Library of Congress's Blog, page 6

April 3, 2025

George Washington and King George III — Exhibit Showcases Common Ties

George Washington and King George III were on opposite sides in the Revolutionary War, with Washington leading the Continental Army to victory over King George’s Britain. Thus, America’s independence in 1783.

What’s seldom taught in classrooms, however — and what has not been previously well understood — is how much the two leaders had in common.

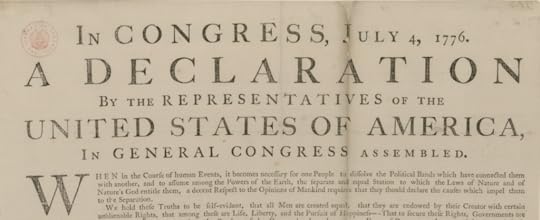

A major new Library exhibition, “The Two Georges: Parallel Lives in an Age of Revolution,” uses original documents such as letters, diaries, maps, newspapers, cartoons, to shed light on striking likenesses between the two. All of these are on display online, in an exhibit in the Jefferson Building and in a companion book. You’ll see stunning items such as Washington’s copy of the Declaration of Independence, his notes on a draft of the U.S. Constitution as it was being composed by the Constitutional Convention and an abdication speech King George drafted (but never delivered) following Britain’s defeat by American forces.

Visitors explore the new exhibition, “Two Georges: Parallel Lives in an Age of Revolution,” at the Library. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Visitors explore the new exhibition, “Two Georges: Parallel Lives in an Age of Revolution,” at the Library. Photo: Shawn Miller.The approach allows viewers, both online and in person, to “hear the Georges speaking in their own voices and get to know them on their own terms,” said Julie Miller, the Manuscript Division’s historian of early America, who curated the exhibit.

The show originated about ten years ago, when the Library partnered with the Royal Archives and several other institutions on the Georgian Papers Programme, a project to digitize George III’s papers. Washington’s papers had been digitized by the Library’s American Memory project in the 1990s. Conversations between historians of the era began to flow.

“It became clear from the start that the Georges were similar in certain surprising ways that I don’t think anyone had ever thought about,” said Miller.

The show brings together Washington’s papers from the Library and George III’s papers from the Royal Collection and the Royal Archives in England. Objects and images from London’s Science Museum, the Maine Historical Society, the Museums at Washington and Lee University, Washington’s Mount Vernon and other repositories are also included.

A close-up of George Washington’s copy of the Declaration of Independence. Manuscript Division.

A close-up of George Washington’s copy of the Declaration of Independence. Manuscript Division.The exhibit traces the two men’s stories from birth to death, mixing original documents and artifacts with large-scale graphics and decorative elements. It’s also a study in, of all things, documents written in 18th-century cursive.

“Small handwriting is difficult to read,” said John Powell, the exhibit’s director. “It’s helpful to have blow-ups, and we wanted to make the exhibit visually pop as well.”

A three-minute introductory film explores popular conceptions of the Georges — the myth about Washington and the cherry tree, for example, and beliefs about King George’s madness. From there, visitors encounter a more complex story, including that Washington, born in 1732, spent the first half of his life as a model British gentleman and a committed subject of the British Empire. When he was 27, an invoice shows him ordering volumes of goods for his Mount Vernon plantation like a man to the manor born: handkerchiefs, green tea, a large Cheshire cheese and a hogshead (or cask) of “best Porter,” all from London merchant Robert Cary. This was hardly the lifestyle of a dangerous revolutionary.

As a planter, Washington immersed himself in agriculture, as did George III. Both had a deep fascination for new methods of farming, gardening and landscape design developed in 18th-century Britain. The two read many of the same books, including a lavishly illustrated 1754 volume of natural history that is included in the exhibit.

Even after Washington became president, Miller said, “he’s writing home to his farm manager and talking about the trees he wants planted a certain way.”

A 1786 political cartoon satirized King George III and his interest in farming, showing him in the barnyard with Queen Charlotte. Windsor Castle is in the far background. Drawing: S. W. Fores. Prints and Photograps Division.

A 1786 political cartoon satirized King George III and his interest in farming, showing him in the barnyard with Queen Charlotte. Windsor Castle is in the far background. Drawing: S. W. Fores. Prints and Photograps Division.Across the Atlantic, George III was much the same. A 1786 cartoon shows a casually dressed King George with his spouse, Queen Charlotte, feeding chickens and pigs in a farmyard. “George III liked to dress up in ordinary clothes and go out and see how the pigs were doing,” Miller said.

Both Georges were devoted family men and homebodies, with shared values such as constancy, accountability, restraint and frugality. This led them to act as paternal, benevolent leaders, Miller says, but only up to a point. Neither man had time for abolitionists, and Washington used slave labor to help make him wealthy.

“Neither recognized the idea that people did not in fact own the right to own other people,” Miller said.

A 1761 ad in the Maryland Gazette shows Washington seeking to recover four enslaved men who escaped from Mount Vernon. A 1799 document lists people enslaved on his plantation.

Other historical items include Washington’s commission as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, a codebook that American spies used during the Revolution to outwit the British (Washington’s numerical code name was 711) and a plan for a failed scheme to kidnap George III’s 16-year-old son, Prince William, while he served in the Royal Navy in New York City during the war.

Opening night fun at “The Two Georges” exhibit. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Opening night fun at “The Two Georges” exhibit. Photo: Shawn Miller.Also included are a 1782 letter from King George to his prime minister accusing the Americans of “knavery” and a 1789 teacup and saucer inscribed with “Huzza, The King is well.” It celebrates the king’s recovery from a major episode of the still-undefined illness that earned him the moniker “The Mad King.”

At the exhibit’s end, a striking 1820 painting by Samuel William Reynolds shows King George close to death. Unlike images of the younger George, bewigged and fashionably dressed, Reynolds depicts an elderly man with long gray hair and beard gazing into the distance.

“The Two Georges” kicks off the Library’s America 250 celebration, marking the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. The exhibit will be on view in the Jefferson Building southwest exhibition gallery for the next 12 months; after that, the Science Museum will mount a companion exhibit in London.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 31, 2025

Ned Rorem’s Brilliant and Beautiful Scrapbooks and Diaries

Ned Rorem could never stop thinking. Or writing, composing or socializing.

He kept datebooks, scrapbooks and diaries, the last of which went for thousands of pages over decades. He composed more than 500 art songs, three symphonies, four piano concertos, more than half a dozen operas and on and on. These fill volumes and folders and boxes in the Library’s Music Division, a dizzying testament to one of the great musical lives of the American 20th century.

A bon vivant in Paris and New York for more than half a century, Rorem seemed to know all the high-brow artistic set — Pablo Picasso, Balthus, James Baldwin, Jean Cocteau, Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, Tennessee Williams, Noël Coward. He went on benders with Kenneth Anger, the notorious underground filmmaker. Openly gay when that was a shocking rarity, his published diaries were wildly indiscreet, creating a sensation when they were published six decades ago.

“The mediocrity of this ship’s passengers,” he tartly noted on one trans-Atlantic voyage in 1955, “is beyond belief.”

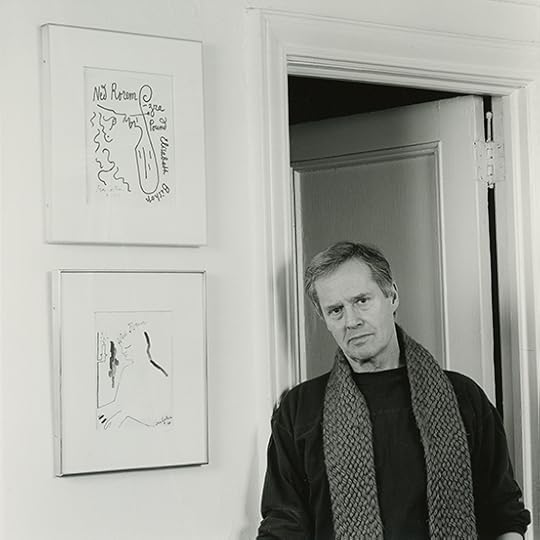

Ned Rorem in 1992, posing with artwork sketched for him by the artist Jean Cocteau. Photo: Nancy Lee Katz. Prints and Photographs Division.

Ned Rorem in 1992, posing with artwork sketched for him by the artist Jean Cocteau. Photo: Nancy Lee Katz. Prints and Photographs Division.He won a Pulitzer Prize, Fulbright and Guggenheim fellowships, music commissions from famous foundations and ASCAP’s Lifetime Achievement Award and served as the president of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Time magazine once declared him “the world’s best composer of art songs.” In 2004, the French government awarded him the Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters for his “significant contribution to the French cultural inheritance.” His works are still widely performed and recorded.

He was born in Indiana in 1923, got his master’s degree at The Juilliard School in New York and was soon off to Paris, the talented boy wonder. He lived there for nearly a decade.

Here he is in that city, writing in his diary on Halloween of 1956, with ominous strains of the Cold War beating down on Europe: “Winter is terribly here. And another war seems well on its way, war like a searchlight wail of mammoths straining the sky. All around in Africa and Hungary is this positive and bleeding unrest. I’m scared.”

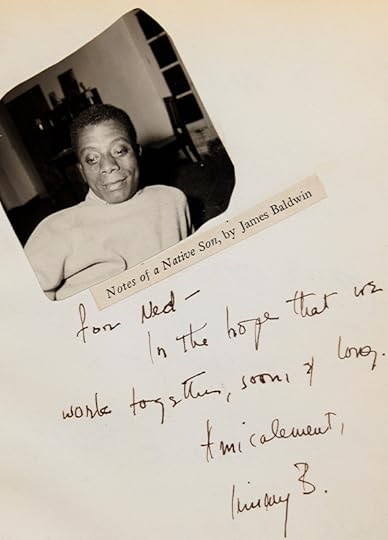

Here’s a page from one of his scrapbooks, in which he was forever getting guests to write, scrawl and sketch. It’s a casual snapshot of Baldwin, the famed novelist and activist, who scribbled on July 8, 1958: “for Ned, In the hope that we work together, soon, & long.” He signed it, “Jimmy B.”

Novelist and essayist James Baldwin, one of Rorem’s many famous friends, inscribed a page in one of Rorem’s scrapbooks. Music Division.

Novelist and essayist James Baldwin, one of Rorem’s many famous friends, inscribed a page in one of Rorem’s scrapbooks. Music Division.Rorem, who died at age 99 in 2022, had been slowly donating his papers to the Library over the years. They are dazzling, in-depth and insightful. The scrapbooks are both portfolio-sized and in small notebooks, all of them filled with drawings, signatures, witty one-liners from famous friends.

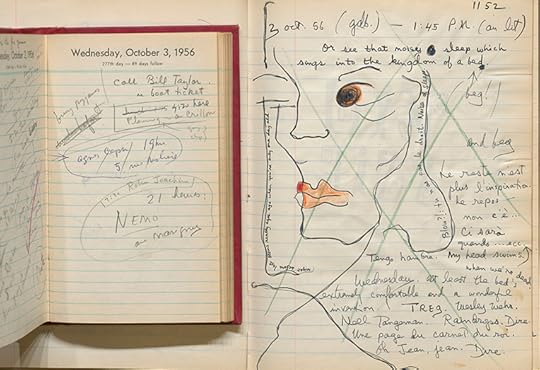

Most of his entries are just a paragraph or two; a few go for several pages. They were so neatly and compulsively kept that you can open a datebook to a specific day, where you’ll see jottings of phone numbers and addresses and appointments, then open the corresponding diary to see what he penned on that day, then compare that passage to the finished manuscript page. Over and over again, his longhand diary entries are almost the same as the published piece. His diary entries are dated, but he cut the specific dates from the finished book, leaving them with more of an impressionistic, and less of a journalistic, feel.

Rorem’s datebook for Oct. 3, 1956, and his diary entry for the same day. Music Division.

Rorem’s datebook for Oct. 3, 1956, and his diary entry for the same day. Music Division.The overall impression? Even now, one is brought up short by his mix of intimacy, intelligence and celebrity. You can imagine how this played out when his first two diaries were published in the 1960s.

“The Paris Diary of Ned Rorem,” adapted from his journals from 1951-55, wrote the New York Times in its obituary of the man, “mentioned hundreds of the famous and the obscure while serving up a pastiche of explicit reports on his sex life, pieces of music criticism and charming anecdotes.”

“Name-dropping is one thing,” the article said. “With the gossipy Mr. Rorem, it could reach the level of carpet-bombing.”

“Worldly, intelligent, and highly indiscreet,” The New Yorker opined.

He recounts spending an evening with an aging Alice B. Toklas in her famed apartment on rue Christine, more than a decade after the death of her life partner, Gertude Stein, both icons of the American expatriate community in Paris. He wrote this passage out in longhand but cut it from the published version: “And she is old, old, small and old as a unicorn or a raven flying through the sad old-fashioned smoke of other autumns, deaf, with Virgil’s style and accent, quick as a whip.”

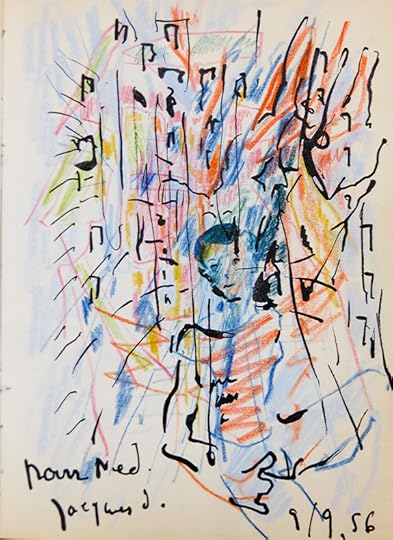

A colorful 1956 sketch in one of Rorem’s many scrapbooks. Music Division.

A colorful 1956 sketch in one of Rorem’s many scrapbooks. Music Division.Flipping through the pages, there are often random one-liners or phrases he seems to be trying out. “I’m in love again for the first time.” A bit of dialogue: “The phone: ‘But how will I recognize you?’ ‘I’m beautiful.’ ”

Just when you think it’s all chaff and gossip, there is a plainspoken passage from the artist alone with his work, struggling.

“What a disheartening mess it always is: the first days’ fumbling at a long work. A song or something in one sitting is almost done before begun. But the opera on Petronius that I’ve been plotting for months is now rather started so I don’t know where I am; it’s more than just music, theater. … Slowly, as days pass, if we are routine, a form appears and finally (as with wars in history) we recoil and see it all as a whole. There it is, finished; now will it work?”

Late in life, he paused to consider it all, this relentless minute cataloguing, this constant self-examination. In “Lies: A Diary, 1986-1999,” he wrote on Jan. 15, 1996: “Why keep a journal? To stop time. To make a point about the pointlessness of it all. To have company. To be remembered. For there is much to be recalled, with no one to do the recalling.”

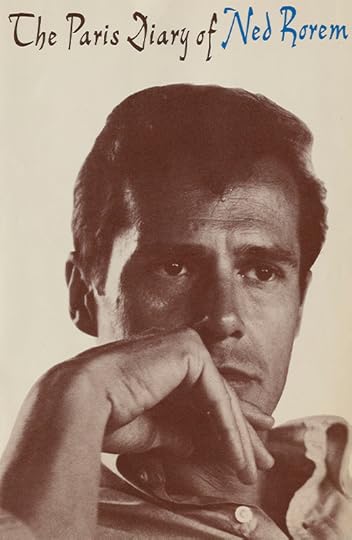

One of the many editions of Rorem’s Paris diaries, which created a sensation when published in the 1960s. Music Division.

One of the many editions of Rorem’s Paris diaries, which created a sensation when published in the 1960s. Music Division.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 27, 2025

Reimagining the Lives of Enslaved Children

—This is a guest post by Olivia Dorsey, an innovation specialist in the office of the Chief Information Officer. It also appears in the March-April issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Entering the living quarters of a late 18th-century plantation house, the last thing you might expect to see is a rainbow of colors, dancing in the breeze. Figures frozen in a moment of play trail tissue paper along worn, dusty floorboards. Through a veil of vibrant colors and textures, a portrait appears: A Black girl stares ahead, her hand gently perched on the back of a chair.

The piece, titled “Complex,” was one of many on view as part of artist Maya Freelon’s immersive exhibition “Whippersnappers: Recapturing, Reviewing, and Reimagining the Lives of Enslaved Children in the United States” at Historic Stagville in Durham, North Carolina.

The Bennehan-Cameron family enslaved more than 900 people at Stagville, once one of the largest plantations in the state, at at its peak in 1864.

Today, the state-run site maintains several original buildings, including a barn, the quarters where enslaved families lived and the Bennehan house. The exhibition, which showcased Freelon’s signature tissue-paper sculptures, drew upon Library materials and other archival images to honor and reimagine the lives of enslaved Black children.

Freelon’s pieces were located throughout the Bennehan house and inside a large timber-framed barn on the property. Portraits of children in the home hold special meaning for Freelon, who wanted to uplift them “in an actual home they weren’t even allowed in.” One tissue-paper sculpture contained printed names of the more than 200 Black children who lived at Stagville.

As a 2024 Library of Congress Connecting Communities Digital Initiative artist/scholar in residence, Freelon researched Library collections seeking 19th-century images of Black children that represented “innocence, beauty, light and love amidst a terrible situation.”

Her search often was difficult. Images of Black children in joyous moments during this period are rare, pushing Freelon to expand her search criteria. Occasionally, she would make a discovery in the Prints and Photographs Division, like a 1900 photo of a young Black girl smiling while holding flowers.

This photo, taken around 1900, inspired artist Maya Freelon in her work, seen below. Photographer unidentified; possibly by Rudolf Eickemeyer, Jr. Prints and Photographs Division.

This photo, taken around 1900, inspired artist Maya Freelon in her work, seen below. Photographer unidentified; possibly by Rudolf Eickemeyer, Jr. Prints and Photographs Division.The exhibition opening’s theme was “play,” evoking the innocence of children held in bondage. Attendees, including descendants of people once enslaved on the plantation, participated in childhood games such as “Down by the River” and “Miss Mary Mack.”

The opening event was a collaborative offering. Nnenna Freelon, the artist’s mother and a well-known jazz singer, sang nursery rhymes and invited attendees to accompany her with instruments. In the barn, Allie Martin, an ethnomusicologist at Dartmouth College and Freelon’s fellow 2024 CCDI artist/scholar in residence, presented a motion-activated soundscape. By entering the building, attendees could play different noises, from Martin’s vocals to wind from the cemetery where Martin’s grandmother is buried, transforming the barn into an instrument.

Freelon’s work centers Black children navigating unimaginable circumstances during enslavement. Her artwork recognizes them, memorializes their experiences and highlights their innate joy.

Maya Freelon’s “Beautiful Flower,” inspired by the photo above. Prints and Photographs Division.

Maya Freelon’s “Beautiful Flower,” inspired by the photo above. Prints and Photographs Division.“Whippersnappers” was part of the North Carolina Division of State Historic Sites Art on the Land initiative, which seeks to build connections to sites of memory through artistic collaborations, installations and gatherings.

“‘Whippersnappers’ brings these images out of the silence of the archive into a contemporary moment where the viewer can imagine more just futures,” said Johnica Rivers, NCHS curator at large.

Projects like Freelon’s, which ran through January 2025, honor the experiences of Black communities while showcasing Library materials to new audiences.

Since 2022, the Mellon-funded CCDI has supported individuals and institutions in exploring the Library’s digital collections and highlighting the perspectives of Black, Indigenous, Hispanic/Latino, Asian American and other communities of color.

“Maya Freelon’s powerful offering to our youngest ancestors,” NCHS Director Michelle Lanier says, activated “a posture of healing through reclaiming and reframing memory.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 25, 2025

World War I: Two Soldiers’ Stories

—This is a guest post by Nathan Cross, an archivist in the Veterans History Project.

As far as we know, Arthur Singleton and Jessie Lockett did not know each other when they arrived in France with the American Expeditionary Forces in autumn 1918.

Their fates intertwined years later, when their families united through the marriage of Lockett’s son to Singleton’s daughter — and again in 2024, when their mutual granddaughter donated their manuscript collections to the Veterans History Project.

The Singleton and Lockett collections are the Veterans History Project’s first from African American veterans of World War I, and their letters, journals and photographs offer glimpses into the adversity and resilience that characterize the African American experience of that war.

As his journal shows, Singleton, a sergeant in Company E of the 803rd Pioneer Infantry Regiment, was a leader in both military matters and his unit’s social and intellectual life. He joined a literary society, sang in theatrical performances and co-founded a soldiers’ fraternal organization called the Seven Brothers Club. The journal also reveals racist treatment he and his comrades faced: A canteen run by a charitable organization denied them service, and taunts greeted them at another unit’s theatrical performance. His company entered the front lines at 5 a.m. on Nov. 11, 1918, and manned the trenches until the war-ending armistice went into effect at 11 a.m.

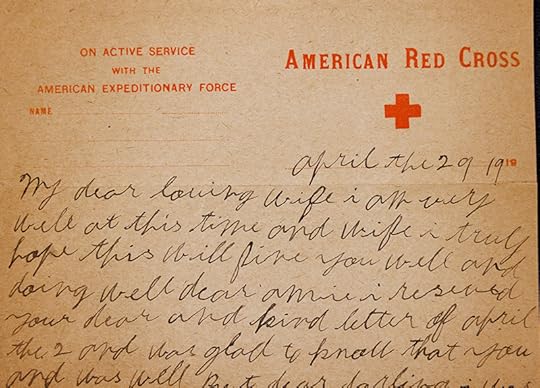

Jessie Lockett wrote this letter to his wife, Amanda, on April 29, 1919. Veterans History Project.

Jessie Lockett wrote this letter to his wife, Amanda, on April 29, 1919. Veterans History Project.Lockett served as a stevedore, undoubtedly hazardous and difficult duty. His letters home, however, make clear that his separation from spouse Amanda Lockett was the most difficult aspect of his deployment. The couple ran a small farm in Georgia, and their letters hint at the financial difficulties caused by Jessie’s time away. But it’s the emotional toll that comes through most vividly: Jessie repeatedly reminds Amanda how much he misses her and cherishes her “sweet letters.”

The Lockett and Singleton collections serve as two more examples of how treasured family papers and photographs provide us all with a more personal understanding of the American military experience.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 17, 2025

Ryan White and Elton John: One Stunning Photo

—This is a guest post by Adam M. Silvia, a curator in the Prints and Photographs Division.

As a photojournalist, Taro Yamasaki photographed at-risk children in the United States and around the world — Nicaragua, Bosnia, Rwanda, the Middle East.

The Prints and Photographs Division recently acquired three collections that document such work by the Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer: “Children in Peril,” “Escaping Human Trafficking” and “Ryan White and the Battle Against AIDS” — the last a chronicle of the American teenager who became an international symbol of the fight against the disease.

People magazine had hired Yamasaki and reporter Bill Shaw to contribute to a special feature on living with AIDS, along with other teams in major cities across the U.S. The pair arrived at White’s home in Cicero, Indiana, in summer 1987 to begin work.

“I hadn’t met or photographed anyone with AIDS, though I was reading everything I could find about it,” Yamasaki recalled in an interview with the Library’s Picture This blog about his influential photographs of White.

White, then 15 years old, was born with hemophilia and contracted AIDS from a tainted blood transfusion. The local school refused to readmit White to classes after other parents objected, incorrectly believing the disease might spread to other students.

Yamasaki describes meeting White for the first time, photographing his struggle and witnessing his miraculous transformation into an ambassador of sorts, inspiring empathy for the victims of AIDS. Upon hearing his story, pop superstar (and future Gershwin Prize winner) Elton John befriended White and his family. White died in 1990, at age 18. Just after he passed, family and friends gathered in a circle for prayer.

“They held hands, and (White’s mother) Jeanne said, ‘You can photograph this or you can join the circle, Taro,’” Yamasaki said. “I put my camera down and joined the circle, knowing full well that my editors would have wanted that picture.”

At the funeral, Yamasaki took one of his greatest photographs, capturing the power of White’s story. With permission, Yamasaki hid behind the piano as John performed “Skyline Pigeon.”

“In the middle of the song, I stood up,” he remembered, “hoping my hands weren’t shaking too much to get a sharp picture.” It was the perfect photograph.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 13, 2025

The Library Turns 225!

—This is a guest post by April Slayton, a former director of communications at the Library.

How it started: When Congress established the Library of Congress in 1800, it provided $5,000 and purchased a collection of 152 works in 740 volumes and three maps for the use of its members. A joint committee selected the books and organized the volumes themselves when they arrived from London.

How it’s going: 225 years later, the Library has amassed what is widely considered the greatest collection of knowledge ever assembled. And, while Congress remains the Library’s first audience, the Library also reaches millions of people around the world, who now have access to its unparalleled resources.

Along the way, the Library endured two catastrophic fires in its early days that decimated its collections; assumed responsibility for all U.S. copyright administration; acquired vast collections that are the envy of the world; provided evermore sophisticated service to Congress; established itself as a leader in the field of librarianship; and grew its reach in the digital age.

Still, in the beginning, the Library was a modest institution. It wasn’t until 1802 that it had any staff of its own, and then only on a part-time basis. President Thomas Jefferson appointed John James Beckley, who also served as the clerk of the House of Representatives, as the first Librarian of Congress. He was assisted by Josias Wilson King, the engrossing clerk of the House in the effort to “label, arrange and take charge of the (Library’s) books.”

By 1812, that collection had grown to about 3,000 volumes, but all were lost in the fire set by the British at the U.S. Capitol in August 1814. It was after this tragedy that the Library’s acquired its new foundation — the library of Jefferson, by that time a former president. In 1815, Jefferson sold his 6,487-volume collection to the U.S. government for $23,950 to help the Library begin again. As the Library took ownership of Jefferson’s collection, it also assumed his vision that there was “no subject to which a Member of Congress might not have occasion to refer.”

A second fire in the U.S. Capitol on Christmas Eve in 1851 destroyed around 35,000 volumes in the Library, including about two-thirds of Jefferson’s library. As the Library reckoned with this tragedy, Congress authorized a fireproof iron room on the Capitol’s west front to house the Library.

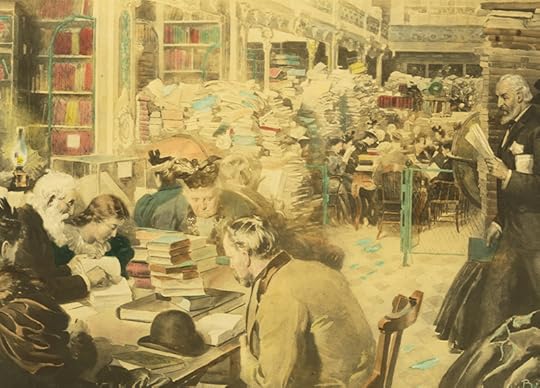

A print showing a busy day in the Congressional Library in the Capitol Building. Illustration by drawing by W. Bengough in Harper’s Weekly, Feb. 27, 1897. Prints and Photographs Division.

A print showing a busy day in the Congressional Library in the Capitol Building. Illustration by drawing by W. Bengough in Harper’s Weekly, Feb. 27, 1897. Prints and Photographs Division. In the years that followed, the centralization of copyright administration at the Library in 1870 led to a flood of new content for the Library’s collections, which soon outstripped its available space in the Capitol. This influx of material, coupled with the haunting experience of two destructive fires, propelled efforts to establish a stand-alone building to house the Library.

And what a building it was. The monumental new “book palace” known today as the Thomas Jefferson Building opened to the public in 1897. It boasted 104 miles of shelves beyond the dazzling public spaces that captivated visitors from the moment it opened.

In 1897 on the occasion of its grand opening, the Washington Post reported, “In construction, in accommodations, in suitability to intended uses, and in artistic luxury of decoration, there is no building that will compare with it in this country and very few in any other country.”

The original keys to the Jefferson Building. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The original keys to the Jefferson Building. Photo: Shawn Miller.Additional buildings followed: the John Adams Building in 1939, the James Madison Building in 1980 and the Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation in 2007. Each of these spaces provided more capacity for the burgeoning collections and offered more accommodations for staff and library patrons.

Alongside the growth in its physical presence, the breadth of the Library’s work grew as well.

The Library acquired important works and collections through gifts from other countries and civic-minded donors. Philanthropic donations have enhanced the Library’s collections for much of its history, including Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge’s 1925 gift and endowment that funded the construction of the Coolidge Auditorium in the Jefferson Building and established the Library as a premier destination for the study, composition and enjoyment of music.

In 2007, David Packard’s record-breaking gift of the $155 million Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation provided state-of-the-art facilities for the world’s largest and most comprehensive collection of moving images and sound recordings and boosted the Library’s status as a global leader in film and sound preservation and accessibility.

Today, the Kislak Family Foundation and the Library’s Madison Council, led by philanthropist and co-executive chairman of the Carlyle Group David M. Rubenstein, have provided leading gifts that are creating exciting new galleries, experiences and learning spaces for Library visitors.

In the 1960s, the Library established overseas offices to expand its authoritative international collections that began in the Library’s early days with gifts and purchases of works from foreign nations and documents acquired through international exchanges.

Today, a network of six overseas offices collects and catalogs materials around the world, continuing the growth of the Library’s extensive international collections.

The Library faced challenges even in its early days to organize its growing collections. From the development of the Library of Congress Classification System in the early 1900s to the creation of Machine-Readable Cataloging that enabled computerized searches of catalog information, the Library created the systems now used around the world to organize collections.

A hallway in the Jefferson Building on a recent day. Photo: Shawn Miller.

A hallway in the Jefferson Building on a recent day. Photo: Shawn Miller.Today, virtual visitors can access millions of items on the Library’s website in dozens of formats and hundreds of languages. Online collections offer the opportunity to explore maps and photographs; read letters, diaries and newspapers; hear personal accounts of events; listen to sound recordings and watch historic films on demand, anytime and anywhere.

This mind-boggling growth — from a catalog of 740 volumes and three maps available only to lawmakers to a collection of more 181 million items available to the world — could not have happened without the dedicated people who have worked for the Library over its 225-year history.

During that time, the Library has developed a cadre of specialists and experts. They have developed the Legislative Reference Service established of 1914 into the Congressional Research Service of today. They have acquired, catalogued, organized and preserved vast collections and provided research assistance to all who ask for help. They have administered the complex laws governing copyright and supported the protection of creative works. They have produced award-winning programs and events that inspire people and bring new works of music, art and literature into the world.

In fiscal year 2023 alone, Library employees responded to more than 680,000 reference requests from Congress, other federal agencies and members of the public. They circulated more than 249,000 items used by patrons, issued more than 63,000 reader cards and offered more than 700 public programs. They responded to more than 76,000 congressional requests, published nearly 1,200 CRS products and updated more than 1,800 existing CRS products.

In the next 225 years, the Library will certainly see prodigious growth in its already vast collections, but even as technology and other conditions change the world, the Library’s place as a global leader in knowledge preservation and access will endure, propelled by the talented public servants who dedicate their talents and efforts to this grand institution.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 10, 2025

Josephine Baker at the Stork Club: A Night Gone Wrong

The stormy affair of Josephine Baker at New York’s splashy Stork Club in the fall of 1951 was a brief-but-infamous incident and now a fascinating part of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund collection at the Library.

Baker’s angry showdown over an apparent race-based refusal of service at New York’s most exclusive club fills hundreds of pages of documents that show how the tempestuous star whipped up a high-profile protest in an era before segregation was nationally outlawed — only to see it go terribly wrong.

“She had it in her hands, everything she wanted,” Jean-Claude Baker wrote of his legal guardian/mother his 1993 biography, “Josephine: The Hungry Heart,” referring to her career decline that accelerated with the Stork Club incident. As her manager in the last decade of her life, he knew this terrain well. “And she blew it.”

You can see the LDEF’s files on Baker now from any computer anywhere. About 80 percent of the LDEF’s collection recently has been digitized, about 80,000 items from 1915 to 1968. This puts the Baker material alongside the civil rights organization’s nation-changing work in matters such as Brown v. Board of Education, the 1943 Detroit riot, the Emmett Till trial and many more cases of segregation and voting rights.

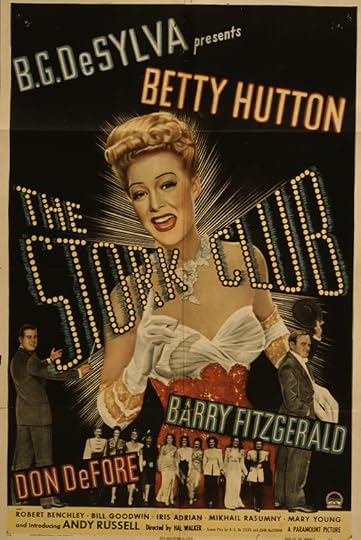

“The Stork Club,” a 1945 Paramount Pictures film starring actress Betty Hutton, catches the club’s glamorous reputation. Image: Prints and Photographs Division.

“The Stork Club,” a 1945 Paramount Pictures film starring actress Betty Hutton, catches the club’s glamorous reputation. Image: Prints and Photographs Division.Baker’s night at the Stork Club (which did not serve Black customers unless they were celebrities, and not always even then) was on Oct. 16, a Tuesday. She entered the club near midnight after her show at the Roxy Theatre. She was with three socially prominent friends, both Black and white.

She made sure to say hello to Walter Winchell, the nation’s most popular newspaper and radio columnist, on the way to her table. He had fawned in print and on air about Baker’s segregation-busting appearance in Miami Beach’s Copa City Club months earlier. The Stork, owned by his friend Sherman Billingsley, was his night office.

Baker was one of the most famous women in the world that night, and arguably the most famous Black woman. She had overcome childhood poverty in St. Louis to become, at 19, an overnight Parisian sensation in “La Revue nègre” and starred the next year at the Folies-Bergére. She danced wearing little more than a skirt of fake bananas and several beaded necklaces. That risqué image of her became an iconic representation of the Jazz Age and the Roaring Twenties.

It also catapulted her to international stardom as a multilingual singer, dancer, actress and performer. A temperamental diva onstage and off, she settled in France, became a citizen and gained gravitas by serving as a secret agent in World War II, for which she was highly decorated and greatly respected.

That night at the Stork, Baker’s party, leaving Winchell at his famous Table 50, was seated six or seven tables over and served drinks. Baker ordered a meal a few minutes later — steak and crab — but it was not served. Baker’s party was ignored by waiters. An hour passed.

Baker, fuming, left the dining room and called Walter White, executive secretary of the NAACP. When she returned, her food was on the table, but she refused to eat it. Angry words were exchanged; Baker’s party stormed out.

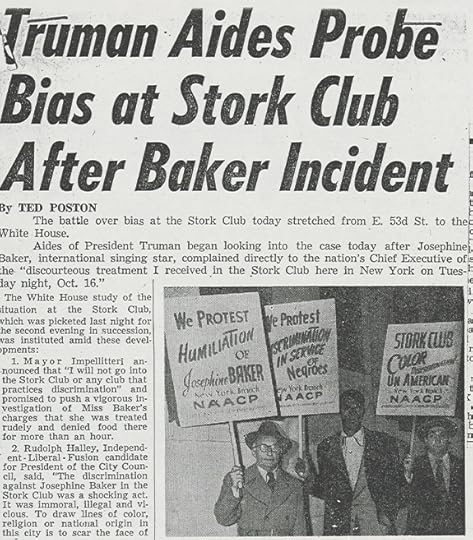

Baker was so famous in 1951 that President Harry Truman ordered an investigation of her treatment at the New York nightclub. New York Post, Oct. 24, 1951. Manuscript Division.

Baker was so famous in 1951 that President Harry Truman ordered an investigation of her treatment at the New York nightclub. New York Post, Oct. 24, 1951. Manuscript Division. The LDEF, led by White, mobilized support. Baker wrote President Harry Truman, who told aides to investigate. New York Mayor Vincent R. Impellitteri said he would not “go into the Stork Club or any club that practices discrimination” and his Committee on Unity launched an investigation. Boxer Sugar Ray Robinson, a huge star, entered the fray on Baker’s behalf. The American Jewish Congress asked the city to pull the club’s liquor license. Picket lines showed up outside the Stork.

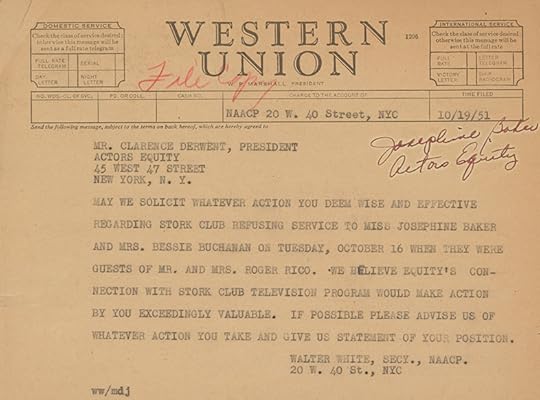

White telegraphed the influential Actors’ Equity Association in New York: “May we solicit whatever action you deem wise and effective,” he wrote. “… We believe Equity’s connection with Stork Club television program would make action by you exceedingly valuable.”

Telegram from Walter White of the NAACP requesting the Actors’ Equity Association put pressure on the Stork Club. Manuscript Division.

Telegram from Walter White of the NAACP requesting the Actors’ Equity Association put pressure on the Stork Club. Manuscript Division. Billingsley shot back in a terse one-pager to White that his club had always excluded “obnoxious” patrons and always would. It left little doubt in this context that “obnoxious” meant “Black.”

If Baker had just gone after the Stork Club, it’s likely she would have carried the day. In a 2000 book, “Stork Club: America’s Most Famous Nightspot and the Lost World of Café Society,” New York Times reporter and author Ralph Blumenthal wrote that the Baker scandal broke club’s charm and made it look like an anachronism. By 1965, it was out of business and broke. A year after that, Billingsley was dead of a heart attack.

Still, in 1951, Baker inexplicably had made a fatal mistake: She said that Winchell, who had often supported liberal causes, witnessed the entire spectacle and did nothing. This was likely not true — even a member of Baker’s party said Winchell had left before the incident’s ugly conclusion — and an escalation of catastrophic proportions.

Winchell took to print and the airwaves, telling his nationwide audience that he admired Baker but had indeed left before the incident. “I am appalled at the agony and embarrassment caused Josephine Baker and her friends at the Stork Club,” he said. “But I am equally appalled at their efforts to involve me in an incident in which I had no part.”

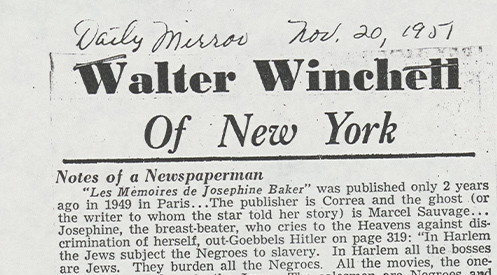

Walter Winchell struck back at Baker with this devastating article, quoting from her memoir. New York Daily Mirror, Nov. 20, 1951. Manuscript Division.

Walter Winchell struck back at Baker with this devastating article, quoting from her memoir. New York Daily Mirror, Nov. 20, 1951. Manuscript Division.An infamously vicious man when angry, he went after Baker. He dug up her 1949 memoir (published in France) in which she had written derogatively about American Jews. He dug up older clips, showing that she had been a prewar fan of the fascist dictator of Italy, Benito Mussolini. He whispered she might actually be a communist — a career-killing charge in the Cold War era.

Baker wasn’t cowed. The next week, in a handwritten letter on hotel stationery, Baker wrote White, saying that if she got her life story published, “all the money would come to the NAACP you must have money to carry on. I will sign the contract in the name of the NAACP.”

By early December, Baker’s attorney, Arthur Garfield Hays, co-founder of the American Civil Liberties Union, was writing that the case was a symbolic moment for the nation.

The affair involved “issues much bigger than either Miss Baker or Mr. Billingsley,” he wrote. “… The real question is whether laws which provide against discrimination are to be enforced or are to be ignored.”

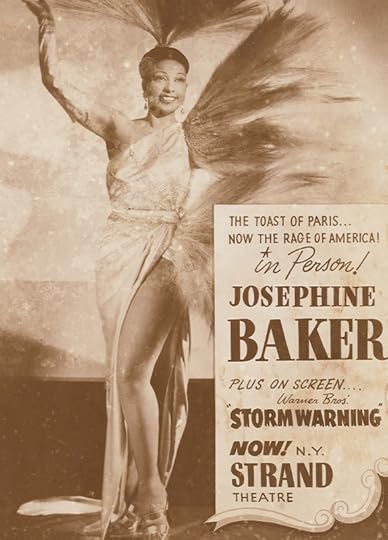

A promotional poster for Baker’s appearance at the Strand Theater in New York in 1951. Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

A promotional poster for Baker’s appearance at the Strand Theater in New York in 1951. Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.He also tried to slip in an apology to Winchell, saying that Baker now “accepted” that he had left the club before the incident, but it was far too little too late.

Baker had overplayed her hand. Winchell had badly damaged her reputation. The Mayor’s Committee on Unity, so eager to jump into the fray in October, dismissed the case in December, saying there was no evidence of a “charge of racial discrimination.”

White, the NAACP leader, was furious in his response: “Evidently your committee failed to probe into the Stork Club’s longstanding policy of excluding Negroes.”

Baker only made it worse, lambasting the U.S. while continuing her tour across the U.S. and Latin America, losing more friends and concert bookings in the process.

She remained undaunted, but her star was diminished. She spoke at the March on Washington in 1963 and in 1975 enjoyed a return to top-tier limelight with a comeback show in Paris. She died of a cerebral hemorrhage during the show’s run. She was 68.

Baker is today widely celebrated on any number of fronts, as her titanic personality far exceeded the world of entertainment. A U.S. stamp was issued in her honor in 2008. In 2021, she was honored with a memorial inside the Pantheon, France’s national mausoleum, the first Black woman to be so recognized.

“France is Josephine,” French President Emmanuel Macron said during the ceremony.

In her short speech at the March on Washington, Baker delivered a line that, over the years, has come to explain much about her career, including that night at the Stork Club.

“I have walked into the palaces of kings and queens and into the houses of presidents, and much more,” she told the crowd of some 250,000. “But I could not walk into a hotel in America and get a cup of coffee, and that made me mad. And when I get mad, you know that I open my big mouth.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 7, 2025

Stylish Posters for the National Cherry Blossom Festival

—This is a guest post by Mari Nakahara and Katherine Blood, librarians in the Prints and Photographs Division. It also appears in the March-April issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

From saplings to centenarians, the fabled cherry blossom trees of Washington, D.C., entice more than 1.5 million visitors to the capital each spring. The initial 1912 gift of 3,020 cherry trees from the city of Tokyo to Washington launched such treasured and enduring traditions as the National Cherry Blossom Festival (Sakuramatsuri in Japanese), which officially began in 1927 and continues to this day.

The Library has collected and preserved each commissioned festival poster since 1987. These artist-designed images reflect on natural beauty, international friendship between Japan and America and local and global communities coming together. Inspired by the glowing blossoms, pink is almost always involved!

Posters engage viewers quickly through combinations of eye-catching art, thoughtful graphic design and compelling messaging. Also functioning as travel posters, these images often pair cherry blossoms and trees with famous D.C. landmarks — the Jefferson and Lincoln memorials, the Washington Monument or the U.S. Capitol.

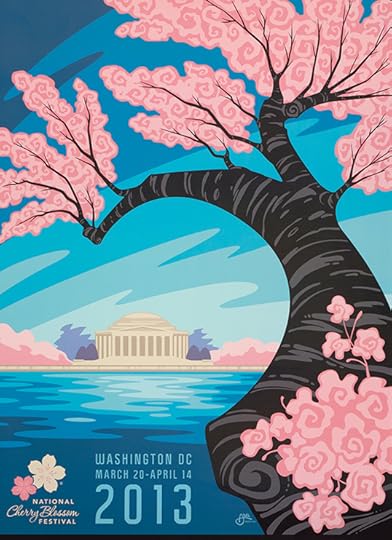

The 2013 National Cherry Blossom Festival poster. Artist: Erik Abel.

The 2013 National Cherry Blossom Festival poster. Artist: Erik Abel.Strong parallels are seen in the Library’s collection of travel posters from Japan, where cherry blossoms are part of cultural life as poignant symbols of beauty and transience. Those posters frequently depict Hanami (blossom-viewing) destinations or show admirers delighting in the beauty of flourishing yet delicate blossoms.

You can enjoy cherry blossoms all year round in the Library’s extensive collections related to sakura (cherry blossoms), including historical and contemporary prints, drawings, photographs, ephemera and more, created from the 19th century forward by Japanese, American and international artists. And all are featured in the Library’s popular 2020 book (going into its second edition in 2025) “Cherry Blossoms: Sakura Collections from the Library of Congress.”

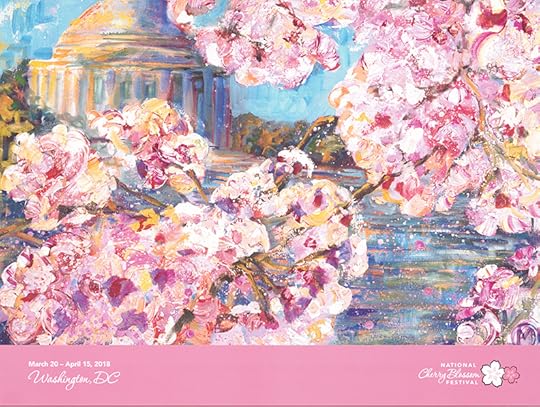

The 2018 National Cherry Blossom Festival poster. Artist: Maggie Elizabeth O’Neill.

The 2018 National Cherry Blossom Festival poster. Artist: Maggie Elizabeth O’Neill.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

March 6, 2025

Checking in with Einstein Fellow Jessica Fries-Gaither

Jessica Fries-Gaither, an elementary school science teacher from Columbus, Ohio, is serving as an Albert Einstein distinguished educator fellow at the Library this year.

Tell us about your background.

I’ve been a science educator for the past 25 years. During that time, I’ve taught in several states (Tennessee, Alaska and Ohio); in public, private and independent schools; across different grades (first through eighth); and at the graduate level.

I also spent a few years out of the classroom, serving as project manager on National Science Foundation-funded grants dedicated to helping elementary and middle school teachers improve their science teaching and integrate literacy into their classes.

Most recently, I was the Science Department chair and Lower School science specialist at Columbus School for Girls in Columbus, Ohio.

Outside of teaching, I’m also an author. I’ve published three books for science teachers and four science-themed children’s books, and I have many more manuscripts in various stages of the writing and publishing process.

Of course, my time at the Library has greatly increased my list of possible projects!

What inspired you to come to the Library as an Einstein fellow?

I spent a lot of time visiting my public library and reading books as a child, so I suppose there’s always been a natural connection there.

But my real inspiration came from attending the Library’s Teaching with Primary Sources summer workshop in July 2023. Between the thoughtful facilitators (Cheryl Lederle, Michael Apfeldorf and Celia Roskin), the intriguing primary sources and the rich conversations among my cohort members, I was hooked.

I went back to my hotel that first evening and told my husband, “I found my people!”

I knew that the Library hosted Einstein fellows, and so I began the application process shortly after returning home to Columbus. I’m thankful that Lee Ann Potter of the Professional Learning and Outreach Office and Monica Smith of the Informal Learning Office agreed that this would be a great fit for me.

What resources at the Library have captivated you so far?

There have been so many that it’s hard to know where to begin.

Maria Merian’s gorgeously illustrated 1705 book on the insects of Suriname has been one of my favorites. I’ve worked on a fascinating project with Cindy Connelly Ryan and others in the Preservation Research and Testing Division (PRTD) about it.

And I’ve taught students about Marie Tharp mapping the ocean floor. So, seeing the Heezen-Tharp world ocean floor map in the Geography and Map Division was incredible.

But I’ve also really loved discovering lesser-known documents and individuals. Josh Levy of the Manuscript Division shared a mock picture book that astronomer Vera Rubin created in the hopes of selling (but never did). And, together, we combed through the papers of Mira Lloyd Dock, an important Progressive Era forester I had never heard of until my time at the Library.

As an author, I really enjoyed meeting with Jackie Coleburn of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division and seeing creative and innovative historical children’s books.

Ultimately, though, while the collections in the Library are fascinating, the truly remarkable resources are the people who have generously shared their time and expertise to make this fellowship experience so rich.

How will your Library residency affect your approach to education?

My time at the Library has strengthened my research skills and reminded me just how joyful the research process can be.

Too often, research is presented to students as a prescriptive and mundane task, leading kids to check off the boxes instead of pursuing a question with curiosity and determination. I’d like to think about (and try out) different approaches to helping kids build the skills they need to be successful researchers while also preserving the wonder and satisfaction that comes from a completed project.

What would you like science educators to know about the Library?

Above all, I’d like my fellow science educators to have a sense of the breadth and depth of the relevant resources in the Library’s collections and understand how collection items can complement and enhance the great work they are already doing. I’ve tried to write blog posts in a way that connect the Library’s sources to the framework that science teachers use in their classrooms, and my upcoming presentations at the National Science Teaching Association will share the same message.

Through my work with PRTD, I’ve also learned so much about the ways in which scientific techniques and analysis contribute to cultural heritage science. This was entirely new for me, and I know that educators and their students would benefit from learning about these applications and careers.

Who knew X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, one of the techniques PRTD uses to analyze materials, would be a useful tool at a library?

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

February 24, 2025

Thomas Jefferson’s Library…

In September 1814, Thomas Jefferson wrote one of the more important letters in American history to his friend Samuel H. Smith, a longtime friend and prominent academic and newspaper publisher. Jefferson, furious that British troops had burned the U.S. Capitol a few weeks earlier, asked Smith to act as an intermediary and offer his immense book collection to Congress to replace the in-house library that had been torched.

Smith did so and Jefferson sold Congress 4,931 titles (encompassing 6,487 volumes) for $23,950 the next year, forming the DNA of today’s Library of Congress, now the largest library in the world. Jefferson’s books were seen as working copies at the time, quickly added to and moved about and soon, tracking where his actual books were become difficult to assess. Then, after an 1851 Christmas Eve fire in the Congressional Reading Room destroyed 3,000 or so of Jefferson’s original volumes, all hope of preserving or recreating his original library seemed lost.

Ever since, reconstructing Jefferson’s “catalogue at this moment” has been a quest, a fascination and an obsession for scholars. Jefferson had written out his own bibliographies of his collections, as have later experts such, as E. Millicent Sowerby’s magnificent one compiled in the mid-20th century.

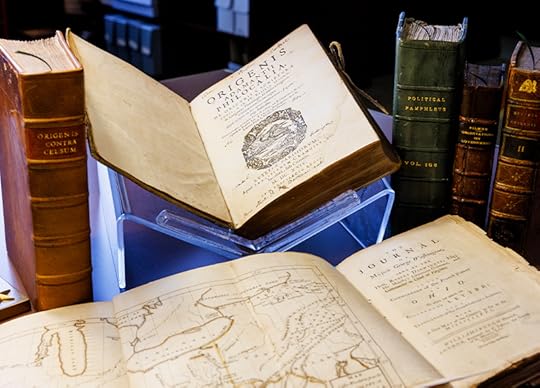

Today, at the Library’s 225th anniversary, after 27 years of international work anchored by a million-dollar grant from Jerry and Gene Jones and carried out by some of the Library’s most accomplished experts, the fire-damaged collection is still slightly “garbled” but almost entirely complete. Two hundred or so minor volumes and pamphlets now may be lost to time, such as an Italian pamphlet on pomegranate growing that the ever-curious Jefferson had tucked away.

Jefferson’s library contained books, maps and pamphlets in several languages. Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Jefferson’s library contained books, maps and pamphlets in several languages. Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.The Library’s staff on the project has examined its own collections, other libraries, rare book dealers and antiquarians from multiple countries to replace the burned and missing volumes with exact copies — the same edition, publisher and so on — to replicate the world view that led the author of the Declaration of Independence to pen such a world-changing set of ideas.

“The project is not so much about finding an individual book,” said Mark Dimunation, the former chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division who spearheaded the effort. “It’s the collection itself, because it really is the universe of his creative knowledge. All of the books are atoms in that larger universal structure. And they all had weight with him.”

Jefferson was fluent in several languages and he let his curiosity go where it might. He later wrote a friend, describing the books that would become the foundation of the Library of Congress.

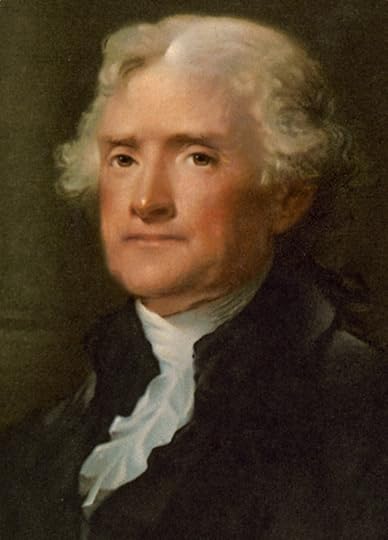

Thomas Jefferson. Photo detail from a Gilbert Stuart portrait at Bowdin College-Brunswick, Maine.

Thomas Jefferson. Photo detail from a Gilbert Stuart portrait at Bowdin College-Brunswick, Maine.“While residing in Paris I devoted every afternoon I was disengaged, for a summer or two, in examining all the principal bookstores, turning over every book with my own hands, and putting by every thing which related to America, and indeed whatever was rare & valuable in every science,” he wrote. “besides (sic) this, I had standing orders, during the whole time I was in Europe, in it’s (sic) principal book-marts, particularly Amsterdam, Frankfort, Madrid and London, for such works relating to America as could be found in Paris.”

So while his was an American collection, it was composed mostly of European parts, brought together from many places at many different times, purchased by many different people.

There were some glorious copies Jefferson owned – he had more than 40 volumes by Marcus Tullius Cicero, his favorite classical philosopher; his annotated copies of The Federalist; George Sale’s translation of the Koran, as he was always exploring religion; and of course he had Blackstone’s “Commentaries on the Laws of England” – but he often preferred workaday reading copies of later editions, to save costs (he was always in debt) and to have access to the latest information.

Since these later editions were never very remarkable, few antiquarians ever saw the need to hold onto them, and most are just gone.

“One aspect of Jefferson’s collecting was to pick up things that weren’t common – things mistakenly described as ‘pamphlets’ that were really just tearaway chapters from books,” Diminution says. “There’s just a whole variety of scarce materials that can’t be located in matching copies today. And there are few titles that we can find no bibliographic evidence of whatsoever.”

But a few times a year, a matching book is discovered. In 2024, donor Marianne Spain came across the sixth edition of “Elémens de l’histoire de France, depuis Clovis jusqu’à Louis XV” by abbé Claude François Xavier Millot. It’s a three-volume set, published in Paris in 1787. She recognized it as a Jefferson match and donated it to the Library. It’s now in the Jefferson Library exhibit – just another small moment of serendipity and philanthropy bringing Jefferson’s completed library one step closer to reality.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers