Library of Congress's Blog, page 10

October 25, 2024

NASA and the Library Send Poetry into Space

In the moments before NASA’s Europa Clipper was set to launch Oct. 14 from the legendary Kennedy Space Center, everything got quiet.

All eyes were fixed on a towering SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket that would carry NASA’s largest spacecraft ever designed for a planetary mission on a 1.8-billion-mile journey.

The mission to explore Jupiter’s moon, Europa, was in the making for decades and imagined for far longer. Galileo first discovered Europa through a homemade telescope in 1610. Now, scientists believe Europa is another water world covered with an icy crust and may hold the ingredients for life.

The launch had been delayed four days due to Hurricane Milton whose eye passed directly over the Kennedy Space Center near Cape Canaveral, Florida — a reminder that we, too, are on a planet. Many wondered: Would something go wrong at the last moment? Were all systems still go for launch?

As the countdown clock kept ticking, a crowd of scientists, mission planners, family, friends — and the poet laureate of the United States — gathered outside under clear blue skies to watch.

Then, they started counting down together. 10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1. Liftoff.

Fire and billowing smoke were visible first. A few seconds passed before the rocket’s roar could be heard. As it lifted higher in the sky and turned out over the ocean, vibrations from the boosters rushed back toward land, rumbling through one’s entire body, drawing tears and then cheers.

Poet Laureate Ada Limón, who wrote an original poem for the mission, wiped a tear from her eye and kept watching as she saw it disappear into the sky.

“I kept thinking, is all of this ok?” she said. “I don’t know. Then everyone started clapping.”

Ada Limón at Cape Canaveral for the launch of the Europa Clipper. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Ada Limón at Cape Canaveral for the launch of the Europa Clipper. Photo: Shawn Miller.It was the beginning of a nearly six-year journey to reach Jupiter and Europa in 2030.

Exactly two years ago, on Oct. 14, 2022, an invitation arrived from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory for Limón to write a poem to serve as a message from Earth and to help convey the mission’s quest for knowledge. Limón agreed almost immediately and then got to the hard work of composing a poem within three short months.

On early drafts, Limón said she felt as if she was failing. She was trying to write about Europa and to educate people about the mission details she’d received from NASA. But it wasn’t working.

“You need to stop writing a NASA poem and start writing a poem you would actually write,” Limón’s husband, Lucas Marquardt, told her.

So, Limón started drafting a poem about Earth, our most beloved planet and one of her best inspirations for poetry. “That’s when my poem took off.”

She wrote of the mysteries of Earth, “the whale song, the songbird singing” — and how it is “the offering of water” that unites us.

“O second moon, we, too, are made of water, of vast and beckoning seas,” Limón wrote.

By early 2023, Limón was submitting the poem in her own handwriting to be engraved on the spacecraft’s metal vault plate.

“In Praise of Mystery: A Poem for Europa,” was revealed publicly in June 2023 during a special reading at the Library.

NASA collaborated with Limón and the Library on a Webby Award-winning public engagement and media campaign that invited people worldwide to sign on to the poem and send their names to space with it on a microchip. More than 2.6 million people from around the world signed on.

“I write from a very intimate, personal I, and I had to take the I out. This poem is a we poem. This is all about the we. And ‘we’ wasn’t just human beings but all creatures, and it’s the first poem, I think, I’ve dissolved myself out of. It no longer belongs to me. It belongs to all of us,” Limón said of the poem, which was just published by Norton Young Readers as a picture book in October with illustrations by Peter Sís.

On the eve before the poem was launched into space, Limón told mission scientists, engineers and family members who gathered for a “star party” that even though the poem is set to travel billions of miles on Europa Clipper, “every word is written in praise of this planet” — because every NASA scientist knows Earth is “the best planet,” she said.

“It has been the honor of my life to work on this project,” Limón told the mission team. “I propose that if this is the beginning of the journey for the Clipper that it might also be the beginning of a journey for us. And might we think about where we will be in the next five to six years? Who we will be? Who we have helped? … The small kindnesses, the large kindnesses. Any of those things. The possibilities of humankind.”

Robert Pappalardo, the mission’s lead scientist, and Jordan Evans, the project manager, presented Limón and the Library with an exact replica of the vault plate from the spacecraft, engraved with Limón’s poem for Europa and the names of 2.6 million people who signed on.

Limón watches the Europa Clipper head into space. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Limón watches the Europa Clipper head into space. Photo: Shawn Miller.Like the replica of the Voyager space mission’s golden record that carried “The Sounds of Earth” into interstellar space in 1977 (now on view in the Library’s Treasures Gallery), the Europa Clipper vault plate will have a home forever in the national library in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division to match the one exploring our solar system. The vault plate replica is set to be formally transferred to the Library in December.

Pappalardo said the mission will expand our horizon from one ocean world to another.

“Soon our craft, crafted by human hands, emblazoned with poetry, will lift through the sky,” he said, “and pierce the Kárman line, through the Van Allen Belts, beyond the Hill sphere, into the ether, the quintessence, heaven.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

October 22, 2024

Halloween Heartthrob: The “Chicken Heart” that Gobbled Up the Globe

The panic? You could feel it coming through the illuminated dial of your radio. Darkness had fallen. Static and interference. Sirens. Screams. The implacable monster. The scientist who knows humanity is the walking dead.

“All mankind, doomed!” he cries.

And this merciless beast of death is … is … a chicken heart.

Yes, friends, it really happened. “Chicken Heart,” a seven-minute episode of the “Lights Out” radio series that aired just before midnight in March 1937 was a cheesily effective landmark of the Golden Age of Radio. Living on for decades through rebroadcasts, remakes, in syndication and on records, it snaked its way into the childhood memories of everyone from horror master Stephen King to comedian Bill Cosby, becoming a campy horror cult favorite.

It was the brainchild of the singular Arch Oboler, a 5-foot, 1-inch titan of radio drama from the 1930s to the 1950s. He was rich, he was famous, he worked with everybody who was anybody — Bette Davis, James Stewart, Claude Rains, Joan Blondell — and influenced everything from radio classics such as “Inner Sanctum” to television’s “The Twilight Zone.” He was shocking people with “Chicken Heart” a year before Orson Welles’ famous “War of the Worlds” radio broadcast in 1938.

“…no discussion of the phenomenon of radio terror, no matter how brief, would be complete without some mention of the genre’s prime auteur — not Orson Welles, but Arch Oboler, the first playwright to have his own national radio series, the chilling Lights Out,” King wrote in “Danse Macabre,” his 1981 book on the horror genre.

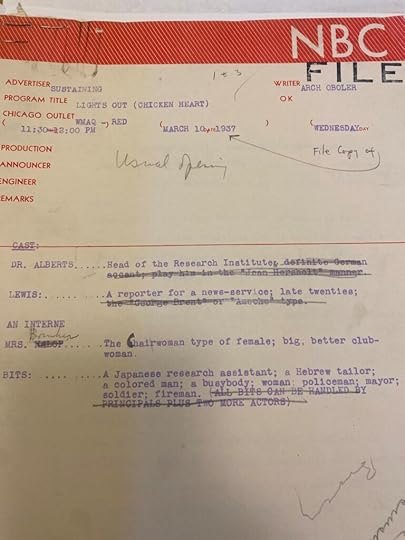

NBC Radio title page for “Chicken Heart” script in its first broadcast. National Audio-Visual Conservation Center.

NBC Radio title page for “Chicken Heart” script in its first broadcast. National Audio-Visual Conservation Center. The Library preserves Oboler’s papers, recordings, screenplays, short stories and so on. It’s a big collection — 364 boxes, 107 tape reels, 127 cassettes, a total of some 127,000 items — for Oboler lived a big, busy life. Frank Lloyd Wright designed his house (though it was never fully built). After radio began to diminish in pop culture, he wrote and directed one of the first 3D films, “Bwana Devil,” a hit in 1952 and was working until his death in 1987.

Going through folder after folder, box after box — the correspondence and notebooks and contracts and newspaper clippings all seem infused with the man’s restless energy, a writer so wound up he lay in bed at night, smoking cigarettes while dictating dialogue so a secretary could type it up into gold the next day.

In the collection, you’ll find what appears to be the original “Chicken Heart” script, with plenty of penciled edit marks. An NBC-branded title sheet lists the airdate as Wednesday, March 10, 1937, from 11:30 to midnight on Chicago’s WMAQ. (You can come into the Library to hear various recordings of the show, but it’s easier to stream on any number of websites; it’s not hard to find.)

It was the most unforgettable “Lights Out” episode, King wrote, both in spite and because of its ridiculous premise.

“Part of Oboler’s real genius,” King wrote, “was that when ‘Chicken Heart’ ended, you felt like laughing and throwing up at the same time.”

We’ll get to the plot — and that classic ending — in just a second.

Suffice it to say for now that, as the decades passed, new generations of kids heard it rebroadcast and word of mouth spread all over again. Cosby, at the height of his comedy career in the mid-1960s included a stand-up bit about it scaring him so bad as a kid that he set the family’s couch on fire. He included it on “Wonderfulness,” a 1966 comedy album, and told it again on his animated television show “Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids” in the 1970s.

A Chicago native born into a working class, highly cultured Jewish family in 1909, Oboler loved music and stories with big ideas, things that took on the issues of the day. He broke into radio in the late 1920s, writing for variety and drama broadcasts in his hometown.

“Lights Out” and its creepy little heart was created by Wyllis Cooper, an NBC writer in Chicago, in 1934. The 15-minute show, airing at midnight, was replete with the supernatural, gory deaths and wild sound effects. It was a hit, soon expanding to half an hour, and Wyllis moved on to Hollywood.

Oboler took over in and made the show his own. He put the era’s fascination with science and sweeping international politics into bizarre settings. He used stream-of-consciousness narration, ironic settings and radio’s gift for horror — listeners could never see the monster, the thing, the terror.

His first show was about a paralyzed girl who was buried alive. Listeners were outraged, appalled and fascinated. He ran “Lights Out” for two years (and would return off and on over the next decade), but moved on to more substantial fare.

“Bathysphere,” a 1939 radio play, was later inducted into the Library’s National Recording Registry. By then, he had his own show, “Arch Oboler’s Plays.” His story collection, “Fourteen Radio Plays,” was, according to the dust jacket, “the first collection of radio plays by a single dramatist to ever to appear in book form.”

In 1941, Radio magazine called him “the richest writer in the world” (he was getting $3,000 for half-hour episodes of a new series). The magazine good naturedly said he was “a wack job” who had a face like a “gnome” and was “the worst dressed writer in the world.”

It’s unlikely that any of that was literally true — but, hyperbole aside, in the years before another beast called television took over the world, the magazine accurately said he showed “radio’s place as an important drama medium, one with great possibilities.”

Oboler was brilliant, King observed, at radio’s dialogue-as-description, throwing out an idea that triggered the mind’s “innate obedience, its willingness to try to see whatever someone suggests it see, no matter how absurd. … Radio is, of course, the ‘blind’ medium, and only Oboler used it so well or so completely.”

The dreaded chicken heart starts growing, from the original script. National Audio-Visual Conservation Center.

The dreaded chicken heart starts growing, from the original script. National Audio-Visual Conservation Center. OK, ready? Here’s what happened in “Chicken Heart.” (You’ve been warned!)

Dr. Leon Alberts, a scientist, had kept a tiny chicken heart beating in a test tube for 17 months as part of an experiment. The tube was accidentally knocked over and broken, the chicken heart got mixed in with some chemicals. When the staff comes back to the lab, they find that the little heart has grown into a thick, fleshy thing the size of a chair … and it is both (a) still growing, doubling in size by the hour, and (b) still beating.

Neither process can be stopped. Water, fire, ammo, bombs — nothing. It spreads over the lab, town, state, nation, continent, planet, blub-blub, blub-blub, a fleshy, pulsing blob, still beating, still growing, smothering everything on Earth.

In manic desperation, Alberts finally rushes to a prop plane with a pilot, trying to outrun it. Alberts monologues about mankind’s hubris — and suddenly the plane’s engines splutter!

“The motor! It’s cut out!” the pilot shouts wildly. “We’re in a spin! I can’t get out of it!”

“I told you,” the doctor says grimly. “Doomed!”

“No! NO!” the pilot shouts. “NNNOOO!! We’re falling right into it! Into the heart!”

He screams. The whine grows louder, the wind rushing, the plane in free fall. The chicken heart beats louder. Blub-blub, BLUB-BLUB.

And then a sickening wet splat. The end. A gong sounds. Seven minutes and change, the whole episode, a bit of American pop culture history that just wouldn’t die.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

October 17, 2024

Genealogy Research: Fact and Fiction

This is a guest post by Candice Buchanan, a reference librarian in the History and Genealogy Section.

Not long after I turned 14, one of my English teachers handed out Emily Brontë’s “Wuthering Heights.” The 1847 British novel, taking its title from the name of a remote, imposing farmhouse, concerned itself with the fates of two families among the landed gentry in Yorkshire. It’s long been a classic of world literature, but teenage me knew nothing about the characters or the plot. I flipped it open and there, on one of the opening pages, were diagrams of the Linton and Earnshaw family trees. I still remember the sensation: My heart leapt.

I had already been struck by the magic of genealogy after a fateful walk through the neighborhood cemetery in my little Pennsylvania hometown, captivated by the intrigue and allure of local and family history. And now, right in front of me, was a diagram of three generations of ancestors and neighbors living out a drama that included complex relationships, old houses, a rural village with a church and cemetery and even a ghost.

So I imagined myself as a modern genealogist tracking down this 18th– and early 19th–century history. Had Heathcliff, his companions at Wuthering Heights and the other characters in dear old Thrushcross Grange really lived, how could I track down their history? They would have all been gone for more than a century. Would their weathered tombstones still be legible? Did their houses still stand? Did the heirs of Hareton and Cathy keep the family papers? The portraits? And the servants; how could I track down their less documented but equally compelling lives? Every type of archival record that might have been created formed a to-do list in my imagination.

When I graduated high school years later, I still hadn’t gotten over it. “Wuthering Heights” was the topic of my senior essay and it left a lasting impression on my work today.

How so, you ask?

Sheree Budge, my former colleague in the History and Genealogy Section (she recently retired), spent a delightful age building a Research Guide for fellow lovers of both fiction and genealogy. I had the privilege to work on the project with her, often in lively and animated conversations, as we debated how the books we read for fun fit with the goals we value in our work.

In the guide, we propose topics, themes and subject headings to encourage both veteran and novice researchers to take a break and enjoy a fictional turn through family histories. Drama, mysteries, ghost stories, science fiction, young adult — we tried to cover the waterfront. The list is by no means the limit to the creativity on the subject; it is just a jumping off point to capture your imagination and curiosity. (There’s also a guide to help you get started on genealogy searches.)

I am partial to the mysteries and ghost stories, many of which were not written with the intention of being classified as genealogy fiction, despite the plots that often involve the investigative techniques used in serious family history sleuthing. In local folklore, ghost stories often have grains of truth. Embellished and exaggerated over generations, they may take many forms, and may lose or gain critical details in the retelling. Genealogists and local historians often detect and flesh out the facts to be found in these stories by documenting a thorough family tree or chronicling the history of a house or property. In many genealogy fiction novels, the protagonists do just the same, even if they don’t always mean to do so. Characters, like real-life researchers, are driven by a need to know that leads them to conduct research and interviews and ultimately seek the best sources to tell the real story.

As “Wuthering Heights” illustrated for me, almost any book may be viewed though genealogy-colored glasses. Family history is human history — it contains every plot and storyline. When the characters in a novel go off the rails, change their identity or ride off into the sunset, I can’t help thinking that those missing ancestors in my family tree may have done exactly the same thing! And because fact can truly be stranger than fiction, discussing novels with fellow researchers often leads to comparisons with in-real-life discoveries. Ask any genealogist to share the story of their most amazing breakthrough and you will probably hear a plot that could rival your favorite bestseller!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

October 15, 2024

Unbuilt America: A Nation of the Imagination

-This is a guest post by Sahar Kazmi, a writer-editor in the Office of the Chief Information Officer. It also appears in the September-October issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Imagine this: It’s a crisp fall afternoon in the nation’s capital. You stand beside the colonnades at the base of the Washington Monument and look up at an elaborate statue of the first president among his rearing horses. Next, you take in the vaulted ceilings and intricate arches of the Gothic palace of the Library of Congress. In the evening, you grab a bite along the Washington Channel Bridge, a modern rendering of Florence’s Ponte Vecchio.

Perhaps in another life. This vision lives only in the imagination, a story of architectural designs that went unrealized. A Washington, a world, that might look quite different were it not for economic pressures, political will or pure chance. For as many grand and iconic structures as we now know by heart, there are tenfold more that were never built at all.

The Library as proposed by architect Alexander Etsy. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Library as proposed by architect Alexander Etsy. Prints and Photographs Division. The Library’s Prints and Photographs Division hold a fascinating array of architectural drawings going back as far as the 1600s. They offer a look into what could have been had the stars aligned.

The well-known obelisk of architect Robert Mills’ Washington Monument was originally envisioned on a raised colonnade, punctuated by great statues. John L. Smithmeyer and Paul J. Pelz’s Italian Renaissance vision of the Library of Congress beat out a dramatic Gothic castle from Alexander Esty in a pair of congressionally authorized design competitions.

Much later, in the 1960s, architect C.W. Smith imagined D.C. in the Florentine style, drawing a contemporary version of the Italian city’s famed Ponte Vecchio bridge. Her idea, designed as an open-air pedestrian hangout complete with cafe tables and striped awnings, was never commissioned by the city.

Paul Rudolph, whose modernist, geometric designs can be found across America today, had a few misses too. A sprawling attempt at combining residential features with traffic flow in a growing New York City, Rudolph’s Lower Manhattan Expressway, or LOMEX, drew political debate for years before it was eventually scrapped.

His concept for the 1964 New York World’s Fair also was ambitious. Dubbed the spacey-sounding “Galaxon,” Rudolph’s architectural drawing is about 19 feet long, featuring a dramatic concrete walkway leading to an enormous, tilted flying saucer-shaped viewing structure. It was rejected in favor of Gilmore D. Clarke’s more earthly “Unisphere” steel globe.

Space age urban utopianism was a common theme in midcentury design aesthetics. Architect and industrial designer Wilbur Henry Adams, who became better known for his work on the Oliver tractor, once was an inventive student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. While there, he mocked up the “Study Playroof,” an ultramodern urban playground in the middle of Manhattan. Here, children ride on seesaws and bicycles beside the wing of an expansive helicopter landing deck. Just another day in New York City!

One of Frank Lloyd Wright’s final proposals, The Key Project, was never built. Taliesin Associated Architects. Prints and Photographs Division.

One of Frank Lloyd Wright’s final proposals, The Key Project, was never built. Taliesin Associated Architects. Prints and Photographs Division.Perhaps the most perfect example of this style is a creation from none other than Frank Lloyd Wright. In the last project he worked on before his death, Wright collaborated with architect William Wesley Peters on a futuristic wonderland for Ellis Island. Called the “Key Project,” their colorful rendering seems a far cry from Wright’s quintessential prairie style. In it, a series of huge domes surround a circular housing podium intersected by triangular sundecks and winding towers. It’s Trek-y, a little Seussian, and positively sci-fi.

Architecture is often a catalog of the unmade. Lucky, then, that even our imagined futures are saved alongside our histories at the Library.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

October 9, 2024

“LatinoLand” and Hispanic Heritage Month

From the vibrant rhythms of cumbia, salsa and mariachi at quinceañera parties to the countless taco trucks across the country, Latinos — both immigrants and U.S.-born — have been grappling for generations with the challenge of preserving their identity while navigating American culture.

Despite their long-standing presence, political clout and rising purchasing power, Latinos remain mostly outside the mainstream, writes author and journalist Marie Arana in her new book, “LatinoLand: A Portrait of America’s Largest and Least Understood Minority.”

Featured at this year’s National Book Festival, “LatinoLand” offers a deep dive into Latino history in what is now the United States since the 16th century. As the Library joins in celebrating Hispanic Heritage Month, Arana’s work serves as a powerful reminder: Latino history is American history.

“We have been here since before the United States was formed and we helped it to form; whole areas were built by Latino hands,” Arana said in an interview. “I want the myth that we are newcomers to go away because we have a long and proud history. Latinos helped build this country and will continue to shape its future. … These facts need to be taught in schools.”

Arana is a Peruvian American author of fiction and nonfiction with a long career in literature and journalism. She has worked as editor-in-chief of The Washington Post’s Book World, studied as a distinguished visiting scholar at the Library’s John W. Kluge Center and later served as the Library’s literary director. In 2020, the American Academy of Arts and Letters recognized her lifetime’s work with their Arts and Letters Award. Her other books include “Bolivar: American Liberator” and “Silver, Sword and Stone: Three Crucibles in the Latin American Story.” Her 2001 memoir, “American Chica: Two Worlds, One Childhood,” was a finalist for the National Book Award.

In this book, Arana takes stock of the current situation of some 65 million Hispanics (which includes Latinos), who make up nearly 20% of the national population. They account for 15% of all eligible voters and wield a purchasing power of $3.4 trillion — “a whole country unto itself,” as Arana notes in an interview. By 2050, there will be some 100 million Americans of Hispanic heritage, nearly 30% of the population, according to census projections. It’s no wonder that historians, cultural institutions, political candidates and advertisers are increasingly focusing on the nation’s second-largest demographic.

To make it clear: Latinos fit into the U.S. Census’ Hispanic category. According to the agency, the term “Hispanic” is an ethnicity and it refers to people who trace their ancestry to Spain, Mexico, Central America, South America and the Spanish-speaking nations of the Caribbean. While people often use Hispanic and Latino interchangeably, the terms are not the same: The first one refers to those of Spanish-speaking nations while the latter includes those from English- and Portuguese-speaking countries and cultures. The recent terms “Latinx” and “Latine” were born of a movement pushing for gender-neutral language and inclusion.

This question of Latino identity has long sparked books, films, TED Talks and heated social media debates about who truly “belongs” here.

In seeking to debunk persistent myths about Latinos and highlight “lives not often seen,” Arana enriches her narrative with stories from 237 interviews with Latinos from diverse backgrounds. These include housekeepers, grape pickers, artists, ambassadors and C-suite executives. She also examines subgroups, like Afro Latinos and “Lasians” (Latinos and Asians). This results, Arana writes, in a “mind-reeling multitude” that is difficult to categorize.

In attempting to explain the core Latino mindset, Arana argues that much like earlier immigrants, full assimilation into the mainstream “is no easy enterprise.” They want to fit in, have their children thrive as full-fledged Americans, work and be counted as citizens. But they also want to retain their customs, language, “motherland senses of identity” and “be valued and respected for it.”

“Here in LatinoLand, in this wildly diverse population, in our yearning for unity, in our sheer perseverance, lives a vibrant force. A veritable engine of the American future,” she writes.

Nicholas Brown-Cáceres, assistant chief of the Library’s Music Division, reflects on the experience of millions of Latinos straddling two worlds, bound by language and history. As a Honduran American, he takes pride in having learned Spanish from his mother and growing up in a bicultural home. He feels equally at home eating baleadas (flour tortillas filled with mashed refried beans, cream and crumbled hard cheese) and burgers, having spent summers and Christmas in Honduras celebrating with his cousins and abuela.

He agrees with Arana’s premise that the bond uniting Latinos “is buried deep” in their history and alive in their culture: “Just go to a fiesta. It is there.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

October 7, 2024

The Season of Edgar Allan Poe: Autumn, Halloween and The Falling Darkness

Edgar Allan Poe died 175 years ago today, Oct. 7, 1849, in a Baltimore hospital under circumstances that no one has ever fully understood.

He was en route from speaking engagements in Virginia to New York when he went missing in Baltimore. After several days, he was found the night of Oct. 3, the day of a local election, lying outside a pub that doubled as a voting precinct. He could barely speak, apparently had been beaten and was wearing shabby clothes that were not his. There have been endless theories about he came to be found in this state, from rabies to a brain tumor to severe alcoholism. Many historians say it’s most likely that he was the victim of cooping, a brutal form of voting fraud in which victims were violently forced to impersonate legitimate voters at the polls, oftentimes with liberal amounts of alcohol involved.

In any event, Poe lingered for four days in a windowless hospital room, never regaining coherence. He died at 5 a.m. on Oct. 7. He was 40.

Among his literary masterpieces was “The Raven,” which began with one of the most famous lines in American poetry: “Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary…”

Though Poe and the poem are now closely linked with his sometimes home and burial place of Baltimore (the titular bird is now the mascot for the city’s NFL franchise), he was born in Boston and educated as a youth in England and the poem was written in New York. It first appeared in the New York Evening Mirror on Jan. 29, 1845. It was buried on an inside page amid ads for lamps and sheet music.

Poe spent a lot of time thinking about burying things (like tell-tale hearts), but this particular newspaper copy was headed for immortality.

“The Raven,” the dark tale of a grieving young lover encountering a black bird with a fiery stare and a one-word vocabulary, is one of the most anthologized and instantly recognizable poems in American history.

The conclusion of “The Raven” as first published in the New York Evening Mirror on Jan. 29, 1845, shoehorned in among advertisements. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

The conclusion of “The Raven” as first published in the New York Evening Mirror on Jan. 29, 1845, shoehorned in among advertisements. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.The Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division preserves an original copy of the Evening Mirror that day, marking the moment the poem entered the national culture.

It was clearly inspired by Poe’s tragic circumstances.

Poe and his first cousin, Virginia Eliza Clemm Poe, had married in 1836, when she was 13 and he was 27. There has been much speculation about their relationship (even for the era, she was extremely young to be married) but the pair seemed devoted. Her adoring letters refer to him as Eddie.

The couple was struggling to get by on the earnings from Poe’s literary career when, in 1842, Virginia contracted tuberculosis. She was just 18. It was a slow and terrible way to die — as the bacterial infection spread in the lungs, it caused bloody coughs, chills, fever, weight loss and night sweats. As the years ground on, the disease waxed and waned. Poe, already possessed of a macabre imagination and often debilitated by alcohol, later described the period this way: “I became insane, with long intervals of horrible sanity.”

It was during this terrible period that he wrote “The Raven.” He seemed to be anticipating, with great dread, the depression that would crush him after Virginia’s death:

“Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December;

And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.

Eagerly I wished the morrow;—vainly I had sought to borrow

From my books surcease of sorrow—sorrow for the lost Lenore—

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore—

Nameless here for evermore.”

He published it in January 1845, with the bird’s resounding refrain of “Nevermore” becoming a sensation. The editors at the Evening Mirror considered its remarkable gothic nature, haunting phrases, perfect meter and recognized genius: “It will stick to the memory of everybody who reads it,” the paper wrote.

In an essay published the next year, “The Philosophy of Composition,” Poe uses the poem as an example of his work method. He never mentions Virginia’s impending death as an influence, but late in the essay he does explain the poem’s dark power.

The first part of the poem is straightforward, he wrote. The beautiful Lenore has died. Her grieving suitor is reading late one night, trying to fend off his grief. A raven raps at the window and flies in when it is opened. The narrator, more bemused than alarmed, reasons that the bird has escaped its owner, happened by his illuminated window late at night and sought refuge. It can mimic speech, like a parrot, but knows only one word: “nevermore.”

A little weird, sure, but this is all rational.

But then the narrator reclines on a sofa where Lenore had often lain, resting his head “on the cushion’s velvet lining.” Meant to be a comfort, the soft fabric instead reminds him that Lenore’s cheek had often lain on this exact spot. The shock sends his mind into hallucinations:

“Then, methought, the air grew denser, perfumed from an unseen censer

Swung by Seraphim whose footfalls tinkled on the tufted floor.”

The world has warped — seraphim are celestial creatures, winged angels — and our narrator now believes that he is hearing the footsteps of invisible spirits on the carpet all around him.

Now things turn brutal. The narrator knows perfectly well that the bird can only say “Nevermore,” but he begins to ask it hopeful questions — Is there spiritual help for his pain? Will he and Lenore be reunited in the afterlife?

“Nevermore,” thunders the bird, lashing him with the pain he wanted. This is a sort of perverse masochism, Poe writes in the essay, as the narrator is impelled by “the human thirst for self torture.” The more pain, the more he likes it: “…he experiences a frenzied pleasure in so modeling his questions as to receive from the expected ‘Nevermore’ the most delicious because the most intolerable of sorrow.”

Then, just when we think it’s all over, Poe drives in the dagger.

In the last stanza, he changes the tense from past to present, from a night in the past (“.. it was a night in bleak December”) to the horrifying present. The narrator hasn’t been remembering a quaint evening of yore, but is reporting from right now and … the raven is still there. We have no idea of how much time has passed, but we get the idea it is considerable because the narrator says “still” twice. There are no more whiffs of invisible angels, only the glare of a demon’s eye:

“And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming,”

The bird, we know now, will never leave. There is no balm in Gilead. There is no escape from grief. The last use of the word “Nevermore,” Poe wrote, “should involve the utmost conceivable amount of sorrow and despair.”

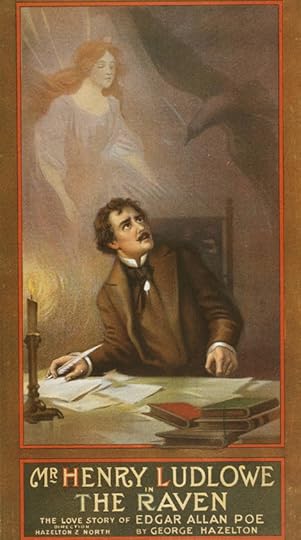

Poster promoting a 1908 play of “The Raven” by George Hazelton. Print: U.S. Lithograph Co. Prints and Photographs Division.

Poster promoting a 1908 play of “The Raven” by George Hazelton. Print: U.S. Lithograph Co. Prints and Photographs Division.Virigina died two years and one day after “The Raven” was published. While her corpse lay on the deathbed, Poe had an artist paint her portrait. It is the only image of her known to still exist.

In life, as in “The Raven,” Poe never seemed to fully escape his grief. He was sometimes found after dark in the years to come, sitting beside her grave. His last completed poem was “Annabel Lee,” in which the unnamed narrator is haunted, much like the protagonist of “The Raven,” by the death of his beautiful young love. At the poem’s conclusion, the narrator pictures climbing into the tomb with her corpse:

“And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side

Of my darling—my darling—my life and my bride,

In her sepulchre there by the sea,

In her tomb by the sounding sea.”

Autumn is Poe’s season, the time of year when his dark, dazzling works seem to most come to life. Halloween still seems like a holiday he would have created if hadn’t already existed; the long night, the ghosts, the fears of The Thing in the Dark. And finally, there is the everlasting sense of horror from the last lines of “The Raven” — there will never be any solace from the grave; only the dark, deep, terrible silence.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

October 3, 2024

Finding Latinos in Film

In his epic “El Norte,” award-winning filmmaker Gregory Nava charted the tragic journey of siblings Enrique and Rosa from Guatemala to Los Angeles in pursuit of the American dream. The film’s themes still resonate in this Hispanic Heritage Month four decades later.

“El Norte,” released in 1983, was inducted into the Library’s National Film Registry in 1995. It offers a heart-wrenching portrayal of the immigrant experience; today, it is considered an important landmark in Latino cinema and American independent film.

Born in San Diego, Nava has intimate knowledge of the border and its people — growing up, he had family on both sides. As a filmmaker, he wants to ensure that Latinos are seen, beyond stereotypes, for their vast cultural complexity.

Latinos make up about 20% of the U.S. population but only 2% of actors in movies. But, Nava says, advancing true Latino inclusion in film is not just a math challenge.

Numbers are important, he said in an interview, but it’s more important that Latinos are creating Latino stories and acting in lead roles: “We’re writing our stories, directing our stories, telling who we are for this country and for our industry.”

Nava’s work is included in a Library research guide prepared last year by junior fellows Mateo Arango, Karla Camacho and Madeline Griffin and project mentor María Daniela Thurber of the Latin American, Caribbean and European Division in collaboration with experts from the Library’s Moving Image Research Center and its National Audio-Visual Conservation Center.

The guide features thematic and chronological filmographies from 1893 through 2023, documentaries, books, posters and external websites curated to increase understanding of Latino film. It also features interviews with filmmakers like Alexis C. Garcia, Aitch Alberto, Alejandra Vasquez, Patricia Cardoso and Alex Rivera.

In addition to “El Norte,” Nava’s “Selena” and Luis Valdez’s “Zoot Suit,” also featured in the guide, have been inducted into the Film Registry, which includes 22 films with significant Latino representation on and off camera.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

October 1, 2024

The Great Pyramid of Pei

Paris is a tribute to centuries of French architects. The Gothic towers of Notre Dame, limestone domes of Sacré-Cœur, iron latticework of the Eiffel Tower and golden dome of Les Invalides visually define one of the world’s great cityscapes.

To those, add the glass-and-metal pyramid of a Chinese American who brought an ancient Egyptian form — and a controversy — to the historic city’s heart.

In 1983, architect I.M. Pei was commissioned to devise a solution to a growing problem: the outdated entrance to the massive, magnificent Louvre museum no longer could accommodate increasing throngs of visitors.

Pei proposed an audacious remedy: Dig out the central courtyard and build a massive subterranean hall that would give visitors easy access to the museum’s three wings and also create space for shops, restaurants and other facilities.

Above the hall would loom the new entrance: a 71-foot-high glass pyramid through which visitors and light would flood into the below-ground spaces.

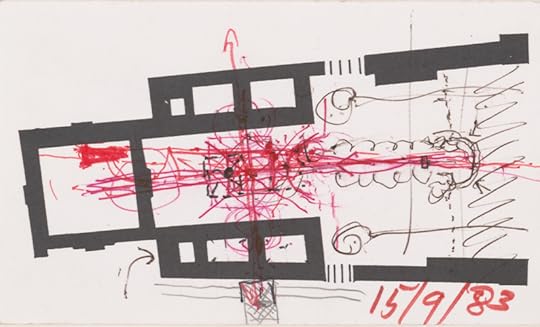

Pei’s sketch shows the axes of the Louvre courtyard. From this, he determined the center of his pyramid by connecting the site to the Arc de Triomphe, 2 miles away through the open end of the courtyard. Prints and Photographs Division.

Pei’s sketch shows the axes of the Louvre courtyard. From this, he determined the center of his pyramid by connecting the site to the Arc de Triomphe, 2 miles away through the open end of the courtyard. Prints and Photographs Division.The intrusion of modern materials and ancient Egyptian form among the historical structures — the Louvre is a former royal palace — set off a controversy dubbed the “Battle of the Pyramid.” Was the great pyramid of Pei an anachronistic blot on a revered cityscape or an inspired, ingenious solution blending artfully into its setting?

The Library’s Prints and Photographs Division holds original models and site plan sketches by Pei that give a sense of his thinking and process. In addition, the Manuscript Division holds Pei’s papers — some 180,000 items of correspondence, proposals, scrapbooks and more.

“You are never sure about these things until they are built,” Pei said at the opening of the new Louvre entrance in 1989.

One never is: A committee of prominent artists once objected to plans for the Eiffel Tower, calling it “useless and monstrous,” a “hateful column of bolted sheet metal.” As with the Eiffel, controversy over Pei’s pyramid faded into the past, leaving another monument to human imagination in a city renowned for them.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 26, 2024

Ada Limón & Poetry in the National Parks!

—This is a guest post by Rob Casper, head of poetry and literature in the Literary Initiatives Office.

Ada Limón spent her summer as many Americans do — visiting some of the country’s spectacular national parks. The U.S. poet laureate, however, visited with a special purpose: to kick off her signature project, “You Are Here: Poetry in the Parks,” connecting poetry to nature.

“I want to champion the ways reading and writing poetry can situate us in the natural world,” Limón said of the project. “Poetry’s alchemical mix of attention, silence and rhythm gives us a reciprocal way of experiencing nature — of communing with the natural world through breath and presence.”

Limón’s initiative consists of promoting poetry through visits to national parks as well as an anthology of new nature poems.

This summer, Limón visited five National Park Service units across the country — Cape Cod National Seashore, Mount Rainier, Redwood, Cuyahoga Valley and Great Smoky Mountains national parks. At each, she revealed poetry installations in cooperation with the Poetry Society of America and the National Park Service. The initiative concludes with visits to Everglades National Park in October and Saguaro National Park in December.

At the entrance to the Beech Forest trail at Cape Cod, visitors encountered a picnic table covered in black cloth, facing picturesque Beech Forest Pond. Limón read “Can You Imagine?” by Mary Oliver. It begins:

For example, what the trees do

not only in lightning storms

or the watery dark of a summer’s night

or under the white nets of winter

but now, and now, and now – whenever

we’re not looking

After reading the concluding lines, Limón then stepped to the table. Pulling back the cloth, she revealed “Can You Imagine?” printed on a powder-coated aluminum panel.

Afterward, a park ranger led a guided tour of the trail, read other poems by Oliver along the way and spoke about her life. One of the country’s most popular and celebrated poets, Oliver spent over 50 years in the area and often walked the trail herself. Her papers are now in the Library’s Manuscript Division.

Returning to the table after the tour, Limón pulled out her notebook and tried her hand at the initiative’s prompt: What would you write in response to the landscape around you? She’s encouraging readers to share their responses using the hashtag #YouAreHerePoetry.

A park ranger looks out at Mt. Rainier while seated at a picnic table emblazoned with one of the “You Are Here” poems. Photo: Shawn Miller.

A park ranger looks out at Mt. Rainier while seated at a picnic table emblazoned with one of the “You Are Here” poems. Photo: Shawn Miller.The aptly named Paradise location at Mount Rainier National Park, at 5,500 feet, offered a spectacular setting of snow-covered mountains for Limón to discuss the poem she chose for the park, “Uppermost” by A. R. Ammons. Later, at the reveal of a picnic table emblazoned with the poem, she called up a special guest to join her: her brother, Bryce Limón, who worked as a ranger at Rainier from 2011 to 2014.

Two days later, Limón arrived at Redwoods National and State Parks. While there, the traveling party stopped to see some of the park’s famed big trees along the Newton B. Drury Scenic Parkway. Later, at the Crescent Beach day use area, morning fog gave way to sun and breezes, perfect for an extended reading.

Limón finished the reading with commissioned poems she wrote for NASA and the National Climate Assessment, followed by the poem “Redwoods” by Dorianne Laux in the “You Are Here” anthology. She also read the featured poem for the park: “Never Alone” by Francisco X. Alarcón.

The next day, she traveled to her childhood home near Sonoma, California — a home she recently purchased.

In her backyard, in the beautiful California sunshine, Limón pointed out the lemon tree she planted as a child — a perfect example of how the project connects to her own life in the most personal of ways, as the natural world does to us all.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 24, 2024

Richard Morris Hunt: Architect of the Gilded Age

— This is a guest post by Susan Reyburn, a writer-editor in the Publishing Office. It also appears in the September-October issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Who was Richard Morris Hunt, and why was he so famous? Why was he forgotten, even as images of his creations continued to illuminate hefty coffee table books and characters on HBO’s “The Gilded Age” referred to him by name?

For impossibly wealthy industrialists, Hunt was the architect of choice in building, furnishing and decorating mansions that combined Old World aesthetics with American ingenuity and spirit. For millions of poor European immigrants, his work was among the first things they saw on approaching New York Harbor, with the Statue of Liberty standing atop the monumental pedestal he designed.

The grand salon in The Marble House, Newport. Photo: Michael Froio.

The grand salon in The Marble House, Newport. Photo: Michael Froio.Some of those new arrivals, as domestic servants, would become very familiar with Hunt’s floorplans as they hurried up and down hidden back stairs. Others might eventually have lived in one of his apartment buildings or his retirement home for “respectable aged and indigent females.”

“When viewed as a cultural leader, Hunt emerges as astonishingly relevant to the critical assessment of America’s ‘master narrative,’ ” writes historian Sam Watters in his new book, “The Gilded Life of Richard Morris Hunt: Architecture & Art for an American Civilization,” just published by Giles Ltd. in association with the Library. “Tourists may not know his name, but they experience the buildings and art that he and his colleagues and patrons conceived and collected to build an American civilization. Their museums, libraries, and mansions extended what President Lincoln, on the verge of the Civil War, called ‘our national fabric, with all its benefits, its memories, and its hopes.’ ”

A native of Brattleboro, Vermont, and the son of a U.S. congressman, Hunt was born in 1827. He descended from Revolutionary War patriots and ascended to the highest ranks of his profession. His widowed mother, Jane M. Leavitt Hunt, ferried her five children to Europe in 1843, calling the endeavor “venturesome in the extreme,” and an opportunity for advanced schooling that was not yet available in the United States, especially in the arts.

Hunt’s 1852 drawing of a Venetian palazzo. Prints and Photographs Division.

Hunt’s 1852 drawing of a Venetian palazzo. Prints and Photographs Division. The young Hunt became the first American to study architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, becoming a construction inspector at the Louvre and taking extensive sketching trips through Europe and the Middle East.

With Yankee bona fides and European training, he returned to the United States in 1855, then in his late twenties, determined to spread the Beaux-Arts gospel and give America architecture that matched its ambitions. But Hunt also was practical, tending to the wishes of his often-demanding clientele and telling his son, “If they want you to build a house upside down standing on a chimney, it’s up to you to do it.”

None other than Ralph Waldo Emerson cited Hunt and his brothers William, a leading painter, and legal scholar Leavitt as representing a remarkable American family. The sage of Concord might have been further impressed had he met the other siblings — Jonathan, a physician dedicated to working with the poor, and Jane, also an accomplished artist.

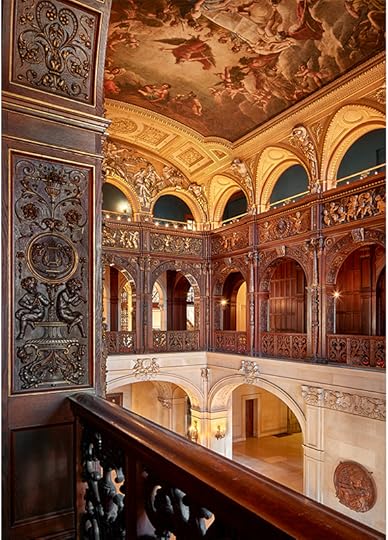

The main hall of Ochre Court in Newport, with its “Feast of the Gods” mural. It’s now the main adminstration building at Salve Regina University. Photo: Michael Froio.

The main hall of Ochre Court in Newport, with its “Feast of the Gods” mural. It’s now the main adminstration building at Salve Regina University. Photo: Michael Froio.He regarded Richard as a “thinking soul … horsed on a robust & vivacious temperament” who “expressed with the vigor & fury … fine theories of the possibilities of art.” Emerson soon added Richard to his short list of men who were making major contributions to the young nation’s progress, among them naturalist John Muir and transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau.

The best-known surviving works on Hunt’s lengthy resume include the Fifth Avenue main entrance to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Breakers and Marble House mansions in Newport, Rhode Island, and Biltmore, in Asheville, North Carolina. In addition to his residential castles for Vanderbilts and Astors, his range was extraordinary, from early apartment buildings and skyscrapers to modern hospitals, university facilities and churches.

But Hunt built more than buildings: He was essential in developing the nascent American architectural field as a profession, with established standards, business practices and training curricula. As a plaintiff in an 1861 lawsuit, Hunt successfully argued that clients pay professional architects fees for their creative and conceptional work, elevating the role of the architect above that of traditional builders and construction supervisors.

His technical innovations included the use of lightweight terracotta hollow block floor construction and enclosed iron vertical supports to improve fireproofing. Hunt’s office also mastered the art of magnificent presentation drawings, encouraging clients to see what was possible in the hands of a cultured architect.

As well-travelled, well-educated, self-appointed arbiters of good taste, Hunt and his circle took it upon themselves to instruct the public in what was beautiful and important.

He co-founded the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Institute of Architects — he later served as its president — and the Municipal Art Society. Unusual among architects, Hunt encouraged his clients to acquire and later bequeath art collections to institutions for safekeeping and exhibition, making them accessible to the public.

Another of Hunt’s designs: A women’s dormitory at Hampton University, now known as Virginia-Cleveland Hall. Photo: Michael Froio.

Another of Hunt’s designs: A women’s dormitory at Hampton University, now known as Virginia-Cleveland Hall. Photo: Michael Froio.His contemporaries regarded him as the dean of American architecture; even with some critical failures and lost commissions, his was a stellar 40-year career, bolstered by his gift for self-promotion and mentoring successful young successors. Not long after he was memorialized in granite and bronze off Fifth Avenue in Central Park, Hunt’s work was overtaken by modernism. He disappeared from the national conversation on art and culture that he had so fervently helped to create.

It was Hunt’s robust interdisciplinary range that first intrigued Watters.

Ford Peatross, the founding director of the Center for Architecture, Design, and Engineering at the Library, tipped him off to the richness of the Richard Morris Hunt Collection when it was acquired in 2010.

Peatross suggested Watters might write about and catalog the material as he had done with the collection of pioneering photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston. Watters was further drawn to “Hunt’s astounding range of art-related activities — architect, collector, educator — in diverse social settings, all to the end of building a ‘civilized’ America,” and he plunged into the deep end of Huntiana. Fortunately, Mari Nakahara, Peatross’ eventual successor, was already there.

Nakahara knew the Hunt holdings well, having worked with the material when it was housed at the Octagon, the museum of the American Architectural Foundation, in Washington, D.C., before the collection came to the Library.

Hunt’s 1893 design of the administration building at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Prints and Photographs Division.

Hunt’s 1893 design of the administration building at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Prints and Photographs Division. Watters and Nakahara worked their way through Hunt’s well-preserved archive of more than 10,000 items, including an unpublished biography by his wife, Catharine Howland Hunt; numerous sketchbooks; architectural drawings from his student days to his decades as head of his own firm; notable photography from the United States and abroad; scrapbooks that he and Catharine assembled filled with reference images; and his library of architecture books, with some French and Italian tomes dating to the 17th century.

“People may not know that the Library collects architectural materials,” says Nakahara, who is especially partial to Hunt’s 1847 iron bridge drawing from his days at the École. “The Prints and Photographs Division holds over 4 million items in about 140 collections related to architecture, design and engineering. The easiest way to study and enjoy our collection is via our research guide. In this digital era, though, people believe everything is available online, but that is not true. I strongly recommend that people see the originals.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers