

A mark of a good genealogist is the desire to understand the people beyond the names who are found in records. Thelma created the Blackwell’s Kinfolk Tree to show her family history using oral histories, slave records and other documents to get a fuller picture of the people whose names she found.

Thelma’s work and methods made me think harder about my ancestors and the lives they lived. I’ve always known that my family is descended from kidnapped, enslaved and displaced people. But it’s rare to know African American family history prior to 1865, when the Civil War ended and the 13th Amendment officially abolished slavery. Before then, enslaved families had been separated since they were forced onto slave ships, so much so it’s nearly impossible to track a family line back to their arrival in the United States. But because of Thelma’s incredible work, I know the names and stories of the women who created the Blackwell family.

Amar and her daughter Tab are those matriarchs. In 1735, Amar and Tab were among 188 Africans who sailed from the Gold Coast of Africa to the colony of Virginia. Upon their arrival, Amar and Tab were purchased in Yorktown, Virginia, and given the Blackwell surname.

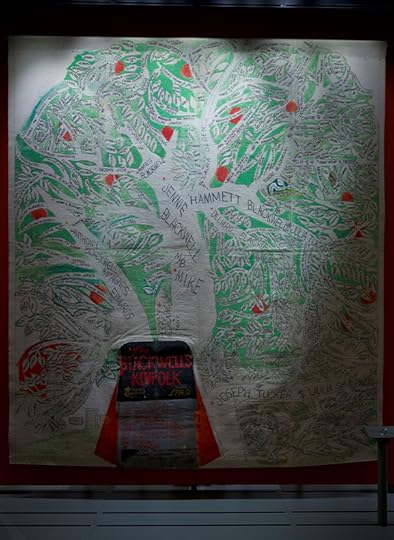

The Blackwell family tree exhibit in the Treasures Gallery. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The Blackwell family tree exhibit in the Treasures Gallery. Photo: Shawn Miller.Learning Amar and Tab’s names, seeing the tree in all of its glory, and sharing it with my immediate family has been an incredible experience. Before seeing the tree in person, I didn’t fully understand how impressive it was. Its sheer size (9 feet tall and 6 feet wide) was enough to make me emotional. Another personal touch: My family history is on display in a major cultural institution, alongside Stan Lee and Steve Ditko’s first Spider-Man comic, the item that made me want to be a librarian.

My family history is also hanging alongside so many important items from across the Library’s collections and across thousands of years of history. It’s enough to make me feel like I’m important too. Now that I know so much more about where I come from, I feel so much more certain of my place in the world.

My family is my favorite thing in the world and this summer, my favorite thing has grown exponentially.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 11, 2024

James McBride Awarded the 2024 Prize for American Fiction

Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden announced this week that the Library is conferring the 2024 Prize for American Fiction on acclaimed author James McBride. He will accept the prize at the National Book Festival on Aug. 24.

One of the Library’s most prestigious awards, the annual Prize for American Fiction honors a literary writer whose body of work is distinguished not only for its mastery of the art, but also for its originality of thought and imagination.

“I’m honored to bestow the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction on a writer as imaginative and knowing as James McBride,” Hayden said. “McBride knows the American soul deeply, reflecting our struggles and triumphs in his fiction, which so many readers have intimately connected with. I, also, am one of his enthusiastic readers.”

The award seeks to commend strong, unique, enduring voices that — throughout consistently accomplished careers — have told us something essential about the American experience.

“I wish my mom were still alive to know about this,” McBride said. “I’m delighted and honored. Does it mean I can use the Library? If so, I’m double thrilled.”

McBride is the author of the bestselling novel “Deacon King Kong”; “The Good Lord Bird,” winner of the 2013 National Book Award for Fiction; “The Color of Water”; “Song Yet Sung”; the story collection “Five-Carat Soul”; and the James Brown biography “Kill ’Em and Leave.”

His debut novel, “Miracle at St. Anna,” was turned into a 2008 film. In 2016, McBride was awarded the National Humanities Medal.

He is also a musician, a composer and a current distinguished writer-in-residence at New York University.

McBride’s most recent bestselling novel, “The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store,” received the 2023 Kirkus Prize for Fiction and was named Barnes and Noble’s 2023 Book of the Year.

The National Book Festival will take place from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in Washington, D.C. The theme is “Books Build Us Up.”

On Aug. 1, McBride will participate in a virtual interview with PBS Books as part of a series previewing 2024 festival authors.

McBride has appeared at multiple National Book Festivals in past years, most recently in 2020, when he spoke about his novel “Deacon King Kong.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 8, 2024

Folklorist Sidney Robertson and Her “California Gold”

Sidney Robertson was one of the trailblazing American women of the 1930s and 1940s, the kind of life you’d associate with Martha Gellhorn, Dorothea Lange or Zora Neale Hurston.

Born into a wealthy California family (that lost its money in the 1929 stock market crash), she traveled Europe as a teen, spoke four languages, graduated from Stanford and played classical piano. She was a friend of John Steinbeck, took classes from Carl Jung and created a landmark folk music project. She got married and divorced. Working for various New Deal programs, she drove more than 300,000 miles crisscrossing 17 states while lugging hundreds of pounds of recording equipment, most of those miles alone with her dog and a sleeping bag.

All this before 40, all this before marrying the influential and innovative composer Henry Cowell and devoting the second half of her life to his career, when she became known as Sidney Robertson Cowell.

Her escapades and groundbreaking work is captured in “California Gold: Sidney Robertson and the WPA California Folk Music Project,” a new book by Catherine Hiebert Kerst, a former Library archivist who worked for years to catalogue and preserve Robertson’s work. It’s published by the University of California Press in association with the Library.

“It was so exciting to me because I had never heard of this woman’s work,” Kerst said in a recent interview, describing the moment in 1989 when she began work on the collection. “She was still alive when I started, living in upstate New York, and we corresponded back and forth. Her eyesight was going but she was still very sharp and that was incredibly helpful.”

The music Robertson collected while directing the California Folk Music Project from 1938 to 1940 for the Works Progress Administration is some 35 hours in 12 languages by 185 musicians. (The agency was renamed the Work Projects Administration during her tenure.) Her staff included nearly two dozen people, and they recorded in mostly the northern part of the state. They recorded Spanish and Portuguese settlers who had been there for ages and more recent immigrants from Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Hungary, Russia and others. She also recorded Dust Bowl migrants from the Midwest. The songs could be classified as sea shanties, fiddle dance music, communal singing or bawdy version of bar songs.

It was colorful work – she once heard a “horribly inflated pig used as a bagpipes by a Serb”) — and although she had been raised in a wealthy family, she delighted in finding her work in a very different part of the nation.

“One drinks a dozen varieties of coffee and wine in their (folk songs) pursuit, at the oddest hours and places, and in the oddest company,” she once wrote to a friend.

Sidney Robertson copying California Folk Music Project recordings at her offices in Berkeley, California, in 1939. The recordings were sent to the Library. No photographer listed. Prints and Photographs Division.

Sidney Robertson copying California Folk Music Project recordings at her offices in Berkeley, California, in 1939. The recordings were sent to the Library. No photographer listed. Prints and Photographs Division.The recordings, made on acetate discs given to her by the Library for the project, have been preserved in what is now the American Folklife Center.

You can hear plenty of this online. Songs featured in the book are available on the Library’s website and via SoundCloud. The AFC features an online presentation of her career, including photographs, diagrams of various musical instruments and a StoryMap detailing her travels.

Her classical musical interests and progressive politics eventually led her to folk music and social work. Her federal career began in 1936 when she walked into the Library to ask “whether someone there could make clear to me what distinguished American folk song, from Spanish, Jewish or English, for instance.”

This led to work with the Resettlement Administration and, two years later, to her California work with another New Deal program, the WPA.

As a folklorist, she thought that America had its history written into the songs of working-class people and that immigrants formed a cornerstone of the national identity.

“America has her own boat songs and bandit songs, her Civil War songs and her love songs, stemming like the American race from many nationalities but after generations here stamped, in varying degrees, with the American mark.”

She also had pronounced ethical guidelines to treat her recording subjects as peers and partners. A stint early in her career working with influential folklorist John Lomax, whose recordings focused on Black people in the South, left her with mixed feelings. She regarded him as a “very warm, friendly, buffle-puffy of a man,” but was put off that when they worked with Blacks “he was acting as a plantation owner.”

At least she found Lomax to mostly be “very nice and extremely gentlemanly.” That was rarely the case with her male colleagues, as she was one of the rare women in the field in that era: “… this business of working with a lot of cross and worried men who dislike having a woman around or having to bother with her except In The Home (her capitalization) requires steady nerves, a thick skin and a sense of humor …”

She didn’t hesitate to put in the legwork herself. She lugged around a Presto recording machine, which used 12-inch acetate discs that recorded about five minutes per side. Recording sessions weren’t in studios, but in her subjects’ homes or local venues. She handled the recording machine, scribbled notes about the songs, took pictures and managed the singers and onlookers.

“She recorded popular tunes played by a band at a lively Mexican wedding, songs sung at a Hungarian New Year’s Eve party, and gold rush songs performed in noisy Tuolumne County bars,” Kerst writes. On another occasion, she noted that the recording was made on a dairy farm in “the milk house – occasional noises are due to milk running over cooling pipes.”

The WPA project, like the rest of the New Deal programs, was short-lived. The California work was done in under two years. After her marriage to Cowell in 1941, she made a few more folk music recordings – ranging from Appalachia to Nova Scotia to islands off the coast of Ireland – and published four albums from those works. She also collaborated with her husband on a book about Charles Ives, another influential composer.

Still, being married to such a famous man, particularly during the conservative turn of the country during the 1950s, meant that her star dimmed.

“She sort of became, and was very proud of being, ‘Mrs. Henry Cowell,’ ” Kerst says. “The ’50s were a time when forthright women were not supported for their forthrightness. I wish she had been able to get loose from that.”

The book is available in the Library of Congress Shop and via booksellers everywhere.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 3, 2024

My Job: Mineeya Miles

Mineeya Miles is a special assistant to the Health Services Division’s Wellness Program.

Tell us about your background.

I grew up in Prince George’s County, Maryland. In May 2023, I graduated from Delaware State University with a Bachelor of Science degree in kinesiology. My education fueled my passion for health and fitness, leading me to obtain my personal training certification shortly after graduation.

During my time at Delaware State, I was actively involved in health and wellness initiatives, gaining invaluable hands-on experience that complemented my classroom learning.

I then worked at Sibley Memorial Hospital in Washington, D.C., as a medical office assistant, where I gained valuable experience in patient coordination, record management and support of medical staff. The position enhanced my administrative skills and provided me with a comprehensive understanding of health care operations.

What brought you to the library, and what do you do?

I joined the Health Services Division in August 2023 as the division’s Wellness Program specialist. I serve as the primary point of contact for the Wellness Center and lactation rooms in the Madison and Adams buildings.

My responsibilities include inspecting facilities and reporting and coordinating maintenance requirements and repairs to ensure the facilities are in optimal condition. I also plan and execute on-site and online programs focused on promoting wellness and health among the Library staff.

Through these initiatives, I aim to enhance the overall well-being of the Library’s community, supporting the health needs of employees and foster a healthier workplace environment.

What are some of your standout projects?

In the short time I have been at the Library, I’ve contributed to several projects. I developed a tracking method to monitor use of the Wellness Center and improve the experience of users. I also oversee the blood pressure screening systems in the Madison Building, at the Taylor Street annex and at the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center, providing monthly reports to the chief medical officer.

I recently planned and coordinated a heart health webinar, delivering cardiovascular health information through expert-led sessions. And as the lead coordinator for relocating equipment from the Wellness Center at the Taylor Street annex to the Adams Building to accommodate the move of the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled to the Adams, I created a floor plan and am working on getting braille labeling for all of the wellness equipment.

I’ve also organized monthly lunchtime events in the Madison cafe to highlight health topics and health awareness months, and I helped to plan and coordinate this year’s Wellness Fair, in which over 200 participants engaged in wellness activities and health screenings.

What do you enjoy doing outside of work?

I enjoy traveling with friends and family to explore new places and cultures. Working out is another passion. Whether it’s hitting the gym, going for a run or trying out a new fitness class, I find it rejuvenating.

I also have a great love for seafood, and I enjoy discovering new seafood restaurants and savoring a variety of dishes. From fresh sushi to perfectly grilled fish, seafood is always a delightful culinary adventure for me.

What is something your coworkers may not know about you?

Before I majored in kinesiology in college, I was a biology major with aspirations to become a dermatologist. While my career path ultimately took a different direction, my passion for skin health and wellness never waned. I have a keen interest in researching herbal and natural foods, fruits and vegetables that promote clear and youthful skin, as well as a healthy gut.

Over the years, I have combined this knowledge with my background in kinesiology to develop my own probiotic juice and skincare routine. I enjoy experimenting with different ingredients and formulations to create products that are both effective and natural. These creations have become a hit among my friends and family, who often come to me for advice on maintaining healthy lifestyle options.

This blend of interests allows me to integrate my love for science and wellness in a unique and personal way. Sharing these homemade remedies and tips brings me joy, and it’s a rewarding way to stay connected with my original passion for dermatology while pursuing my current career.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

July 1, 2024

Saving the Sounds of History

In the dimly lit studio, just after the backing band starts, Mary Ford’s smooth voice cuts in: “Put your sweet lips a little closer to the phone, Let’s pretend that we’re together, all alone.” The sound is so vibrant it’s easy to imagine yourself in the Quonset Hut Studio in Nashville, Tennessee, where Ford recorded “She’ll Have to Go” in 1962.

The sense of immediacy increases as record producer Jim Fogelsong interrupts: “Once again, please,” he says, ending Take 1. On Take 3: “Hold it a second. Joe, the bass is just a little bit too hard.” Take 8: “Mary … move in just a touch.”

In 2024, Ford’s voice emanates not from Nashville, however, but from a speaker in Culpeper, Virginia — one of six in a custom-designed multitracking studio at the Library of Congress’ National Audio-Visual Conservation Center (NAVCC).

Audio design engineers fabricated the studio to preserve the vast collection of guitar virtuoso and sound recording innovator Les Paul, a pioneer of multitracking.

In 1962, Paul and Ford were spouses, musical collaborators and major mid-20th-century hitmakers. Paul listened in the control room as Fogelsong guided Mary and the band through takes.

The new multitrack studio is NAVCC’s most technically complex audio studio to date. Its infrastructure enables engineers to capture and package multiple elements of a multitrack work for access in a library cataloging system — a new capability at the Library.

But the studio is not alone in number or sophistication.

“We have some of the best specifications you’re going to find,” Rob Friedrich, head of the Audio Preservation Lab, says of the 20 support rooms and audio preservation studios engineers operate on NAVCC’s sprawling campus in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

The Library’s custom-designed multitracking studio. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The Library’s custom-designed multitracking studio. Photo: Shawn Miller.He should know. He joined NAVCC in 2011 having won three Grammy Awards, including a Latin Grammy, as an audio engineer for the Telarc label. He now supervises a staff of specialists who transfer audio from fragile or obsolete formats to preservation-quality digital files.

Along with studios, Friedrich and his staff have developed an array of cutting-edge sound preservation labs at NAVCC, where they work hand-in-hand with curators, archivists and librarians to acquire, preserve and share America’s sound heritage.

Preserving the Library’s audio collection is no small feat: At nearly 4 million and growing, it is the nation’s largest. It spans experimental recordings etched into wax cylinders in the 1890s to the most recent achievements in digital sound recording.

A trip to NAVCC’s subterranean storage vaults — once used by the Federal Reserve to safeguard billions in cash — brings home the almost mind-boggling range of formats and genres.

“We have commercial albums and singles in every format — 78s, 45s, cassettes, reels, CDs. We have hundreds of thousands of radio broadcasts. Recordings of sound effects. Environmental recordings, you name it,” recorded sound curator Matt Barton says.

On ceiling-high shelves in one vault, CD box sets of the Beatles sit next to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. There’s a music-box recording of “Amazing Grace.” Commercial LPs feature Billy Taylor, the Beach Boys and, for drag-car racing fans, “The Big Sounds of Drag.”

In another vault, master recordings of Andrés Segovia, Lawrence Welk and Bing Crosby are etched into 16-inch lacquer discs. Even after all of this time, they give off a scent, despite the chill. The vaults are kept at low temperature and humidity to slow down degradation of materials.

In other vaults, the NBC collection contains upward of 40,000 hours of radio broadcasts from 1935 to 1971. Master recordings in the Universal Music Group collection showcase Ella Fitzgerald, Bill Monroe and Jascha Heifetz, to name a few.

Often, before a collection proceeds to a studio for digitization, items have to be stabilized. In one lab, specialists wash lacquer discs, the most vulnerable of formats.

“They constantly undergo a chemical degradation process called exudation,” explains audio engineer Melissa Widzinski. It leaves a white haze that, over time, can cause irreparable damage.

To clean a disc, she places it on a turntable. Its arm has a small brush and cleaning fluid, applied as the disc revolves. A water rinse follows. Then, a tiny vacuum threads through each groove picking up moisture.

Next, the disc goes into a cabinet with shelves of perforated racks and a fan. The door closes, and the lacquer dries completely within minutes.

In another lab, preservationists use specialty ovens to bake tapes that have absorbed too much moisture from the air, causing their layers to separate. Once heated overnight, “it’s essentially like dehydrating them, pulling the moisture out,” Widzinski says.

In one unusual instance earlier this year, a tape had too little moisture, not too much.

A French radio performance of composer Gunther Schuller’s music arrived in the Audio Preservation Lab looking like — not audiotape. A hockey puck? A blob? No one could say for sure.

To rehydrate the solidified brown mass, audio engineer Bryan Hoffa placed just enough water in a round plastic bucket — the kind home-improvement stores sell — to cover the bottom. He wedged an empty reel inside the bucket above the water, topped the reel with a flange, then set the tape on the flange and closed the lid.

Within 24 hours, the water vapor had rehydrated the tape. When Hoffa plays the digitized file now, the sound resonates.

“This is the creative process,” Friedrich says of Hoffa’s seemingly simple yet carefully considered approach — he spent months doing research before treating the tape.

In other labs, optical-assisted technology extracts sound from wax cylinder recordings. In one space, a system dubbed IRENE uses a tiny ultra-high-resolution camera to image grooved discs that are too fragile or damaged to play with a stylus. Afterward, software translates the images to sound.

“There were some hundred Les Paul discs that we could not have transferred without IRENE,” Friedrich says.

Given the size of the Library’s sound recording collections, sound preservationists have to balance time-intensive methods with expanded research access.

To qualify, the tapes must be in good condition. “They don’t have to be baked or spliced or have any other kinds of repairs done to them,” Chroninger says.

In two studios, he operates up to eight decks simultaneously at two- to four-times normal cassette playback speed and can transfer the A and the B sides of tapes at the same time.

In another studio, 16 vintage reel-to-reel tape machines transfer 32 hours of recorded sound in a single hour. Friedrich jokes the room is his “magnum opus” for production speed.

As in Chroninger’s studios, tapes have to be good quality. Engineers just finished digitizing the enormous NBC collection. Years earlier, it was transferred from disc to tape at the Library, making it a known quantity.

The studio’s decades-old reel-to-reel machines operate as if they were new thanks to NAVCC’s “amazingly knowledgeable” maintenance specialists, Friedrich says.

Maintenance engineers have expertly restored all kinds of legacy playback equipment, including a 16-track player that captured some of Paul’s hits.

Now, his artistry lives on in high fidelity at the Library. And in the studio built to preserve it, other unique multitracks — music of Liza Minnelli, Max Roach, the Gershwins — can be preserved for future generations.

“It’s because of the Les Paul collection,” Friedrich says. “We’re in a position to do it now. We’ve never been able to do that before.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 27, 2024

Freud’s Notebook: “To Remember is to Relive”

—This is a guest post by Meg McAleer, a former historian in the Manuscript Division.

Sigmund Freud returned again and again to the problem of memory as he formulated his theories of psychoanalysis during the 1890s, as the Library’s significant collection of his papers show.

“What is essentially new about my theory,” Freud wrote in this letter to fellow physician and confidante Wilhelm Fliess, “is the thesis that memory is present not once but several times over, that it is laid down in various kinds of indications.” The second page of this letter sketches the progression of memory from perception (“W”) to the unconscious (“Ub (II)”) and eventually to consciousness (“Bew”).

Freud refined his theories over time in significant ways but remained committed to the notion that the past exerts a powerful influence over the present as memories embedded in the unconscious break through into consciousness through selective, altered and fluid remembering and forgetting.

Slipped into a pocket and kept close to the body, pocket notebooks are intimate, hidden and always accessible.

Freud purchased this small leather-bound notebook while vacationing in Florence in the waning summer of 1907. Its cover bears the Italian words “Ricordare è rivivere” (“to remember is to relive”). Freud owned many similar notebooks, filling them sequentially through the decades with jottings of names, addresses, expenses, ideas and observations.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 26, 2024

Treasures Gallery: The First Italian Cookbook

—This is a guest post by Lucia Wolf, a reference specialist in the Latin American, Caribbean and European Division.

In the late 1400s, Maestro Martino, a chef from Como, in Lombardy, created the first Italian cookbook, “Libro de arte coquinaria,” or “The Art of Cooking.” The full, translated title reveals more of Martino’s background and qualifications: “Book of the art of cooking composed by the extraordinary Maestro Martino, former cook of the Most Reverend Monsignor Chamberlain and Patriarch of Aquileia.”

Martino’s recipes presented clearly written instructions on how to manipulate basic ingredients and transform them into actual dishes. Previously, recipes were transmitted orally or simply jotted down as lists of ingredients without explanations on how to use them.

Centuries later, another cook in Lombardy began recording recipes in a modest booklet, likely in service of a noblewoman. The unidentified 19th-century cook included recipes she wished to document for “Domenica,” who may have been her assistant.

Following the initial pages, the book delivers familiar local recipes handwritten and typed by various individuals and passed on from one generation of cooks to another, dating from around 1910 to 1930. The book’s only hint to its authorship is an inscription on the blue marbled cover: “Zia Annita,” or Aunt Annita.

This plain recipe book carries the secrets of a native Italian cuisine that may eventually have vanished from memory had they not been recorded and transmitted by generations of local cooks.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 18, 2024

2024 National Book Festival Lineup

The 2024 Library of Congress National Book Festival returns to the Washington Convention Center on Saturday, Aug. 24. The festival’s theme this year, “Books Build Us Up,” explores how reading can help connect us and inform our lives. It’s through books that readers can develop strong bonds with writers and their ideas – relationships that open the entire world, real or imagined, to us all.

Throughout the day, attendees will hear conversations from authors of various genres across the festival’s many stages. Award-winning author James Patterson will chat about his newest novel “The Secret Lives of Booksellers and Librarians: Their Stories Are Better Than the Bestsellers,” and James McBride will discuss his new work “The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store.”

Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin will take readers on an emotional journey in her latest book, “An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960s,” a story dedicated to the last years of her husband’s life after serving as an aide and speechwriter to Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy. Erik Larson, author of “The Demon of Unrest: A Saga of Hubris, Heartbreak and Heroism at the Dawn of the Civil War,” will bring to life the pivotal five months between the election of Abraham Lincoln and the start of the Civil War.

Sandra Cisneros celebrates the 40th Anniversary of “The House on Mango Street,” Abby Jimenez, author of “Just for the Summer,” and Casey McQuiston, author of “The Pairing,” join forces to chat about their romance novels. Rebecca Yarros talks about her bestselling “Empyrean” fantasy series including “Iron Flame,” sequel to her bestselling “Fourth Wing.”

On some timely topics, Annalee Newitz, author of “Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind,” and Peter Pomerantsev, author of “How to Win an Information War: The Propagandist Who Outwitted Hitler,” discuss the impact, now and historically, of political propaganda and misinformation. Also, Joy Buolamwini, author of “Unmasking AI: My Mission to Protect What Is Human in a World of Machines,” and Kyle Chayka, author of “Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture,” dive deep into the impact of technology.

Explore how cooking can inspire with Tamron Hall and Lish Steiling’s “A Confident Cook: Recipes for Joyous, No-Pressure Fun in the Kitchen.”

Grammy Award-winning vocalist Renée Fleming explores the healing power of music in her latest book, “Music and Mind: Harnessing the Arts for Health and Wellness,” on stage with renowned psychologist and neuroscientist Daniel J. Levitin, author of “I Heard There Was a Secret Chord: Music as Medicine.”

Young adult readers will enjoy a conversation with Candace Fleming, author of “The Enigma Girls: How Ten Teenagers Broke Ciphers, Kept Secrets and Helped Win World War II,” and Monica Hesse, author of “The Brightwood Code.”

For children, featured authors will include actor and author Max Greenfield debuting his new children’s book, “Good Night Thoughts.” National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature Meg Medina will share her latest children’s book, “No More Señora Mimí,” a salute to the caregivers who enter a child’s tender world.

The National Book Festival will take place on Saturday, Aug. 24 from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in Washington, D.C. Doors will open at 8:30 a.m. The festival is free and open to everyone.

Interested attendees not able to join the festival in person can tune into conversations throughout the day. Events on the Main Stage will be livestreamed on loc.gov/bookfest. Videos of all presentations will be made available at loc.gov and on the Library’s YouTube channel shortly after the festival.

Visit loc.gov/bookfest to learn more about attending the festival. A comprehensive schedule will be available on the website and announced on the Library’s Bookmarked blog in the coming weeks. Subscribe to the blog for updates on festival plans and more. The National Book Festival celebrates creators and invites the public to be curious about the Library and its collections in their own creative or scholarly pursuits.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 17, 2024

Look Up! It’s Blashfield’s Mural

The artwork of the magnificent Jefferson Building reaches its pinnacle, literally, with a painted homage to learning and progress set high up in the dome.

Each day, visitors and researchers who enter the Main Reading Room crane their necks as far back as they can to take in “Human Understanding,” a mural created by American artist Edwin Howland Blashfield at the apex of the soaring, coffered dome.

In Blashfield’s work, a beautiful female figure, set against a soft blue background, lifts away a veil of ignorance. On her right, a cherub holds a book of wisdom. To her left, another cherub seems to beckon viewers far below to join in a quest for knowledge.

In the collar just below, 12 painted figures represent countries or epochs that, when the mural was completed in 1896, were thought to have contributed the most to Western civilization.

Rome, for example, represents administration, Islam physics, Greece philosophy and Italy the fine arts. The English figure, representing literature, holds a copy of Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” The character symbolizing Judea and religion sits beside a pillar inscribed with the biblical admonition to love thy neighbor as thyself.

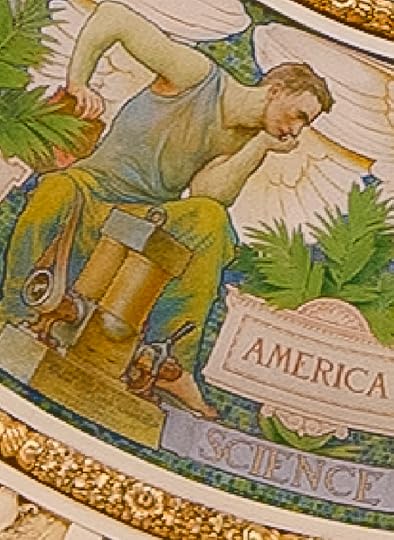

One character might look familiar: The figure embodying America (and science) was modeled on a young Abraham Lincoln, here sitting in a machine shop, pondering a problem of mechanics.

A character modeled on Abraham Lincoln represents America and science. Photo: Shawn Miller

A character modeled on Abraham Lincoln represents America and science. Photo: Shawn Miller“Human Understanding” is full of coded meaning, leaving its significance not always apparent to the upturned faces some 125 feet below. But there is, of course, another aspect to the scene that’s impossible to miss: the awe-inspiring beauty of Blashfield’s work and its glorious setting.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 12, 2024

Treasures Gallery: Surviving Hiroshima

This is a guest post by Meg McAleer, a former historian in the Manuscript Division. It also appears in a slightly shorter version in the May-June issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, which is devoted to the June opening the David M. Rubenstein Treasures Gallery.

Haruo Shimizu, a Japanese schoolteacher, survived the United States’ bombing of Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945. One year later, he wrote down his memories of that horrific day on 24 pages of lined rice paper in his careful penmanship.

Shimizu remembered boarding a trolley that morning to visit a friend before reporting to work at a munitions factory. At approximately 8:15 a.m., his world exploded with “a silver-white flash, like that of magnesium powder used in taking a photograph, high up in the sky.” The U.S. bomber Enola Gay had dropped an atomic bomb, nicknamed “Little Boy.”

Torrential rain began to fall. Shimizu grew disoriented: “A tremendous clap of thunder went on and huge columns of brown clouds with dust and flame were making sheer screens all around.” The dead and dying surrounded him. “Some of them were carrying their wounded wives on their shoulders and some their dead children in their arms. They were all desperately shouting for help and calling aloud the names of their families.” The next day, he saw a B-29 plane circling the city. His anger erupted: “What the hell do you think there is still left to be bombed in this devastated city?”

Aerial photo of Hiroshima taken several months after the atomic bomb was dropped on the city. Photo: U.S. Army. Prints and Photographs Division.

Aerial photo of Hiroshima taken several months after the atomic bomb was dropped on the city. Photo: U.S. Army. Prints and Photographs Division.Shimizu returned to his native Hokkaido. Though afflicted by radiation poisoning and trauma, he secured a job as an interpreter in an Otaru hotel that served as an American military club during the U.S. occupation. There he met and befriended Willard C. Floyd, a 19-year-old soldier from Bliss, Idaho.

The account of Hiroshima, written by Shimizu in flawless English in 1946, was for Floyd, so that he would understand the terror, devastation and loss hidden beneath the soaring mushroom cloud. Floyd eventually moved to Arizona after returning from the war and ran a barber shop. He died in 1985. His family gave his papers, including Shimizu’s manuscript, to the Library in 2020.

Writing about and sharing traumatic memories can lead to self-healing for some people. Shimizu was a Walt Whitman scholar who taught at Japanese colleges and published on Whitman’s poetry. Like the poet, Shimizu captured the inhumanity of war in his writing, yet he retained his faith in humanity.

Shimizu retired from teaching Gifu Women’s University in 1986. He died in 1997. You can read more of his war account, and of his brief but sincere friendship with Floyd, in this blog post.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers