Library of Congress's Blog, page 4

June 9, 2025

Sir Francis Drake & The Elizabethan World

The captain set sail with five ships and 164 crew members from Plymouth, England, at 5 p.m. in the early darkness of Dec. 13, 1577. The ships headed south and vanished from sight.

He didn’t return for nearly three years, sailing back into Plymouth with only a fraction of his fleet intact. But he had the hold of his last ship “very richly fraught with gold, silver, pearls and precious stones.” In today’s terms, the cache was worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

He also had the world at his feet, for Francis Drake — soon to be Sir Francis Drake — was the first captain to sail around the world and live to tell about it. (Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan was killed during the world’s first circumnavigation half a century earlier; his crew finished the trip.)

But Drake! How he lorded over the seas!

This detail from a map of St. Augustine is from one of Drake’s earlier voyages. It features an outsized dorado fish (today known as Mahi-mahi), showing how struck explorers were with the new worlds they were encountering. Artist: Baptista Boazio. Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

This detail from a map of St. Augustine is from one of Drake’s earlier voyages. It features an outsized dorado fish (today known as Mahi-mahi), showing how struck explorers were with the new worlds they were encountering. Artist: Baptista Boazio. Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Photo: Shawn Miller. He was in his early 40s then, the swashbuckling man of action in 16th-century England, rocketing from the rural working class to being a wealthy confidant of Queen Elizabeth and one of the most influential explorers in world history. He circled the globe, raided Spanish ports and ships from Europe to the Caribbean with wild abandon, helped defeat the Spanish Armada, claimed California for the queen and rescued the first British settlers in North America on Roanoke Island. Less admirably, he was an early slave trader and helped lead the English massacre of some 500 men, women and children on Ireland’s Rathlin Island.

Let’s get a look at him up close:

“He is low in stature, thick-set, and very robust,” reported Nunho da Silva, a Portuguese pilot Drake captured and forced into service for part of the round-the-world trip. “He has a fine countenance, is ruddy of complexion and has a fair beard. … He is a great mariner, the son and relative of seamen.”

Nearly 450 years later, Drake’s world-changing exploits are preserved at the Library in a stunning collection of contemporary maps, charts, historical accounts, letters and correspondence in several languages, many of them rare or the only copies known to exist.

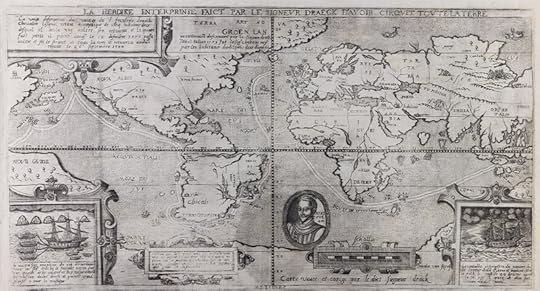

This includes one of the treasures of the age, the Nicola van Sype map of Drake’s circumnavigation, the earliest printed map of the expedition. It’s likely a smaller version of the map that Drake gave Queen Elizabeth shortly after his triumphant return on Sept. 26, 1580. Since that larger map, known as the Whitehall Map, was lost years later (likely in a fire), this is the earliest map of the voyage still in existence.

This Nicola van Sype map is the oldest surviving map of Drake’s round-the-world voyage. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

This Nicola van Sype map is the oldest surviving map of Drake’s round-the-world voyage. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.The collection brings it all breathing back to life, this Elizabethan world of exploration when no one knew what the planet fully entailed, when rumors of hidden continents and waterways abounded, sea monsters were said to swarm up from the deep, when entire continents of peoples had no little or no contact with one another.

One of the most famous parts of the voyage came when Drake dropped the anchor of his ship, the Golden Hind’s (or Golden Deer, in today’s language) at what is now Point Reyes National Seashore, about 30 miles north of San Francisco. They stayed for about six weeks.

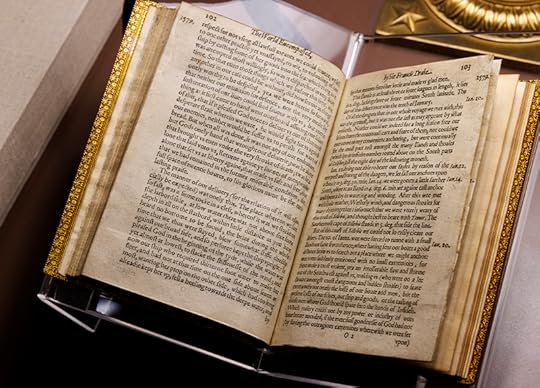

The Coast Miwok people had long lived there, but Drake and his crew claimed the area to be New Albion, as Albion was the classical name for England. They marveled at the strange climate: “… in the middle of their summer, the snow hardly departeth even from their very doors, but is never taken from their hills at all; hence come those thicke mists and most stinking fogges [fogs],” wrote Francis Fletcher, the voyage’s chaplain, in “The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake,” the first full narrative of the voyage. “… but the nipping cold … meeting and opposing the Sunne’s endeavor, forces him to give over his work.”

A first edition of “The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake,” published in 1628, is preserved at the Library. Photo: Shawn Miller. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

A first edition of “The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake,” published in 1628, is preserved at the Library. Photo: Shawn Miller. Rare Book and Special Collections Division. From there, Drake set sail across the vast Pacific, past Asia, across the Indian Ocean, around Africa and back to Plymouth.

The Library’s collection was assembled by Hans Peter Kraus, one of the most important antiquarian book dealers of the 20th century, and his wife, Hanni. The Jewish couple fled Austria in 1939 as World War II approached and Nazis seized his rare book business. The couple settled in New York, where Hans resumed his trade. He was fascinated by Drake, he said, after he learned of how the incredible wealth he brought back to England helped establish the nation as a global empire.

“I wanted to gather only original and contemporary sources, in printed books, in autographs and manuscripts, in maps, in portraits, or in medals,” he said in a 1968 lecture at the University of Minnesota. “The motive for my collecting was to learn about Drake in the same way as anyone living in Europe during his lifetime would have done.”

For all his high-flown adventures, the great mariner did not live a long and happy life. He had no children, and though he was married, lived in comfort on a huge estate and served as the mayor of Plymouth, he eventually returned to sea-faring adventures.

A 1588 Dutch silver medal commemorating England’s stunning defeat of the Spanish Armada, in which Drake played a part. Photo: Shawn Miller. Prints and Photographs Division.

A 1588 Dutch silver medal commemorating England’s stunning defeat of the Spanish Armada, in which Drake played a part. Photo: Shawn Miller. Prints and Photographs Division.It did not go well. A 1589 raid on Spain was a dismal failure, enraging the queen. In 1596, after a series of failed raids on Spanish forts along the coasts of modern-day Colombia and Panama, he fell ill with fever and dysentery. He lingered for two weeks. Just after 4 a.m. on Jan. 28, not far off the coast of modern-day Portobelo, Panama, he came to his final hour.

As the ship’s journal has it: “… our Generall sir Francis Drake departed this life, having bene extremely sicke of a fluxe. … He used some speeches at or a little before his death, rising and apparelling himselfe, but being brought to bed againe within one houre died.”

The British hero of the age was about 56 (the year of his birth was never certain). He was buried at sea in a lead coffin. It has never been found — and thus, one of the world’s great explorers still lies beneath the waters that once took him around the globe and into the pages of history.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 6, 2025

Wendy Red Star, Searching for Chief Plenty Coups

—This is as guest essay by Wendy Red Star, a visual artist who engages with archival materials in her work. She is an enrolled member of the Apsáalooke (Crow) Nation. It also appears in the May-June issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

In early April of last year, I made a special trip to Washington, D.C., from Portland, Oregon, to research the archives pertaining to my community, the Apsáalooke. I was specifically looking for information on the last chief of the Crow Nation, Chief Plenty Coups. I was not only delighted to find information on him in print, books, newspapers and glass plate negatives, but I also discovered a wealth of material on my tribe.

The information I found is a valuable resource for a solo exhibition I will have at the National Portrait Gallery in D.C. in 2026. This exhibition will focus on Chief Plenty Coups’ life, his travels to D.C., his reverence for the land and his congressional testimonies advocating for the Crow people.It also will highlight his inspiration for creating his own mini-Mount Vernon on the Crow Indian Reservation, land he gifted to be turned into a state park that now holds his estate, burial site, visitor center, house and sacred spring. This vision was deeply influenced by his first trip to Washington, D.C., in 1880 as part of a delegation of Crow chiefs. I can even imagine that on one of his many trips, he might have visited the Library of Congress.

The Library holds an extensive archive related to the Crow tribe, offering invaluable historical insight. Among its collections are early 20th-century photographs of Crow leaders, daily life and regalia, including the works of Edward S. Curtis. Additionally, the American Memory Project provides digitized collections of historical documents, interviews and photographs that offer a deeper understanding of Crow history.

The National Archives and Records Administration records key House documents related to U.S. policies, treaties and governance of the Crow Nation, including the Fort Laramie treaties of 1851 and 1868, which shaped Crow lands and sovereignty. Historical maps detail the evolution of Crow territory before and after U.S. expansion, illustrating land cessions and boundary changes.

Furthermore, oral histories and folklore preserve the voices of Crow elders and veterans, capturing language, traditions and pivotal historical events. The Chronicling America collection includes digitized newspapers covering Crow history, featuring articles on Chief Plenty Coups and the Crow people’s contributions to the U.S. military.

This vast repository of knowledge at the Library is not only a treasure trove for historians and researchers but also for tribal members seeking to reconnect with their heritage and understand the legacies of their leaders.

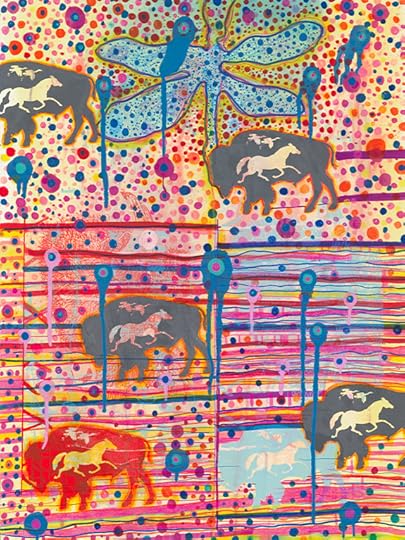

As I explored these archives, I felt a deep connection to my community, even while far from the Crow Reservation. This connection was further strengthened by the knowledge that several of my own artworks are now part of the Library’s collections. These include lithograph prints created at Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts, as well as photographic prints from my Apsáalooke Feminist series.

Knowing that my work is housed within an institution that also holds so much of my people’s history reinforces the importance of artistic and archival preservation in shaping historical narratives. The Library stands as an essential resource for understanding not just the past but also the ongoing contributions of the Apsáalooke people.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

June 2, 2025

Richard Morris Hunt, Star Architect of the Gilded Age

The iconic American architect of the Gilded Age, Richard Morris Hunt, created so much of the nation’s high-brow cultural idea of itself that it’s now hard to imagine the country without it.

He designed estates for the fabulously wealthy, houses that still have their own names — Biltmore, The Breakers, Marble House. In New York, he was the architect for the Vanderbilt mansion on Fifth Avenue, the façade and the Great Hall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the pedestal for the Statue of Liberty. In Chicago, he designed the Marshall Field mansion and the administration building for the World’s Columbian Exhibition.

Hunt and his wife Catharine, spent six decades assembling a collection that eventually included more than 15,000 items — books, papers, drawings, photographs, scrapbooks. That collection, now preserved at the Library, was always intended to be a national resource.

{mediaObjectId:'3596E588D29D2A74E0635D0C938C048F',playerSize:'mediumWide'}“He collects all this and puts it together because he wants to build this museum,” says Sam Watters, author of “The Gilded Life of Richard Morris Hunt,” in a new Library video. “You have this intact collection that’s intended to educate people … that’s what makes it so rare. His collection was conceived to become a permanent public educational force, and that’s what’s at the Library of Congress today.”

Watters’ book on Hunt was published with the Library last year, and the Library’s collections are being used this summer and fall in an exhibit at Rosecliff, one of the mansions of the era in Newport, Rhode Island, where Hunt designed several palatial estates. The exhibit, “Richard Morris Hunt: In a New Light,” for the first time will bring together items from the Library, the National Portrait Gallery and the Preservation Society of Newport County to give visitors an intimate look into his bygone world.

Hunt was born in 1827 into a wealthy and influential Vermont family and was the first American to study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. After he returned home in 1855, he helped work on the expanding U.S. Capitol Building and quickly elevated the nation’s architectural pursuits from the workaday world of the craftsman into professional visionaries of the building trades. He was instrumental in founding the American Institute of Architects and served as its president. He died in 1895.

The Library has digitized about 1,500 images from his papers; there’s also a research guide, outlining his work and history.

“I can’t imagine another collection that’s a better view into the world of the 19th century, where the country needed to go at a time when it was reimagining its future after the difficult years of the Civil War,” says Watters.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 29, 2025

My Job: Chaeli Cantwell, Video Producer

Chaeli Cantwell is a producer in the Multimedia Group.

Tell us about your background.

I grew up in Westminster, a suburban town in central northern Maryland, about 45 minutes from Baltimore City. I graduated from the University of Maryland, College Park, with a bachelor’s degree in French language and literature and then earned another bachelor’s in electronic media and film production from Towson University. During college, I completed two internships at National Geographic, which jump-started my interest in video editing. I began my career at Maryland Public Television, then worked as a video editor in news at WUSA9, a CBS affiliate in Washington, D.C. I later shifted to branded content, joining AARP Studios as an associate producer. I also did freelance work during that time, mostly in the corporate space. When the opportunity to work at the Library of Congress came along, it felt like the perfect fit — blending creativity, video production and my interests in the arts and history.

What does your work involve?

I’m a video producer in the Multimedia Group, where I support live events and produce and edit content that highlights the Library’s vast collections. Prominent examples include the collection of J. Robert Oppenheimer and the Leonard Bernstein Papers. I’ve also worked on videos that are associated with timely events in the news, tributes and celebrations of historical milestones and anniversaries, such as the 100th anniversary of Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.” Along with the four other producers and crew in MMG, I support divisions with video projects by overseeing the full production cycle — from initial ideation and planning to logistics, production, post-production and final delivery. MMG staff members work together from concept to completion on all of these projects, so it’s a very collaborative process — and just so fun to work with such a talented team. From a young age, I’ve always loved history, the arts, film and music, so I feel lucky to create video content that combines so many personal interests. It’s rare in video production to find a role that touches on all of these areas, often at once, so it’s no exaggeration to say this has truly been a dream job.

What are some of your standout projects?

I had the opportunity to produce and edit the latest National Film Registry and National Recording Registry announcement sizzles — short highlight videos. These are team efforts, and the process is always fascinating, especially collaborating with colleagues in MMG, the Office of Communications, the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center and the National Recording Preservation Board. It’s incredible to watch the project take shape and, by the end, feature compelling interviews with iconic musicians, songwriters, actors and filmmakers. Another favorite project from last year involved working with Jennifer “JJ” Harbster of the Science and Business Reading Room and Joshua Levy of the Manuscript Division on two videos about expedition groups that traveled across the world to study solar eclipses in the mid- to late 1800s. We took a close look at what diaries from the expeditions revealed about the journeys and what the expedition teams packed for their travels. In one video, we examined a small leather pocket diary from 1860, owned by renowned astronomer Simon Newcomb, in which he chronicled his five-week, arduous journey through the Canadian wilderness, all to view a solar eclipse. The small team endured a harrowing trek, traveling in birch canoes across large bodies of water and rivers — only to miss the eclipse. That was a fascinating project, and it was remarkable to hear from both Joshua and JJ about all of the solar-eclipse-related items at the Library that reveal powerful stories. When we interview staff members, we get to hear from experts who can detail remarkable moments in history on an exceptionally deep level; it feels like a master class in overlooked niche areas.

What do you enjoy doing outside of work?

I am not athletic in the slightest, and I dread being cold — but, surprisingly, I enjoy skiing. If you’re thinking about trying it, let me encourage you: If I can do it, you definitely can, too!

What is something your coworkers may not know about you?

I am a very open book, so I think they might know everything about me. Maybe they should know I am a terrible baker, so that last cake I brought in was not a fluke or caused by a faulty oven. I am simply a bad baker despite my continued efforts.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 27, 2025

Battle of the Sierra Blanca: The Comanche Map

Soon after the battle, a Comanche warrior put pen to paper to tell the story, in pictures.

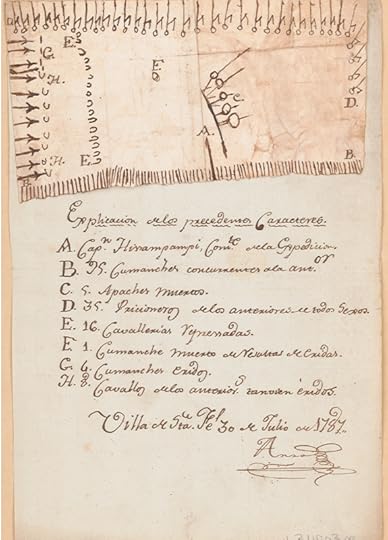

He drew a simple map, ringed with images of warriors and weapons, that chronicles a little-known, 18th-century battle between the Comanches and Apaches in the Spanish frontier province of New Mexico.

The fight, today known as the Battle of Sierra Blanca, was years in the making, and the map is now preserved in the Geography and Map Division.

Apache warriors frequently raided Spanish settlements in New Mexico, a constant concern for provincial Gov. Juan Bautista de Anza. Unable to track and defeat the elusive Apache themselves, the Spanish enlisted the help of their Comanche allies — a mortal enemy of the Apaches.

Under chief Hisampampi, the Comanches accomplished what the Spanish couldn’t. They defeated a large Apache party in far West Texas in April 1787. In July, they routed the Apaches in the Sierra Blanca Mountains of southern New Mexico — a favorite Apache staging ground for raids — and drove them in retreat down the Rio Grande Valley.

The full map with an explanatory legend, written later by Spanish officials. Geography and Map Divison.

The full map with an explanatory legend, written later by Spanish officials. Geography and Map Divison.Immediately afterward, one of the Comanches drew a pictorial map that soon was passed to Anza as an official record of the battle. Officials in the capital of Santa Fe attached the map to a larger sheet and added a Spanish-language key explaining the action depicted. Anza then certified the document with a florid signature and the date of the battle: July 30, 1787.

In the map, Hisampampi (denoted by A) leads 95 warriors (B) into the fight. Five Apaches are killed (C) and 35 taken prisoner (D), and 16 horses are captured (E). One Comanche is killed (F), and four are wounded (G). Horseshoe-shaped symbols represent horses. Arrows denote warriors and horses injured in battle; Apache prisoners are shown with their heads down.

The artist drew the map on paper — an early example of ledger art, so named for the books that in later decades became a source of paper for Native American artists. Today, it’s a rare chronicle of Native history, held in the Library’s collections.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 23, 2025

From Decoration Day to Memorial Day

It was Decoration Day at first.

This was in the mid-1860s in the aftermath of the Civil War, Lincoln’s assassination and the contentious start of Reconstruction. The nation fairly reeked of death; the 1861-65 conflict killed at least 620,000 in a nation of roughly 35 million, or about 2 percent of the population.

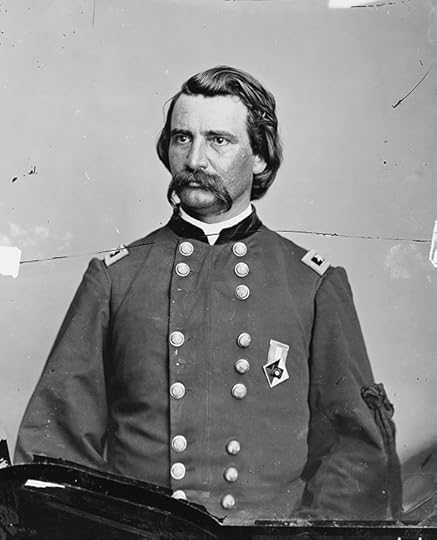

Small organizations around the country on both sides of the conflict had begun to formally mourn the dead even before the war was over. John A. Logan, a member of Congress from southern Illinois before the war and a volunteer who rose to the rank of general during the conflict, wanted to energize his comrades.

On May 5, 1868, as the national commander of the Grand Army of the Republic, the dominant organization of Union veterans, he issued General Orders No. 11, naming May 30 of each year to serve as a remembrance by its members “for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village, and hamlet churchyard in the land.”

Gen. John A. Logan, founder of Decoration Day, U.S. representative and three-time U.S. senator from Illinois. Photographer: Unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

Gen. John A. Logan, founder of Decoration Day, U.S. representative and three-time U.S. senator from Illinois. Photographer: Unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.Decoration Day, as it was dubbed, was observed at Arlington Cemetery 25 days later, with veterans, grieving families, politicians and volunteers placing thousands of flower arrangements on the slim white gravestones.

Given that few communities had escaped the war without a loss, the day quickly served as a national umbrella for the many preexisting local and regional memorial recognitions, in both the Union and the former Confederacy — though Logan clearly delineated the remembrance to honor only Union troops.

“Their soldier lives were the reveille of freedom to a race in chains and their deaths the tattoo of rebellious tyranny in arms,” his order continued. “We should guard their graves with sacred vigilance.”

In 1899, the memorial holiday was firmly established as Decoration Day and observed on May 30, as the writing on the blackboard shows. Photo: Frances Benjamin Johnston. Prints and Photographs Division.

In 1899, the memorial holiday was firmly established as Decoration Day and observed on May 30, as the writing on the blackboard shows. Photo: Frances Benjamin Johnston. Prints and Photographs Division.The Library preserves much of this history, including Logan’s papers, research guides on the G.A.R. and early photographs of celebrations, and the Library’s Congressional Research Service preserves the day’s history and legislative documents.

In 1888, Congress made May 30 a holiday in the District of Columbia, and in 1950 the House and Senate passed a joint resolution calling on the president to “issue a proclamation designating May 30, Memorial Day, as a day for a Nation-wide prayer for peace.”

President Lyndon B. Johnson finally did so in 1968, setting the recognition to begin in 1971 and adjusting the date to be the last Monday in May.

By 1917, when the U.S. had just entered World War I, the holiday was now called Memorial Day and observed veterans from all wars, as this poster for a parade shows. The date was still set at May 30. Artist: Unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

By 1917, when the U.S. had just entered World War I, the holiday was now called Memorial Day and observed veterans from all wars, as this poster for a parade shows. The date was still set at May 30. Artist: Unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.Logan, though not widely remembered today, was a prominent figure in the late 19th century.

He was a highly decorated officer and was wounded in the war. His Illinois constituency sent him to Washington as a member of the House of Representatives and elected him three times to the U.S. Senate. He narrowly missed being elected vice president on the Republican ticket in 1884, when he and presidential nominee James G. Blaine narrowly lost to the Democratic ticket of Grover Cleveland and Thomas A. Hendricks.

Logan died of an illness two years later, at 60, while planning a run for the presidency.

His birthplace in southern Illinois is now a museum; he’s memorialized in the nation’s capital, with Logan Circle in downtown D.C., in the center of which is a statue of Logan astride a horse; and he’s buried across town in a prominent mausoleum in the United States Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home National Cemetery.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 21, 2025

Edward Gorey’s Eerie Vision: The Centennial Edition

Edward Gorey, that bearded patron saint of the sad and whimsical, the strange and witty, was born in 1925 Chicago, deep in the heart of the American continent.

But you’d swear, looking at his comic-but-disturbing illustrated books during the centennial celebrations this year, that the man was born into a dreary British family living in three-room flat in a shabby little village called Puddlington or something.

Happily, the instantly identifiable Gorey universe — built on “The Gashlycrumb Tinies,” “The Unstrung Harp,” his Tony Award-winning costume design for “Dracula,” his animated intro for the long-running PBS show “Mystery!” — has become part of the nation’s background cultural fabric. The films of Tim Burton (“The Corpse Bride”), the one-panel comics of Gary Larson (“The Far Side”) or the Y.A. novels of Daniel Handler (“A Series of Unfortunate Events,” under the pen name of Lemony Snicket ) all bear his influence.

Gorey died of a heart attack 25 years ago at age 75, but his multiplatform work still seems omnipresent. Centennial Gorey commemorations range from a small display at the Library earlier this year to the publication of a lavish new compendium of his work, “E Is for Edward,” coming this fall, and dozens more events across the country.

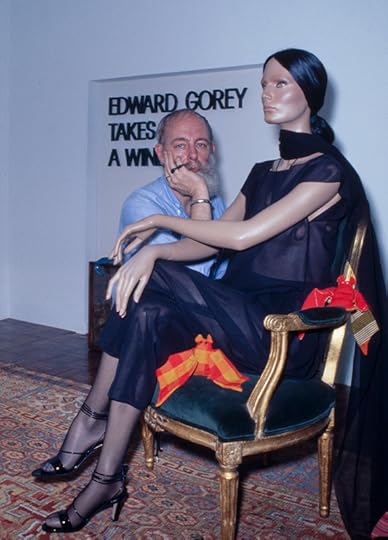

Edward Gorey and a mannequin that he was installing in the window display of the Henri Bendel store in New York. 1978. Photo: Bernard Gotfryd. Prints and Photographs Division.

Edward Gorey and a mannequin that he was installing in the window display of the Henri Bendel store in New York. 1978. Photo: Bernard Gotfryd. Prints and Photographs Division. “Enchanted at first sight,” writes Glen Emil, the collector who in 2015 donated more than 800 Gorey items to form the core of the Library’s holdings, describing his first reaction to seeing Gorey’s work.

For the unfamiliar, Gorey created a pen-and-ink, genteel, British-looking landscape in which bad things happened to small children, people had oddly shaped heads, nameless animals flapped about and a vague air of menace hung about the tea room. The sun rarely shone. He created the covers for hundreds of books, wrote and illustrated more than 100 of his own short works and illustrated posters and magazine articles by the score.

As his charitable trust puts it, his was a “vaguely Edwardian world of patriarchs in ankle-length overcoats, mustachioed men in padded dressing gowns, wantons with nodding plumes, uniformed housemaids, and children in sailor suits and pinafores.”

In almost all of Gorey’s illustrations, everything has just happened or is just about to. You have to fill in something to complete the action, plus add the emotion. The latter isn’t entirely clear because the scenario is kind of amusing and kind of disturbing at the same time. One’s mileage certainly varied, which was the intent.

Emil, who came across Gorey’s work at 18, built a website to showcase Gorey’s work in the early 1990s, when there weren’t even guidebooks for how to do that. He eventually donated the lion’s share of his collection because, after moving to D.C. and visiting the Library in “awe and amazement,” he was surprised the nation’s library lacked some of Gorey’s most charming work.

“I thought, ‘I could fix that!’” he wrote.

With the contribution of another 900 or so items in 2020 from another major Gorey collector, the late Edward Bradford, the Library’s collection grew to more than 1,700 items, many of them as delightfully eccentric as the man himself.

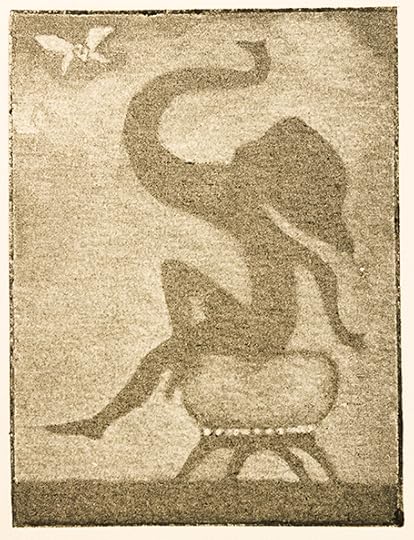

Here, in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, is “Elefantômas,” a limited edition of nine hand-pulled collagraphs. Gorey’s creature is a very slender man with an elephant head. Sort of. The book is wordless, save for the title.

One image from “Elefantômas,” a sequence of nine prints. Artist: Edward Gorey. Photo: Shawn Miller. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

One image from “Elefantômas,” a sequence of nine prints. Artist: Edward Gorey. Photo: Shawn Miller. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.Here is a limited edition of “The Gashlycrumb Tinies” that is … tiny. The smallest matchbook you’ve ever seen. It’s kept in a pouch wrapped in paper tucked inside a bespoke box.

“Gashlycrumb” is styled as a child’s alphabet book, but the cover illustration is a smiling, umbrella-holding skeleton, dressed in black with a flowing scarf, towering over blank-faced tots. Each letter of the alphabet is for a child who is about to die in a most unfortunate way: “A is for Amy who fell down the stairs.” Above this line we see little Amy, ghostly white with huge black eyes, hurtling face-first down a dark, wide set of stairs, arms outstretched.

The next page is “B is for Basil, assaulted by bears,” and there’s the hapless young Basil looking back over his shoulder as two huge bears, not in any particular hurry, walk toward him.

Gorey’s father was a journalist and his grandmother designed greeting cards (he later said she was the source of his artistic talent). The family was comfortable, as young Edward attended the private Francis W. Parker School in Chicago and was friends with Joan Mitchell, the future abstract painter. He took one semester of art classes at the Art Institute of Chicago, served in World War II and got a degree in French Literature from Harvard, where he was roommates with the poet Frank O’Hara.

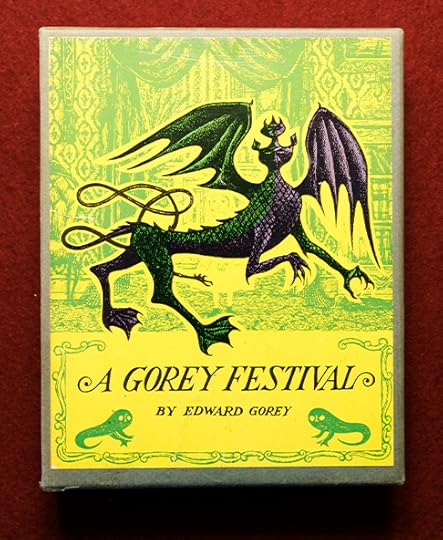

“A Gorey Festival,” one of more than 1,700 items in the Library’s Gorey collection. Photo: Shawn Miller.

“A Gorey Festival,” one of more than 1,700 items in the Library’s Gorey collection. Photo: Shawn Miller.It was there that he found his signature look — long overcoats (in fur, for years), heavy jewelry, a magnificent beard and what were then called “tennis shoes.”

He worked in theater and was a huge fan of George Balanchine’s work at the New York City Ballet. He began illustrating books for Doubleday and eventually began to publish his own stuff, often working with the Gotham Book Mart in New York.

He never married, was outgoing, charming, and eventually bought an 18th-century sea captain’s house on Cape Cod, where he lived with several cats. He described his little books as “Victorian novels all scrunched up.”

Here’s another special edition of “The Curious Sofa,” with the cover made of plush red velvet, looking like it was snipped from an Edwardian sofa. The picture book is mildly sexually suggestive, concerning events at a weekend retreat of sorts, but there’s no one unclothed or even in a state of undress. It ends when “Sir Egbert” shuts the door to the room with the couch and “started up the machinery inside the sofa” with a lever.

The last page is almost blank, except for a small bunch of grapes that Alice, the main character, has dropped, with a tiny portion of the couch visible at the edge of the frame. The caption: “When Alice saw what was about to happen, she began to scream uncontrollably.”

We can only imagine what Gorey would have drawn for his own “Happy 100th Birthday!” card, but it would likely have involved something most regrettably unfortunate for birthday party guests.

A (very) tiny edition of Gorey’s “Q.R.V.” Book printer, Darrell Hyder; bookbinder, Barbara Blumenthal. Photo: Shawn Miller. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

A (very) tiny edition of Gorey’s “Q.R.V.” Book printer, Darrell Hyder; bookbinder, Barbara Blumenthal. Photo: Shawn Miller. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 19, 2025

A Pearl-Studded Book of Psalms, from the 17th Century

Equal parts devotional item and chic accessory, small, ornate prayer books — like the 3-inch-tall Book of Psalms held in the Library’s Lessing J. Rosenwald collection in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division — were a common way to showcase both great wealth and piety in this era of European society. An aristocratic lady might have carried the book with her to church or, like a piece of prized jewelry, brought it out for special occasions.

This customized 1641 Book of Psalms is a marvel not only for its diminutive size, but also for its remarkable condition and lavish decoration. At more than 380 years old, its golden threads remain unfrayed, and its intricate swirls of tiny seed pearls — hundreds of them — appear almost perfectly intact.

The stitching and pearls in this volume have held up for more than 380 years. Photo: Shawn Miller. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

The stitching and pearls in this volume have held up for more than 380 years. Photo: Shawn Miller. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.There’s a colorful coat of arms on both front and back, featuring a floral wreath and the figure of a man above it, brandishing a leaf or tree branch. This coat of arms likely belonged to the family who commissioned the embroidery from a professional needleworker.

There also are little birds in each corner, eyes wide and gold beaks open as if they’re singing. Embroidered in an ombré style, their threaded feathers blend and transform from orange to yellow, blue to green.

The biblical Book of Psalms itself is an ideal choice for a prayer book accessory. A collection of hymns and other songs of praise, Psalms’ poetic structure is perfect for private worship and reflection.

Written in the metered rhyming style favored in England at the time, it would have made for easy reading. Thumb over to the index in the back and find a short prayer for just about any mood or divine theme: wisdom, mercy, hope, trouble. Who said religious devotion couldn’t be convenient and stylish?

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 15, 2025

Native American (Artistic) Visions

-This article also appears in the May-June issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

When Zig Jackson was a broke college kid in the 1970s, he found himself wandering the country with his beloved camera, taking pictures that nobody wanted of people who had been shoved to the edges of the American landscape.

He was born and raised on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in North Dakota, the seventh of 10 children. His name there was Rising Buffalo, and he was an enrolled member of the Three Affiliated Tribes — Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara.

He endured brutal treatment at one boarding school for Native Americans or another, coming out of the experience with not much other than an artistic vision and vague plans for a better life. He wanted to show Native Americans as they were, with an eye that was as humorous as it was empathetic.

“Bob and Mary Apachito, Diné, Alamo, New Mexico,” 2019. Photo: Zig Jackson. Prints and Photographs Division.

“Bob and Mary Apachito, Diné, Alamo, New Mexico,” 2019. Photo: Zig Jackson. Prints and Photographs Division.“I was just a lonely kid driving in my VW bus, driving to reservations to take my pictures,” he says now. “I didn’t have any idea anyone would want them.”

Time, talent and perseverance paid off. In 2005, by then a well-established art photographer, he donated — at the Library’s request — 12 large silver gelatin prints of his work, becoming the first contemporary Native American photographer to be actively collected by the Library.

Jaune Quick-toSee Smith, who passed away earlier this year, in 1998 had become the first modern visual artist to be collected by the Library. These acquisitions formed a watershed moment.

The Library already had some 18,000 images of Native Americans — including the iconic images taken by Edward Curtis in the early 20th century — but nearly all of those were the work of non-Native artists. Many portray Native Americans in the soft focus, romanticized light of an exotic other — the “vanishing Indian” motif — that manipulated history and isn’t reflective of the modern world.

The Smith and Jackson acquisitions, though, proved to be the start of a two decade-and-counting project to preserve a unique viewpoint on American history and culture — art from the descendants of the continent’s first peoples.

The Library now holds more than 200 prints and photographs by more than 50 contemporary Indigenous printmakers and photographers from the United States, Canada and Latin America.

These artists have won fellowships and awards from the nation’s top rank of artistic supporters, such as the MacArthur Foundation and the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Many have works in the nation’s most prestigious art museums and private collections.

The artists include well-known names such as Wendy Red Star, Jim Yellowhawk, Shelley Niro, Kay WalkingStick and Brian Adams. More than 100 photographs, including 38 more from Jackson, have come in over the past five years.

“Triphammer,” 1989. Artist: Kay Walkingstick. Prints and Photographs Division.

“Triphammer,” 1989. Artist: Kay Walkingstick. Prints and Photographs Division.The project was originally led by Jennifer Brathovde, a reference specialist for Native American images in the Prints and Photographs Division. It now involves staff from multiple divisions, who coordinate their work with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian to build complementary collections.

Thematically, these show concerns about the environment, personal and communal identity, social justice and the passage of daily life in kitchens, living rooms and back porches. These are presented in a blend of modernist, abstract, figurative and traditional styles, often with bright new images colliding with traditional art forms. Taken together, they give the nation a widened viewpoint on American art and history.

“We continue to add new works, most recently by Rick Bartow and Lewis deSoto,” says Katherine Blood, fine prints curator in P&P. “And we’ll keep going.”

The images come with all sorts of backstories that enhance their impact.

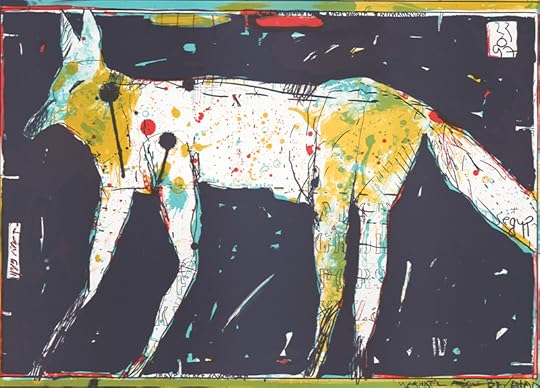

“Segyp Kas’Ket Suit Taup,” 1997. Artist: Rick Bartow. Prints and Photographs Division.

“Segyp Kas’Ket Suit Taup,” 1997. Artist: Rick Bartow. Prints and Photographs Division.Consider Inuit photographer Adams’ story about one of his most well-known photographs — that of fellow Alaskan and Inuit tribal member Marie Rexford, chopping up bowhead whale flesh for a family Thanksgiving Day dinner in Kaktovik, Alaska, in 2015.

It’s at the top of this article and was the cover image of his photo book, “I Am Inuit.” Kaktovik is a village of about 300 people on Barter Island in the Arctic Circle. Even in summer, the average temperature is just above freezing. Muktuk, the blubber and skin of the whale, is a traditional food of the Inuit.

Adams was shooting with medium format film (the negative is 6 by 6 centimeters) and had decided the entire project would be shot with natural light. Given the latitude and that it was late November, he had precious little daylight in which to shoot.

How it happened: Rexford’s family is inside the house behind her, butchering the whale. She’s come outside to place the muktuk on a clear sheet of plastic, which can barely be seen in the dim light. She’s using the stick in her hand to separate it so that it doesn’t all congeal. She’s going to let it freeze, then wrap the chunks in plastic to store for the holiday.

“There was only 40 minutes of daylight at the time,” Adams says. “I had brought a tripod and luckily there was a LED streetlight behind me. I shot it at one-eighth of a second, a really slow shutter speed, with the aperture wide open. I was like, ‘Marie! Hold still!’ I took about three frames, and we went back to what we were doing.”

The image, though, is so striking and well composed that it has found a lasting place in Alaskan culture.

WalkingStick, a member of the Cherokee Nation, in 1995 became the first Native American included in the influential “History of Art” textbook by H.W. Janson. The Library now has five of her works, including a tongue-in-cheek lithograph from her artist’s book, “Talking Leaves.” (The 45-page book is huge; 2 feet wide and 2 feet high, with a wooden cover.)

“You’re an Indian?” 1995. Artist: Kay Walkingstick. Prints and Photographs Division.

“You’re an Indian?” 1995. Artist: Kay Walkingstick. Prints and Photographs Division.In a lithograph from that book, “You’re an Indian?,” made at the Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop, the scrawled text reads, “You’re an Indian? I thought you were a Jewish girl from Queens who changed her name.” On the facing page is a self-portrait in which she’s wearing her favorite hat and a nonplussed expression.

WalkingStick, now 90, said in a recent interview that quote, like all the others in the book, were actual remarks that had been made to her by non-Native peoples (in this case, a good-natured art gallery owner in New York in the cultural hubbub of the late 1960s, when it wasn’t uncommon for artists to try on other names).

“The idea of the book was that people had trouble seeing me as an Indian because I didn’t look like I was an Indian in the movies,” she says. “My mother was Scots-Irish, and I suppose I have her skin. But I made the book out of stupid things that otherwise intelligent people had said to me.”

“Time Keepers.” Artists: John Hitchcock and Emily Arthur. Prints and Photographs Division.

“Time Keepers.” Artists: John Hitchcock and Emily Arthur. Prints and Photographs Division.Shelley Niro, a multimedia artist of Mohawk descent born in New York, has always drawn inspiration from the region’s geography and her place in it. “Knowing the Iroquois people lived in New York state, it tugs at my heart,” she said. “It’s not sentimental or nostalgic, it’s something else. … It’s memory. My father would talk about what his grandmother would talk about, and that’s four generations back. So, whatever he told me about that territory really stuck with me. I just feel that part of that landscape is mine.”

Meanwhile, Zig Jackson’s most influential work is likely his series of black and white photographs featuring him as a Native American in an elaborate headdress, confronting lost lands and history, often with him in front of a “Zig’s Reservation” road sign. In the near distance of one photograph, giving the image an ironic twist, are modern American features such as a power plant, a city skyline or just vast open land.

Now 68, he’s retired from teaching and lives in Savannah, Georgia. But the days of taking those photos, of rambling across the country from reservation to reservation, left him with lifelong friends. Most of their shared memories are positive, he says. Others, like the beatings and abuse they endured in boarding schools, are not.

“I keep in contact with all of them,” he says. “We tell each other we love each other to this day.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

May 13, 2025

“The Tale of Genji:” 1,000 Years of Romance

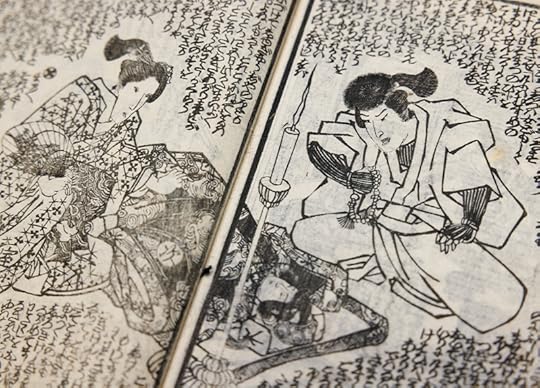

“The Tale of Genji,” one of the foundational works of Japanese literature, was written 1,000 years ago and is more than 1,000 pages long. Penned over the course of a decade or so by Murasaki Shikibu, it is widely considered the world’s first novel. It’s also a landmark of women’s world literature.

The Library has many iterations of “Genji” from down the centuries — full copies, in Japanese and in translations, plus summaries, satires and what you might call graphic novel versions from 17th century. Like the endless reinventions of Western classics, from “The Iliad” to “Romeo and Juliet,” “Genji” holds a central place in Japanese culture, with new works adding to that heft as time goes by.

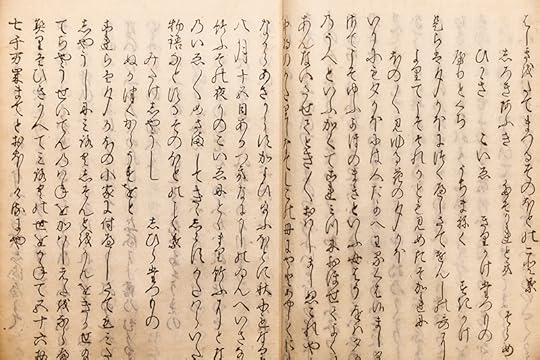

The Library recently added to its impressive “Genji” collections with a beautiful edition of Genji kokagami, or “A Little Mirror of the Tale of Genji,” set in wooden moveable type, from around 1625. It’s a summary of the original with excerpts and explanations, filling three slender notebook-size volumes with thin pages and delicate type. The typeface is so finely wrought that it appears at first glance to be calligraphy.

This truncated edition was extremely popular in its day, as it was important in Japanese society to be on a conversational basis about “the shining prince,” as the titular Genji was known, even if reading the entire opus was not pragmatic. Call it the shorthand for the smart set.

“It made the book much more accessible to many more people,” said Jesse Drian, Japanese reference librarian in the Asian Division, where the books are held.

A page from the Library’s recently acquired 1625 edition of Genji kokagami, or “A Little Mirror of the Tale of Genji.” Asian Division.

A page from the Library’s recently acquired 1625 edition of Genji kokagami, or “A Little Mirror of the Tale of Genji.” Asian Division.But “Genji” is challenging on several levels — its length, archaic language, confusing naming conventions (almost everyone is referred to by their titles, not their actual names), huge cast and a very slow pace that follows characters for decades. Genji dies two-thirds of the way through … and there’s still more than 300 pages to go.

Given all this, it wasn’t translated into English until the late 19th century. When Virginia Woolf read Arthur Waley’s landmark 1925 translation, she was mesmerized.

“All comparisons between Murasaki and the great Western writers serve but to bring out her perfection and their force,” she wrote in a review for Vogue magazine. “… But it is a beautiful world; the quiet lady with all her breeding, her insight and her fun, is a perfect artist … life expressed itself chiefly in the intricacies of behaviour, in what men said and what women did not quite say.”

The scholar Royall Tyler published a highly regarded translation into English in 2001, replete with explanations, footnotes, character lists and helpful drawings and illustrations. He was exhausted by the effort.

“After eight and a half years spent translating, pondering, and discussing it, I still cannot imagine how she created it,” he wrote in Harvard Magazine that same year.

So what’s all the fuss?

An illustrated edition of “Genji,” with words and sketchings filling the pages. Photo: Shawn Miller. Asian Division.

An illustrated edition of “Genji,” with words and sketchings filling the pages. Photo: Shawn Miller. Asian Division.Like most ancient epics, it’s complicated.

“Genji” is a poetic, delicately wrought story about the life and loves of the dashing, sophisticated Genji in Heian period Japan, around 1000. He’s courtly, refined, educated, generous and handsome, but denied a shot at the throne by his father.

But rather than a tale from a long-ago oral tradition finally set down into print, or the rousing tale of a swashbuckling prince out to claim the throne denied him, it’s an intricate examination of aristocratic manners and romantic relationships in the royal city, with a keenly sensitive eye turned toward nature. It’s often said that the book is more a series of independent stories set around a central character rather than a single narrative.

Shikibu was a lady in waiting amid the aristocracy at court and spent more than a decade writing “Genji,” perhaps composing the elegant chapters one at a time for her patron and others. (Woolf admired a passage in which flowers unfolded themselves “like the lips of people smiling at their own thoughts.”) The most refined art at the time was poetry, and in the book she wrote some 800 short poems in Genji’s voice, exquisitely wrought verses that illustrate the book’s sophistication.

The author knew this world well. The capital at the time was modern-day Kyoto, and Shikibu’s father was a poet and aristocrat in the lower branches of government. It’s fitting that Murasaki Shikibu is a nickname of sorts, following the mores of the period in which women were often referred to by references to their male relatives.

“Shikibu” translates as “Bureau of the Ceremonial,” a position her father had held, and “Murasaki” is a plant that produces lavender dye used in clothing. It is also the name of the book’s heroine. (No one is certain of the author’s actual name, although many of her life details are known.) She kept to that practice in the book. As Tyler notes in the introduction to his translation, women without a title “may have no personal appellation at all in the narration.”

Also, verbs don’t always have a clear object. Even after hundreds of years of scholarship, Tyler notes, “it is still possible to argue that this or that speech or action should be attributed to someone else.”

As you might expect, this gets confusing over the course of 1,000 pages covering decades of time and a cast of a couple hundred characters.

Finally, it was composed in a formal version of the language that passed from common use, making it difficult even for Japanese readers to comprehend. (Think of trying to read a work written in Middle English.)

So began the centuries of summaries, the quotations, the heavily illustrated satires — all from one book bringing a country, and then the world, a little bit closer together. Things are different now, but people? As Shikibu shows us, not so much.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers