Library of Congress's Blog, page 9

December 9, 2024

Lift a Glass to Holiday Drinks Gone By

This is a guest post by J.J. Harbster, head of the Science Reference Section, in which she chooses favorite holiday drinks from the Library’s mixology and culinary collections. It follows up on the equally marvelous piece by her colleague Alison Kelly in which she curated favorite cocktails from the Pre-Prohibition era. As always, drink responsibly and be cautious about imbibing the beverages of our ancestors: Times and tastes were different then!

Baltimore Egg Nogg

Love it or loathe it, eggnog originated in the U.S. and is a long-established winter holiday tradition. This recipe comes from the 1862 “How to Mix Drinks,” the first mixology book published in the U.S, by the “father of American mixology” Jerry Thomas. What makes the Baltimore “egg nogg” distinct from other eggnogs? The use of Madeira wine, a favorite of the Founding Fathers.

The Baltimore Egg Nogg recipe is not for the faint of heart. Science Reference Section.

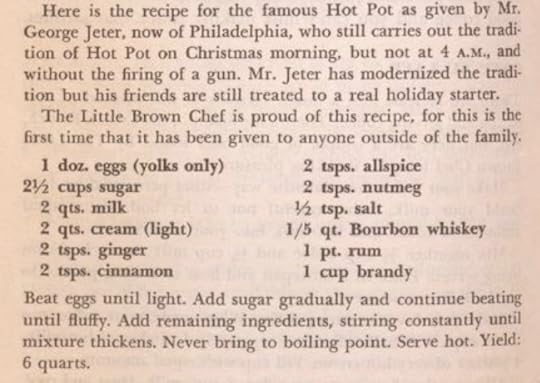

The Baltimore Egg Nogg recipe is not for the faint of heart. Science Reference Section.Jeter’s Hot Pot

The tradition of a Christmas hot pot is “a real starter for a Merry Day and a Merry Christmas,” wrote Freda DeKnight in her 1948 cookbook, “A Date with a Dish.” DeKnight traveled the U.S. collecting recipes from Black chefs, home cooks and caterers. This family recipe for a Hot Pot — a warm melding of spices, sugar, cream and spirits perfect for a cold winter morning or night — has been served on Christmas morning by three generations of Jeters in Caroline County, Virginia, and Philadelphia.

The recipe for Jeter’s Hot Pot makes use of bourbon, rum and brandy. Science Reference Section

The recipe for Jeter’s Hot Pot makes use of bourbon, rum and brandy. Science Reference SectionNorth Pole Cocktail

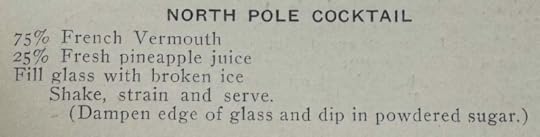

This “fancy drink” looks like a wintry wonderland but tastes like the tropics, and famed New York bartender Jacob Grohusko made his North Pole cocktail easy to concoct. The simple recipe of French vermouth and pineapple in a glass rimmed with powdered sugar was published in Grohusko’s classic work of mixology from 1910, “Jack’s Manual.”

A breeze of the tropics with a wintry twist sets up the North Pole cocktail. Science Reference Section

A breeze of the tropics with a wintry twist sets up the North Pole cocktail. Science Reference SectionFrosted Cocktail

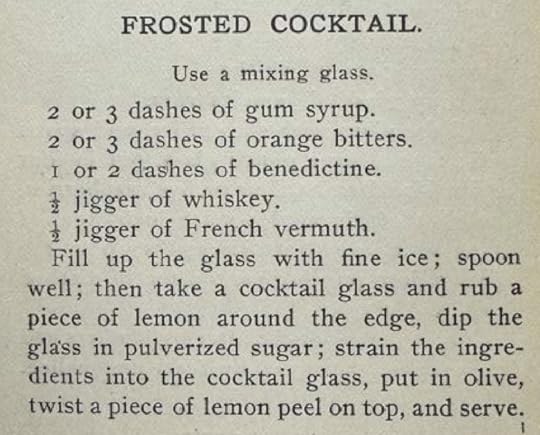

Dashes and jiggers are not names of Santa’s reindeers, they are measurements of ingredients used in this frosted cocktail published in Tim Daly’s 1903 “Daly’s Bartenders’ Encyclopedia.” The cocktail glass rim is “frosted” with pulverized (powdered) sugar and filled with the perfect ratios of spirits, sugars and bitters. The recipe base calls for whiskey (bourbon is recommended). The use of Benedictine, an herbal liqueur, provides additional holiday spice flavors reminiscent of the winter season.

This Frosted Cocktail carries a warm kick for the holiday season. Science Reference Section.

This Frosted Cocktail carries a warm kick for the holiday season. Science Reference Section.Flutemaginely

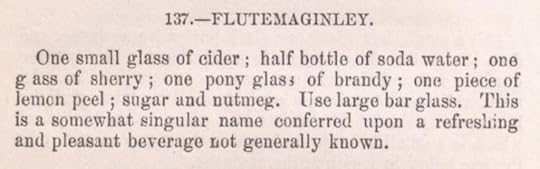

This drink is not only fun to say but also a “refreshing and pleasant beverage not generally known,” wrote Jesse Haney in his 1869 “Steward & Barkeeper’s Manual.” The recipe for this intriguing cider punch calls for the classic holiday spice nutmeg along with the warming properties of brandy. Punches are a popular beverage for holiday occasions and, according to Haney, are “…believe(d) to be the oldest of all made drinks.”

The musical Flutemaginley cocktail dates back to at least 1869. Science Reference Section.

The musical Flutemaginley cocktail dates back to at least 1869. Science Reference Section.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

December 5, 2024

Origins: Mark Twain’s Famous White Suit

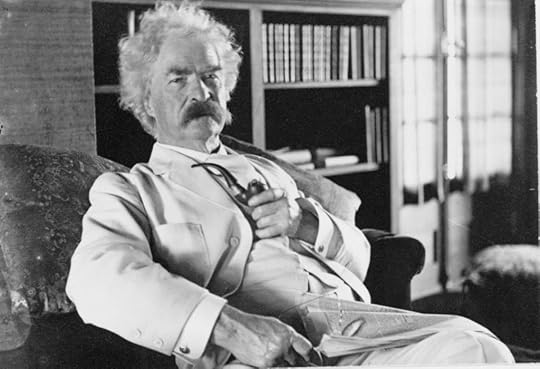

In the winter of 1906, Mark Twain was a tired and grieving man. He was 71. The past dozen years had been brutal.

He had gone bankrupt in the mid-1890s. Then his 24-year-old daughter died from spinal meningitis. Then his beloved wife, Olivia, suffered through years of heart trouble before dying at age 58 in 1904. The couple’s infant son had died decades earlier, and another daughter, Jean, had epilepsy and other health problems.

So, on the frigid D.C. morning of Dec. 7, 1906, when he walked into a copyright hearing at the Library of Congress, one might have expected to see a fading and stooped celebrity, sour faced and grim.

Instead, Twain whipped off his overcoat to reveal a shocking new look: a resplendent white three-piece suit, matching his unruly shock of white hair and bushy moustache and eyebrows. It was a peacock moment, a sardonic splash that delighted the press at the time and would come to define his image for the ages.

“Nothing could have been more dramatic than the gesture with which he flung off his long loose overcoat, and stood forth in white from his feet to the crown of his silvery head,” wrote William Dean Howells, his friend and fellow novelist. “It was a magnificent coup, and he dearly loved a coup.”

“I have reached the age where dark clothes have a depressing effect on me,” Twain quipped to The Washington Post. “I prefer light clothing, colors, like those worn by the ladies at the opera.”

His stunt so completely upstaged the hearing that the Post’s story the next day was headlined simply “Twain’s Fancy Suit.”

“The effect was decidedly startling; it fairly made one shiver to look at him,” the paper wrote.

But there was an important footnote to this triumphant moment. Twain’s career had so tanked during the previous decade that, had it been up to him, he wouldn’t have been at the hearing at all.

His bankruptcy in the wake of the Depression of 1893 (often called the Panic of 1893) was so profound — he claimed in his autobiography that there were 96 creditors he had to repay — that he wanted to give his copyrights back to publishers to help pay them off.

That was stunning. Twain, born Samuel L. Clemens in Missouri, was one of the nation’s most famous and popular personalities. His nation- and globe-trotting adventures had resulted in wildly popular books and speaking tours. He had turned the Mississippi River into a channel of American mythology and created iconic characters such as Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. Given this success, his works had been pirated around the globe, and he was vociferous in the need for copyright protection.

“Among American authors, Samuel L. Clemens was doubtless the most celebrated and certainly the most militant to espouse the cause of international copyright,” wrote Edward Hudon, assistant librarian of the U.S. Supreme Court, in a 1966 American Bar Association Journal article titled “Mark Twain and the Copyright Dilemma.”

And in 1893, this “militant” wanted to give away his copyrights for debt relief?

Henry H. Rogers, Twain’s friend, financial advisor and a principal of Standard Oil, refused to let him do it.

“He insisted they were a great asset,” Twain wrote years later in his autobiography. “I said they were not an asset at all; I couldn’t even give them away. He said, wait — let the panic subside and business revive, and I would see they would be worth more than they ever had been worth before.”

Twain liked the look and posed in a white suit often. Photo: Unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.

Twain liked the look and posed in a white suit often. Photo: Unknown. Prints and Photographs Division.As everyone today knows, Rogers was correct. Twain went on a two-year worldwide speaking tour, paid off his debts and, more than a century later, his reputation is secure in world literature.

“I am grateful to his memory for many a kindness and many a good service he did me,” Twain later wrote of Rogers, “but gratefulest (sic) of all for the saving of my copyrights — a service which saved me and my family from want and assured us permanent comfort and prosperity.”

Twain was at the Dec. 7 hearing to testify in favor of a bill before Congress that would extend copyright of an author’s work from their lifetime plus a maximum of 42 years to a protection of lifetime plus 50 years. It didn’t pass that session and wouldn’t until seven decades later. (Today, it’s lifetime plus 70 years).

But Twain’s suit did win the day and went on to its own afterlife. A few days after the hearing, he posed for photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston in the suit (or one very much like it) and often wore it for public appearances. There is a photograph of he and Rogers standing together; Twain is again wearing the white suit.

After his death in 1910, impersonators began to wear it as an automatic prop (much like Abe Lincoln is associated with a dark suit and stovepipe hat). Actor Hal Holbrook famously donned the suit for his one-man show, “Mark Twain Tonight!” which he performed off and on for six decades, from 1954 until 2017.

Holbrook won both a Tony and Emmy award for this potrayal, and his impersonation of Twain in the suit, along with the famous photographs of him in it, became ingrained in pop culture as the defining image of Mark Twain.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

December 2, 2024

The AIDS Quilt: Digitized at the Library

The Library of Congress has released a groundbreaking online collection of the National AIDS Memorial Quilt Records, making one of the most poignant symbols of the AIDS epidemic in the United States available to a global audience.

As the largest communal art project in the world, the AIDS Memorial Quilt honors the lives of all Americans who have died of AIDS since 1981, when the disease was first identified.

Released to coincide with World AIDS Day (Dec. 1) commemorations, the newly digitized collection offers a unique window into the deeply personal stories behind the 55-ton quilt and its panels. The digitized collection, totaling more than 125,000 items, includes letters, diaries, photographs and other materials documenting the lives of those represented in the Quilt.

The digitized archive is now reunited online with the communal folk art of the quilt panels. Together, these digitized collections will make the Quilt available to everyone. While the Quilt is housed at the National AIDS Memorial in San Francisco, its voluminous records have been entrusted to the American Folklife Center since 2019.

“In the digital age, we have the responsibility and privilege to safeguard this history so that, through every pixel, it can continue to educate, heal, and inspire people for generations to come,” said Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden.

The AIDS Memorial Quilt, created by a group of community volunteers in San Francisco in 1987, has not only been a testament to the lives lost to AIDS but also a powerful tool for advocacy and a stark reminder of the impact of the epidemic on a local, national and global scale.

“Through this project, the power of the collection will now be available to all through the digital platform and can now be reunited with the Quilt panels to which they were originally connected,” said John B. Cunningham, chief executive officer of the National AIDS Memorial. “This collection keeps the stories of the lives cut short alive and allows society to learn from them.”

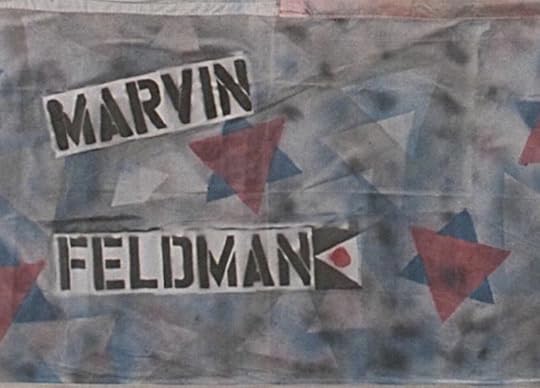

Cleve Jones’ panel in honor of Marvin Feldman.

Cleve Jones’ panel in honor of Marvin Feldman.LGBTQ activist Cleve Jones created the Quilt’s first panel in honor of his friend Marvin Feldman, a 33-year-old actor who died of AIDS in 1986.

“There’s a promise in a quilt. It’s not a shroud or a tombstone,” Jones said. “I don’t want to stop remembering Marvin Feldman and all the other friends of mine who have gone.”

Judy Soons, a mother who lost her sons Sydney and Jim to AIDS, crafted a shared panel to commemorate the closeness of her sons. Soons channeled her grief into supporting others, drawing strength from the community formed through the Quilt.

The Sylvester James panel, showing highlights of his career.

The Sylvester James panel, showing highlights of his career. The late Sylvester James, a gay African American disco star, became a symbol of the fight for LGBTQ equality. Known for his bold and unapologetic embrace of his identity, James rose to international fame with his anthem “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)” serving as a soundtrack for sexual and gender liberation movements. His life and legacy continue to inspire generations, celebrating resilience, self-expression and joy in the face of adversity.

The AIDS Memorial Quilt Records, totaling over 200,000 items, offer an intimate look at the victims’ lives through such artifacts as photos, manuscript letters, diaries, greeting cards, notebooks, tributes, obituaries, epitaphs, pamphlets, fabric swatches, original artwork and so much more. More than half the collection has now been digitized.

While care and treatment can now make HIV a manageable chronic condition, about 8,000 people die with HIV-related illness as a contributing cause of death each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control. More than more than 1.2 million people are living with HIV in the U.S. and there are around 31,800 new infections each year.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

November 29, 2024

Native American Languages, Alive at the Library

This is a guest post by Barbara Bair, a historian in the Manuscript Division. She most recently wrote about Ralph Ellison’s photography work.

Two important collections of Native American heritage have been digitized and placed on the Library’s website, enabling readers and researchers to dig into histories that are not widely known.

The first, featuring portions of the papers of Indian agent and ethnologist Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, focuses on the culture and literature of famed 19th-century Ojibwe poet Jane Johnston Schoolcraft (Bamewawagezhikaquay) and bicultural collaborations and literary contributions of members of her Johnston family of Sault Ste. Marie in Michigan Territory.

The second, some of the papers of naturalist and ethnographer C. Hart Merriam, documents California Indian vocabularies collected from Indigenous language speakers from many different tribal heritages during the first three decades of the 20th century, mostly from California and the adjacent borderlands of Oregon and Nevada.

Both collections provide resources that tribal nations, libraries and cultural centers can use for language revitalization and tribal history documentation, part of the Library’s Native American Collections Working Group’s chief goals. They are housed in the Manuscript Division with other Native American holdings.

It’s fascinating material, taking readers back to a different era. Jane Johnston Schoolcraft’s Ojibwe name translates to “Woman of the Sound That Stars Make Rushing Through the Sky.” Born in 1800, she was the daughter of Susan Johnston (Ozhaguscodaywayquay) and the granddaughter of Waubojeeg, the Ojibwe (Chippewa) leader, warrior and storyteller.

Jane began writing poetry as a girl. Her mother and siblings — especially her sister, Charlotte, and brothers William and George — were instrumental in providing English-Ojibwemowin translations and vocabulary drawn from their multilingual, multicultural networks, including devotional materials and Native American tales and songs.

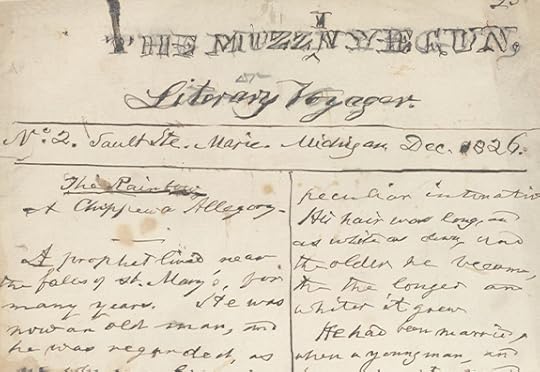

In the winter of 1826–27, family members helped contribute information for a manuscript magazine by Jane and Henry Rowe Schoolcraft called “The Muzzeniegun; or, Literary Voyager,” which also featured poetry by Jane, sometimes under pen names.

The 1826 handwritten volume #2 of “The Muzzeniegun; or, Literary Voyager,” in the Library’s archives. Manuscript Division.

The 1826 handwritten volume #2 of “The Muzzeniegun; or, Literary Voyager,” in the Library’s archives. Manuscript Division. Some of the material gathered, copied or translated by Johnston family members, including draft writings, transcriptions, stories and Anishinaabemowin grammar notes, were collected by Schoolcraft and used in his later publications, including ethnographies and anthologies of Indian tales.

In the last decades of his life, Merriam devoted much of his professional attention to speakers of Indigenous languages in California and the West, gathering information related to linguistic and religious/spiritual matters, material culture and natural history.

The Merriam collection includes over 200 vocabulary word lists documenting information accrued through interviews conducted between about 1902 and 1936.

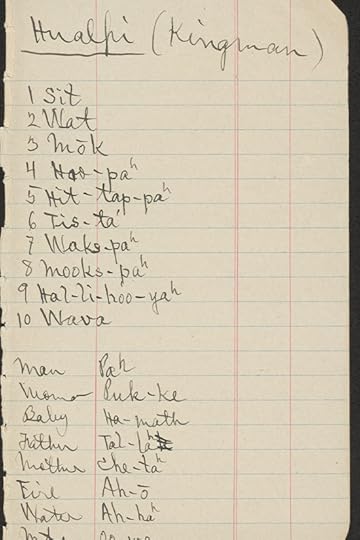

A page from Merriam’s “Indian vocabularies.” Manuscript Division.

A page from Merriam’s “Indian vocabularies.” Manuscript Division. Merriam used phonetic spellings intended to help later readers to pronounce words that were conveyed orally. The names or spellings he used for Native American groups and words were sometimes subjective and may differ from modern renditions or officially recognized terms and tribal designations used today.

In addition to vocabulary lists, the Merriam collection includes over a hundred hand-colored and hand-labeled maps that approximate the location of linguistic groups in sections of California and nearby regions.

Just as he used standardized government-printed field check-lists for his word lists, adding to them by hand, Merriam reused maps of various kinds, including U.S. Forest Service, topographical and geological maps, adding layers of color wash and labeling indicating language-group information. Today, it reveals worlds long lost to new generations.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

November 25, 2024

The Woman Who Helped Put Thanksgiving on the Calendar

This is a guest post by Ryn Cole, who was an intern this summer in the Office of Communications. It appears in slightly different form in the November-December issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

The fourth Thursday in November today means family, food and giving thanks. The national holiday of Thanksgiving, however, did not come quickly or easily. The precedent for a national Thanksgiving holiday can be attributed, in part, to the determination of one woman: Sarah Josepha Hale.

Born in New Hampshire in 1788, she was educated far more than most young women of the era, thanks to parents who believed women should be educated the same as men. She grew to be activist, editor and writer, best known as creator of the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” Her husband, David Hale, an attorney, died young, leaving her with five children. She was socially conservative and did not support womens suffrage, believing that women should confine their influence to home and family. Still, as editor of the popular and influential Godey’s Lady’s Book, a magazine for women, she advocated for an end to slavery, women’s education and for their right to own property. She also very much wanted Thanksgiving, observed mostly in the Northeast, to become a national holiday. After years of advocating for the cause, during the Civil War she finally wrote to President Abraham Lincoln, urging him to proclaim a national day of thanksgiving on the fourth Thursday in November.

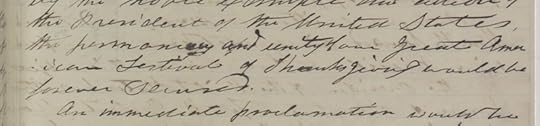

“…the permanency and unity of our great American Festival of Thanksgiving would be forever secured.” An excerpt from Sarah Hale’s letter to Lincoln. Manuscript Division.

“…the permanency and unity of our great American Festival of Thanksgiving would be forever secured.” An excerpt from Sarah Hale’s letter to Lincoln. Manuscript Division.“You may have observed that, for some years past, there has been an increasing interest felt in our land to have the Thanksgiving held on the same day, in all the States,” she wrote Lincoln in September 1863. With Lincoln’s help, Hale hoped “the permanency and unity of our Great American Festival of Thanksgiving would be forever secured.”

Lincoln agreed. On Oct. 3, he issued a proclamation urging his fellow citizens “to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens.”

The divided country was not all on board, as Confederate states didn’t consider themselves subject to Lincoln’s proclamation. Still, Hale’s persistent efforts helped set a precedent of celebrating Thanksgiving in late November. In 1870, congressional legislation officially made Thanksgiving a national holiday and, in 1941, set the day as the fourth Thursday of the month.

More than 160 years after Lincoln’s proclamation, Thanksgiving Day still fills Americans with a sense of community, love and gratitude, thanks in no small part to the determination of Sarah Hale.

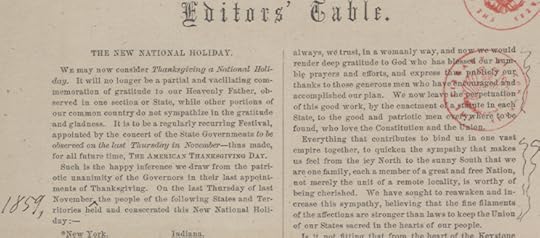

An editors’ column in Godey’s Lady’s Book celebrates Thanksgiving as “The New National Holiday” as Hale’s Thanksgiving campaign was gaining momentum. Manuscripts Division.

An editors’ column in Godey’s Lady’s Book celebrates Thanksgiving as “The New National Holiday” as Hale’s Thanksgiving campaign was gaining momentum. Manuscripts Division.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

November 22, 2024

Historical Holiday Cookbooks … Did We Really Eat This Stuff? (Yes)

This is a guest post by Hannah Ostroff, a public affairs specialist in the Library Collections and Services Group. It appears in slightly different form in the November-December issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

When you sit down for a traditional holiday meal, does your cranberry sauce resemble the fruit or retain the outlines of the can’s ridges? Does the stuffing — or is it called dressing? — go inside the turkey? Who brings the black-eyed peas? Latkes with sour cream or applesauce? Do your family traditions include tamales?

Library collections hold some 40,000 cookbooks, plus thousands of recipe booklets, archival recipes and dietary therapy books, that reflect America’s holiday food traditions — a seasonal smorgasbord of ingredients, techniques, technology and culinary viewpoints.

Cookbooks devoted to the holidays didn’t become popular until after World War II, though festive recipes nevertheless had their place. The first cookbook added to the Library’s collections was at least holiday adjacent. Thomas Jefferson’s copy of “The compleat confectioner; or, The art of candying and preserving in its utmost perfection,” a 1742 volume written by Mary Eales.

Those early cookbooks were smaller and, obviously, lacked the lush photography we associate with modern publications. They didn’t contain specific measurements or instructions, assuming readers possessed a baseline level of culinary knowledge. Imagine a recipe, like one for stewed pears by Hannah Glasse in 1774, simply telling you “when they are enough take them off.”

Cookbooks as we know them today started around the turn of the 20th century.

The books then began including elements expected by the modern home cook, at first explaining methods and measurements at the front — what constitutes a “slow cook,” for example — and later integrating that information into recipes. Instructions were geared to an audience of wives who managed their households and turned to “tried and true” authoritative recipes.

The Library has multiple editions of classics, from Bon Appetit and Betty Crocker, that were mainstays in many homes. “There’s one for every generation,” said Clinton Drake, a reference librarian in the History and Genealogy Section. “People would receive one when they got married and set up a household.”

Drake and J.J. Harbster, a culinary specialist and the head of the Science Section, have pored over stacks and stacks of holiday cookbooks.

Holiday cookbooks reflect the start of convenience foods like cake mix, which became popular in the 1940s and changed Americans’ eating habits. The way to acquire ingredients was changing too, Harbster notes — one could just pop into the store for a can of pumpkin before preparing a pie.

“Back in the day, there were no canned pumpkins, so bakers would simply cut up fresh pumpkins and stew them themselves,” Harbster said.

The detailed cookbooks that started in the late 1800s really took off along with the advent of refrigeration. The means of storing food made a big impact on how cooks planned and dined for the holidays. Virginia Pasley’s 1949 “The Christmas Cookie Book” is organized into chapters based on “cookies that keep,” “cookies that keep a little while” and “cookies that won’t keep.”

Enter the midcentury gelatin era. “The ’50s and ’60s were fabulous,” Harbster said. “They were all about salad, but these salads were not the salads we know.”

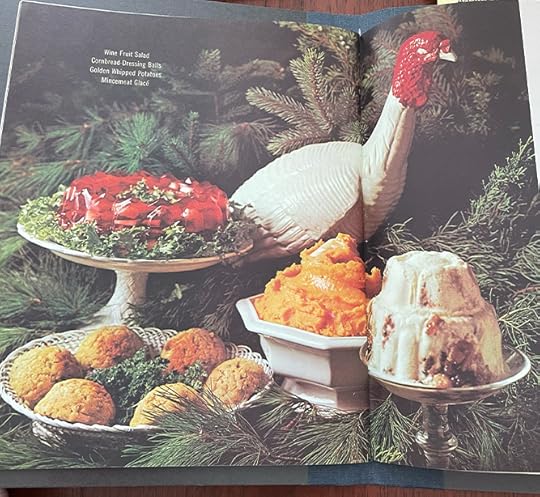

If you were a kid in the 1960s and 1970s, you likely remember “salads” like the red gelatin.

If you were a kid in the 1960s and 1970s, you likely remember “salads” like the red gelatin. “McCall’s Book of Merry Eating,” published in 1965, offers multiple recipes for so-called salads, to be chilled in a mold and served over salad greens. One contains canned corn, a package of frozen peas and carrots and chicken bouillon.

The McCall’s cookbook also includes six (!) fruitcake recipes — plus another for fruitcake ice cream. “[T]o be mellow in time for the holidays,” the inside cover advises, “most of them should be baked shortly after Thanksgiving.” By 1982, “Betty Crocker’s Christmas Cookbook” was offering an “old-fashioned fruitcake” recipe to “evoke Christmas past.”

The rapid pace of technological development in the kitchen shaped innovations in holiday cookbooks. Cooks were eager to try out the promise of futuristic machines, like the microwave and slow cooker.

Barbara Methven describes the holiday season as the busiest time of the year in her 1980s cookbook, “Holiday Microwave Ideas.” Her book provides conventional and microwave directions. She recommends the microwave for a boneless turkey breast, not the entire bird, and while a goose is a no-go in the microwave, she has a recipe for a whole Cornish game hen heated on high for 12 to 17 minutes.

“I just love the optimism of the microwave cookbooks,” Drake said.

The Library’s collections show how regional and global representation have increased in cookbooks by major publishers. In recent decades, the industry has featured authors with diverse backgrounds sharing their own cuisines and traditions, like “Hawai’i’s Holiday Cookbook” by Muriel Miura and Betty Shimabukuro or Gwyneth Doland’s “Tantalizing Tamales.”

Kwanzaa, a holiday established in 1966, brought with it new food traditions. African American culinary historian Jessica B. Harris shares a mix of African diaspora recipes and African American cuisine in her 1995 book, “A Kwanzaa Keepsake.”

Home cooks today have greater access to ingredients than ever.

In the 1940s, Pasley wrote in her cookie book that “since the stuffs that cookies are made of come from the ends of the Seven Seas, you shouldn’t expect to be able to buy them all in one store.” She offered suggestions for where one could obtain more-challenging items. (The most unexpected ingredient in the holiday cookbook collection? The salty star of Prannie Rhatigan’s “Irish Seaweed Christmas Kitchen.”)

More contemporary cookbooks also trace a history of dietary concerns.

The Moosewood Collective, whose New York restaurant dates to the 1970s, focuses on vegetarian cooking. Its 30th-anniversary cookbook, “Moosewood Restaurant Celebrates Festive Meals for Holidays and Special Occasions,” offers menus for Diwali, Ramadan, Chinese New Year and a vegan Thanksgiving. Now, Harbster notes, “plant-based” cookbooks are widespread.

In the collection of the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled, braille holiday cookbooks bring recipes to users. NLS has multiple volumes, including the braille edition of Jeff Smith’s “The Frugal Gourmet Celebrates Christmas.”

No matter the specific recipe or format, there’s often a personal tie to holiday cookbooks.

“Every holiday, it would be tradition to bring out your family’s collection of cookbooks and recipes,” Harbster said.

The holidays help keep food traditions alive, writes Joan Nathan in the 25th anniversary edition of “Joan Nathan’s Jewish Holiday Cookbook.” Nathan names recipes for their authors: “Rose family potato kugel,” “Irene Yockelson’s sweet-and-sour cabbage soup” and “my mother’s brisket.” Harris’ Kwanzaa cookbook has blank pages for family members to record their own recipes and recollections.

Making food is an expression of love — especially if you’re not a year-round cook or baker.

“This is the time when you make all of your special recipes that take a lot of effort,” Drake said. “That’s a theme runs that throughout the collection.”

What’s next in holiday cooking? Given the cyclical nature of trends, Drake predicts those molded salads are due for a comeback.

There’s no accounting for taste.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

November 21, 2024

Scott Joplin & the Magical “Maple Leaf Rag”

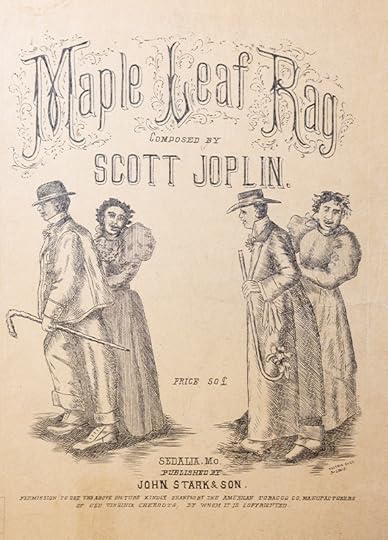

In the final year of the 19th century, a little-known pianist and composer named Scott Joplin and a Missouri music publisher named John Stark sent a small package to the U.S. Copyright Office at the Library.

Tucked inside were two copies of sheet music for a highly syncopated, upbeat piano piece with intense flurries of notes — more than 2,000 in a song that took less than three minutes to perform. It was called “Maple Leaf Rag.”

It blew the doors off everything.

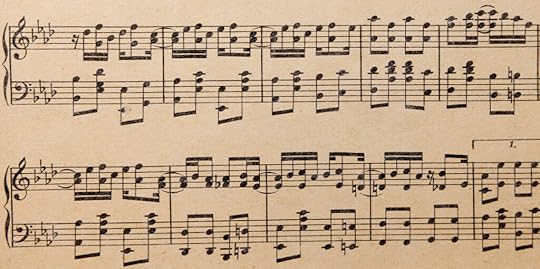

One of the two sheet music copies sent to the Library for copyright registration in 1899. Music Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

One of the two sheet music copies sent to the Library for copyright registration in 1899. Music Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.“Maple” sold 75,000 copies of sheet music in six months, went on to sell millions both as sheet music and in dozens of recordings. It changed the lives of both men and of American popular music. It became the signature piece of ragtime, which also itself lent its name to an era of American life and helped set the foundations for jazz.

“It was a wild success story of fairy-tale proportions,” wrote historian Edward A. Berlin in his definitive “King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era.”

Joplin, who was born 156 years ago this week in northeast Texas (Nov. 24 to be exact), wrote dozens of ragtime pieces, a ballet and two operas and eventually became regarded as one of the nation’s most significant composers and cultural icons.

Decades after his death, he was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for “his contributions to American music” and honored with a U.S. postage stamp. The Library’s National Recording Registry included his work in its inaugural class of 2002 — a group that also included the first recording of George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue,” Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech and Thomas Edison’s landmark 1888 recordings. A St. Louis rowhouse Joplin rented for a year or two after 1900 (the only residence of his known to still exist) was named a National Historic Landmark and is maintained as a Missouri Historic Site.

But when Joplin died in 1917 in New York — of syphilis, at 48, after nearly a decade of illness — he was destitute and largely forgotten. There were only a few photographs of him known to survive. There were no recordings of his voice or of him playing the piano. The only echo of him at the keyboard are heavily edited player piano rolls, the ones preserved in the NRR, and even those were made late in life when his skills were vastly diminished.

“We have very few actual documents or artifacts directly associated with Scott Joplin,” wrote Larry Melton, founder of the Scott Joplin International Ragtime Festival in Sedalia, Missouri, in a Library article for Joplin’s induction into the NRR. “Only a few signatures and annotations bear his handwriting.”

Like the legendary New Orleans jazz trumpet player Buddy Bolden, who also died without a recording, Joplin seemed to fall into the long shadows of American history, a figure composed of equal parts man and myth.

So it’s quite the feeling today to walk into the Music Division and see, resting gently on a table, the two copies of “Maple” that Joplin and Stark had printed and mailed to the Library in 1899.

Now 125 years old, they’re a bit faded, sepia-toned and with the edges a little ragged. The cover features crudely drawn images of two well-dressed black couples out for a night on the town — common to the era, but seen as cartoonish and racist today — taken from a tobacco advertisement. Still, it credits Joplin as composer just below the title and blares his name out in bold type. It sold for 50 cents. Joplin got a penny from every sale. It made him moderately well off for several years. It’s possible the tune was named for the Maple Leaf Club in Sedalia, a black dance hall where he frequently played, but no one is certain.

“No original manuscript for the ‘Maple Leaf Rag’ is known to survive,” says Raymond White, a senior music specialist in the Music Division, “so these two 19th-century copyright deposits of this iconic music are about as close as we can get to Joplin himself.”

A passage from the first edition of “Maple Leaf Rag.” Music Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

A passage from the first edition of “Maple Leaf Rag.” Music Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.When you gently open the cover sheet — a sensation something like stepping back into the ragtime era — you see the cascade of musical notes running up and down and spilling over the staffs, showcasing the complicated, joyful, bouncing piece that so delighted audiences. The prevailing popular music of the time tended to be mawkish and sentimental; this had to land like a lightning bolt. It is so difficult to play that Joplin himself took time to rehearse before playing it in public, and later in life, as his illness took hold, he could scarcely play it at all.

Legendary stride pianist Eubie Blake, a generation younger than Joplin, remembered seeing him perform in Washington, D.C., around 1908 or so.

“He played at a party on Pennsylvania Avenue but he was very ill at the time,” Blake remembered in “Scott Joplin and the Ragtime Era,” by Peter Gammond, the famed British music critic. “He played ‘Maple Leaf Rag’ but a child of five could have played it better. He was dead but he was breathing. I went to see him after but he could hardly speak he was so ill.”

Though much of Joplin’s life is lost to the era and the ambiguities of personal memories, the Library documents much of ragtime’s history and some of his. There are other early copies of “Maple” and his other sheet music; a 1907 copy of The American Musician and Art Journal that has one of only known photos of Joplin (seen at the top of this article); and the oldest known recording of “Maple,” in 1906 by the Marine Corps Band. There also are also interviews with ragtime musicians Max Morath and Joshua Rifkin and then another with Patricia Lamb Conn, whose father, composer Joseph Lamb, knew Joplin well.

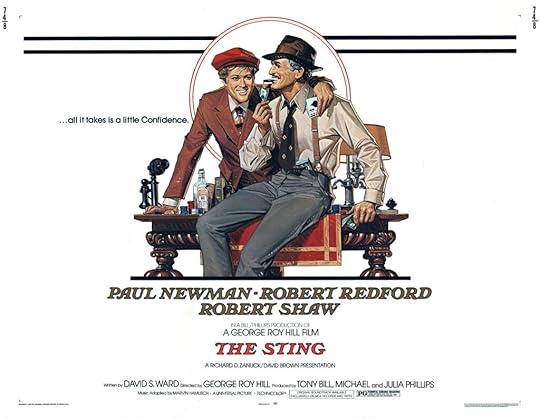

“The Sting,” the 1973 film that renewed interest in Joplin’s music. Internet Movie Stills Database.

“The Sting,” the 1973 film that renewed interest in Joplin’s music. Internet Movie Stills Database.The Library also has the adaptations from Joplin’s work that Marvin Hamlisch turned into the Oscar-winning score for the hit 1973 film “The Sting.” (There is also the Oscar statuette itself.) The soundtrack, composed almost entirely of Joplin tunes, topped the Billboard Hot 100 for five straight weeks in 1974, launching him back into pop culture 57 years after his death. That popularity led to the resurgence and recognition of his career.

Joplin’s prime years were in Missouri and the last decade of his life in New York City, but his music has seemed to capture something timeless in the American imagination.

November 15, 2024

Publishing at the Library, with Aimee Hess

Aimee Hess. Photo:Shawn Miller.

Aimee Hess. Photo:Shawn Miller.–Aimee Hess in the Publishing Office helps produce books highlighting the Library’s collections. This story also appears in the Nov.-Dec. issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Describe your work at the Library.

I am the lead writer-editor in the Publishing Office, where we publish books about the Library and its collections. I oversee our editorial output, such as developing production schedules, ensuring we meet deadlines and reviewing all prepublication text. With just six staff members, we all contribute to get a project from the seed of an idea to something you can buy in the Library of Congress Store, online and in bookstores. This includes developing ideas, writing proposals, archival research, editing text, securing permissions, arranging scanning, working with designers and marketing.

How did you prepare for your position?

I grew up in Westchester County, New York, in the beautiful Hudson Valley. I had many interests: sports, dance, music, theater, nature — and I always had my head in a book. During high school, I studied classical voice in the precollege program at Juilliard and considered going to a conservatory. Instead, I went to Princeton University, where I majored in English with a certificate in African American studies. My education was well-rounded — including a memorable engineering course with David Billington, brother of the former Librarian of Congress — and I really appreciate that I can continue to explore a variety of interests here at the Library.

After graduating, I wanted to work in publishing, so I took an internship at a literary agency and looked for a full-time job. When I accepted the role of editorial assistant in the Publishing Office, I thought I’d stay for a year or two and then move back to New York, but I’ve been here ever since! Since then, I’ve earned a master’s degree in nonfiction writing from Johns Hopkins.

What are some of your standout projects at the Library?

So many come to mind. I’ve had the exciting opportunity to write two books for our Women Who Dare series. For “In Lincoln’s Hand,” the companion book to the 2009 exhibition, I spent time in the Manuscript Division checking transcriptions against Lincoln’s original papers; that was a thrill! I worked with staff in the American Folklife Center to design an interactive e-book, “Michigan-I-O,” that incorporated text, images and audio and video clips.

More recently, my colleague Hannah Freece and I developed the companion book to the 2019 suffrage exhibition, “Shall Not Be Denied,” and we co-wrote “The Joy of Looking,” about the Library’s photograph collections. A particularly fun ongoing project I oversee is our Crime Classics series, where we reprint obscure crime fiction titles, with annotations and other explanatory material.

What have been your favorite experiences at the Library?

My favorite thing about working here is when something amazing happens on an otherwise normal day. For example, one day I attended a meeting where Columbus’ Book of Privileges was sitting out on the table. Another time I tagged along to a display (for filmmaker Ava DuVernay) and got to see the original costume designs for “The Wiz” (and also saw Nancy Pelosi). But more than anything else, my favorite experiences have involved working with so many amazing staff members.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

November 14, 2024

Burt Bacharach: This Guy’s in the Library of Congress

In 1970, Burt Bacharach, whose papers have just been donated to the Library, could sit down at a piano and seem like the coolest cat in the room. Any room.

The once-upon-a-time quiet, skinny Jewish kid from Queens, New York — the one who graduated dear old Forest Hills High School ranked 360th out of 372 kids in his senior class, the one who hated taking piano lessons, the kid his parents called “Happy” — seemed like an L.A. natural by then.

The 42-year-old songwriter and composer was rich and famous, lived in Beverly Hills, owned a stable of racehorses and was married to Angie Dickinson, one of the most glamorous actresses on the planet. His music lived at the top of charts. He scored hit movies. He composed a smash Broadway musical. His television specials did great business. He was admired across the musical spectrum, from the Beatles’ Paul McCartney to Broadway legend Richard Rodgers. His concerts were sellouts, drawing everyone from kids to grandparents.

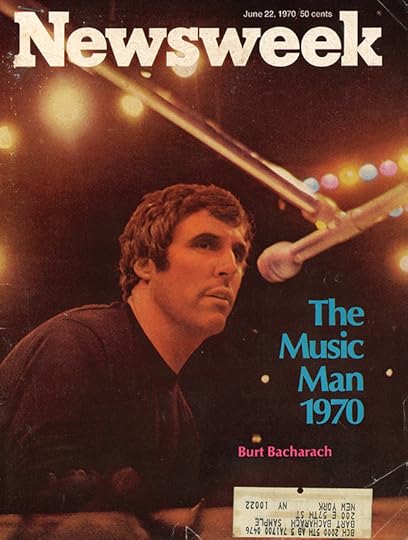

“Burt Bacharach is the prince of popular music,” Newsweek wrote in the summer of 1970, putting him on the cover.

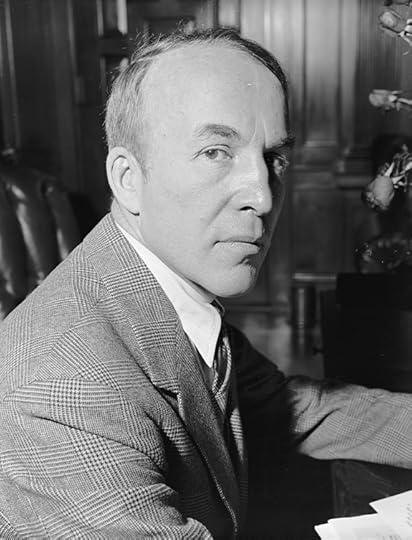

The young Burt Bacharach didn’t like to practice piano. Later, he became obsessive about his craft, going over a song hundreds of times before releasing it. Music Division.

The young Burt Bacharach didn’t like to practice piano. Later, he became obsessive about his craft, going over a song hundreds of times before releasing it. Music Division.More than half a century after that glitzy zenith, Bacharach and his music seem fixed in the nation’s musical canon, for his musical writing, compositions and arrangements amounted to a Rolex watch of musical construction and complexity. They didn’t sound like anything else on the radio. He wrote catchy melodies marked by technically challenging arrangements, shifting time signatures and atypical chords. The songs walked and then ran, paused, swooped and bounced along with odd accentuations, retreated to a single instrument before pounding back in with a full orchestra.

The list of his hits (many written with lyricist partner Hal David) that have endured is stunning. “Walk on By,” “Alfie,” “(There’s) Always Something There to Remind Me,” “Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart,” “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head,” “I Say a Little Prayer,” “(They Long to Be) Close to You,” “Do You Know the Way to San Jose,” “This Guy’s in Love With You” and on and on.

He won three Academy Awards for his work in films; six Grammys for his pop music; two Tonys (for cast members) for that Broadway hit, “Promises, Promises”; a primetime Emmy for a television special; and a Drama Desk Award.

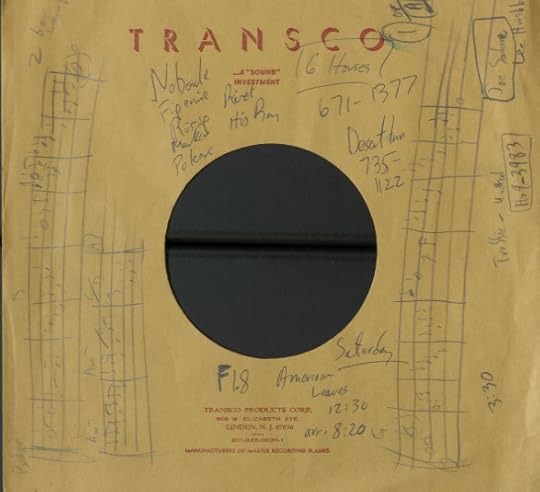

Bacharach sketched an early version of “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head” on this blank record sleeve along with airplane reservations, a hotel phone number and other notes. Music Division.

Bacharach sketched an early version of “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head” on this blank record sleeve along with airplane reservations, a hotel phone number and other notes. Music Division.Bacharach was awarded the Library’s Gershwin Prize for Popular Song (along with David) in 2012 and considered it the pinnacle of his career. “… it was incredible news,” he wrote in his memoir, “Anyone Who Had a Heart.” “This award was for all of my work, and so for me, it was the best of all awards possible.”

He died in 2023, at 94. By then, he was considered one of the greatest writers, composers and arrangers of popular music in the nation’s history.

“Burt Bacharach’s timeless songs are legendary and are championed by artists across genres and generations,” said Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden. “The Library is proud to be entrusted with ensuring his music and legacy will remain accessible for future generations.”

Newsweek, it has to be said, had him pegged way back in 1970. The magazine didn’t compare Bacharach to his contemporaries — the Beatles, Bob Dylan, Smokey Robinson — but to the composers of the American songbook. “He’s the latest in a distinguished line of American popular composers which includes Irving Berlin, George Gershwin, Cole Porter, a line that goes back to Stephen Foster and beyond,” they wrote.

Bacharach’s papers were donated by his wife, Jane Hansen Bacharach, earlier this year. The collection, still being processed, includes 28 boxes full of musical compositions, sketches and scores; nearly 200 photographs; correspondence and other personal papers.

“Burt poured his heart and soul into his music, and we are so proud that the Library will give others the opportunity to visit and enjoy his legacy,” the Bacharach family said in a statement.

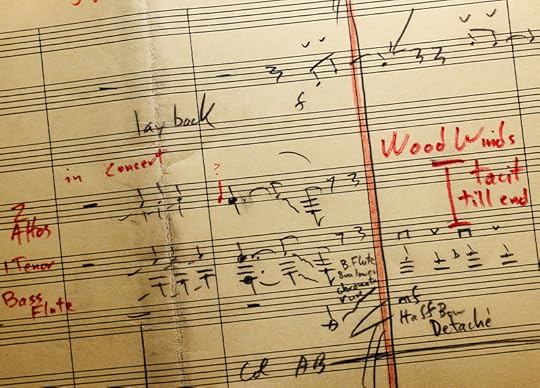

Bacharach’s handwritten score for “The Look of Love” contains detailed notes. Photo: Shawn Miller. Music Division.

Bacharach’s handwritten score for “The Look of Love” contains detailed notes. Photo: Shawn Miller. Music Division.One of the many finds in the collection is Bacharach’s handwritten score for one of his most popular hits, “The Look of Love.” Composed for “Casino Royale,” a spoof James Bond film in 1967 and first recorded by Dusty Springfield, it since has become a seductive jazz standard. That vibe was intentional; one of Bacharach’s notes in the score was for the musicians to play a passage as “languid and sexy.”

His was an inspiring story about innate talent, hard work and perseverance rather than a tale of a born musical prodigy. His mother had great taste in the arts and played piano by ear; his father was in the men’s clothing business before becoming a well-known syndicated newspaper columnist.

Bacharach started piano lessons at 8 but didn’t really come alive musically until hearing jazz great Dizzy Gillespie as a teenager. He trained at the music conservatory at McGill University in Montreal, studied under Darius Milhaud and avant-garde composer Henry Cowell.

His real-life musical education? Touring with the legendary Marlene Dietrich as her accompanist while beginning his songwriting career in the Brill Building in Manhattan.

Then, after spotting eventual muse Dionne Warwick as a backup singer at a recording session and settling in with David as his songwriting partner, he went on a hit-making run for decades.

Bacharach’s personal copy of Newsweek with him on the cover, June 22, 1970.

Bacharach’s personal copy of Newsweek with him on the cover, June 22, 1970.He wrote or co-wrote six No. 1 Billboard pop hits and had dozens in the Top 40. He was enshrined in every relevant hall of fame, made delightful cameos in the three “Austin Powers” movies and saw more than 1,000 artists around the world record his songs. His work was so universal that country star Ronnie Milsap had one of the biggest hits with “Any Day Now,” while rhythm and blues crooner Luther Vandross made “A House is Not a Home” one of his signature pieces.

Linda Moran, president and CEO of the Songwriters Hall of Fame, likes to point out that Bacharach was given their Johnny Mercer Award — a further honor for hall of fame inductees who set “the gold standard.”

“Nothing better describes the magic Bacharach created with every song he wrote,” she said.

Several of his songs have been hits in multiple decades.

Consider “Walk on By,” an early collaboration with David.

Warwick had the first hit with it in 1964. Soul icon Isaac Hayes put it back on the charts in 1969. Several others had minor hits with it in the U.S., the U.K. or Europe over the decades, including the Average White Band, the Stranglers, Melissa Manchester, Sybil and Gabrielle. Then, in 2023, rapper Doja Cat took it to No. 1 in 19 countries by sampling it heavily in “Paint the Town Red,” which has been streamed more than 730 million times on Spotify and another 286 million on YouTube.

Burt Bacharach? It’s almost like he’s still the coolest cat in the room.

Bacharach at the Gershwin Awards in 2012.

Bacharach at the Gershwin Awards in 2012.Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

November 7, 2024

Veterans Day: Remembering World War I

This is a guest post by Cheryl Fox, an archives and history specialist in the Manuscript Division.

In September, the National Park Service unveiled the final element of a new national World War I memorial in Washington, D.C.’s Pershing Park. Titled “A Soldier’s Journey,” the bronze sculpture by Sabin Howard depicts the experience of a single soldier, from enlistment to homecoming, through 38 human figures.

Carved on its opposite side is an excerpt from a poem by former Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish, “The Young Dead Soldiers Do Not Speak,” which concludes with these famous lines, set in all capital letters:

“WHETHER OUR LIVES AND OUR DEATHS WERE FOR PEACE AND A NEW HOPE

OR FOR NOTHING WE CANNOT SAY; IT IS YOU WHO MUST SAY THIS.

THEY SAY: WE LEAVE YOU OUR DEATHS. GIVE THEM THEIR MEANING.

WE WERE YOUNG, THEY SAY. WE HAVE DIED. REMEMBER US.”

MacLeish wrote the poem in 1943 during his tenure as Librarian. Its universal message, calling on citizens to remember and honor fallen soldiers, resonates with MacLeish’s experiences during World Wars I and II.

He interrupted his undergraduate studies at Yale University in 1917 to join the Yale Unit, or Mobile Hospital No. 39, as an ambulance driver. He later joined the U.S. military and commanded an artillery battery at the second Battle of the Marne in France.

By the late 1930s, MacLeish was a well-known cultural figure and multiple prize-winning author closely allied with New Deal initiatives. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt appointed him Librarian in 1939.

Throughout his five-year tenure, MacLeish worked with the Roosevelt administration as a speech writer and spokesman. When asked to contribute to the 1943 War Bond campaign, MacLeish wrote “The Young Dead Soldiers Do Not Speak.”

It was published in newspapers on Sept. 16, 1943, and appeared in the October 1943 issue of the Library of Congress Information Bulletin. An accompanying note reported that MacLeish read it at a general meeting of Library employees on Sept. 10.

After the second World War, Librarian of Congress Luther Evans, who succeeded MacLeish in 1945, asked Congress to provide funds to commemorate Library staff members who died during the war. A white marble plaque with the names of those lost etched in gold resulted. It was dedicated on Dec. 7, 1948, and sits just outside the Librarian’s ceremonial office in the Jefferson Building. A commemorative booklet produced for the dedication included photos and details about fallen staff members — and “The Young Dead Soldiers Do Not Speak.”

Archibald MacLeish in the late 1930s. Photo: Harris & Ewing. Prints and Photographs Division.

Archibald MacLeish in the late 1930s. Photo: Harris & Ewing. Prints and Photographs Division.MacLeish was one of the nation’s most honored and respected poets and intellectuals in the first half of the 20th century. He was awarded three Pulitzer Prizes and an Academy Award, among other high profile honors.

The Library preserves his papers. Many of the public statements, publications and speeches he made during his time as the Librarian appear in the online presentation Freedom’s Fortress: Library of Congress, 1939–1953. The collection includes documents, photographs and printed material from the LC Archives collection and the papers of MacLeish, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter and Manuscript Division chief David C. Mearns.

You can listen to MacLeish reading some of his poems at the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium in 1963 and in 1976 (though “Soldiers” is not included.)

MacLeish is credited with greatly reorganizing the Library and helping turn it into the national institution it is today. In 1942, during World War II, he described its role in sweeping terms: “World events have made the Library of Congress more important now than it has ever been. Today it is, physiologically speaking, the nerve center of our national life.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers